Abstract

Frugality is an important psychological trait that is currently of interest as a research construct in a range of fields, from consumer behavior to financial literacy and financial well-being. Increasingly, the concept of frugality is also being linked to environmental responsibility and behavior, as the core of frugality is the reduction or minimization of resources used and consumed, an emphasis on the long-term use of purchased products, and an overall conservation of resources. For many years, researchers have used the Frugality Scale (FS), the specific research tool introduced to measure frugality in a standardized and valid way. The aim of the study was to examine the psychometric properties of FS translated into the Czech language, to evaluate the uni-dimensionality of the construct, and to analyze associations with relevant variables documenting respondents’ attitudes and behavior. For this purpose, the research based on face-to-face interviews among respondents representing the 15–74 years old population of Czechia was conducted. The obtained results showed that the previously developed FS achieved very good results in the Czech environment, where the obtained scores supported the hypothesized uni-dimensional structure of the scale. The CFA results show that the tested model fits well with empirical data. Convergent and construct validity is also shown to be high. Therefore, the Czech version of the Frugality Scale can be considered a reliable and valid instrument that is recommended for further use. By utilizing the FS, researchers and practitioners gain access to a robust tool for quantifying frugality and comprehending its pertinent aspects across diverse contexts.

1. Introduction

Consumer behavior research has traditionally focused on understanding the factors driving individuals’ choices and behaviors in the marketplace. Frugality has emerged as a prominent factor in recent years, representing a unique perspective on consumption characterized by deliberate and conscious efforts to reach a simple lifestyle, economize resources, and avoid unnecessary expenditures (Bove et al. 2009). It involves thoughtful and intentional management of resources, informed choices, prioritization of needs over wants, and finding satisfaction from non-material sources (Goldsmith et al. 2014).

Various discourses on frugality exist, including religious or worldview influences (Todd and Lawson 2003), historical perspectives (Witkowski 2010; Stearns 2001), values and morals (Belk 1988; Wilk 2001), and psychological factors, such as self-efficacy and self-control (Haws et al. 2012; Zavestoski 2002). However, this study follows the perspective of frugality as it was defined by Lastovicka et al. (1999), who perceived frugality as a consumer lifestyle trait encompassing restraint in acquiring economic goods and services and resourceful utilization of these resources to achieve long-term goals.

Scholars’ interest in frugal behavior has surged due to three significant factors. Firstly, growing environmental concerns have encouraged consumers, especially frugal individuals, to embrace sustainable consumption practices. By extending the lifespan of products and reducing frequent purchases, frugal consumers contribute to environmental sustainability (Dacyczyn 1998; Evans 2011; Lin and Chang 2012). Research has shown a positive association between frugality and sustainable consumption practices, particularly in finding innovative ways to prolong product life (Evers et al. 2018). Frugal individuals also exhibit a higher propensity to reuse and repair products (Albinsson et al. 2010) and an active search for alternative ways to extend the lifetime of their possessions (Evers et al. 2018).

Secondly, the global economic downturn experienced by many countries has compelled consumers to adopt increasingly frugal behaviors (Hampson and McGoldrick 2013). Frugality, as a behavioral pattern, can be triggered by external forces, such as the already mentioned economic downturns or personal setbacks. Additionally, individual differences and subjective motivations play a role in driving individuals towards frugal behaviors (Lastovicka et al. 1999; Bove et al. 2009; Kadlec and Yahalom 2011). In this context, Goldsmith et al. (2014) distinguished extrinsic and intrinsic drivers of frugality. For some people, extrinsic drivers predominate and then the characteristic patterns of frugal behavior, such as, for instance, cutting back on consumption or buying cheap goods, are observed to be repeated. For other people, on the other hand, intrinsic factors may surpass. In such cases, frugal behavior is driven by the individual’s beliefs, preferences, and interests rather than being forced by external circumstances. Following this intrinsic line, some authors considered frugality as a key driver influencing the way consumers behave (e.g., Pepper et al. 2009; or Roccas et al. 2002). Reinecke and Goldsmith (2016) even attributed to it a leading role in shaping consumer behavior. In this regard, Muiños et al. (2015) wrote about voluntary, deliberate, and proactive choices.

Thirdly, frugality represents a form of anti-consumption, voluntarily adopted by individuals seeking to reduce overall consumption levels (Albinsson et al. 2010; Khamis 2019; Kropfeld et al. 2018). For frugal consumers, anti-consumption becomes integral to their self-image, reflecting their ability to avoid frivolous expenses and engage in smart and efficient consumption practices. The rising interest in frugality is rooted in its alignment with sustainable values, its association with economic challenges, and its representation of a deliberate rejection of excessive consumption (Rose et al. 2010). In this perspective, frugal individuals make fewer purchases and claim economic rationality when making purchases (Michaelis et al. 2020), or even exhibit a dislike of purchases (Albinsson et al. 2010). In contrast to prevailing consumer culture, frugal individuals demonstrate ingenuity and adaptability in their consumption practices.

