A Fault Confessed Is Half Redressed: The Impact of Deviant Workplace Behavior on Proactive Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Deviant Workplace Behavior (DWB)

2.2. Moral Cognitive Responses to DWB

2.3. Compensatory Response to Perceived Moral Deficit

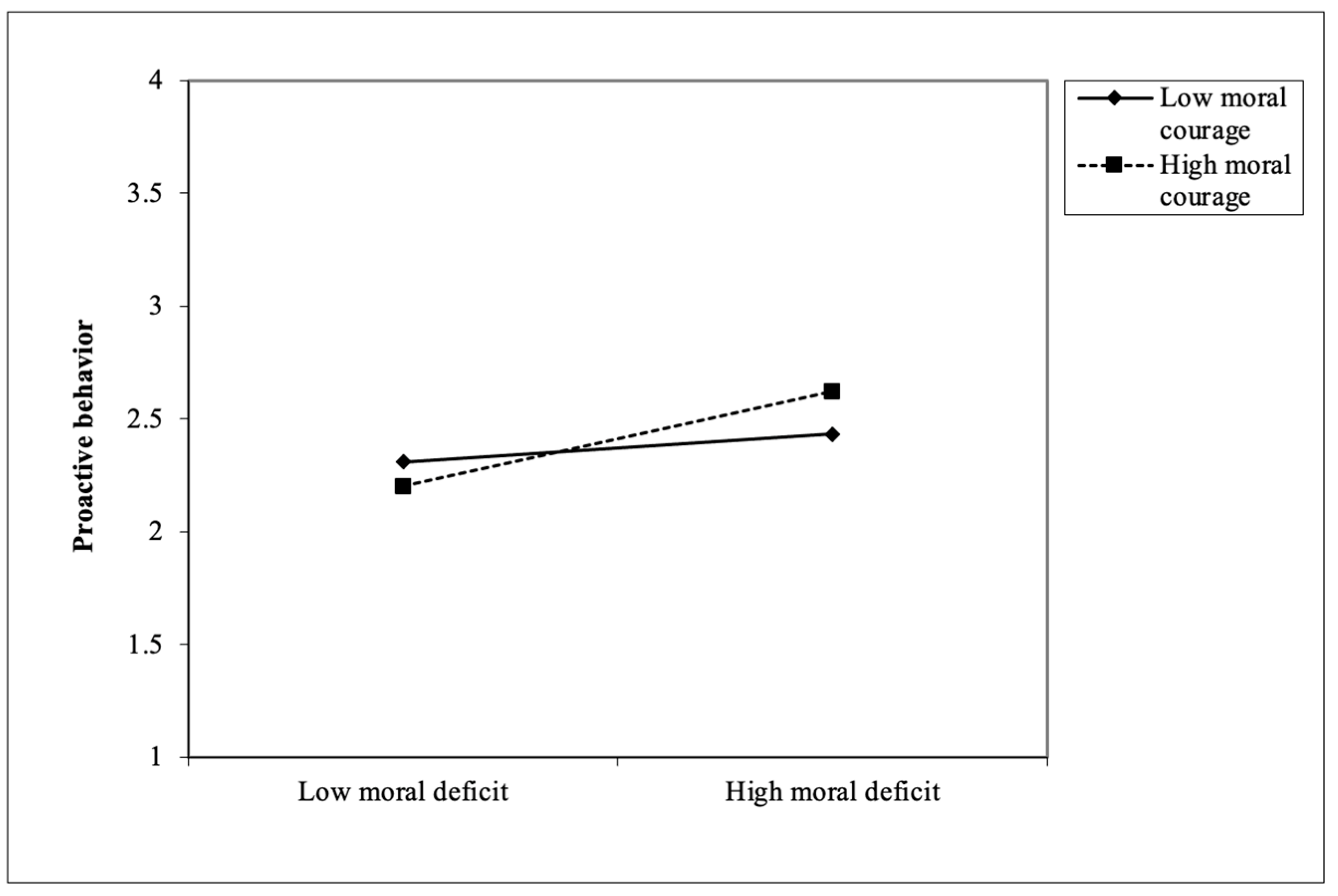

2.4. The Moderating Role of Moral Courage

3. Method

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Design and Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Manipulation Check

