Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to develop a better understanding of how to define a positive climate for inclusiveness that recognizes the context and social environment of participants. In order to study employees working with Indigenous people and minorities in four organizations, we used a grounded research approach to define what an inclusive environment might look like. The interview questions gathered examples of experiences which employees valued because they felt more included and not excluded from people they worked with. The experiences fell into four categories, as follows: (i) leadership engaged in supporting inclusiveness within the organization; (ii) leadership engaged in seeking inclusiveness within the community; (iii) being involved in multicultural practices within the organization and community; and (iv) participating in initiatives which encourage engagement and involvement. This paper’s conceptualization of a climate of inclusion is different from other studies, possibly because of the unique context in which service organizations are placed, as such organizations typically work with Indigenous people and minorities. Although we are especially mindful of the danger of generalizing our findings without further research, the scope of this paper might provide some direction for future studies of other organizations. We suggest that there is also a need to be open to methods which allow individuals and groups to define a climate of inclusivity that is relevant to their context; this is because context may be essential for recognizing certain groups of people.

1. Introduction

Over the last fifty years, we have witnessed a great deal of interest in addressing workplace and societal issues that are related to reducing gender and racial inequalities and various forms of discrimination. Words such as diversity and inclusion are now commonplace in many organizations’ vision and strategy statements, which set out initiatives to create more inclusive, representative, diverse, and multicultural workplaces.

There are many challenges involved in providing a diverse and inclusive organization, as the barriers are wide ranging, and they include cultural gaps between people with different ethnic backgrounds, negative attitudes, or stereotypes of various minority groups, organizational practices which reinforce systemic views concerning the prioritization of certain groups over others, and organizational cultures which are unwelcoming. These issues are faced by women, minority groups, Indigenous populations, people with disabilities, younger and older people, LGBTQ populations, and many other groups; however, these issues are most pressing for organizations whose frontline workers have clients who have been marginalized from society, and who have faced problems such as drug addiction, mental health issues, and homelessness. Some of the clients of these organizations have a deep distrust of mainstream governmental, police, and social organizations based on past encounters; thus, although ideas and practices for enhancing diversity and inclusion might seek to reduce barriers through equitable practices and multicultural training, the context surrounding the involvement of these people is often affected by a history of mistrust and abuse.

Most of the research and initiatives for improving diversity and inclusion are focused on organizations that function in mainstream society; hence, they focus upon various contexts concerning universities and the public and private sectors (Mor Barak et al. 1998; Nishii 2013; Broome et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019). Although there is some positive evidence to suggest that progress is being made (Dobbin et al. 2011, 2015; Jansen et al. 2014), there are many more reports that suggest the successes of these initiatives are mixed, unclear, ambiguous, or slow (Ghorashi and Sabelis 2013; Hur and Strickland 2015; Bell and Hartmann 2007; Quillian et al. 2017); for example, in one study, in a local government context, the goals of managing diversity were less likely to be achieved when the practices were adopted reactively, rather than proactively (Hur and Strickland 2015). An Affinity report (Affinity 2022) indicated that just 40% of companies offer Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion-related (DEandI) learning and development opportunities, and only 45% say that their workforce reflects the demographics of society. A McKinney report, comprising data from 2014 onwards, indicated that many companies illustrated little progress in terms of diversifying their leadership teams with women and minorities in the US and UK, although the business case for diversity remained strong (McKinsey and Company 2020).

Although there is a consensus that the climate for diversity and inclusion can be defined by the perceptions that members share (Jiang et al. 2022; Nishii 2013), the context and social environment required to achieve a climate of diversity and inclusion is less understood (Beus et al. 2021). Context is generally defined as the “situational or environmental constraints and opportunities that have the functional capacity to affect the occurrence and meaning of organizational behavior” (Johns 2017, p. 577). There is a growing understanding that context has an important impact on many facets of organizational behavior, resulting in many “anomalous findings which can affect the validity of research…” (Johns 2017, p. 580). In the same way, context is important for “… identifying boundary conditions of theories…” and recognizing a “trend away from universals and toward a more nuanced and contingent view of natural and social phenomena” (Johns 2017, p. 580).

There are three possible reasons as to why context is important for determining whether the climate surrounding diversity and inclusion initiatives is positive or negative. First, diversity targets might alter personnel decision-making, but they may also do little to change day-to-day relationships, which are the sources of discrimination between groups. With regard to these relationships, the context might suggest that people may hold onto their stereotypes and choose to work alongside people they have always worked with or socialized with after work (Green and Kalev 2008). Second, implementing diversity practices to improve the outcomes of historically disadvantaged groups might be resented by those who do not agree with these special programs, as they feel disadvantaged by them; thus, as a result, their negative stereotypes or biases against these groups might persist, or become even more negative. Third, some of the specific difficulties linked to the implementation of these initiatives might be linked to a context which shapes the climate and culture of the organization (Holmes et al. 2021; Mor Barak et al. 2016; Schneid et al. 2015).

To address these issues, this paper aims to provide a better understanding of how context might shape a climate for inclusion by examining the perceptions of people working in organizations that serve ‘non-mainstream’ parts of society, in particular, those working with Indigenous people and minorities. The grounded approach that we used, the Echo approach, comprises a series of questions that are aimed at identifying experiences where employees felt valued and more included, as well as experiences where they felt excluded (see Appendix A). This approach has a long history in understanding values and bridging racial relations, and it is connected to the group methods that were inspired by Kurt Lewin (Lewin 1947a, 1947b) and Alex Bavelas (1942). We found it particularly relevant because of its focus on understanding values and beliefs, which comprises the basis of a climate for inclusion. In the following section, we summarize different paradigms for diversity and inclusion, and we review how we conducted interviews that sought to identify experiences which defined a climate for inclusion.

2. Literature Review

Diversity and inclusion are terms which are often used interchangeably; however, their meanings are different (Shore et al. 2011). A recent systematic review of studies focusing on diversity and inclusion scales suggests that there are range of factors or dimensions that define inclusion and diversity separately, but there are very few studies that focus on both inclusion and diversity (Park et al. 2022). The diversity dimensions focus on the fairness of leadership and organizational procedures, whereas the inclusivity dimensions generally focus on being able to express one’s uniqueness and the feeling of being valued by a group (Nishii 2013; Jansen et al. 2014; Ashikali et al. 2020; Pearce and Randel 2004). Other inclusion dimensions emphasize specific group practices, workgroup uniqueness, and belongingness (Nelissen et al. 2017; Chung et al. 2020); therefore, inclusiveness is an entirely different concept from diversity.

The underlying implication in some studies is that diversity initiatives might fail to produce the new capabilities and synergies that might be gained by focusing on inclusion, or on developing an inclusive environment to support diversity (Nishii 2013; Holmes et al. 2021). Moreover, if we want to address the lack of diversity in organizations, and realize the potential benefits that are linked to a diverse workforce, there is a need to create an environment or climate which encourages inclusiveness (Nishii 2013; Shore et al. 2011).

