Abstract

The research aims to identify individual value-creation indicators, which are provided to suppliers, and their significance in building and maintaining sustainable, long-lasting mutual relationships between enterprises and their suppliers. The enterprises (in the position of suppliers) assigned the importance of the individual value-creation indicators which are provided to them and expressed the level of satisfaction with the relationships with their buyers. The research was carried out through structured questionnaires and collected answers from 112 managers of enterprises from Slovakia. Research results include the list of 21 individual value-creation indicators (defined in the questionnaire) and show which value-creation indicators are provided to the enterprises (suppliers) the most, which of these indicators are essential for the suppliers, and if the suppliers are provided with the values, they consider significant. The analysis of individual value creation indicators was done separately using Chi-squared and Cramer’s V tests and Rank–Biserial Correlation. The logistic regression was used to analyze all factors and their influence on the relationship between suppliers and the enterprise. Enterprises (suppliers) are generally satisfied with their relationship with buyers. However, almost 19% of suppliers consider their relationship neutral or unsatisfying. This result points out that there is room for improvement, which can be done by providing significant value-creation indicators to suppliers.

1. Introduction

The relationship between the stakeholders and the enterprise can be defined based on two continuous flows. Each of these stakeholders contributes something to the enterprise and, on the other hand, receives something from it (Post et al. 2002).

In managing the relationship between the enterprise and its suppliers, the enterprise must select key suppliers to whom it will devote the effort, financial resources, and other resources such as time to ensure their loyalty and good long-term relationships. Subsequently, the enterprise needs to monitor the results and development of these relationships over time. The enterprise’s interaction with other organizations or stakeholders is called inter-organizational relationship (IOR). These are of great importance for the enterprise’s performance (Mandt 2018). Managing the supplier relationship is important for identifying the value-creation indicators that help the enterprise select and provide value. In this way, they ensure the provision of just the important value to suppliers, resulting in good and sustainable relationships. These relationships lead to loyalty, trust, mutual tolerance, and long-term cooperation. Decisions require flexibility to respond to market demands, so managers need a flexible information system with a high-quality selection of information (Chodasova and Tekulova 2016). These relationships should lead to efficient business. For all stakeholders involved, it means achieving maximum results with minimum investments (Prusa et al. 2020).

The research aims to show that the value creation process through providing value creation indicators impacts the relationships between enterprises and their suppliers.

One of the essential factors in the value-creation process is the mutual relationship between the enterprise and its stakeholders. The research provides value-creation indicators through which enterprises build and maintain supplier relationships. The main parts of the research are:

- a connection between the provided indicators and the built relationships;

- the significance of the indicators perceived by suppliers; and

- the list of value creation indicators that can be provided to suppliers.

In the value creation process is important to know the suppliers’ needs, frustrations, and opinions. Therefore, when providing value-creation indicators to suppliers, it is critical to know which indicators are significant for them. Then the enterprise can avoid providing value-creation indicators which are not crucial for suppliers and can focus on these which are meaningful to them. Therefore, a list of 21 value-creation indicators was created and provided to the suppliers to specify their significance. Afterward, the provision of the indicators was linked and compared with the satisfaction rate of the mutual relationship between the enterprises and their suppliers. This way, enterprises can determine which value-creation indicators lead to good long-term relationships. When an enterprise knows the significance of the indicators, it can focus its resources, such as time and finances, on meaningful ones.

The research focuses on the following problems:

- The ambiguity and inadequacy of information on the reception of suppliers’ value creation indicators. Their perception is from the perspective of both sides: the enterprise and the suppliers;

- The individual indicators of value creation provided to suppliers are not identified.

- The importance of these indicators, attributed to them by suppliers, is not determined. Therefore, it is important to identify indicators and their relation to building a relationship between the suppliers and the enterprise;

- The degree of acceptance of individual indicators of value creation and its comparison with the actual importance attached to the given indicator is unclear.

The relationship between enterprises and their suppliers is the main subject dealt with by Supplier Relationship Management (SRM). The company State of Flux from the United Kingdom publishes Global SRM Research Report every year, focusing on who is responsible for SRM questions, what are the pillars of SRM, what is the value, what is the goal of building sustainable mutual relationships with suppliers, and many others (State of Flux 2022). However, these studies usually deal with the subject based on the enterprises’ (buyers’) points of view. What are their goals, what do they want to achieve, and why is it beneficial? There is room for consideration of suppliers’ points of view. Is it beneficial what the enterprises are doing? Are the suppliers provided with values significant to them? Do they perceive the values provided by enterprises? For enterprises (buyers) is important to know if the value they are providing to suppliers is perceived by them and if such provision has any influence on the mutual relationship they are trying to build. Based on the given facts, the following research questions were formulated:

- Which value creation indicators are significant in building a supplier’s relationship with its buyers?

- How do enterprises (suppliers) evaluate their relationship with their buyers?

- Which value creation indicators are provided to the suppliers the most?

- Which value creation indicators are the most important for the suppliers?

- Are suppliers provided with precisely the values they consider most important?

2. Literature Review

The literature review consists of three main sections: Value and value creation, Indicators in the value creation process, and Buyers-suppliers relationship. The main reason is to provide an individual explanation for a better and deeper understanding of their connection. These three subjects are linked within the further sections.

2.1. Value and Value Creation

As the term value has many meanings, it is crucial to define it initially. The primary theoretical basis for the research is the international standards EN 1325:2014 Value Management—Glossary—Terms and Definitions (BSI 2014) and EN 12973:2020 Value Management (BSI 2020). The given international standards define value as the degree to which a project, product, or enterprise satisfies the needs of stakeholders concerning the resources consumed. According to Davies and Davies (2011), value is the difference between achieved results and resources. Turner (1990) sees value as a marginal utility. Leung and Liu (2003) point out that value is a subjective view of things, and Aliakbarlou et al. (2017) add that value has a dynamic nature that constantly changes over time. According to Cha and O’Connor (2005), value has no single and proper definition, as it has an essentially abstract concept.

Value creation focuses on owners and final customers. However, creating long-term value for the owners themselves also requires other stakeholders’ satisfaction. The enterprise can only create this long-term value if it recognizes the needs of other stakeholders (Goedhart et al. 2020). Value creation is linked to several stakeholders (customers, business partners, intermediaries, suppliers, and other partners). The reason is that all these stakeholders have a common need, which is not only the creation of value but also its acquisition and appropriation (Brandenburger and Stuart 1996). Cooperation with stakeholders is an important factor in an enterprise’s ability to manage this cooperation, which means balancing a value creation strategy and a value appropriation strategy (Gnyawali and Charleton 2018). The supplier is portrayed as the element in the value creation process, which creates added value for the final consumer. Increasing the enterprise’s overall productivity is one of the factors enabling the creation of added value and achieving long-term growth. Through productivity growth, enterprises are more competitive in the local market and also the national and international markets (Chodasova et al. 2015). Choosing the right supplier is an important decision for an enterprise. This decision also significantly impacts the enterprise’s management (stocks, quality, costs, profit, sales). Therefore, the enterprise should constantly maintain the relationship with such a supplier and ensure long-term cooperation and loyalty.

The basic elements of gaining a competitive advantage within B2B are, on the one hand, the creation of value and, on the other hand, its acceptance (Eggert et al. 2019). However, most publications focus on value creation as the ratio of an enterprise’s benefit to the price it has to pay (Geiger et al. 2015; Gronroos and Helle 2010). However, enterprises have now begun to realize that if they provide value to other stakeholders (e.g., suppliers), they may not only focus on cash returns but will be rewarded by the loyalty of these stakeholders, strengthening competitiveness or long-term cooperation. Providing value becomes a benefit for both parties. Granovetter (1985) and Morgan and Hunt (1994) have already pointed out the importance of long-term mutual cooperation and building links between supplier and buyer.

