Abstract

Working in the digital age requires a discussion on the right to disconnect. Although it has previously been studied in association with the digital transition movement, the “right to disconnect” has gained relevance in a context of mandatory teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This situation has led some countries to legislate on the subject, notably Portugal, where the right to disconnect has been enshrined in labour legislation since law no. 83/2021 of 6 December. This article presents a framework of the literature on the right to disconnect, as well as a documentary analysis and an exploratory study carried out in Portugal in November and December 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey sought to assess the working conditions of women in telework, particularly about working time. This study stresses that the right to disconnect is linked to the organisation of working time and analyses the negative impact of technology on work, in particular the permanence of the electronic connection to work. The results show that the majority of women value teleworking because they have more time for themselves and their families. However, the women who consider that they have less availability for teleworking indicate that the main reason for this is not being able to disconnect from work. In the context of the digital transition and the expansion of teleworking in organisations and the generalisation of hybrid work, the study of this new “right to disconnect” becomes crucial.

1. Introduction

In a context of mandatory teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the expansion of this type of work, reflection on the ‘right to disconnect’ associated with teleworking has gained greater relevance. And today, with the permanence of hybrid work (a mix of face to face and teleworking), this relevance continues. Telework emerged in the late 1970s (Nilles 1988), associated with technological progress and the traditional way of working at home that facilitated the multiplication of experiences of work relocation. Telework, or telecommuting, was then defined as a work practise that uses technology to interact with other people and perform work tasks (Allen et al. 2015, p. 44) and that allows working remotely through information and communication technologies (ICTs) (Eurofound 2010; Greer and Payne 2014). Since then its use has gradually expanded (Lister and Harnish 2011, 2019; Tugend et al. 2014; Gallup 2017; European Commission 2020).

In the 1980s, the strong impact of ICT on employment enabled large companies to develop an activity that transcended state borders (Crompton et al. 1996, pp. 5–6). In addition, the increasing use of these technologies has had implications for individuals and families as well as organisations (Eurofound 2009; Kossek and Lautsch 2012; European Commission 2015). Consequently, most employers are increasingly responding to the pressure to create a family-friendly workplace and a work–life balance (Gershuny 2000; Eurofound 2006; OECD 2013, 2016). Some studies underline that discussions of technological change tend to focus mainly on its impact on the labour process as well as on employment levels in general, in particular on the restructuring of old occupations and skills (Crompton et al. 1996, p. 2). Teleworking is above all a form of organisational development (Peiperl and Baruch 1997). As a form of work largely supported by new technologies, with telework, new productive and social demands have been created. It is therefore important, firstly, to clarify that—as a way of organising work—telework is viable both in a subordinate employment relationship and in an independent work relationship. Secondly, it is necessary to consider that telework can satisfy new needs of companies, particularly in situations where it is applied in a mixed form, partially or alternately with face-to-face work. Thirdly, teleworking must also be understood in relation to business strategies, both national and international, by seeking to develop forms of networked communication between companies, which can integrate work at home.

The literature highlights the notion of telework as a ‘virtual place’ that is also a form of an electronic-mediated (dis)incorporation of simultaneous individual and/or group positions, with consequences for the organisation of work (Leeds and Leeds 2003; Golden and Raghuram 2010; Degryse 2016). In this context, telework presents several advantages, both for employees and employers and society in general (ILO 2020a, 2020c). Companies seek to reduce the surface area of their workplaces and thus make their activity more profitable. In terms of disadvantages for companies, teleworking implies a profound change in behaviour. In the first place, one can speak of weakening the management power of employers, since it diminishes regular contact with employees and, consequently, direct control over them. It should also be noted that for employers—sceptical about work processes that are difficult to supervise—telework can be perceived as a form of work granted only for some workers benefiting from such a right (Eurofound and ILO 2017; Lott and Abendroth 2019).

Teleworkers, on the other hand, sometimes tend to gain autonomy, higher productivity, better work–life balance, and greater well-being. However, there are also disadvantages, as teleworking can lead to longer working hours. The mainstream literature has long emphasised the positive impact of teleworking on reconciling family life (Duxbury et al. 1998; Shojanoori et al. 2015).

However, there are also disadvantages, as teleworking can lead to longer working hours, overlapping of work and home life, and higher work intensity. Several studies show that the use of ICTs in work tends to lead to higher levels of work intensity (Askenazy 2004; Derks and Bakker 2010; Kelliher and Anderson 2010; Grant et al. 2013; Piasna 2018, 2020; Menon et al. 2020; Eurofound 2020c). Kelliher and Anderson (2010) analyse the topics of high job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and work intensification. As these authors point out, remote workers may find themselves working harder in order to meet the expectations of their co-workers (Kelliher and Anderson 2010, p. 87). Based on the studies of Molm et al. (1999), these authors support the thesis of reciprocal exchange, whereby employees tend to intensify their work because they think they benefit from the remote activity. Felstead and Henseke (2017) sought to identify factors explaining the increase in remote working. As these authors emphasise, employers are under pressure to adapt their working practises to the changing demographics of the workforce. Thus, they seek to offer the opportunity to telework to groups such as ‘working parents’, allowing them to reconcile work and family life (Felstead and Henseke 2017). Other studies identify more intense conflicts among teleworkers who have children (Zhang et al. 2020), especially women, who have greater difficulties in reconciling family life (Kurowska 2020). For this author, the impact of teleworking on work–life balance is significant, as companies demand a permanent connection from employees (expecting them to respond to labour issues outside normal working hours) and, as a result, work–family conflict increases, a situation that has worsened during the pandemic. Other authors have observed that strategies to improve connectivity between remote workers, in addition to facilitating communication and collaboration, can strengthen a sense of community and employee engagement (Graham et al. 2023). With the aim of identifying the impact of teleworking on well-being at work—based on the experience of contact centre operators during the COVID-19 pandemic—Santos and Pereira (2023) identify seven dimensions that aggregate the positive impacts associated with teleworking, enhancing well-being and performance. More recently, another study by Tan et al. (2024) used data from 358 married Singaporean women to analyse the effects of teleworking on life satisfaction, mediated by work–life balance, workplace relationships, and working hours. The results suggest a positive association between teleworking and work–life balance as a mediating factor. This study recommends that organisations should consider the potential benefits of teleworking for work–life balance and life satisfaction, while weighing up its drawbacks.