This literature review summarizes the key studies defining diversity and how perceptions of fairness comprise an important aspect of the context that enables or hinders the development of a positive, diverse climate. A climate supporting diversity recognizes fair practices and how people are treated; this is symbolic of the manner in which the organization respects them and their place in the organization. A climate of inclusion recognizes the uniqueness of people and it prioritizes a strong sense of belonging. The literature concludes that a climate of inclusion is heavily influenced by context; in other words, it is influenced by how employees feel in terms of whether they are valued, which is reflected in whether their uniqueness is appreciated, their long-term history within the organization, and their recent experiences within the organization’s culture. As such, this study sets out to define a climate for inclusion that is shaped by the culture (context) that people experience.

2.1. The Growth in Importance of a Diverse Workplace

A considerable period of time has passed since workplace diversity and inclusion appeared on our radar; it has heightened our awareness of the gaps, inequities, and barriers that exist for different groups. Addressing diversity and inclusion-related issues requires us to become more aware of that which divides people and how it might be linked to strongly held values and beliefs concerning what is right and wrong.

Although many people have a positive view of the value of diversity, there are also difficulties with regard to confronting the dominant ideologies and social practices that exist. For example, in an in-depth interview-based study of four metropolitan regions in the U.S., when asked about the positive aspects of diversity, people talked about being personally accepted and being part of a harmonious group; however, even though they had a positive vision of diversity, they provided vivid examples of prejudices they experienced, challenges in responding to others, and biased assumptions of other people. In accordance with a prevailing societal view, they suggested that they are “happily blind to problems of race and inequality” (Bell and Hartmann 2007, p. 907).

Addressing diversity issues often involves initiatives that aim to provide fairer and more equal representation, and that intend to eliminate barriers. For example, initiatives aimed at improving diversity might involve changing procedures, legislation, and rules to provide fairer and more equal representation for groups that have been previously disadvantaged. This might require shaping recruitment and selection practices so that they are more representative of society at large; this is based on the assumption that this will improve cultural awareness and understanding (Thomas and Ely 1996). Other initiatives might seek representatives from different designated groups to illustrate that the organization is sensitive to specific groups; however, the women and minorities who are appointed might feel that that they were appointed because they are “the designated person”. Initiatives for eliminating barriers might focus on initiatives that increase participation in educational programs (Morven and Cunningham 2020; Thomas and Ely 1996).

Fairness is a key concept underlying most of these measures concerning diversity, whether they are related to fairness of leadership (Mor Barak et al. 1998; Buttner et al. 2012; Ward et al. 2021) or organizational fairness (Chrobot-Mason 2003; Buttner et al. 2012; Mor Barak et al. 1998); thus, the concept of diversity has generally evolved to recognize the “varied perspectives and approaches to work that members of different identity groups bring” (Thomas and Ely 1996, p. 80).

2.2. Recognizing the Key Dimensions Concerning How Climate Supports Diversity Initiatives

There has been a great deal of interest in understanding the climate surrounding diversity, given that a procedural climate of justice is emerging. Climate is defined as “shared perceptions of team procedures” (Roberson and Williamson 2012, p. 688), “a group-level shared perception about the fairness with which a work group has been treated” (Yang et al. 2007, p. 681), and it comprises perceptions concerning the fairness of procedures, practices, and supporting interpersonal processes. As such, perceptions of fairness are an important aspect of the context required for developing a positive procedure climate of justice (Mossholder et al. 1998; Naumann and Bennett 2000; Yang et al. 2007). When group members feel that they are being fairly treated, the design of fair procedures is seen as symbolic of the fact that the organization respects their place and status. In many cases, fair procedures are thought to have an enduring quality; they are considered to be a symbol of what people agree with, and of what they perceive as important (Lin and Leung 2014; Yang et al. 2007).

Diversity climates refer to employees’ perceptions of the extent to which their leaders and organization encourages fairness and inclusion, both formally and informally in terms of their practices and procedures (Jiang et al. 2022). Diversity climates involve practices which encourage fairness and inclusion, wherein fairness requires the implementation of human resource practices and organizational procedures encouraging equality, and/or those which prevent inequality. At the individual level, a climate for diversity may be associated with an individual’s assessment of the extent to which their organization establishes and maintains a fair and inclusive climate; conversely, at the group level, diversity requires the shared perceptions of fairness, equity, and inclusion. (Jiang et al. 2022).

In terms of measuring the climate underlying diversity, studies have focused on teamwork and the ‘workplace voice’ (Jiang et al. 2022), team relationships (Roberson and Williamson 2012), and perceptions of fairness and inclusion (Jiang et al. 2022). A positive diversity climate can be illustrated by the treatment that people experience or feel; this is important for addressing gender and racial disparities (Gelfand et al. 2001; Thomas and Ely 1996). Moreover, this implies that a positive diversity climate is linked to employee satisfaction, commitment (McKay et al. 2009), and achievements, which might be measured in relation to performance and overall organizational effectiveness (Cox 1994).

Liao and Rupp (2005) identified three types of justice climates (procedural, interpersonal, and informational) with multiple foci (organizational and supervisory) (Liao and Rupp 2005). The overall favorability of a procedural justice climate has had an important impact on shaping attitudes; for instance, job satisfaction in financial service organization (Mossholder et al. 1998), employees’ tendencies to help in two large banks in the southeastern United States (Naumann and Bennett 2000), and commitment and citizenship-related behavior in 44 workgroups representing multiple organizations and occupations (Liao and Rupp 2005). It is also linked to a climate for diversity, as faculty members’ perceptions of procedural fairness and gender equity in a Midwestern US university were seen as being powerful factors in fostering inclusion and warmth between women and men (Maranto and Griffin 2011).

Several studies have reviewed the strength of procedural justice climates, and there are indications that the variation in strength of the climate in different settings is partially explained by the context. In particular, the context defining the climate might depend on the diversity of occupational or professional norms, a team’s history of working together or their expectations of working together in the future, and the degree to which one person might possess an inordinate amount of influence (Perringo et al. 2021; Hollenbeck et al. 2012). Other studies have noted the importance of context in understanding the relationship between team performance and absenteeism in a sample of manufacturing teams (Colquitt et al. 2002), and they also considered how unique variations in the workforce might affect the response to diversity (Boekhorst 2015).

In most cases, a climate of diversity describes perceptions of fairness and equity rather than perceptions of inclusion.

2.3. The Importance of an Inclusive View of Diversity and a Climate for Inclusion

To offer an explanation as why diversity efforts are not fulfilling their promises, Thomas and Ely’s seminal article, “Making Differences Matter: A New Paradigm for Managing Diversity”, suggests that diversity goes beyond “increasing the number of different identity groups’ affiliations on the payroll to recognizing that this is merely the first step” in understanding how these different perspectives can work together in a creative and positive manner (Thomas and Ely 1996, p. 80). They suggest that two perspectives have guided most diversity initiatives in the past: a discrimination-and-fairness paradigm and an access-and-legitimacy paradigm. The discrimination-and-fairness paradigm focuses on recruiting and retaining employees to meet the objectives of affirmative programs; they aim to provide fair and equitable treatment and meet the requirements of legislation. The access-and-legitimacy paradigm represents an effort to match the demographics of an organization in terms of its critical consumer or constituent groups. Although the discrimination-and-fairness paradigm might be related to the assimilation of different groups, the access-and-legitimacy paradigm encourages a celebration of differences in seeking employees to respond to unique demographics so that the organization’s demographics match those of its constituents (Thomas and Ely 1996).