Increased attention to frugality and customer motivations is manifested not only by a number of scientific articles in peer-reviewed journals but also by attempts of many researchers to propose the relevant research tools for measuring the extent of frugality and its key determinants. In the center of these attempts, there is the Frugality scale (FS) developed by Lastovicka et al. (1999) that has become widely used (see, e.g., Todd and Lawson 2003; Pires et al. 2019; Santor et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2023), and it also has some adaptations (among others see e.g., Muiños et al. 2015). Although the original FS was introduced as a one-dimensional construct, some researchers ended up with a bifactor solution distinguishing financial management from resource management (Pires et al. 2019).

Reflecting the discourse on the dimensionality of the FS, the aim of this study was to assess the FS in Czechia and determine the number of factors. At the same time, the intention was to evaluate the reliability of the scale and demonstrate its construct validity. The hypotheses that were tested were as follows:

- (a)

- Based on the Czech data, FS has a unidimensional structure.

- (b)

- All eight items of the scale are correlated, and the scale has high internal consistency.

- (c)

- Psychometric properties of FS show a good fit of the theoretical model with data.

Frugality has received little attention in Czechia. Therefore, this study sheds light on this important driver of consumer behavior in this part of Europe, making it a novel contribution. The study represents the first validation of the FS within the Czech society, providing new evidence about this construct. The validation of FS allows for further investigations into frugality, enhancing understanding of specific aspects of consumer attitudes and behavior.

The analytical effort primarily focuses on examining the reliability and validity of the scale. FS was evaluated in terms of internal consistency and uni-dimensionality, along with its construct validity. Its applicability within the Czech society was thoroughly assessed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The research was designed in such a way that its results would provide insights into the attitudes and declared behavior of the Czech population. In this respect, the emphasis was placed on including both adolescents aged 15–17 and respondents whose age was 65–74 years at the time of the data collection. Data on the theoretical population were drawn from the census when the list of all houses and dwellings was used to design the sample (in the absence of data from the population register, such a list is a suitable alternative sampling frame). From this list, a selection was made in such a way that the selected units reflected the regional differences and distribution in terms of size of place of residence. Each interviewer was given 5–15 addresses at which an attempt was made to identify specific respondents using a Kisch table (Kish 1949).

The data collection took place in March 2023, when interviewers contacted individual households. In total, 2032 individuals were asked to participate in the survey. Due to the fact that some of those contacted refused to participate in the research, 1153 face-to-face interviews were conducted. Thus, the response rate was 53.2%. Informed consent was obtained from respondents before each interview. In the case of adolescent respondents, at least one of the parents was also invited to obtain informed consent.

All records were anonymized, and it was ensured that no specific person could be identified, either directly or indirectly. The completed questionnaires were subjected to a multi-stage check, during which 36 cases were excluded from further processing due to incompleteness of descriptive data or inconsistency of control variables. Therefore, the final sample contained 1117 valid cases. A total of 35% of the interviews conducted were screened using check-backs. Summary information on the data distribution is presented in Table 1, which also shows the similarity of the sample to selected parameters of the theoretical population, including the confidence intervals (95% CI). In addition to the FS itself, the research instrument contained other variables reflecting the relevant attitudes of the respondents and describing their behavior. It also contained a number of socio-demographic and socio-economic variables.

Table 1.

Selected socio-demographic characteristics.

Before incorporating the FS into the research instrument, the scale was translated into Czech and pilot tested. The process of translating the scale followed the recommended procedure described by Sousa and Rojjanasrirat (2011) and Yu et al. (2004). The initial translation of the scale was carried out by two independent translators who translated the individual items of the scale. The parallel translations produced were then compared with each other, with identified differences discussed with both translators. On the basis of their consensus, a consolidated translation of the scale in Czech was prepared. This was then back-translated by a third translator into English in order to check the consistency and equivalence of the Czech translation with the English original.

The next stage of scale editing focused on identifying potential errors and sources of bias. In this respect, the translation of the scale was examined for possible overlap in meaning between the stimuli and for inadequate use of vague and ambiguous words, jargon, etc. However, no significant errors were identified in these respects. The next steps of scale translation consisted of pilot testing the scale on a sample of 17 respondents who were recruited from the target population. These individuals were subjected to a pilot survey to identify any wording inconsistencies in the form of ambiguous wording. At this stage, the cognitive interview technique was applied, specifically, think-alouds were conducted (Willis 2005). The outcome of this stage was a finalized form of the FS, which was incorporated into the research instrument and used for the actual interviewing.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Frugality Scale (FS)

The Frugality Scale (FS), developed by Lastovicka et al. (1999), serves as a tool to measure respondents’ attitudes, feelings, and perceptions related to frugality. Consisting of eight items, the scale employs a six-point Likert-type response format ranging from 6 = definitely agree to 1 = definitely disagree. The total score on the scale ranges from 8 to 48, with higher scores indicating a higher level of frugality. The reliability and validity of the FS have been independently explored in various studies conducted by, e.g., Santor et al. (2020), Pepper et al. (2009), and Shoham and Brenčič (2004).

