The Maturity of Strategic Networks’ Governance: Proposal of an Analysis Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Characteristics of SNs

2.2. Corporative Governance

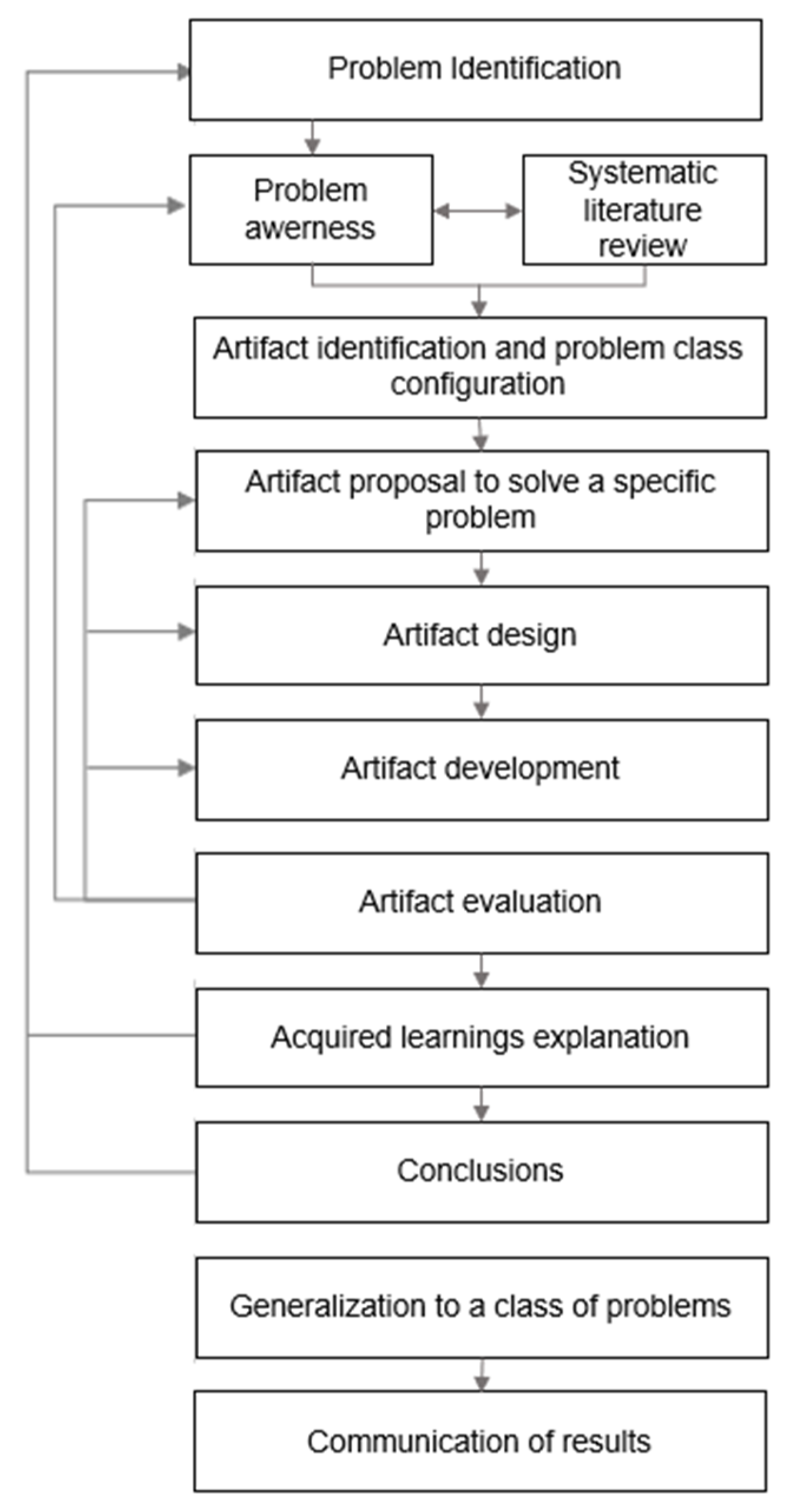

3. Method

4. Artifact Development

4.1. Governance Maturity Levels

4.2. Testing the Model and Data Generated in the Testing Stage

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Contributions

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Full Version of the Proposed Artifact

