Abstract

The concept of resilience has gained significant prominence across various disciplines, particularly in the context of regional development. Specifically, the Social Responsibility of Local Public Administrations (SRLPA) may play a significant role in fostering resilient territories. This study proposes a second-order model utilizing Structural Equation Modeling—Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) to investigate the complex relationships between the SRLPA and citizen participation in municipal affairs. The proposed model comprises six dimensions for the SRLPA: good governance values, efficiency, transparency, economic issues, environmental concerns, and socio-labor matters. One of the primary contributions of this study is the development and operationalization of a scale designed to measure the construct of the SRLPA. Additionally, empirical analysis shows that the relationship between the SRLPA and citizen participation is indirect. Instead, SRLPA exerts its influence through two mediating variables: citizen connection with the municipality and the perceived bond with the local government. The findings suggest that to positively impact citizen participation, the SRLPA must strengthen relationships with citizens, thereby enhancing their engagement in municipal affairs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of resilience has gained significant prominence across various disciplines such as regional development, particularly in the context of cities and climate change. While definitions and measurement methods may vary among sources, there is a broad consensus on two critical points. The first is urban resilience, referring to the need for territories to fortify themselves against a diverse array of shocks and stresses arising from climate change (Meerow et al. 2016; Ribeiro and Gonçalves 2019). These challenges demand adaptive strategies that enhance a territory’s capacity to withstand and recover from disruptions. The second critical point is the effort to create synergies with urban and sustainable development (Zeng et al. 2022). The efforts to bolster resilience should be integrated with initiatives aimed at promoting urban development and sustainability. For instance, promoting synergies between urbanization and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Chen et al. 2022). The interplay between these dimensions is considered essential for creating robust and thriving environments. We argue that the Social Responsibility of Local Public Administrations (SRLPA), seen as an adaptation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to public entities at the local level (Sánchez-Hernández et al. 2020), may contribute to fostering resilient territories. Aligning regional development, sustainability, and innovation could support municipalities in adapting to change while addressing the well-being of their inhabitants and the environment.

Much has been written in the social sciences about CSR. However, the academic literature on the SRLPA as an expression of democracy and the link to the processes of citizens’ involvement in urban resilience is still at an early developmental stage (LopezDeAsiain and Díaz-García 2020; Levitsky and Way 2023). After reviewing the scarce antecedents of the topic, this work offers the conceptualization of the SRLPA, a tentative scale for approaching the construct, a theoretical model linking it with citizen participation as an expression of real democracy (Michels 2011), and a path for building community resilience (Mahajan et al. 2022). In addition to validating the scale and the model, an empirical study is carried out with a convenient sample of 669 citizens in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura, Spain, located in the west of the country on the border with Portugal. It is important to highlight that the region is classified as a “Less Developed Region” by the European Union (EU) (Nieto Masot et al. 2019). This classification is based on specific economic criteria used by the EU to allocate structural funds aimed at promoting development and reducing disparities between regions. At the same time, this region is considered a resilient territory due to its ability to anticipate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disturbances and changes, whether economic, social, environmental, or institutional in nature (Gómez-Ullate et al. 2020; Navinés et al. 2023).

Several factors contribute to resilience in Extremadura. The territory has made significant efforts to diversify its economy (Madeira et al. 2021). Traditionally dependent on agriculture, the region has been developing sectors such as rural tourism (González-Ramiro et al. 2016), the agri-food industry (Martínez-Azúa and Martín-Vegas 2019), and renewable energy (Jeong and Ramírez-Gómez 2018). Extremadura, which possesses important natural resources, such as water and fertile soils, has significantly invested in solar energy and biomass, developed strategies to adapt to climate change by implementing sustainable agricultural practices, and is efficiently managing its water resources (González-González et al. 2014). It is also relevant that the region has a public university and several research centers that promote innovation and the development of local skills (Gallardo-Vázquez and Folgado-Fernández 2020). Additionally, communities in Extremadura often have strong social ties and a high degree of cohesion, which is crucial for social resilience in times of crisis (Gurría Gascón and Nieto Masot 2020). To reinforce all these factors, regional policies and support from the EU, through structural and cohesion funds have been vital in driving development and modernization projects in the region. These policies foster institutional and economic resilience by providing the necessary resources to face challenges and seize opportunities.

Despite recent progress, Extremadura has faced challenges that may impact its resilience, particularly depopulation, and an aging population, especially in rural areas (Serra et al. 2023). However, the findings from this exemplary European case study suggest that efforts to foster and enhance the SRLPA can contribute to strengthening local democracy, promoting sustainable development from the grassroots level, and creating a pathway toward more resilient territories. Extremadura was selected as the case study due to its unique socio-economic and demographic characteristics, offering a meaningful context for examining SRLPA and citizen participation. Its low population density, rural landscape, and policy initiatives aimed at boosting civic engagement make it an ideal setting for understanding patterns that may be applicable to other similar regions, thus enhancing the generalizability of the findings

The first objective of this work is to define and clarify the concept of the SRLPA, focusing specifically on the social responsibility of Municipal Councils. The second objective is to develop a tentative measurement scale that accurately captures the construct of the SRLPA. The third objective is to construct a theoretical model linking the SRLPA with citizen participation. This model will be empirically validated, to assess how SRLPA efforts contribute to promoting local democracy, sustainable development, and territorial resilience.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Social Responsibility of Local Public Administrations

Although public administrations might be assumed to be socially responsible a priori, reported cases of poor social or environmental practices and corruption indicate otherwise (e.g., Villoria et al. 2013; Meza and Pérez-Chiqués 2021; Romano et al. 2021). Thus, the SRLPA is not yet institutionalized and cannot be taken for granted (Green et al. 2009).

In general terms, the SRLPA refers to the ethical and proactive commitment of local government bodies to contribute positively to society, the environment, and their communities. The SRLPA goes beyond providing services and maintaining infrastructure. It involves fostering an environment where citizens can actively participate in decision-making processes, hold their local government accountable, and contribute to the sustainable development of their community (Ricciardelli 2018). This active engagement of citizens in local governance is a cornerstone of a healthy democracy (Michels and De Graaf 2010; Sánchez-Hernández et al. 2020; Hendriks and Dzur 2021). There are some key issues to understanding this novel concept.

First, the Triple Bottom Line Approach, originally defined by Elkington (1998), addresses the economic, social, and environmental goals of businesses in the 21st century. The SRLPA requires local councils to actively consider social and environmental factors in their decision-making processes. It transcends mere legal obligations emphasizing a genuine commitment to the well-being of citizens and the planet. It encompasses three interconnected dimensions. One dimension is social inclusion, ensuring that policies and actions benefit all community members, especially vulnerable groups. For instance, incorporating the 2030 Agenda into local policies for social transformation (Ríos et al. 2022; Vela-Jiménez et al. 2022). Another dimension is environmental sustainability, promoting practices that protect natural resources, reduce pollution, and mitigate climate change. In this respect, Serrao-Neumann et al. (2015) studied public participation levels in specific local contexts in Australia regarding climate change adaptation. The third dimension is economic development, which balances economic growth with social and environmental well-being (Bennett et al. 2004). Additionally, recent works such as Cárcaba et al. (2023) in Spain focus on the subjective well-being of citizens.