The building of mutual relationships leads to the expected behavior, which reduces the imposition of the other party and thus leads to a reduction in transaction costs. The business strategy is being revised towards more sustainable production methods, business processes, resource efficiency, waste disposal, partnership building, and communication efficiency (Hitka et al. 2019). Thus, achieving a particular goal becomes essential. The main difference in the perception of achieving a goal is whether the goal is based on expectations or experience. Subsequently, value creation is perceived when the agreement is entered into and reflects all the expected consequences of the transaction in terms of objectives for both the buyer and the supplier (Eggert et al. 2019). An important element in the value creation process is the resources that the enterprise and the stakeholders have at their disposal. The use of these resources needs to be reconsidered, especially when the goal is to create value (Huemer and Wang 2021).

The basis of the value creation process is a business model the enterprise chooses and implements (Climent and Haftor 2020). Spieth et al. (2019) defined four basic factors of business models: responsible efficiency, the complementarity of impacts, common values, and integration innovations as part of the value creation process. These business models have become an important tool for managers to understand the logic of value creation and identification (Martins et al. 2015). One of the effects of creating business models is analyzing their effects and results (Abdelkafi and Tauscher 2016). Clarifying measurable results in project management for process improvement and process change is important. The advantages of their use are cost savings and performance improvement processes (Simanova et al. 2019). It is also important to find the modern approach as the traditional methods have many disadvantages. One of them is that they analyze the past, and predicting future development is almost impossible (Tokarcikova et al. 2014).

2.2. Indicators in the Value Creation Process

International Standard EN 12973: 2020—Value Management further states that an enterprise should apply value management principles in defining objectives and potential variables. The action plan and the indicators should be defined in terms of functionality and value. It also recommends that consideration should be given to the overall impact of all indicators to obtain information on progress towards the objectives set while providing information to the person responsible for implementing the decisions.

Economic data and indicators help businesses identify what will happen in the future, and enterprises can invest accordingly to reap profits later (Constable and Wright 2011). According to the UNAIDS study, the indicator provides information that something exists and is valid (Hales et al. 2010). This study further argues that a good indicator should be clearly defined and should focus on one issue where relevant information on the situation needs to be obtained, mainly information that provides the strategic overview required for effective planning and decision-making. KPMG Study (2016) characterizes indicators as measurable variables whose primary purpose is to provide information on specific aspects of the research process. Hart (1999), Wolf and Chomkhamsri (2012) set out the primary criteria for selecting indicators. These criteria include robustness, relevance, efficiency, clarity, ease of measurement, and practicality. Within the research focused on the enterprise’s relationship with its business partners, the connection between value creation and individual indicators is becoming increasingly apparent. In this case, it is first necessary to identify the needs of stakeholders and then identify indicators.

According to the international standard EN 12973: 2020—Value management is an indicator of a specific attribute, where each change affects the value of the assessed entity. When defining goals, the enterprise should follow the principles of value management. It also applies to the identification of potential variables. The definition of indicators should be both functional and value-based. All key indicators affecting the growth and performance of the enterprise can be divided into financial and non-financial (Tokarcikova et al. 2014). After defining the indicators, the enterprise should then focus on their perception. It should be necessary for the enterprise to focus on the recipient’s perception. The paper focuses on indicators of value creation for the supplier, on their perception by the given stakeholder, and on the influence of these indicators on the mutual relationship between the enterprise and suppliers. According to Demuth (2013), perception is receiving information that is subsequently processed, transformed, and modified.

2.3. Buyers-Suppliers Relationship

All market players try to get the best resources from the same supplier (Takeishi 2002). Supplier satisfaction is one of the primary determinants of the supplier’s buyer selection process (Pulles et al. 2016). That is why enterprises try to create value for the suppliers and thus ensure their satisfaction, loyalty, long-term cooperation, access to the necessary resources, better technologies, better quality, or other supplier benefits (Vos et al. 2021). Collaboration with suppliers is crucial for the enterprise to ensure its performance and competitiveness in the market (Yen and Hung 2017). It is necessary to be aware of the value and importance of individual people (stakeholders in the process) to ensure the competitiveness of the enterprise in the domestic as well as the global market (Kucharcikova and Miciak 2017). Cooperation between suppliers and buyers (B2B) is influenced by problems resulting from economic, social, and environmental factors (Jánošová 2021). One way to prevent these problems is to maintain fairness in the relationship between buyers and suppliers. It is a matter of observing business conditions and good interpersonal relations between the given business partners (Luo 2009). These factors are also indicators in the value creation process. Sufficient resources are needed to create value for stakeholders. All enterprises strive to meet the needs of given stakeholders (including business partners) through limited resources, which become their driving force to achieve sustainable development.

The basis of a good relationship between a supplier and its buyers is trust based on mutual information. Partners are willing to provide comprehensive information through mutual trust based on solid relationships (Carey et al. 2011). Providing information and obtaining opinions, suggestions, or feedback are other indicators of the value-creation process. It is trust based on long-term cooperation that prevents information leakage, where information can be misused by buyers for their own benefit (Zhou et al. 2014), or information can get into competition (Li and Zhang 2008), which is why suppliers are willing to share information only if they build a relationship and trust with the buyer. The value creation process helps the enterprise create relationships and trust with its business partners.

Calculating the economic return on any investment in motivation is very difficult because it is based on a complex quantification of measurable benefits for the enterprise (Hitka et al. 2017). One of the main goals of any organization is to achieve as much efficiency and profit as possible (Prusa et al. 2020). Strong corporate social responsibility can also enhance a company’s reputation and maximize its profit. Profit also depends on the competitiveness of the enterprise. Competitiveness is actually “competing with other enterprises in the given branch” (Tekulova et al. 2016).

This research aims to combine the findings of various studies on value creation and its perception into one study and evaluate their impact on suppliers’ satisfaction with the relationship with their buyers. As a result, research questions were proposed and are listed in the introduction. Subsequently, research was carried out on indicators of value creation and their impact on the supplier’s relationship with its buyers.

The topics concerning value creation processes are essential for enterprises to build and maintain stakeholder relationships. Realizing that the value creation process and building relationships are closely related is important. Most of the papers show the importance of these topics in general. However, there is not a highlighted connection between them. The research shows that the value creation process through providing value creation indicators might impact the relationships between enterprises and their suppliers. It is also imperative for enterprises to know which value-creation indicators are significant for their suppliers. Specific options and recommendations need to be provided in order for enterprises to be able to identify opportunities for value creation. Therefore, the list of 21 value-creation indicators for suppliers was created and presented to the suppliers to enable enterprises to identify which indicators are significant for suppliers and which are not.

3. Material and Methods

The research aims to show that the value creation process through providing value creation indicators impacts the relationships between enterprises and their suppliers.

For the purpose of this goal, the survey focused on Business to Business (B2B). The main reason is that the research deals with the relationships between the enterprises (buyers) and their suppliers. Therefore, choosing enterprises with suppliers and whose buyers are not just final customers but businesses to obtain relevant data was significant. For this purpose, we had to choose enterprises that fit the mentioned requirements.

Based on the studies focusing on Supplier relationship management (SRM), literature review, and information from practice, a list of 21 value-creation indicators was created. In our opinion, these indicators influence the mutual relationships between enterprises and their suppliers in the B2B sector.

The survey was carried out using an online structured questionnaire created in Google Forms that was sent to 3820 companies. These companies were selected based on the requirements concerning having suppliers and buyers (B2B). We approached 3820 companies, of which 3.87% participated in the survey. The questionnaire should have been filled out by managers of the enterprises. After cleaning the data, answers from 112 respondents were used in the analysis (2.93%).