2.2.2. Direct Stimuli

Considering that frugality involves conscious reflection and efforts to manage and preserve possessions, the study also examined specific behavioral indicators related to individuals’ attempts. Through direct questions, respondents indicated the frequency of these behaviors using a five-point ordinal scale, where 5 = often, 4 = sometimes, 3 = seldom, 2 = exceptionally, and 1 = never. Table 2 provides an overview of key variables focusing on food waste, the reuse or repeated use of carrying bags, as well as the utilization of packages designed to minimize waste production (such as reusable or resealable packages). The underlying assumption here was that respondents who would score higher on the FS would be more likely to exhibit the observed patterns of behavior. That is, for example, they should have carried their own bag to the store to a greater extent, or they should have reported less food waste compared to other respondents.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the Direct Stimuli.

2.3. Data Analysis

In order to provide as detailed information as possible about the performance of the FS, a series of relevant tests and analyses were carried out. Firstly, a descriptive analysis of each variable was carried out. In addition to frequency analysis, means and standard deviations were calculated for the individual stimuli comprising the tested scale. Moreover, analyses aimed at describing the distribution of the data were performed, with skewness and kurtosis analyses. In assessing internal consistency, item-total correlations were calculated, and Cronbach’s alpha was used as well. It is worth mentioning that average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and floor and ceiling effects were assessed (Field 2017).

To validate the scale and verify the fit of the predicted model to the empirical data, both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted. Exploratory factor analysis aimed to identify the total number of factors using the principal components method, whereas confirmatory factor analysis verified the fit of the proposed model with respect to the nature of the data obtained using the maximum likelihood estimation method. In order to meet both of these objectives, the dataset was divided into two equivalent subsets using a random number generator, where the first subset (n = 552) was based on exploratory factor analysis, while the confirmatory task was performed on the second subset (n = 553). This recommended procedure (Furr 2011) has already been used to examine the psychometric properties of another scale (Remr 2023). The varimax rotation method with Kaiser Normalization was used to conduct the exploratory factor analysis. The CFA included validation of the usual set of absolute and incremental indices. In addition, the model tested was optimized to account for potential errors associated with unobserved variables whose variance could not be explained within the model.

Missing values were handled by the listwise method, whereas other valid cases available for the sub-analysis were used in the analysis of the other variables. For this reason, the bases for each finding differ. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 27 software, with the exception of the confirmatory factor analysis, which was performed in AMOS 24 software.

3. Results

3.1. Univariate Statistics

As can be seen from Table 3, the FS achieved a total score of 35.87 in the research conducted, with a standard deviation of 6.613. The table also shows the mean scores for each item along with its standard deviation. For comparison, it is worth noting that Lastovicka et al. (1999) found a means value of 40.43.

Table 3.

Selected Statistics of the Frugality Scale (FS) and Its Items.

None of the items show a different pattern of ratings from the others, with values of the means ranging from 4.14 to 4.74 and values of the standard deviations ranging from 1.027 to 1.168. In terms of the values distribution, the floor and ceiling effects are useful. These values are 0.0% and 2.2%, respectively, which can be considered adequate. Similarly, the values of skewness and kurtosis are within the acceptable range, according to Cain et al. (2017).

3.2. Uni-Dimensionality and Internal Consistency

The assumed uni-dimensionality of the scale is evidenced by the results of the exploratory factor analysis. Indeed, using the principal components method, only one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1 was extracted. In this regard, it should be noted that the sampling adequacy rate was 0.905, which confirms the suitability of the input data for the exploratory factor analysis. In this regard, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significant result with χ2 = 1993.241 (df = 28, p < 0.001), and the coefficient of determination reached a value of 55.9%, indicating that the identified factor explains more than half of the variance. According to Pett et al. (2003), such value is adequately high to inform on the meaningfulness of the factor analysis performed.

Table 4 reports the factor loadings and communalities of all eight items in the scale. The results show the highest factor scores for the item “I believe in being careful in how I spend my money”, while the lowest value was for the item “There are things I resist buying today so I can save for tomorrow”. According to Hogarty et al. (2005), a factor score greater than 0.4 can be considered a significant contribution, which is the threshold that all items in the scale tested reached.

Table 4.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (FS).

