Abstract

This research extensively discusses the connection between destination image and films influencing tourism. Despite the worldwide fame of the James Bond saga and extensive publications on the subject, research into the role of tourism promotion in the image of destinations is still scarce, and there is no specific focus on analysing promotional aspects in relation to film-induced tourism. This study focuses on the influence of cinematographic images on the destination image perception and promotion, specifically exploring the case of the James Bond saga as a practical case. With 25 films released since 1962, the James Bond saga provides a basis for evaluating cinematic presence in tourism promotion strategies. This research proposes the content analysis of the official tourist websites of 23 destinations where the James Bond saga was shot, which offer some tourist products linked to the saga. The key findings provide valuable insights into the promotion of James Bond saga tourism destinations, the role of films in promoting destinations, and the tourism products developed from the saga films. The results provide visual outputs about the target image of the film shooting locations, and the text analysis provides keywords linked to the theme. The study’s methodology contributes to the discourse on film tourism and destination image topics and brings practical and theoretical contributions to both academia and destination managers.

1. Introduction

Destination image is a key element in the success of tourism destination, influencing tourists’ decisions, trip quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioural intentions (Chen and Tsai 2007; Chi and Qu 2008; Li et al. 2023). This image can be shaped by audio-visual products such as films and series, giving rise to the phenomenon of “film induced tourism” (Riley et al. 1998; Beeton 2005; Croy 2011). New technologies have transformed the relationship between the film industry and tourism, and the popularity of audio-visual products, including video games, has increased the tourism potential of filming locations. In this way, the quality and wide dissemination of these products, especially on social networks, generate prolonged and repeated exposure to a particular place, impacting its tourism and economic performance (O’Connor 2011; O’Connor et al. 2008; Riley and Van Doren 1992).

The link between film-induced tourism and destination image lies in the influence that cinematic representations have on shaping people’s perceptions of a destination. When a place is featured in a film or television programme, it can have a significant impact on how the destination is perceived by potential tourists. Positive representations can improve the image of the destination, making it more attractive to visitors, while negative representations can dissuade tourists from visiting (Ahmed and Ünüvar 2022; Riley and Van Doren 1992; Josiassen et al. 2016). Such is the importance of destination image, where cinema-induced tourism can shape and be shaped by destination image. Filmmakers, on the one hand, can intentionally choose picturesque locations to increase the appeal of their productions, while destinations can promote their destinations through their film fame and improve their image (Riley et al. 1998; Beeton 2005; Connell 2005; Macionis and Sparks 2009; Zhou et al. 2023). Understanding this relationship is crucial for both destination marketers and filmmakers. Moreover, film-induced tourism is motivated by the desire to have cinematic experiences and, as Cardoso et al. (2019) point out, it creates images of dream destinations that tourists want to visit. The James Bond saga, known for its adventurous and traveling nature, can have a significant impact on tourism in the destinations featured in the films. Many fans of the saga may dream of visiting these locations to experience first-hand the settings where their favourite Bond scenes were filmed. The use of film in re-imaging a destination can be a powerful marketing tool (Yen and Croy 2016), and film tourism can provide sustained economic contributions to destinations (Croy 2011). However, the emphasis on cinema as an agent that induces tourism is still questioned, with the need for greater emphasis on its subtle influence and the role of promoting destinations to induce tourism (Juškelytė 2016).

Considering the above, this study follows the James Bond saga as a case study for analysing the promotion of the destination’s image for the reasons set out below.

The James Bond saga has had 25 films released since 1962, and some studies have used the Bond films in various areas (Chevrier and Huvet 2018). Some have focussed on cultural issues and history, such as Black (2000); others have examined the series’ response to global crises and the development of Bond’s character, such as Van der Merwe and Bekker (2018). Hochscherf (2013) analysed the dialectic between continuity and change in the first two James Bond films of the Daniel Craig era, framing them in a geopolitical and social context. Schwanebeck (2016) criticised the colonial legacy in the franchise, and Lindner (2009) provided a cultural and gender analysis. More recently, Ericksson and Jonasson (2023) emphasise the heroic character of James Bond. Using content analysis, Neuendorf et al. (2010) and Xiaozhen (2023) carried out a gender analysis of the role of women in James Bond films. However, considering the role that destination image plays in the development of a tourism destination, and as argued by (Liu et al. 2020), more research is needed to understand the film-induced tourism concept. So, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have specifically focused on analysing the promotional aspects of destination image in relation to film-induced tourism, highlighting an area yet to be explored. Given this gap, this study seeks to answer the following research question: how are James Bond films used to promote the image of the tourism destinations where they were filmed?

Based on this question, the use of films as promotional tools for tourist destinations is investigated, and this is the main objective of the work. To this end, the research uses a qualitative methodology based on the content of the official websites of the tourist destinations used in the James Bond saga. The results of the study identify 60 countries where the films were shot, provide valuable insights into the promotion of the destinations where the saga was shot, and identify some tourism products that have emerged as a result of the films.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Tourism Destination versus Destination Image and Imagery

The concept of “tourism destination” has a huge variety of meanings and depends on the different positions and objectives of the researchers investigating it, as well as the different representations of the multiple actors in the tourism system who use the term to designate very different, sometimes contradictory realities, such as a tourism attraction, a geographical entity, a marketing object, a narrative, a place where the tourist experience takes place, etc. (Jovičić 2019; Almeida and Almeida 2023).

Considering the enormous variety of approaches that exist in tourism literature, it is possible to identify a conceptual differentiation in two positions: the supply perspective and the demand perspective. From a supply-side perspective, a destination is a geographical territory defined and promoted as a single entity with a political and normative structure for tourism marketing and planning (Buhalis 2000; Jovičić 2019). From the perspective of demand, a tourism destination is the place where the tourist experience takes place, as well as the set of devices that make it possible, referring to the perceptions that tourists and potential tourists develop about tourist places. From this point of view, a tourism destination is a perceptual concept that can be interpreted subjectively by tourists (Buhalis 2000; Gretzel et al. 2018; Croy 2010). So, in this context, tourists perceive destinations as brands related to a set of services and possibilities for experiences (Almeida and Almeida 2023). Therefore, the most appropriate definition of a destination is that proposed by Murphy et al. (2000, p. 44): “an amalgam of products and experience possibilities that are combined to provide a total experience in the area of visit”, which is also defended by Buhalis (2000). Whatever concept of destination is adopted, there is no doubt that destination images play a decisive role in tourists’ choices (Dias and Cardoso 2017). According to Hunter (2016), studies in this field tend to focus on three complementary topics: (1) imagery; (2) destination image; and (3) how the perceived destination image is affected by marketing campaigns and destination experiences. The duality of image versus imagery has accompanied studies on this subject for decades; however, the study by Cardoso et al. (2019) paves the way for understanding this duality. These authors describe destination image as a global composite that synthesises the cognitive and affective evaluations of a tourism destination; in contrast, imagery is described as the processing of the image in short-term memory. The imagery of a destination thus corresponds to the set of perceptual elements about that destination that are cognitively processed at a given moment (Josiassen et al. 2016) and that can either derive from external stimuli or from cognitions that are retrieved from long-term memory (Cardoso et al. 2019). Therefore, when it comes to tourists’ perceptions of a tourist destination, understanding the role of the image and imagery of destinations and their influence on the process of choosing destinations is crucial (Morrand et al. 2021). In order to understand this relationship, it is necessary to understand the process of image formation.

Several researchers (Gartner 1994; Baloglu and McCleary 1999, among many others) assume that image is a dynamic construct that is gradually consolidated in long-term memory. This process is subject to the influence of various induced stimuli (directly linked to the promotion of the destination) or organic stimuli (linked to the experience and co-creation of the image); in other words, it depends on a continuous processing of the image that is referred to as imagery.

