Whistleblowing Based on the Three Lines Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definition of Whistleblowing and Whistleblowing Framework

2.1. Internal and External Whistleblowers

2.2. Whistleblower versus Whistleblowing

2.3. Emphasis on Internal Audit and Fraud Examination

2.4. Definition of “Reasonable Suspicions”

2.5. Definition and Application of the “Impartiality” Imperative

3. The IIA’s Three Lines Model and Its Application to a Whistleblowing Framework

3.1. Governing Body

3.2. First-Line Roles

3.3. Second-Line Roles

3.4. Third Line

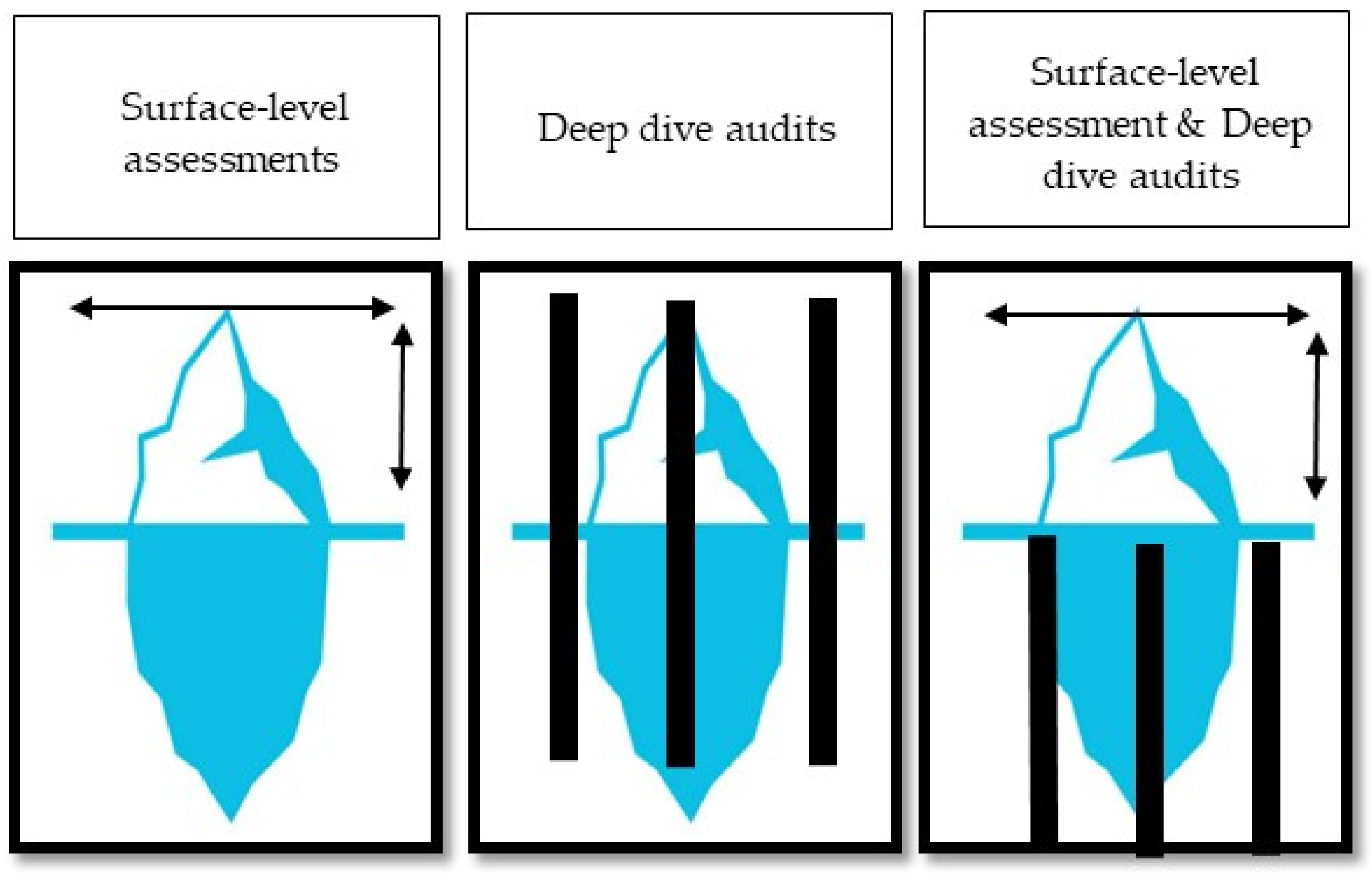

- ■

- surface-level whistleblowing assessment,

- ■

- deep-dive whistleblowing audits, or

- ■

- surface-level and deep-dive whistleblowing audits.