The assumed uni-dimensionality was evidenced by the high value of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which in this study was 0.886. In relation to the overall consistency of the scale, the contributions of the individual items were also analyzed. The eight-item solution tested was found to be optimal in terms of internal consistency. In fact, none of the items would worsen the overall consistency of the scale. Moreover, the possible removal of any of the items would not lead to an increase in the internal consistency of the scale (Raykov 1997). The correlations between the items ranged from 0.640 to 0.729, i.e., all values exceeded the 0.4 threshold recommended by Tavakol and Dennick (2011). Therefore, the results support the claim that the individual items of the scale indeed reflect the intended construct and can be used as a whole to measure frugality.

3.3. Psychometric Performance of the Frugality Scale

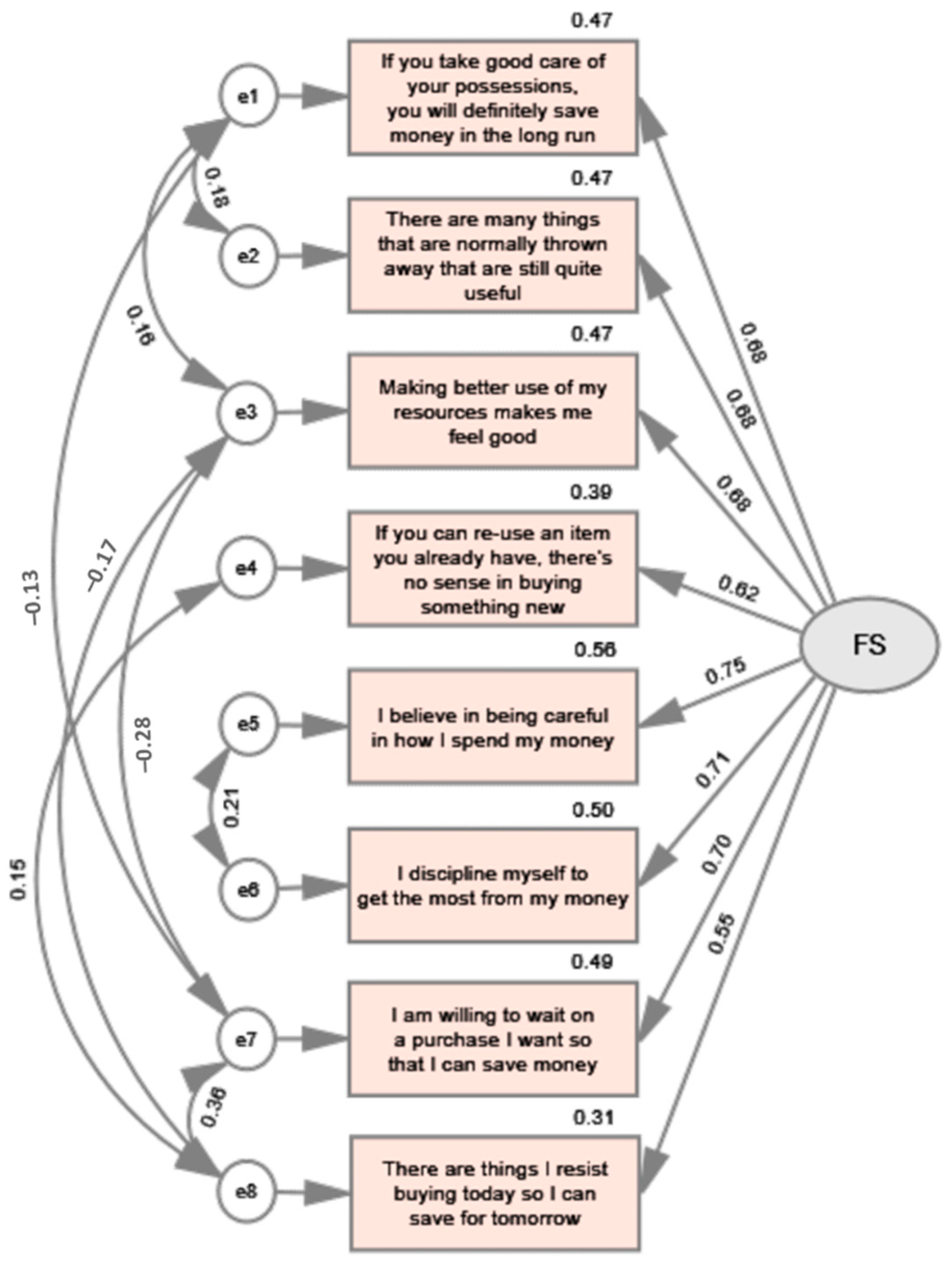

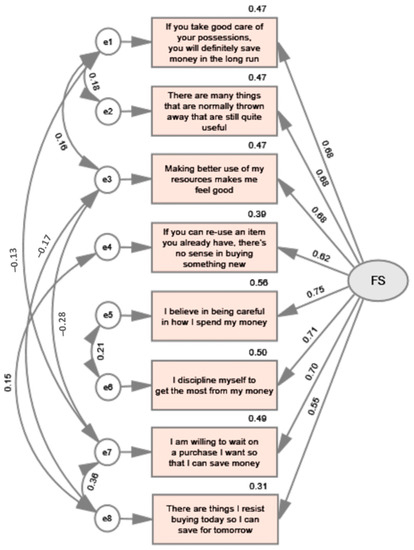

The construct validity and psychometric properties of the scale were tested on a separate subset (n = 553) independently of the results of the exploratory factor analysis. To this end, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation. The model tested can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (FS) of the Improved Model.