2.2. The Role of Films in Tourism Destination Image

Several researchers have explored how the film industry contributes to making certain places prominent tourism destinations (Riley and Van Doren 1992; Kim and Richardson 2003). Since the 1990s, several authors have recognised the influence of visual media on tourism destination image (Butler 1990; Schofield 1996; Michopoulou et al. 2022; Morgan and Pritchard 1998; Croy and Walker 2003; Kim and Richardson 2003). These visual media encompass various techniques and forms, such as painting, drawing, photography, brochures or catalogues, technologies (El Archi and Benbba 2023; El Archi and Benbba 2024) and, of course, films and series. Destination managers have noted the increasing importance of film and other audio-visual media, and more and more destinations are opting for this form of promotion (Kaikati and Kaikati 2004; Russell 2002). Destinations have the opportunity to highlight the most attractive aspects through films, thus influencing the perception of the destination’s image according to the vision that the site managers want to convey. These media are considered highly influential due to their inductive and less intrusive nature compared with conventional advertising (Hudson and Ritchie 2006; Hudson et al. 2011; Rodríguez and Brea 2010). Although film tourism has experienced significant growth in recent years, its exact measurement remains a challenging phenomenon (Busby and Klug 2001). Cinema plays a fundamental role as a key source of information for the formation of images of tourism destinations. This function takes on significant importance as visual representations have a decisive influence on tourists’ choice of destinations (Rodríguez-Molina et al. 2015). As advocated by Giraldi and Cesario (2017), cinema has highlighted the significant influence of films on tourist visitation and destination image, with cinema often being a crucial factor in tourism decision making. In the last decade, there have been significant advances in research on film tourism. In contrast to the first studies in the 1990s, which approached this novel phenomenon from the perspective of the benefits derived from tourism activity in destinations, especially in relation to film (Riley et al. 1998; Tooke and Baker 1996), research since 2000 has delved considerably deeper into this specific form of tourism (Connell 2012).

Focusing on the benefits for destinations appearing on screens, be it in films or series, above all, we should mention the active involvement of the audience, which is considered as a crucial element in the use and impacts of media, representing a fundamental characteristic of active audiences who proactively seek out and experience media to meet expectations and needs in the field of media communication (Kim 2012). When the audience is deeply involved, the film viewing experience can be transformed into something memorable and rewarding. The audience’s emotional involvement in viewing films and series can contribute to improving the perception of the tourism image of a specific film location (Dubois et al. 2021). Films and series, when broadcast as cultural expressions and presented publicly, allow direct contact with the rich cultural atmosphere of the filming location, generating a sense of belonging in the audience (Wen et al. 2018). Consequently, cultural contact plays a significant role in the relationship between audience participation and their perception of the image of tourist destinations.

2.3. Film-Induced Tourism or Film Tourism—A Duality to Consider When Analysing the Promotion of Tourism Destinations

Film-influenced travel has experienced a remarkable increase in recent decades, establishing itself as a global phenomenon (Yen and Croy 2016). Towards the end of the twentieth century, a number of scholars engaged in a more in-depth analysis of this type of tourism (Beeton 2006; Busby and Klug 2001; Tooke and Baker 1996). Araújo Vila et al. (2021) state that some researchers have created conceptual distinctions between the concepts of film tourism and film-induced tourism. The former refers to visits to places used or associated with filming, as defended by Buchmann et al. (2010), and it refers to the phenomenon in which tourists visit a destination because it has been featured prominently in a film or television series. From this point of view, the concept centres on the act of travelling to places specifically because of their appearance in the popular media, regardless of whether intentional efforts have been made by destination marketers to promote them. Film-induced tourism, although also involving visiting destinations portrayed in films, goes beyond mere viewer interest, and it includes intentional efforts by destination marketers or tourism boards to capitalise on the popularity of films to attract tourists. This term highlights the proactive role of destination stakeholders in capitalising on a location’s cinematic appeal to promote tourism. In other words, as Croy (2011) points out, it is a type of tourism influenced by promotion. In this category, Beeton (2005) also includes visits to production studios as well as film-related theme parks. Kim and Wang (2012) advocate the term “screen tourism”, while Ward and O’Regan (2009) highlight another market opportunity arising from the relationship between tourism and film: the provision of film and television production services to independent producers. From a global perspective, destination marketing organisations and local economic development agencies have implemented various film-induced tourism initiatives with the aim of enhancing the reputation of film locations, increasing awareness among visitors, and increasing the number of tourists (Connell 2012). The effectiveness of these initiatives has been confirmed by the finding that the films have not only changed or improved the perception of the featured destinations in the minds of tourists but also stimulated their participation in film-related activities (Volo and Irimiás 2016). As defended by Riley et al. (1998), this type of tourism is often motivated by the desire to relive cinematic experiences and can be influenced by factors such as novelty, prestige, and personalisation.

As a result of this phenomenon, it is common to observe a significant increase in the number of visitors to film locations after the release of a film (Singh and Best 2004). Films such as The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Slumdog Millionaire, and City of God have had a notable but unnoticed impact on tourism trends, generating a considerable increase in the influx of tourists to filming destinations in various parts of the world. According to Wen et al. (2018), in India, the release of Slumdog Millionaire in 2008 generated unprecedented international attention to Mumbai’s slums, giving rise to what is known as “slum tourism”. Following the film’s success, Indian slums began to appeal more obviously to consumers as exotic tourism destinations, departing from conventional tourism routes (A. C. Mendes 2016). Similarly, the release of City of God in 2003 had a similar effect in Rio de Janeiro, leading to citywide tours that allowed visitors to explore the favelas they had seen on screen (Freire-Medeiros et al. 2011). And in New Zealand, The Lord of the Rings filming locations experienced a notable increase in tourist interest (Suni and Komppula 2012). Indeed, the role of cinema in shaping destination images and motivating travel is increasingly recognised, as Macionis (2008) argues, and the potential of film-induced tourism has been explored in various locations, including Ireland (Bolan and Davidson 2005) and Seville, Spain (Oviedo-García et al. 2016). Thus, film-induced tourism highlights the deliberate promotional efforts of destination promoters and, as Cardoso et al. (2017) point out, more studies are needed to clarify this concept. For the purposes of this study, the term “film-induced tourism” will be used due to its wide use in the literature and its broader scope.

2.4. James Bond Saga

Ian Fleming, a former member of the British Intelligence Service during World War II, was the creator of James Bond. Fleming sold the Casino Royale (Campbell 2006) story to the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) for USD 6000. In 1954, Barry Nelson characterised Bond as an American hero. From then on, Fleming began writing the exploits of Agent 007 with the intention of adapting them for film. He developed settings, characters, violence, and a touch of snobbery, creating a perfect formula to reflect the atmosphere of Cold War Europe. A selection process was held for the role of James Bond, and Sean Connery was chosen to play the British agent in the first films. After You Only Live Twice (Gilbert 1967), Connery announced his retirement from the project. George Lazenby succeeded him and starred in the only film he casted as the secret agent, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Hunt 1969). Despite being cast in several films, Lazenby was not as successful, and to remedy the situation, Eon Productions again negotiated with Connery, who starred in Diamonds Are Forever (Hamilton 1971). After this film, Connery stated that he would never play Agent 007 again, but in 1983, he returned in Never Say Never Again (Glen 1983a), although this film is not considered official. After Connery’s resignation, Roger Moore was chosen to play the secret agent, and he is considered by many to be the best Bond ever (Chapman 2024; Field and Chowdhury 2015).

To market the Bond films, EON Productions (which produced 23 of the 26 Bond films) created a dynamic male brand identity for its lead character. They brought to the screen a man with a strong personality accompanied by a lifestyle that highlighted all that was forbidden about bachelorhood, sexual voyeurism, and adventure (Weiner et al. 2011).