| Fundamental Pillars of Governance and Themes (ESG) | Final Artifact | Based on |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | (1) Despite the need for SN management transparency, managers recognize the importance of data protection and privacy and implement procedures to comply with the General Personal Data Protection Law (LGPD), Law No. 13,709. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); Return of the experts (2021). |

| (2) SN Management—Formal disclosure of information related to SN management processes, rules, responsibilities, and attributions. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010) | |

| (3) SN Management—The members are aware of the requirements, criteria, and skills for selecting SN management members, which are decisive. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010) | |

| (4) Conflict resolution—SN members are constantly updated on any conflicts of interest arising in the SN and how these conflicts were resolved. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010) | |

| (5) SN Management—Membership—As part of pre-contractual clarification, SN management contributes to information transparency and entry and exit conditions for potential SN members. It allows potential SN participants to gain insight into the SN’s economic situation. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010) | |

| (6) SN Management—Information transparency from the SN to external stakeholders—SN management provides information to various external stakeholders relevant to their cooperation with the SN. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| Equity | (1) SN Management—Assembly and dialogue with members on the SN’s situation and development—The SN’s general meeting provides an open dialogue about the SN’s situation and development between members and the SN administration. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) |

| (2) SN Management—Elections of members of the Board of Directors and Fiscal Council—Members are aware of and have access to information about the criteria and requirements for participating in elections as members of the Board of Directors and Fiscal Council, allowing it to ensure equal rights to all members under the same conditions. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (3) SN Management—Communication that allows for dialogue and alignment of activities with members’ interests—There is an open channel of communication that allows for dialogue between SN management and members to align SN activities with members’ interests. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (4) SN Management—Compliance with the SN Bylaws and Regulations by its managers and members—They adhere to the SN Bylaws and Regulations. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (5) SN Management—SN Committees: Other committees are formed to meet the mutual needs of participation and information, such as working groups or experience exchange groups, in addition to the control committees (board of directors, supervisory board) and advisory committees (advisory board that advises management). | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (6) SN Management—Member entry and exit conditions | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| Accountability | (1) Trust and responsibility—The SNs’ management presents and provides transparency of the records of its acts performed to the board of directors and supervisory board, or, in their absence, to the members, as these actions are necessary to create the necessary environment of mutual trust, while always adhering to the duty of confidentiality regarding information. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) |

| (2) Risk management and information transparency—SN management acts with diligence (commitment) and accountability. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (3) Risk Management—Risk assessment and management. A Risk Committee or Responsible Group meets regularly to analyze and manage risks, allowing the SN to monitor its effectiveness. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (4) SN Management—Accountability of the Fiscal Council and Board of Directors—A fiscal council and board of directors accounts for its management acts and the exercise of its attributions regularly. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (5) SN Management—Internal audit—The Fiscal Council performs the internal audit, and council members have the technical conditions for this attribution and sharing reports generated with SN management. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (6) SN Management—External Audit—An independent external audit is hired, and the general meeting determines the audit’s remuneration. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| Corporate Responsibility | (1) SN planning and sustainability—SN management promotes value-aligned management and long-term strategic vision by reflecting on the cycles of growth, maturity, and reorientation of its activities. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) |

| (2) More collaborative and future-oriented SN leadership—Decision-Making Process—The SN management decision-making process is formalized and organized so that the SN can block decisions that meet individual interests but not common interests. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (3) SN Planning and Longevity—Strategic plan development—SN management develops a strategic plan, which is discussed with the fiscal council and board of directors, establishing guidelines and strategic objectives. These objectives are monitored and disclosed, and, if necessary, action plans to improve results are prepared. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (4) SN succession planning—The cooperation SN has succession planning in place for the board of directors and the presidency, which includes the identification of potential successors as well as the management transfer process. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (5) SN Succession Planning—Creating a plan to deal with the departure of Board and Chair members. | Deutscher Franchiseverband (2010); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (6) Conflict resolution—In businesses, conflicts of interest are resolved through hierarchical structures, whereas in SNs, conflicts are resolved through participatory processes. Internal conflict resolution procedures may be outlined in the SN’s Bylaws. | GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) matters | (1) Opportunities related to the ESG theme—The SN considers the objectives and actions to be carried out concerning environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) themes in its strategic planning. | CVM (2021) |

