Abstract

Fintech has revolutionized the financial sector, providing a new way of providing banking services. Since Fintech can provide the same services as traditional banks but entirely online, it is a competitor. As a result, consumers’ relationships with banking have inevitably changed, and it is therefore relevant to analyze these changes. The main objective of this study is to understand people’s perceptions of Fintech, their level of knowledge about it, and the impact of its emergence on traditional banking. The study sample consisted of 174 participants. A quantitative methodology was used to test the hypotheses formulated. The results show that participants who know about Fintech and perceive it as safe have a greater intention of changing banks. On the other hand, they perceive that supervision and regulation in traditional banks is higher than in Fintech. Among the reasons for becoming a Fintech customer, the most mentioned were lower costs and the fact that they provide greater convenience and ease of use. It will be in Fintech’s interest to continue working with regulators so that the sector makes progress in this area and consumers can recognize greater equality between traditional banks and Fintech in the future.

1. Introduction

The world we live in is constantly changing. Thus, society and people’s way of life have changed significantly over the last few years because of constant globalization, digitalization, and technological developments, inevitably having consequences for the most diverse business sectors that are indispensable to society. The banking sector has been no exception, having adapted to these changes, leading to the emergence of digital banking. This change is still recent, and it represents an alternative for consumers to the traditional banking system that we know so well and that has been present in people’s lives for so many years.

Technological and financial innovation has led to new ways of providing financial services that are more efficient and convenient (Cahete 2020) and create lasting economic value for their users, whether they are financial institutions, investors, or others (Tilman 2020). With the growth in the number of regular smartphone users since 2000, the growth of digital banking has been facilitated, with payments and transactions being made via smartphone, for example (Lee and Shin 2018). Thus, the impact of technology and the internet is notorious in the banking sector, having been noticed by some very important figures, such as Bill Gates, who more than 25 years ago dismissed traditional banks, calling them “dinosaurs” (Mills and McCarthy 2017).

This is how Fintech came to be one of the most crucial innovations in the financial area (Lee and Shin 2018), which provides all the services also provided by traditional banking, such as credits, payments, and transfers, among others (Fernandes 2019), and which has been evolving rapidly, due in part to favorable regulations, information technologies, and the “sharing economy” (Lee and Shin 2018). Fintech represents one of the biggest agents of change in the financial sector worldwide (Moreira-Santos et al. 2022), and its growth reveals a major challenge for traditional banking, which is attentive to its impacts on the banking sector (Fernandes 2019; Jones and Ozcan 2021).

Europe is an interesting market for Fintech companies, with several countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Switzerland at the top of the 2020 Global Innovation Index. It currently represents 27% of the cumulative global valuation of the Fintech industry, receiving 20% of total venture capital investments. Fintech is the largest category of this investment, with a higher percentage than Asia and the United States. Another important factor that makes Europe an interesting market for these companies is the high level of digitization and ease of adaptation to services. Western Europe in particular is an innovative region that quickly adopts new technologies (Paulsen 2024).

In the European context, Portugal is the country that is ageing at the fastest rate, and in 2022, half of its population was over 46.8 years old, the second-highest median age among the 27 state members of the European Union (Faria 2023). Furthermore, according to the latest data from the European Central Bank for 2020, Portugal was in last place in the financial literacy ranking of the 19 eurozone countries (Público 2022). Another study published in 2024 by the Bruegel think tank relating to a survey carried out by the European Commission in 2023 places Portugal as the second worst-ranked country in the European Union in terms of financial literacy (Jornal de Notícias 2024). Given these two factors, Portugal represents an interesting country to study in the field of Fintech, as it stands out negatively regarding issues relevant to the knowledge and use of Fintech.

Therefore, for digital banking to have customers, consumers need to be open to making the transition from traditional to digital. We should also add that the low level of financial literacy in Portugal translates into a certain reluctance when it comes to changing banks. If the system is user-friendly, up-to-date, and allows autonomy, it can make it easier for users to switch banks (Cahete 2020). To open an account with Fintech, the cost aspect will be important, as well as convenience and ease (Fernandes 2019). Finally, according to the literature, it is young people who are more open to change, especially in relation to digital technology, and they have been responsible for the paradigm shift (Cahete 2020; Duarte 2019).

Despite the visible growth of digital banking, some authors consider that traditional banking still has a lot to offer and has the capacity to retain old customers and attract new ones. This is because different business models tend to attract different types of customers (Cahete 2020), and some customers prefer personalized, face-to-face service, something that digital banking cannot offer since it does not provide physical branches (Fernandes 2019).

Most of the studies on Fintech have been performed from a business perspective, such as the studies by Haddad and Hornuf (2019) and Wang et al. (2021). However, this study aims to analyze the evolution of Fintech compared to more traditional banks from a consumer perspective.

The main objective of this study is to understand people’s perceptions of Fintech, their level of knowledge about it, and the impact of its emergence on traditional banking. Thus, it aims to understand at what point people’s knowledge of Fintech is, why they use it or not, and how they perceive its level of security. It also wants to understand people’s perspectives on the supervision and regulation of both digital and traditional banking. As for the impact on traditional banking, it aims to understand for what purposes people use Fintech and to what extent this may influence their use of traditional banking. In addition, it also aims to understand whether the COVID-19 pandemic has been able to impact people’s willingness to use Fintech.

Research questions allow us to identify the question or problem we want to study and to define what the research will seek to discover, explain, and answer. These questions must be clearly defined and will be the focus of the research (Saunders et al. 2019). Considering the gaps found in the literature and the fact that this is an underdeveloped topic, the following descriptive and exploratory research questions were drawn up (Saunders et al. 2019), which we intend to answer:

- What is the level of knowledge and use of Fintech in Portugal?

- What do customers perceive to be the degree of security of Fintech?

- What do customers assess the regulation and supervision of traditional banking and Fintech to be?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Financial Innovation

The last decade has posed enormous challenges for financial institutions, particularly the major financial crisis around the world, responsible for the loss of confidence in the traditional financial sector by its customers (Boot et al. 2021; Fabris 2022) and also generating an increase in operating costs. Thus, this crisis was responsible for financial change and innovation (Fabris 2022). Another driver of change in the economy is the fourth industrial revolution, given the spread of digital technologies (Vardomatskya et al. 2021), the development and spread of the internet, and the digitization and computerization of social and economic life (Gąsiorkiewicz et al. 2020).

