Abstract

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are increasingly called to substantiate their impact on society in terms of inclusivity and social sustainability, as prioritized in the pursuit of the “Third Mission” (TM). Today, HEIs are confronted with the demand to ensure refugees’ inclusivity. However, how administrative and teaching staff enact such change within the organization to match the TM goals is under-investigated. This study explores the adoption of the European Qualification Passport for Refugees (EQPR) as an instrument for universities to pursue the TM in Italy. By adopting a theoretical sense-making approach, we find that the individual role of the staff in fostering organizational change depends on the adopted “emergent” approach to change and on internal factors, such as individual perceptions and experiences. This study contributes to the literature by showing contradictory aspects of the HEIs’ pursuit of the TM. It sheds light on the interplay between different dimensions and grounded processes of sense-making.

1. Introduction

The world is living in times of tremendous change and is experiencing a growing concern for possible adverse outcomes of organizations’ actions that have led to increasing social inequalities, environmental damage, and economic disparities. As a result, there is a growing consensus that organizations should behave responsibly and be oriented towards sustainability and sustainable development goals. Conceiving social responsibility for organizations contributes to building different “spaces of hope”—a relational phenomenon precisely created across a range of human and nonhuman materialities (Anderson and Fenton 2008), to cope with our time’s dramatic changes and complexity.

From an organizational standpoint, embracing sustainability comprehensively implies starting a radical organizational change in search of creative organizational forms and innovative organizational solutions to promote dialogical spaces and nurture employees’ participation in the change process. In fact, people are also confronting a growing sense that “becoming active” is needed (Hjorth and Steyaert 2021; Janssens and Zanoni 2021). From an organizational perspective, this sense of participation is pivotal to driving organizational change. Managing change requires a consideration of its effects on the interpretive schemes of organization members and understanding the action of attributing sense to a flow of circumstances (Weick 1995).

Within the grand challenges of our time, the social inclusion of disadvantaged groups of people is one of the most relevant. In light of the recent revival of migration flows (e.g., in the EU, +18% in 2021, compared to 2020; immigrants represent 5.3% of the overall population) (Eurostat 2023), the inclusion of migrants and refugees is very high on the political agenda. In this context, the Higher Education sector plays a relevant role in fostering social inclusion and diversity, as highlighted by the Agenda 2030 (United Nations 2015), the Incheon Declaration for Education 2030 (UNESCO 2015), and its Education 2030 Framework for Action. Moreover, in 2017, the European Union, with its “Renewed Agenda for Higher Education,” stressed that building inclusive and connected Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) must be a strategic priority. Indeed, including all learners and ensuring everyone has an equal and personalized opportunity for educational progress is still a challenge in almost every country. Inclusivity in higher education has become a substantial part of HEIs’ “Third Mission” (TM), which has been ambiguously defined as “a contribution to society” (Abreu et al. 2016; Urdari et al. 2017).

The literature on the TM, which is vast and multidisciplinary, has clarified the need for a diversity of practices that evidence the relevance of the TM and its related profound organizational change in universities (Compagnucci and Spigarelli 2020). Moreover, some studies have shown resistance to the new concept of HEIs’ TM. Not all university members are actively involved in the TM (Loi and Di Guardo 2015), calling for better scrutiny of the individual’s attitude towards the TM. Even if micro-foundations issues and individual factors are recognized as critical to knowledge transfer activities (Guerrero and Urbano 2010), still little is known about how individuals in the organizations (administrative and academic staff) enact such organizational change and conceive the university’s TM.

From a dialogic organization perspective, it is interesting to investigate if and how a dialogical form of organizing contributes to the activation and pursuit of the TM by unlocking the pro-activity and dialectics of the meaning-making process that leads to “spaces of hope” at the individual and organizational levels. Affirmative, generative engagement could feed the change process towards a complete pursuit of the TM by unlocking sense-making at the individual level. Sense-making can be viewed as “an instrument through which circumstances are turned into a situation that is comprehended explicitly in words, and that serves as a springboard into action” (Weick et al. 2005, p. 409); it is still unclear how sense-making processes happen at the organizational and individual levels. To tackle inclusivity in HEIs, particular attention should be dedicated to refugees, considered vulnerable subjects to be included since their rights and access to education are often denied.

Complying with these policies related to inclusivity put pressure on universities’ pursuit of the TM and consequently impacted the dimension of change management, defined as “the process of continually renewing an organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers” (Moran and Brightman 2001, p. 111)—in some cases, this was associated with the adoption of the most recent protocols for social inclusion. One of these is the European Qualification Passport for Refugees (EQPR), fostered by the Council of Europe. When deciding to adopt the EQPR, universities face several impacts on their established procedures. Thus, organizational change is required in terms of new competencies, new roles, and new routines.

However, the general change management literature is often centered on the macro dynamics with little attention to the organizational levels (meso and micro) of analysis (Kuipers et al. 2014), considering organizational actors exclusively as recipients of change rather than pro-active change agents (Oreg et al. 2011; Stouten et al. 2018), and focusing exclusively on change models or methods (Stouten et al. 2018; Al-Haddad and Kotnour 2015) and factors of success and failure (Fernandez and Rainey 2006). Therefore, the literature in this domain needs to correctly recognize the complex interplay of different roles and organizational levels that foster change in universities (Kuipers et al. 2014).

This is why our contribution addresses the micro-foundations of change management that delve into dialogic organizing that eases sense-making through the specific case of EQPR adoption to pursue the universities’ TM. We adopt a theoretical sense-making lens to shed light on the individual role of the administrative and academic staff in fostering organizational change to implement the social purpose.

This paper is structured as follows: first, the theoretical background accounts for the well-known relations between organizational change and sense-making while revealing the remaining gaps and, consequently, the proposed research question; second, we present the empirical setting, and we explain the complex context of the EQPR adoption as well as the methodology that we adopted; then, we outline the results, and we discuss them through the theoretical approach; last, we clarify our contributions to the theory and practice while recognizing the limitation of this study.

2. Theoretical Background

From a theoretical point of view, it is well-known that organizational change is about finding new or better ways of using resources and abilities to increase an organization’s capacity to generate value and returns for its stakeholders (Stuart 1998). Competitive pressures, technological evolution, an evolving workforce, and globalization are just some forces that drive organizations to engage and attempt to manage the change needed to sustain their success and existence (Stouten et al. 2018; Al-Haddad and Kotnour 2015). Against this background, private and public organizations constantly strive to align their operations with an evolving environment. Making meaningful and sustainable changes can nonetheless be challenging. Recent reports suggest that executives believe that only one in three organizational change interventions succeed (Jarrel 2017; Jacobs et al. 2013).

Moreover, studies on change management in the private and public sector often present limits in their focus, duly highlighted by well-known literature reviews: (1) the institutional theory and the general change management literature in the public sector prevalently study change dynamics at the macro level (reforms and new policies), with little attention paid to the organizational level of analysis and to the behavioral implications of organizational actors (meso and micro levels) (Kuipers et al. 2014); (2) conversely, looking at the private sector literature, empirical studies at the micro level of analysis focus considerable attention only on individual differences that act as antecedents to commitment and acceptance of the change (Oreg et al. 2011), thus demonstrating that they look at organizational actors exclusively as change recipients and not as pro-active actors of change processes (Stouten et al. 2018); (3) concerning the implementation process, the debate seems to revolve exclusively around the change models or methods (Stouten et al. 2018; Al-Haddad and Kotnour 2015) and the factors of success or failure (Fernandez and Rainey 2006). Consequently, the literature fails to fully understand the complex interplay of different roles and organizational levels that foster change.