| (2) The SN creates a report or document that contains information about environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) topics. | CVM (2021) | |

| (3) Disclosure—The SN discloses social, environmental, and corporate governance (ESG) information in an annual report or another specific document for this purpose and indicates where this document or information can be found on the institutional website. | CVM (2021) | |

| (4) Environmental practices—SN members use renewable energy (e.g., solar panels). | CVM (2021) | |

| (5) Environmental practices—The SN has a code of conduct or policy for working with suppliers (who use organic inputs or even those with environmental certifications). | CVM (2021) | |

| (6) Environmental Practices—The chain has a policy of conduct or negotiation with suppliers who provide reverse logistics of products (e.g., collection of used light bulbs, batteries, and packaging). | CVM (2021) | |

| (7) Social—Does the SN have a mission statement and strategic guidelines? If this is the case, it should accurately represent the SN’s performance and explicitly seeks to benefit society. | CVM (2021) | |

| (8) Social—Training and Development (T&D) for SN directors and employees—The cooperation SN invests in training and development for its directors, president, and employees. | CVM (2021); GT Interagentes (2016) | |

| (9) Social—Diversity—The SN has a specific policy or goals for gender, color, or racial diversity among its management bodies (board of directors, the presidency, and members of the management and supervisory boards). | CVM (2021) | |

| (10) Governance—The SN has established communication channels through which critical issues in ESG matters and practices can be brought to the attention of the presidency or the board of directors, as applicable. | CVM (2021) |

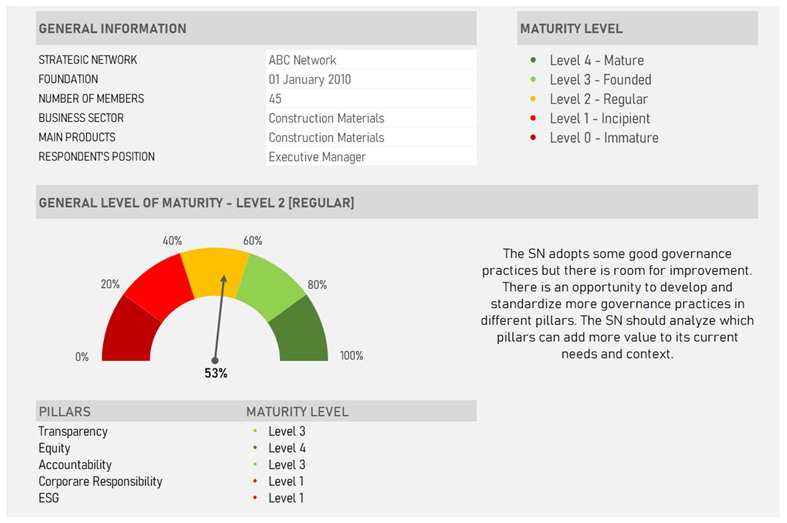

Appendix B. Example of Artifact’s Outcome

| 1 | According to the European Commission (2023), medium-sized firms are defined as those with up to 250 employees or up to GBP 50 million in annual revenue. In emerging countries such as Brazil, medium-sized firms are defined as those with up to 99 employees (commerce) or 499 employees (industry)—(BNDES 2023). |