3.1.4. Study 1 Results

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Design and Participants

3.2.2. Measures

3.2.3. Study 2 Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, M. Ghufran, Anthony C. Klotz, and Mark C. Bolino. 2021. Can good followers create unethical leaders? How follower citizenship leads to leader moral licensing and unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 106: 1374–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, Faisal Ali H., and Mervat Elsaied. 2022. The mediating effect of moral courage in the relationship between virtuous leadership and moral voice. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 43: 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, Karl, and Americus Reed II. 2002. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 1423–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, Susan J., Ruth Blatt, and Don VandeWalle. 2003. Reflections on the looking glass: A review of research on feedback-seeking behavior in organizations. Journal of Management 29: 773–99. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, Rachel, Shahar Ayal, and Dan Ariely. 2015. Ethical dissonance, justifications, and moral behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology 6: 157–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, Rachel, Shahar Ayal, Francesca Gino, and Dan Ariely. 2012. The pot calling the kettle black: Distancing response to ethical dissonance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 141: 757–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belschak, Frank, and Deanne Den Hartog. 2017. Foci of proactive behaviour. In Proactivity at Work: Making Things Happen in Organizations. Edited by Sharon K. Parker and Uta K. Bindl. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Rebecca J., and Sandra L. Robinson. 2000. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 349–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, Jeremy B., and Herman Aguinis. 2016. A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology 69: 229–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindl, Uta K., and Sharon K. Parker. 2011. Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, LaMarcus R., Liesl K. Becker, and Larissa K. Barber. 2010. Big Five trait predictors of differential counterproductive work behavior dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 537–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chi-Ting, and Brian King. 2018. Shaping the organizational citizenship behavior or workplace deviance: Key determining factors in the hospitality workforce. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 35: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Jin, Haiqing Bai, and Xijuan Yang. 2019. Ethical Leadership and Internal Whistle Blowing: A Mediated Moderation Model. Journal of Business Ethics 155: 115–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryder, Cynthia E., Stephen Springer, and Carey K. Morewedge. 2012. Guilty feelings, targeted actions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38: 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaboyev, Sherzodbek Murodilla Ugli, Yoonjung Baek, and Soyon Paek. 2023. Workplace deviance, emotional state and reparative behaviors: Task visibility as a boundary condition in a mediated moderation model. Baltic Journal of Management 18: 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, James R., and Ethan R. Burris. 2007. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal 50: 869–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, Lindsay Y., and Matthew L. LaPalme. 2019. It’s not personal: A review and theoretical integration of research on vicarious workplace mistreatment. Journal of Management 45: 2322–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, Giovanni, Fabrizio Scrima, and Emma Parry. 2019. The effect of organizational culture on deviant behaviors in the workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 30: 2482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Wan, Ruibo Xie, Binghai Sun, Weijian Li, Duo Wang, and Rui Zhen. 2016. Why does the “sinner” act prosocially? The mediating role of guilt and the moderating role of moral identity in motivating moral cleansing. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschleman, Kevin J., Nathan A. Bowling, and David LaHuis. 2015. The moderating effects of personality on the relationship between change in work stressors and change in counterproductive work behaviours. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 88: 656–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Jigang, Meng Zhang, Xiaolong Wei, Dogan Gursoy, and Xiucai Zhang. 2021. The bright side of work-related deviant behavior for hotel employees themselves: Impacts on recovery level and work engagement. Tourism Management 87: 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Merideth, Dawn Carlson, Emily M. Hunter, and Dwayne Whitten. 2012. A two-study examination of work-family conflict, production deviance and gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior 81: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, Michael, and Doris Fay. 2001. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior 23: 133–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Bryan, Jr., and Laura E. Marler. 2009. Change driven by nature: A meta-analytic review of the proactive personality literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75: 329–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, Joseph P., Mark A. Seabright, Scott J. Reynolds, and Kai Chi Yam. 2015. Counterfactual and factual reflection: The influence of past misdeeds on future immoral behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology 155: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, Majid, Yuan Liao, Sinan Çayköylü, and Masud Chand. 2013. Guilt, shame, and reparative behavior: The effect of psychological proximity. Journal of Business Ethics 114: 311–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, Francesca, and Joshua D. Margolis. 2011. Bringing ethics into focus: How regulatory focus and risk preferences influence (un) ethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 115: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Adam M., and Susan J. Ashford. 2008. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Mark A., Andrew Neal, and Sharon K. Parker. 2007. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal 50: 327–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, Sean T., and Bruce J. Avolio. 2010. Ready or not: How do we accelerate the developmental readiness of leaders? Journal of Organizational Behavior 31: 1181–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, Sean T., Bruce J. Avolio, and Fred O. Walumbwa. 2011. Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Quarterly 21: 555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, Sean T., John M. Schaubroeck, Ann C. Peng, Robert G. Lord, Linda K. Trevino, Steve W. J. Kozlowski, Bruce J. Avolio, Nikolaos Dimotakis, and Joseph Doty. 2013. Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviors: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology 98: 579–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, Remus, Ann Chunyan Peng, Krishna Savani, and Nikolaos Dimotakis. 2013. Guilty and helpful: An emotion-based reparatory model of voluntary work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 98: 1051–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, Kai J., Margarete Boos, and Veronika Brandstätter. 2007. Training Moral Courage: Theory and Practice. Göttingen: Hogrefe Verlag GmbH & Company KG. [Google Scholar]