And if with the expansion of ICTs and the use of telework, more and more workers recognise that they remain electronically connected to their work even when they finish their working hours—particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic—there is an alert about the negative impact on workers’ wellbeing of the possible increase in working time (ILO 2020c). Thus, considering the emergence of a new right associated with the digital transition movement and, in particular, teleworking, some governments have found the need to protect workers and integrate by law the right to disconnect.

Especially in the current context of hybrid work, it is therefore important to carry out research that identifies the regulation of the right to disconnect, especially in countries that have a high average number of working hours per week. Hence, it is important to develop research that identifies the need to regulate the right to disconnect, especially in countries that have a high average number of working hours per week. Considering the relationship between the increased use of communication technologies and working time—in particular long hours—lately the literature has assessed the relationship between telework and working time by addressing the issue of the right to disconnect (Pansu 2018; Hesselberth 2018; Avogaro 2018; Eurofound 2020c, 2023a; Jungryeol and Sundong 2020; Miernicka 2024).

Reflection on the right to disconnect has focused in particular on identifying the legal implications of its progressive legalisation (Ray 2016). In 2018, taking the discussion of the ‘right to disconnect’ as a starting point, Hesselberth (2018) emphasises the importance of looking at discourses on dis/connectivity from the point of view of the current ‘culture of connectivity’. As some authors emphasise, disconnection means the right of employees to disconnect from work-related communications during their time off (including holidays). To this end, the employee must also refrain from participating in work activities via ICT during this period (Hopkins 2024). On the other hand, Miernicka (2024) identifies the risks to equality posed by the development of ICT use in professional activity and addresses the right to disconnect associated with the problem of inequalities in teleworking. Other studies (Zlatanović and Škobo 2023) explore the impact of psychosocial risks and challenges in the digital era and discuss whether it is necessary to introduce new rights, particularly the right to disconnect. These authors point out that the right to rest and leisure was created to protect workers and can be analysed in relation to working conditions. And to this extent, they argue that the so-called ‘right to disconnect’ can serve to respond to the problem of psychosocial risks arising from the constant availability of workers in the society of the digital age (idem).

Thus, reconciling work—in particular telework—with family life is a key issue, in an increasingly ageing society, for policy-makers and social partners. Until the beginning of 2020, the legal regime of telework seemed adjusted and in adherence to this form of work provision, but was residual in most countries. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic, it became massive, remaining so to this day, especially in a hybrid labour regime. Hence, ‘the right to disconnect’—in particular associated with the practise of telework—has recently become central to the discussion of each country’s labour problems. For this reason, this is the central theme of this paper.

In the implementation of employment policies, working time regulation has been crucial to improving working conditions and workers’ health and safety (Eurofound 2013, 2015; Campbell and Van Wanrooy 2013; Ganster et al. 2018). How to conciliate professional life with personal and family life is a key concern not only for workers but particularly for policy-makers, social partners, and organisations. At the same time, other factors are transforming the relationship between work and private life, such as technological change and digital work (European Commission 2010, 2020; Eurofound 2018, 2020a, 2020d, 2023b).

Although the specific literature on the right to disconnect is still very scarce, an analysis was made of the literature that relates this topic to the themes of long working hours and work overload: all the more so as the attempt to ensure the right to disconnect aims to guarantee an effective right to rest. Work overload can have effects on workers. Thus, overload usually leads to lower levels of organisational commitment, more absenteeism, negative effects on mental and physical health, and even worse work performance. Overload has also been shown to negatively affect individuals’ role within their families, which can result in increased levels of anxiety, burnout, fatigue, depression, and emotional and physiological stress (Duxbury and Halinski 2014; Berniell and Bientenbeck 2017). Some studies relate working time to theories of stress, either by identifying health problems at work (Li et al. 2007; Rice 2012) or social isolation (Nicholson 2009). Other studies link working time to problems of expectations by studying the ability of workers to ensure performance by adapting their working time management; Reid and Ramarajan (2016) conclude that most men and women—parents and non-parents alike—show a lot of difficulty in focusing only on work, seeking simultaneously to manage other parts of their lives. The authors analyse the combination of three pressure factors on employees: economic incentives, authority figures, and deep psychological needs. And they suggest the way to a healthier and more productive organisational culture through small management changes.

Moreover, company culture can intensify the use of this permanent contact in a more competitive and individualistic working environment. While some employees accept it, motivated by rewards or a strong sense of duty, others accept it out of fear of job insecurity (Burchell 2002; Adascalitei and Heyes 2021). Hence, responding to this problem is particularly important in countries with a high level of job insecurity. Other studies have identified that overwork and the resulting stress can lead to serious health problems, such as sleep problems, depression, or heart disease (Hewlett and Luce 2006; Ganster et al. 2018). They are also terrible for a company’s bottom line, showing up as absenteeism, turnover, and rising health insurance costs. In addition, researchers have found that overwork can impair the performance even of workers who work long hours voluntarily. Exhaustion makes workers more likely to make mistakes when they are tired (Dembe et al. 2005; Dembe 2009).

Regarding long working hours, it is worth noting the importance of its articulation with telework. With the expansion of the use of mobile technologies, the main objective of companies is to seek to increase productivity at work, sometimes leading to an intensification of work. In this context, seeking to balance the demands of work and family life, employees with families struggle daily to cope with these responsibilities. A current question is to confirm whether telework can help employees to achieve this desired reconciliation while ensuring their productivity at work. However, telework may also have disadvantages and involve specific risks, namely regarding the (non)limitation of working time. In effect, telework, if not duly safeguarded, may make the worker not disconnect from work and work more hours than usual, with an increase in stress and other psychosocial risks (Pinsonneault and Boisvert 2001; Eurofound 2017, 2020b).

In a digital transition context in several European countries, this right was already enshrined in their legal systems before the pandemic. However, there is currently no legal framework in the European Union directly regulating the right to disconnect, although the Working Time Directive (Directive 2003/88/EC) does protect a number of rights relating to daily and weekly rest periods and workers’ health and safety. With the increase in teleworking accelerated by the pandemic, concerns about an “always on” culture and the permanent connection of workers have intensified, leading them to work additional and often unpaid hours (Eurofound 2023a). It should also be noted that the European Parliament Resolution in favour of the right to disconnect, of 21 January 2021, invites the European Commission to prepare a directive on this right to disconnect, namely by imposing minimum requirements for remote working, hours, and rest periods.