Instead, a recent contribution by Hastings and Schwarz (2022) explains how change processes, the activities that enable change, and the leadership of change simultaneously influence the success of the change. The first significant contribution of their work is that they define change leadership as how to guide change processes. In doing so, they refer to individuals’ influence on change evolution (Oreg and Berson 2019). In addition, they outline individuals as leaders, those in formal positions of authority who take responsibility for success, and participants, referring to others who exert influence during change. Finally, they recognize that influence can be top-down and exerted by leaders or bottom-up when exercised by participants (Ford et al. 2021; Yukl 2012).

Second, borrowing an approach proposed by Bushe and Marshak (2009, 2015), they consider change practices from two process-based perspectives. The diagnostic organizational change represents the processes in which organizational states are objectively analyzed and the plans to change them. The dialogic organizational change describes the processes in which action follows dialogue, illustrating conversation-based activities in which new possibilities emerge. Consistently, dialogic processes include disruption, storytelling, and organizational learning, to guide change (Bushe and Marshak 2015; Jabri 2017). In particular, dialogic processes take the perspective that organizations are meaning-making systems where leaders are part of discovering new futures. This dialogic perspective caters to top-down and bottom-up change leadership influences; leaders foster learning environments, and participants contribute to change leadership with ideas, innovations, and new possibilities.

Despite this advance in knowledge, a fundamental problem also emerges. Within the change management discussion, the alignment of change leadership and change process knowledge as either diagnostic or dialogic inherently ignores the possibility that the alternate practice may be more appropriate (Hastings and Schwarz 2022). For the resolution of dichotomies, they modeled the option allied to the highest rate of success: oscillation. This oscillation is typically brief, applied only until the dichotomy is resolved, with leaders then switching back to diagnostic processes (Hastings and Schwarz 2022).

This recent contribution attempts to fill the gap left by much of the change management literature, which poorly recognizes the importance of how change is interpreted at all levels and how sense-making processes guide the implementation of change. Instead, we agree that organizational actors create meanings and construct realities that shape actions and foster change (Eckel and Kezar 2003) through actions and decisions in ongoing meaning-making (Weick 1995). Managing such a change also impacts the interpretive schemes of organization members (Ranson et al. 1980; Bartunek 1984). Moreover, internal factors may also determine new interpretive schemes that alter the perception of identity and the sense-making processes enacted by individuals in performing their roles (e.g., administrative, teaching staff, etc.) (Gioia and Thomas 1996).

In a context of disruptive and unexpected change, organizations increasingly rely on employees that are pro-active, resilient, and self-managing (e.g., Weick and Quinn 1999). The core ability to drive organizational change has become that of easing the internalization of the change by individual employees (O’Hara and Sayers 1996), while the determinants of change success or failure in terms of individual behavior and attitudes towards change are still unclear (Armenakis and Harris 2009). In line with Wrzesniewski et al. (2003), we view the micro-foundations of organizational change based on the meaning that individual employees give to change and to their work (Gover and Duxbury 2018) and to the motivation to take action based on a sense that “becoming-active” is needed (Hjorth and Steyaert 2021; Janssens and Zanoni 2021).

Sense-making is a multidimensional process that individuals engage in while performing their job. Through their wide-ranging critical review of relevant publications in the field of organizational studies, Sandberg and Tsoukas (2015, p. 26) identified and articulated five different essential constituents of the sense-making perspective, namely: sense-making (i) is confined to specific episodes, (ii) is triggered by ambiguous events, (iii) occurs through specific processes, (iv) generates particular outcomes, and (v) is influenced by specific situational factors.

Making sense of complex changes requires that the members of an organization engage in dialogue to elaborate on different perspectives and to co-create a coherent view (Lawrence 2015). Though the importance of “facilitated interaction” between members of organizations is widely acknowledged, the desire to achieve predetermined outcomes easily turns them into monologic rather than dialogic events (Lawrence 2015). In this sense, the a priori openness of the dialogical process is crucial for harnessing participants’ creative efforts in building collective sense-making (Virkkunen 2009).

In 1991, Gioia and Chittipeddi clarified the multidimensional nature of sense-making by introducing sense-giving, later discussed as a sense-making variant undertaken to create meanings for a target audience (Weick et al. 2005). Nevertheless, a certain ambiguity may pervade sense-giving processes, as the individual may intentionally try to persuade others. Still, the effects of sense-giving largely depend on the receivers’ attitude and the complex sense-making environment (Maitlis and Lawrence 2007). Leaders and top managers may significantly facilitate grounded processes of sense-making and sense-giving (Smerek 2011). In the attempt to advance the understanding of such processes, the subsequent sense-making literature has enriched the framework by distinguishing between different processes of sense-making: (i) sense-breaking, a process of disconnecting from previous sense-making narratives (Aula and Mantere 2013); (ii) sense-giving, in the attempt to influence other people’s narratives (Fiss and Zajac 2006; Gioia and Chittipeddi 1991; Maitlis and Lawrence 2007); and iii) sense-taking, i.e., interpreting or evaluating the sense-making narratives of others (Huemer 2012). In the context of education, when sense-breaking, sense-giving, and sense-taking are successful, sense-making favors identity construction, and teachers construct a meaningful conception of self (Pratt 2000; Ravasi and Schultz 2006).

As a case of complex organizational change that bears social values, the universities’ Third Mission (TM) encompasses at least three dimensions: academic knowledge transfer and innovation, university continuing education, and social engagement in local communities contributing to the development of human capital (Mariani et al. 2018). The ambiguity of the concept may depend on three interrelated aspects: (i) the configuration of the activities carried out in a given university, (ii) the degree of its territorial embeddedness, and (iii) the institutional frameworks in which the university operates (Jäger and Kopper 2014). This last aspect seems pivotal to justify the differing degrees of TM engagement since universities are developing the TM as an evolving concept (Vorley and Nelles 2008), engaging in different degrees of organizational change processes. The interplay between such diverse yet complementary processes may have controversial results in pursuing the TM of universities. Different individuals may perceive the TM differently, and institutional pressures may influence the sense-making processes at the individual and organizational levels. As such, a dialogic perspective of organizational change should consider all sense-making dimensions.

Moreover, the social context in which the work is carried out provides crucial elements for the construction of work meaning; the interpersonal sense-making at work (Wrzesniewski et al. 2003) can contribute to organizational change by changing the content of the jobs, the practices, the perception of the selves and the roles. From this perspective, we claim that a micro-foundation of organizational change in the pursuit of the TM is provided by job-crafting (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001; Oldham and Fried 2016) that is related to sense-making.

Petrou et al. (2018) show that employees respond to organizational change communication via job-crafting behaviors. Demerouti et al. (2021) partially confirmed that job-crafting behavior could be an effective way to adapt to organizational change successfully. Nevertheless, these studies have focused on a cognition-based approach to job-crafting, whereas we aim to provide a better understanding of the relationship between sense-making and job-crafting in organizational change.

Thus, the paper aims to answer the following RQs: What are the micro-foundations of a dialogic organizational change? What is the role of sense-making and job-crafting in fostering organizational change for higher inclusivity?