However, digital technologies are currently responsible, in a way, for yet another revolution in the banking sector, as traditional financial operators have made efforts to adapt quickly to technological developments so as not to be left behind in the way they deal with their customers (Del Sarto et al. 2023).

Financial innovations, in general, refer to the description of the uninterrupted process of mutations in financial systems, comprising various elements such as markets, financial services and products, financial institutions, financial supervisors, financial infrastructures, and financial regulation. These mutations can be defined in isolation, or, more often, they can interact (Gąsiorkiewicz et al. 2020). Most of these innovations arise in response to the needs of the users of financial systems and the opportunities that arise for their stakeholders, these being financial institutions, regulators, economic agents, and customers (Gąsiorkiewicz et al. 2020).

The financial sector is characterized by rapid growth, where innovation is essential for its growth and development (Martincevic et al. 2022). Thus, the digital transformation has led classic banks to begin to change and become digital banks (Versal et al. 2022), having been the first to adopt digital business to meet the needs of their customers who demanded digital interaction (Martincevic et al. 2022). Today, all banks have some form of digital product to ensure interactive communication and minimal physical contact with their customers (Martincevic et al. 2022), as digital platforms act as a new intermediary between banks and their customers (Boot et al. 2021). This also gave rise to the concept of digital banking, which still needs to be clearly defined, according to Versal et al. (2022).

Thus, the major trend in this area is the intensification of competition between banks and information technology (IT) companies, with the result that banks will become IT companies and IT companies will be even more present in the financial sector through Fintech (Vardomatskya et al. 2021). These developments give rise to a considerable challenge for traditional universal banking, leading to the need for them to change their business model (Boot et al. 2021; Vardomatskya et al. 2021).

2.2. Fintech

The third technological revolution, including digital technology, big data, and cloud computing, has been developing rapidly (Li et al. 2022). The emergence and development of information and financial technology play a significant role in developing the banking sector, especially commercial banks (Li et al. 2022; Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022). A recent example of this impact is the emergence of financial technologies called Fintech (Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022), which originated from the fusion of finance and technology (Li et al. 2022). Its most notable expansion only took place after the 2008 global financial crisis, which is why it is considered by Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė (2022) to be a relatively new area that is growing and has not yet been fully explored.

The significance of Fintech is its large amount of non-financial data, particularly from digital footprints, which can help provide financial services. Given this high volume, data can be analyzed using artificial intelligence and machine learning, creating economies of scale using data, which favors technology companies. Although less studied in the literature, recent innovations in communication are also an advantage and a competitive factor in financial services since they reduce barriers to entry and weaken the traditional role of banks as the first point of connection for financial services (Boot et al. 2021).

Fintech comes from the combination of finance and technology and is beginning to emerge in the 21st century (Martincevic et al. 2022; Ramlall 2018). However, according to Schueffel (2016), the term originated in the early 1990s. Initially, it referred to the background technology of financial institutions, later becoming broader, including financial improvement projects and cryptocurrency, and has become a global word.

The definition of Fintech is different in academic circles (Ramlall 2018), so there are numerous definitions to be found in different studies. Martincevic et al. (2022) consider this as a term to describe new financial technologies that aim to improve and automate the provision and use of financial services. Ramlall (2018) cites the Financial Stability Board, which defines Fintech as financial innovation driven by the continuous evolution of technology.

Fintech companies represent a new technological perspective, which they have brought to traditional banking mainly through discounted financial services. Fintech started with a mere virtual presence and evolved into a more physical presence. However, what defines them is an initial advantage of no-commission credit cards, which are valid internationally (e.g., Revolut) and very attractive to low-cost travelers visiting locations outside their home region, e.g., the Eurozone.

Fintech is based on innovation and technologies that are constantly changing and evolving (Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022). Since they combine technology and finance, Fintech creates new business models, products, and financial services, given the combination of innovation and advanced digital technologies, and is changing the foundations of the financial sector (Martincevic et al. 2022; Vardomatskya et al. 2021). It does not just use digital technologies, as traditional banks do, but it relies entirely on them (Vardomatskya et al. 2021). Thus, Fintech produces new financial products and services based on finance and technology, which are evolving rapidly and transforming the foundations of the financial sector. In this way, Fintech brings digital proximity and can provide flexibility, security, capabilities, and efficiency than the products and services that already exist in the traditional financial sector (Martincevic et al. 2022). In this way, it accelerates financial disintermediation, which leads many customers to abandon commercial banks and turn to Fintech companies (Li et al. 2022).

Through the digitalization and digital transformation of the business model, Fintech offers various tools and innovations that create added value and guarantee a competitive advantage (Boot et al. 2021; Martincevic et al. 2022). The main objective of these entities is to simplify access to financial services, thus making the financial system more efficient (Martincevic et al. 2022). Using technology, they offer financial products that until recently could only be acquired through banks, such as loans, payment services, and financial advice (Del Sarto et al. 2023). Therefore, they affect the ways that customers pay, send money, invest, and take out loans (Anshari et al. 2021).

Fintech is at the center of all debates about the future of banking (Del Sarto et al. 2023). Its revolution has reached the global market and predominantly affects the financial and banking sectors, posing a considerable challenge to the survival of traditional banking (Wang et al. 2021). Despite having different characteristics, Fintech and banks operate in the same financial sector, and competition between the two is increasing in advanced economies and emerging markets (Moro-Visconti et al. 2020). However, unlike large financial institutions, Fintech companies have a small customer base or different stakeholders to satisfy, thus offering customers looking for innovative ways to meet their financial needs convenience and lower costs (Nejad 2022).

Since this is a new practice in the financial sector, it requires new innovative solutions, business processes, regulations, and protection (Martincevic et al. 2022).