The questionnaire consisted of 6 Sections: Introduction, Information regarding the Company, Company as a value provider, Company as a value receiver, Mutual Relationship with Buyers and Suppliers, and Conclusion. The first section focused on providing information regarding the survey, the goal, and the purpose. The second section contained questions regarding the Company—size, subject, etc. The third section contained questions regarding the values which Company provides to its suppliers—which indicators are provided to its suppliers by the Company, and what is its opinion as the provider. The fourth section contained similar questions as the third one, but the Company was supposed to answer the questions from the supplier’s point of view. The fifth section was dedicated to mutual relationships with suppliers and buyers. The last section consisted of thanking the respondents and asking them for consent to process the provided information. The questions connected to the survey can be found in Appendix A.

The enterprises answered the questions from the suppliers’ point of view, i.e., what values are provided to them by their buyers. At the same time, they expressed the importance of the given value creation indicators and their relationship with their buyers.

Within the questionnaires, 21 indicators of value creation for the suppliers were defined. Individual indicators of value creation for suppliers are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Value creation indicators for suppliers.

Respondents were asked to express their perception of the importance of value creation indicators within the questionnaire on a scale from 1 to 5 (1—no importance, 2—more unimportant than important, 3—neutral, 4—more important than unimportant, 5—important). Receiving, i.e., whether the given values are provided to them, the respondents should express yes/no answers.

The mutual relationship of the enterprise (as a supplier—recipient of the value) with its buyers was to be expressed by the respondents on a scale from 1 to 5 (1—completely unsatisfied, 2—more unsatisfied than satisfied, 3—neutral, 4—more satisfied than unsatisfied, 5—completely satisfied).

Descriptive statistics (mainly the average and frequency) are used to evaluate other important data to meet the paper’s objectives. Image processing and data evaluation through graphs and tables are used for better clarity and comprehensibility of the assessed data.

One of the aims of the research is to evaluate the indicators of value creation, precisely their significance, and the force of influence they have on the relationship between supplier and buyer. The Chi-squared test (Wasserstein and Lazar 2016; Ostertagova 2013) is used to evaluate the significance, and the Cramer’s V test determines the variables’ dependence (Bergsma 2013; Marchant-Shapiro 2017). Subsequently, the Rank–Biserial Correlation is used to measure the strength of the association between the indicators and the relationship with buyers. Using the Chi-squared test, it is possible to determine the level of significance of individual indicators for the mutual relationship of the supplier with its buyers through p-value. The given indicator is significant if the p-value is lower than 0.05. The next step is to evaluate the strength of the interdependence between the value creation indicators and the supplier’s relationship with its buyers through Cramer’s V. The closer the value is to 1, the stronger the interdependence is. The Biserial correlation coefficient is an association index between a dichotomous variable and an ordinal variable. This coefficient measures the strength of the association of those two variables in a single measure (from −1 to 1). −1 indicates a perfect negative association, 0 indicates no association, and +1 indicates a perfect positive association.

For a more in-depth analysis of the relationship with buyers and the factors that affect this relationship, we used ordinal logistic regression (OLR). Ordinal regression models belong to generalized linear models, and they are used to predict an ordinal dependent variable, in this case, the enterprise’s relationship with its buyers (B2B), which was determined on a 5—point Likert scale. 1 represented complete dissatisfaction, and 5 complete satisfaction with the relationship. Our model used a logit link function to analyze the ordered categorical data. If the logit link is used, the ordinal regression model may be written in the form as follows (Yatskiv and Spiridovska 2013):

where j indexes the cut-off points for all categories (k) of the outcome variable.

Based on the respondents’ answers, we selected the ten most frequently provided indicators of value (regularity of orders, adherence to business conditions, payment of invoices due date, friendly relationships, recommendation of the enterprise, goods or services to other buyers, business promotion assistance, relationships beyond the contract, joint problem solving, and providing feedback) and used them as input binary variables into the model. We also added as an input to the model the importance of these ten identified value indicators as ordinal categorical variables. In addition, the business of enterprise (production or services) as a binary variable and enterprise size (categorical variable) were used as independent variables in the model.

All the factors mentioned were considered potential determinants affecting the relationship with buyers. However, before creating the model, we decided to test the assumption of multicollinearity using VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) with a threshold of 2.5. Based on the results of this method, the value indicator “Increasing the frequency of orders and increasing the quantity of ordered goods/services together” with its importance was removed from the independent variables. All the tests and OLR were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics software.

4. Results

4.1. Providing Value Creation Indicators to Suppliers

Creating value for stakeholders is important in developing good business relationships, increasing competitive advantage, and securing a market position. Enterprises in the position of suppliers (112 respondents from Slovakia) answered which indicators of value creation are provided to them by their buyers, i.e., on which buyers focus the most when securing good business relations with them as their suppliers. On the other hand, the survey results also identify those indicators of value creation that are not provided to suppliers at all or only to a small extent.