Second, in the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) approach, the SRLPA aligns with the SDGs, which aim to create more empathetic, resilient, and just societies. Local governments play a crucial role in implementing SDGs at the community level by addressing issues related to social inclusion, environmental sustainability, and economic development (Silva et al. 2023a).

Third, in the Co-Creation and Stakeholder Engagement approach, the SRLPA encourages local administrations to actively involve stakeholders, such as citizens, businesses, and civil society organizations, in shaping policies and solutions. It recognizes that sustainable development requires collaborative efforts and participatory decision-making (Sarmah et al. 2015).

In summary, the SRLPA concept encompasses the social responsibility of municipalities through its multi-dimensional approach that addresses economic, social, and environmental concerns, intersecting with territorial resilience as discussed in the next section.

2.2. Linking SRLPA and the Resilience of a Territory under the Lends of Institutional Theory

Territorial resilience refers to the capacity to withstand, adapt to, and recover from various shocks, stresses, and disturbances, such as natural disasters, climate change impacts, social disruptions, or economic challenges (Toseroni et al. 2016; Pignatelli et al. 2019; Oliva and Olcina 2022). It involves the ability to absorb and respond to these challenges while maintaining essential functions, services, and structures, ultimately bouncing back stronger and more sustainably after a crisis (Houston 2018).

Institutional Theory is a framework for understanding how institutions—defined as established laws, practices, and customs—shape social behavior and organizational structure (David et al. 2019). The theory posits that the nature and variety of institutional processes influence organizational behavior (Oliver 1991; Lawrence and Shadnam 2008), as well as of organizations belonging to public administrations (Carpenter and Feroz 2001; Hronec et al. 2022). Institutional forces, both internal (e.g., the commitment of the municipal government’s team) and external (e.g., citizen pressure, national or international normative pressure), drive public institutions to be more ethical and socially responsible (Amaeshi et al. 2016; Risi et al. 2023).

This theory explains how institutions adopt practices and behaviors considered appropriate and legitimate in society. It focuses on the norms, rules, and expectations that influence the actions of these institutions, supporting the importance of the SRLPA in enhancing resilience and fostering regional development (Sjöstedt 2015; Vandergert et al. 2016; Horeczki and Kovács 2023).

In the context of public administration, Institutional Theory provides valuable insights into how public organizations adapt to their environments and maintain legitimacy (Silva et al. 2023b). Public institutions often develop and implement policies that align with societal norms and expectations to ensure public trust and legitimacy (Wallner 2008). Regarding research on the imitation of CSR-related practices, the concept of mimetic isomorphism has been applied to examine different decisions around CSR adoption more thoroughly (Han and Ito 2023). Accordingly, the organizational structures of public agencies may change to mirror successful models in other regions or countries, driven by isomorphic pressures. Regulatory compliance is another critical aspect, as public administrations adhere to established laws and regulations influenced by institutional logic and the need for legitimacy (Lee 2011). Furthermore, institutional change in public administration is evident in the adoption of new technologies, practices, and policies that reflect evolving societal values and norms, as has been demonstrated by Gascó (2003) or Haug et al. (2024). By understanding these principles, public administrators can better navigate the complexities of organizational change and ensure their institutions remain effective and legitimate in the eyes of the public. Concretely, several key components of the SRLPA relate to the principle of legitimacy within the Institutional Theory as follows:

- -

- Law and regulations that institutions must follow (Chiu 2018). Institutional theory argues that public organizations operate in environments governed by both formal and informal norms. The SRLPA enables municipalities to conform to those norms, demonstrating their legitimacy within society. For example, a government may enact laws requiring companies to reduce their carbon emissions, ensuring that companies act responsibly towards the environment.

- -

- Stakeholder dialogues, including conversations and consultations between the institution and the various affected groups (Riege and Lindsay 2006). Institutional theory emphasizes that organizations must manage relationships with stakeholders to maintain legitimacy. Legitimacy is reinforced by how well the municipality meets the broader community’s expectations (Mättö et al. 2020). For instance, a city might organize meetings with citizens, community organizations, and local businesses to discuss sustainable improvements to urban infrastructure.

- -

- Historical and political determinants (Dudchenko and Vitman 2018) refer to how a place’s history and politics influence social responsibility practices. Institutional theory posits that legitimacy is essential for an organization’s long-term survival (Ahn and Park 2018). For example, in a country with a strong tradition of environmental activism, local public administrations are likely to implement stricter environmental policies due to historical and political pressures.

- -

- Social mechanisms such as discourse and normative learning (Bice 2017) are ways in which social and ethical norms are communicated and learned within a society. The SRLPA also encompasses the ethical framework where municipalities are expected to consider their societal and environmental impact, often exceeding mere legal compliance. It includes discursive activities on ethical labor practices, environmental sustainability, and community engagement (Feindt and Oels 2005). For example, public discourse on gender equality can influence organizations to implement policies that promote equality. Normative learning suggests that institutions adopt these ethical norms through education and social interaction.

Regarding territorial resilience, institutions with strong social responsibility are better equipped to handle crises and disruptions (Rizzi et al. 2018). When local public administrations prioritize social responsibility, they invest in building institutional capacities essential for effective crisis management and resilience. This includes enhancing human resources, developing robust emergency response systems, and creating adaptive policies that can respond to changing conditions (Salvador and Sancho 2021, 2023).

Additionally, socially responsible local administrations gain greater legitimacy and trust from their communities. Trust in public institutions is crucial for effective governance and resilience. Local administrations that prioritize citizens’ well-being, transparency, fair practices, and disclosure can potentially enhance trust and legitimacy (García-Sánchez et al. 2013). Social responsibility also enhances social capital and strengthens community networks. These networks are critical for resilience, as they facilitate information sharing, collective action, and mutual support during crises. Local governments that engage with community members and stakeholders build stronger, more resilient networks (Aldunce et al. 2016). Furthermore, socially responsible administrations are more responsive and accountable to their communities. Accountability mechanisms, such as public reporting and community engagement, are hallmarks of socially responsible governance. These mechanisms ensure that local administrations remain responsive to citizens’ needs and concerns (García-Sánchez et al. 2013). This responsiveness is crucial for resilience, as it allows for timely adjustments and interventions in response to emerging threats and opportunities.

According to Fenton and Gustafsson (2017), social responsibility also aligns local governance with long-term SDGs. Responsible administrations prioritize sustainable development, balancing economic growth with social equity and environmental protection. This alignment ensures that regional development is resilient and sustainable, addressing the present needs without compromising future generations’ ability to meet their own needs (WCED 1987). Sustainable development practices build resilience by reducing vulnerability and enhancing communities’ adaptive capacity (Benito et al. 2023).

Finally, social responsibility fosters community empowerment and active participation in governance. When local administrations act responsibly towards their communities, they encourage greater citizen participation and empowerment (Vigoda 2002). Engaged and empowered communities are better able to contribute to resilience-building efforts, by offering local knowledge, resources, and innovative solutions. Active participation ensures that resilience strategies are community-driven and contextually relevant.