References

- Abu-Tapanjeh, Abdussalam Mahmoud. 2009. Corporate governance from the Islamic perspective: A comparative analysis with OECD principles. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 20: 556–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George A. 1970. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In Uncertainty in Economics. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 235–51. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Carlos Alberto Tavares de. 2011. Fundos de pensão e governança corporativa no Brasil. Master’s thesis, FGV, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Available online: http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/8483 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Anceco. 2023. Las CCS en España. Available online: https://anceco.com/actualidad-ccs/las-ccs-en-espana/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1978. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. In Uncertainty in Economics. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 345–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bilyay-Erdogan, Seda. 2022. Corporate ESG engagement and information asymmetry: The moderating role of country-level institutional differences. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNDES BANCO NACIONAL DE DESENVOLVIMENTO. 2023. Porte de empresa. Available online: https://www.bndes.gov.br/wps/portal/site/home/financiamento/guia/porte-de-empresa (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Bosáková, Ivana, Aleš Kubíček, and Jiří Strouhal. 2019. Governance Codes in the developing and emerging countries: Do they look for the international role model? Economics and Sociology 12: 251–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, Kateryna, and Ivan Derun. 2016. Disclosure of non-financial information in corporate social reporting as a strategy for improving management effectiveness. Journal of International Studies 9: 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Susanne. 2012. Network Governance Kodex: Steigerung der Wettbewerbsfähigkeit von Unternehmen (snetzwerken) durch Selbstverpflichtung. ZfKE–Zeitschrift für KMU und Entrepreneurship 60: 239–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buertey, Samuel, Eun-Jung Sun, Jang Soon Lee, and Juhee Hwang. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and earnings management: The moderating effect of corporate governance mechanisms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 256–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadbury, Adrian. 1992. Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. Gee, London. Available online: https://ecgi.global/code/cadbury-report-financial-aspects-corporate-governance (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Carioca, Karla Jeanny Falcão, Márcia Martins Mendes De Luca, and Vera Maria Rodrigues Ponte. 2010. Implementação da Lei Sarbanes-Oxley e seus impactos nos controles internos e nas práticas de governança corporativa: Um estudo na companhia energética do Ceará-Coelce. Revista Universo Contábil 6: 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Yan-Leung, Ping Jiang, and Weiqiang Tan. 2010. A transparency disclosure index measuring disclosures: Chinese listed companies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 29: 259–80. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão de Valores Mobiliários—CVM. 2002. Recomendações da CVM sobre governança corporativa. Comissão de Valores Mobiliário. Available online: http://conteudo.cvm.gov.br/export/sites/cvm/decisoes/anexos/0001/3935.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Comissão de Valores Mobiliários—CVM. 2019a. Instrução CVM nº 480, de 07 de dezembro de 2009. Dispõe sobre o registro de emissores de valores mobiliários admitidos à negociação em mercados regulamentados de valores mobiliários. Available online: https://conteudo.cvm.gov.br/legislacao/instrucoes/inst480.html (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Comissão de Valores Mobiliários—CVM. 2019b. Mercado de valores mobiliários brasileiro, 4th ed. Comissão de Valores Mobiliário: Available online: https://www.investidor.gov.br/portaldoinvestidor/export/sites/portaldoinvestidor/publicacao/Livro/livro_TOP_mercado_de_valores_mobiliarios_brasileiro_4ed.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Comissão de Valores Mobiliários—CVM. 2021. Resolução CVM nº 59, de 22 de dezembro de 2021. Altera a Instrução CVM nº 480, de 7 de dezembro de 2009, e a Instrução CVM nº 481, de 17 de dezembro de 2009. Available online: https://conteudo.cvm.gov.br/legislacao/resolucoes/resol059.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Crisóstomo, Vicente Lima, Victor Daniel Vasconcelos, and Célia Maria Braga Carneiro. 2021. Análise da relação entre responsabilidade social corporativa e governança corporativa na empresa brasileira. Perspectivas Contemporâneas 16: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, Caroline Cordova Bicudo, Aruana Rosa Souza Luz, and Douglas Wegner. 2022. Are there differences between governing and managing strategic networks of different sizes and ages? Journal of Management & Organization. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Qi, and Shaobo Ji. 2018. A review of design science research in information systems: Concept, process, outcome, and evaluation. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems 10: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Franchiseverband. 2010. Network-governance-kodex: Exzellente unternehmensführung in kooperativen unternehmensnetzwerken. Available online: www.mittelstandsverbund.de/media/f3b71225-6af7-430d-b966-03cd724e41d0/0Q7mYg/Import/network-governance-kodex_druckversion.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Dresch, Aline, Daniel Pacheco Lacerda, and José Antonio Valle Antunes Junior. 2015. Design science research: Método de pesquisa para avanço da ciência e tecnologia. Porto Alegre: Bookman Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, Ellen, Rachel M. Hayes, and Xue Wang. 2007. The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and firms’ going-private decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 44: 116–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2023. SME Definition. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/smes/sme-definition_en (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Gregory, Alan, Rajesh Tharyan, and Julie Whittaker. 2014. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Disaggregating the effects on cash flow, risk, and growth. Journal of Business Ethics 124: 633–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GT Interagentes. 2016. Código Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa: Companhias Abertas. Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa. Available online: https://www.anbima.com.br/data/files/F8/D2/98/00/02D885104D66888568A80AC2/Codigo-Brasileiro-de-Governanca-Corporativa_1_.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Gulati, Ranjay. 1998. Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal 19: 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa. 2014. Caderno de boas práticas de governança corporativa para empresas de capital fechado: Um guia para sociedades limitadas e sociedades por ações fechadas. São Paulo. Available online: http://www.ibgc.org.br/userfiles/files/2014/files/Arquivos_Site/Caderno_12.PDF (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Jarillo, J. Carlos. 