As the tested model achieved a chi-square value of 24.078 with df = 12 (p = 0.020), it was necessary to compute other indices to assess the fit of the model to the data (Pituch and Stevens 2016). In this regard, a set of absolute and incremental indices were used, where in addition to the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and the normalized fit index (NFI) were also assessed.

From the data summarized in Table 5, it can be seen that the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) reached a value of 0.043, and the value of the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was 0.0186, which are values that are below the recommended thresholds and indicate that the theoretical model reflects well the data obtained (Comrey and Lee 2013). The goodness of fit of the proposed model is further characterized by the goodness of fit index (GFI) quantifying the proportion of variance in the observed covariance matrix (Hu and Bentler 1998), which reached a value of 0.989, and the comparative fit index (CFI) comparing the fit of the hypothetical model with the baseline model, which reached a value of 0.993. The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and the Normalized Fit Index (NFI) also indicate a very good fit of the theoretical model to the data (Byrne 2001). Based on the values obtained, it can be concluded that the tested model adequately represents the data. In other words, with respect to the values of the key indices, it can be concluded that the FS performs very well.

Table 5.

Absolute and Incremental Indices (FS).

3.4. Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was analyzed through the average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). In this regard, the FS achieved an AVE value of 0.56, i.e., the latent variable explains 56% of the variance of the indicators. Since this value exceeds the recommended threshold, which, according to Bardhoshi and Erford (2017), is 0.4, it could be concluded that the latent variable adequately represents the construct being tested. Moreover, the value of composite reliability (CR) indicates a high correlation between the items of the latent variable when it reaches a value of 0.91.

3.5. Construct Validity

Furthermore, a high correlation between the scale items may indicate that they measure the same construct (Furr 2011), and therefore, the correlation matrix is used to demonstrate construct validity (see, among others, Nunnally and Bernstein 1994; Brown 2015; Schreiber et al. 2006). In this regard, the correlation matrix presented in Table 6 shows that all eight stimuli consistently measure the same construct, as all items are significantly correlated with each other.

Table 6.

Correlation matrix (FS).

Construct validity can be further evidenced by the relationship of the scale scores with known predictors. In this regard, the study included questions on general interest in waste and specifically an attempt to avoid food waste, using own bags at the stores, overall concerns with the economy (i.e., inflation, price level), and perceived affordability of consumer goods. Table 7 shows how the FS scale scores varied across respondent groups.

Table 7.

Frugality Scale (FS) by the relevant attitudes and reported behaviors.

The obtained results show statistically significant associations with all hypothesized variables, with the exception of perceived affordability. Significant associations with the selected indicators fitted with the expected frugal attitudes. In fact, the perceived affordability that did not show statistically significant associations also corresponds to the construct of frugality because it is considered rather as a state of mind and the deliberate intention to spare resources and avoid overconsumption (see, e.g., Albinsson et al. 2010), instead of the consequence of limited financial resources.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to test the psychometric properties of the FS in the context of Czech society. To achieve this goal, various testing methods were combined, including the assessment of internal consistency, principal components analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis. Based on the formulated hypotheses, the data analysis supported the conclusion that FS has a uni-dimensional structure in the Czech context. The scale demonstrated internal consistency with favorable item-total correlations and a high Cronbach’s alpha value. Moreover, exploratory factor analysis revealed a single factor underlying all eight items indicating a high level of internal consistency. Besides, confirmatory factor analysis supported the goodness of fit of the proposed model to the empirical data, as indicated by the absolute and incremental fit indices. Additionally, the results showed significant associations between FS and relevant attitudinal and behavioral patterns. Notably, the scale exhibited a strong correlation with pro-environmental behavior. It was also associated with resource efficiency and price sensitivity, as reported in other studies (Gil-Giménez et al. 2021; Pinto et al. 2011; De Young 1996; Pan et al. 2019; Shoham and Brenčič 2004). Moreover, the study revealed interesting demographic associations. Age and gender were statistically significant factors linked to FS scores, with older respondents displaying higher frugality values than younger ones and females scoring higher than males. These findings add further depth to the understanding of frugality and its relevance in Czech society.