- Method 1: surface-level assessment

- Method 2: deep-dive assessment

- Method 3: surface-level assessment and deep-dive assessment

3.5. Transnational Aspects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Impartiality The need for impartial investigations is highlighted by (ISO 37002:2021) and researchers (Kagias et al. 2023). |

| 2 | Ultimate responsibility Although Directive 1937/2019 does not provide any guidance in respect of ultimate responsibility, professional bodies, standard-setting bodies, and researchers (PCBS 2013; Public Concern at Work 2013; CIIA 2014; Greene and Latting 2004; Kagias et al. 2023) suggest that it should be assigned to independent non-executive directors, or committees consisting of non-executive directors. |

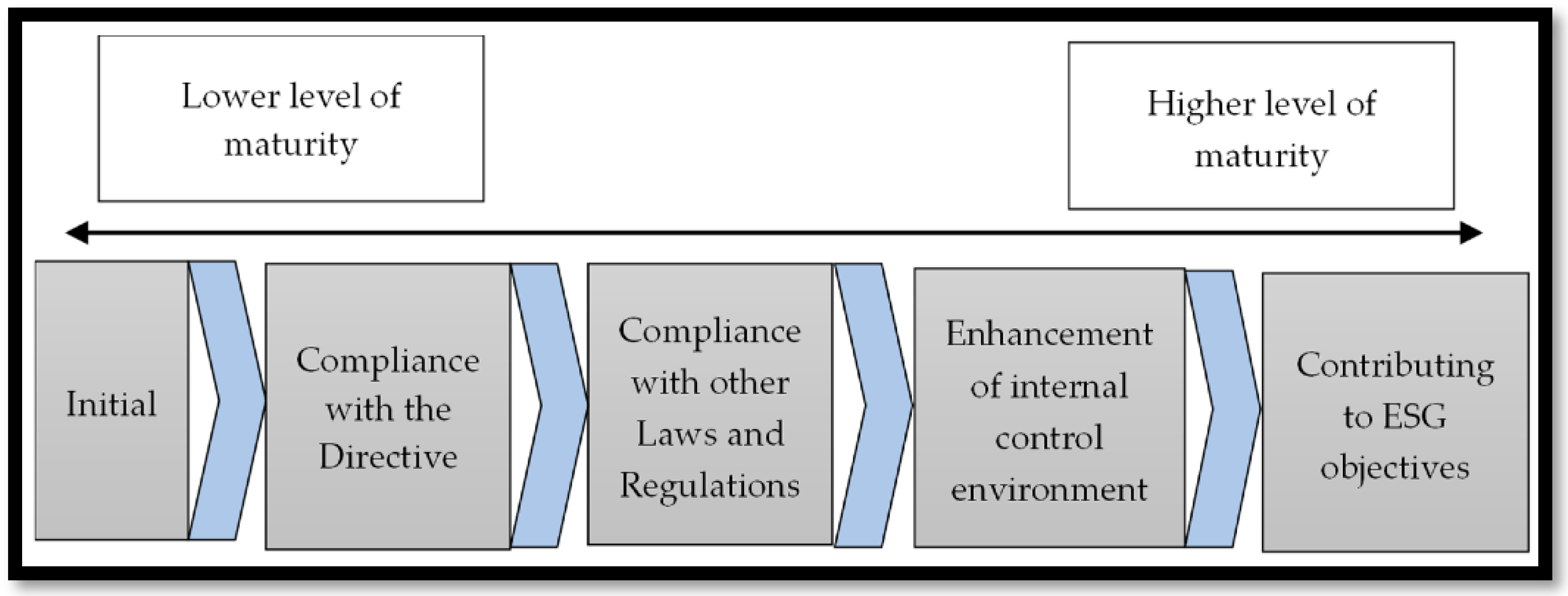

| 3 | Level of maturity The maturity model provided by (Kagias et al. 2023) may be used to establish objective criteria. |

| 4 | Reporting: The (GRI 2016) suggests certain disclosures in the annual reports or elsewhere. |

| 5 | Framework and strategies for facilitating employee whistleblowing. The framework provided by (Berry 2004) could be used. |

| 6 | Outsourcing activities Both the International Standards for the Professional Practice for Internal Auditing and the International Standards on audit recognize the risks associated with the outsourcing of activities. The IIA has issued recommended guidance (IIA 2018). |