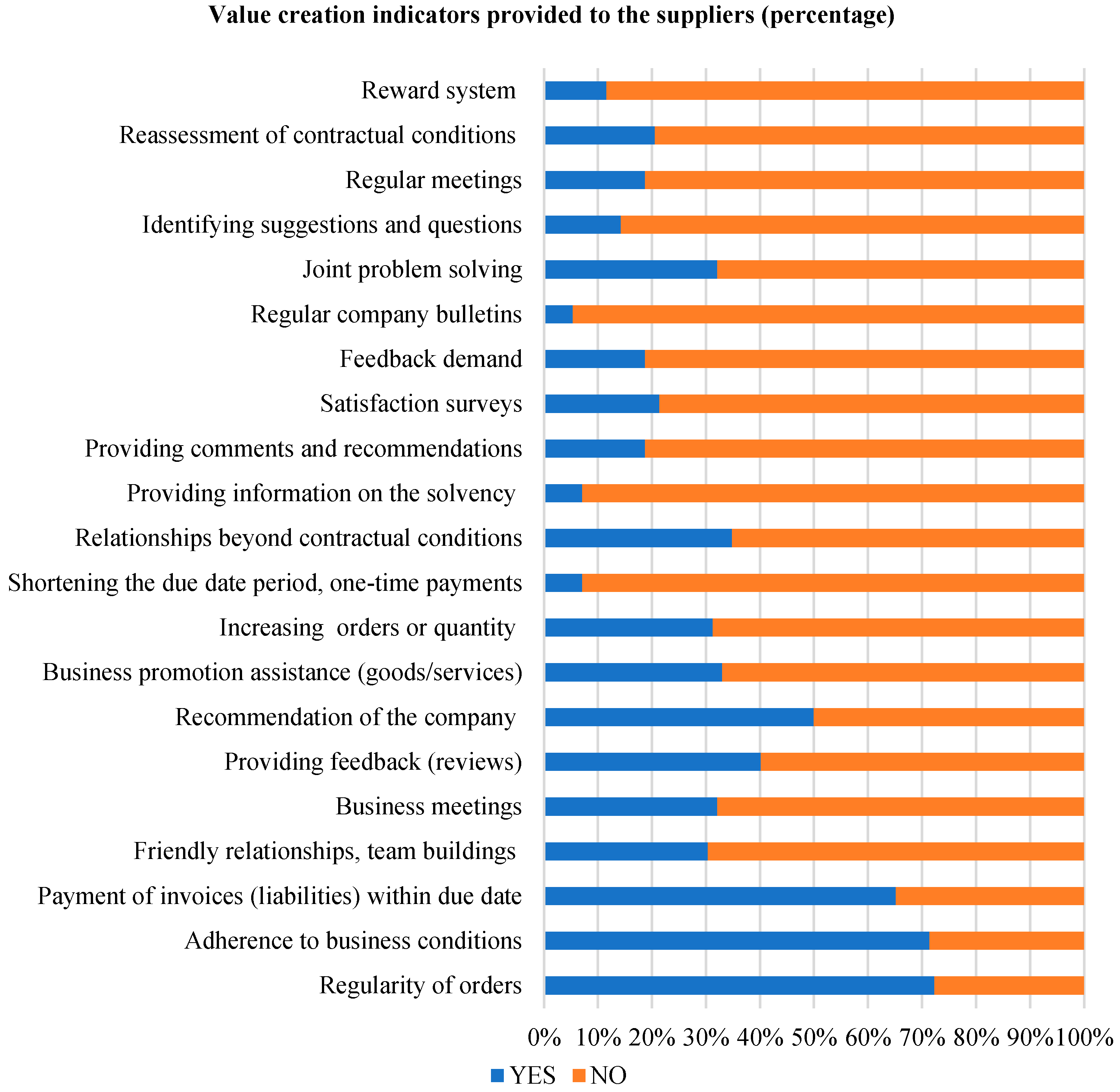

Figure 1 shows that the suppliers are provided the most with an indicator of value creation, which is the regularity of orders. This was indicated by up to 72.32% of respondents. Other frequently provided values are adherence to business conditions (71.43%), payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (65.18%), but also recommendation of the enterprise (goods/services) to other buyers (50.00%). On the contrary, the least provided indicators of value creation include, for example, regular enterprise bulletins, where only 5.36% of respondents answered that the given value is provided to them. Other indicators of value creation, which are provided to a meager extent, are also:

Figure 1.

Value creation indicators provided to the suppliers.

- A reward system in compliance with business conditions (11.61%);

- Provision of information on the enterprise’s solvency (7.14%);

- Shortening of the due date period, one-off payments (7.14%).

4.2. Perception of Received Indicators of Value Creation by the Suppliers

An important factor in providing value to suppliers is not only information on which indicators of value are most provided to suppliers, but the primary information is suppliers’ perception of these indicators. In order to meet the needs of suppliers and the possibilities of the enterprise (what they can provide to these suppliers, i.e., what are their capacity and financial options), it is crucial to know the suppliers’ preferences. Businesses in the position of suppliers answered the questions regarding the importance they attach to individual indicators of value creation. Based on this information, it is possible:

- To compare whether they are provided with the values important to suppliers;

- To identify indicators that should enterprises (buyers) focus on more when creating and providing value to suppliers;

- To identify indicators that are provided to suppliers unnecessarily. Thus, enterprises (buyers) waste their time, financial, and capacity resources.

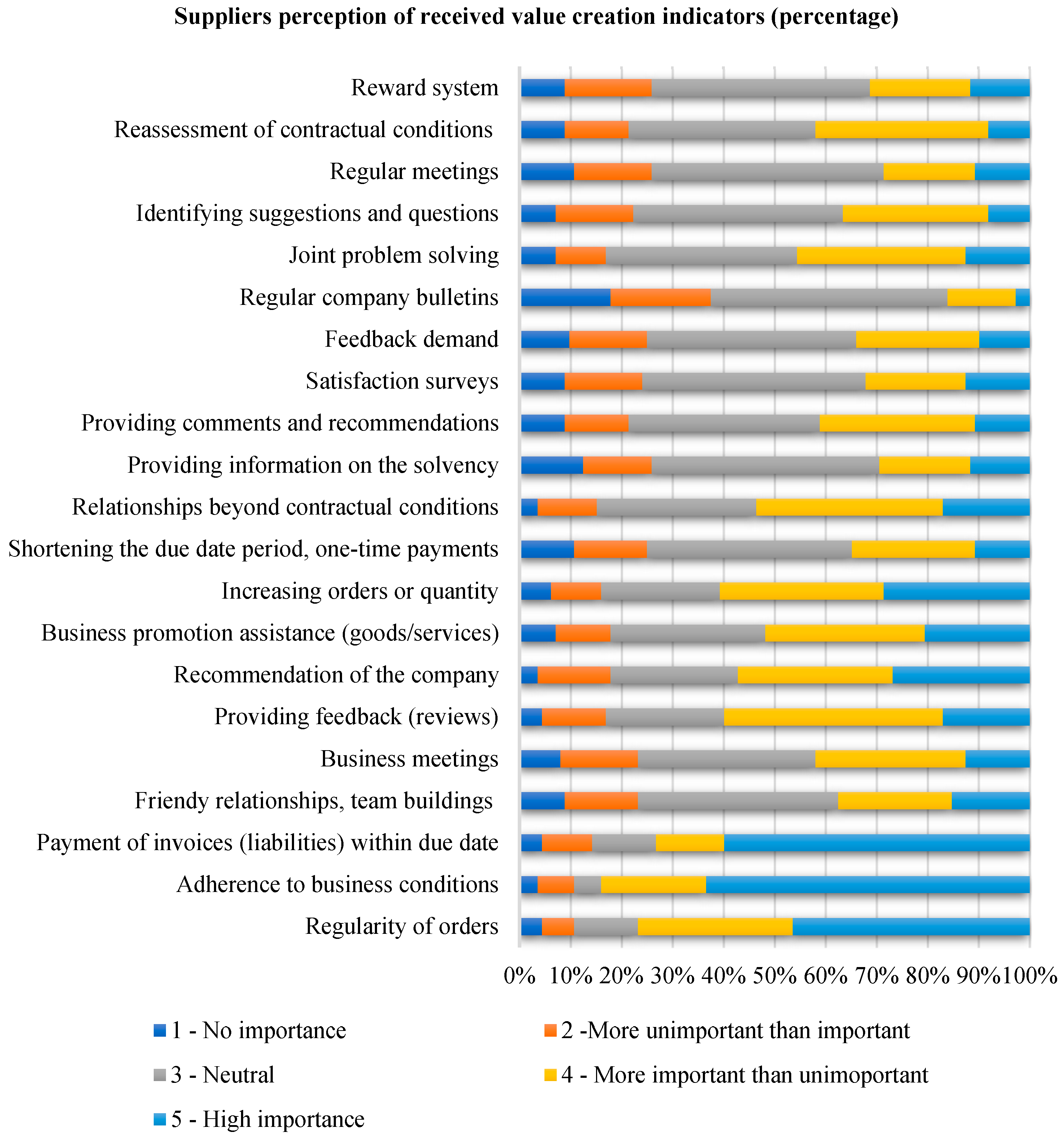

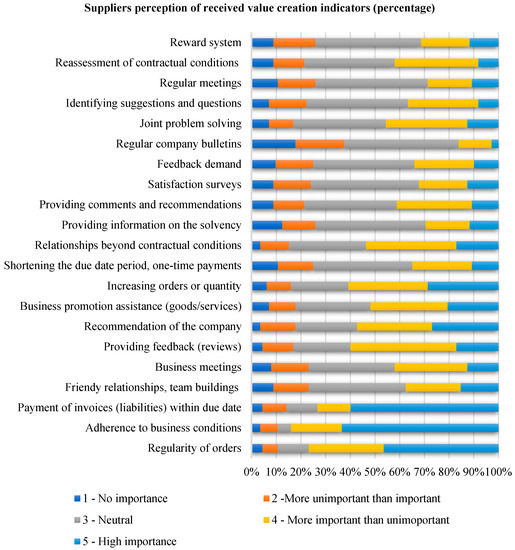

Enterprises (112 respondents from Slovakia) expressed the importance of individual indicators on a scale from 1 (no importance) to 5 (high importance). Figure 2 represents the importance of individual indicators ascribed to them by enterprises as recipients of value-creation indicators. The indicator to which enterprises in the position of suppliers attach the highest importance is adherence to business conditions. Up to 83.93% of respondents said that the indicator is more important than unimportant or highly important. Other indicators that are important for enterprises in the position of suppliers or more important than unimportant are:

Figure 2.