- Junaedi, Marliana, and Fenika Wulani. 2021. The moderating effect of person–organization fit on the relationship between job stress and deviant behaviors of frontline employees. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 14: 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Howard B. 1975. Self-Attitudes and Deviant Behavior. Santa Monica: Goodyear. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, Anthony C., and Mark C. Bolino. 2013. Citizenship and counterproductive work behavior: A moral licensing view. Academy of Management Review 38: 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischer, Mindy M., Lisa M. Penney, and Emily M. Hunter. 2010. Can counterproductive work behaviors be productive? CWB as emotion-focused coping. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15: 154–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, Jeffrey A., and Linn Van Dyne. 1998. Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 853–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peikai, Kui Yin, Jian Shi, Tom G. Damen, and Toon W. Taris. 2023. Are Bad Leaders Indeed Bad for Employees? A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies Between Destructive Leadership and Employee Outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 191: 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shao-Long, Yuanyuan Huo, and Li-Rong Long. 2017. Chinese traditionality matters: Effects of differentiated empowering leadership on followers’ trust in leaders and work outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 145: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Huiwen, Douglas J. Brown, D. Lance Ferris, Lindie H. Liang, Lisa M. Keeping, and Rachel Morrison. 2014. Abusive supervision and retaliation: A self-control framework. Academy of Management Journal 57: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Jian, Crystal IC Farh, and Jiing-Lih Farh. 2012. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal 55: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Zhenyu, Kai Chi Yam, Hun Whee Lee, Russell E. Johnson, and Pok Man Tang. 2023. Cleansing or Licensing? Corporate Social Responsibility Reconciles the Competing Effects of Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior on Moral Self-Regulation. Journal of Management 50: 1643–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Zhenyu, Kai Chi Yam, Russell E. Johnson, Wu Liu, and Zhaoli Song. 2018. Cleansing my abuse: A reparative response model of perpetrating abusive supervisor behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 103: 1039–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Szu-Han Joanna, Jingjing Ma, and Russell E. Johnson. 2016. When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. Journal of Applied Psychology 101: 815–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, Teng Iat, Kristine M. Kuhn, Arvin Sahaym, Kenneth Butterfield, and Thomas M. Tripp. 2020. From helping hands to harmful acts: When and how employee volunteering promotes workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology 105: 944–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, Scott B., Philip M. Podsakoff, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2011. Challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors and organizational effectiveness: Do challenge-oriented behaviors really have an impact on the organization’s bottom line? Personnel Psychology 64: 559–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Jeremy D., Charn P. McAllister, B. Parker Ellen III, and Jack E. Carson. 2021. A meta-analysis of interpersonal and organizational workplace deviance research. Journal of Management 47: 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, Laurenz L., and Paul E. Spector. 2013. Reciprocal effects of work stressors and counterproductive work behavior: A five-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology 98: 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Qing, Nathan Eva, Alexander Newman, Ingrid Nielsen, and Kendall Herbert. 2020. Ethical leadership and unethical pro-organisational behaviour: The mediating mechanism of reflective moral attentiveness. Applied Psychology 69: 834–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Dale T., and Daniel A. Effron. 2010. Chapter 3—Psychological license: When it is needed and how it functions. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 43: 115–55. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Henry, Dishan Kamdar, David M. Mayer, and Riki Takeuchi. 2008. Me or we? The role of personality and justice as other-centered antecedents to innovative citizenship behaviors within organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Elizabeth Wolfe, and Corey C. Phelps. 