Thomas and Ely (1996) presented an inclusive view of diversity—a learning-and-effectiveness environment—that is characterized by the belief that people’s diverse backgrounds can be a source of insight and creativity. Organizations working within the paradigm recognize that employees who make decisions and act based on their cultural background and identity are a source of additional creativity and innovation because of the perspectives that they can offer. To effectively identify diversity resources within a learning-and-effectiveness paradigm, employees are encouraged to understand differences and commit themselves to respecting and valuing the processes which exist in other cultures.

Many concepts that are related to defining inclusion build upon Ely and Thomas’ integration-and-effectiveness perspective which suggests that individuals need to feel valued and respected and that they should be able to manifest their uniqueness (Ely and Thomas 2001). Diversity has generally been concerned with preventing inequality and inequity by designing fair practices. Inclusion, and a climate of inclusion, encourages initiatives for involving people and developing positive norms and cultures (Jiang et al. 2022). A high sense of belonging and of being valued for one’s uniqueness is seen as important to some researchers (Shore et al. 2011). The inclusion dimension of diversity involves the proactive integration of employees (Dwertmann et al. 2016), involvement in the decision-making process, access to information, and job security (Pelled et al. 1999). Building upon the “multicultural” view of an organization (Cox 1994), inclusive workplaces illustrate a collective commitment to integrating diverse cultural identities (Ely and Thomas 2001; Thomas and Ely 1996).

2.4. Recognizing the Importance of Context when Defining the Climate of Inclusion

Although many of the measures concerning the climate of diversity recognize fair practices and how people are treated (Gelfand et al. 2001; Thomas and Ely 1996), a climate of inclusion recognizes the uniqueness of people and their value in terms of encouraging acceptance and the expression of divergent points of view (Ward et al. 2021; Pearce and Randel 2004). Other studies highlight the opportunity to learn about different cultural backgrounds (Ashikali et al. 2020; Schneider et al. 2017).

Studies that focus on a climate of inclusion illustrate dimensions such as group involvement (i.e., feeling part of informal discussions and respect of others), influence on decision-making (i.e., ability to influence decisions, having a say), and access to information and resources (i.e., feedback from boss, having the materials to complete a job) (Mor Barak and Cherin 1998). Nishii (2013) suggested three dimensions which focus on: equitable employment practices (i.e., for fair promotions and performance reviews), the integration of differences (i.e., a non-threatening environment where people can reveal their “true” selves in a culture in which employees appreciate the differences that people bring to the workplace), and inclusion in decision-making (i.e., where employees feel diverse perspectives are valued and sought). Ashikali and Groeneveld (2015) highlighted the importance of the integration of differences and inclusion in the decision-making process.

Many of the studies focused on organizations and groups in mainstream society. Studies were conducted in a variety of contexts. They involved university students (Mor Barak et al. 1998), people in a biomedical company (Nishii 2013), other university-based settings (Broome et al. 2019), and multiple contexts concerning industry and the public sector (Li et al. 2019).

In a systematic review focused on understanding the measures and dimensions of inclusion and diversity, Park et al. (2022) indicated that nine out of thirteen studies were from the U.S., and the remainder were from the Netherlands. Most of these studies were management and psychology-based, and they were focused on the organizational level; conversely, the inclusive studies were focused on the group level. As such, the context shaping the climate of diversity might describe the shared perception of the extent to which an organization encourages fairness and inclusion (Jiang et al. 2022); conversely, a climate of inclusion welcomes the differences that people from different groups bring to the workplace, wherein employees feel their perspectives are valued and sought after (Ashikali and Groeneveld 2015; Nishii 2013). As such, inclusive climates not only include fair procedures, but they make the effort to involve people in forming their collective identity. It is a model of integration which recognizes and rewards variability; it is not an assimilative environment in which non-dominant groups conflict with the values of the norms of a dominant group (Nishii 2013).

In most cases, the context defining the environment is an important moderating force underpinning how climate is defined. As such, context often explains the differences between hypotheses, or reasons that a conventional hypothesis might offer unique findings, as researchers try to respond to anomalies that need to be considered in different educational, public, and private organizations (Johns 1993, 2001, 2006, 2017).

Context, based on the Latin “to knit together or to make a connection”, can also provide a way of linking “observations to a set of relevant facts, events, and points of view…” (Rousseau and Fried 2001, p. 1). It may be suggested that if we do not understand and respond to the group context, we might fail to develop a climate that is relevant for that group. In other words, groups shape the behavior and feelings of their members, and the forces within the context of the group are powerful in terms of their ability to shape how the group members’ behaviors are constrained by the social pressures surrounding a motivational climate, as well as the pressures placed upon completing the group’s purpose (Lewin 1947b, 1951; Burnes 2004). In particular, the work of Kurt Lewin illustrated how groups shape the behaviour of their members, and that it is often fruitless to concentrate on changing the behavior of individuals as they are constrained by group pressures to conform” (Lewin et al. 1939; Burnes 2004, p. 983).

Although there are a range of factors to consider when attempting to understand the contexts of a particular setting, three factors which might be significant include: the demographic profile of the group, the long-term history of the group, and the short-term history of the group illustrated in recent key events or experiences. The demographic profile of a group or organization might illustrate the fact that certain groups might comprise mostly women, men, they might have an equal distribution of men and women, or they might illustrate a wide or narrow representation of people with different ethnicities. Unique contexts that are defined by one demographic might be illustrated by the police or fire organizations, blue collar labor groups, and some business organizations; these groups have been composed of mostly males. Amongst nurses, primary school employees, and social work organizations, these groups have been mainly composed of females.

Long-term history is important for many people; for instance, women who have long histories of gender-defined situations wherein they were given minor subordinate roles because of their gender. In the same way, people of different ethnicities have been affected by traumatic events such as the Holocaust, the abuses experienced in residential schools, and the internments of certain nationalities during wars. Some of these groups might experience reminders of this history, such as when Indigenous people in several locations found hundreds of unmarked graves at some of the locations of former residential schools.

Context can also be shaped by events that people recently experienced; this comprises their short-term history, which provides vivid illustrations of how people are treated or valued. These events might result from managerial, employee, or client-based incidents which affect motivation and relationships, the way the work is being conducted, or traumatic events relating to the treatment of minorities. For example, an employee’s claim concerning mistreatment by a manager can echo throughout the organization for years, thus affecting the level of trust that employees have in the organization, and their anger might be reflected in performance reviews, which might provide stories of managerial insensitivity and a lack of flexibility.

In the following paragraphs, we describe our research procedure which sought to define how a climate of inclusion might be linked to the contexts of organizational members working within those organizations.