Considering all the points discussed thus far, we can conclude that SRLPA initiatives undertaken by municipalities can significantly enhance territorial resilience. Economically, municipal SRPLA practices such as promoting local businesses, investing in infrastructure, and fostering job creation can bolster local economies, thereby strengthening the economic aspect of territorial resilience. Socially, SRLPA activities focusing on community engagement, providing social services, and promoting inclusive policies can build social cohesion and capacity, essential for a resilient territory to withstand and recover from various challenges. Furthermore, environmental SRLPA efforts, such as implementing sustainable development policies, promoting renewable energy, and enhancing green spaces, directly align with the environmental aspect of territorial resilience, mitigating risks posed by climate change and natural disasters. By integrating SRLPA principles into their governance and operations, municipalities can proactively contribute to territorial resilience by fostering economic stability, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability, ultimately supporting the overall well-being and adaptability of communities in the face of adversity.

Some studies suggest that social responsibility at the regional level enhances territorial resilience by promoting community resilience, shared governance and sustainable development (Rela et al. 2020), and effective public–private networks (Del Baldo 2017). For instance, Yang and Wang’s (2024) study examines and verifies that urban resilience has improved from 2005 to 2021 in China. The study’s findings provide valuable insights for policymakers by identifying the best- and worst-performing provinces in terms of urban resilience, allowing them to learn from successful strategies and address weaknesses in underperforming regions. In Spain, García-Fernández and Peek (2023) emphasize the transition towards smart regions and the importance of digitalization, social innovation, and climate change adaptation in rural communities. This study advocates for smart development in rural areas as it can bridge the gap between rural and urban realities by leveraging technology, innovation, and community engagement to create more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient territories.

To summarize, the SRLPA impacts citizens’ connection, attraction, and identification of the municipalities, increasing citizens’ participation. Similarly, analyzing the social responsibility of municipalities within a particular territory will aid decision-making in favor of resilience.

2.3. SRLPA and Citizen Participation

Recent studies suggest a strong link between sustainable regional development and citizen participation, highlighting its role in decision-making, technology assessment, inclusive governance, and resilience planning (Bouzguenda et al. 2019; Matamanda and Chinozvina 2020; Weinberger et al. 2021). Constantinescu et al. (2019) argue that increased citizen participation in decision-making can generate better public policy outcomes and positively impact citizens’ quality of life.

Building on Canyelles’ (2011) theoretical approach to the SRPA, the following outlines the actions expected from a responsible public administration:

- -

- Strong values and improved governance: Social responsibility must be an integral part of public entity management, embodied through strong values enshrined in codes of ethics or conduct. These codes define the principles guiding their behavior and outline the tools for ensuring compliance with these values. Therefore, Canyelles (2011) argues that SRPA management should be formalized. Enhanced public governance enables the public sector to better address the challenges of meeting the needs of citizens, public employees, and all stakeholders. To achieve this, trust must be built through promoting dialogue and authenticity. Just as good governance is demanded from the private sector, the public sector must also adhere to high governance standards. Territorial resilience, cultivated through responsible strategies, promotes shared governance and sustainable development among local actors.

- -

- Efficiency of public policies: Public administrations’ primary responsibility to society is to achieve positive results and sustainable impacts within their scope of action (Sisto et al. 2020). This is crucial for all organizations, including those in the public sector, despite not competing in the market. For public entities to generate significant impacts, be efficient, and address the concerns of citizens, they require a more specialized and close-knit management approach. This means having a functional organization where teamwork is predominant, and efforts are directed towards current preferences.

- -

- Transparency: Just as the private sector is required to disclose information, public administration must go beyond mere accountability (Greiling and Spraul 2010; Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al. 2023). It should not only adhere to ethical values, principles of sustainability, transparency, and social responsibility but also determine how to exercise its power. Specifically, it must establish the mechanisms by which citizens participate in decision-making processes and ensure that these decisions are made in alignment with the public interest (Armstrong 2005; Fung 2006, 2015; Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen 2018; Chan et al. 2022).

- -

- Legitimacy: For public administrations to achieve the necessary presumed legitimacy (Olsen 2004), they must focus not only on implementing good environmental and labor practices and acting transparently before the citizenry but also on creating public value. Legitimacy is primarily attained through the trust of citizens and, most importantly, through the administration’s ability to understand and address the problems faced by the public (Kettl 2015; Scherer et al. 2013; Moura and Miller 2019; Elston 2024).

- -

- Economic issues, environment, and socio-labor concerns: Public administrations, like businesses, must aim to create economic, environmental, and social value, enhancing the common welfare of both present and future generations (WCED 1987; Silva et al. 2023a). Economically, this can be exemplified by promoting local procurement or reducing the time required to pay suppliers, as well as shortening the time needed to process administrative permits (Eckersley et al. 2023). Environmentally, this includes the use of clean energy. Many municipalities are already making environmental improvements through Agenda 21, which serves as a benchmark for local commitment to sustainability (Bisogno et al. 2023). Socially, this encompasses human rights, health and safety, non-discrimination, equality, integration, and work–life balance. In this regard, equality and work–life balance policies are the most frequently implemented by public administration.

Despite the wide range of actions that social responsibility entails in public administrations, they tend to focus on very specific aspects, such as social clauses, ethical codes, and the publication of sustainability reports. The inclusion of social clauses in public administration actions provides several advantages to the administration itself, the citizenry, and the territory. These include increased legitimacy of the administration and an improved quality of life in the territory. In public procurement, applicable social criteria refer to the quality of working conditions, social inclusion, environmental sustainability, ethical management of organizations, and territorial solidarity, thereby promoting social responsibility among their contractors.

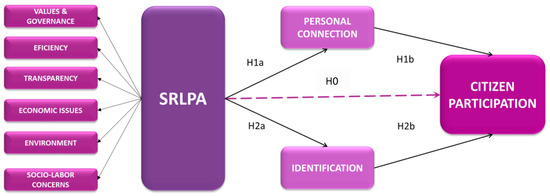

The need for resilient territories is inherent to the current environmental, social, and governance (ESG) discourse and essentially includes balanced economic, social, and environmental development and a commitment to democratic processes and participatory governance (Yeh 2017). ESG considerations have become a significant priority for governments globally. Local governments, in particular, face heightened responsibilities, as they are directly involved in the execution of numerous ESG-related initiatives (Armstrong and Li 2022). Within the framework of the SRLPA, the responses to challenges such as climate change, community engagement, and the evolution of governmental structures, systems, and organizational cultures demonstrate the practical application of ESG principles at the local level. However, even if a municipality strives to improve the local government’s social responsibility—its SRLPA—(Bisogno et al. 2023; García-Fernández and Peek 2023) it is difficult to imagine that this could have a direct impact on citizens’ participation in general and on issues that strengthen the resilience of the territory, in particular. In fact, a key aspect of the widely debated crisis in representative democracy today is the perceived gap between policymakers and citizens (Koskimaa and Rapeli 2020). Vigoda (2002) and other authors (e.g., Hronec et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2022) point out that modern societies are witnessing an increase in citizen passivity, with many opting for the comfort of consumerism rather than engaging in the effort and challenges of active participation. The following hypothesis is presented in negative terms:

H0.

Policymakers cannot expect a direct relationship between the SRLPA and citizen participation.