2.3. Use of Fintech

Fintech companies can offer their customers access to new, faster, and cheaper financial services via mobile financial applications (Martincevic et al. 2022). Like many services introducing disruptive innovation to an industry, Fintech offers a more attractive, low-cost service and solution to specific needs. As world travel and tourism become more global, a desire to not pay expensive commissions on payments while not wanting to carry local currency “cash” means that financial solutions such as Revolut become very attractive. The issue is, can these new services, such as Revolut, be trusted? Once the trust barrier is overcome and does not have the usual regulatory processes and burdens, Fintech can be more cost-effective. Low-cost solutions are welcomed in a society with a desire and thirst for travel. Additionally, with certain financial zones closing and protecting themselves and adding commissions to commercial transactions, this means that a door is left open to innovative players who can circumvent those costs and barriers. Finally, carrying cash is dangerous (subject to theft), and credit cards are seen as safer; they can be cancelled if lost or stolen. They also have other safety mechanisms and touchless options. The touchless option became attractive after COVID-19, and in certain cultures, people are more concerned or obsessed with hygiene and safety, which is a new and growing reality. Their customers’ demographics, needs, and desires rapidly evolve as Millennials and Generation Z enter the job market. These generations feel less connected to a specific service provider. They are convinced they do not need a traditional financial institution to meet their financial needs (PWC 2020, as cited in Nejad 2022). This change is partly due to their memories of the 2008 financial crisis, with their trust in financial institutions having been negatively affected by their parents’ negative experiences, so they do not want to go through the same difficulties. They are, therefore, looking for alternatives that offer better user experiences and value (Nejad 2022).

Abu Daqar et al. (2020) also investigated Millennials’ and Generation Z’s perceptions of Fintech services, their intention to use them, and their financial behavior, concluding that they have confidence in these services and consider trust, reliability, and ease of use to be the main factors for using a financial service. In turn, Jünger and Mietzner (2020) concluded that adopting new technologies depends on transparency, trust in innovation, and the level of financial education and expertise. Zhou and Madhikeni (2013) identified factors such as trust and customer satisfaction for the continued use of these services. Fernandes (2019) states that consumers decide to open an account with Fintech because of the lower costs, convenience, and ease of opening the account.

Customers, especially younger ones, are looking for easy and fast financial services that are always accessible in any location (Vučinić 2020). Thus, Fintech’s flexibility, convenience, and low cost appeal to younger generations (Nejad 2022). These generations have a greater adoption, acceptance, and use of this type of new technology, are more inclined to accept and use the novelty than the older population, and are also more inclined to do business through financial applications than traditional banks (Martincevic et al. 2022). Thus, we can say that young people are mainly responsible for the transformation of digital financial technology and the paradigm shift in the mindset of banking consumers (Cahete 2020; Duarte 2019).

However, studies show that customers are unwilling to change banks (Jones and Ozcan 2021) and are more willing to do so when they feel familiar with the system, the usability is friendly, and the system works autonomously and is constantly updated (Cahete 2020).

By expanding the range of financial products provided and simplifying their availability, these services are also accessible to residents of small towns, villages, rural settlements, and people with disabilities (Vardomatskya et al. 2021).

Today, academics, researchers, policymakers, and others consider financial literacy to be essential for acquiring financial services (Hasan et al. 2023). These authors conducted a study in which they concluded that knowledge of financial services is a factor that impacts access to financial technology services. Thus, financial knowledge is one of the most relevant factors in promoting access to Fintech. They also found a significant and moderate relationship between financial literacy and financial inclusion, particularly financial literacy, as it affects poor rural consumers, proving that financial literacy significantly impacts the acquisition of financial technology. In addition, individuals with higher education prefer to use financial technology services (Hasan et al. 2023).

Similarly, knowledge about acquiring Fintech services impacts access to them. Since rural consumers are only familiar with a small number of Fintech services, they are limited to only those specific services. Thus, proper financial education would enable rural consumers to obtain financial technology services (Hasan et al. 2023).

Based on the literature above, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 1.

Knowledge of Fintech significantly affects the intention to change banks, with participants who know about Fintech being expected to have a greater intention to change banks than participants who do not know about Fintech.

2.4. Security

New financial technologies, mainly digital banking services, have revolutionized the financial sector and provide customers with convenient and accessible banking services, opportunities, and pleasures. However, the increased use of these services and Fintech also brings new risks, concerns, and challenges regarding consumer protection and security (Gąsiorkiewicz et al. 2020; Gopal et al. 2023). These include cybercrime, data protection and privacy, and financial inclusion (Gąsiorkiewicz et al. 2020). Since Fintech has not changed the function and essence of a financial intermediary, it continues to have traditional financial risks despite making them more hidden. It also includes moral and technical risks relating to internet software and hardware (Li et al. 2022). Competent authorities know that entering Fintech into the provision of services entails risks, raising concerns regarding consumer protection (Eichengreen 2023).

In general, the entry of Fintech into the financial sector has led to greater attention being paid to the security of the banking sector and, consequently, to a more robust regulatory framework to ensure the security of financial systems. Collaboration between these companies and regulators is essential to ensure that technological advances are used to improve financial security rather than degrade it. Thus, the main objective of research into Fintech and banking sector security is to improve the reliability and security of financial services and to protect financial transactions and customers’ personal information, thereby reinforcing the overall strength of the financial sector (Gopal et al. 2023). However, this question of security is a legal issue, and the legislation of each state determines the rules (Peráček 2021). In the view of Hesekova Bojmirova (2022), in addition to each state’s regulations, there should be a horizontal comparison of their regulations in the definition of a transnational approach to the regulation of Fintech.

There are several security risks and challenges associated with digital banking and Fintech. Some of the main ones to consider are cybersecurity, systemic risk, identity theft, insider threats, conduct risks, and third-party risks (Gopal et al. 2023).

Based on the literature mentioned above, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2.

The perceived security of Fintech has a significant effect on the intention to change banks, with participants who perceive Fintech as secure being expected to have a greater intention to change banks than participants who do not perceive Fintech as secure.

2.5. COVID-19

The global coronavirus pandemic in 2020 has shaken the world in a way that has been unprecedented in the recent past. In just a few months, it has affected the entire world, significantly altering the modern world and leading to enormous loss of life, major changes in lifestyle, and devastating consequences for the global economy. The restriction on the movement of people and the difficulties in the movement of goods and capital affected many companies and individuals, leading them to face various challenges that are still present today. The functioning of economic operators was also significantly impaired, leading to an increase in major business risks (Fabris 2022).

These events impacted the digitalization of the banking system, so the pandemic was an accelerator of this process, especially in countries with lower rates in the pre-pandemic period (Versal et al. 2022). Banks were slow to adapt to digital innovation and would have continued to do so. However, COVID-19 changed everything and accelerated the application of innovative technologies in the banking sector. However, digital banks have benefited more from digitalization during the pandemic and have been more sought after by households and individuals compared to traditional banks (Versal et al. 2022). In addition, during the pandemic, many bank branches were closed, forcing customers to resort to remote means to meet their financial needs, so most future consumers may never enter a bank branch, handling all their needs with innovative financial solutions (Nejad 2022).