Moreover, the results revealed that respondents with a consistent and value-based interest in good waste management scored significantly higher on the FS compared to others. This finding aligns with numerous other studies, demonstrating a positive correlation between frugality and environmental behavior (see Lin and Chang 2012; Evans 2011; or Evers et al. 2018). Additionally, concerning environmental attitudes, it is evident that respondents who brought their own shopping bags to the store achieved a significantly higher frugality score. Specifically, those who often carried their own shopping bags obtained an FS value of 37.67, while respondents who reported never bringing their bags scored 32.12. Similar results were observed when evaluating the degree of importance respondents attached to packaging design that prevents wastage. Here, individuals who consider this characteristic important scored 37.06 on the FS, while those who attached no importance to it scored 33.46. The results are consistent with findings from other studies examining the relationship between environmental attitudes and frugality. Notably, they indicate that frugality at the individual level is not solely a matter of value orientation but also translates into specific behavioral patterns performed daily.

One particular area that lies at the crossroads between frugality and environmental concerns is the issue of food waste. The study highlighted a significant discrepancy between respondents who confirmed the importance of not wasting food and others. Those who expressed efforts to reduce food waste scored significantly higher on the FS (37.34) compared to respondents with an opposite attitude towards food waste, who scored 32.02. This finding further substantiates the core principles of frugality as presented by Lastovicka et al. (1999).

In the context of frugality, several sources delve into money perception, financial management, and handling of finances. This research also examined this aspect. Specifically, respondents who showed concern about these financial matters demonstrated higher levels of frugality, scoring 36.84 on the FS, compared to other respondents who scored 30.86.

Finally, a noteworthy observation was that FS scores did not significantly differ based on the perceived affordability of consumer goods. FS values remained consistent in this regard, suggesting a predominant influence of intrinsic drivers over extrinsic determinants. From these results, it becomes evident that frugality was a product of an individual’s own decisions, willpower, and motivation, rather than being solely influenced by external circumstances, such as scarce resources.

The implications of this study are threefold:

- (a)

- Academic: The validated research tool in the form of the frugality scale will facilitate in-depth and specific data analysis to identify individual patterns of consumer behavior. Examining this construct using a purposefully designed robust scale allows for a better understanding of the nature of frugality in the individuals being surveyed and provides greater insight into the mindset and attitudes in this area. The applicability of the insights gained is significantly broader since, in addition to consumer behavior itself, frugality also has implications for financial literacy and sustainable behavior (Suárez et al. 2020). Additionally, it opens avenues for further exploration of the relationship between frugality and other related constructs such as voluntary simplicity, value consciousness, money attitudes, and thriftiness. These associations can contribute to enhancing models of purchasing behavior and may lead to valuable meta-analyses.

- (b)

- Practical: Better insight into respondents’ thinking about resource management practices improves the position of policymakers in designing specific measures and policies that aim to promote resource conservation or reduce waste. Careful analysis based on a robust methodology allows for better differentiation between social groups so that specific interventions can be better targeted to the desired populations.

- (c)

- Managerial: The study’s significance extends to management, particularly in profiling the target group and describing the purchasing behavior of current customers. For instance, considering customer frugality may become essential at various product lifecycle stages, especially the estimation of the late-majority customers and the laggard ones is important since these two groups are likely to attract frugal individuals. Understanding the distribution of frugal customers can aid in making better product planning, tailoring innovation, and using better strategies to suit the needs and preferences of relevant customer segments. The results of this study can, therefore, assist in developing customer profiling methodologies and refining strategies, reflecting the frugality of their customers.

However, the research conducted has some limitations. Since it was designed as a cross-sectional study, the direction of the identified associations cannot be reliably determined. Thus, it is not possible to analyze the correlation between frugality and pro-environmental behavior in much detail (Churchill 1979; DeVellis 2016). It, therefore, remains unclear whether increased frugality leads to sustainable behavior or, conversely, whether sustainable behavior (primarily driven by greater environmental responsibility) leads to increased frugality. Similarly, it is not possible to use the available data to credibly prove the reasons why older respondents show a higher propensity to frugality. There may be several scenarios in this regard (see, inter alia, Todd and Lawson 2003; Lastovicka et al. 1999; or Bove et al. 2009), but the existing data do not suggest any. Thus, the results obtained only identify and describe particular associations, but other, specifically targeted research will be needed to explain them. Another limitation relates to the fact that the research conducted relies on self-reported data. These may be burdened with all sorts of response biases (see, e.g., Biemer and Lyberg 2003 for details). The last restriction concerns the general social context in Czechia. After many years of relatively stable economic development, the country faced double-digit inflation and a sharp increase in energy prices in 2022. This may have affected the way many individuals approached resource management and the way they planned their household budgets and thought about their consumption behavior and purchasing priorities. For this reason, it would be desirable to replicate the research on the same population at a later date, when the economic situation has stabilized again.