3. Context

Since 1999, in the area of refugee integration, the EU has been working to create a Common European Asylum System and has developed several directives and regulations to establish high standards and stronger cooperation to ensure that asylum seekers are treated equally in an open and fair system (European Commission 2018). Due to many reasons, such as conflict, terror, and persecution at home, political and economic instability of certain regions, or natural disasters, such as floods, hurricanes, and earthquakes, the number of refugees in European countries has increased rapidly in recent years (European Commission 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic has threatened to disrupt the progress in programs for young newcomers and refugees (Ahad et al. 2020), whose access to youth work or non-formal education opportunities has become even more challenging (Stapleton 2020). The recognition of qualifications and the official assessment of their abilities have become fundamental elements of social and educational inclusion. To this aim, the European Qualification Passport for Refugees (EQPR), launched by the Council of Europe, is an instrument that responds to these finalities, being based on Article VII of the Lisbon Recognition Convention on supporting recognition of refugees’ qualifications even in cases when such qualifications cannot be proven through documentary evidence.

Italy has advanced regulation and can be considered a pioneer in EQPR adoption. Paragraph 3 bis of the Legislative Decree n. 18 of 21 February 2014 states that “For the recognition of professional qualifications, diplomas, certificates and other qualifications obtained abroad by the holders of refugee status or subsidiary protection status, the competent administrations should identify appropriate systems of evaluation, validation, and accreditation that allow the recognition of qualifications according to Article 49 of the Decree of the President of the Republic n. 394 of 31 August 1999, even in the absence of certification from the State in which the qualification was obtained when the interested party demonstrates that he or she cannot acquire said certification”. This paragraph, however, remained difficult to be implemented in practice until 2016, when, parallel to the European debate, many activities at the national level started with the aim of developing tools and methodologies for the recognition of qualifications held by refugees, even in cases of partial or missing documentation, to support the indications of the regulation, and to be able to implement them as accepted procedures. In 2016, Italy was chosen by the Council of Europe, together with Greece, Norway, and the United Kingdom, to launch a pilot project, the EQPR, to develop and test a rigorous, effective, and internationally shared methodology for evaluating the qualifications of refugees in cases where the documentation is not sufficient or is absent.

This methodology consists of a written questionnaire submitted by the candidate to reconstruct his study path and an interview marked by a well-defined set of questions carried out by two credential evaluators from different ENIC-NARIC centers. These are entities established on the basis of Article IX.2 of the Lisbon Recognition Convention, and the acronym represents the ongoing collaboration between the European Network of Information Centres in the European Region (ENIC) and the National Academic Recognition Information Centres in the European Union (NARIC).

In the aftermath of the interview, if the evaluators believe that the process has been concluded positively and that there is clear evidence of the qualifications obtained, the document defined as the EQPR is usually issued ten days to three weeks later and is valid for five years. It is a document drawn up by the evaluators, which contains the essential information about the holder of the qualification and the qualifications in his possession, whether they are a final secondary school or post-secondary qualification, information on work experience, and language skills.

After the conclusion of the pilot project in 2017, a second phase of the project was launched, lasting three years, which focused on the implementation and dissemination of the methodology tested and consolidated in the pilot year. In the four years 2018–2021, several EQPR sessions were held in Italy with an action plan under the aegis of the Ministry of University and Research, which involves the CIMEA as the Italian ENIC-NARIC center and the Italian HEIs that adhere to the National Coordination for the Evaluation of Refugee Qualifications (CNVQR). CNVQR is an informal network of administrative experts who operate inside HEIs and deal with the recognition of qualifications and share evaluation procedures, problem cases, sources of information, and methodological practices. The active participation of Italian HEIs in the process and the reliability of the EQPR procedure have been critical to the use of the EQPR as a tool for the enrolment of refugees with partial or missing documentation, as HEIs are autonomous in terms of recognition of qualifications. To date, 200 interviews have taken place in Italy, 140 EQPRs were issued, 49 refugee students have enrolled in Italian HEIs hold the EQPR, and 8 have enrolled in single courses.

Therefore, the EQPR can be considered a game changer (Finocchietti and Bergan 2021) since it shifts the concept of qualifications, spotlighting the knowledge, understanding, competencies, and abilities acquired; it can provide new perspectives when it comes to transforming HEIs.

4. Method

Following the Gioia Methodology (Gioia and Thomas 1996), we have adopted a qualitative, explorative approach in our research. We chose to engage with EQPR managers and scholars of Italian universities, considered knowledgeable experts (Gioia et al. 2013), to gain in-depth insights into their personal experiences to understand the processes by which organizing and organization unfold. Because experts’ mental models tend to be richer in terms of having greater variety, finer differentiation, and more comprehensive coverage of phenomena, their comments tend to be more profound, more plausible, and more sensible to context (Klein et al. 2007). Experts also tend to show much more anticipatory sense-making and identify actions that must be taken (Rudolph et al. 2009).

From the point of view of the research protocol, in line with the Gioia Methodology, we first conducted six in-depth interviews with the key actors involved in adopting the EQPR in five different public universities. This allowed us to address the topic in depth and identify the first- and second-order concepts to be synthesized into aggregate dimensions. Afterward, to confirm the results obtained from the qualitative interviews and broaden the number of administrative professionals involved in the research, an online survey was sent to all the universities involved in the EQPR project. This was justified by the use of “Triangulation” (Carter et al. 2014; Patton 1999), viewed as a qualitative research strategy to test validity through the convergence of information from different sources and to increase validity and reduce subjectivity in qualitative studies (Jonsen and Jehn 2009). This process was carried on for three reasons: (1) to eliminate or reduce biases and increase the reliability and validity of the study (Jonsen and Jehn 2009); (2) to increase the comprehensiveness of a study (Greene et al. 1989); and (3) to reach increased confidence regarding results that triangulation brings to the researchers (Jick 1979). Therefore, we adopted in-depth interviews as our primary data collection method in the first part of the research. Expert interviews are an effective data collection technique, especially when researchers explore a new, emerging, or under-investigated field (Littig and Pöchhacker 2014). The in-depth interviews were developed, first identifying three levels of analysis: (1) Macro/institutional, (2) Meso/organizational, and (3) Micro/individual. They lasted almost 45 min each, and the timeframe was adequate to properly address and develop the three levels of discussion.

The authors’ team is directly connected with the Italian ENIC/NARIC center (CIMEA). This allows access to experts and scholars representing a significant sample in terms of territorial distribution, size, and organizational complexity of the Italian universities participating in the EQPR project. This first phase of the investigation ended in February 2022.

Our data analysis followed an iterative process of moving back and forth between the collected data, the change management literature, and the sense-making framework. We began by writing a high-level summary of each participant’s response to our questions, which gave us a holistic sense of how individual informants perceived the EQPR process in their organizations. We then performed a more detailed “open coding” analysis of the transcriptions. All authors independently coded the first few transcripts. A considerable number of informant terms, codes, and categories emerged in this process phase, so in looking for similarities and differences, they were synthesized, creating a first-order list of categories that could adhere to the information provided by the interviewees. As suggested by Gioia et al. (2013), the labels were then used to reflect, as knowledgeable agents, on the possible theoretical dimensions and themes that could be connected to the first-order concepts obtained that could be representative of the several dimensions addressed in the literature. Furthermore, following the same line of reasoning, the discourse was pushed further, connecting and aggregating the second-order concepts into aggregate dimensions.