After the seven films starring Roger Moore, the production opted to give the role to Pierce Brosnan. However, Brosnan declined the offer due to the restrictions of another television contract that prevented him from doing so. It was then that Timothy Dalton received his chance, starring in The Living Daylights (Glen 1987) and Licence to Kill (Glen 1983b). It seemed that the story of the British agent was coming to an end, as Dalton’s films were not as successful as expected. However, the saga was miraculously revived with GoldenEye (Campbell 1995), starring Pierce Brosnan, who went on to appear in three more films in the franchise.

In 2006, Daniel Craig took on the role of the British agent, marking a true beginning to the legend with Casino Royale (Campbell 2006), followed by Quantum of Solace (Forster 2008), which was the 22nd film in the saga. Craig continued to play James Bond in Skyfall (S. Mendes 2012), Spectre (S. Mendes 2015), and finally No Time to Die (Fukunaga 2020). The saga of the silent agent began on the big screen in 1962 with the adaptation of the fourth novel, Dr. No (Young 1954) and has endured to the present day with a total of 25 official films produced by Eon Productions. In addition, there are two unofficial films, Casino Royale in 1967 and Never Say Never Again in 1983. According to McInerney (1996), the Eon series is one of the most lucrative franchises in history.

The popularity of the James Bond films has persisted over the years and has featured several actors playing the iconic British secret agent, with Sean Connery, Roger Moore, Pierce Brosnan, and Daniel Craig being some of the most prominent performers. James Bond films are known for their thrilling action scenes, intriguing plots, innovative gadgets and, of course, the charismatic title character. Each new instalment in the series usually generates excitement and box office success, a phenomenon that can benefit the destinations featured in each instalment. Moreover, product placement has been present in the saga since its inception, whether through various products or through the destinations viewed (Nitins 2011).

DMOs (Destination management organisations) are increasingly aware of the importance of the use of films and other audio-visual products (e.g., series) for the promotion of destinations. Film tourism has moved from film tourism to screen tourism, given the impact on viewers of films, series, video games, etc. (Sanz 2023).

Thus, in 2015, one of the main destinations of this saga, the United Kingdom, already bet on the film released that year, Spectre, as a promotional tool. The “Bond is GREAT Britain” campaign, in collaboration with Sony Pictures Entertainment and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios, was carried out in more than 60 countries “with the aim of encouraging fans of Agent 007 to choose Great Britain—the home of James Bond—to enjoy their next vacation”, as explained by the official British tourism agency. VisitBritain’s international campaign used outdoor, print, and digital media as well as social media. Among the novelties of this campaign were four new 360° images of the main filming locations, including Blenheim Palace, Camden, Westminster Bridge, and London’s City Hall, to be disseminated internationally through VisitBritain’s social networks. Another promotional campaign was run in 2012 ahead of the Skyfall premiere, “Bond is GREAT”, which achieved promotional media coverage reaching 653 million people worldwide, according to Visit Britain (2020). Around 16% of the “Bond is GREAT” audience booked a trip to Britain, and 35% stated their intention to visit the country in the next three years. In addition, Skyfall helped increase visitors to Glencoe, Scotland, by 41.7% in 2012 after it was used as a film location (Visit Britain 2020).

3. Methodology

In order to analyse how the films in the James Bond saga are used to promote the image of the tourism destinations where they were filmed, and to fulfil the research question, the following objectives were set:

- Identify the countries with the highest film production and check the official websites for visual and written communication about the films;

- Identify the countries with the highest film production and check official websites for visual and written communication about tourism products related to films;

- Identify in the countries with the highest film production the destination image promoted related to James Bond saga.

In the 3 objectives, we reference the countries with the highest film production; i.e., the aim is to locate which countries have made the most active and intense use of the James Bond saga as a promotional tool, a conscious and purposeful use of the film as a promotional medium, and not something random or casual.

The methodology applied is a case study using the technique of content analysis. This type of methodology is appropriate in the case of film-induced tourism (Beeton 2009). In the empirical work of this paper, and in order to meet the research objectives, a qualitative approach was adopted, also using a quantitative component to analyse the written content based on the Cardoso et al. (2017) methodology. The content analysis technique was adopted in this study and applied to the analysis of official websites. According to Berelson (1982, p. 18), it is “a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication”. For Holsti (1969, p. 5), “content analysis is a research technique for formulating inferences by systematically and objectively identifying certain specific features within a text”. And for Krippendorff (1990, p. 28), it is “a research technique designed to formulate, from certain data, reproducible and valid inferences that can be applied to their context”.

The content analysis approach used in this work is that of Bardin and Shumeiko (1977); the approach involves a set of tools with the purpose of analysing communication that can be extracted from its descriptive procedures and objectives. Messages contain a content that allows for an understanding of a perceptual relationship on the subject matter. Even more, content analysis has an exploratory purpose, which seeks to discover or verify communications on a specific topic. Therefore, this analysis technique can be used to classify or categorise content, information, knowledge, and communications. It involves translating key elements and comparing them with other elements. In this way, a content analysis contributes to the description of the content of a communication disseminated by any means, be it newspapers, films, websites, conversations, or verbal expressions.

The categories used in this study follow the methodologies of Cardoso et al. (2017) and are applied in three stages: (1) pre-analysis: this stage explores the method, material and data to be processed; selects the type of data to analyse (visual or text) and type of software if required; elaborates indicators; and prepares the material for analysis; (2) aggregation of material for analysis: data must be organised and aggregated into units; and (3) data processing: interpretation. The researcher must confront their results with the theory used to make them meaningful, in addition to discussing the relationship between the observed results and the accumulated knowledge in a given area of research.

3.1. Pre-Analysis Phase Procedures

The application of content analysis to the image of a tourism destination in cinematographic films has been widely studied in the field of tourism and with great incidence in the analysis of websites (Laba 2018; Rodríguez-Molina et al. 2015). Furthermore, Kim et al. (2017) and Govers and Go (2004) argue that analysing the image of a tourism destination in website content is a useful methodology for analysing the projected image of tourism destinations. In choosing the type of website for data collection, this study considered the government tourism websites of the countries, considering their reach according to Farias (2013). For this reason, this research chose the government websites of 37 countries and 40 cities where the films were shot as the source of data collection. To choose the analysis sample, after identifying the destinations where the James Bond saga films were filmed (identified in Table 1), as a criterion for inclusion, only destinations where the words “James Bond” or “James Bond Saga” appeared in the website’s search engine were considered.

Table 1.

Official websites of 007 saga tourism destinations analysed.

The analysis variables used in this study are based on several authors; the website design and ease of access to information are based on Govers and Go (2004) and Rodríguez-Molina et al. (2015). The information provided on the website comes from Kim et al. (2017) and Farias (2013), who argue that the destination’s website is the virtual place where potential tourists can experience some attributes of the tourism service by visualising the cultural characteristics of the film tourism product and where the offer of tourism products related to the James Bond saga films can be provided (Luštický et al. 2020). Furthermore, Macionis (2008) and Rahman et al. (2019) argue that the film tourism product website is the place where the image of the tourism destination is induced. In destination websites, the following variables used were: (1) the 007 film in the main menu (direct access to information or access after use of search engine); (2) the type of text and image used; and (3) the tourism products related to the 007 film (images and text). In this qualitative phase, the researcher’s subjectivity was also taken into account as several authors warn against this detail in qualitative analyses (Cardoso et al. 2017).

The content of the collected text located next to the images and products related to the 007 saga films was analysed and characterised using a quantitative approach by the frequency of occurrence (Nosenko 2022).

3.2. Aggregation of Material for Analysis and Data Processing Interpretation

Data aggregation from the qualitative content analysis was performed in a word file in a table, and its interpretation is presented in the Section 4. The text data were aggregated into a TXT file and analysed using DB Gnosis software (this software is free and available via the Centre for Tourism Research, Development and Innovation—CiTUR Leiria). The text data were subjected to categorical content analysis applying Zipf’s law and processed by frequency of occurrence, as performed by Cardoso et al. (2017) and Moreno-Sánchez et al. (2016). The processing and results of this analysis are presented in the Section 4 of this paper.