5. Conclusions

The research conducted is among the multitude of studies that emphasize frugality as one of the important drivers of consumer behavior. Based on the data collected, the tested research instrument in the form of the FS has been shown to be suitable for further use and capable of providing useful insights about the target group. In this regard, it should be pointed out that the psychometric properties of the scale were very good, as well as its internal consistency, reliability, and validity. On the basis of the results obtained, the FS can be used either with the aim of researching customer attitudes and mapping the key drivers of purchasing behavior or as an explanatory (or independent) variable in complex attitudinal or behavioral models.

The results obtained not only provide information about the Czech population but also provide other researchers with new ideas for further investigation, outline directions for further research and ultimately contribute to the validation of the FS as such.

Funding

This submission was funded by Operation Program Research, Development and Education, European Structural and Investment Funds, and by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, grant number/registration number CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/18_054/0014660 as a part of the project “Setting the conditions and the environment for international and cross-sector cooperation”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/, accessed on 8 August 2023) and follows the Ethical code of AAPOR (https://www.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/AAPOR-Code-of-Ethics.aspx, accessed on 8 August 2023). The research design as well as the research instrument (the questionnaire) were approved in INESAN by the Research Ethics Board (IREBA/2023/312). The institute holds HRS4R HR Excellence in Research award (https://inesan.eu/en/hrs4r-2/, accessed on 8 August 2023) which acknowledge the highest standard of ethics carried-out by researchers at this institute (https://www.euraxess.cz/jobs/hrs4r, accessed on 21 March 2023). All links were accessed on 8 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. This study involved data collected from anonymous respondents. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before their participation in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would thanks to all interviewers engaged in this study and to all members of the supportive research team.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Albinsson, Pia A., Marco Wolf, and Dennis A. Kopf. 2010. Anti-consumption in East Germany: Consumer resistance to hyper consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 9: 412–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhoshi, Gerta, and Bradley T. Erford. 2017. Processes and procedures for estimating score reliability and precision. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 50: 256–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemer, Paul P., and Lars E. Lyberg. 2003. Introduction to Survey Quality. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bove, Liliana L., Anish Nagpal, and Adlai David S. Dorsett. 2009. Exploring the determinants of the frugal shopper. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 16: 291–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2001. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. In Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, Meghan K., Zhiyong Zhang, and Ke-Hai Yuan. 2017. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behavior Research Methods 49: 1716–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Gilbert A. 1979. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 16: 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, Andrew L., and Howard B. Lee. 2013. A First Course in Factor Analysis. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dacyczyn, Amy. 1998. The Complete Tightwad Gazette: Promoting Thrift as a Viable Alternative Lifestyle. New York: Villard Books. [Google Scholar]