Suppliers’ perception of received value creation indicators.

- the regularity of orders (76.79%);

- payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (73.21%);

- increasing the frequency of orders, increasing the quantity of ordered goods/services (60.71%).

On the other hand, the lowest importance or neutrality was attributed by enterprises in the position of suppliers to regular bulletins (83.93%). Other indicators that are more unimportant than important, neutral, or of no importance to the suppliers are the provision of information on the enterprise’s solvency (70.54%), regular (monthly, quarterly, semi-annual, annual) meetings (71.43%), a system of rewards in compliance with business conditions (68.75%).

4.3. Significance, Dependence and Association of Individual Value Creation Indicators and the Supplier’s Relationship with Buyers

Cramer’s V and Chi-squared tests were used to evaluate the significance and dependence of indicators of value creation and the supplier’s relationship with its buyers. Table 3 shows the results of Cramer’s V and Chi-squared test. Indicators for which the value of p is less than 0.05 are highlighted, i.e., these indicators are significant and affect the supplier’s relationship with its buyers. The higher the value of Cramer’s V, the greater the dependence, i.e., dependence between indicators and the supplier’s relationship with its buyers.

Table 3.

Cramer’s V and Chi-squared test.

Based on the results shown in Table 3, significant indicators are identified. These indicators impact the supplier’s relationship with its buyers. The indicators of the highest importance include:

- The regularity of orders;

- Payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date;

- Friendly relationships;

- team buildings;

- adherence to business conditions.

Rank Biserial Correlation was used to determine the association between the indicators and the supplier’s relationship with its buyers. In all cases, the Rank–Biserial Correlation coefficient equals +1, which means that there is a perfect positive association between all the indicators and the supplier’s relationship with its buyers (see Table 2).

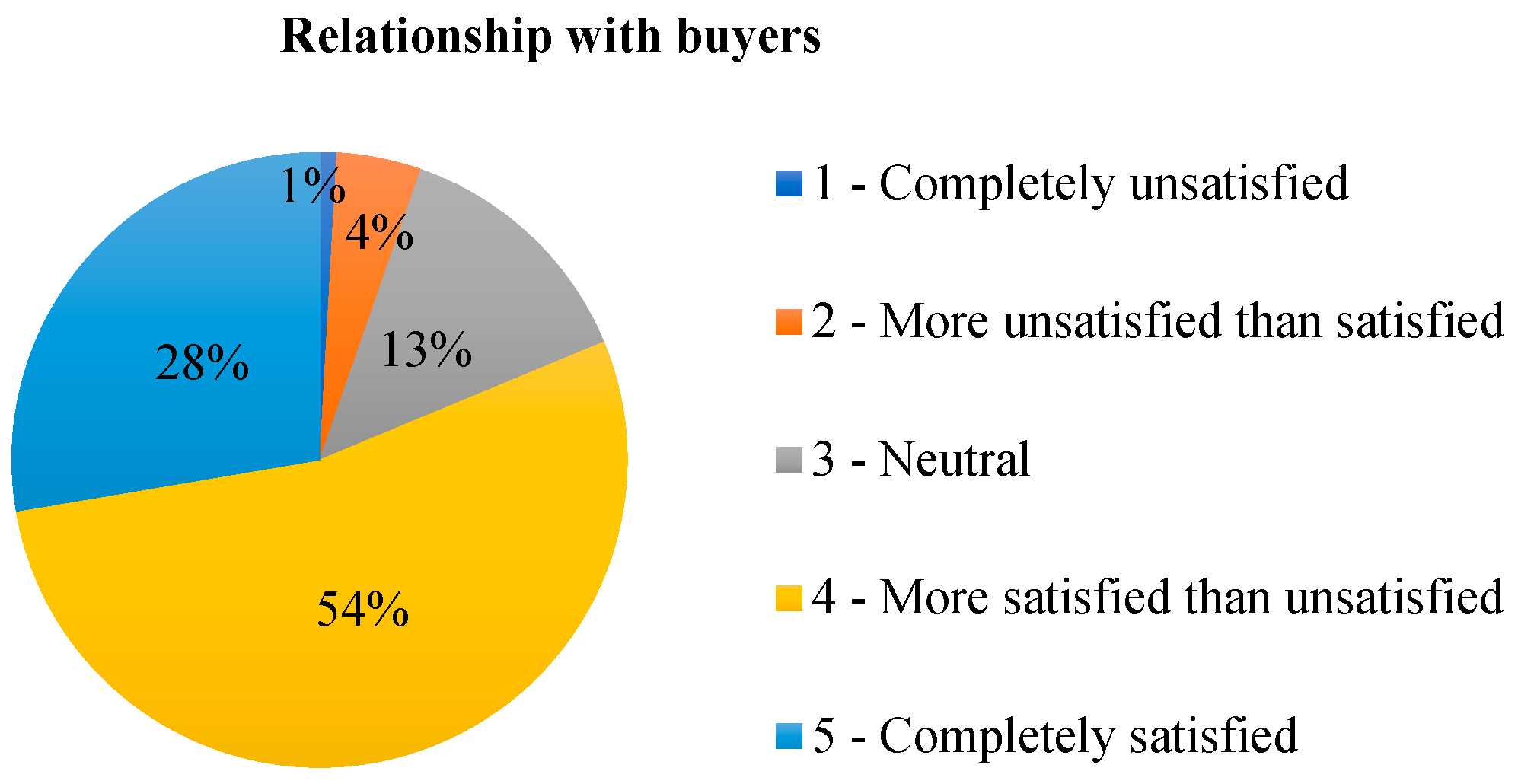

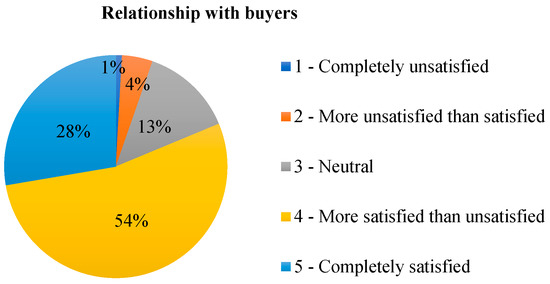

These indicators impact the enterprise’s relationship (which is in the supplier’s position) with its buyers. Figure 3 shows the answers of 112 respondents who rated their relationship with buyers on a scale from 1 to 5. The average rating is 4.03, i.e., enterprises have a relationship with their buyers that is more satisfied than unsatisfied.

Figure 3.

Enterprise’s satisfaction with the relationship with its buyers.

4.4. Model’s Results

Using ordinal logistic regression, we analyzed the influence of the subject and the size of the enterprise, the provided indicators of value, and their importance on the enterprise’s relationship with its buyers. Based on the Pearson goodness-of-fit (χ2(371) = 324.389, p = 0.961), it can be stated that the model is a good fit for the observed data. Table 4 shows the parameter estimates of the model. As can be seen, at the significance level of alpha = 0.05, the enterprise’s relationship with customers or buyers is influenced by the regularity of orders, friendly relationships, and team building with business partners. Regarding value indicators’ importance, no factor was identified as significant.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates of the ordinal regression model.