2.6. Regulation and Supervision

Financial markets are highly regulated, and authorities are aware that the entry of Fintech into service provision raises concerns about market integrity and financial stability and exposes the need to regulate the implementation of these companies, supporting innovation (Vučinić 2020; Martincevic et al. 2022; Eichengreen 2023). Although recognizing the need for regulation is a first step towards developing a response, it is not enough (Eichengreen 2023). Moreover, this interest of regulators, industry participants, and consumers in the financial technologies sector only emerged after 2014 (Galazova and Magomaeva 2019).

The pressure to regulate Fintech has increased as more and more risks have emerged. Firstly, many of the new financial activities did not fit well with existing regulations, i.e., they were unregulated, which gave rise to a regulatory vacuum and, consequently, massive fraud and other illegal activities. Secondly, many consumers needed to prepare to assess the risk of emerging new products, which also facilitated fraudulent activity. Thirdly, significant tech lending became intertwined with the banking system, so regulators feared that banks would be at risk if the risk control of Fintech lending were not as robust as promised. Fourthly, the free flow of data has jeopardized citizens’ privacy, leading to cybersecurity risks (Chorzempa and Huang 2022).

Fintech has transformed the banking sector, and regulators have had to adapt to the new risks and challenges (Gopal et al. 2023). To meet these challenges, regulators must strive to acquire the technological expertise needed to exercise adequate supervision (Eichengreen 2023). New regulations and guidelines have been introduced in various areas, including data protection, cybersecurity, customer identification, and fraud prevention, to ensure the security of financial systems and the protection of customers’ interests. In addition, regulators have increased supervision and monitoring of the banking sector, ensuring that institutions comply with regulations, and they have worked closely with Fintech companies to promote innovation, always ensuring the protection of customers and financial systems. In this way, the regulatory framework for the security of the banking sector has significantly evolved since the emergence of Fintech (Gopal et al. 2023).

The agencies regulating commercial banks should be the same that regulate digital banks, as they have essential expertise, and these banks are close substitutes, which is relevant for assessing competition and market integrity (Eichengreen 2023).

Countries have different approaches to regulating Fintech, as the factors influencing its development can be country specific (Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022; Eichengreen 2023). In the case of the European Union, Ringe and Ruof (2020) consider that the regulatory framework is of little help, given its slow evolution and adaptation. The regulations were drafted before the emergence of Fintech, so the regulatory problems in mind were different. Thus, the rules are both over-inclusive and under-inclusive since many of the categories used are difficult to adapt to Fintech activities. In addition, member states apply the rules in different ways, which results in different rules depending on the country, creating uncertainty for the market and regulators (Ringe and Ruof 2020).

Therefore, it is important for regulators to cooperate internationally to preserve financial stability in this new world of technological and financial innovations (Vučinić 2020). As innovation intensifies, it becomes essential that supervision and regulation are of high quality and that regulators can guide the social debate on the trade-off between innovation and stability, avoiding pressures for unlocked innovation as memories of past financial crises are forgotten. There is also a risk that policymakers will be left behind, protecting outdated business models, not having a structured approach to new entrants, and not being prepared to deal with new technologies (Boot et al. 2021).

Based on the literature above, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 3.

The perception of supervision in Portugal differs significantly between traditional banks and Fintech and is expected to be higher in traditional banks than in Fintech.

Hypothesis 4.

The perception of regulation in Portugal differs significantly between traditional banks and Fintech, with regulation expected to be stronger in traditional banks than in Fintech.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

The methodology followed is quantitative since the technique used for data collection was a questionnaire (Saunders et al. 2019). This was carried out on the Forms UA platform.

The questionnaire initially consisted of a short introduction to the topic, followed by a description of the purpose of the questionnaire and its estimated duration. A call for participation was also made, guaranteeing the anonymity of the responses and compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), with the participants having to confirm that they had read and agreed with the information provided to participate in the survey. The data were collected between April and September 2023.

3.2. Participants

This study’s sample consisted of 174 participants, 78.2% of whom were female and 21.8% male (Table 1). Regarding age, 38.5% of the participants were aged between 18 and 30, 17.2% were between 31 and 40, 25.9% were between 41 and 50, and the remaining 18.4% were aged 51 or over (Table 1). Regarding their educational qualifications, 21.3% had a 12th-grade education or less, 39.7% had a bachelor’s degree, and 39.1% had a master’s degree or higher (Table 1). As for where they lived, 17.8% lived in a village, 12.1% in a town, and the vast majority lived in a city (70.1%) (Table 1). Regarding working or having worked in the banking sector, only 8% of the participants responded positively (Table 1). When asked whether they physically go to the bank, 61.5% answered yes, going to the bank to “ask for information”, “deposits”, “withdraw money”, and “open an account”, followed by “credits” and “investments” and “buy checks and “insurance”. As for the number of times they went to the bank in person, most said they only went once a year or every six months.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

IBM SPSS Statistics 29 was used to analyze the data obtained through the questionnaire. The sample was characterized (analysis and descriptive statistics), and the variables under study were descriptively analyzed by calculating frequencies and percentages.

As for the variables “Reason for being a Fintech client”, “Reason for not being a Fintech client”, and “Evaluation of the degree of supervision and regulation”, the percentage of responses was calculated for each answer point of the questions. For the categorical variables, independence tests were also carried out using the chi-squared test after checking the respective assumptions. To test the hypotheses, as the dependent variables were ordinal, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test (when the independent variable consisted of independent samples) and the Wilcoxon test (when the samples were paired) were carried out.

The significance level, set at 0.05, was used as a threshold for determining the statistical significance of the results. This means that any p-value less than 0.05 indicates a significant result, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis.

3.4. Instrument

The questionnaire comprised two sections, the first dedicated to personal attributes and the second to knowledge about Fintech, with 18 questions. All the questions were closed-ended. The questions in the second section on knowledge of Fintech were drawn up according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Base structure of the questionnaire.