1993. Strategic Networks: Creating the Borderless Organization. Oxford: Butterwoth-Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Leander Luiz, Nelson Beuter Júnior, and Kadígia Faccin. 2022. Innovation in networks of companies with different governance structures. International Journal of Business Excellence 27: 125–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoepfel, Ivo. 2004. Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World. UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://d306pr3pise (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny. 2002. Investor protection and corporate valuation. The Journal of Finance 57: 1147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, Somnath, Sumit Kundu, and Surender Munjal. 2021. Processes underlying interfirm cooperation. British Journal of Management 32: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Luciana de Souza. 2013. Governança Corporativa, Valor e Desempenho de Empresas com Participação Acionária de Fundos de Pensão no Brasil. Doctoral dissertation, PUC-RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, Luciana de Souza, Luiz Felipe Jacques da Motta, André Luiz Carvalhal da Silva, and Vinícius Mothé Maia. 2017. Governança corporativa, valor e desempenho de empresas com participação acionária de fundos de pensão. Gestão Contemporânea 19: 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Macagnan, Clea Beatriz. 2009. Voluntary disclosure of intangible resources and stock profitability. Intangible Capital 5: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstandsverbund. 2023. Stark für den Mittelstand. Available online: https://www.mittelstandsverbund.de/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Monticelli, Jefferson Marlon, and Douglas Wegner. 2022. Institutional change and stability in strategic networks in the Brazilian pharmaceutical industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing 16: 260–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Elisabeth F. 2021. Towards a theory of network facilitation: A micro-foundations perspective on the antecedents, practices, and outcomes of network facilitation. British Journal of Management 32: 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2004. The OECD principles of corporate governance. Contaduría y Administración 216: 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Amalya L., and Mark Ebers. 1998. Networking network studies: An analysis of conceptual configurations in the study of inter-organizational relationships. Organization Studies 19: 549–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahi, Debasis, and Inder Sekhar Yadav. 2019. Does corporate governance affect dividend policy in India? Firm-level evidence from new indices. Managerial Finance 45: 1219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, Jukka, Olli-Pekka Kauppila, Fabian Sepulveda, and Mika Gabrielsson. 2020. Turning strategic network resources into performance: The mediating role of network identity of small-and medium-sized enterprises. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14: 178–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, Patrizia, Antonio Ricciardi, and Silvia Tommaso. 2020. Contractual networks: An organizational model to reduce the competitive disadvantage of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Europe’s less developed regions. A survey in southern Italy. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 16: 1503–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, Rekha, and Husam-Aldin Nizar Al-Malkawi. 2018. On the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from GCC countries. Research in International Business and Finance 44: 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanath, H. M. S., and Awanthi Buthsala. 2017. Information, opportunism and business performance: A case of small businesses managed by women entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka. Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies 5: 230–39. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, Keith G., and Patrick Kenis. 2008. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punsuvo, Fábio Riberi. 2006. Qualidade da Governança Corporativa e a participação societária dos Fundos de Pensão nas empresas de capital aberto brasileiras. Master’s thesis, Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Lema, Ximena, Victor Pumisacho, Juan-José Alfaro-Saiz, and Daniela García. 2019. Evaluating management practices in horizontal cooperation SMEs networks: The Ecuadorian context. Gestão & Produção 26: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. A Survey of Corporate Governance. Journal of Finance 52: 737–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, Samya, Sadaf Ehsan, Mohammad Kabir Hassan, and Qamar Uz Zaman. 2021. Does corporate governance compliance condition information asymmetries? Moderating role of voluntary disclosures. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies 30: 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoore, Jorge Renato, Douglas Wegner, and Alsones Balestrin. 2015. The evolution of collaborative practices in small-firm networks: A qualitative analysis of four Brazilian cases. International Journal of Management Practice 8: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Huanming, and Bing Ran. 2022. Network governance and collaborative Governance: A thematic analysis on their similarities, differences, and entanglements. Public Management Review. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Douglas. 2019. Redes, alianças e parcerias: Ferramentas para a gestão da cooperação empresarial. Porto Alegre: EST. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Douglas, and Jorge Renato Verschoore. 2022. Network governance in action: Functions and practices to foster collaborative environments. Administration & Society 54: 479–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Douglas, Felipe de Mattos Zarpelon, Jorge Renato Verschoore, and Alsones Balestrin. 2017. Management practices of small-firm networks and the performance of member firms. Business: Theory and Practice 18: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Douglas, Greici Sarturi, and Leander Luiz Klein. 2022a. The governance of strategic networks: How do different configurations influence the performance of member firms? Journal of Management and Governance 26: 1063–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Douglas, Ingridi Vargas Bortolaso, and Patrinês Aparecida França Zonatto. 2016. Small-Firm Networks and Strategies for Consolidation: Evidence from the Brazilian context. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios 18: 525–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, Douglas, Marcelo Fernandes Pacheco Dias, Ana Cláudia Azevedo, and Diego Antonio Bittencourt Marconatto. 2022b. Configuring the governance and management of strategic networks for higher performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 37: 2501–14. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Oliver Eaton. 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2020. Embracing the New Age of Materiality: Harnessing the Pace of Change in ESG. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