As shown in the model results, enterprise size and subject do not significantly impact relationships with buyers. Regarding value indicators provision, the odds of enterprises that did not indicate the provided value indicator “Regularity of orders” is 0.139 (95% CI, Wald χ2(1) = 9.996, p = 0.002) times that of enterprises that selected this indicator as received. The second significant factor in this category is the indicator “Friendly relationships, teambuildings. The odds of enterprises that do not have friendly relationships with their business partners was 0.330 times that of enterprises with friendly relationships, a statistically significant effect, χ2(1) = 4.544, p = 0.033.

4.5. Key Findings

- The most provided value creation indicators to suppliers are regularity of orders (72.32%), adherence to business conditions (71.43%), and payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (65.18%);

- The indicators to which enterprises in the position of suppliers attached the highest importance are adherence to business conditions (83.93%), the regularity of orders (76.79%), and payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (73.21%);

- The indicators to which enterprises in the position of suppliers attached the lowest importance are regular bulletins (83.93%), provision of information on the enterprise’s solvency (70.54%), and regular (monthly, quarterly, semi-annual, annual) meetings (71.43%);

- Indicators that impact a supplier’s relationship with its buyers are the regularity of orders, payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date, friendly relationships, teambuilding, and adherence to business conditions;

- A total of 28% of suppliers are completely satisfied with their relationship with their buyers. 54% of suppliers are more satisfied than unsatisfied, 13% consider their relationship neutral, 4% are more unsatisfied than satisfied, and just 1% indicated that they are completely unsatisfied with their relationship with buyers.

- Enterprise size and enterprise subject do not have a significant impact on relationships with buyers;

- Enterprises that receive orders regularly have better relationships with their suppliers. Enterprises that do not have a friendly relationship with their buyers are less satisfied with their overall relationship with them.

5. Discussion

The research aims to identify the value creation indicators provided to suppliers and to approach their perception, i.e., what importance they attach to them. Suppliers build relationships with their buyers based on the values provided to them. The research made by State of Flux (2022) highlights collaboration as one of the drivers important in building relationships with suppliers. The survey was conducted in 2022 and included feedback from 424 respondents representing 304 companies across continents.

The paper’s subject is also to determine whether the suppliers are provided with precisely the values that are important to them. Based on the research, it was possible to answer the research questions defined at the beginning.

Answers to research questions:

- Which value creation indicators are significant in building a supplier’s relationship with its buyers?

Four of the 21 indicators were identified based on the Chi-squared test, which are significant and thus impact the enterprise’s relationship with its buyers (see Table 3). All these indicators also have the highest Cramer’s V coefficient and positive Rank–Biserial Correlation coefficient. Based on this research, enterprises that want to build a relationship with their suppliers should provide the given indicators of value creation. When creating a relationship with suppliers, enterprises should focus mainly on the following:

- regularity of orders;

- adherence to business conditions;

- payment of the invoice (liabilities) within the due date;

- friendly relationships, and team building.

Thanks to determining the significance of the given indicators, it was possible to focus the research on selected indicators that impact the relationship between the supplier and its buyers.

One of the significant indicators in building a supplier’s relationship with its buyers is the regularity of orders. However, based on the research conducted by State of Flux (2022), at least 55% of enterprises reported major challenges in forecasting demand and planning. On the other hand, 60% of companies increased their level of engagement with suppliers and joint planning activities. This fact also points to the importance of collaboration in choosing significant value-creation indicators.

- 2.

- How do enterprises (suppliers) evaluate their relationship with their buyers?

Based on the Cramer’s V and Chi-squared test, it was possible to determine significant and dependent indicators that affect the enterprise’s relationship (as a supplier) with its buyers. Enterprises have defined their relationship with buyers (see Figure 3). A total of 81.25% of enterprises (suppliers) are satisfied with their relationship with their buyers. Alternatively, for them, their mutual relationship is more satisfying than unsatisfying. However, 18.75% of respondents (suppliers) stated that they have a neutral relationship with their buyers. Alternatively, their mutual relationship is unsatisfying or more unsatisfying than satisfying. In order for customers (buyers) to improve the perception and opinions of suppliers on their interrelationships, buyers should focus on four significant indicators and find a way to provide the given value-creation indicators to their suppliers. Creating a good relationship, trust, and cooperation are the fundamental pillars of long-term business relationships, mutual respect, joint progress, and growth of both business partners, buyers, and suppliers. The research conducted by the State of Flux (2022) showed the point of view of enterprises (buyers) in case what benefits they gained from building the relationship with their suppliers. Most of the respondents, 73%, stated risk reduction as the benefit they gained. The other answers were service level (58%), cost avoidance (56%), continuous improvement and innovation (56%), collaborative problem-solving (52%), increasing supplier commitment (50%), cost reduction (49%), and others.

- 3.

- Which value creation indicators are provided to the suppliers the most?

Based on the research (see Figure 1), nine value creation indicators were selected, which are provided to suppliers the most. The given indicators are:

- Regularity of orders (72.32%);

- Adherence to business conditions (71.43%);

- Payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (65.18%);

- Recommendation of the enterprise (goods/services) to other buyers (50.00%);

- Providing feedback (40.18%);

- Relationships beyond contractual terms, willingness to communicate in solving problems (34.82%);

- Business promotion assistance (goods/services) (33.04%);

- Business meetings (32.14%);

- Joint problem-solving (32.14%).

When comparing the value creation indicators that are significant in building a relationship with buyers and those that are actually provided, it is visible that not all significant indicators are provided to the suppliers or are provided to a low extent. It is these indicators that buyers should focus on when providing value to suppliers. Such an indicator is, for example, friendly relationships, and team building, which are provided to only 30.36% of respondents (suppliers). The research from the State of Flux (2022) provided information regarding financial benefits delivered above and beyond contracted spending for their critical and strategic suppliers. A total of 43% of respondents said they do not capture/monitor these financial benefits. On the other hand, 46% of respondents keep track of this matter.

- 4.

- Which value creation indicators are the most important for the suppliers?

Based on the research (see Figure 2), nine indicators of value creation were selected, which most of the respondents (suppliers) stated were important for them or more important than unimportant. The given indicators of value creation include:

- Adherence to business conditions (83.93%);

- Regularity of orders (76.79%);

- Payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date (73.21%);

- Increasing the frequency of orders, increasing the number of ordered goods/services (60.71%);

- Providing feedback (59.82%);

- Recommendation of the enterprise (goods/services) to other buyers (57.14%);

- Relationship beyond contractual conditions (53.57%);

- Business promotion assistance (goods/services) (51.79%);

- Joint problem solving (45.54%);

- Reassessment of contractual conditions, changes based on mutual communication (41.96%).

When comparing the value creation indicators significant in building a relationship with buyers and those to which suppliers attach the highest importance, it is clear that not all significant indicators are among the most important for suppliers. Such an indicator is, for example, friendly relationships and team building. Only 37.50% of respondents indicated that the given indicator of value creation is important for them or more important than unimportant.

In order for enterprises (buyers) to know what indicators are significant for their suppliers, it is important to gather feedback from them. Based on the research by State of Flux (2022), 55% of respondents gather feedback through ad-hoc informal conversations with key suppliers, 41.7% have documented conversations, and 19.7% use one-directional questionnaires. The rest use 360-degree feedback or engage a third party. 15% of respondents stated that they do not gather any feedback from suppliers.

- 5.

- Are suppliers provided with precisely the values they consider most important?