The items relating to the reason for being a Fintech customer, the reason for not being a Fintech customer, switching banks, and the impact of COVID-19 were coded on a Likert rating scale (from 1 “Strongly Disagree” to 5 “Strongly Agree”). The items related to the perception of supervision and regulation were coded on a Likert rating scale (from 1, “Not at all” to 5, “Very much”).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Variables under Study

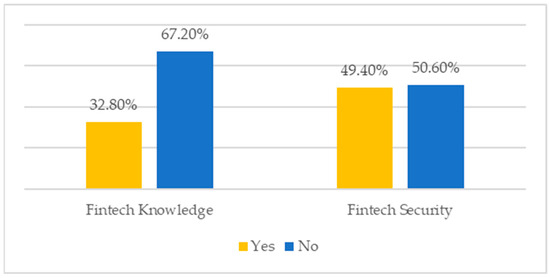

Regarding their knowledge of Fintech, only 32.8% of the participants said they had a good knowledge of it (Figure 1). However, 49.4% said they were safe (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Knowledge and security of Fintech.

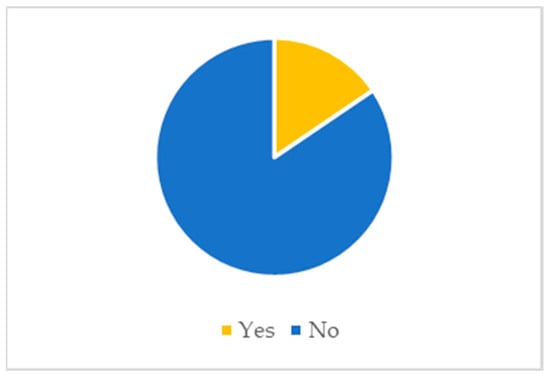

When asked if they were Fintech clients, only 15.5% of the participants said they were clients of a Fintech (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fintech client.

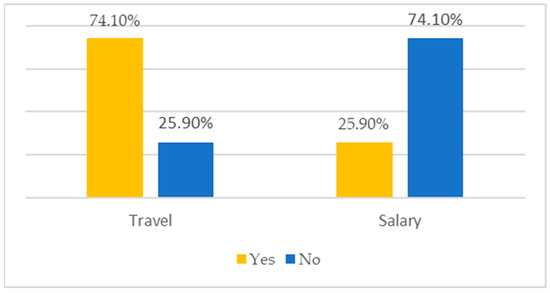

Among the participants who were customers of a Fintech, 74.1% used them when travelling and 25.7% used them to receive their salary (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Using Fintech.

When asked why they were Fintech customers, most of the participants agreed or totally agreed that it was because of the lower costs, which provided greater convenience and ease of use (Table 1). As for the online experience being better than traditional banks, the distribution of the results was different, and the highest percentage of responses was in the middle of the scale (neither agree nor disagree) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reason for being a Fintech client.

Regarding the reasons for not being a client of Fintech, the most significant percentage of the participants agreed or totally agreed that it was due to a lack of awareness of its existence and a preference for face-to-face and personalized service (Table 3). Regarding having little knowledge of the internet, most of the participants disagreed or totally disagreed that this was the reason for not being a client of a Fintech (Table 3). As for the lack of security, the distribution of results was different, with the highest percentage of responses being “neither agree nor disagree” (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reasons for not being a Fintech client.

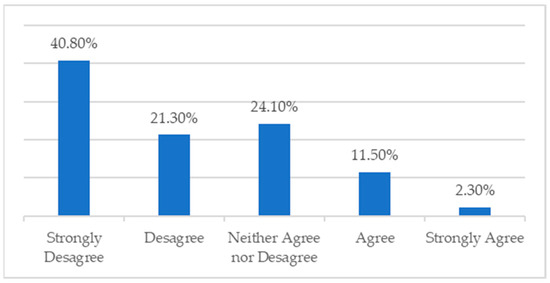

Regarding the possibility of switching from a traditional bank account to a Fintech one, most of the participants said they disagreed or strongly disagreed with making such a switch (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changing from a traditional bank to a Fintech.

Regarding feeling more likely to use a Fintech after the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the participants also said they disagreed or strongly disagreed. However, there was a slight increase in the responses of “agree” and “strongly agree” compared to the previous question (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Switching from a traditional bank to a Fintech post COVID-19.

Regarding the participants’ evaluation of the degree of supervision and regulation of banking, there were many responses in the middle of the scale (neutral) (Table 4). However, in the case of banks, there was also a high number of “moderate” and “very” responses, while for Fintech, the same was valid for the “not at all” and “very little” responses (Table 5).

Table 5.

Evaluation of the degree of supervision and regulation.

4.2. Independence Tests

Several chi-squared tests were carried out to test whether some of the variables were independent of each other.

The results showed that knowledge of Fintech was not independent of the participants’ gender (χ2(1) = 15.44 p < 0.001; V = 0.31). The male participants had a greater knowledge of Fintech than the female participants (Table 6).

Table 6.

Knowledge of Fintech * gender crosstabulation.

Knowledge of Fintech was not independent of the age group to which the participant belonged (χ2(3) = 7.97 p = 0.047; V = 0.21). Participants belonging to the “18 to 30 years” and “51 years and older” age groups have the greatest knowledge of Fintech (Table 7).

Table 7.

Knowledge of Fintech * age group crosstabulation.

Knowledge of Fintech was not independent of whether the participant was working or had worked in the banking sector (χ2(1) = 12.33; p < 0.001; V = 0.29). The participants who worked or had worked in the banking sector had a greater knowledge of Fintech than the others (Table 8).

Table 8.

Knowledge of Fintech * participants who worked or had worked in banking crosstabulation.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

The Mann–Whitney test was used to test Hypotheses 1 and 2 since the dependent variable was ordinal and the independent variable comprised several categories that defined independent samples. To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, the Wilcoxon test was used, as the samples were paired and the variables were ordinal.

The results show that knowledge of Fintech had a significant effect on the intention to change banks (Z = 4.65; p < 0.001; r = 0.35). The participants who knew about Fintech had a higher intention to change banks than the participants who did not know about Fintech (Table 9). Knowledge of Fintech explains 35% of the variability in the intention to change banks. The results support Hypothesis 1.

Table 9.

Mann–Whitney test results (H1).

The perceived security of Fintech had a significant effect on the intention to change banks (Z = 5.60; p < 0.001; r = 0.42). The participants who perceived Fintech as secure had a higher intention to change banks than the participants who did not perceive Fintech as secure (Table 10). The perceived safety of Fintech explains 42% of the variability in the intention to change banks. The results support Hypothesis 2.

Table 10.

Mann–Whitney test results (H2).

There were statistically significant differences in the perception of supervision in Portugal between traditional and Fintech banks (Z = 7.47; p < 0.001; r = 0.33). The perception of supervision in traditional banks was significantly higher than in Fintech (Table 11). The results support Hypothesis 3.