- De Young, Raymond. 1996. Some psychological aspects of reduced consumption behavior: The role of intrinsic satisfaction and competence motivation. Environment and Behavior 28: 358–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, Robert F. 2016. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, David. 2011. Thrifty, green or frugal: Reections on sustainable consumption in a changing economic climate. Geoforum 42: 550–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, Uwana, Richard L. Gruner, Joanne Sneddon, and Julie A. Lee. 2018. Exploring materialism and frugality in determining product end-use consumption behaviors. Psychology & Marketing 35: 948–56. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2017. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 5th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Furr, Mike. 2011. Scale Construction and Psychometrics for Social and Personality Psychology. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Giménez, Domingo, Gladys Rolo-González, Ernesto Suárez, and Gabriel Muiños. 2021. The Influence of Environmental Self-Identity on the Relationship between Consumer Identities and Frugal Behavior. Sustainability 13: 9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Ronald E., Leisa Reinecke Flynn, and Ronald A. Clark. 2014. The etiology of the frugal consumer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, Daniel P., and Peter J. McGoldrick. 2013. A typology of adaptive shopping patterns in recession. Journal of Business Research 66: 831–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, Kelly, Rebecca Walker Reczek, Robin A. Coulter, and William O. Bearden. 2012. Keeping it all without being buried alive: Understanding product retention tendency. Journal of Consumer Psychology 22: 224–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarty, Kristine Y., Constance V. Hines, Jeffrey D. Kromrey, John M. Ferron, and Karen R. Mumford. 2005. The Quality of Factor Solutions in Exploratory Factor Analysis: The Influence of Sample Size, Communality, and Overdetermination. Educational and Psychological Measurement 65: 202–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under-parameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods 3: 424–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, Dan, and Tali Yahalom. 2011. How the economy changed you. Money 40: 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, Susie. 2019. The aestheticization of restraint: The popular appeal of de-cluttering after the global financial crisis. Journal of Consumer Culture 19: 513–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish, Leslie. 1949. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. Journal of the American Statistical Association 44: 380–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropfeld, Maren Ingrid, Marcelo Vinhal Nepomuceno, and Danilo C. Dantas. 2018. The ecological impact of anti-consumption lifestyles and environmental concern. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 37: 245–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lastovicka, John L., Lance A. Bettencourt, Renee S. Hughner, and Ronald J. Kuntze. 1999. Lifestyle of the tight and frugal: Theory and measurement. Journal of Consumer Research 26: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Ying-Ching, and Chiu-chi Angela Chang. 2012. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. Journal of Marketing 76: 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, Timothy L., Jon C. Carr, David J. Scheaf, and Jeffrey M. Pollack. 2020. The frugal entrepreneur: A self-regulatory perspective of resourceful entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing 35: 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiños, Gabriel, Ernesto Suárez, Stephany Hess, and Bernardo Hernández. 2015. Frugality and psychological wellbeing. The role of voluntary restriction and the resourceful use of resources. Psyecology 6: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jum C., and Ira H. Bernstein. 1994. Validity. Psychometric Theory 3: 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Li Sunny, Tod Pezzuti, Wei Lu, and Cornelia Connie Pechmann. 2019. Hyperopia and Frugality: Different Motivational Drivers and yet Similar Effects on Consumer Spending. Journal of Business Research 95: 347–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, Miriam, Tim Jackson, and David Uzzell. 2009. An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33: 126–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett, Marjorie A., Nancy R. Lackey, and John J. Sullivan. 2003. Making Sense of Factor Analysis. London: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Diego Costa, Walter Meucci Nique, Edar da Silva Añaña, and Márcia Maurer Herter. 2011. Green consumer values: How do personal values influence environmentally responsible water consumption? International Journal of Consumer Studies 35: 122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, Pedro P., Ana Carolina Monnerat Fioravanti Bastos, Érica de Lana Meirelles, Júlia Mulinari Peixoto, Natacha de Barros Candido, and Leonardo de Barros Mose. 2019. Factorial Structure of the Frugality Scale: Exploratory Evidence. Psico-USF 24: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituch, Keenan A., and James P. Stevens. 2016. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS, 6th ed. New York: Routledge Taylor & Frances Group. [Google Scholar]

- Raykov, Tenko. 1997. Scale reliability, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, and violations of essential tau-equivalence with fixed congeneric components. Multivariate Behavioral Research 32: 329–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, Flynn Leisa, and Ronald Earl Goldsmith. 2016. Filling some gaps in market mavenism research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 16: 121–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remr, Jiri. 2023. Validation of the Health Consciousness Scale among the Czech Population. Healthcare 11: 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, Sonia, Lilach Sagiv, Shalom H. Schwartz, and Ariel Knafo. 2002. The big five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28: 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Maria, João F. Proença, and Rita Macedo. 2023. Determinants of the Purchase of Secondhand Products: An Approach by the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability 15: 10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Paul, Shannon Toney Smith, and Daniel J. Segrist. 2010. Too cheap to chug: Frugality as a buyer against college-student drinking. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 9: 228–38. [Google Scholar]

- Santor, Darcy A., Fethi Ihssane, and Sara-Emilie McIntee. 2020. Restricting Our Consumption of Material Goods: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 12: 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, James B., Amaury Nora, Frances K. Stage, Elizabeth A. Barlow, and Jamie King. 2006. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. Journal of Educational Research 99: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, Aviv, and Maja Makovec Brenčič. 2004. Value, price consciousness, and consumption frugality: An empirical study. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 17: 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Valmi D., and Wilaiporn Rojjanasrirat. 2011. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 17: 268–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, Peter N. 2001. Consumerism in World History: The Global Transformation of Desire. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, Ernesto, Bernardo Hernández, Domingo Gil-Giménez, and Víctor Corral-Verdugo. 2020. Determinants of Frugal Behavior: The Influences of Consciousness for Sustainable Consumption, Materialism, and the Consideration of Future Consequences. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 3219. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, Mohsen, and Reg Dennick. 2011. Making sense of Cronbach´s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education 2: 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, Sarah, and Rob Lawson. 2003. Towards an understanding of frugal consumers. Australasian Marketing Journal 11: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, Richard. 2001. Consuming morality. Journal of Consumer Culture 1: 245–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Gordon B. 2005. Cognitive Interviewing in Practice: Think-Aloud, Verbal Probing, and Other Techniques. New York: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, Terrence H. 2010. A brief history of frugality discourses in the United States. Consumption Markets & Culture 13: 235–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Doris S., Diana T. Lee, and Jean Woo. 2004. Issues and challenges of instrument translation. Western Journal of Nursing Research 26: 307–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavestoski, Stephen. 2002. The social–psychological bases of anticonsumption attitudes. Psychology & Marketing 19: 149–65. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).