On the contrary, it seems necessary for other variables to come into play and serve as a bridge or link between the citizens’ perception of the local government’s social responsibility and their active participation in the territory as an expression of real democracy (Michels and De Graaf 2010; Sánchez-Hernández et al. 2020; Hendriks and Dzur 2021).

In this context, the personal connection of citizens with the Municipality Council could be considered a good mediator. In the context of public administration, the relationship between residents and municipal officials is crucial for fostering trust, satisfaction, and a sense of community (Bruning et al. 2004; Lovari et al. 2012; Romero-Subia et al. 2022). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a.

There is a direct and positive relationship between the SRLPA and the personal connection of citizens with the Municipal Council.

H1b.

There is a direct and positive relationship between the personal connection of citizens with the Municipal Council and its participation.

Another variable to be considered is how citizens perceive their connection and alignment with the Municipal Council. There is a line of research in the social sciences to evaluate the connection of individuals with an organization. This concept is directly applicable to public administration, where citizen identification with their Municipal Council can influence civic engagement, trust in local government, and community cohesion (Andrews et al. 2008; Kiss et al. 2022), citizens’ participation being the consequence (Bartoletti and Faccioli 2016; Bhagavathula et al. 2021). Based on these last considerations, we present the following hypotheses:

H2a.

There is a direct and positive relationship between the SRLPA and the identification of citizens with the Municipal Council.

H2b.

There is a direct and positive relationship between the identification of citizens with the Municipal Council and its participation.

The theoretical model that emerges from the above is represented in Figure 1 as follows.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model.

3. Materials and Methods

This study, which aims to find the causal relationships proposed in the presented theoretical model, has used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Partial Least Squares (PLS). PLS-SEM is a non-parametric method that allows for the estimation of complex cause–effect relationship models by combining path analysis with latent variable modeling. Unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM does not require strict assumptions about data distribution and can handle small sample sizes and non-normal data. This makes it particularly suitable for exploratory research or when the primary goal is prediction rather than theory testing. The method uses an iterative algorithm to maximize the explained variance of dependent variables, making it robust in handling complex models with multiple indicators and constructs (Akter et al. 2017; Hair et al. 2019).

The SmartPLS software has been used, subject to subscription and authorization by its authors (SmartPLS GmbH 2024). This software bases the parameter estimates on the ability to minimize the residual variances of the endogenous variables by maximizing the explained variance (R2) of the dependent variables. In this way, the main objective of this technique, which is to predict the dependent variables (latent or manifest), is achieved. The data are primary, obtained from a questionnaire focused on the constructs of this study: the SRLPA, the personal connection with the Municipal Council, the Identification with the Municipal Council, and citizen participation.

The scales have been developed based on previous works (Appendix A). Starting with the scale for approaching the SRLPA, the following items have been extracted from the theoretical work of Canyelles (2011).

It is common practice in the social sciences to develop, validate, and subsequently use measurement scales for research purposes, such as in the field of marketing (Bruner et al. 2005). However, Organizational Science research often adapts scales developed in marketing for its own objectives (Heggestad et al. 2019). In this study, to measure the variable personal connection with the Municipal Council in the context of public administration, the scale adapted from Gremler and Gwinner (2000) was employed. Originally, the authors developed the scale to assess customer–employee rapport in service relationships. Given the similarities between interpersonal interactions in customer service and those in municipal services, we consider that this scale provides a robust framework for evaluating personal connections within a municipal context. Gremler and Gwinner’s scale measures the quality of interpersonal relationships and the rapport between customers and employees, which are critical components of effective service delivery. By adapting this scale, this study leverages a validated instrument to measure the depth and quality of these interactions within a municipal setting, ensuring the reliability and validity of the measurement.

To measure the variable Municipal Council–citizen identification, the scale adapted from Mael and Ashforth (1992) has been employed. Mael and Ashforth developed this scale to assess organizational identification, particularly how alumni identify with their alma mater. Acknowledging the parallels between organizational identification and citizens’ identification with their Municipal Council, this scale offers a validated approach to measuring the extent to which citizens align themselves with their local government. By adapting this scale, this study ensures that the measurement captures the strength of citizens’ identification with their Municipal Council, providing reliable and valid data for analysis.

Finally, to measure the variable citizen participation, this study employs a scale adapted from Yoon et al. (2004). This scale measures the degree of customer involvement through feedback, suggestions, and reporting issues. These behaviors are critical in a public administration context where citizen participation is essential for improving municipal services, enhancing governance, and fostering community engagement. By adapting this scale, this study leverages a validated instrument to measure various dimensions of citizen participation, ensuring reliability and validity in capturing how citizens interact with and contribute to their local government. The adapted scale includes items that reflect typical forms of citizen participation.

The data were collected by a team of surveyors who visited various localities in Extremadura in May 2024. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis and were invited to complete the survey either electronically or on paper, according to their preference. The survey was designed to be completed in less than 10 min. Participants were informed about the purpose of this study and gave their consent for their responses to be used in statistical analysis, with their anonymity guaranteed. Finally, the sample of this study was created by 669 citizens from 18 different Municipal Councils in the region of Extremadura, Spain, who answered a self-administered questionnaire. In accordance with ethical guidelines, all respondents in this study were volunteers who provided informed consent to participate. This study adhered to the principles of the open science movement, and as such, the data collected during the research are available upon request for verification and further analysis

Although some authors have indicated that the rural development in the region is not sustainable enough (Maldonado-Briegas and Sánchez-Hernández 2019; Naranjo-Molina et al. 2021), recently, the Autonomous Region of Extremadura has been experiencing greater awareness of community resilience. Different aspects of economic, social, human, and natural capital promote resilient territorial dynamics in the region (Cárdenas Alonso and Nieto Masot 2017; Candelario-Moreno and Sánchez-Hernández 2024). For instance, authors such as Gurría Gascón and Nieto Masot (2020) highlight the polycentric system of towns in Extremadura and how this good distribution is helping to stabilize the population as a viable alternative to the demographic challenge. In the same line, Gómez-Ullate et al. (2020) put the focus on how cultural heritage and cultural tourism can act as resilience factors in the region.

4. Results

Although PLS-SEM does not require normally distributed data and does not imply meeting homoscedasticity assumptions, Table 1 provides a summary of key descriptive statistics for the variables in this study and includes robustness checks as recommended by Vaithilingam et al. (2024). First, values of skewness and kurtosis are outside the range of −1 to 1. Second, Cramér–Von Mises’s test, an empirical distribution function omnibus test, confirms the composite hypothesis of normality.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between the variables. Each cell represents the degree of linear relationship between two variables, showing positive values and significance at the 0.01 level. Table 1 and Table 2 collectively provide a detailed overview of the distributional characteristics and interrelationships of the variables, forming the basis for further statistical analysis.

Table 2.

Correlations.

In the framework of this study, the first construct of the model—the SRLPA—is conceptualized as a second-order construct with six dimensions, as grounded in the theoretical background. A second-order construct, in simple terms, is an overarching construct that is measured by multiple underlying dimensions. Each of these dimensions, in turn, is assessed by its own set of variables (indicators). When a construct is considered second-order, the dimensions themselves become the indicators of the higher-level construct, effectively aggregating the information from the original indicators of each dimension to provide a comprehensive measure of the overall construct (Sarstedt et al. 2019).