3. Research Methods

In our research, we sought to gain a better understanding of the dimensions that define a climate that encourages inclusiveness. Our work sought to implement the following diversity objectives: (i) recruiting minorities in a large police organization; (ii) recruiting indigenous people in a probation department; (iii) defining initiatives for indigenous people and minorities in a non-profit service organization; and (iv) supporting minorities and indigenous people in a provincial social service agency. All studies involved a similar qualitative methodology and they sought to understand ways of developing an inclusive environment by responding to the values of employees or clients. The following sections provide a review of the general methods.

3.1. Design

There are various research designs that seek to understand the personal values that are important to a culture or work setting. These include designs that emphasize Indigenous values and protocols, as illustrated by efforts to decolonize research (from conventional Western methods) (Simonds and Christopher 2013; Smith 1999; Wesley-Esquimaux and Smolewski 2004). Other examples emphasize collaborative and participative principles when illustrating a group’s historical context (Tuhiwai-Smith 2008; Minkler 2004; Scott 2010, p. 75). For example, there is a Hawaiian methodology called Māʻawe Pono, wherein the researcher is involved with the culture, and they take time to understand the culture’s ancestral knowledge (Kahahalau 2017). Another method encourages narratives and storytelling to reveal culture and context (Hunt 2014, p. 27) while placing an emphasis on “community” over the “individual” (Roy 2014, p. 118; Johner and Maslany 2011, pp. 151–52); this works on the assumption that Indigenous knowledge is relational.

Similarly, the Echo interview approach seeks to reveal the values, beliefs, and nuances of different peoples and groups within a culture. This method is connected to the group methods inspired by Kurt Lewin (Lewin 1947b), the general assumptions of Gestalt psychology (Wertheimer 1959), and the direct work of Lewin’s student, Alex Bavelas (Bavelas 1942). This method was developed to systematically reveal the values, beliefs, and nuances of different peoples and groups; moreover, it has been used in studies involving Indigenous populations (Havighurst and Neugarten 1955) and people in other cultures (Bridge and Heller 1968). Regarding the Echo method, people are asked multiple questions; for instance, questions concerning what is good and bad, what they approve or disapprove of, or what satisfies or dissatisfies them. The questions seek to find examples of experiences which illustrate the values and working assumptions of a culture, given that the evidence suggests that this is a more reliable indicator of a person’s motivations and possible actions. One general Gestalt principle, which suggests that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”, is implemented by asking additional questions; these questions connect the responses to the person’s history or context. That is to say, understanding a comment is not enough to know a person’s values, as values are connected to the person’s context and culture, which manifests in the experiences, histories, and people who are sources of approval and disapproval (Bavelas 1942; Cunningham 2001).

3.2. Procedure and Participants

Two of the studies sought to try and identify ways in which to recruit minorities and indigenous people, whereas the other two studies focused on developing initiatives involving indigenous people and minorities. The samples were taken from a medium-sized police department (n = 20), a provincial probation department (n = 8), a non-profit society (n = 4), and a provincial organization. The small sample sizes reflect the small number of indigenous people or minorities in these organizations; for example, we interviewed 8 probation officers which represented nearly all the indigenous employees in a government department of 350 probation officers. See Table 1 for a summary of the four organizations.

Table 1.

Organizations and Samples Involved.

3.3. Interview Process

The principles of the Echo method were applied in all four studies, in the way we structured the interviews and analyzed the gathered information. One of the features of this method is the use of general open-ended questions which gave respondents the freedom to identify the values and histories that were most important to them. Additional questions gathered information on concept-based areas such as recruitment, support of group members, key motivators, and other areas. Examples of such questions were:

“Could you describe a positive experience you had in your setting where you felt really motivated and proud to be part of the group (organization or setting) which stands out as most important to you?”

“Describe a not-so-positive experience where you felt disengaged or troubled by something that occurred in the group (organization). This experience might have troubled you because you experienced a very non-positive emotive state.”

Our interview questions added elements of Flanagan’s (1954) critical incident technique when eliciting examples and experiences; this was intended to improve validity, as demonstrated by its ability to define competencies and behaviors related to managerial performance (Boyatzis 1982), and emotional and social competencies related to teams fighting wildfires (Boyatzis et al. 2017). These types of questions illustrate a moderate degree of reliability and predictive validity (Cunningham and MacGregor 2006).

Another set of questions focused on concepts related to recruitment and retention, culture, diversity, and inclusion, leadership and diversity, support from team members and colleagues, diversity training, community relations, and personal autonomy. During the information gathering process, we added probes to obtain more vivid details, and to obtain reactions to the experiences elicited. As such, in the area of recruitment, the semi-structured interview design asked for examples or incidents that people experienced or observed which inhibited or enhanced workplace diversity and inclusion, or which they felt were positive or negative experiences. Other questions asked for ideas concerning the enhancement of the recruitment process, retaining employees, and for developing a workplace where they felt a sense of belonging and a feeling of being valued for one’s uniqueness.

3.4. Analysis

We read through and highlighted phrases that stood out in order to “get a feel for the data”; then, we sorted all the comments within the various conceptual areas (i.e., recruitment and retention, community relations) into different themes to illustrate the number of people making comments within each theme. The results illustrate different themes within different concept areas, and the tally of responses represented the number of individuals offering comments within each theme (Cunningham 2001; Boyatzis et al. 2017).

3.5. Generalizability of the Results

One of the obvious limitations of this study concerns the small convenience samples; however, in all cases, we did endeavor to test the saturation principle, which is often used as a gauge for the quality of the responses. That is, theoretical saturation is a point wherein no additional data collection would produce new information on the themes that summarized the information. Here, a researcher might be confident that the general area being investigated is saturated, and that new interviews will not produce other themes or categories (Glaser and Strauss 1967, p. 65). This is a rough guide, and there is no true test to ascertain when this might occur. In their summary concerning the progression of theme development, Guest et al. (2006) provide experimental evidence to suggest that saturation can occur with as few as twelve interviews. In this study, the interviewers continually tested the saturation principle and challenged the adequacy of the sample by seeking people who potentially represented a different perspective for each theme. Moreover, although the interviewer felt somewhat confident that saturation was reached in two of the four studies, we have to be mindful that we were not able to fully test this for the third or fourth study (the non-profit society, which supported the information gathered in the other two settings).