The most significant elements that emerged during the interviews showed an overall impact on the administrative processes related to the EQPR adoption. On these bases, the research’s second phase consisted of an online survey focusing specifically on the administrative units of the entire universe of the Italian universities participating in the EQPR project. The survey aimed to broaden the number of administrative professionals involved in the research and confirm the evidence from the qualitative interviews.

To collect both quantitative and qualitative data, a questionnaire containing 26 Likert scale questions (using a scale of 1 to 7) and 5 open questions was validated by experts. The questionnaire was sent out to all the universities in the CNVQR network (n = 33) between March and April 2022. Nineteen answers were returned, accounting for a 60% response rate. The answers were anonymized, and all the data collected were treated in full compliance with the privacy regulation.

The next phase of data analysis involved all the researchers analyzing and comparing all the information collected and the definitive compilation of all the codes. Cognitive mapping was deployed as a data analysis technique to aid our understanding and evaluation of people’s cognitive complexity in making sense of the EQPR process. This collective analytical effort allowed us to build a data set structured in first-order concept, second-order theme, and aggregate dimensions, capable of highlighting the dynamic relations among the different layers of analysis.

5. Results

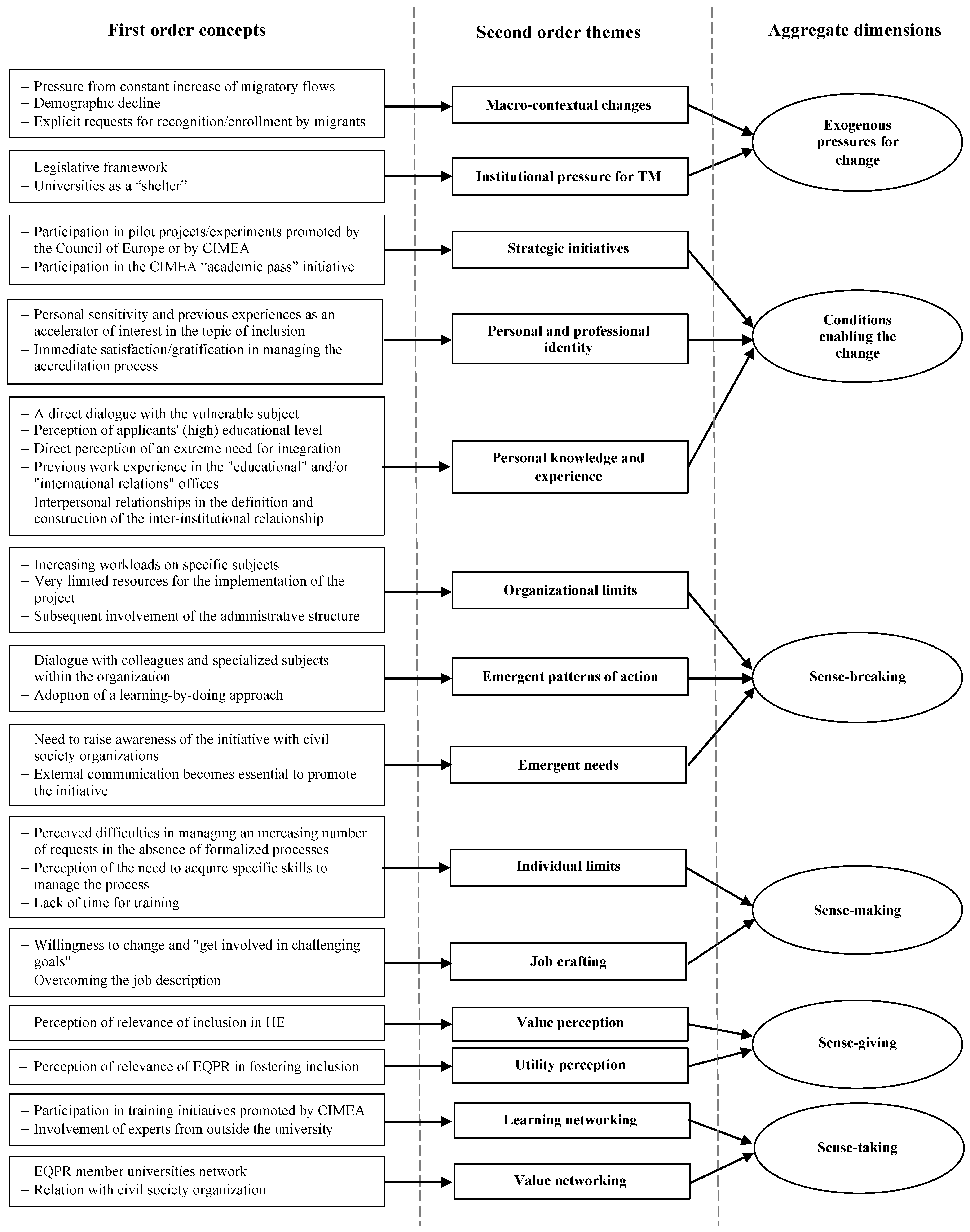

The text and quotes identified during the in-depth interviews were extrapolated and then compared, looking for similarities and differences to be divided into units of meaning successively (first-order concept) (Table 1) that later led to the identification of second-order themes and the following aggregate dimensions (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Quotes identified during the in-depth interviews and related first-order concepts.

Figure 1.

First-order concepts, second-order themes, and aggregate dimensions.

The obtained results show a picture in which some elements are explicit and weigh more than others. Hereinafter we present the main findings of the in-depth interviews.

5.1. Results from the In-Depth Interviews

5.1.1. Exogenous Pressures for Change

Macro-contextual factors, such as the increase in migration flows (e.g., “the sizeable migratory wave of 2015 brought many refugees to Italy”), the demographic decline of the areas where the universities are located (e.g., “The demographic decline is very marked, and every student is essential to us”), and explicit requests for enrolment presented by migrants and refugees (e.g., “it was precisely the request that came from the students”), were indeed essential factors to be considered and found a fertile ground where the sensitivity of those operating towards these issues was more developed. In addition to that, the presence of regulatory precepts, such as Law 148/2011 with the ratification and implementation of the convention on the recognition of qualifications relating to higher education in the European Region (Council of Europe 1997), and strategic choices of the organization towards the internationalization and/or the achievement of the TM (e.g., “there was Law 148 and the ratification of the Lisbon Convention, and from there the process began”), which is recognized as an institutional mission of universities, alongside the traditional teaching and research missions by the Legislative Decree 19/2012 played an essential role in carrying out the processes.

5.1.2. Conditions Enabling the Change

Being involved in the EQPR process was often the result of strategic initiatives that saw the university participating in pilot projects and experimentations promoted by the Council of Europe and by the Italian ENIC-NARIC center (e.g., “the development of the work was mainly in the year 2016–2017 with the CNVQR, then with the Academic Pass to the EQPR”). However, personal sensitivity and previous experiences, unified with gratification for managing the process (e.g., “It is a satisfaction both for the University and for myself”), were the first step at the individual level generally needed to start the process institutionally (e.g., “the initiative was born from my sensitivity to the theme of inclusion, a sensitivity that is absolutely shared by the previous director and also the current one”). This is confirmed by the importance that personal knowledge, such as previous work experiences in educational and international relations offices, can play, and the direct dialogue needed to accompany vulnerable subjects with an extreme need for integration (e.g., “The human relationship exists and is complementary. The technical aspect can help, facilitate and speed up the process, but the human side must always be there”). Additionally, the construction of external networks and inter-institutional relationships to accomplish the program was generally started based on the personal relationships these professionals had with local institutions in which they were volunteering, in some cases.