The descriptive statistics of the specific constructs of this study (Table 3) reveal key insights into the perceptions of the SRLPA and related variables among the respondents. On a scale from 0 to 10, the SRLPA received an average score of 4.81, indicating a moderate level of perceived social responsibility by local governments. This is accompanied by a standard deviation of 2.36, suggesting variability in respondents’ views. The variables personal connection and identification with the SRLPA exhibited similar average scores of 4.59 and 4.77, respectively, both with slightly higher variability, particularly in personal connection, which had a standard deviation of 2.59. Interestingly, citizen participation was rated slightly higher, with an average of 5.17, reflecting a somewhat stronger perception of citizen engagement in local governance. The consistency in standard deviations across these variables highlights a moderate to substantial diversity in individual perceptions across all measured aspects.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the constructs.

After establishing this consideration, the main results from both the measurement model and the structural model are presented. The measurement model results illustrate the reliability and validity of the constructs, ensuring that the second-order construct and its dimensions are accurately measured. The structural model results then demonstrate the relationships between the constructs, highlighting the significance and strength of these relationships within the theoretical framework. This dual analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the model’s overall performance and its alignment with the theoretical background.

4.1. Evaluating the Measurement Model

This section addresses the assessment of the scales’ validity and the reliability of the measurement model (the inner model). Our aim is to determine whether the theoretical constructs are accurately represented by the observed variables. This evaluation focuses on two key attributes: validity, which assesses whether we are measuring what we intend to measure, and reliability, which examines the stability and consistency of the measurement process. To achieve this, we have calculated the reliability of individual items, the internal consistency or reliability of the scales, and analyzed the average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in Table 4 (Nunally and Bernstein 1978; Falk and Miller 1992).

Table 4.

Measurement model.

The most stringent criterion for an indicator to be accepted as part of a construct is having a loading greater than 0.7, indicating that the shared variance between the construct and its indicators exceeds the error variance. In our analysis, all items met the criterion for individual reliability, so no items were removed from the initial model. The internal consistency of the constructs was verified, with Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of 0.79 or exceeding this value and composite reliability indicators above the 0.7 threshold, indicating satisfactory reliability. Convergent validity was confirmed, with the AVE consistently above 0.5, suggesting that the constructs explained more variance than was left unexplained. It is especially remarkable the value of 0.824 for the SRLPA.

The discriminant validity of the latent variables was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Fornell and Larcker 1981), and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) test, satisfactory for each pair of factors were <0.90 (Henseler et al. 2015) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Discriminant validity.

4.2. Evaluating the Structural Model

In the evaluation of the structural model, bootstrapping was employed to assess the significance of path coefficients. This non-parametric resampling technique generates multiple subsamples from the original data set, allowing for the estimation of standard errors and confidence intervals for the model parameters. By doing so, bootstrapping provides robust statistical inference, ensuring that the results are not dependent on the assumption of normality. This method is widely recognized for its effectiveness in validating the structural model within the context of PLS analysis, thus enhancing the reliability and validity of the findings. In addition, model fit indicators (Henseler et al. 2015) have been calculated. Table 6 and Table 7 show the results obtained.

Table 6.

Hypotheses testing.

Table 7.

Model fit indicators.

5. Discussion

The measurement model has yielded excellent results, confirming the SRLPA as a second-order construct with its six dimensions intact. Additionally, all items considered in the other variables were retained, validating the theoretical framework with empirical evidence.

Regarding the structural model, the null hypothesis (H0) posited no direct impact of the independent variable (SRLPA) on the dependent variable (citizen participation). The analysis revealed a p-value higher than 0.05 for the direct relationship between the SRLPA and citizen participation, indicating that there is evidence to reject the direct relationship and therefore support the null hypothesis. However, both Hypotheses 1 (H1a and H1b) and 2 (H2a and H2b) have been supported by the analysis, confirming that the impact of the SRLPA on citizen participation exists, but it is indirect. This indirect effect operates through other mediating variables, which warrant the attention of policymakers to fully understand and leverage the pathways through which the SRLPA influences citizen participation.

The predictive power of the model is demonstrated by Q2 (0.339 > 0) and the adjusted R² value obtained of 0.558, indicating that the model explains approximately 56% of the variability in the dependent variable, citizen participation. This substantial proportion of explained variance highlights the significant influence of the interaction among the independent variables, namely the SRLPA, personal connection, and identification. These findings underscore the robustness of the model in capturing the complex dynamics and interplay between these variables and their collective impact on citizen participation.

The results obtained have significant implications, reflecting the innovative aspects of this study. The scales used in this research were carefully adapted to fit this study’s specific context. The scale SRLPA is derived from a theoretical framework, representing a significant contribution to the field. Additionally, the other scales, originally from the field of marketing, were adapted for application in public administration studies, which is another notable contribution of this work. The reliability and validity of these adapted scales have been empirically analyzed and confirmed through the case study of Extremadura, ensuring their robustness and applicability. Indeed, Extremadura exemplifies resilience through its adaptive strategies to economic, social, and environmental challenges, driven by social responsibility efforts. This makes Extremadura a representative case that supports this study’s findings on resilience. Less developed regions in Europe, such as Extremadura in Spain, aware of social responsibility could indeed be considered typical cases of resilient territories. By including Extremadura, this study effectively highlights how resilience manifests in less developed regions, reinforcing the generalizability of the results.

Specific suggestions can be made on how local governments can improve interactions with citizens, enhance transparency, and boost public engagement. For instance, local governments can adopt open data initiatives and develop and maintain user-friendly digital platforms, such as websites and mobile apps, where citizens can easily access information, submit feedback, and participate in decision-making processes. By providing detailed up-to-date information, and making platforms interactive and accessible, governments can enhance SRLPA and foster a more engaged and resilient community.

6. Conclusions

Based on the idea that territorial social responsibility, cultivated through CSR strategies, promotes shared governance and sustainable development among local actors (Rela et al. 2020), this study focuses on the SRLPA and its indirect impact on citizen participation.

It has been exposed that under the lens of the Institutional theory, the SRLPA cannot be taken for granted (Green et al. 2009). At its core, the theory emphasizes the importance of legitimacy, where public organizations must conform to societal norms and expectations to gain acceptance. Consequently, the SRLPA should be put into practice and fostered through better regulation, stakeholder dialogues, historical and political determinants, and social mechanisms.

With this empirical study, we contribute to the field by defending that institutionalizing social responsibility at the local level creates positive feedback loops that reinforce resilience. When social responsibility is embedded within the institutional framework, it creates a path dependency where future actions and policies are influenced by this established norm. This institutionalization leads to continuous improvement and adaptation, reinforcing resilience over time. Positive feedback loops ensure that socially responsible practices become the standard, leading to sustainable regional development.

An important contribution of this article is the adaptation of theoretical content, particularly the arguments of Canyelles (2011), originally published in Spanish, for measuring the SRLPA. The scale, now available in English, provides researchers with a valuable tool for conducting further studies and gaining deeper insights into the topic.