4. Results

4.1. Visual Destination Image of the James Bond Saga Destinations with the Highest Film Production

4.1.1. United Kingdom

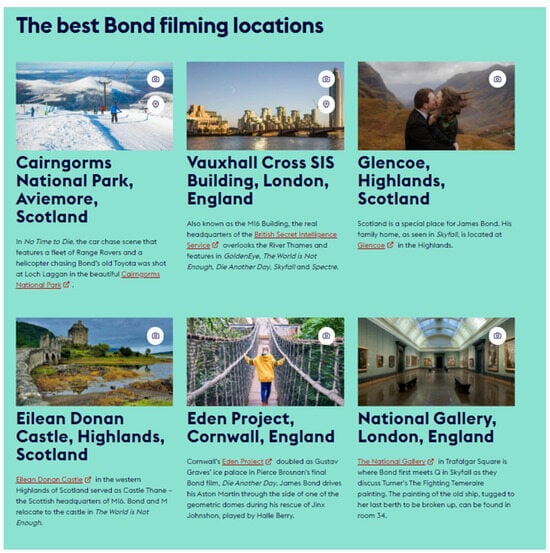

The United Kingdom is the destination par excellence associated with the James Bond saga, present in several of the instalments of the famous 007 agent. After analysing the main menus of the official tourism website under “Things to do” (second menu), we found a direct access to the filming locations of Harry Potter but not James Bond. A direct search using the key words “James Bond” in the web search engine led to two possible accesses: James Bond filming locations (Figure 1) and Great Britain on screen, both of which already indicate the interest of this destination in film tourism and the specific case of the James Bond films.

Figure 1.

Locations in the United Kingdom.

4.1.2. London

No specific menu or image appeared on the main screen about the film or the film tourism category in general. After using the search engine to search for the keywords James Bond, two results appeared: “James Bond walking tour” and “Madame Tussauds London”. The first entry provided the option to purchase a walking tour route, with little information about it. Madame Tussauds London provided us information about the museum, location, contact, ticket price, opening hours, and a brief description of two films.

4.1.3. Buckinghamshire

On the website, there were three mentions of James Bond filming locations in Buckinghamshire: Pinewood Studios, Stoke Park, and Waddesdon Manor.

In addition, other mentions of locations such as Black Park and Bletchley Park, although not exclusively related to James Bond films, indicate the diversity of filming options offered by the destination.

4.1.4. Blenheim Palace

On the official Blenheim Palace website, there was no direct mention of James Bond films. When you search for “James Bond” in the site’s search engine, only a news item entitled “Lights, Camera, Action! Trail” was returned. However, it is important to note that the name of the film was listed alongside other titles, such as Harry Potter, suggesting that the news item covers various film productions conducted at Blenheim Palace and does not focus exclusively on the James Bond saga.

4.1.5. Switzerland

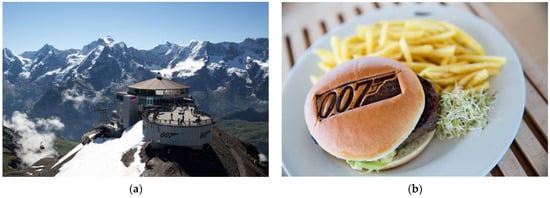

The first search on this website found no images or text related to films. A second search for the keywords “James Bond” yielded 29 results. Of the 29 results, 8 of them were tourism experiences, such as a fictitious audition to become the next James Bond with tests, races, photo shoots, or a Martini workshop; a visit to the famous “Bob Run”, where part of the James Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was shot in 1969 (Hunt 1969); or a cable car ride up the Piz Gloria. Seven routes were also presented, including the Grütschalp-Mürren-Weg, a panoramic hike at high altitude over the steep Lauterbrunnen valley with views of the Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau peaks; and the Apollo Run, a chairlift ascent. In addition to routes and experiences, accommodation, venues, and restaurants were featured. A highlight was the Schilthorn Piz Gloria, featured in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Hunt 1969), the most Swiss James Bond film, as most of it was shot in the Bernese Oberland. The famous setting of the 1969 film was the world’s first revolving restaurant, to which the name Piz Gloria has since been added (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Piz Gloria restaurant in Switzerland. (a) Exterior of the revolving restaurant; (b) dish in honour of Agent 007 on the restaurant’s menu.

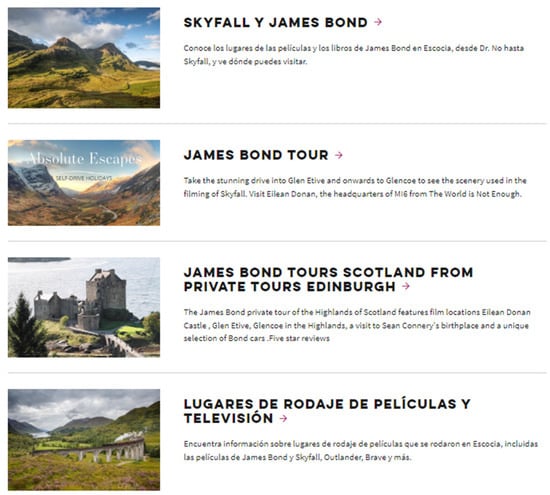

4.1.6. Scotland

Searches for the keywords mentioned above turned up images of four filming destinations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Destinations of the James Bond saga in Scotland.

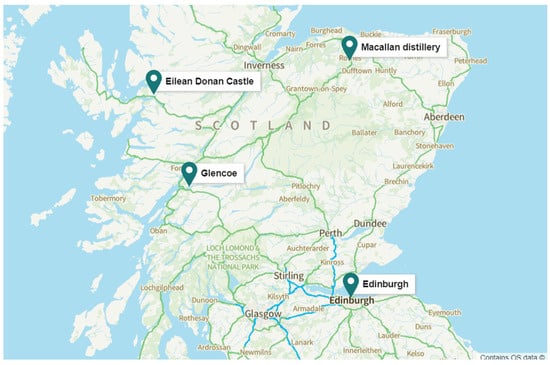

Of particular note was a tourist map showing the filming locations. In the film Skyfall, Scottish destinations are mentioned, such as Glencoe, and there are destinations that are linked to the film in the James Bond saga, making it possible to book accommodations online, such as: Edinburgh, Scotland’s West Coast, Macallan Distillery, Castillo Eilean Donan, Glen Etive, and Glencoe in the Highlands (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Movie map of James Bond in Scotland.

4.1.7. The Sardinia

On the Sardinia website, the mention of the James Bond film was quite subtle, without specifically highlighting which film was produced in the region. The main focus of the release was on the beaches of the village of San Pantaleo. The only reference to James Bond was found in a sentence that included various pieces of information, where it was mentioned that the village is known as “the village of artists”.

4.1.8. Venice

The city of Venice is often featured in James Bond films. However, the site offered little information about locally produced films. Searching for the name of the film’s protagonist on the site’s search engine returned eight results, but these consisted of brief mentions of the saga without giving it any significant prominence. The destinations mentioned in the results found included:

- ▪

- Rialto and San Marco, with reference to the film Casino Royale (Campbell 2006);

- ▪

- Monumental churches, synagogues, and Scuole Grandi, highlighting a multicultural environment in Cannaregio, mentioning the film Moonraker (Gilbert 1979);

- ▪

- Medieval San Polo, also mentioning the film Casino Royale (Campbell 2006);

- ▪

- Palazzo Fortuny, mentioning the film Casino Royale (Campbell 2006).