By comparing the results of the value creation indicators that are provided to suppliers and those that are important to suppliers, it is possible to establish the following:

- (a)

- Indicators provided to suppliers which are also important for them, i.e., the given indicators of value creation are perceived by suppliers, and they attach high importance to them;

- (b)

- Indicators provided to suppliers which are not important for them, i.e., suppliers do not perceive the indicators; they are not important to them. These indicators of value creation are provided by enterprises (buyers) in building a relationship with suppliers unnecessarily and thus waste financial, capacity and time resources;

- (c)

- Indicators that are not provided to suppliers but are important for them. I.e. value creation indicators that enterprises (buyers) should focus on when building a relationship with suppliers.

When comparing the list of the most provided indicators and the list of most important indicators for suppliers (i.e., they attach importance to them or are more important to them than unimportant), it is clear that suppliers are provided with important indicators. However, it is crucial to determine the extent to which these value-creation indicators are provided to the enterprise (supplier).

An indicator that is provided to suppliers and which is also important for suppliers is, for example, the regularity of orders, where 76.79% of respondents stated that the indicator is important to them. Almost the same percentage of respondents indicated that the value creation indicator was also provided to them (72.32%).

Among the important indicators provided to the suppliers but not to the same extent is, for example, adherence to business conditions. Up to 83.93% of respondents stated that the indicator is important to them. However, this value is provided only to 80 respondents (71.43% of suppliers). Such indicators, which are important for suppliers but not provided to them to the same extent, are:

- Payment of invoices (liabilities) within the due date;

- Recommendation of the enterprise (goods/services) to other buyers;

- Increasing the frequency of orders, increasing the quantity of ordered goods/services;

- Providing feedback;

- Relationship beyond contractual terms.

Enterprises (buyers) should focus on these indicators of value creation (stated above) when creating value. The given indicators are important for suppliers but are not provided to them. In these cases, a space to provide value and thus build or improve mutual relations with suppliers is created. If enterprises (buyers) do what is essential for suppliers, they will create value for them. Consequently, if enterprises provide value to suppliers and these suppliers perceive the provided value, then the process helps build long-term sustainable relationships with suppliers, economic growth, and gain a competitive advantage for all stakeholders in the process.

From the literature review, it appears that there is no such list of indicators for suppliers which can impact the mutual relationships between the enterprises and their suppliers. Therefore, the list can contain even more indicators that can be significant for the research.

It is difficult to determine the universal methodology as every enterprise is unique, has set specific requirements for inputs and processes, and has different resources and goals they want to achieve.

The response rate of the survey was low, the same as the extent to which respondents participated in answering open questions. These insights can be considered as limitations of this study.

6. Conclusions

Enterprises should focus on identifying suppliers’ opinions, attitudes, goals, and needs before providing value to them. Only then will the enterprise be able to identify a value that will meet the supplier’s requirements, thus being important to the supplier. The enterprise’s resources used in this way (to identify value and method of provision) will become effective in building a relationship with the supplier.

Generally, enterprises (suppliers) are satisfied with their relationship with buyers. This fact was indicated by 81.25% of respondents. However, 18.75% of suppliers have a neutral relationship with their buyers, or their mutual relationship is unsatisfying or more unsatisfying than satisfying. Based on the research, enterprises that want to build a relationship with their suppliers should focus on providing the following indicators: regularity of orders, adherence to business conditions, payment of the invoice (liabilities) within the due date, friendly relationships, and team building. The research also shows which value creation indicators are provided to the enterprises (suppliers) the most, which are the most important for the suppliers, and if the suppliers are provided with precisely the values they consider most important.

Based on the research, it can be stated that suppliers are provided with indicators of value creation to a lesser extent than they attach importance to them. The research did not identify the value creation indicators provided to suppliers, but suppliers do not see any importance in them. In most cases, suppliers attach importance to the indicators, but the given value-creation indicators are provided to them to a lesser extent. This points to the fact that enterprises (buyers) do not provide suppliers with values that suppliers do not perceive. The result is rather the inadequacy of meeting the needs of suppliers and identifying their opinions or attitudes. On the one hand, this can be seen as an advantage for businesses (buyers), as they still have room to improve the conditions provided to suppliers. However, it points to the fact that businesses (buyers) do not use value-providing opportunities to create better long-term and sustainable relationships with suppliers.

The paper points out the importance and significance of individual value-creation indicators for Slovak enterprises, as well as the important connection between the value-creation process and building sustainable long-term relationships.

This paper is a preparation for further research, which should focus on the next step in providing value to suppliers. The next step is identifying the suppliers’ views, preferences, needs, frustrations, and objectives and determining how to deliver value to the suppliers. Identifying individual value-creation indicators is one section in the comprehensive value-creation process. The whole process should help enterprises to build and maintain sustainable, long-lasting relationships with their suppliers. The value-creating process should be consequently united and linked into a clear visual model for a better understanding of the enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., E.M. and M.Ď.; methodology, D.K. and M.Ď.; data collection, D.K.; validation, D.K. and E.M.; software, E.M.; writing-original draft preparation, D.K., M.Ď. and E.M.; writing-review and editing, D.K., M.Ď. and E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper has been written with the support of VEGA: 1/0273/22—Resource efficiency and value creation for economic entities in the sharing economy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researcher.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

For the purpose of the paper, the questions related to the survey were selected and added to Appendix A.

| Question | Answer |

| What size category does your company belong to? | Micro—Small—Medium—Large |

| To which category does your company belong to? | Manufacturing company—Service provider |

| Does your company have suppliers? | Yes—No |

| Does your company have buyers (businesses) who are not final customers (consumers)? | Yes—No |

| What value (indicators) does your company provide to its suppliers? Please select from the following indicators. | List of the value-creation indicators (see Table 1) |

| What value (indicators) do your buyers (businesses) provide to your company? Please select from the following indicators. | List of the value-creation indicators (see Table 1) |

| What importance does your company see as a recipient of value in the individual indicators stated below (please see Table 1)—related to the previous question? Express the importance on a scale of 1—no importance to 5—high importance. | 1—No importance, 2—More unimportant than important, 3—Neutral, 4—More important than unimportant, 5—Hight importance |

| How would your company characterize the mutual relationship with its buyers (businesses) and suppliers? Express the satisfaction on a scale from 1 to 5, where the mutual relationship is represented by 1—the company is completely unsatisfied with the mutual relationship to 5—the company is completely satisfied with the relationship. | Suppliers—Buyers (Businesses) 1—Completely unsatisfied, 2—More unsatisfied than satisfied, 3—Neutral, 4—More satisfied than unsatisfied, 5—Completely satisfied. |

References

- Abdelkafi, Nizar, and Karl Tauscher. 2016. Business Models for Sustainability from a System Dynamics Perspective. Organization and Environment 29: 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbarlou, Sedegh, Suzanne Wilkinson, and Seosamh B. Costello. 2017. Exploring construction client values and qualities: Ate these two distinct concepts in contruction studies? Built Environment Project and Asset Management 15: 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburger, Adam M., and Harborne Stuart. 1996. Value based business strategy. Journal of Economics and management Strategy 5: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsma, Wicher. 2013. A bias correction for Cramer’s V and Tschuprow’s T. Journal of the Korean Statistical Society 42: 323–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BSI. 2014. BS EN 1325:2014 Value Management, Vocabulary. Terms and Definitions. London: British Standards Institution. [Google Scholar]