Table 11.

Wilcoxon test results (H3).

The results show that there were statistically significant differences in the perception of regulation in Portugal between traditional and Fintech banks (Z = 8.85; p < 0.001; r = 0.46). The perception of regulation in traditional banks was significantly stronger than in Fintech (Table 12). The results support Hypothesis 4.

Table 12.

Wilcoxon test results (H4).

5. Discussion

The main aim of this study was to understand people’s perceptions of Fintech, their level of knowledge, and the impact of its emergence on traditional banking.

Starting with the descriptive analysis of the variables under study, it was possible to see that only 32.8% of the respondents said they had good knowledge of Fintech. As previously mentioned in the literature, there was a moderately significant relationship between financial literacy and financial inclusion, which significantly impacts the acquisition of financial technology (Hasan et al. 2023). On the other hand, according to Sarabando et al. (2023), there is still a long way to go in this regard, with Portugal being identified as one of the poorest countries in Europe in terms of financial knowledge. In January 2022, the newspaper Público (2022) reported that the latest data from the European Central Bank for 2020 places Portugal at the bottom of the financial literacy ranking of the 19 countries in the Eurozone. Furthermore, the study by Sarabando et al. (2023), in which the sample was university students, revealed that several basic concepts were unknown to many. For example, two-thirds did not know what Euribor was, a similar percentage did not know what the spread was, and a third did not know what inflation was. Everyone in everyday life widely uses these concepts, but their meaning is still unknown to many since financial literacy in Portugal is not as good as it should be. For these reasons, it was expected that a large percentage of the sample would not know about Fintech.

When it came to the reasons for being a Fintech customer, there was a great deal of agreement regarding the lower costs and the fact that they provide greater convenience and ease of use. This aligns with the literature, which mentions flexibility, convenience, low cost (Nejad 2022), and faster and cheaper services (Martincevic et al. 2022). In addition, it is in line with the study by Fernandes (2019), where the sample was master’s students, and the two most-chosen reasons were lower costs and convenience.

As for why they were not customers of Fintech, most of the participants agreed that it was due to a need for more awareness of its existence and a preference for face-to-face and personalized service. Since knowledge about acquiring Fintech services significantly impacts access to them (Hasan et al. 2023), lack of knowledge aligns with the literature. It is the most apparent reason, since customers can only use something they know about. The reason for preferring face-to-face and personalized service is in line with the results of Fernandes (2019). Since Fintech companies do not have face-to-face services, the preference for face-to-face and personalized service is an obstacle that is very difficult to change due to the nature of these companies.

Regarding feeling more likely to use a Fintech after the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the participants said they disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement, with only 20% of the respondents agreeing (or strongly agreeing). In the literature, Versal et al. (2022) stated that digital banks were more sought after by families and individuals during the pandemic than traditional banks. However, in this case, the respondents had not been significantly impacted by the pandemic regarding using a Fintech.

Turning to the tests of independence, the results indicated that knowledge of Fintech is not independent of the participants’ gender, with the male participants having greater knowledge of Fintech than the female participants. Tripathi and Rajeev (2023) conducted a study using data from 109 countries looking at financial inclusion (a process of several stages, namely having a bank account, regular use, ease of making payments, and accessibility to financial services). In this study, the authors concluded that Portugal’s digital financial inclusion among women needs to be more satisfactory and that there is still a long way to go to improve the reach of digital financial services. These results may explain why knowledge of Fintech is higher among men. On the other hand, Chen et al. (2023) conducted original surveys from 28 countries and concluded that there is a gender gap in using Fintech services, with men using them more. However, this conclusion is contrary to the results obtained in this study.

Concerning knowledge of Fintech, it was found that the participants belonging to the “18 to 30 years” and “51 years and over” age groups were the ones with the greatest knowledge of Fintech and the ones who most often claimed to be customers of a Fintech. These results are partly in line with the literature. It states that young people are largely responsible for the transformation of digital financial technology and the paradigm shift in the mindset of banking consumers (Cahete 2020; Duarte 2019) and that the younger generations have a greater acceptance and use of these new technologies and are more inclined to use them than the older population (Martincevic et al. 2022). However, this study concluded that the older population, in this case, represented by the age group “51 years and over”, keeps pace with the younger age group “18 to 30 years” in both knowledge and use of Fintech.

Regarding the study of the hypotheses formulated, it was possible to confirm Hypothesis 1, regarding knowledge of Fintech having a significant effect on the intention to change banks. As previously mentioned in the literature by Hasan et al. (2023), financial literacy is essential for acquiring financial services, and knowledge of financial services impacts access to financial technology services. Thus, financial knowledge is one of the most relevant factors for promoting access to Fintech.

Hypothesis 2, concerning the perceived security of Fintech companies having a significant effect on the intention to change banks, was also confirmed. According to the literature, customers do not have much desire to change banks (Jones and Ozcan 2021) and would be more willing to do so when they feel familiar with the system, the usability is friendly, and the system works autonomously and is constantly updated (Cahete 2020). Although perceived security is not one of the factors named by the authors, it is understandable that this factor is relevant to the participants and that a greater perception of security leads to a greater intention to change banks.

Hypotheses 3 and 4, which refer to Portugal’s perception of supervision and regulation differing significantly between traditional banks and Fintech, were also confirmed. Indeed, financial markets are highly regulated, and the entry of Fintech companies has raised concerns and exposed the need to regulate them (Vučinić 2020; Martincevic et al. 2022; Eichengreen 2023). New regulations and guidelines have been introduced in various areas, and regulators have increased supervision and monitoring of the banking sector, ensuring that regulations are complied with, so the regulatory framework for the safety of the banking sector has evolved significantly since the emergence of Fintech (Gopal et al. 2023). However, the authors Ringe and Ruof (2020) consider that the regulatory framework in the European Union is of little help due to its slow evolution and adaptation, so the rules are both too much and too little inclusive, as they are difficult to adapt to Fintech activities. The rules are also applied in different ways in different member states. For this reason, the participants may have perceived that Portugal’s supervision and regulation were greater for traditional banking than for Fintech.

Financial education is compulsory by law, provided for in Decree-Law 139/2012, July 5. A document has been drawn up for this purpose, the Core Competencies for Financial Education, covering pre-school education, primary and secondary education, and adult education and training (Dias et al. 2013; Decreto-Lei n.º 139/2012, de 5 de julho 2012). However, despite this obligation, in at least two of the three cycles of education, several schools in the country chose not to provide this training to their students, even though many teachers reinforce this need (Andersson et al. 2024).