1999. Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal 42: 403–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, Elizabeth, and Benoît Monin. 2016. Consistency versus licensing effects of past moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology 67: 363–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisan, Mordecai, and Gaby Horenczyk. 1990. Moral balance: The effect of prior behaviour on decision in moral conflict. British Journal of Social Psychology 29: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Wei, Egan Lua, Zaoli Yang, and Yi Su. 2023. When and How Knowledge Hiding Motivates Perpetrators’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Haesang, Jenny M. Hoobler, Junfeng Wu, Robert C. Liden, Jia Hu, and Morgan S. Wilson. 2019. Abusive supervision and employee deviance: A multifoci justice perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 158: 1113–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Sharon K., and Catherine G. Collins. 2010. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management 36: 633–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Sharon K., Helen M. Williams, and Nick Turner. 2006. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 636–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Sharon K., Uta K. Bindl, and Karoline Strauss. 2010. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management 36: 827–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, Eyal, Laura Brandimarte, Sonam Samat, and Alessandro Acquisti. 2017. Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 70: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, Carlos Ferreira, Maria Francisca Saldanha, Paulo Nuno Lopes, Paulo Renato Lourenço, and Leonor Pais. 2021. Does supervisor’s moral courage to go beyond compliance have a role in the relationships between teamwork quality, team creativity, and team idea implementation? Journal of Business Ethics 168: 677–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip, Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Sandra L., and Rebecca J. Bennett. 1995. A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal 38: 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Sandra L., Wei Wang, and Christian Kiewitz. 2014. Coworkers behaving badly: The impact of coworker deviant behavior upon individual employees. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, Sonya, Rumen Iliev, and Douglas L. Medin. 2009. Sinning saints and saintly sinners: The paradox of moral self-regulation. Psychological Science 20: 523–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Klaus R., Angela Schorr, and Tom Johnstone. 2001. Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, Scott E., J. Michael Crant, and Maria L. Kraimer. 1999. Proactive personality and career success. Journal of Applied Psychology 84: 416–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, Scott E., Maria L. Kraimer, and J. Michael Crant. 2001. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology 54: 845–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerka, Leslie E., Debra R. Comer, and Lindsey N. Godwin. 2014. Positive organizational ethics: Cultivating and sustaining moral performance. Journal of Business Ethics 119: 435–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerka, Leslie E. 2015. Ethics Is a Daily Deal: Choosing to Build Moral Strength as a Practice. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sekerka, Leslie E., Richard P. Bagozzi, and Richard Charnigo. 2009. Facing ethical challenges in the workplace: Conceptualizing and measuring professional moral courage. Journal of Business Ethics 89: 565–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, William E. 2008. Ethical climate in Chinese CPA firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33: 825–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Khuram, Ying Hong, Alan Muller, Marco DeSisto, and Farheen Rizvi. 2023. Correction to: An Investigation of the Relationship Between Ethics-Oriented HRM Systems, Moral Attentiveness, and Deviant Workplace Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, Sabine, and Anita Starzyk. 2015. Perceived prosocial impact, perceived situational constraints, and proactive work behavior: Looking at two distinct affective pathways. Journal of Organizational Behavior 36: 806–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, Christopher J., and Oliver P. John. 2017. Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory-2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. Journal of Research in Personality 68: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Jeffrey P., Daniel S. Whitman, and Chockalingam Viswesvaran. 