As mentioned in this section, the literature indicates that telework can intensify work, prolonging the working day. The relevance of this article is therefore to evaluate the working conditions of women who telework, in particular working hours, and assess the relevance of the right to disconnect. The period of the pandemic, with teleworking expanded, was an excellent time to analyse the relationship between working time and teleworking and the relevance of the right to disconnect. So, this study was designed, on the one hand, to understand whether teleworking from home is seen as a benefit for women (and thus a way of promoting gender equality) since it allows them to make their time more flexible in line with their family responsibilities. On the other hand, in a digital society that tends to impose permanent connections, we also sought to identify the importance of this reinforcement of the right to rest and personal and family life, which is the regulation of this new right to disconnect. After analysing the literature on the subject, the next section—Material and Methods—will focus on presenting how this study was developed, based on exploratory research. Section 3 presents the results of this study and Section 4 discusses these results. Finally, Section 5 draws the conclusions and recommendations for future research.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. The Empirical Study—An Exploratory Study in PORTUGAL

As mentioned in the Introduction, this study began with a framing of the topic, through an analysis of the literature both on teleworking and working time, and specifically on the right to disconnect. To reinforce this, it was also decided to carry out a documentary analysis of various reports on the Portuguese labour context in 2020, namely documents from the Portuguese Ministry of Labour, identified here as the MTSSS. This was complemented with a study conducted by Rebelo et al. (2020) that discussed the relationship between teleworking and working time and its impact during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal. This study, conducted in June and July 2020, was based on semi-structured interviews with Portuguese social partners (employer confederations and trade union confederations) and provided an understanding of how they assessed the relationship between telework and working time, in particular with regard to the right to disconnect. The interviewees were confederations, members of the Economic and Social Council (ESC), the main institution for social dialogue in Portugal. And the discussion of the results of this study was important since it preceded the enshrinement in Portuguese law of the right to disconnect.

In this empirical study, the main research questions that guided the investigation were as follows: RQ1—Did women who teleworked during the pandemic feel a lack of time for themselves and their families? RQ2—If so, what are women’s perceptions of their ability to reconcile work with personal and family life when teleworking? RQ3—What is the profile of the women who most claim the right to disconnect (by age, marital status, and number of children)? Departing from these research questions and based on this previous research on working time and telework, a questionnaire was drawn up to collect responses from the largest possible number of women who teleworked in 2020 and 2021, to gather their perceptions about their experiences of teleworking. The sampling plan for this research was drawn up according to its objectives and the characteristics of the target population, such as the availability and accessibility of the people to be surveyed (the survey was made available on social networks). It was considered that non-probability sampling methods are particularly pertinent in research objects where there is no population list of the universe to be surveyed. Therefore, given these constraints inherent to the object of study, the units to be surveyed were selected non-randomly. More specifically, in November 2021, a survey on working time was administered to women with an employment contract (a non-probability sample), seeking to know their opinion and to understand if, during the years 2020 and 2021, they had been able to reconcile professional life with personal and family life, and in particular inquiring about the importance of the right to disconnect. Although this survey had multiple-answer questions, this questionnaire consisted essentially of closed questions to facilitate the analysis of information. It was structured in two parts, the first with a personal and contractual profile—gender, age, marital status, level of education, professional category, employment contract, and seniority—and the other part on working time and working conditions, with a total of 16 questions, some with multiple answers. A total of 155 women with employment contracts—since only in these contracts can the right to disconnect be assessed by reference to the contracted working time—responded to this survey. The statistical analysis was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (IBM Corp 2020), and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages).

2.2. Documentary Analysis on the Right to Disconnect

As the specific literature on the right to disconnect is very scarce, we also carried out an analysis of specific documents relating this topic to the themes of long working hours and work overload.

In Portugal, a study from the Portuguese Ministry of Labour led to the enshrinement of this right in Portuguese labour law. This study emphasised what had been enshrined in France in 2016, as well as mentioning the Belgian law of 2018, the Italian law of 2017 (emphasising that “lavoro agile resembles a tertium genus between face-to-face and remote work”), and the Spanish law of 2018 (MTSSS 2021, pp. 92–93). The right to disconnect was enshrined in law no. 83/2021 of 6 December, amending the Portuguese Labour Code, in the form of a duty to refrain from contact for the employer. This right came into effect in January 2022. Article 199.°-A (entitled ‘Duty to refrain from contact’) has been added to the Portuguese Labour Code, paragraph 1 of which states that, except in cases of force majeure, ‘the employer has a duty to refrain from contacting the worker during his rest period’. It also provides, in paragraph 2, for the protection of employees against any discrimination or less favourable treatment—in particular in regards to working conditions and career progression—as a result of the exercise of this right. This duty on the part of the employer reinforces the employee’s right to disconnect from professional activity in their rest time, refusing, for example, to answer their mobile phone or respond to emails outside of their working hours. Furthermore, special duties for the employer have been established for the teleworking regime in Article 169.°-B(1) of the Labour Code, which lays down the employer’s duty to refrain from contacting the worker during the rest period, under the terms of the aforementioned Article 199.°-A.

Thus, this article explores the potential for understanding the evolving relationship between telework and working time and the importance that the right to disconnect will assume for labour regulations (either legally or by conventional means).

In this respect, it should be noted that a report by Eurofound and ILO (2017) highlights that the increasing use of teleworking has been driven by the demand from companies for better performance and productivity and that it is linked to the demand for more efficient and time-saving work processes (due to reduced commuting times). Moreover, as this report suggests, the growth of telework was also driven by the development of new business models, such as digital platforms, as well as by the desire to help workers reconcile work with family and personal life. As another report states, in the past decade, at least in some countries, such as Portugal, the overwork model has been consolidated (ILO 2018). Employers expect employees to work to be available outside working hours (in their rest time) and to do so voluntarily. In countries with higher levels of precariousness, employees tend to give up their rest time to ensure that their jobs are maintained. And they are often not even paid for the extra work.