However, considering that the Core Competencies document dates to 2013 and the nature of Fintech, it is understandable that it does not reference them. Therefore, given that 10 years have passed since the document was drawn up, it is suggested that it be updated, considering Fintech and other innovations that have emerged in the financial market over the last few years, since we believe that the state represents a reliable source of information for educating on this subject as well. Fintech companies can also contribute to greater financial literacy through informative marketing campaigns, encouraging consumers to seek information about this innovation. In this way, even if they do not become customers of a Fintech, their financial knowledge has already been improved.

Limitations and Future Suggestions

In this work, some limitations to the study have emerged, and it should serve as a basis for future, more in-depth studies. One limitation is the sample size, which, despite having almost 200 participants, could have been more extensive and significant.

In addition, this study was limited to Portugal, so it might be interesting to carry out a study in different countries to compare the results later. On the other hand, the sample population was not defined, since the questionnaire was disseminated through social networks without any specification. Therefore, it could be interesting to study a well-defined population, as has been done by other authors.

Another suggestion relates to the possibility of a more in-depth study of other variables or those used in this study.

6. Conclusions and Contributions

The financial crisis experienced between 2008 and 2010 has been one of the factors responsible for financial change and innovation (Fabris 2022), which has brought new ways of providing financial services that are more efficient and convenient (Cahete 2020) and capable of creating lasting economic value for their customers (Tilman 2020). This development has played a vital role in banking development, especially in commercial banks (Li et al. 2022; Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022). An example of this impact is the emergence of financial technologies called Fintech (Taujanskaitė and Kuizinaitė 2022). Therefore, this study aimed to understand people’s perception of Fintech, their level of knowledge about it, and the impact of its emergence on traditional banking.

This study confirmed the results obtained by other authors. As mentioned, it was possible to see that knowledge of Fintech has a significant effect on the intention to change banks, with a large proportion of the respondents claiming they needed better knowledge of them due to Portugal’s low financial literacy. It was found that only 32.8 percent of respondents had a good understanding of what Fintechs are. As for the reasons for becoming a Fintech customer, lower costs and the fact that they provide greater convenience and ease of use were identified, as mentioned by other authors. Similarly, the most identified reasons for not being a Fintech customer were the lack of awareness of their existence and the preference for face-to-face and personalized service, which was very difficult to circumvent. However, in this study, COVID-19 did not significantly impact the participants’ willingness to use Fintech, which differed from the results presented by other authors.