4.1.9. Jamaica

On the Jamaica tourism website, there was no mention of film tourism or James Bond on the home page or any of the main menus. In this case, when using the search engine, there were four results obtained. Two of them were linked to GoldenEye (Campbell 1995), Laughing Waters, and the Roaring Pavilion. Through the first access to GoldenEye, one can book James Bond’s house in Oracabessa, where one can also find the house of the creator of the iconic James Bond novels, Ian Fleming, who also became a tourist attraction.

4.1.10. France

On the france.fr website, there was only a press release about the 007 saga entitled “From James Bond to high Gothic”, with the Chateau de Foix illustrating the text. The mention of the James Bond films is summed up in a single sentence: “Peyragudes, the location for the crucial summit finish in the Pyrenees, is a renowned snowboard resort that also appears in the James Bond film, Tomorrow Never Dies (Spottiswoode 1997)”.

4.1.11. Paris

As in the tourist websites analysed so far, one must proceed directly to the search engine to obtain information related to the saga, obtaining four results. The exhibition Top Secret (State Secret), which explored the theme of espionage in cinema, was open until May 2023. Presented at the Cinémathèque from 21 October 2022 to 21 May 2023, it highlighted the films, actors, and actresses who have played the role of a spy, whether fictional or historical, for characters ranging from Mata Hari to James Bond. There were no specific results for any of the films, but in the entry “Top 10 filming locations”, James Bond: Moonraker was mentioned in fifth place, with Renzo Piano’s Pompidou Centre being the most important filming location. Finally, in the entry “Luxury Casting from the Parc Monceau to the Tour Eiffel”, one of the 007 films was mentioned, making a proposal: lunch or dinner at the Jules Verne, 125 metres above sea level, like Roger Moore in A View to a Kill, opus 14 of the James Bond series.

4.1.12. Spain

On the Spanish website, there were three results linked to James Bond. “Almería, playas y planes de película” mentioned two beaches where sequences from the James Bond film “Nunca digas nunca digas nunca jamás” were filmed. La Caleta beach was mentioned, which has appeared in the film Die another day (Tamahori 2002); and in “How much do you know about the beaches and coasts of Spain?”, there was a 10-question test on this subject.

In the culture menu, there were releases on “Film and TV destinations in Spain”, mentioning other series and films with a greater presence in this country, such as Madrid in La Casa de Papel and the Canary Islands in The Witcher or Game of Thrones.

4.1.13. Miami

In the case of the Miami tourism website, the information linked to James Bond was not very significant. After performing a search on it, only two results were obtained:

Bleau Bar: this is the signature bar at the legendary resort where James Bond and Goldfinger played a game of gin rummy;

Hotels with amazing pools: the Fontainebleau Miami Beach, where the first scene of James Bond’s Goldfinger (Campbell 1995) was filmed, appears in the list of hotels.

4.1.14. Thailand

After navigating through the main menus of the website, we were unable to access information on James Bond, so we performed a direct search, obtaining in this case only one result: See and Do. Ko Tapu (James Bond Island). Information on the link to the film is as follows: “In 1974, this beautiful Island was a location in a James Bond film “The Man with the Golden Gun” (Hamilton 1974), hence its name. The island belongs to the Ao Phang Nga National Park and is also known as ko Tapu) and location”.

4.1.15. Sölden

On the website’s homepage, there were two references to James Bond films, both related to a film installation in the Alps called “007 Elements”, which opened in 2018, associated with the film Spectre (S. Mendes 2015). “007 Elements” features videos, sound effects, interactive stations, and Bond gadgets, with the aim of “inspiring tourists”.

4.1.16. Bahamas

When the term “James Bond” was entered into the site’s search engine, several links were displayed, but many of them were repeated. One of the links referred to the Thunderball Grotto, also known as the “James Bond Grotto”. Another mention on the site is of the 2006 film, Casino Royale (Campbell 2006), where it was pointed out that “The Martini Bar” was built on the site, famous for Agent 007’s “Vesper Martini” drink. In addition, “50 Reasons to Love the Bahamas, celebrating 50 Years of Independence” was presented, where number 36 highlights the Exuma Islands, the National Land and Marine Park, and James Bond’s adventures in the Thunderball Grotto.

4.1.17. Nassau

On the Nassau website, there was a page with 34 results when searching for the term “James Bond”, associated with the Nassau Paradise Island. One of the highlights was an announcement about the celebration of “Global James Bond Day on 4 October”. Two films were specifically mentioned, Thunderball (Young 1965) and Never Say Never Again (Kershner 1983), which feature shipwrecks, such as the Tears of Allah, and a bomber plane, the Vulcan, both of which serve as backdrops for the Bond saga. There is also a mention of a “Martini Bar” associated with the character.

4.1.18. Hong Kong

In the website search engine, two links related to Agent 007 appeared. One of them is the “Hong Kong Pop 60+ Exhibition Audio Tour Script”, referring to a game from the film Goldfinger (Hamilton 1974). It is interesting to note that the 1962 James Bond film served as the inspiration for a series locally known as “Lady Bond”, which was a female version of the Secret Agent. The website mentions that “Lady Bond” was Hong Kong’s first James Bond-style suspense and espionage film, but starring women.

4.1.19. Berlin

In Berlin, the only mention of a Bond film on the website was associated with Oc-topussy (Glen 1983b). The film, released in 1983, highlights the Checkpoint Charlie border crossing as one of the saga’s iconic scenes.

4.1.20. Iceland

On the Iceland website, only one result was found, referring to the Svínafellsjökull glacier. This destination was featured in the opening scene of the James Bond film Die Another Day (Tamahori 2002).

4.1.21. Czech Republic

In the website’s search engine, three results were found, but only one destination was mentioned, the Hotel Splendide, without referring to the name of the film.

4.1.22. Chile

In the website’s search engine, the reference found was to the film Quantum of Solace (Forster 2008), filmed on the outskirts of Antofagasta. The title of the release found was “007 in the driest desert in the world”, referring to the Atacama Desert. However, the text highlighted two other destinations that appear in Bond’s film: the old Baquedano railway station and the port of Cobija.

4.1.23. Monaco

In the website’s search engine, the name “Monte Carlo Casino” was associated with the name of James Bond. However, in the aforementioned press release, entitled “James Bond style atmosphere”, only the luxurious style of the 007 character was referred to, without highlighting the location.

4.2. Text Destination Image Promotion of the Bond Saga Destinations with the Highest Film Production

According to Cardoso et al. (2017) and Moreno-Sánchez et al. (2016), the authors argue that based on Zipf’s law, there are three-word categories in texts: (1) high-frequency words or “stopwords”, operational words like articles, pronouns, conjunctions, prepositions, and some adjectives and adverbs; (2) average-frequency words, carrying more ethymological and informative representations, such as substantives, adjectives, and verbs; and (3) unit-frequency words, terms occurring in very specific contexts with frequencies of one or close to one. Thus, by eliminating the stopwords and performing a top 20 ranking, we obtained the words that were linked to the topic, which are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Text destination image promotion of the Bond saga destinations.

In relation to tourism products, the words “ticket”, “experience”, “ski”, “place”, “walking tour”, “adventure”, “book”, “unique visit”, and “tickets” showed a link to the existing tourism products in the destinations. Words such as “famous”, “unique”, “see”, and “visit” are communicative appeals for the promotion of the tourism products involved.

There were also associations with tourism destinations through the words “Palace”, “World”, and “Mountain”, which indicate generalised locations. On the other hand, “Cannes”, “City”, “Blenheim”, “Cadiz”, “Basilica”, “Castle”, and “Iceland” indicate specific cities or places that have been featured in some Bond films. “Visit” and “See” were also included in the reference to destinations, as well as tourism specifically. However, there were words that indirectly refer to the films in the franchise and also to destinations, such as: “Walking” (related to Tour), “Martini” and “Restaurant” (related to Hotel), and Beach (related to adventure and exploration, as in James Bond Island). These observations emphasise the influence of keywords on the perception of tourism destinations. As pointed out by Chagas and Dantas (2009), the careful choice of these words can significantly influence tourists’ decisions when selecting a destination. Thus, the words identified as most frequent on the websites of destinations associated with the James Bond saga are considered key elements for an effective local tourism marketing strategy. At the same time, words, like images, are part of the construction of a destination’s image, as validated in previous studies (Chagas and Dantas 2009; Mano and Costa 2018; Ramos et al. 2021; Sandi and Baptista 2024).