5.1.3. Sense-Breaking

The will of those operating often has to confront organizational limits such as increasing workloads and limited resources for the project implementation (e.g., “we are still very understaffed”).

Furthermore, to overcome organizational limitations, emergent patterns of actions emerge due to the necessary interlocution with colleagues and specialized subjects (e.g., cultural mediators) that already work within the organization. This process has often led to a “Learning by doing approach” to manage the procedures correctly, solve problems (e.g., the exemption from taxes or the possibility of enrolling in courses while awaiting refugee status), and address emergent needs (e.g., the need to highlight awareness of the initiative, also with external stakeholders) to facilitate the beneficiaries.

5.1.4. Sense-Making

However, beyond the will of individuals to complete the processes, the tasks can unlikely be carried out by a single worker/office or without the involvement of the administrative structure. The limits are not just organizational but also individual (e.g., “I asked the university to attend training courses). The need to acquire new and specific skills to run the program properly for those involved is of great importance (e.g., “unfortunately, the time for training is short, we are overwhelmed by daily activities”). Nonetheless, the operators’ lack of time for training does not have to be underestimated in light of the above-mentioned increased workload and the habit of overcoming their job description (job-crafting).

5.1.5. Sense-Giving

The value perception of the relevance of the process of inclusion in HE (e.g., the idea of being able to help someone) and the utility perception of the EQPR as an instrument of inclusion and integration of the applicants (e.g., “this is a project that effectively allows students to integrate into university and even local life”) are certainly strong motivations that accompanied the operators in their daily work, regardless of the above-mentioned organizational and individual limits to be faced.

5.1.6. Sense-Taking

Great importance has resulted from the participation in training initiatives held by the Italian ENIC-NARIC center (e.g., “I followed all the various courses organized by CIMEA on EQPR certification … the path allows for a continuous exchange of ideas and stimuli”), and the involvement of external experts (e.g., “cultural mediators can promote this initiative) confirms the importance of being involved in a learning network that can foster and add value to these kinds of processes. At the same time, what constitutes value networking is the participation and confrontation with other universities participating in the EQPR network and the relations with Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) that can enrich both the institution and the individuals with information exchanges and dialogue.

5.2. Results from the Survey

As anticipated in the previous paragraph, we tested the model emerging from this qualitative framework, building a survey presented to the entire universe of the Italian universities participating in the EQPR project.

The first significant element highlighted by the analysis of the questionnaires is certainly the confirmation of the model previously described; all the questions proposed have generally collected positive responses. Naturally, the advantage deriving from the use of closed questions with a Likert scale is obtaining a more articulated and comprehensive evaluation of the elements making up the model itself and recognizing which ones are of more significant relative agreement.

Going into more detail, the survey confirmed the concomitance of various exogenous pressures for change at the basis of the adoption of the EQPR, particularly macro-contextual changes such as the pressure on the territories deriving from migratory flows (average value 5.22).

Regarding the factors enabling these processes of change, it cannot be emphasized enough that one of the most relevant elements is undoubtedly the previous personal experience as well as the personal sensitivity of the organizational actors involved, relating to issues such as the social inclusion of migrants (average value 6.13). On the contrary, (relative) low importance is surprisingly attributed to the immediate and recognizable gratification deriving from the work done (average value 4.44).

Indeed, a clear trend emerges in perceiving the university as an institution that has to deal with the inclusion of disadvantaged people (average value 6.61), thus attributing a very significant utility to the EQPR process (average value 6.13) with a positive impact on the reputation of the same university that adopts it (average value 6.30). At the same level of macro analysis, the importance of participation in the university network and the ongoing relationships with civil society organizations is crucial to giving value to the experience (average value 5.13).

Even though the respondents slightly consider the organizational limits, adopting the EQPR does not seem to have unsustainably increased the workloads in the offices (average value 4.48) nor required the activation of specific skills in other offices, such as those of respondents (mean value 4.40). However, adopting the EQPR was a learning-by-doing process (average value 5.04) since no prior procedures were formalized, highlighting personal shortcomings in the skills necessary for carrying out their role in the EQPR process.

Consistently, the personal lack of skills has steadily shown a continuing need for professional training (average value 5.52), which was partially satisfied by the provision of training courses activated in a timely and effective manner (average value 5). Another element of great interest is the willingness of the interviewees to go beyond their job description (average value 5.83), highlighting their desire to go beyond their ordinary job duties (average value 5.78).

6. Discussion

Our study analyzes the change management required by EQPR adoption using the lenses of sense-making and job-crafting to shed light on how individuals enact the change through their job beyond the formal organizational requirements. The emergence of individual decisions and actions, as well as the interactions between the organizational actors and the external stakeholders, create the opportunity for dialogic organizing. In interpreting these dynamics, the reference offered by Sandberg and Tsoukas’s (2015) conceptualization of sense-making constituencies has allowed us to critically reinterpret the elements that emerged and were highlighted by our research. Although the framework used focuses on “organizational activities that are interrupted until they are satisfactorily restored (or in some cases permanently interrupted)” (Sandberg and Tsoukas 2015, p. 36), our research takes a slightly different approach, focusing on emergent activities modeled by a job-crafting process justified by the occurrence of hybrid events (major and minor, planned and unplanned), leaving apart the “disruptive ambiguity” (Weick et al. 2005, p. 413) that is generally considered the rationale for the inception of organizational sense-making. This has led us to a different interpretation of the other foundational dimensions identified, such as the processes of the sense-making efforts and the outcomes, due to the emergence of a job-crafting process that shaped the definition of new activities and the interpretation of the role as previously understood by the organizational actors. The narrative is different when it comes to the factors influencing those processes since the results of our approach confirm the importance of those already mentioned with no need for new interpretations.

To recap what emerges from our research, we are in the presence of hybrid events justified by the specific episode of the EQPR introduction, to which major and minor, planned and unplanned events followed, playing a significant role. Although major events are generally considered, as Sandberg and Tsoukas (2015, p. 36) highlight, “fewer studies have utilized sense-making perspective to study sense-making in episodes triggered by minor planned or unplanned events.” In our case, while major planned events are related to institutional pressure to reach TM goals, major unplanned events are linked to macro-contextual factors, such as pressure from the constant increase of migration flows. Bearing in mind the underestimated importance of minor events, we identified both planned and unplanned minor events. These flows of planned and unplanned events create opportunities for dialogues between internal and external actors, as well as between operations and management. Thus, dialogic change management emerges as a series of processes that lead to dialogic organizational change, especially in the meaningful context of change toward social inclusion. The adoption of the new legislative framework provided by the EQPR introduction and the consequent strategic initiative put in place by the involved institutions, such as the participation in pilot projects and experiments promoted by the Council of Europe or other initiatives by CIMEA, which led to the creation of value networking composed by those universities taking part into the EQPR program and the ongoing relationship and debate with Civil Society Organizations, have been read as a minor planned event. As unplanned minor events, we identified both organizational (i.e., increasing workloads on specific subjects and minimal resources to carry out activities) and individual limits (i.e., perceived difficulty in managing an increasing number of requests in the absence of formalized processes, the perception of the need to acquire specific skills to manage the process, and lack of time for training).