The Portuguese legal system was one of the first in Europe to establish telework in 2003. In 2021, law no. 83/2021 changed the legal regime of telework in the Portuguese Labour Code. Currently, this Labour Code, in Article 165.°, states that teleworking is carried out in a ‘regime of legal subordination of the worker to an employer, in a place not determined by the employer’, through the use of ICT. Thus, the concept of teleworking embraced by Portuguese law is a broad concept that can cover various realities, the essential elements of which are, cumulatively, the fact that the work is carried out outside the company, at a location not indicated by the employer and using ICT. Therefore, according to the Portuguese Labour Code, the main characteristics of teleworking are that the worker is away from the employer’s premises and uses ICT.

According to the Portuguese Green Book Future of Work (2021), it is relevant to note that there are data that point to a significant increase in the willingness to resort to telework by companies, since according to a survey conducted by the confederation of employers’ CIP, ‘48% of companies surveyed intend to use this form of work, and among these, only 22% consider telework situations in which workers stay five days a week in this regime’ (MTSSS 2021, p. 51). This study notes that the cost reduction and motivation of workers are the main advantages of telework mentioned by employers while the dispersion of workers with domestic and family tasks and the lack of communication between teams are identified as the main disadvantages (idem). As has also been pointed out, some of the advantages of teleworking for employers include greater labour efficiency and productivity and the possibility of adopting management by objectives or results schemes (idem).

However, telework may also have disadvantages and involve specific risks, namely regarding the (non)limitation of working time. In effect, telework, if not duly safeguarded, may make the worker not disconnect from work and work more hours than usual, with an increase in stress and other psychosocial risks (Pinsonneault and Boisvert 2001; Eurofound 2017).

Moreover, teleworking may particularly penalise women, who traditionally continue to be responsible for domestic and care work to a greater extent than men, aggravating the difficulties in terms of reconciling professional, family, and personal life (MTSSS 2021). As the Portuguese Green Book points out, the resolution on the right to disconnect proposed by the European Parliament, adopted on 21 January 2021, recommends the adoption of a directive on this issue (European Parliament 2021). This resolution stresses the importance of telework in safeguarding employment during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also warns of the negative impact on workers’ well-being resulting from the possible increase in working time (MTSSS 2021, p. 94). As this document states, this resolution makes recommendations that employers should not be able to require workers to be available outside working hours. It also seeks to ensure that workers who invoke their right to disconnect are protected against possible repercussions. This Green Book highlights that “teleworking has blurred the boundaries between working time and non-working time”, intensifying working time and deteriorating “the conditions for reconciling professional, personal and family life” (ibidem).

Although the Portuguese Labour Code seeks to minimise the problems associated with telework, determining that the worker must be treated in equal conditions to other workers working in the company’s premises and that the employer should respect the privacy of teleworkers and their working hours, problems with overworking persist. This especially applies as Portugal is one of the European Union countries with the highest average working hours per week. According to Eurofound data in 2018, in the EU28, the usual working week was 40.2 h and in the EU15, it was 40.1 h, with Portugal (40.8 h) standing out as the country with the highest weekly working time (Eurofound 2019).

As mentioned above, until the appearance of the COVID-19 pandemic, the legal regime of telework seemed adjusted and there was adherence to this form of work provision; until the beginning of 2020, it was residual in most countries, but with the pandemic, it became massive. In this respect, it is also worth mentioning that an ILO study on the impact of COVID-19 on the Portuguese economy and labour market, presented in 2020, highlights the importance of teleworking (ILO 2020b). As we mentioned, in Portugal, with the pandemic, the generalisation of teleworking has become a special challenge. In a country not used to teleworking—since, as this study highlights, in 2019, only ‘6.5% of Portuguese employees worked from home’ (ILO 2020b, p. 10)—in Portugal, teleworking was carried out under demanding conditions, especially for families with children.

In addition, in 2020, a study sought to know the position of the Portuguese social partners on various issues related to working time. This investigation was based on two lines of research: first, equality at work and work–life balance, and second, digital work/telework and working time (Rebelo et al. 2020). The first axis included several dimensions of working time, such as the importance of flexibility; the work–family balance; the acceptability of receiving after-hours contacts through technologies; the right to disconnect; and the relationship between working time and telework. As for the second axis of research, it included, in particular, the following issues: teleworkers’ autonomy and benefits of teleworking and a mixed regime (telework and face to face); differences between teleworkers and face-to-face workers’ professional and personal profiles; the impact of telework on work–life balance; and the role of companies and collective bargaining in the implementation of telework policies. This study adopted a qualitative approach based on semi-structured interviews. The interviews were addressed to the Portuguese social partners, members of the Economic and Social Council: two trade union confederations and one employers’ confederation. These interviews were conducted before the right to disconnect was enshrined in the Portuguese Labour Code by law 83/2021, of 6 December 2021, and, as already mentioned, their structure was based on dimensions that generated several questions related to the possibility of working after normal working hours using new technologies (idem). In this study, the employers’ confederation has considered that the right to disconnect is ‘advisable as long as it is not confused with the obligation to disconnect’ (idem). The conclusions of this study that can be drawn from the above excerpts from the statements of the Portuguese social partners is that the “right to disconnect” was not understood as an obligation or duty of the worker to disconnect, but as a principle to be respected in order to achieve a better balance between family and professional life. In this study, it should be noted that, in the opinion of the confederations interviewed, the evolution of telework through the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised the emergency of the right to disconnect.

3. Results

In 2021, a survey on working time was carried out among women with an employment contract (a non-probability sample). This survey sought to find out whether, during the years 2020 and 2021, teleworking women were able to reconcile their professional lives with their personal and family lives and, in particular, to ask about the importance of the right to disconnect from work. A statistical analysis was applied to this survey. The association between categorical variables was analysed using the Chi-square test (Agresti 2002). Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. The statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows programme, version 27.0.