- BSI. 2020. BS EN 12973:2020 Value Management. London: British Standards Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Sinead, Benn Lawson, and Daniel R. Krause. 2011. Social capital configuration, legal bonds and performance in buyer-supplier relationships. Journal of Operations Management 29: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Hee Sung, and James T. O’Connor. 2005. Optimizing implementation of value management process for capital projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 131: 239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodasova, Zuzana, Alžbeta Kucharcikova, and Zuzana Tekulova. 2015. Impact analysis of production factors on the productivity enterprise. Paper presented at International Scientific Conference on Knowledge for Market Use—Women in Business in the Past and Present, Olomouc, Czech Republic, September 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chodasova, Zuzana, and Zuzana Tekulova. 2016. Monitoring of competitiveness indicators of the controlling enterprise. In Production Management and Engineering Sciences. Paper presented at International Conference on Engineering Science and Production Management (ESPM), Tatranská Štrba, Slovakia, April 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Climent, Ricardo Costa, and Darek M. Haftor. 2020. Value creation through the evolution of business model themes. Journal of Business Research 122: 353–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, Simon, and Robert E. Wright. 2011. The 50 Economic Indicators That Really Matter. London: HarperCollins Publishes Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Roger H., and Adam J. Davies. 2011. Value Management—Translating Aspirations into Performance. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth, Andrej. 2013. Teória Percepcie. Trnava: Filozofická Fakulta Trnavskej Univerzity v Trnave. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert, Andreas, Michael Kleinaltenkamp, and Vishal Kashyap. 2019. Mapping value in business markets: An integrative Framework. Industrial Marketing Management 79: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, Ingmar, Florian Dost, Alejandro Schonhoff, and Michael Kleinaltenkamp. 2015. Which types of multi-stage marketing increase direct customer’s willingness-to-pay? Evidence from a scenario-based experiment in a B2B setting. Industrial Marketing Management 47: 175–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, Devi R., and Ryan Tadhg Charleton. 2018. Nuances in the interplay of competition and cooperation: Towards a theory of coopetition. Journal of Management 44: 2511–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedhart, Marc, Tim Koller, and David Wessels. 2020. Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, 7th ed. Brussels: McKinsey & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, Christian, and Pekka Helle. 2010. Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: Conceptual foundation and metrics for mutiual value creation. Journal of Service Management 21: 564–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, David, Greet Peersman, Deborah Rugg, and Eva Kiwango. 2010. UNAIDS. An Introduction to Indicators. UNAIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Fundamentals. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/8_2-Intro-to-IndicatorsFMEF.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Hart, Maureen. 1999. Guide to Sustainable Community Indicators, 2nd ed. North Andover: Hart Environmental Data. [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, Milos, Gabriela Pajtinkova-Bartakova, Silvia Lorincova, Hubert Palus, Andrej Pinak, Martina Lipoldova, Martina Krahulcova, Nikola Slastanova, Katarina Gubiniova, and Kristina Klaric. 2019. Sustainability in marketing through customer relationship management in a telecommunication company. Marketing and Management of Innovations 4: 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, Milos, Silvia Lorincova, Lenka Lizbetinova, and Gabriela Pajtinková Bartakova. 2017. Cluster Analysis Used as the Strategic Adventage of Human Resource Management in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in the Wood-Processing Industry. Bioresources 12: 7884–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, Lars, and Xiaobei Wang. 2021. Resource fundles and value creation: An analytical Framework. Journal of Business Research 134: 720–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jánošová, Patricia. 2021. Marketing Strategy and Practice Sustainable activities in manufacturing enterprises: Consumers‘ expectations. Marketing Strategy and Practice 12: 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG Study. 2016. Úrad podpredsedu vlády SR pre investície a informatizáciu. Metodologická príručka pre hodnotenie synergických efektov EŠIF v kontexte stratégie Európa 2020. Available online: https://www.partnerskadohoda.gov.sk/data/files/1187_metodologicka-prirucka-pre-hodnotenie-synergickych-efektov-v-kontexte-strategie-europa-2020.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Kucharcikova, Alzbeta, and Martin Miciak. 2017. Human Capital management in Transport Enterprise. Paper presented at 18th International Scientific Conference on LOGI, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic, October 19. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Mei Yung, and Anita M. M. Liu. 2003. Analysis of value and project goal specificity in value management. Construction Management and Economics 21: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Lode, and Hongtao Zhang. 2008. Confidentiality and information sharing in supply chain coordination. Management Science 54: 1467–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yadong. 2009. From gain-sharing to gain-generation: The quest for distributive justice in international joint ventures. Journal of International Management 15: 343–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandt, Tobias. 2018. Dependence in Buyer-Supplier Relationships. Koln: Edition KWV. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Shapiro, Theresa. 2017. Chi-Square and Cramer’s V: What Do You Expect? In Statistics for Political Analysis: Understanding the Numbers. London: SAGE Publications, chp. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Luis L., Violina P. Rindova, and Bruce E. Greenbaum. 2015. Unlocking the hidden value of concepts: A cognitive approach to business model innovation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 9: 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Robert M., and Shelby D. Hunt. 1994. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing 58: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertagova, Eva. 2013. Aplikovaná štatistika. Košice: Equilibria, p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Post, James E., Lee E. Preston, and Sybille Sachs. 2002. Managing the extended enterprise: The new stakeholder view. California Management Review 45: 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusa, Petr, Stefan Jovčić, Josef Samson, Zuzana Kozubíková, and Ales Kozubík. 2020. Using a non-parametric technique to evaluate the efficiency of logistics company. Transport Problems 15: 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulles, Niels J., Holger Schiele, Jasper Veldman, and Lisa Huttinger. 2016. The impact of customer attractiveness and supplier satisfaction on becoming a preferred customer. Industrial Marketing Management 54: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanova, Lubica, Andrea Sujova, and Pavol Gejdos. 2019. Improving the Performance and Quality of Processes by Applying and Implementing Six Sigma Methodology in Furniture Manufacturing Process. Drvna Industrija 70: 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieth, Patrick, Sabrina Schneider, Thomas Clauss, and Daniel Eichenberg. 2019. Value drivers of social businesses: A business model perspective. Long Range Planning 52: 427–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Flux. 2022. Global SRM Research Report—Building Resilienc. Available online: https://ebooks.stateofflux.co.uk/link/627739/112/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Takeishi, Akira. 2002. Knowledge partioning in the interfirm division of labor: The case of automotive product development. Organization Science 13: 321–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekulova, Zuzana, Marian Kralik, and Zuzana Chodasova. 2016. Environmental policy enterprise as a competitive advantage. Smart city 360. Paper presented at the second EAI International Summit, Bratislava, Slovakia, November 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarcikova, Emese, Olga Ponisciakova, and Ivan Litvaj. 2014. Key performance indicators and their exploitation in decision-makig proces. Paper presented at the 18th International Conference on Transport Means, Kaunas, Lithuania, October 23–24; pp. 372–75. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Frederick. 1990. The Meaning of Value: An Economics for the Future. New Literary History 21: 747–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, Frederik G. S., R. Van der Lelij, Holger Schiele, and N. H. J. Praas. 2021. Mediating the impact of power on supplier satisfaction: Do buzer status and relational conflict matter? Internationl Journal of Production Economics 239: 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, Ronald, and Nicole A. Lazar. 2016. The ASA Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. American Statistician 70: 129–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, Marc-Andree, and Kirana Chomkhamsri. 2012. Selecting the Environmental Indicator for Decoupling Indicators. Paper presented at the Proceeding in Ecobalance International Conference, Yokohama, Japan, November 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yatskiv, Irina, and Nadezda Spiridovska. 2013. Application of ordinal regression model to analyze service quality of Riga coach terminal. Transport 28: 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Yu-Xiang, and Shiu-Wan Hung. 2017. The influences of suppliers on buyer market competitieness: An opportunism perspective. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 32: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Kevin Zheng, Qiyuan Zhang, Shibin Sheng, En Xie, and Yeqing Bao. 2014. Are relational ties always good for knowledge acquisition? Buyer-supplier exchanges in China. Journal of Operations Management 32: 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).