5. Discussion

5.1. Countries with the Highest Film Production and Official Websites Communication about the Films

The United Kingdom stands out as the leading country in the production of films in the James Bond saga. This is followed by Italy (21 films), England (14), and the United States (13), consolidating their position as significant countries in Agent 007’s cinematic narrative. When we compare the geographical distribution of the James Bond films with the ranking of the most visited countries in the world, we realise that the film locations coincide with popular or exotic tourism destinations.

The James Bond saga, recognised for portraying a sophisticated and mysterious lifestyle, offers destinations a unique association with cinema (Cardoso et al. 2019), giving them a reputation (Almeida and Almeida 2023). Places like Monaco, the United Kingdom, and Scotland, which have served as backdrops for James Bond’s adventures, benefit from the projection of this lifestyle, attracting tourists. In this way, the role of film locations reflects and reinforces the style of the films and main characters, influencing the viewers’ perception of the destinations portrayed. Destinations that actively embrace their connection to the Bond saga often benefit from more exposure. On the other hand, destinations that choose not to capitalise on this association may have other reasons, such as protecting their cultural identity or avoiding mass tourism.

Countries with more film production invest in tourism promotion associated with the James Bond saga. The connection between films and destinations is evidenced by the presence of specific websites dedicated to this theme, suggesting that the tourism industry recognises the potential of films as a tourism promotion tool (Vagionis 2011).

5.2. Countries with the Highest Film Production and Official Websites Communication about the Tourism Products

In addition to being works of fiction, films are marketing tools (Vagionis 2011). The James Bond saga exemplifies this role when it generates an increase in tourism at the filming locations, but also by giving rise to tourism products, such as those associated with the names “James Bond”, “Agent 007”, or simply “007”. One example is the transformation of Vila Skyfall in Portugal into a tourism destination after the film was finished shooting. Observing the evolution of film locations into tourism destinations shows that films have a significant impact on the tourism sector. This transformation attests to the influence of the films and their ability to create tourism products that perpetuate the legacy of the saga.

Films transcend the category of entertainment, emerging as a marketing tool for the destinations featured in the films (Vagionis 2011). The strategic creation of tourism products, such as “007”-themed excursions or the marketing of iconic tours, highlights the influence of films on tourist behaviour. This influence goes beyond immediate interest and extends to local economic opportunities. In other words, films captivate global audiences and drive tourism through storytelling (Cardoso et al. 2019), becoming long-lasting tourism opportunities.

In addition, the James Bond character becomes a fictional celebrity who shapes the tourism destination and interest of spectator tourists in visiting film locations. In this way, the image of the character is projected onto the destination and, consequently, onto the tourist. This is the case with products that suggest that tourists “be a Secret Agent” through excursions to certain destinations. Cardoso et al. (2019) highlight structural differences between dream and favourite destinations, which can encourage a tourist to visit a particular destination or not, influenced by the cinema. In this sense, destination marketing can exploit the association between film production and tourism promotion (Kim and Richardson 2003), highlighting that countries with a strong film industry can benefit more from promoting film locations as tourism destinations. Official destination websites linked to film websites also serve as a communication tool for both (Wang and Pizam 2011) in the development of integrated marketing strategies (Hudson and Ritchie 2006; Horrigan 2009). This strategy creates attractive and authentic content on the websites and makes destinations foster partnerships with the film industry (O’Connor et al. 2009; O’Connor 2011). Thus, by applying some of these strategies, destination marketers can harness the potential of film production to boost tourism and increase travellers’ interest in their destinations.

5.3. Countries with the Highest Film Production and Destination Image Promotion Related to James Bond Saga

Turning film locations into tourism destinations is a contemporary phenomenon (Rahman et al. 2019). In fact, the continued demand for tourism products from films highlights the need for long-term marketing strategies and the importance of destinations managing this lasting interest effectively (Almeida and Almeida 2023). The implementation of ongoing marketing strategies is also important in capitalising on the interest generated by cinema, promoting destinations globally in the process. Close collaboration between the film and tourism sectors emerges as a strategy for the economic benefits generated by films in destinations. In addition, these strategies ensure the promotion of destinations, creating a virtuous cycle. The role of films in promoting destinations covers various aspects, such as: attractiveness, lifestyle, travel decisions, products, and tourism marketing. In this sense, films can increase the attractiveness of a destination, such as the Faroe Islands. It is a form of representation of the destination through the cinema and story of the film’s protagonist that arouses interest in visiting these places, becoming spectator tourists.

The James Bond saga often portrays a sophisticated and mysterious lifestyle. Destinations that are the setting for the saga can benefit from being associated with this lifestyle, attracting tourists looking for these experiences. So, if a destination is presented positively in the films, this can motivate people to include it in their travel plans. This is what occurs with the setting of Venice, Italy, which recurs in the 007 films. Because the saga has lasted 60 years, it is common for James Bond to have several fan bases on a global scale. These bases are also co-responsible for the long-lasting “007” effect on fans since 1962. The tourist products generated during and after filming also contribute to attracting visitors.

Destination marketing teams often capitalise on films by developing specific promotional campaigns, partnerships, or events to boost tourism, such as the “Bond is GREAT Britain” campaign. The whole repercussion of recording a film, especially on a global scale, involves creating an exciting image that encourages people to choose these destinations on their next trips.

However, it cannot be said that the James Bond effect applies to every film. The impact on tourism promotion can vary between different films, depending on several factors, such as: popularity, fan base, the way the destination is re-treated, the context of the plot, and the effectiveness of marketing strategies. Thus, some films can have a more significant impact on tourism promotion than others. Films that highlight destinations positively and are associated with engaging narratives are more likely to influence travel decisions. Moreover, marketing strategies adopted by destinations in collaboration with films also play an important role in boosting local and international tourism.

It is more than evident that the tourism sector has been relying on the audio-visual and non-cinematic sector in recent years, especially since the 2000s, making use of it as a promotional tool to complement tourism destinations. Both nationally and internationally, there are numerous examples of films or other audio-visual formats (miniseries or series) with notable recognition among viewers (Game of Thrones, the Harry Potter saga, The Lord of the Rings, etc.). Added to this is their increasingly marked presence in the online world, whether it be in websites, blogs, social networks, or forums, tools that viewers use to share opinions and find out more about their favourite films and series (Riley et al. 1998; Araújo Vila et al. 2021). Thus, it is notable that films play a role in tourists’ decision making and the products that they generate. Destinations portrayed in a positive and exciting way are more likely to be included in viewers’ travel plans. Destinations portrayed in a negative light, on the other hand, can dissuade potential visitors. The interaction between film narrative and destination choice highlights the power of films, not just as entertainment, but as drivers of tourism.

The link between the films and the destinations is also evident on the official websites, where even minimal information about the films is provided to those interested in finding out more about the film sets. From stunning images to detailed descriptions of the landscapes and local attractions, the official websites act as a platform to promote both the films and the associated tourist destinations. It is a strategy that increases the visibility of the destinations and strengthens the association between the films and the real places where they were filmed. The transformation of filming locations into destinations, such as the Skyfall Village in Portugal, the Piz Gloria Restaurant and the dishes served related to the film, and the interactive maps of Scotland, illustrate the impact of the saga films on the development of tourism products. The strategic creation of themed products, such as “007” excursions and tours, highlights the influence of films on tourist behaviour, generating local economic opportunities. In fact, the James Bond character becomes a fictional celebrity who shapes the tourist destination, influencing the interest of spectator tourists in visiting film locations.