This survey was structured in two parts, one with a personal and contractual profile and the other part on working time and conditions, with a total of 16 questions. It is also worth mentioning that our survey on working time was applied via the internet, on a social network, using Google Forms, between 7 November and 15 December 2021. At the start of the online survey, all participants were informed of the purpose of the research and were asked for their informed consent, ensuring their anonymity and the confidentiality of their answers and their use for statistical purposes only. Participation was voluntary. It was answered by 155 women with employment contracts. In terms of the socio-demographic characteristics of study respondents, 49.0% were aged 36 to 50 years old, 30.3% were 51 or older, and 20.7% were aged 18 to 35 years old. Analysing by ”marital status versus age group”, in the 18–35 age group, the majority of respondents were single (59.4%); in the 36–50 age group, the majority of respondents were married or cohabiting (57.9%); and in the 51+ age group, 66.0% of respondents were married or cohabiting. Regarding marital status, 56.1% of the women were married or living in a consensual union, 27.7% of respondents were single, and 16.1% were divorced or separated. With regard to the number of children, 36.1% of respondents answered as having none, 31% had one child, 28.4% had two children, and 4.5% had three or more children. In addition to that, 40.6% of women surveyed replied that they had a post-graduate, master’s, or doctorate degree; 40.0% had a degree; 18.1% attended school up to the 12th grade; and 1.3% attended school up to the 9th grade. Furthermore, 38.7% of women replied that they were technicians, 23.9% directors or managers, 14.2% teachers and researchers, 11.6% administrators, and also 11.6% other categories (not defined).

Of the total women surveyed, 79.4% said that they had been teleworking in 2020 and 2021 (Q.13). On whether teleworkers had had more availability for personal and family life (Q.14), 57.0% of the women surveyed responded that they felt more availability for personal and family life and 43.0% answered that they did not feel more available for their personal and family life. Then, still related to question 14, the following research hypotheses were put forward: Is the feeling of having more time available independent of your level of education? Is the feeling of having more time available independent of marital status? Is the feeling of having more time available independent of professional category? Is the feeling of having more time available independent of age group? And—through the association between categorical variables analysed by the Chi-square test—it was possible to conclude that

- -

- ‘Whether or not they feel they have more time for their personal and family life’ is associated with marital status ( = 6.385), p-value = 0.041;

- -

- ‘Whether or not they feel they have more time for their personal and family life’ is not associated with educational level ( = 3.635), p-value = 0.162;

- -

- ‘Whether or not they feel they have more time for their personal and family life’ is not associated with the professional category ( = 6.442), p-value = 0.168;

- -

- ‘Whether or not they feel they have more time for their personal and family life’ is not associated with the age group ( = 3.282), p-value = 0.194.

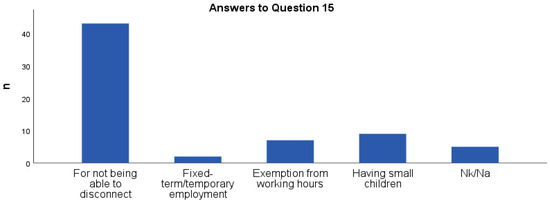

In question 15, of the women who answered no to Q.14, the vast majority (82.7%) considered that it was because they could not disconnect from the activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons for having less time available in telework (Q.15).

The profile of women who identified ‘not being able to disconnect from their work’ while teleworking was analysed by taking into account age, marital status, and number of children (Table 1) and age, educational level, and professional category (Table 2). It turns out that 62.8% of the respondents were between 36 and 50 years old, 23.3% were 51 or older, and 14% were between 18 and 35 years old. In the dominant age group, between 36 and 50 years old, 66.7% of the women were married or living in a consensual union (Table 1) and 44.4% had a post-graduate, master’s, or doctorate degree (Table 2). Among these 44.4% women, there were 41.7% technicians, 16.7% directors or managers, and 33.3% teachers and researchers (Table 2).

Table 1.

Profile of women who answered “for not being able to disconnect” to Q.15 (by age group, marital status, and number of children).

Table 2.

Profile of women who answered “for not being able to disconnect” to Q.15 (by age group, educational level, and professional category).

4. Discussion

In the context of this study, there were three main results of this survey: the first was to identify that—during the pandemic—the majority of women felt more available for themselves and their families when teleworking; the second was to identify that women’s perception of having more time for personal and family life is related to their marital status; the third was to verify that the vast majority of women who answered that they had less time for themselves and their families considered that it was because they were unable to disconnect from the activity beyond the contracted hours.

Thus, on the one hand, these results corroborate the thesis that the majority of women (57.0%) experienced greater availability for personal and family life. These results confirm the studies highlighting the benefits of teleworking for workers (Felstead and Henseke 2017; Lott and Abendroth 2019; ILO 2020a, 2020c; Santos and Pereira 2023). They also confirm the study by Tan et al. (2024), according to which there is a positive impact of teleworking on life satisfaction, mediated by work–life balance. These results corroborate the study carried out by Eurofound and ILO (2017) and the idea that the growing use of teleworking has been driven by companies’ demands for better performance and that it is linked to the demand for more efficient and faster work processes and also to the desire to help employees reconcile work with family and personal life. Furthermore, as the study by Felstead and Henseke (2017) points out, given the demographic pressures on the labour force, teleworking appears as an opportunity for ‘working parents’, allowing them to reconcile work and family life. This also confirms the results of the Eurofound (2023b) study, which indicates that telework has led to greater working time autonomy, allowing teleworkers to schedule their work hours to fit their personal circumstances.

However, with regard to the results obtained through the association between categorical variables analysed using the Chi-square test, it was possible to conclude that women’s perception of having more time for their personal and family life is associated with marital status. On the other hand, this perception of having more time available for personal and family life is not associated with the level of education, professional category, or age group. This study confirms that teleworking is particularly detrimental to married women, who traditionally continue to be primarily responsible for domestic and care work, as confirmed by the study by MTSSS (2021). Due to the persistent division of gender roles, differences in work–life balance remain, particularly harming women with family responsibilities. The results show that the majority of women who reported having more time for personal and family life were single or divorced/separated. It will be important to continue researching this topic, not least because if the literature before the COVID-19 pandemic identified teleworking with the benefits of women, particularly married women (Shojanoori et al. 2015), this pandemic (with mandatory teleworking) may have been disruptive in this respect. It will be important to continue studying this impact on non-mandatory teleworking.

Finally, the results show that the vast majority of women who replied that they had less time for themselves and their families considered this to be due to the fact that they were unable to disconnect from their work beyond the contracted hours. These results tend to follow the studies by Kelliher and Anderson (2010) and Molm et al. (1999), so more research is needed into the idea that remote workers see teleworking as a benefit and, in a logic of exchange/reciprocity, tend to spend more time working in this form of work organisation. To this extent, it will be important not only to assess the changes—which have been maintained—in the organisation of work after the pandemic, but also the effective fulfilment of the recently enshrined right to disconnect. This study also accompanies studies that identify the problem of inequalities in teleworking posed by the development of ICT, giving centrality to the right to disconnect (Miernicka 2024).