4. Findings

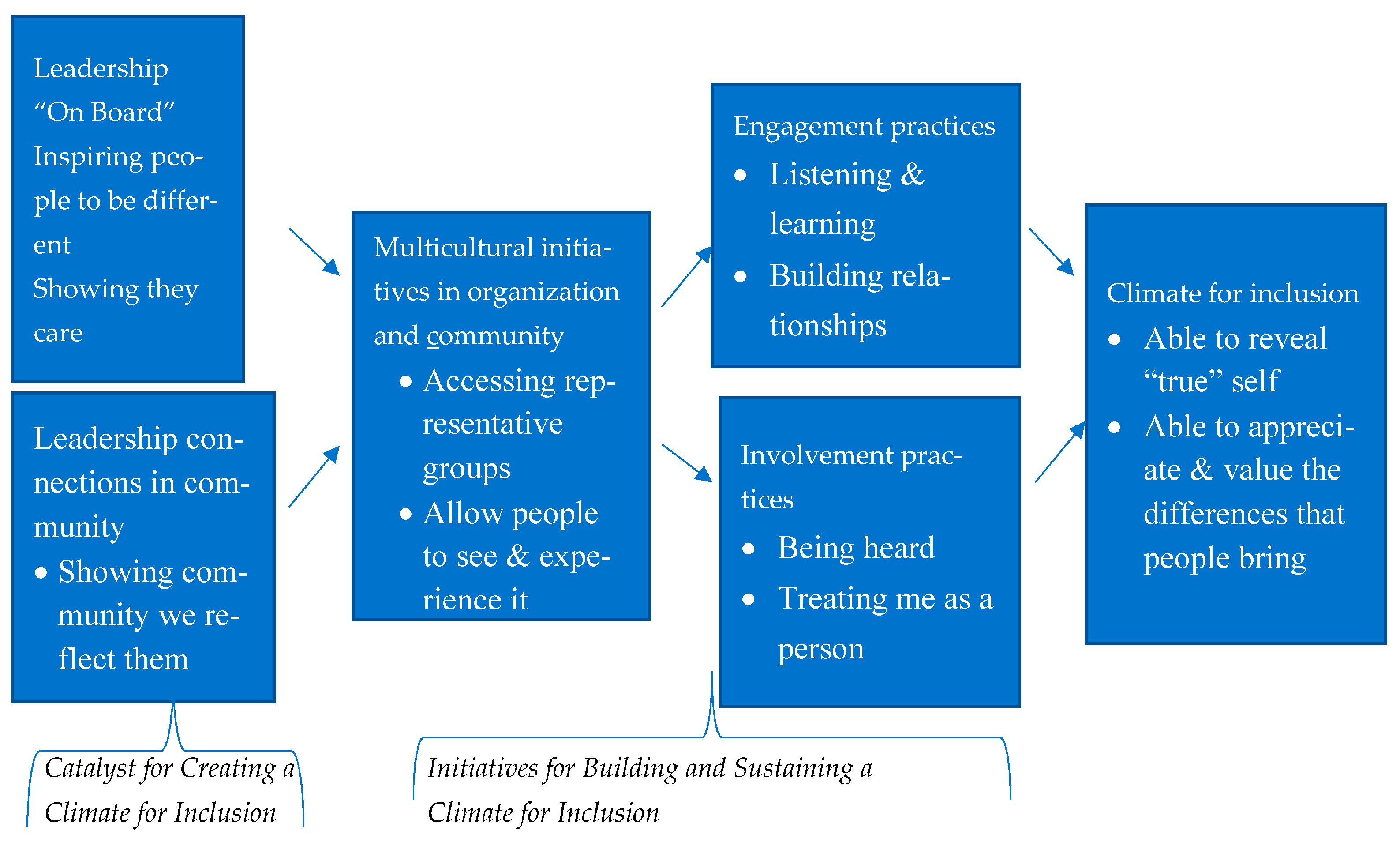

Figure 1 illustrates a framework which emerged as we categorized the responses from our interview data. The framework suggests that developing an inclusive climate is partially related to what leaders can do when acting as a catalyst for change. In addition, the initiatives introduced encouraged multiculturalism and they engaged with and involved people. The first two themes—leadership and community connections—might describe the catalysts which are important for developing a climate of inclusion.

Figure 1.

Catalysts and Initiatives for Building an Inclusive Climate.

4.1. Leadership and Community Connections

Table 2 and Table 3 illustrate leadership practices which act as catalysts for change when creating a climate of inclusion. In this regard, leadership initiatives concerning “being on board,”reaching out, and connecting to the community were illustrated in all four settings. Leadership was seen as one of the first key factors that help create a climate for inclusion, as leaders can inspire others and show their commitment to inclusive initiatives. As one provincial employee indicated:

“The biggest thing for me is a supportive manager and executive… The times I haven’t wanted to stay have been when my manager is not supportive or has made my job more difficult… Not only not helping, but making it harder… For me, I want to know if something goes wrong, they’ll have your back.”

Table 2.

Having the leadership be “on board.

Table 3.

Having leadership reach out in the community defines values of inclusiveness.

This comment, among others in Table 2, highlighted the importance of “supportive leadership in providing a bit of safety.” Moreover, comments stated that leaders needed to be “inspirational and motivational in getting commitment to diversity”, and they should be dedicated to “keeping things moving, and not dying on the vine”.

The leadership comments, in all cases, but especially with regard to policing and probations, suggest that there was a distinct lack of diversity in the top leadership roles, and any attempt to “fix” that through tokenism would be a disservice to all and would be very apparent to the membership. These comments pointed toward the need for the leadership to provide support and implement inclusion practices, in addition to raising awareness of such practices. Some respondents involved in policing perceived a distinct disconnect between the people working on the street and those in headquarters; this was partly reflected in statements suggesting that the “Chief and top Headquarters staff are rarely seen by those at lower levels”, as “they do not attend patrol briefings nor are they seen in areas where members work and engage with each other.” Moreover, it was also reflected in comments arguing that leaders needed to “make sure diversity and inclusion issues were reflected in policies and practices”, so that all staff are clear on priorities.

The comments from the two service organizations provide examples of inclusive experiences related to being proud of an organization wherein the “leadership illustrates diversity” and where supervisors are willing to engage in “tough conversations about how to connect to the community”. The negative comments, which might hinder inclusiveness, relate to “not having support from the people above” and a “lack of dedication and intention to inclusive practices”. One employee noted frustrations with a leader who did not illustrate this dedication:

“Things die on the vine in our organization because we don’t have support from the people above… if it was important to our Executive, they would make diversity recruitment a strategy that is actually beneficial and show their dedication and intention to recruit a broad range of diverse employees.”

The second important catalyst or enabler, shown in Table 3, points to the leadership’s ability to reach out to the community, which illustrates their commitment and interest in such practices. Across all four groups, reaching out was important for changing perceptions, and this was identified as being especially important in policing and probation organizations, as the long history of negative interactions with minorities and Indigenous people in these organizations may have led to negative perceptions. For example, a lack of trust and understanding of the police was identified as one of the major reasons that minorities do not apply for policing jobs. The perceived lack of trust that is generated by negative feelings towards the police was illustrated in areas where residents were more disadvantaged or had more interactions with the police. These experiences seem to have cultivated a perception that recruitment procedures have historically discriminated against minorities, women, and indigenous people.

The comments concerning reaching out to the community in Table 3 illustrate a desire to not only understand the community and its needs, but to take steps in creating partnerships and to reshape perceptions by adjusting the organization’s services to align with different community needs. In some cases, this might result in changing recruitment practices so that they are more easily accessible and so that cultural sensitivity is improved. This could be achieved by making the recruiting process less difficult and impersonal. One police interviewee, when offering suggestions on improving minority recruitment, suggested there was a need to be more proactive in day-to-day patrols, and that opportunities to spontaneously interact with visible minority groups, who have unfavorable views of the police, should be taken. “There was an officer in the north end who was doing a patrol and saw some kids playing basketball. He joined in and someone from the media took a picture, and the community loved it….” “Take a kid on ride-along”. The Indigenous probation officers talked about “going to high schools” and “forming partnerships with Aboriginal organizations”, and individuals in service organizations suggested they might “design programs and services which were accessible to unique needs” and that they should “take steps to build trust”.