Our results contribute to the understanding of these events as trigger events that increased the necessity to create a new approach to sense-making rooted in a job-crafting process that highlighted the willingness of those actors to assume responsibilities and change and get involved in challenging goals, overcoming the personal job description, leading to the enactment of dialogic change management processes. Other elements that permitted shaping the job-crafting process were justified and enhanced by the dialogue with colleagues and specialized subjects within the organization and adopting a learning-by-doing approach.

In contrast with Sandberg and Tsoukas (2015), outcomes are not interpreted following their schematism since there are no restored (or non-restored) sense and action, but the emergence of a new sense and meaning of the job executed, reached thanks to the individual job-crafting processes. On the contrary, our results confirm that dialogic change management may put forward some situational factors that may influence sense-making processes and outcomes. Regarding the context, demographic decline is strictly linked to the territorial efforts made by universities in light of their TM, where the recognition of the explicit request for enrolment by migrants plays a significant role at the same time, justifying the need to raise awareness of the initiatives carried out with the civil society organizations. The dimension of language emerges in the background of the carried-out interviews, being linked to the narrative of inclusions of vulnerable subjects and being connected simultaneously with several elements related to the identity of the subject involved.

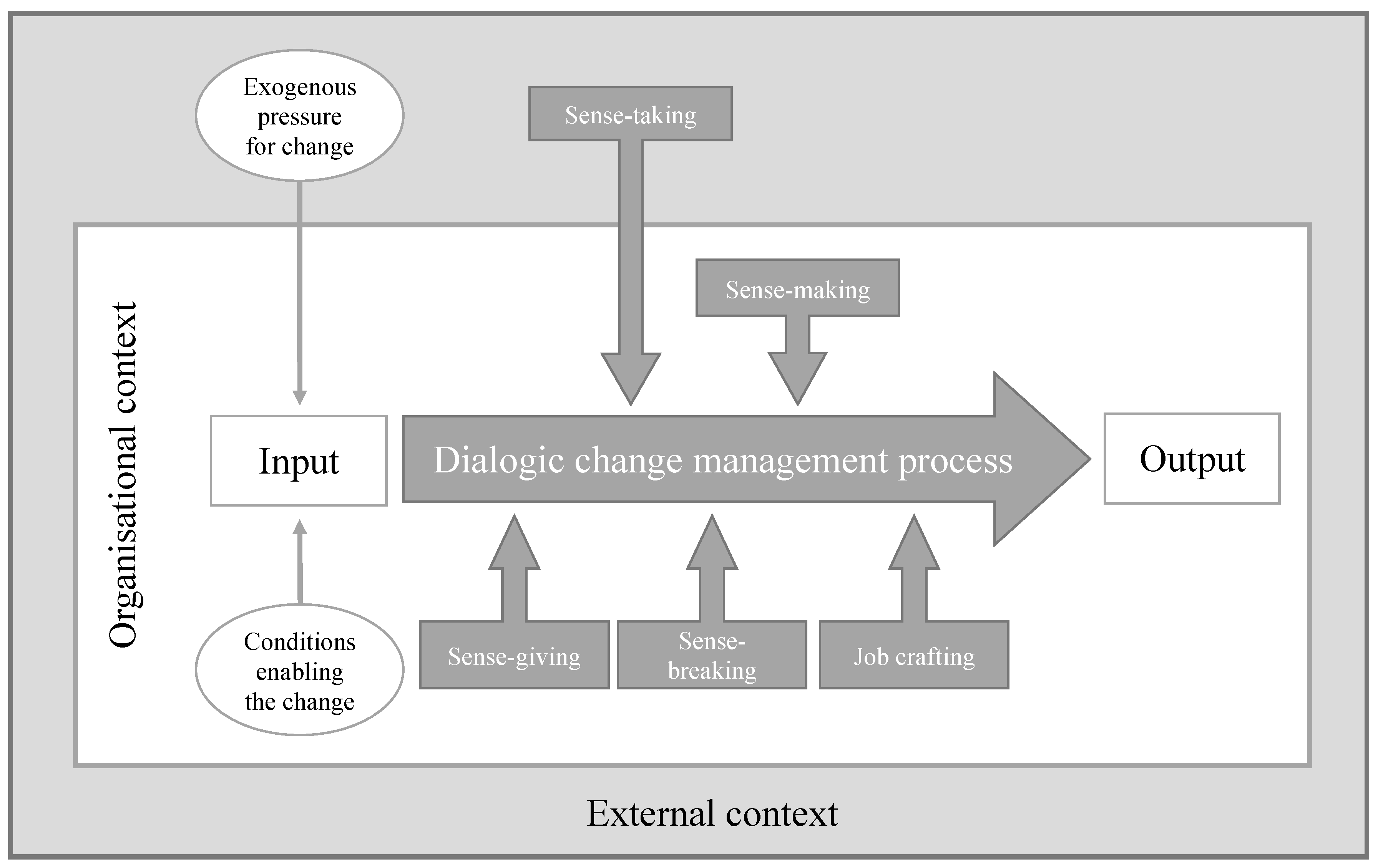

The results of our empirical work allowed for the elaboration of a model based on the two hypotheses proposed by Hastings and Schwarz (2022). Acknowledging a dual nature of the organizational reality, it represents a diagnostic practice (e.g., recognizing contextual macro factors of change, institutional pressure for TM, and subsequent formal adoption of the EQPR protocol), which recognizes reality as objective facts corresponding to organizational states, and a dialogic practice, where reality is socially constructed and expressed through storytelling. In our study, for change to be successful, successful change leaders give both representations an equal voice and must advance jointly. Organizational states must transform, and the narratives that support these new states must be shared. For a schematization of the dialogic change management, please refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The dialogic change management process.

Although looking at how identities influence sense-making has not often been explicitly addressed (Sandberg and Tsoukas 2015), our research shows that elements of identity such as personal sensitivity, knowledge, and previous experiences strongly influence the sense-making processes and the cognitive framework as well (Sheprow and Harrison 2022). The perception of the relevance of inclusion in HEIs and the EQPR as an instrument fostering inclusion emerges from the interviews, leading to the creation of a specific pattern of actions that are developed in the day-by-day activities, contributing to the enrichment of the organization’s (tacit) knowledge.

Contrary to what has always been highlighted in the literature looking at negative emotions’ role in these processes, our results show the importance of positive and bidirectional (i.e., expresser ⇄ perceiver) emotions in sustaining the sense-making process (Yu et al. 2022). Interpersonal relationships, direct and continuous dialogue with vulnerable subjects, the perception of their extreme need for integration, as well as the perceptions of the high educational level of applicants shape the actions carried out by organizational actors.

Technology emerges in the background and plays an essential role as a facilitator of these processes, particularly in communication between public institutions and migrants, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, where procedures were entirely online. Moreover, several developments connected to implementing blockchain technology as a shared database among European institutions have opened the door to new possibilities that have not been fully explored yet.