The findings of this study also corroborate the studies of Zhang et al. (2020) and Kurowska (2020), which highlight the significant impact of teleworking on work–life balance, particularly as companies increasingly expect employees to maintain a constant connection and address work-related issues outside of normal working hours. Additionally, the findings support Reid and Ramarajan’s (2016) study, which indicates that the expansion of technological resources at work makes it challenging for both men and women to focus solely on work while simultaneously managing other aspects of their lives.

On the other hand, this study follows the literature (Zlatanović and Škobo 2023) that recommends a further evaluation of the impact of the constant availability of workers in the digital age society, in particular by understanding how the so-called “right to disconnect” can serve to respond to the problem of psychosocial risks associated with the digital age. Given the scarcity of studies specifically on the right to disconnect, the findings of the present study make it possible to contribute to future studies on this subject, which is still little explored and is becoming increasingly important given the growing use of ICT and the expansion of teleworking in the labour market. And these are findings that should be studied further in future research.

While there is currently no legal framework in the European Union directly regulating the right to disconnect, it will be important that in the various countries that have already established their regulations—such as Portugal in 2022—their practical impact is assessed in future empirical research. More than the right to disconnect, it is related to achieving a better work–life balance and creating a healthy working environment.

5. Conclusions

The unexpected COVID-19 pandemic has especially transformed the Portuguese labour market, through the increased use of telework. This situation has shown that the impact of megatrends is difficult to predict, leading to employers having to prepare for constant change. And that will require strategic and dynamic workforce planning that moves from annual to real time as health conditions and business plans change. In addition, the movement of technological change and digital transition raises the issue of work organisation, in particular the management of working time.

As highlighted in this paper, teleworking gives workers more availability due to the elimination of daily commuting but telework can also lead to work intensification when combined with heavy workloads and work cultures dominated by precarious employment and individualism. As can be seen from the literature review in this article, the work organisation can affect the lives of workers at various levels, including their health and their family and personal life. As a form of work largely supported by new technologies, telework poses new social challenges, the organisation of working time being one of the most relevant. Telework can have disadvantages and involve specific risks, namely regarding the (non)limitation of working time; conciliation between personal, family, and professional life; working conditions; and health and safety at work.

As the literature has shown, the increasing use of ICTs by workers tends to lead to higher levels of work intensity. Hence, the literature has developed the concept of the right to disconnect, based on this new requirement of labour law in the face of technology. This may lead to a new paradigm for the regulation of working time. In countries such as Portugal, with a high average number of working hours per week, this issue of the right to disconnect assumes greater importance. Workers should be able to enjoy real rest time. Hence, in several European countries—namely Portugal, in January 2022—the ‘right to disconnect’ has been enshrined in law.

Hence, this article has investigated women’s perspectives on the impact of working time management on their working conditions, seeking to analyse the specific importance of the right to disconnect. From our survey on “working time”, launched in 2021 among employed women with a work contract, it should be noted that of the women surveyed who recognised that teleworking made less time available for themselves, the vast majority considered this to be due to the fact that, when teleworking, they could not disconnect from their work beyond working hours.

From this survey, it was possible to conclude that the perception of having less time at work is associated with the marital status of the respondents. Of all the women who said that they did not have more time available from teleworking than from face-to-face work, 82.7% answered that it was because they ‘were unable to disconnect’. The profile of women who identified as ‘not being able to disconnect from their work’ while teleworking was also analysed. Most of the literature confirms that teleworking is a type of work that—for employees—has the main advantage of greater time availability (mainly due to the elimination of daily home–work journeys). However, the results of this study show that some respondents consider that teleworking does not allow for this greater availability, and a very significant number of these respondents (82.7%) consider that this is because, after working hours, “they are unable to disconnect”. These results align with previous studies that emphasise the importance of research on the impact of teleworking on work–life balance, since companies demand a permanent connection from employees even beyond normal working hours.

Nevertheless, there are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that, due to resource constraints, the analysis was based on a non-probability sample and the data cannot be generalised. It is therefore an exploratory study. In addition, the fact that the survey was carried out online (namely on social media) may explain why a higher percentage of women have post-graduate, master’s, doctorate, or bachelor’s degrees. Therefore, the sample may only be representative of highly educated women and the results of the study may not be generalisable. This is also true in terms of the professional categories of the respondents, since the two main groups are women technicians or directors or managers. Although this study has limitations, these results highlight the importance of assessing the right to disconnect in teleworking activities. Especially at a time when the hybrid working modality—a mix of face to face and teleworking—has expanded in companies. And they corroborate the need to continue a study that links the exercise of teleworking and the right to disconnect. Furthermore, this is particularly important in countries with a high level of job insecurity and long working hours, such as Portugal. Teleworking can ensure (or even increase) productivity while allowing employees to enjoy greater well-being, if certain management measures are adopted. Teleworking is beneficial for most workers, as it allows them to stop travelling from home to work, freeing up time to reconcile work and family life, but it can also intensify work in some cases. That is why it is crucial to identify in future research the population groups where this situation tends to occur.

As the findings of this study show, teleworking is beneficial for the majority of workers, as it allows them to stop travelling from home to work, freeing up time to reconcile work and family life; but it can also, as this study shows, intensify work for married women or women in a non-marital partnership. It is therefore essential to identify in future research the population groups where this situation tends to occur, and in particular whether they are associated with marital status. Furthermore, both to analyse the impact of the expansion of teleworking in the aftermath of the pandemic and to analyse the negative impact of technology on work (in particular the permanence of the electronic connection to work), it is necessary to continue researching the impact of enshrining the right to disconnect in law and to assess its legal effectiveness and benefits for both companies and employees.