2010. Employee proactivity in organizations: A comparative meta-analysis of emergent proactive constructs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Jeffery A. 2005. Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 1011–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Meghan A., and Deborah E. Rupp. 2016. The joint effects of justice climate, group moral identity, and corporate social responsibility on the prosocial and deviant behaviors of groups. Journal of Business Ethics 137: 677–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Hung-Yu. 2023. Do you feel like being proactive day? How daily cyberloafing influences creativity and proactive behavior: The moderating roles of work environment. Computers in Human Behavior 138: 107470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R., Lindsey M. Root Luna, and Charlotte VanOyen Witvliet. 2015. Insufficient justification for exclusion prompts compensatory behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology 155: 527–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ying, Shufeng Xiao, and Run Ren. 2022. A moral cleansing process: How and when does unethical pro-organizational behavior increase prohibitive and promotive voice. Journal of Business Ethics 176: 175–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Sarah J., and Laura A. King. 2018. Moral self-regulation, moral identity, and religiosity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 115: 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Colin, and Chen-Bo Zhong. 2015. Moral cleansing. Current Opinion in Psychology 6: 221–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Raenada A., Sara Jansen Perry, Lawrence Alan Witt, and Rodger W. Griffeth. 2015. The exhausted short-timer: Leveraging autonomy to engage in production deviance. Human Relations 68: 1693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Aili, and Wei Wei. 2024. Rationalizing quiet quitting? Deciphering the internal mechanism of front-line hospitality employees’ workplace deviance. International Journal of Hospitality Management 119: 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Xiangfan, Ho Kwong Kwan, Long-Zeng Wu, and Jie Ma. 2018. The effect of workplace negative gossip on employee proactive behavior in China: The moderating role of traditionality. Journal of Business Ethics 148: 801–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Qin, Guangxi Zhang, and Andrew Chan. 2019. Abusive supervision and subordinate proactive behavior: Joint moderating roles of organizational identification and positive affectivity. Journal of Business Ethics 157: 829–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, Kai Chi, Anthony C. Klotz, Wei He, and Scott J. Reynolds. 2017. From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: Examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Academy of Management Journal 60: 373–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, Kai Chi, Ryan Fehr, Fong T. Keng-Highberger, Anthony C. Klotz, and Scott J. Reynolds. 2016. Out of control: A self-control perspective on the link between surface acting and abusive supervision. Journal of Applied Psychology 101: 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Zhenyu, Christopher M. Barnes, and Yongjuan Li. 2018. Bad behavior keeps you up at night: Counterproductive work behaviors and insomnia. Journal of Applied Psychology 103: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Chen-Bo, Gillian Ku, Robert B. Lount, and J. Keith Murnighan. 2010. Compensatory ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 92: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Chen-Bo, Katie Liljenquist, and Daylian M. Cain. 2009. Moral self-regulation: Licensing and compensation. In Psychological Perspectives on Ethical Behavior and Decision Making. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Rui, and Sandra L. Robinson. 2021. What happens to bad actors in organizations? A review of actor-centric outcomes of negative behavior. Journal of Management 47: 1430–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-factor model | 473.04 | 225 | 2.10 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| 3-factor modela | 594.65 | 227 | 2.62 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| 3-factor modelb | 802.91 | 227 | 3.54 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| 2-factor model | 918.49 | 229 | 4.01 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| 1-factor model | 1546.38 | 230 | 6.72 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender a (T1) | 0.52 | 0.50 | |||||||||||