Collaboration between the film and tourism sectors can optimise the economic benefits generated by films, creating a mutual relationship that boosts local and international tourism. In addition, the tourism promotion of destinations benefits the local economy and strengthens the image of the destination, generating economic growth. The films have also gained notoriety over the years, in line with the 60th anniversary of the James Bond saga. However, the impact of tourism promotion related to the saga can vary between different destinations and factors.

6. Conclusions

Film-induced tourism as a tourism product, from the tourist’s point of view, consists of travelling to experience a destination seen in a film. On the part of destination managers, it goes beyond the interest of viewers and includes intentional promotion, the induction of the destination image by taking advantage of the popularity of films. This action underlines the proactive involvement of destination stakeholders in using cinematic appeal to boost tourism, essentially reflecting a promotional influence on tourist behaviour. The websites of official promotional organisations, because they reflect the type of tourism products that identify a country/destination, are by nature one of the most image-inducing media.

The James Bond saga, whose first film was released during the Second World War, due to its repercussions and notoriety, fulfils the requirements for studying the projected image of a tourism destination, i.e., promotion. The first two objectives of this work consisted of identifying the promotional image of the James Bond saga on the official websites of the countries where the saga films were shot. Out of the 37 countries and 77 destinations where the James Bond saga was filmed, this study found that only 26% of tourist destinations incorporated the name of James Bond or related elements from the films on their websites to promote and evoke the image of a tourism destination. However, in identifying the countries with the highest film production in the James Bond saga, the interconnection between the film locations and the global exposure of the destinations stands out. As a result, viewers are encouraged to explore these destinations in person, creating a virtuous cycle of tourism promotion. It is notable that among the countries analysed that have produced more than two films, only a few of them stand out in terms of content exposure of film-induced tourism related to the James Bond saga on their tourism promotion websites: the United Kingdom, Scotland, France, and Switzerland. These countries not only incorporate elements from the saga in their promotion but also offer tourism products such as tourist maps of filming locations, gastronomy inspired by the films, and the Schilthorn Piz Gloria restaurant in Switzerland, which serves as a significant tourism attraction. The official tourism websites communicate words that promote the destination’s image, showing a clear link with film-induced tourism products. Among these, the most notable links are found in terms such as “ticket”, “filmed”, and “famous locations”. However, given the potential of film-induced tourism for a tourism destination, it is puzzling why so few countries leverage the James Bond saga as a means to enhance their destination image.

Examining the conversion of the filming locations into tourism destinations, it is evident that there is ample opportunity to utilise the saga films to reshape the destination’s image and enhance film-induced tourism. However, we emphasise the necessity of continuous marketing efforts to capitalise on sustained interest. This study does not make it possible to identify whether or not there have been continuous promotional strategies over time, so future research could explore this detail. Additionally, it would be useful to explore whether there has been any influence on the destination’s image during each film’s debut, aiming to comprehend its effect on viewers’ intentions to travel.

Regarding tourism products related to the saga, this research concludes that the James Bond films serve as both entertainment and tourism marketing tools. In this regard, the projection of the character’s image onto the destination, as suggested by tourism products that invite tourists to “be a Secret Agent”, also demonstrates the power of cinema in shaping travel decisions.

Limitations and Theoretical and Practical Implications

The exploratory phase of this case study identifies all tourist destinations in the James Bond saga and is a useful tool for future research into the subject. The methodology adopted, triangulating the case study with content analysis, is a further contribution to the research area of film-induced tourism.

For researchers in the field of film-induced tourism, this study provides an analysis of a film saga in 60 countries around the world, analysing the image of destinations and the products created from the saga’s films.

Although destination planners have limited control over the content of the films produced in their respective destinations and the way in which the destinations are being portrayed in the films, this study reflects on the image induction that the cases discussed project, allowing destination managers to adopt promotional strategies based on the films.

For managers of tourism destinations that have the potential for film tourism, this work provides insights into how to manage the websites of their destinations to position their projected image and encourage the creation of film-related tourism products. It should also be noted that the emerging markets for this tourism product require new marketing techniques and strategies, especially in the aftermath of COVID-19 and the wars facing the world. The results of this study can be useful for destination managers in planning an effective destination image strategy, allowing them to align the image that films have of the destination with the desired image and potential audience reach.

In terms of economic and social implications, we highlight the impact on the local economy that the transformation of filming locations into tourism destinations can have, generating jobs and increasing revenue through tourism. This highlights the importance of film tourism as a catalyst for economic development in local communities.