In conclusion, while the results of this study confirm certain trends observed in previous research on the impact of telework on work–life balance for workers, they also highlight the need for a more nuanced analysis. Future research should delve deeper into the role of gender and marital status, as married women appear to face greater challenges in disconnecting from work. Additionally, the potential disruptive effects of the pandemic, particularly the distinction between mandatory and non-mandatory teleworking, warrant further investigation. Finally, the effective implementation of the right to disconnect across different national contexts remains an open area for exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.; methodology, G.R., C.D. and M.F.D.; data curation, G.R., C.D. and M.F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.; writing—review and editing, G.R., C.D., M.F.D. and A.R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical analysis and approval were waived for this study since it did not involve any particular institution and all individual participants did so voluntarily and with their written informed consent. In addition, all ethical research practices that protected the rights of the participants in this research were followed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Sample data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adascalitei, Dragos, and Jason Heyes. 2021. Labour markets in post-crisis Europe: Liberalisation, deregulation, precarisation. In Handbook on Austerity, Populism and the Welfare State. Edited by Bent Greve. London: Edward Elgar, pp. 344–59. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, Alan. 2002. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Tammy D., Timothy D. Golden, and Kristen M. Shockley. 2015. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Psychological Science in the Public Interest 16: 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askenazy, Philippe. 2004. Shorter work time, hours flexibility, and labor intensification. Eastern Economic Journal 30: 603–14. [Google Scholar]

- Avogaro, Matteo. 2018. Right to Disconnect: French and Italian Proposals for a Global Issue. Revista Direito das Relações Sociais e Trabalhistas 4: 110–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniell, Inés, and Jan Bientenbeck. 2017. The Effect of Working Hours on Health. IZA DP 10524 IZA—Institute of Labor Economics. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/izaizadps/dp10524.htm (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Burchell, Brendan. 2002. The prevalence and redistribution of job insecurity and work intensification. In The Prevalence and Redistribution of Job Insecurity and Work Intensification: Job Insecurity and Work Intensification. Edited by Brendan Burchell, David Ladipo and Frank Wilkinson. London: Routledge, pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Iain, and Brigid Van Wanrooy. 2013. Long working hours and working-time preferences: Between desirability and feasibility. Human Relations 66: 1131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, Rosemary, Duncan Gallie, and Kate Purcell. 1996. Changing Forms of Employment—Organisations, Skills and Gender. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Degryse, Christophe. 2016. Digitalisation of the Economy and Its Impact on Labour Markets. ETUI Research Paper—Working Paper. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute (ETUI). [Google Scholar]

- Dembe, Allard. 2009. Ethical issues relating to the health effects of long working hours. Journal of Business Ethics 84: 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembe, Allard E., J. Bianca Erickson, Rachel G. Delbos, and Steven M. Banks. 2005. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62: 588–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, Daantje, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. The Impact of E-mail Communication on Organisational Life. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 4: 4. Available online: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/4233 (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Duxbury, Linda, and Michael Halinski. 2014. When more is less: An examination of the relationship between hours in telework and role overload. Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation 48: 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, Linda, Christopher Higgins, and Derrick Neufeld. 1998. Telework and the balance between work and family: Is telework part of the problem or part of the solution? The Virtual Workplace 218: 55. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2006. Working time and work-life balance in European companies (overview report of the ESWT). In European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2009. Working Conditions in the European Union—Working Time and Work Intensity. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2010. Telework in the European Union. Luxembourg: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2013. Organisation of Working Time: Implications for Productivity and Working Conditions—Overview Report. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2015. Opting out of the European Working Time Directive. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2017. Working Time Developments in the 21st Century—Work Duration and Its Regulation in the EU. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2018. Striking a Balance: Reconciling Work and Life in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2018/striking-balance-reconciling-work-and-life-eu (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Eurofound. 2019. Working Conditions and Workers’ Health. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2020a. European Company Survey 2019—Workplace Practices Unlocking Employee Potential. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions and European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2020b. Labour Market Change: Trends and Policy Approaches towards Flexibilisation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2020/labour-market-change-trends-and-policy-approaches-towards-flexibilisation (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Eurofound. 2020c. Right to Disconnect in the 27 EU Member States. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/eurofound-paper/2020/right-disconnect-27-eu-member-states (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Eurofound. 2020d. Telework and ICT-Based Mobile Work: Flexible Working in the Digital Age. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2023a. Right to Disconnect: Implementation and Impact at Company Level. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2023/right-disconnect-implementation-and-impact-company-level (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Eurofound. 2023b. The Rise in Telework: Impact on Working Conditions and Regulations. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2022/rise-telework-impact-working-conditions-and-regulations (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Eurofound, and the International Labour Office (ILO). 2017. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work. Geneva: Publications Office of the European Union and the International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2010. Europe’s Digital Competitiveness Report. Report on Digital Competitiveness in Europe—Main Objectives of the i2010 Strategy for 2005–2009. European Commission. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2009:0390:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- European Commission. 2015. New Forms of Employment. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020. Europe’s Digital Progress Report (EDPR) 2017. Country Profile Portugal. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2021. European Parliament Resolution of 21 January 2021 with Recommendations to the Commission on the Right to Disconnect (2019/2181(INL)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0021_EN.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Felstead, Alan, and Golo Henseke. 2017. Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work-life balance. New Technology, Work and Employment 32: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. 2017. How Engaged Is Your Remote Workforce? New York: Gallup. [Google Scholar]