| Principle | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | Establishes that the corporate governance structure must ensure the disclosure of relevant information regarding the financial situation and performance to all interested parties, not just those mandated by laws or regulations. | Abu-Tapanjeh (2009); Bosáková et al. (2019); Cadbury (1992); Cheung et al. (2010); GT Interagentes (2016); OECD (2004). |

| Equity | All partners/shareholders and other stakeholders must be treated fairly and equally by the corporate governance structure, with their rights, duties, needs, interests, and expectations safeguarded. In addition, the organization should ensure that its partners and shareholders have the right to participate in and influence the decisions made by the organization. | Abu-Tapanjeh (2009); Bosáková et al. (2019); Cadbury (1992); GT Interagentes (2016); OECD (2004). |

| Accountability | Governance agents, represented by partners, administrators, fiscal councilors, and auditors, must account for their actions and accept full responsibility for any consequences resulting from their actions and omissions. They should act with diligence and responsibility within the scope of their roles. | Abu-Tapanjeh (2009); Bosáková et al. (2019); Cadbury (1992); GT Interagentes (2016); OECD (2004). |

| Corporate Responsibility | Governance agents must ensure the organization’s economic and financial viability and sustainability while also reducing negative externalities and increasing positive ones. They should also consider the positive impacts of the organization’s activities, products, and services in the short, medium, and long term. | Abu-Tapanjeh (2009); Bosáková et al. (2019); Cadbury (1992); GT Interagentes (2016); OECD (2004). |