References

- Alford, C. Fred. 2002. Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2022a. Manual. Available online: www.acfe.com/-/media/images/acfe/products/publication/fraud-examiners-manual/2022_fem_sample_chapter.ashx#:~:text=Act%20on%20Predication,-Fraud%20examinations%20must&text=In%20other%20words%2C%20predication%20is,each%20step%20in%20an%20examination (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2022b. Occupational Fraud 2022. A Report to the Nations. Available online: https://legacy.acfe.com/report-to-the-nations/2022 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA). 2019. Internal Audit’s Role in Whistleblowing. Available online: www.accaglobal.com/gb/en/member/discover/cpd-articles/governance-risk-control/ias-role-in-whistleblowing.html#:~:text=Internal%20Audit’s%20assurance%20role%20includes,Review%20the%20whistleblowing%20policy (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Ayers, Susan, and Steven E. Kaplan. 2005. Wrongdoing by consultants: An examination of employees’ reporting intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 57: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Benisa. 2004. Organizational culture: A framework and strategies for facilitating employee whistleblowing. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 16: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, Glen, Peter J. Baldacchino, Sandra Buttigieg, Engin Boztepe, and Simon Grima. 2020. Challenging the adequacy of the Conventional ‘Three lines of Defence’ model: A case Study on Maltese Credit Institutions. In Contemporary Issues in Audit Management and Forensic Accounting. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 102, pp. 303–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brenninkmeijer, Alex, Gaston Moonen, Raphael Debets, and Branislav Hock. 2018. Auditing standards and the accountability of the European Court of Auditors (ECA). Utrecht Law Review 14: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors (CIIA). 2014. Whistleblowing and Corporate Governance. In The Role of Internal Audit in Whistleblowing. London: Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors. [Google Scholar]

- Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors (CIIA). 2023. Position Paper: Internal Audit and Whistleblowing. Available online: www.iia.org.uk/resources/ethics-values-and-culture/whistleblowing/position-paper-internal-audit-and-whistleblowing/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Culiberg, Barbara, and Katarina Katja Mihelič. 2017. The evolution of whistleblowing studies: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics 146: 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 1937/2019, on the Protection of Persons Who Report Breaches of Union Law. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L1937 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Dworkin, Terry Morehead, and Melissa S. Baucus. 1998. Internal vs. external whistleblowers: A comparison of whistleblowering processes. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 1281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Scott, Jonathan Marks, and Richard Riley. 2018. Meta-model of fraud. Fraud Magazine, July/August. pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). 2016. GRI 102: General Disclosures 2016. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Annette D., and Jean Kantambu Latting. 2004. Whistleblowing as a form of advocacy: Guidelines for the practitioner and organization. Social Work 49: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hakim, Andi Lukman. 2017. Application of Three Lines of Defence in Islamic Financial Institution in Malaysia. International Journal of Management and Applied Research 4: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Henik, Erika. 2015. Understanding whistle-blowing: A set-theoretic approach. Journal of Business Research 68: 442–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigoyen, Marie-France. 2004. Stalking the Soul. New York: Helen Marx Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, Branislav, and Elizabeth Dávid-Barrett. 2022. The compliance game: Legal endogeneity in anti-bribery settlement negotiations. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 71: 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Academy of Management Review 9: 389–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS Foundation. 2018. Conceptual Framework. London: IFRS Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). 2022. ISO 37002. Whistleblowing Management Systems—Guidelines. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65035.html (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Jubb, Peter B. 1999. Whistleblowing: A restrictive definition and interpretation. Journal of Business Ethics 21: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagias, Paschalis, Nikolaos Sariannidis, Alexandros Garefalakis, Ioannis Passas, and Panagiotis Kyriakogkonas. 2023. Validating the Whistleblowing Maturity Model Using the Delphi Method. Administrative Sciences 13: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpacheva, Elina, and Branislav Hock. 2024. Foreign whistleblowing: The impact of US extraterritorial enforcement on anti-corruption laws in Europe. Journal of Financial Crime 31: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, John P. 2007. Comparing Chinese and American managers on whistleblowing. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 19: 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luburić, Radoica. 2017. Strengthening the three lines of defense in terms of more efficient operational risk management in central banks. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice 6: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luburić, Radoica, Milan Perovic, and Rajko Sekulovic. 2015. Quality management in terms of strengthening the “three lines of defence” in risk management-process approach. International Journal for Quality Research 9: 243. [Google Scholar]