Employees in the Probation Department and non-profit organizations indicated that they made efforts to create partnerships in the community in that they reached out to Indigenous organizations in the community. They offered suggestions for organizing community dinners, and they designed programs and services so that they were more accessible. On the other hand, employees in the provincial agency illustrated examples of experiences where exchanges felt as though they were “going through the motions” rather than “engaging with an explicit purpose of attracting Indigenous people”. They felt that more inclusive practices required the creation of an environment which illustrated “respective communications” and where they did not have to feel defensive when “justifying why we need to be a diverse employer”.

4.2. An Inclusive Climate Based on Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism means different things to different people; however, for these individuals, it was mainly linked to their involvement with Indigenous people and visible minorities. Most of the comments on multiculturalism concerned cultural awareness and experiences that might encourage mindfulness of different cultures in an inclusive environment, wherein diverse backgrounds are a source of insight and creativity (Thomas and Ely 1996). The findings in Table 4 underline the idea of tolerance and awareness of different cultures, in addition to experiences which can enhance this. For example:

Table 4.

Initiatives for developing multicultural practices in organizations and the community.

- -

- Diversity is celebrating our differences. Most helpful have been small staff celebrations of different holidays in different cultures, rather than hearing reports from trainers about their histories of being bullied, harassed or not respected.

- -

- We had what they called a Readiness Program and we could spend our day anyway we wanted to related to cultural awareness. So, a bunch of us spent half a day at a Sikh Temple and another half a day at a Mosque. What a good idea, I thought. Spend time in other cultures.

- -

- I believe, that as an Indigenous person, that you can’t understand who I am unless you become involved in what I do and that is becoming involved and attending something that represents my history… we learn by observation and experience…we learn if you’re attending a feast or if you are attending a cultural event. It’s like you’re observing what’s going on and you can see and feel out things and make connections.

Underpinning this theme is the assumption that it is far better to experience multiculturalism rather than be involved in a training program which tells people about the importance of multiculturalism. Table 4 illustrates experiential events involving organizations and community members, and it notes how these events shaped people’s perceptions of diversity and inclusion. In policing, for example, which might traditionally be perceived as an organization of white males, the community connections illustrated a need to show that they “represent different genders and cultures”, “respect culture and community practices”, and “want to participate in different cultural events involving Indigenous people, Muslims, Hindus, and other minorities.” “If you want to understand minorities and their needs in law enforcement, then, we have to see the culture…eat chicken feet, light lanterns…during Ramadan. We could have a feast at sundown and invite Muslims….”

Similar comments concerning multicultural experiences were made by interviewees in the non-profit society and in the Provincial Service organization.

“[Speaking about a previous work environment] The closest I saw to a team with norms of valuing culture and safety… people who were hired because of their identity… they were allowed to be who they were. Openly gay, Muslim, Sikh, Indigenous…they were allowed to bring their culture to work, and not asked to leave it at the door… There was no policy, it just happened and evolved over time.”

In the probation organization, there were suggestions to build partnerships with Indigenous organizations and with Elders, Chiefs, Council, and Women’s groups. One person suggested that connecting to the community was an honor and something to look forward to in building relationships with others.

“I like to participate in this kind of thing (cultural) because it’s an honor… like when we installed a residential school monument in the park at the St. Joseph Mission. I was acting Local Manager and I invited another staff member and we shut the office so we could take part in this.”

The two service organizations offered similar comments on the value of being involved in and experiencing multiculturalism, remarking that it was able to “provid[e] a perspective on history as well as their experiences in other local bands”. Moreover, of utmost importance for these people was the desire to “have impact” and be “involved in a valuable change process”. There was a desire to connect with racialized groups to understand their perspective on a “safe space” wherein there is “solidarity and inclusion” among the staff, and where they can express their unique cultures. Others commented on their passion for working in an environment where people felt “embraced” rather than “isolated”. For others, this was reflected in “defining diversity events, activities, and experiences which emphasize multiple cultures” and can thus help develop a “better cultural understanding of a wider variety of clients rather than being entrenched in events not considering diverse cultures.”

Table 4 summarizes examples of multicultural perspectives offered by employees in the provincial service organization, and they provided a wider definition of diversity that extends beyond the inclusion of just one group.

- -

- Our diversity paradigm was ‘Indigenous only,’ which isn’t diversity… I didn’t know of any openly queer, trans, disabled, or any other kind of diverse staff, with combinations of identities.

- -

- Other racialized people don’t have that kind of safe space, solidarity, and inclusion we need. We’ve moved forward an inch, but there are still a lot of people left.

- -

- We are now more intentional about… creating spaces for differences in backgrounds beyond Indigenous and non-Indigenous…

Employees in the non-profit society suggested that it would be useful to gain other perspectives “to learn about their history and experiences of living in other local bands”. “Aren’t we a lot smarter for having more points of view?” Thus, while most of the comments on multiculturalism focused on creating a greater sense of awareness, some comments from the two service organizations indicated that multiculturalism has a broader definition to involve many cultures in encouraging new perspectives and in creating space for others beyond just Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

4.3. An Inclusive Climate Supporting Involvement and Engagement

The fourth set of findings in Table 5 features two themes illustrating how inclusiveness can be enhanced by engaging with and involving employees. Engagement involves providing opportunities to employees, and thus encouraging a person’s commitment and energy at work; this is akin to Kahn’s original definition of engagement as “the harnessing of organization members’ selves. As such, in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performance’ (Kahn 1990). Although disengagement is considered to be the withdrawal of oneself from work, employee engagement concerns how employees experience their work, and whether they are ‘fully there.’ This transcends affective commitment, or emotional attachments based on shared values and interests (affective energy). It also transcends job involvement, which might be another facet of engagement (cognitive energy). It reflects the “passion” and willingness to embrace an organization’s tasks, aspirations, or assignments as one’s own. Engagement has been found to be higher in employees of the public sector vs. the private sector, and it is higher among public sector managers when compared with their employees.

Table 5.

Initiatives for engagement and involvement in creating positive relationships.

The findings in Table 5 indicates that the work environment creates a sense of “camaraderie”, which encourages people to come to work, and it makes them feel that they are a part of a “wonderful team” where they “do a lot of wonderful things”. As illustrated in the study of Indigenous probation officers, this is partly due to relationships where people are continually “listening and learning”, and “building better relationships” within the work environment. Other comments indicated that the organization encouraged them to have a “positive mindset” which made them “feel [as though] you want to be there”, “feel valued”, and “know that there is no other place where I could have this kind of impact”.