| SN ¹ | Existence Time | Operation Region | Number of Associated Firms | Code ¹ | Manager Role | Manager Participation Time in the SN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 22 years | São Paulo—Brazil | 18 member firms and 33 stores | G01 | SN Manager | 4 years |

| B | 22 years | Rio Grande do Sul—Brazil | 78 member firms and 108 stores | G02 | CEO | 6 years |

| C | 20 years | 9 Brazilian states | 16 member firms and 17 stores | G03 | SN Manager | 10 years |

| Scale Performance | Score |

|---|---|

| Fully complies | 3 |

| Complies | 2 |

| Partially complies | 1 |

| Does not comply | 0 |

| Level | Percentage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Level 4 Mature | >80% to 100% | Congratulations, the SN structured its governance system and adopted good governance practices. These practices are based on the fundamental governance pillars and are applied within the context of SNs. Governance contributes to aligning the interests of all parties involved and promotes transparency in activities, with the ultimate goal of preserving the long-term value of the network. |

| Level 3 Founded | >60% to 80% | The SN adopts good governance practices in a relatively structured manner. There is an opportunity to consolidate and improve the use of good practices while considering the SN’s context. Please note the specific dimensions that require further improvement. |

| Level 2 Regular | >40% to 60% | The SN adopts some good governance practices, but there is room for improvement. There is an opportunity to develop and standardize governance practices across various pillars. The SN should analyze which pillars can provide the most value in the current context and for its current needs. |

| Level 1 Incipient | >20% to 40% | The SN has incipient levels of good governance practices. There is an opportunity to formalize and institutionalize the adoption of good governance practices, and it is essential to consider the SN’s current context. The institutionalization of governance practices in the SN may provide greater transparency to members, restrict managers’ autonomy, and professionalize management. |

| Level 0 Immature | 0% to 20% | The SN does not adopt good governance practices. The SN should begin to reflect on the importance of governance practices, considering the SN structure and characteristics. Governance helps to ensure transparency, protect members’ interests, and preserve the SN’s long-term value. The pillars considered are the foundation for governance practices and can be implemented by any organization, regardless of its size, legal structure, or type of control. |

| Basic Pillars + ESG | Number of Items | Maximum Score Possible | Score Obtained in the Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency | 6 | 18 | 12 |

| Equity | 6 | 18 | 18 |

| Accountability | 6 | 18 | 12 |

| Corporate Responsibility | 6 | 18 | 18 |

| ESG | 10 | 30 | 12 |

| Total | 34 | 102 points | 72 points |

| 100% | 71% |

| Basic Pillars + ESG | Number of Items | Maximum Possible Score | Score Strategic Network A | Score Strategic Network B | Score Strategic Network C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency | 6 | 18 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| Equity | 6 | 18 | 15 | 13 | 11 |

| Accountability | 6 | 18 | 12 | 10 | 8 |

| Corporate Responsibility | 6 | 18 | 12 | 12 | 9 |

| ESG | 10 | 30 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| Total | 34 | 102 | 59 | 53 | 41 |

| Percentage | 100% | 58% | 52% | 40% | |

| Maturity level | Level 2 Regular | Level 2—Regular | Level 1—Incipient |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winkler, M.; Wegner, D.; Macagnan, C.B. The Maturity of Strategic Networks’ Governance: Proposal of an Analysis Model. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050134

Winkler M, Wegner D, Macagnan CB. The Maturity of Strategic Networks’ Governance: Proposal of an Analysis Model. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(5):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050134

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinkler, Marione, Douglas Wegner, and Clea Beatriz Macagnan. 2023. "The Maturity of Strategic Networks’ Governance: Proposal of an Analysis Model" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 5: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050134

APA StyleWinkler, M., Wegner, D., & Macagnan, C. B. (2023). The Maturity of Strategic Networks’ Governance: Proposal of an Analysis Model. Administrative Sciences, 13(5), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13050134