- Minto, Andrea, and Isabella Arndorfer. 2015. The “Four Lines of Defence Model” for Financial Institutions. Taking the Three-Lines-of-Defence Model Further to Reflect Specific Governance Features of Regulated Financial Institutions. BIS Papers. Basel: BIS, vol. 11, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Near, Janet P., and Marcia P. Miceli. 1985. Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS). 2013. Available online: www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/banking-commission/Banking-final-report-volume-i.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Public Concern at Work. 2013. Report on the Effectiveness of Existing Arrangements for Workplace Whistleblowing in the UK. London: Public Concern at Work. [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankar, Lilanthi. 2003. Encouraging Internal Whistleblowing in Organizations. Available online: www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/submitted/whistleblowing.html (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). 2023. SEC Awards More than $28 Million to Seven Whistleblowers. Available online: www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-257#:~:text=Whistleblower%20awards%20can%20range%20from,could%20reveal%20a%20whistleblower’s%20identity (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Tammenga, Alette. 2020. The application of Artificial Intelligence in banks in the context of the three lines of defence model. Maandblad voor Accountancy en Bedrijfseconomie 94: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, A. Assad, John P. Keenan, and Biljana Cranjak-Karanovic. 2003. Culture and whistleblowing an empirical study of Croatian and United States managers utilizing Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics 43: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2013. The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control. Position Paper. Available online: https://www.iia.org.uk/policy-and-research/position-papers/the-three-lines-of-defence/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2018. Auditing Third-Party Risk Management. Lake Mary: IIA. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2019. Fraud and Internal Audit. Assurance over Fraud Controls Fundamental to Success. Lake Mary: IIA. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2020. The IIA’s Three Lines Model. Lake Mary: IIA. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). 2024. Definition of Internal Auditing. Available online: www.theiia.org/en/standards/what-are-the-standards/definition-of-internal-audit/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), and Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). 2022. Building a Best-in-Class Whistleblower Hotline Program. Lake Mary: IIA. Austin: ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), and WBCSD. 2022. Embedding ESG and Sustainability Considerations into the Three Lines Model. Lake Mary: IIA. Geneva: WBCSD. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute of Internal Auditors Australia (IIAA). 2021. Auditing Risk Culture: Practical Guide. Sydney: IIA-Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Trasparency International Netherlands (TI-NL). 2019. Whistleblowing Frameworks 2019 Assessing Companies in Trade, Industry, Finance and Energy in The Netherlands. Amsterdam: Trasparency International Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- US Accountability Project. 2015. A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office.

- Vousinas, Georgios L. 2021. Beyond the three lines of defense: The five lines of defense model for financial institutions. ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives 10: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Jinyun, Stuart Thomas, and Diane L. Miller. 2005. Examining culture’s effect on whistle-blowing and peer reporting. Business & Society 44: 462–86. [Google Scholar]

| Inbound Information | Outbound Information | |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | If it provides a reasonable basis to initiate an investigation | If it uncovers malpractice and/or confirms or alters the understanding of the organization on risks and controls. |

| Timeliness | If it is provided within a time frame that makes it actionable. | If it is investigated within the period provided by the law. |

| Faithfull representation | Complete, neutral, and free from misrepresentations | Impartial and based on factual evidence |

| Verifiability | If a competent third party would reach the same conclusions. | |

Whistleblowing is the disclosure of real, suspected, or anticipated cases of actionable information. Information is actionable if it is relevant and faithful.

|

| An internal whistleblowing framework is the totality of formal and informal practices which proactively encourage reporting of actionable information and safeguard impartial1 investigations and the governance mechanisms that define roles and responsibilities, allowing the Organization to enhance risk management (including fraud risks) and strengthen the overall internal control environment. |

| IIA’s Three Lines Model | Application to Whistleblowing Framework | |

| The Governing Body | Accepts accountability to stakeholders for oversight of the organization |

|

| Engages with stakeholders to monitor their interests and communicate transparently on the achievement of objectives |

| |

| Nurtures a culture promoting ethical behavior and accountability |

| |

| Establishes structures and processes for governance, including auxiliary committees as required |

| |

| Delegates responsibility and provides resources to management to achieve the objectives of the organization |

| |

| Determines organizational appetite for risk and exercises oversight of risk management |

| |

| Maintains oversight of compliance with legal, regulatory, and ethical expectations |

| |

| Establishes and oversees an independent, objective, and competent internal audit function |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kagias, P.; Garefalakis, A.; Passas, I.; Kyriakogkonas, P.; Sariannidis, N. Whistleblowing Based on the Three Lines Model. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14050083

Kagias P, Garefalakis A, Passas I, Kyriakogkonas P, Sariannidis N. Whistleblowing Based on the Three Lines Model. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(5):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14050083

Chicago/Turabian StyleKagias, Paschalis, Alexandros Garefalakis, Ioannis Passas, Panagiotis Kyriakogkonas, and Nikolaos Sariannidis. 2024. "Whistleblowing Based on the Three Lines Model" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 5: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14050083

APA StyleKagias, P., Garefalakis, A., Passas, I., Kyriakogkonas, P., & Sariannidis, N. (2024). Whistleblowing Based on the Three Lines Model. Administrative Sciences, 14(5), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14050083