7. Conclusions

Guided by a sense-making theoretical perspective, our study contributes theoretically to the literature on change management by discussing the processes that enable universities to embrace the challenge of social inclusivity and to give proper space to diverse communities of students. The interplay between sense-taking, sense-breaking, sense-giving, and sense-making (Rom and Eyal 2019) permits the enactment of change in this context, allowing us to both take the specificity of refugee students into full account and give space to the individual interpretation of meanings within the organization towards inclusivity. We suggest that this interplay unlocks the organizational enactment of dialogic change management (Figure 2). From this perspective, our study offers meaningful insights into the role of individuals, their occupational roles, and associated values in pursuing change management toward the organization’s social mission. Furthermore, we contribute to a better understanding of the constituencies of the sense-making processes, supplementing the work by Sandberg and Tsoukas (2015) by elaborating the dialogic change management as a process that is grounded on the constant dialogue between the different dimensions of sense-making, intended as sense-taking, sense-breaking, and sense-giving both at the individual and organizational levels.

Moreover, by focusing on the change process towards the social mission of refugees’ inclusion in the organizational life of universities, we contribute to the literature on HE and HEIs by showing contradictory aspects of the pursuit of the TM concerning the aim of social inclusion. The results from the in-depth interviews show how the “emergent” approach to change seems to better represent, through their dialogic organizational development, the current responses of universities to the demands of their external stakeholders, particularly refugees. The emergent approach sees organizational change as a bottom-up, non-linear, and difficult-to-predict phenomenon, which is therefore non-programmable and dialogic. In the emerging perspective, the change occurs through a continuous interplay of individual events and experiments, often unpredictable and provoked by shifting interests and relationships between different actors and contextual factors.

While the interviewees recall the role of macro and contextual factors as underlying exogenous conditions of change, it is only the role of individuals and their sense-making processes that allow the change to produce organizational change that can lead to positive social impacts. The observed change processes are influenced by a high degree of complexity in terms of environmental factors or components on which the organization depends. This inevitably reduces the possibility that the public organization adopts a “planned” approach to change.

Secondly, the interviews reveal the importance of individual perceptions and experiences as conditions through which the process of organizational change, and its effectiveness and persistence over time, can be enabled. Within this perspective, the individual perceptions and sense-making activities in managing organizational change suggest specific actions useful to create convergent interpretations regarding proper individual courses of action. Furthermore, personal–psychological attitudes and considerations impact change management processes and subjects’ commitment.

Although social goals may not be a central focus of their job, people enact a sense-breaking process to confer new meaning to their job and embed the social mission of inclusion in the organization. Moreover, job-crafting constitutes a way to enact sense-making, by which administrative roles and academics stretch the boundaries of their duties to reach out to marginalized students, help them navigate the academic system, and smooth the EQPR process. Finally, by accessing a network of other mission-driven institutions, individuals may unlock sense-taking opportunities that reinforce the perception of values and social purpose embedded in the organizational change.

8. Practical Implications

The EQPR is a game changer for institutions because it allows, through a rigorous and well-tested methodology, for the assessment of qualifications even in cases when educational documentation is missing. This is a relevant shift in the daily tasks of professionals, as their job involves assessing credentials. Additionally, identifying best practices for implementing the EQPR process will help inform other universities that are not yet part of the process, despite the existing regulatory obligation.

Typically, assessing credentials is research-based work that involves verifying that the core elements of a qualification satisfy the needed requisites and are in line with international and national conventions and legislation concerning the topic. In the case of the EQPR, instead, as documents are missing, HEIs enroll a candidate by accepting a document that verifies the candidate’s declaration, with partial or totally missing supporting documents. It implies a radical change in the perspective of credential evaluators as the research is no longer carried out on paper, but the candidate interviewed is the source of the needed information.

What allowed this change in perspective and, therefore, the use of the EQPR by admission officers, is the trust in the procedure that has been developed together with the confidence in those who have been involved in developing it (the Council of Europe and the ENIC-NARIC centers), but also their participation in the Italian interview sessions. Italian admission officers have been participating in the training provided by the Council of Europe and the more experienced centers, involving the credential evaluators of ENIC-NARIC centers that had to implement it, thus providing the possibility to participate as observers in the interviews and test for themselves the accuracy of the procedure. The present research shows how innovation in the process makes it possible, on the one hand, to overcome a substantial gap, i.e., assess the qualifications of refugees even in case their educational documentation is partially or totally missing, and on the other, how it impacts the whole institution, supporting its capacity to be inclusive and to reinforce its Third Mission effort.

9. Limitations

The number of in-depth interviews and the collected questionnaires gave us a comprehensive view of the process of refugees’ inclusion in the Italian Higher Education system, as we collected evidence from almost all universities participating in the National Coordination for the Evaluation of Refugee Qualifications (CNVQR). Nevertheless, the empirical representation can be considered limited in two aspects. First, unheard voices from the remaining universities should also be included. Second, our survey focused on the voices of administrative staff based on the evidence emerging from the first phase of the empirical analysis.

However, further data collection could complement the present study from the perspective of universities’ top management. Including the perspective of the refugees and other students in the sample could be problematic due to language barriers and potential cultural issues on the one side and the numerosity of the sample on the other. Additionally, we would encourage an international comparison, at least at the European level. Nevertheless, a panel of experts had advised us not to do so, as the national legislators have decided very differently on how to adopt the EQPR, leading to problematic heterogeneity and potential causal ambiguity in the analysis of the cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., P.L. and L.M.; Methodology, F.C., P.L. and L.M.; Investigation, F.C. and P.L.; Data curation, F.C. and P.L.; Writing—original draft, F.C. and P.L.; Writing—review & editing, F.C., P.L. and L.M.; Supervision, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abreu, Maria, Pelin Demirel, Vadim Grinevich, and Mine Karataş-Özkan. 2016. Entrepreneurial practices in research-intensive and teaching-led universities. Small Business Economics 47: 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, Aliyyah, Camille Le Coz, and Hanne Beirens. 2020. Using Evidence to Improve Refugee Resettlement: A Monitoring and Evaluation Road Map. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haddad, Serina, and Timothy Kotnour. 2015. Integrating the organizational change literature: A model for successful change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 28: 234–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Ben, and Jill Fenton. 2008. Spaces of hope. Space and Culture 11: 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenakis, Achilles A., and Stanley G. Harris. 2009. Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management 9: 127–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aula, Pekka, and Saku Mantere. 2013. Making and breaking sense: An inquiry into the reputation change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 26: 340–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartunek, Jean M. 1984. Changing interpretive schemes and organizational restructuring: The example of a religious order. Administrative Science Quarterly 29: 355–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushe, Gervase R., and Robert J. Marshak. 2009. Revisioning organization development: Diagnostic and dialogic premises and patterns of practice. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 45: 348–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushe, Gervase R., and Robert J. Marshak. 2015. Introduction to the dialogic organization development mindset. In Dialogic Organization Development: The Theory and Practice of Transformational Change. Edited by Gervase R. Bushe and Robert J. Marshak. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publichers, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Nancy, Denise Bryant-Lukosius, Alba DiCenso, Jennifer Blythe, and Alan J. Neville. 2014. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum 41: 545–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagnucci, Lorenzo, and Francesca Spigarelli. 2020. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 161: 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe (CoE). 1997. Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications Concerning Higher Education in the European Region. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007f2c7 (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Luc M. Soyer, Maria Vakola, and Despoina Xanthopoulou. 2021. The effects of a job crafting intervention on the success of an organizational change effort in a blue-collar work environment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 94: 374–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, Peter D., and Adrianna J. Kezar. 2003. Taking the Reins: Institutional Transformation in Higher Education. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). 2018. Common European Asylum System. Available online: https://euaa.europa.eu/asylum-report-2020/21-common-european-asylum-system-and-current-issues (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- European Commission. 2023. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/promoting-our-european-way-life/statistics-migration-europe_en#seeking-asylum-in-europe (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Eurostat. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Fernandez, Sergio, and Hal G. Rainey. 2006. Managing successful organizational change in the public sector. Public Administration Review 66: 168–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchietti, Chiara, and Sjur Bergan. 2021. Opening Up Education Opportunities for Refugee Scholars. University World News. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210322124447931 (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Fiss, Peer C., and Edward J. Zajac. 2006. The symbolic management of strategic change: Sensegiving via framing and decoupling. Academy of Management Journal 49: 1173–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Jeffrey, Laurie Ford, and Beth Polin. 2021. Leadership in the implementation of change: Functions, sources, and requisite variety. Journal of Change Management 21: 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Dennis A., and James B. Thomas. 1996. Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Administrative Science Quarterly 41: 370–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Dennis A., and Kumar Chittipeddi. 1991. Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal 12: 433–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2013. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods 16: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, Laura, and Linda Duxbury. 2018. Making sense of organizational change: Is hindsight really 20/20? Journal of Organizational Behavior 39: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Jennifer C., Valerie J. Caracelli, and Wendy F. Graham. 1989. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11: 255–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, Maribel, and David Urbano. 2010. The development of an entrepreneurial university. Journal of Technology Transfer 37: 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Bradley J., and Gavin M. Schwarz. 2022. Leading change processes for success: A dynamic application of diagnostic and dialogic organization development. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 58: 120–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, Daniel, and Chris Steyaert. 2021. Stirring and Disturb—Urging the Movement of Academic Entrepreneurship Onwards. In New Movements in Academic Entrepreneurship. Edited by Paivi Eriksson, Ulla Hytti, Katri Komulainen, Tero Montonen and Paivi Siivonen. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 254–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huemer, Lars. 2012. Organizational identities in networks: Sense-giving and sense-taking in the salmon farming industry. The IMP Journal 6: 240–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jabri, Muayyad. 2017. Managing Organizational Change: Process, Social Construction and Dialogue. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Gabriele, Arjen Van Witteloostuijn, and Jochen Christe-Zeyse. 2013. A theoretical framework of organizational change. Journal of Organizational Change Management 26: 772–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Angelika, and Johannes Kopper. 2014. Third mission potential in higher education: Measuring the regional focus of different types of HEIs. Review of Regional Research 34: 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, Maddy, and Patrizia Zanoni. 2021. Making diversity research matter for social change: New conversations beyond the firm. Organization Theory 2: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrel, Teo. 2017. Success Factors for Implementing Change at Scale. New York: McKinsey & Co Presentation, Behavioral Science & Policy Association. [Google Scholar]