The main limitation of this study is that the analysis was limited to the websites of official tourism organisations. Future lines of research could extend the analysis to destination tourism associations and regional promotion websites, among others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.A.-V., L.C., and G.G.F.A.; methodology, L.C.; software, L.C.; validation, N.A.-V., L.C., G.G.F.A., and P.A.; formal analysis, N.A.-V., L.C., and G.G.F.A.; investigation, N.A.-V., L.C., and G.G.F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.-V., L.C., G.G.F.A., and P.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A.-V., L.C., G.G.F.A., and P.A.; visualisation, N.A.-V., L.C., G.G.F.A., and P.A.; supervision, N.A.-V. and L.C.; project administration, N.A.-V. and L.C.; funding acquisition, L.C., G.G.F.A., and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by national funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04470/2020) (accessed on 30 March 2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, Yazeed, and Şafak Ünüvar. 2022. Film tourism and its impact on tourism destination image. Çatalhöyük Uluslararası Turizm ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 8: 102–17. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Giovana Goretti Feijó, and Paulo J. S. Almeida. 2023. The influence of destination image within the territorial brand on regional development. Cogent Social Sciences 9: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Vila, Noelia, José Antonio Fraiz Brea, and Pablo de Carlos. 2021. Film tourism in Spain: Destination awareness and visit motivation as determinants to visit places seen in TV series. European Research on Management and Business Economics 27: 100135. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, Seihmus, and Ken W. McCleary. 1999. A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research 26: 868–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, D. Yu, and N. Shumeiko. 1977. On an exact calculation of the lowest-order electromagnetic correction to the point particle elastic scattering. Nuclear Physics 127: 242–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, Sue. 2005. Film-Induced Tourism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Beeton, Sue. 2006. Understanding film-induced tourism. Tourism Analysis 11: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, Sue. 2009. Why Film? Why Now? Tourism Australia’s Changing Perspectives: A Case Study of Australian Film-induced Tourism. In CAUTHE 2009: See Change: Tourism & Hospitality in a Dynamic World. Fremantle: Curtin University of Technology,, pp. 766–79. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, Bernard. 1982. Content Analysis in Communication Research. Glencoe: Free Press, p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jeremy. 2000. The Politics of James Bond: From Fleming’s Novels to the Big Screen. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolan, Peter, and Kelly Davidson. 2005. Film Induced Tourism in Ireland: Exploring the Potential. Ireland: Ulster University Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, Anne, Kevin Moore, and David Fisher. 2010. Experiencing film tourism: Authenticity & fellowship. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 229–48. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, Dimitrios. 2000. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management 21: 97–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, Graham, and Julia Klug. 2001. Movie-induced tourism: The challenge of measurement and other issues. Journal of Vacation Marketing 7: 316–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Richard W. 1990. The influence of the media in shaping international tourist patterns. Tourism Recreation Research 15: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Martin. 1995. GoldenEye. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Martin. 2006. Casino Royale. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Lucília, Cristina Estevão, Cristina Fernandes, and Helena Alves. 2017. Film-induced tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Studies 13: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Lucília, Francisco Dias, Arthur Araújo, and Maria Isabel Marques. 2019. A destination imagery processing mode: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Annals of Tourism Research 74: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, Márcio Marreiro, and Andréa V. S. Dantas. 2009. The image of Brazil as tourism destination on the european tour operators’ websites. Revista Acadêmica Observatório de Inovação do Turismo 4: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, James. 2024. Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ching Fu, and DungChung Tsai. 2007. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management 28: 1115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, Marie-Hélène, and Chloé Huvet. 2018. From James Bond with love: Tourism and tourists in the Bond saga. Via Tourism Review 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Christina Geng-Qing, and Hailin Qu. 2008. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management 29: 624–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Joanne. 2005. Toddlers, tourism and Tobermory: Destination marketing issues and television-induced tourism. Tourism Management 26: 763–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Joanne. 2012. Film tourism–Evolution, progress and prospects. Tourism Management 33: 1007–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, W. Glen. 2010. Planning for film tourism: Active destination image management. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development 7: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Croy, W. Glen. 2011. Film tourism: Sustained economic contributions to destinations. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 3: 159–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, W. Glen, and Reid D. Walker. 2003. Rural tourism and film-issues for strategic regional development. In New Directions in Rural Tourism. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, pp. 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Francisco, and Lucília Cardoso. 2017. How can brand equity for tourism destinations be used to preview tourists’ destination choice? An overview from the top of Tower of Babel. Tourism Management Studies 13: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Louise E., Tom Griffin, Christopher Gibbs, and Daniel Guttentag. 2021. The impact of video games on destination image. Current Issues in Tourism 24: 554–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Archi, Youssef, and Brahim Benbba. 2023. The Applications of Technology Acceptance Models in Tourism and Hospitality Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 14: 379–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Archi, Youssef, and Brahim Benbba. 2024. New Frontiers in Tourism and Hospitality Research: An Exploration of Current Trends and Future Opportunities. In Sustainable Approaches and Business Challenges in Times of Crisis. Edited by Adina Letiția Negrușa and Monica Maria Coroş; ICMTBHT 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksson, Jonnie, and Kalle Jonasson. 2023. “I’m not a sporting man, Fräulein”: The Tragedy and Farce of James Bond’s Heroic Prowess. International Journal of James Bond Studies 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, S. 2013. Destination image on the web: Evaluation of pernambuco’s official tourism destination websites. Business Management Dynamics 2: 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Matthew, and Ajay Chowdhury. 2015. Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films. Cheltenham: The History Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Marc. 2008. Quantum of Solace. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Freire-Medeiros, Bianca, Fernanda Nunes, and Lívia Campello. 2011. Sobre afetos e fotos: Volunturistas em uma favela carioca. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga, C. Joji. 2020. No Time to Die. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, William. 1994. Image Formation Process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2: 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Lewis. 1967. You Only Live Twice. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Lewis. 1979. Moonraker. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldi, Angeli, and Ludovica Cesario. 2017. Film marketing opportunities for the well-known tourist destination. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 13: 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, John. 1983a. Licence to Kill. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Glen, John. 1983b. Octopussy. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Glen, John. 1987. His Name is Danger. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, Robert, and Frank M. Go. 2004. Projected destination image online: Website content analysis of pictures and text. Information Technology & Tourism 7: 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, Ulrike, Juyeon Ham, and Chulmo Koon. 2018. Creating the city destination of the future: The case of smart Seoul. Managing Asian Destinations 2018: 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Guy. 1971. Diamonds for Eternity. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Guy. 1974. The Man with the Golden Gun. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Hochscherf, Tobias. 2013. Bond for the Age of Global Crises: 007 in the Daniel Craig Era. Journal of British Cinema and Television 10: 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsti, Ole R. 1969. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan, David. 2009. Branded content: A new model for driving Tourism via film and branding strategies. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism 4: 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Simon, and J. R. Brent Ritchie. 2006. Promoting destinations via film tourism: An empirical identification of supporting marketing initiatives. Journal of Travel Research 44: 387–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Simon, Youcheng Wang, and Sergio Moreno Gil. 2011. The influence of a film on destination image and the desire to travel: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Tourism Research 13: 177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Peter R. 1969. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, William C. 2016. The social construction of tourism online destination image: A comparative semiotic analysis of the visual representation of Seoul. Tourism Management 54: 221–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiassen, Alexander, A. George Assaf, Linda Woo, and Florian Kock. 2016. The imagery-image duality model: An integrative review and advocating for improved delimitation of concepts. Journal of Travel Research 55: 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičić, Dobrica. 2019. From the traditional understanding of tourism destination to the smart tourism destination. Current Issues in Tourism 22: 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juškelytė, Donata. 2016. Film Induced Tourism: Destination Image Formation and Development. Regional Formation and Development Studies 19: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaikati, Andrew M., and Jack G. Kaikati. 2004. Stealth marketing: How to reach consumers surreptitiously. California Management Review 46: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershner, Irvin. 1983. Never Say Never Again. [Film]. Paris: Independent Production. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyangmi, and Sarah L. Richardson. 2003. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Annals of Tourism Research 30: 216–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sangkyum. 2012. Audience involvement and film tourism experiences: Emotional places, emotional experiences. Tourism Management 33: 387–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sangkyum, and Hua Wang. 2012. From television to the film set: Korean drama Daejanggeum drives Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese and Thai audiences to screen-tourism. International Communication Gazette 74: 423–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sun Eung, Soo Il Shin, and Sung-Byung Yang. 2017. Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Information & Management 54: 687–702. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1990. Metodología de análisis de contenido: Teoría y práctica. Piados Comunicación 1: 269–79. [Google Scholar]

- Laba, Nengah. 2018. A content analysis of media information exposure on tourism destination image. Journal of Business on Hospitality and Tourism 4: 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Yong, Zeya He, Yunpeng Li, Tao Huang, and Zuyao Liu. 2023. Keep it real: Assessing destination image congruence and its impact on tourist experience evaluations. Tourism Management 97: 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, Cristoph. 2009. The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Mancheste: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Young, Wei Lee Chin, Florin Nechita, and Adina Nicoleta Candrea. 2020. Framing film-induced tourism into a sustainable perspective from Romania, Indonesia and Malaysia. Sustainability 12: 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luštický, Martin, Jirí Dvorák, and Petr Stumpf. 2020. The cultural content analysis of the international tourism destination websites. Trendy v Podnikání 10: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macionis, Nicole. 2008. Film-Induced Tourism: The Role of Film as a Contributor to the Motivation to Travel to a Destination. Nathan: Griffith University. [Google Scholar]

- Macionis, Niki, and Beberly Sparks. 2009. Film-induced tourism: An incidental experience. Tourism Review International 13: 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, Ana, and Rui Costa. 2018. Imagem projetada de Portugal como destino turístico: Análise qualitativa do portal oficial de promoção turística. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento (RT&D)/Journal of Tourism & Development 29: 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- McInerney, J. 1996. James Bond 007 from Goldinger to Goldeneye. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, Ana Cristina. 2016. Salman Rushdie in the Cultural Marketplace. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, Sam. 2012. Skyfall. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, Sam. 2015. Spectre. [Film]. London: EON Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulou, Eleni, Alexandra Siurnicka, and Delia Moisa. 2022. Experiencing the story: The role of destination image in film-induced tourism. In Global Perspectives on Literary Tourism and Film-Induced Tourism. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 240–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Sánchez, Isabel, Francesc Font-Clos, and Álvaro Corral. 2016. Large-scale analysis of Zipf’s law in English texts. PLoS ONE 11: e0147073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Nigel, and Annette Pritchard. 1998. Tourism Promotion and Power: Creating Images, Creating Identities. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Morrand, Jean-Claude, Lucília Cardoso, Alexandra Pereira, Noelia Araújo-Vila, and Giovana Almeida. 2021. Tourism ambassadors as special destination image inducers. Enlightening Tourism. A Pathmaking Journal 11: 194–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Peter, Mark Pritchard, and Brock Smith. 2000. The destination product and its impact on traveller perceptions. Tourism Management 21: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]