Additionally, this study investigates the strength of citizens’ identification with their Municipal Council and the degree of their identification with the institution, using these factors as instrumental mediator variables. This constitutes the second significant contribution of this work. It has been empirically demonstrated that the relationship between the SRLPA and citizen participation is not direct; rather, the SRLPA exerts its influence through two mediating variables: citizen connection with the municipality and the perceived bond with the local government. This understanding contributes insights into how such identification impacts civic behavior and attitudes toward local governance. The findings suggest that for the SRLPA to positively impact citizen participation, it is imperative to strengthen relationships with citizens, thereby enhancing their engagement in municipal affairs. Undoubtedly, other variables could mediate the relationship between the SRLPA and citizen participation to build resilient communities that are stronger and better prepared for unpredictable futures.

To sum up, contributing to an incipient field of research, this work goes ahead developing a scale for approaching the SRLPA and demonstrating its indirect impact on citizen participation. The results show that efforts to improve values and governance, efficiency, transparency, and the triple bottom line alone are insufficient to significantly strengthen citizens’ trust. Instead, other efforts are needed from Municipal Councils, likely more subtle ones, such as improving communication with citizens, fostering a sense of belonging, or reinforcing neighborhood-specific public policies in the future.

Some practical implications derive from this study. Firstly, and related to policy formulation, it is recommended the development of policies that embed social responsibility into the core functions of local administrations, ensuring that resilience and sustainable development are prioritized. Secondly, it is necessary to invest in training and resources to enhance the capacity of local administrations to act responsibly and effectively. Thirdly, local administrations should consider the implementation of robust mechanisms to monitor and evaluate social responsibility initiatives, ensuring accountability and continuous improvement. Finally, it is highly recommended to foster community engagement. Local administrations must reinforce citizen participation, build trust, gather input, and ensure that resilience strategies are inclusive and representative.

These new avenues for research highlight the limitations of this study, which has considered only two mediator variables. Specifically, our focus on the SRLPA and the selected mediator variables may not capture all the possible factors influencing citizen participation. Additionally, our data collection was limited to specific localities in Extremadura, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. This study must be tested in other contexts with new potential explanatory variables to enhance its applicability. The scales developed and the theoretical model proposed and empirically validated will contribute to advancements in this field of research and assist policymakers in measuring the actions of Municipal Councils. Furthermore, they will help redirect efforts to foster the necessary citizen participation for building resilient territories.

The research conducted in Extremadura serves as a robust case study, offering valuable insights that can be adapted and replicated in other regions. Moreover, to enhance the generalizability and depth of future investigations, we recommend broadening the scope by incorporating a more diverse set of variables, expanding the geographical context, and utilizing longitudinal research designs. Such approaches would facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the causal relationships between the SRLPA, intermediary variables, and citizen participation, ultimately contributing to a richer body of knowledge in this field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura suggests to use an Informed Consent Form. The interviewee was informed at the beginning of the questionnaire and consented to proceed with the statement: I agree to participate in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Scales

- ❖

- SRLPA—Adapted from Canyelles (2011).

- -

- Values and Good Governance

- VG1: I feel that the Municipal Council, in addition to governing the municipality well, is concerned about social issues.

- VG2: I see that the Municipal Council is concerned with being transparent in the use of public resources.

- VG3: I believe that the Municipal Council facilitates access to information about its management.

- -

- Efficiency

- EF1: I feel that the Municipal Council produces positive results in the municipality.

- EF2: It seems to me that the Municipal Council has the capacity to plan, produce, measure, and evaluate the impact of its actions in the medium and long term.

- EF3: I believe that the Municipal Council ensures institutional and interdepartmental cooperation when necessary and focuses its efforts on key aspects.

- -

- Transparency

- T1: The Municipal Council informs and gathers the opinions of the residents.

- T2: The Municipal Council seeks consensus in its decisions.

- T3: The Municipal Council is in favor of participatory budgets, public hearings, and participatory local policies.

- -

- Economic Issues

- E1: The Municipal Council is an important contractor of services in the municipality (local purchases/payments to suppliers), promoting local development.

- E2: The Municipal Council facilitates the location and development of businesses in the municipality.

- -

- Environment

- EM1: The Municipal Council is a good example of an institution that protects the environment, reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions.

- -

- Socio-labor Concerns

- SL1: The Municipal Council is a good example of hiring people with disabilities, gender equality, work-life balance, or job stability.

- SL2: I feel that the Municipal Council is guided by values of ethics, democratic culture, innovation, and a service-oriented attitude towards citizens.

- SL3: I think the Municipal Council works hard for the municipality to become a socially and economically developed, inclusive, and sustainable territory.

- ❖

- Personal Connection with the Municipal Council—Adapted from Gremler and Gwinner (2000).

- PC1: When I need something, I like to be attended to by the people at the front of the Municipal Council.

- PC2: I take great care in my interactions with the people at the Municipal Council.

- PC3: I feel that there is a bond between the people at the Municipal Council and myself.

- ❖

- Identification with the Municipal Council—Adapted from Mael and Ashforth (1992).

- ID1: When someone criticizes the Municipal Council, I take it as an insult.

- ID2: I care about what people think about the Municipal Council.

- ID3: When the Municipal Council achieves something and is successful, I feel that the success is also mine.

- ID4: If there is news in the press, radio, or TV that criticizes the Municipal Council, I do not feel well.

- ❖

- Citizen Participation in the Municipal Council—Adapted from Yoon et al. (2004).

- PART1: When I receive excellent service at the Municipal Council, I like to let them know so they are aware.

- PART2: I make suggestions at the Municipal Council to improve the service they provide.

- PART3: If I see something that doesn’t work in the municipality or any fault of the Municipal Council, I let them know so they can resolve it as soon as possible.