- Ganster, Daniel C., Christopher C. Rosen, and Gwenith G. Fisher. 2018. Long working hours and well-being: What we know, what we do not know, and what we need to know. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershuny, Jonathan. 2000. Changing Times: Work and Leisure in Postindustrial Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, Timothy D., and Sumita Raghuram. 2010. Teleworker knowledge sharing and the role of altered relational and technological interactions. Journal of Organisational Behavior 31: 1061–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Melissa, Katrina A. Lambert, Victoria Weale, Rwth Stuckey, and Jodi Oakman. 2023. Working from home during the COVID 19 pandemic: A longitudinal examination of employees’ sense of community and social support and impacts on self-rated health. Bmc Public Health 23: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Christine A., Louise Margaret Wallace, and Peter C. Spurgeon. 2013. An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Employee Relations 35: 527–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, Tomika W., and Stephanie C. Payne. 2014. Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. The Psychologist-Manager Journal 17: 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselberth, Pepita. 2018. Discourses on disconnectivity and the right to disconnect. New Media and Society 20: 1994–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, and Carolyn Buck Luce. 2006. Extreme jobs: The dangerous allure of the 70-h workweek. Harvard Business Review 84: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, John. 2024. Managing the Right to Disconnect—A Scoping Review. Sustainability 16: 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2018. Decent Work in Portugal 2008—2018: From Crisis to Recovery. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020a. Defining and Measuring Remote Work, Telework, Work at Home and Home-Based Work. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020b. Portugal—Rapid Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Economy and Labour Market. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020c. Teleworking during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond—A Practical Guide. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Jungryeol, Park, and Kwon Sundong. 2020. A Study on the Effect of the Right to Disconnect on the Job Satisfaction. Journal of Information Technology Applications and Management 27: 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, Clare, and Deirdre Anderson. 2010. Doing More with Less? Flexible Working Practices and the Intensification of Work. Human Relations 63: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ellen E., and Brenda A. Lautsch. 2012. Work–family boundary management styles in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review 2: 152–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, Anna. 2020. Gendered effects of home-based work on parents’ capability to balance work with non-work: Two countries with different models of division of labour compared. Social Indicators Research 151: 405–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, Beverly, and Owen Leeds. 2003. Telework: Family friendly or employer friendly? In Organisation and Work Beyond 2000. Edited by B. Rapp and P. Jackson. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag, pp. 157–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wei, Jun-Quan Zhang, Jing Sun, Ji-Hong Ke, Zhi-Yuan Dong, and Sheng Wang. 2007. Job stress related to glyco-lipid allostatic load, adiponectin and visfatin. Stress and Health 23: 257–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, Kate, and Tom Harnish. 2011. The State of Teleworking in the US: How Individuals, Businesses, and Government Benefit. Teleworker Research Network 2011: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, Kate, and Tom Harnish. 2019. Telework and its effects in the United States. In Telework in the 21st Century. Edited by Jon C. Messenger. London: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 128–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, Yvonne, and Aanja Abendroth. 2019. Reasons for not Working from Home in an Ideal Worker Culture: Why Women Perceive More Cultural Barriers. WSI Working Paper 211. Düsseldorf: The Institute of Economic and Social Research (WSI). [Google Scholar]

- Menon, Seetha, Andrea Salvatori, and Wouter Zwysen. 2020. The Effect of Computer Use on Work Discretion and Work Intensity: Evidence from Europe. BJIR An International Journal of Employment Relations 58: 1004–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miernicka, Irmina. 2024. The Right to Disconnect as a Tool to Tackle Inequalities Resulting from Remote Working. In Work Beyond the Pandemic- Towards a Human-Centred Recovery. Edited by Tindara Addabbo, Edoardo Ales, Ylenia Curzi, Tommaso Fabbri, Olga Rymkevich and Iacopo Senatori. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 133–49. [Google Scholar]

- Molm, Linda D., Gretchen Peterson, and Nobuyuki Takahashi. 1999. Power in negotiated and reciprocal exchange. American Sociological Review 64: 876–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MTSSS. 2021. Livro Verde Sobre o Futuro do Trabalho. Lisbon: MTSSS. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, Nicholas R. 2009. Social isolation in older adults: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65: 1342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, Jack M. 1988. Traffic reduction by telecommuting—A status review and selected bibliography. Transportation Research Part A: General 22: 301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2013. Measuring the Internet Economy: A Contribution to the Research Agenda. OECD Digital Economy Papers, 226. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2016. New Forms of Work in the Digital Economy. OECD Digital Economy Papers 260. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pansu, Luc. 2018. Evaluation of ‘Right to Disconnect’ Legislation and Its Impact on Employee’s Productivity. International Journal of Management and Applied Research 5: 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiperl, Maury, and Yehuda Baruch. 1997. Back to Square Zero: The Post-Corporate Career. Organisational Dynamics 25: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, Agnieszka. 2018. Scheduled to work hard: The relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers (2005–2015). Human Resource Management Journal 28: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, Agnieszka. 2020. Standards of good work in the organisation of working time: Fragmentation and the intensification of work across sectors and occupations. Management Revue 31: 259–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsonneault, Alain, and Martin Boisvert. 2001. The Impacts of Telecommuting on Organisations and Individuals—A Review of the Literature. In Telecommuting and Virtual Offices: Issues and Opportunities. Edited by Johnson N. Hershey. Hershey: Idea Group Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Jean-Emmanuel. 2016. Grande accélération et droit à la déconnexion. Droit Social 11: 912–20. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/1876ecc9d4055a8be057ec0a21745560/1?pq-origsite=gscholarandcbl=396456 (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Rebelo, Glória, Eduardo Simões, and Isabel Salavisa. 2020. Working time and digital transition: A complex and ambiguous relationship. In Proceedings of the European Conference on the Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, ECIAIR 2020. Edited by Florinda de Matos. Lisbon: Academic Conferences International, pp. 128–35. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Erin, and Lakshmi Ramarajan. 2016. Managing the High-Intensity Workplace. Harvard Business Review 94: 78–85. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=51141 (accessed on 23 December 2023).

- Rice, Virginia Hill, ed. 2012. Theories of stress and its relationship to health. In Handbook of Stress, Coping, and Health: Implications for Nursing Research, Theory, and Practice, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 22–42. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/44175_book_item_44175.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Santos, Reinaldo Sousa, and Sílvia dos Santos Pereira. 2023. For Telework, Please Dial 7–Qualitative Study on the Impacts of Telework on the Well-Being of Contact Center Employees during the COVID19 Pandemic in Portugal. Administrative Sciences 13: 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojanoori, Forough, Fatemeh Khademi, and Samaneh Sadatsadidpour. 2015. Analysis of effects of employed married women teleworking on keeping balance between work and family. Women’s Studies Sociological and Psychological 13: 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Jolene, Jeremy Lim-Soh, and Poh Lin Tan. 2024. The Impact of Teleworking on Women’s Work–Life Balance and Life Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Study from Singapore. Applied Research in Quality of Life. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11482-024-10340-x#citeas (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Tugend, Julie, Gianreto Manatschal, Nick J. Kusznir, Emmanuel Masini, Geoffroy Mohn, and Isabelle Thinon. 2014. Formation and deformation of hyperextended rift systems: Insights from rift domain mapping in the Bay of Biscay-Pyrenees. Tectonics 33: 1239–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shihang, Rolf Moeckel, Ana Tsui Moreno, Bin Shuai, and Jie Gao. 2020. A work–life conflict perspective on telework. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 14: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatanović, Sanja S., and Milena Škobo. 2023. The ‘Twilight’ of Health, Safety, and Well-being of Workers in the Digital Era–Shaping the Right to Disconnect. Journal of Work Health and Safety Regulation 2: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).