- Jick, Tood D. 1979. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 602–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsen, Karsten, and Karen A. Jehn. 2009. Using triangulation to validate themes in qualitative studies. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 4: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Gary, Jennifer K. Phillips, Erica L. Rall, and Deborah A. Peluso. 2007. A data–frame theory of sensemaking. In Expertise Out of Context. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 118–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers, Ben S., Malcolm Higgs, Walter Kickert, Lars Tummers, Jolien Grandia, and Joris Van Der Voet. 2014. The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Administration 92: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Paul. 2015. Leading change–Insights into how leaders actually approach the challenge of complexity. Journal of Change Management 15: 231–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, Beate, and Franz Pöchhacker. 2014. Socio-translational collaboration in qualitative inquiry: The case of expert interviews. Qualitative Inquiry 20: 1085–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, Michela, and Maria Chiara Di Guardo. 2015. The third mission of universities: An investigation of the espoused values. Science and Public Policy 42: 855–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, Sally, and Thomas B. Lawrence. 2007. Triggers and enablers of sensegiving in organizations. Academy of Management Journal 50: 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, Giovanna, Ada Carlesi, and Alfredo Scarfò. 2018. Academic spin offs as a value driver for intellectual capital. The case of the University of Pisa. Journal Intellectual Capital 19: 202–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, John W., and Baird K. Brightman. 2001. Leading organizational change. Career Development International 6: 111–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, Sinead, and Sayers Eric. 1996. Organizational change through individual learning. Career Development International 1: 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, Greg R., and Yitzhak Fried. 2016. Job design research and theory: Past, present and future. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 136: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, Shaul, and Yair Berson. 2019. Leaders’ impact on organizational change: Bridging theoretical and methodological chasms. Academy of Management Annals 13: 272–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, Shaul, Maria Vakola, and Achilles Armenakis. 2011. Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 47: 461–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1999. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research 34: 1189. [Google Scholar]

- Petrou, Paraskevas, Evangelia Demerouti, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2018. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. Journal of Management 44: 1766–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Dave. 2000. Making sense of the total of two dice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 31: 602–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, Steward, Bob Hinings, and Royston Greenwood. 1980. The structuring of organizational structures. Administrative Science Quarterly 25: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasi, Davide, and Maiken Schultz. 2006. Responding to organizational identity threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal 49: 433–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, Noa, and Ori Eyal. 2019. Sensemaking, sense-breaking, sense-giving, and sense-taking: How educators construct meaning in complex policy environments. Teaching and Teacher Education 78: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, Jenny W., J. Bradley Morrison, and John S. Carroll. 2009. The dynamics of action-oriented problem solving: Linking interpretation and choice. Academy of Management Review 34: 733–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, Jorgen, and Haridimos Tsoukas. 2015. Making sense of the sensemaking perspective: Its constituents, limitations, and opportunities for further development. Journal of Organizational Behavior 36: 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheprow, Elizabeth, and Spencer H. Harrison. 2022. When regular meets remarkable: Awe as a link between routine work and meaningful self-narratives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 170: 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerek, Ryan. 2011. Sensemaking and sensegiving: An exploratory study of the simultaneous “being and learning” of new college and university presidents. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 18: 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, Amy. 2020. Supporting Young Refugees in Transition to Adulthood through Youth Work and Youth Policy. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Stouten, Jeroen, Denise M. Rousseau, and David De Cremer. 2018. Successful organizational change: Integrating the management practice and scholarly literatures. Academy of Management Annals 12: 752–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, F. Ian. 1998. The influence of organizational culture and internal politics on new service design and introduction. International Journal of Service Industry Management 9: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2015. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2015. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Urdari, Claudia, Tteodora Vica Farcas, and Adriana Tiron-Tudor. 2017. Assessing the legitimacy of HEIs’ contributions to society: The perspective of international rankings. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 8: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, Jaakko. 2009. Two theories of organizational knowledge creation. In Learning and Expanding with Activity Theory. Edited by Annalisa Sannino, Harry Daniels and Kris D. Gutiérrez. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 144–59. [Google Scholar]

- Vorley, Tim, and Jen Nelles. 2008. (Re) conceptualising the academy: Institutional development of and beyond the third mission. Higher Education Management and Policy 20: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. New York: Sage, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl E., and Robert E. Quinn. 1999. Organizational change and development. Annual Review of Psychology 50: 361–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, Karl E., Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld. 2005. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science 16: 409–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, and Jane E. Dutton. 2001. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review 26: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, Amy, Jane E. Dutton, and Gelaye Debebe. 2003. Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behavior 25: 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Xiaodan, Yuanyanhang Shen, and Deepak Khazanchi. 2022. Swift trust and sensemaking in fast response virtual teams. Journal of Computer Information Systems 62: 1072–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, Gary. 2012. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).