References

- Ahn, Se-Yeon, and Dond-Jun Park. 2018. Corporate social responsibility and corporate longevity: The mediating role of social capital and moral legitimacy in Korea. Journal of Business Ethics 150: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, Shahriar, Samuel Fosso Wamba, and Saifullah Dewan. 2017. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Production Planning & Control 28: 1011–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldunce, Paulina, Ruth Beilin, John Handmer, and Mark Howden. 2016. Stakeholder participation in building resilience to disasters in a changing climate. Environmental Hazards 15: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, Kenneth, Emmanuel Adegbite, and Tazeeb Rajwani. 2016. Corporate social responsibility in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts: Do institutional voids matter? Journal of Business Ethics Rajwani 134: 135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Rhys, Richard Cowell, James Downe, Steve Martin, and Davidk Turner. 2008. Supporting effective citizenship in local government: Engaging, educating and empowering local citizens. Local Government Studies 34: 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Anona, and Yonggiang Li. 2022. Governance and Sustainability in Local Government. Business and Finance Journal Australasian Accounting 16: 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Elia. 2005. Integrity, transparency and accountability in public administration: Recent trends, regional and international developments and emerging issues. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti, Roberta, and Franca Faccioli. 2016. Public engagement, local policies, and citizens’ participation: An italian case study of civic collaboration. Social Media + Society 2: 2056305116662187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, Bernardino, María Dolores Guillamón, and Ana María Ríos. 2023. What factors make a municipality more involved in meeting the sustainable development goals? Empirical evidence. Environment Development and Sustainability. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Robert Jonh, Crispian Fuller, and Mark J. Ramsden. 2004. Local government and local economic development in Britain: An evaluation of developments under labour. Progress in Planning 62: 209–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavathula, Susila, Katja Brundiers, Michael Stauffacher, and Braden Kay. 2021. Fostering collaboration in city governments’ sustainability, emergency management and resilience work through competency-based capacity building. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 63: 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bice, Sara. 2017. Corporate social responsibility as institution: A social mechanisms framework. Journal of Business Ethics 143: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogno, Marco, Beatriz Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Francesca Manes Rossi, and Noemi Peña-Miguel. 2023. Sustainable development goals in public administrations: Enabling conditions in local governments. International Review of Administrative Sciences 89: 1223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzguenda, Islam, Chaham Alalouch, and Nadia Fava. 2019. Towards smart sustainable cities: A review of the role digital citizen participation could play in advancing social sustainability. Sustainable Cities and Society 50: 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, Gordon C., Paul J. Hensel, and Karen E. James. 2005. Marketing Scales Handbook. Chicago: American Marketing Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bruning, Stephen D., Allison Langenhop, and Kimberly A. Green. 2004. Examining city–resident relationships: Linking community relations, relationship building activities, and satisfaction evaluations. Public Relations Review 30: 335–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Moreno, Cristina, and María Isabel Sánchez-Hernández. 2024. Redefining rural entrepreneurship: The impact of business ecosystems on the success of rural businesses in Extremadura, Spain. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation 20: 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, Josep María. 2011. Responsabilidad social de las administraciones públicas. Revista de Contabilidad y Dirección 13: 77–104. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Cárcaba, Ana, Eduardo González, and Rubén Arrondo. 2023. Effects of the political configuration of local governments on subjective well-being. Policy Studies, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Alonso, Gema, and Ana Nieto Masot. 2017. Towards Rural Sustainable Development? Contributions of the EAFRD 2007–2013 in Low Demographic Density Territories: The Case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Sustainability 9: 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Vivian L., and Ehsan H. Feroz. 2001. Institutional theory and accounting rule choice: An analysis of four US state governments’ decisions to adopt generally accepted accounting principles. Accounting, Organizations and Society 26: 565–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Yolande E., Rashmi Krishnamurthy, Janelle Mann, and Rajiv Sabherwal. 2022. Public participation in policy making: Evidence from a citizen advisory panel. Public Performance & Management Review 45: 1308–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Mingxing, Liangkan Chen, Jiafan Cheng, and Jianhui Yu. 2022. Identifying interlinkages between urbanization and Sustainable Development Goals. Geography and Sustainability 3: 339–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Iris H.-Y. 2018. An institutional theory of corporate regulation. Current Legal Problems 71: 279–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, Mihaela, Andreea Orîndaru, Stefan-Claudiu Căescu, and Andreea Pachițanu. 2019. Sustainable Development of Urban Green Areas for Quality of Life Improvement—Argument for Increased Citizen Participation. Sustainability 18: 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Beatriz, Ana María Ríos, and María Dolores Guillamón. 2023. Transparency in public administrations: A structured literature review. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 35: 537–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Robert, Pamela Tolbert, and Johnny Boghossian. 2019. Institutional Theory in Organization Studies. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management Boghossian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, Mara. 2017. Corporate Social Responsibility, Shared Territorial Governance and Social Innovation: Some Exemplary Italian Paths. In Dimensional Corporate Governance. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Cham: Springer, pp. 103–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudchenko, Valentina, and Konstantin Vitman. 2018. Public administration of economic development in the context of the institutional theory. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies 4: 139–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, Peter, Anthony Flynn, Katarzyna Lakoma, and Laurence Ferry. 2023. Public procurement as a policy tool: The territorial dimension. Regional Studies 57: 2087–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 1998. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environmental Quality Management 8: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, Thomas. 2024. Efficiency, legitimacy, and reform. In Understanding and Improving Public Management Reforms. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R. Frank, and Nancy B. Miller. 1992. A Primer for Soft Modeling. Akron: University of Akron Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feindt, Peter H., and Angela Oels. 2005. Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 7: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, Paul, and Sara Gustafsson. 2017. Moving from high-level words to local action—Governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 26: 129–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 34: 161–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Archon. 2006. Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review 66: 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Archon. 2015. Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review 75: 513–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, Dolores, and José Antonio Folgado-Fernández. 2020. Regional economic sustainability: Universities’ role in their territories. Land 9: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, Cristina, and Daniël Peek. 2023. Connecting the Smart Village: A Switch towards Smart and Sustainable Rural-Urban Linkages in Spain. Land 12: 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel María, José Valeriano Frías-Aceituno, and Luís Rodríguez-Domínguez. 2013. Determinants of corporate social disclosure in Spanish local governments. Journal of Cleaner Production 39: 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascó, Mila. 2003. New technologies and institutional change in public administration. Social Science Computer Review 21: 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ullate, Martín, Laurent Rieutort, Afroditi Kamara, Ana Sofía Santos, Antonio Pirra, and Merly Gotay Solís. 2020. Demographic challenges in rural Europe and cases of resilience based on cultural heritage management. A comparative analysis in Mediterranean countries inner regions. European Countryside 12: 408–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, Almudena, Manuel Collares-Pereira, Francisco J. Cuadros, and Tomás Fartaria. 2014. Energy self-sufficiency through hybridization of biogas and photovoltaic solar energy: An application for an Iberian pig slaughterhouse. Journal of Cleaner Production 65: 318–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ramiro, Abel, Gil Gonçalves, Alonso Sánchez-Ríos, and Jin Su Jeong. 2016. Using a VGI and GIS-based multicriteria approach for assessing the potential of rural tourism in Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 8: 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Sandy Edward, Jr., Yuan Li, and Nitin Nohria. 2009. Suspended in self-spun webs of significance: A rhetorical model of institutionalization and institutionally embedded agency. Academy of Management Journal 52: 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiling, Dorathea, and Katharina Spraul. 2010. Accountability and the challenges of information disclosure. Public Administration Quarterly 34: 338–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gremler, Dwayne D., and Kevin P. Gwinner. 2000. Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. Journal of Service Research 3: 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurría Gascón, José Luís, and Ana Nieto Masot. 2020. Rururban partnerships: Urban accessibility and its influence on the stabilization of the population in rural territories (Extremadura, Spain). Land 9: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian. M. Ringle. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Seungmin, and Kiyohiko Ito. 2023. What explains the spread of corporate social responsibility? The role of competitive pressure and institutional isomorphism in the diffusion of voluntary adoption. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, Nathalie, Sorin Dan, and Ines Mergel. 2024. Digitally-induced change in the public sector: A systematic review and research agenda. Public Management Review 26: 1963–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggestad, Eric D., David J. Scheaf, George C. Banks, Mary Monroe Hausfeld, Scott Tonidandel, and Eleanor B. Williams. 2019. Scale adaptation in organizational science research: A review and best-practice recommendations. Journal of Management 45: 2596–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Carolyn, and Albert Dzur. 2021. Citizens’ Governance Spaces: Democratic Action Through Disruptive Collective Problem-Solving. Political Studies 70: 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jórg, Christian. M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horeczki, Réka, and Ilona Pálné Kovács. 2023. Governance challenges of resilient local development in peripheral regions. In Resilience and Regional Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J. Brian. 2018. Community resilience and communication: Dynamic interconnections between and among individuals, families, and organizations. Journal of Applied Communication Research 46: 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronec, Martin, Janka Beresecká, and Štefan Hronec. 2022. Social Responsibility in Local Government. Prague: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Jin Su, and Álvaro Ramírez-Gómez. 2018. Optimizing the location of a biomass plant with a fuzzy-DEcision-MAking Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (F-DEMATEL) and multi-criteria spatial decision assessment for renewable energy management and long-term sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 182: 509–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettl, Donald F. 2015. The Transformation of Governance: Public Administration for the Twenty-First Century. Baltimore: Jhu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Bernadett, Filka Sekulova, Kathrin Hörschelmann, Carl F. Salk, Wakana Takahashi, and Christine Wamsler. 2022. Citizen participation in the governance of nature-based solutions. Environmental Policy and Governance 32: 247–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskimaa, Vesa, and Lauri Rapeli. 2020. Fit to govern? Comparing citizen and policymaker perceptions of deliberative democratic innovations. Policy and Politics 48: 637–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Thomas B., and Masoud Shadnam. 2008. Institutional theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication (Volume V). Edited by Donsbach Wolfgang. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 2288–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Eungkyoon. 2011. Information, interest intermediaries, and regulatory compliance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 137–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2023. Democracy’s surprising resilience. Journal of Democracy 34: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LopezDeAsiain, María, and Vicente Díaz-García. 2020. The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes. Sustainability 12: 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovari, Alessandro, Valentina Martino, and Jeong-Nam Kim. 2012. Citizens’ Relationships with a Municipality and Their Communicative Behaviors in Negative Civic Issues. International Journal of Strategic Communication 6: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, Paulo M., Mário Vale, and Julián Mora-Aliseda. 2021. Smart specialisation strategies and regional convergence: Spanish Extremadura after a period of divergence. Economies 9: 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, Fred, and Blake E. Ashforth. 1992. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 13: 103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, Sachit, Carina I. Hausladen, Javier Argota Sánchez-Vaquerizo, Marcin Korecki, and Dirk Helbing. 2022. Participatory resilience: Surviving, recovering and improving together. Sustainable Cities and Society 83: 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Briegas, Juan José, and María Isabel Sánchez-Hernández. 2019. Regional public policy fostering entrepreneurship through the educational system: Evidence from the autonomous community of Extremadura in Spain. In New Paths of Entrepreneurship Development: The Role of Education, Smart Cities, and Social Factors. Cham: Springer, pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Azúa, Beatriz C., and Felipe Martín-Vegas. 2019. Characteristics of Extremaduran agri-food companies according to innovation strategies. Technology Transfer and Entrepreneurship 6: 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamanda, Abraham, and Queen Chinozvina. 2020. Driving Forces of Citizen Participation in Urban Development Practice in Harare, Zimbabwe. Land Use Policy 99: 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mättö, Toni, Jenna Anttonen, Marko Järvenpää, and Antti Rautiainen. 2020. Legitimacy and relevance of a performance measurement system in a Finnish public-sector case. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 17: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, Sara, Joshua P. Newell, and Melissa Stults. 2016. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning 147: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, Oliver, and Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués. 2021. Corruption consolidation in local governments: A grounded analytical framework. Public Administration 99: 530–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, Ank. 2011. Innovations in democratic governance: How does citizen participation contribute to a better democracy? International Review of Administrative Sciences 77: 275–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, Ank, and Laurens De Graaf. 2010. Examining Citizen Participation: Local Participatory Policy Making and Democracy. Local Government Studies 36: 477–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, David P., and Hugh T. Miller. 2019. On legitimacy: Is public administration stigmatized? Administration & Society 51: 770–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Molina, Fernando, Eva Carrapiso-Luceño, and María Isabel Sánchez-Hernández. 2021. The Fourth Sector and the 2030 Strategy on Green and Circular Economy in the Region of Extremadura. In Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Fourth Sector: Sustainable Best-Practices from across the World. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 283–97. [Google Scholar]