Although engagement concerns the harnessing of one’s self, involvement concerns becoming part of a team and “developing a trusting relationship”, “sharing”, “expressing oneself”, and “feeling that I am being heard”. In a police organization, this is reflected in the day-to-day feedback of supervisors; here, there is constant communication and an effort made by the supervisor to “know my culture and understand where I might be coming from”. In the probation department, the environment was described as a place for “sharing ideas, initially, where there are common interests” and “focusing jointly on identified problems like Indigenous health, school participation, and recruitment in government organizations”. Other comments from the service organizations related to wanting “opportunities to express oneself and be heard”, “deconstructing the hierarchy to where we can get to the root of the issues”, and “creating opportunities to be involved”.

Several comments highlight what happens when involvement is perceived to be tokenistic, and where there is no evidence of follow through.

- -

- The overarching view is that we encourage inclusion and provide a lot of different ways to interact. But it’s all prescribed… There’s no time for true reflection of our struggles as an organization or the work we do. We have… a lot of fluffy, feely stuff, but we aren’t really good at examining critically what we do as an organization.

- -

- There are weekly all-staff calls,… there is a lot of time and space for staff views and sharing, but I don’t think our environment is safe space for a lot people… If we’re encouraging inclusion, maybe, look at different ways it can be done.

In other cases, interviewees indicated that they offered their ideas and were not being recognized for them.

- -

- I wrote emails to my manager and provided my thoughts, but I never received a reply. Then, I’d noticed that my ideas were spoken about in a staff meeting and used in developing an initiative… I’m not credited with the idea… This has happened a bunch, too much for it to be a coincidence. My ideas are incorporated, but not through discussion, dialogue, or engagement. They just take them and call them their ideas.

5. Discussion

The results profile the nature of an organizational climate of inclusion, which partially supports what Ely and Thomas (2001) define in their learning and integration paradigm, and which Nishii (2013) operationalized, with regard to the integration of differences and the prioritization of inclusion in the decision-making process. Nishii’s work (2013) suggests that a climate of inclusion can be an important aspect of the implementation of gender-based diversity and inclusion initiatives, and that it might be a major factor in reducing any negative feelings concerning conflicts (regarding relationships) and satisfaction rates (Nishii 2013). Her study is unique in that other researchers, using metanalysis and other methods, were unable to find any moderating factors that explained how to diminish the negative consequences of relationship conflict (De Dreu and Weingart 2003). Nishii’s hypothesis suggests a “climate for inclusion moderates the relationship between gender diversity and relationship conflict. As such, lower levels of relationship conflict are experienced in gender diverse groups that enjoy highly inclusive climates” (Nishii 2013, p. 1758).

The results in this study provide a different framework for defining an inclusive climate amongst minorities and indigenous people. The concepts relied upon open-ended interviews and inductive processes that concerned defining concepts and measures that reflected contexts, rather than deductive processes, as illustrated in other studies (Nishii 2013; Park et al. 2022). In this study, possible concepts and measures that could define inclusiveness for minorities and Indigenous people are as follows: (i) leadership practices supporting inclusiveness within the organization; (ii) leadership engaging in the community and becoming community-centered; (iii) multicultural practices as a foundation for defining diversity; and (iv) relational practices engaging with and involving staff. Table 6 illustrates these concepts and possible measures, and they echo the words and sentiments given by people in their interview responses.

Table 6.

Catalysts and initiatives for creating and maintaining a positive inclusive environment.

The first two dimensions concern developing an inclusive climate, and thus they focus on leadership and community engagement. Leadership is central for creating a catalyst for inclusion which is supportive of diversity initiatives, and which illustrates that the leadership is “on board”. This advocates the need for leaders to recognize the learning opportunities of a diverse workforce, and to communicate these values and intentions in vision and mission statements. This also means connecting with the community for feedback and ensuring programs and initiatives are responsive. Initiatives for implementing these ideas require policies and practices to illustrate that the workplace fosters a climate that is supportive of diversity, which must be clearly understood by minority and Indigenous people.

The third dimension focuses on how the program is structured to create an inclusive climate by integrating and building upon differences. This concerns multicultural practices in the community as well as in organizational arenas; for instance, staff could involve themselves in community cultural events, which would indicate their respect for different cultures. Hence, a multicultural perspective is not just inclusive of one group, and it illustrates a culture of diversity for various cultural groups (Indians, Muslims, Jewish, Indigenous people, etc.). Illustrating multicultural practices within an organizational context, and within this dimension, involves ensuring that staff have the opportunity to be involved with different cultural groups in the organization. This means organizing diversity events, activities, and experiences which allow for a better cultural understanding of a wider variety of clients, and not just one culture. This also means creating a space in which different groups are safe, the safety of which must be illustrated.

The fourth dimension describes examples of relational practices as a foundation for engagement and involvement. Although engagement initiatives are designed to develop a positive emotional state, involvement is concerned with giving people a voice. These findings suggest that engagement and involvement are different practices. Engagement is akin to ‘internal motivation’, which describes a self-directed or autonomous behavior that realizes intrinsic or other higher level needs or callings. One way to improve employee engagement is through work experiences which are intrinsically motivational and which engage people at higher intellectual levels; these experiences may occur in the community or organization, and an example of such an experience may involve taking responsibility for projects or for designing initiatives. Involvement is an entirely different process, and it is illustrated when staff share ideas, when they jointly focus on problems of common interest, and when they take steps to make people aware of how different cultures define a problem. Other facets of Involvement include creating a space for people to feel safe.

This section provided insight into how we might define the components of a climate of inclusiveness for people working in non-mainstream parts of society, particularly those working with Indigenous people and minorities. Future studies could conduct a similar experiment among other members of the population.

6. Conclusions

We used the Echo approach to inductively identify experiences where participants felt included, as opposed to where they felt excluded. Our results are based on interviews from four different organizations: a medium sized police organization, a provincial probation department, a non-profit society, and a provincial service organization. The experiences that were revealed in the interviews fell into four categories that were related to developing a positive climate for inclusion, as follows: (i) leadership supporting inclusiveness within the organization; (ii) leadership connecting with the community; (iii) initiating multicultural practices as a basis for defining diversity and inclusion within the organization and community; and (iv) relying on relational initiatives to encourage engagement and involvement.

The present study suggests that the leadership initiatives—being “on board” and an ability to connect with the community—are catalysts for change. The focus on the implementation of multicultural initiatives is a way of illustrating how people are valued within the inclusive climate. The initiatives for involvement and engagement represent ways of helping members within these organizations to create and maintain a climate where they feel valued and are able to speak out.

This conceptualization of a climate of inclusiveness has greater applicability in contexts that include first line responders, as compared with contexts that work with people on the fringes of society. The people in these organizations were mostly advocates, care givers, and they were required to be responsive to people in different cultures; thus, it might seem natural that they identified leadership and organizational practices which were relational and sought to build trust. Even police officers in law enforcement roles identified that building trust and connections were key to building inclusiveness.