Taking the results into account, it was also possible to see that the perceived security of Fintech has a significant effect on the intention to change banks. Thus, even though these companies invest heavily in security, consumers do not perceive this effort. Only 49.4 per cent of the respondents considered Fintechs to be safe. For this reason, Fintechs should continue to invest in their security and work on their image so that consumers can feel safe with them (for example, through marketing campaigns that reinforce this aspect). In addition, Portugal’s perception of supervision and regulation differs significantly between traditional banks and Fintech, with Fintech being perceived as less supervised and regulated. It will be in Fintech’s interest to continue working with regulators so that this sector makes progress in this area and that consumers can recognize greater equality between traditional banks and Fintech.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.M.; methodology, M.C. and M.A.-Y.-O.; software, A.M.; validation, M.C., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, M.C. and M.A.-Y.-O.; resources, M.C. and M.A.-Y.-O.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C. and M.A.-Y.-O.; writing—review and editing, M.C., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.M.; visualization, M.C., M.A.-Y.-O. and A.M.; supervision, M.A.-Y.-O.; project administration, M.A.-Y.-O.; funding acquisition, M.A.-Y.-O. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since all the participants before answering the questionnaire had to read the informed consent and agree to it. This was the only way they could answer the questionnaire. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, as well as that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known but would only be analyzed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data are not publicly available because in the informed consent form, the participants were informed that the data were confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all the participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abu Daqar, Mohannad A. M., Samer Arqawi, and Sharif Abu Karsh. 2020. Fintech in the eyes of Millennials and Generation Z (the financial behavior and Fintech perception). Banks and Bank Systems 15: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Pedro, Flávio Valente, and Catarina Coutinho. 2024. No poupar está o ganho: Saiba como os seus filhos podem aprender a gerir o dinheiro desde cedo. Sic Notícias. Available online: https://sicnoticias.pt/video/2024-04-10-No-poupar-esta-o-ganho-saiba-como-os-seus-filhos-podem-aprender-a-gerir-o-dinheiro-desde-cedo-cc1eb411 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Anshari, Muhammad, Munirah Ajeerah Arine, Norzaidah Nurhidayah, Hidayatul Aziyah, and Md Hasnol Alwee Salleh. 2021. Factors influencing individual in adopting eWallet. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 26: 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, Arnoud, Peter Hoffmann, Luc Laeven, and Lev Ratnovski. 2021. Fintech: What’s old, what’s new? Journal of Financial Stability 53: 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahete, Jessica Nazarina Miguel. 2020. Traditional Banking at Digital Age. Are They Keeping up with Changes in Consumer Behaviour? Millenials’ Perception in the Portuguese Market. Master’s thesis, Repositório Institucional do Iscte, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/handle/10071/22349 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Chen, Sharon, Sebastian Doerr, Jon Frost, Leonardo Gambacorta, and Hyun Song Shin. 2023. The fintech gender gap. Journal of Financial Intermediation 54: 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorzempa, Martin, and Yiping Huang. 2022. Chinese Fintech Innovation and Regulation. Asian Economic Policy Review 17: 274–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto-Lei n.º 139/2012, de 5 de julho. 2012. Diário da República n.º 129/2012, Série I de 2012-07-05. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/139-2012-178548 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Del Sarto, Nicola, Lorenzo Gai, and Federica Ielasi. 2023. Financial Innovation: The Impact of Blockchain Technologies on Financial Intermediaries. Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, António, Arnaldo Oliveira, Cristina Pereira, Maria Teresa Abreu, Paulo Alves, Rita Basto, Rosália Silva, and Susana Narciso. 2013. Referencial de Educação Financeira para a Educação Pré-Escolar, o Ensiono Básico, o Ensino Secundário e a Educação e Formação de Adultos. Ministério da Educação e Ciência. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ficheiros/referencial_de_educacao_financeira_final_versao_port.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Duarte, Susana Catarina Alves. 2019. Tendências Futuras do Setor Bancário. O Ajustamento da Banca Tradicional às Novas Tecnologias e a Banca Nativa Digital. Master’s thesis, Repositório Institucional da Lisbon School of Economics and Management, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://www.repository.utl.pt/handle/10400.5/19198 (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Eichengreen, Barry. 2023. Financial regulation in the age of the platform economy. Journal of Banking Regulation 24: 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, Nikola. 2022. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on financial innovation, cashless society, and cyber risk. Economics 10: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, Natália. 2023. Portugal está a envelhecer a um ritmo mais acelerado do que restantes países europeus. Público. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2023/02/22/sociedade/noticia/populacao-portugal-envelhecer-ue-revela-eurostat-2039817 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Fernandes, Carlos Canhoto. 2019. O desafio da Banca face às Fintech. Master’s thesis, Repositório Institucional do Iscte, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://iscte-iul.pt/tese/9451 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Galazova, S. S., and Leyla R. Magomaeva. 2019. The transformation of traditional banking activity in digital. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration 7: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorkiewicz, Lech, Jan Monkiewicz, and Marek Monkiewicz. 2020. Technology-driven innovations in financial services: The rise of alternative finance. Foundations of Management 12: 137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, Sanghmitra, Priyanka Gupta, and Amrisha Minocha. 2023. Advancements in Fin-Tech and Security Challenges of Banking Industry. Paper presented at 2023 4th International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM), London, UK, May 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, Christian, and Lars Hornuf. 2019. The emergence of the global Fintech Market: Economic and Technological Determinants. Small Business Economics 53: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Morshadul, Thuhid Noor, Jiechao Gao, Muhammad Usman, and Mohammad Zoynul Abedin. 2023. Rural Consumers’ Financial Literacy and Access to Fintech Services. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 14: 780–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesekova Bojmirova, Simona. 2022. FinTech and Regulatory Sandbox—New challenges for the financial market. The case of the Slovak Republic. Juridical Tribune 12: 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Ryan, and Pinar Ozcan. 2021. Rise of BigTech Platforms in Banking. Oxford: University of Oxford. Available online: https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-02/sustainability-report-2021-22.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Jornal de Notícias. 2024. Portugueses são os segundos piores da UE em literacia financeira. Available online: https://www.jn.pt/7598372527/portugueses-sao-os-segundos-piores-da-ue-em-literacia-financeira/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Jünger, Moritz, and Mark Mietzner. 2020. Banking goes digital: The adoption of Fintech services by German households. Finance Research Letters 34: 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, In, and Young Jae Shin. 2018. Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons 61: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Gang, Ehsan Elahi, and Liangliang Zhao. 2022. Fintech, Bank Risk-Taking, and Risk-Warning for Commercial Banks in the Era of Digital Technology. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 934053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincevic, Ivana, Sandra Črnjević, and Igor Klopotan. 2022. Novelties and benefits of fintech in the financial industry. International Journal of E-Services and Mobile Applications 14: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Karen, and Brayden McCarthy. 2017. How Banks Can Compete Against an Army of Fintech Startups. Harvard Business Review. April 26. Available online: https://hbr.org/2017/04/how-banks-can-compete-against-an-army-of-fintech-startups (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Moreira-Santos, Diana, Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira, and Ana Palma-Moreira. 2022. Fintech Services and the Drivers of Their Implementation in Small and Medium Enterprises. Information 13: 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-Visconti, Roberto, Salvador Cruz Rambaud, and Joaquin Lopez Pascual. 2020. Sustainability in Fintechs: An explanation through business model scalability and market valuation. Sustainability 12: 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, Mohammad G. 2022. Research on financial innovations: An interdisciplinary review. International Journal of Bank Marketing 40: 578–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, Carl. 2024. Fintech in Europe: A Comprehensive Overview. Eurodev. Available online: https://www.eurodev.com/blog/fintech-in-europe (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Peráček, Tomáš. 2021. A few remarks on the (im)perfection of the term securities: A theoretical study. Juridical Tribune-Tribuna Juridica 11: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Público. 2022. Portugal fica em último lugar no ranking de literacia financeira da zona euro. Available online: https://www.publico.pt/2022/01/13/economia/noticia/portugal-fica-ultimo-lugar-ranking-literacia-financeira-zona-euro-1991766 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ramlall, Indranarain. 2018. Fintech and the Financial Stability Board. In Understanding Financial Stability (The Theory and Practice of Financial Stability, Vol. 1). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringe, Wolf-Georg, and Christopher Ruof. 2020. Regulating fintech in the EU: The case for a guided sandbox. European Journal of Risk Regulation 11: 604–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabando, Paula, Rogério Matias, Pedro Vasconcelos, and Tiago Miguel. 2023. Financial literacy of Portuguese undergraduate students in polytechnics: Does the area of the course influence financial literacy? Journal of Economic Analysis 2: 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Mark N. K., Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2019. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed. New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Schueffel, Patrick. 2016. Taming the Beast: A Scientific Definition of Fintech. Journal of Innovation Management 4: 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taujanskaitė, Kamilė, and Jurgita Kuizinaitė. 2022. Development of fintech business in Lithuania: Driving factors and future scenarios. Business, Management and Economics Engineering 20: 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, Leo M. 2020. The Imperative of Financial Innovation. Harvard Business Review. June 1. Available online: https://hbr.org/2010/06/the-imperative-of-financial-in (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Tripathi, Sabyasachi, and Meenakshi Rajeev. 2023. Gender-Inclusive Development through Fintech: Studying Gender-Based Digital Financial Inclusion in a Cross-Country Setting. Sustainability 15: 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardomatskya, Ludmila, valentina Kuznetsova, and Vladimir Plotnikov. 2021. The financial technologies transformation in the digital economy. E3S Web of Conferences 244: 10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versal, Nataliia, Vasyl Erastov, Marija Balytska, and Ihor Honchar. 2022. Digitalization index: Case for banking System. Statistika 102: 426–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučinić, Milena. 2020. Fintech and financial stability potential influence of FinTech on financial stability, risks and benefits. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice 9: 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaoying, Ramla Sadiq, Tahseen Mohsan Khan, and Rong Wang. 2021. Industry 4.0 and intellectual capital in the age of Fintech. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 166: 120598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Gideon, and Alouis Madhikeni. 2013. Systems, Processes and Challenges of Public Revenue Collection in Zimbabwe. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 3: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).