- Navinés, Ferran, José Pérez-Montiel, Carles Manera, and Javier Franconetti. 2023. Ranking the Spanish regions according to their resilience capacity during 1965–2011. The Annals of Regional Science 71: 415–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, Ana, Gema Cárdenas Alonso, and Luís Manuel Costa Moreno. 2019. Principal component analysis of the leader approach (2007–2013) in South Western Europe (Extremadura and Alentejo). Sustainability 11: 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunally, Jum C., and Ira Bernstein. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, Antonio, and Jorge Olcina. 2022. Floods and Emergency Management: Elaboration of Integral Flood Maps Based on Emergency Calls Olcina, 12)—Episode of September 2019 (Vega Baja del Segura, Alicante, Spain). Water 15: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Christine. 1991. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review 16: 145–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Johan P. 2004. Citizens, public administration and the search for theoretical foundations. PS: Political Science & Politics 37: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, Federica, Mariangela Vita, and Pierluigi Properzi. 2019. Good Practices for the Management of Fragile Territories Resilience. TeMA: Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment 12: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porumbescu, Gregory A., and Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen. 2018. Linking decision-making procedures to decision acceptance and citizen voice: Evidence from two studies. The American Review of Public Administration 48: 902–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rela, Iskandar, Abd Hair Awang, Zaimah Ramli, Yani Taufik, Sarmila Sum, and Mahazan Muhammad. 2020. Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Community Resilience: Empirical Evidence in the Nickel Mining Industry in Southeast Sulawesi Muhammad, Indonesia. Sustainability 12: 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Paulo Jorge Gomes, and Luís Antonio Pena Jardim Gonçalves. 2019. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustainable Cities and Society 50: 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, Alessandra. 2018. Governance, Local Communities, and Citizens Participation. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Edited by Ali Farazmand. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riege, Andreas, and Nicholas Lindsay. 2006. Knowledge management in the public sector: Stakeholder partnerships in the public policy development. Journal of Knowledge Management 10: 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, Ana María, María Dolores Guillamón, Javier Cifuentes-Faura, and Bernardino Benito. 2022. Efficiency and sustainability in municipal social policies. Social Policy & Administration 56: 1103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, David, Laurence Vigneau, Stephan Bohn, and Christopher Wickert. 2023. Institutional theory-based research on corporate social responsibility: Bringing values back in. International Journal of Management Reviews 25: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Paolo, Paola Graziano, and Antonio Dallara. 2018. A capacity approach to territorial resilience: The case of European regions. The Annals of Regional Science 60: 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, Giulia, Lucio Masserini, and Ginevra Virginia Lombardi. 2021. Environmental performance of waste management: Impacts of corruption and public maladministration in Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production 288: 125521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Subia, José Fernando, Juan Antonio Jimber del Rio, María Salomé Ochoa-Rico, and Arnaldo Vergara-Romero. 2022. Analysis of Citizen Satisfaction in Municipal Services. Economies 10: 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, Miquel, and David Sancho. 2021. The role of local government in the drive for sustainable development public policies. An analytical framework based on institutional capacities. Sustainability 13: 5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]