| 2. Age (T1) | 38.34 | 10.82 | –0.22 ** | ||||||||||

| 3. Organizational tenure (T1) | 6.91 | 6.96 | –0.23 ** | 0.48 ** | |||||||||

| 4. Manageiral position b (T1) | 0.41 | 0.49 | –0.18 * | 0.10 | 0.19 ** | ||||||||

| 5. Agreeableness (T2) | 3.74 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.03 | –0.00 | (0.69) | ||||||

| 6. Consciousness (T2) | 3.72 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.20 ** | –0.02 | 0.19 * | (0.81) | |||||

| 7. Proactive personality (T2) | 3.39 | 0.59 | –0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.16 * | 0.33 ** | (0.87) | ||||

| 8. DWB (T1) | 1.91 | 0.66 | –0.07 | –0.23 ** | –0.10 | 0.01 | –0.17 * | –0.36 ** | –0.08 | (0.83) | |||

| 9. Moral deficit (T1) | 2.35 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.21 ** | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.18 * | (0.97) | ||

| 10. Moral courage (T2) | 3.62 | 0.59 | –0.08 | 0.17 * | 0.15 * | 0.12 | 0.23 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.31 ** | –0.17 * | –0.01 | (0.73) | |

| 11. Proactive behavior (T2) | 2.95 | 0.60 | –0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.38 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.12 | (0.90) |

| Variables | Moral Deficit | Proactive Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | |

| Constant | 2.11 ** (0.12) | 2.09 ** (0.27) | 2.87 ** (0.07) | 2.91 ** (0.07) | 2.91 ** (0.07) | 2.92 ** (0.07) |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Gender a | 0.13 (0.16) | 0.17 (0.15) | 0.06 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Organizational tenure | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Managerial position b | 0.42 ** (0.16) | 0.42 ** (0.15) | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.08) |

| Agreeableness | 0.06 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.13) | 0.10 (0.07) | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.07) |

| Consciousness | −0.05 (0.11) | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) |

| Proactive personality | 0.10 (0.13) | 0.08 (0.13) | 0.37 ** (0.07) | 0.36 ** (0.07) | 0.35 ** (0.07) | 0.34 ** (0.07) |

| Independent variable | ||||||

| DWB | 0.34 * (0.12) | 0.30 ** (0.07) | 0.25 ** (0.07) | 0.25 ** (0.07) | 0.28 ** (0.07) | |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Moral deficit | 0.14 ** (0.04) | 0.14 ** (0.04) | 0.14 ** (0.04) | |||

| Moderator | ||||||

| Moral courage | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.07) | ||||

| Interaction | ||||||

| Moral deficit × Moral courage | 0.13 * (0.06) | |||||

| F | 1.47 | 2.37 | 7.28 | 8.29 | 7.43 | 7.23 |

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| ΔR2 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.02 | ||

| Estimate | Bootstrapped SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low moral courage (1 SD below the mean) | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] |

| High moral courage (1 SD above the mean) | 0.07 a | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.09] |

| Index of moderated mediation | 0.04 a | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.10] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Zhao, M. A Fault Confessed Is Half Redressed: The Impact of Deviant Workplace Behavior on Proactive Behavior. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070141

Zhang S, Zhao M. A Fault Confessed Is Half Redressed: The Impact of Deviant Workplace Behavior on Proactive Behavior. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(7):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070141

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Sen, and Mengru Zhao. 2024. "A Fault Confessed Is Half Redressed: The Impact of Deviant Workplace Behavior on Proactive Behavior" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 7: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070141

APA StyleZhang, S., & Zhao, M. (2024). A Fault Confessed Is Half Redressed: The Impact of Deviant Workplace Behavior on Proactive Behavior. Administrative Sciences, 14(7), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070141