This paper’s conceptualization of the climates of diversity and inclusivity is different from other studies which highlight dimensions such as group involvement, the ability to influence decisions, and access to information and resources (Mor Barak and Cherin 1998; Park et al. 2022). Other defined dimensions include equitable employment practices, the integration of differences with regard to working in a non-threatening environment where people can reveal their “true” selves, and inclusion in the decision-making process where employees feel as though their diverse perspectives are valued and sought after (Nishii 2013).

We are especially mindful of the small samples we studied in each of the four organizations, and thus, we understand that it is impossible to make generalizations. Future research might assess whether the dimensions and measures in our framework add to our understanding of an inclusive climate in other organizational settings. Although our dimensions and measures might provide some direction for future research, in terms of the types of organizations we worked with, we suggest that we should always be open to methods which seek to understand different contexts, and which allow individuals and groups to define the climate most relevant to them. As such, individuals in a group are constrained by group pressures to conform, or pressures from the context, which defines the culture and climate of a group (Lewin 1947b).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted within the ethical policies of the University of Victoria Office of Research Services.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Requests for information should be sent to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. History of the Echo Approach

“Echo has been used for groups including employees, students, nurses, psychiatric clients, and many others, in a wide range of geographical and cultural settings. It would be fair to say that over the years, Echo became known, mainly by word of mouth, as an innovative and appealing but definitely off-beat survey technique” (Beavin Bavelas 2001).

The word “Echo” might be an unfortunate choice of a word to define the Echo Approach, which was originally defined by Bavelas in the 1942. Since that time, the word has been used to name several tools and techniques. A Google search will find various ways to describe the term; it is used as the name of outdoor power equipment, an echocardiogram, and an echochrome video game, created by Sony for their PlayStation 3. Using library search tools, the term Echo approach will generate articles related to a tool used for MRIs (i.e., multi-echo spin echo MRI), various applications in health (i.e., Environmental influences on Children’s Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program), and a communication satellite experiment launched in 1960 and 1964. Even the keywords “understanding values using the echo approach” will generate a range of different views pertaining to the term ‘echo’, many of which are not related to its original history, and which are connected to health-related research (i.e., in bringing together communities of learners of health providers).

Studies on the Echo method, as originally articulated by Alex Bavelas, can be found by using keywords such as: “Bavelas Echo Approach”, “psychology echo approach”, “Bartol and Bridge, Echo Project, General Research Corporation” and “Cunningham and Echo approach”. A Google search of the following authors will generate results relating to Project Echo from 1966 to 1969 with the General Research Corporation. See: Bartol and de Mille (1969); Milburn et al. (1968); Bartol and Bridge (1967); Bridge and Heller (1968); De Mille (1970); Bartol and Bridges (1968). Other related sources include: Schaefer et al. (1980); Cunningham (2001); Cunningham and MacGregor (2006); Alojairi (2010); Darling (2020).

The Echo Approach, as defined here, is historically connected to Alex Bavelas and some of the work he conducted in a group with Kurt Lewin, when many of the ideas pertaining to group decision-making processes and communication emerged. A significant period of experimentation took place as part of a contract with the Department of Defense in the 1960s (from mid-1966 to early 1969), at the General Research Corporation; this project was part of the Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA). In this work, Alex Bavelas (who worked at Stanford) was asked to explore the potential of the technique for investigating the ideologies of groups.

The name ECHO was originally chosen because of the interest in its possible prominence as an ECHO message-generation technique, with respect to its ability to gather information concerning the underlying ideology or culture of a group. The name ECHO was not meant to be an acronym, but rather, it was seen as a tool for acquiring information from members of a group, processing the information, and (similarly to an echo) returning the information to other members of the group in a way that described their true values, assumptions, and nuances; hence, the information gathered “echoed” members of the group in that it described them in a valid way (Bartol and de Mille 1969, p. ii). As such,

The ECHO method is a way of observing, quantifying, and describingthe patterns of value and influence that are felt, verbally expressed, and often acted on in human society. Understanding these patterns helpsus to understand, communicate with, and be effective in a particulargroup or culture.(Bartol and de Mille 1969, p. 1)

Over the years, different researchers have used Echo-like questions that might align with their intentions of gathering information, and thus “echo” the values and nuances of the people being studied. The following subsections review the different types of Echo questions, questions for defining values of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, questions concerning understanding the influence of people similar to you, questions concerning the influence of other people in other roles, questions on helpful events or experiences, and questions on the valuation of events or experiences.

Appendix A.2. Areas or Variables Sought in Different Types of Echo Questions

The decision to rely upon the Echo approach in our interviews was driven by its usefulness over its history in terms of its ability to capture the deeply held biases, values, and beliefs of people of certain groups. It can also provide a possible explanation as to why they act in certain ways or voice strongly held opinions or points of view.

In the original article describing Echo, regarding its application for studying non-Mennonite and Mennonite children (Kalhorn 1941, 1944), the goal was to determine the sources of approval and disapproval among school children using the following types of questions:

“What could a child of your age do at school that would be a good thing to do and someone would praise him/her?”“Who would praise him/her?”“What could a child of your age do at school that would be a bad thing to do and someone would scold him/her?”“Who would scold him/her?”

The pairs of questions were repeated several times with different wordings in a controlled procedure involving children in two schools who were in the 4th to 8th grades. (Bavelas 1942). Later, studies used the method to compare Mid-western white children with children in ten American Indigeous communities (Havighurst and Neugarten 1955). There were also studies Jewish–Gentile relations and efforts to respond to problems within different minority groups (Marrow 1969; Lewin 1946).

Years later, in an extensive period of experimentation on the Echo method, other types of questions were developed, thus increasing the number of ways that questions could be asked. That is, the question might relate to: the articulation of values and beliefs, the role of the respondent (i.e., a person similar to you, a person you would like, a person you would not like, etc.), events (i.e., things to think about, events which would be enjoyable/unenjoyable), different types of valuation (i.e., good/bad, like/dislike), reinforcement or agency (i.e., reinforcement is the consequence of behavior; agency is the relationship between cause and effect), source (i.e., working conditions, accidents, sports), and additional contexts (i.e., past or future). This gave rise to questions such as:

When have you felt most motivated (or, demotivated) in your work and energized (disenchanted) by what you did for (yourself/someone else)? Describe an example?

What are things you might do for your community which would make you feel proud? Why or why might make you feel proud of what you did?(Bartol and de Mille 1969; Milburn et al. 1968; Bartol and Bridge 1967; Bridge and Heller 1968; De Mille 1970; Bartol and Bridges 1968; Schaefer et al. 1980; Cunningham 2001; Cunningham and MacGregor 2006).

Appendix A.3. Questions Seeking to Define Values of What Is Good or Bad

The original work defining Echo when investigating moral ideology focused on values and nuances. The questions asked were examples of good behaviors and they were distinguished from bad behaviors. The responses were separated into categories of good and bad behaviors (Beavin Bavelas 2001; Kalhorn 1944), with good being the opposite of bad. In a study of American white and Indigenous children, researchers suggested that there was no psychological distinction that separated the positive and negative comments (Havighurst and Neugarten (1955). Good and bad were sorted together into a single category, most of which contained logical opposites (e.g., “helps with chores”, “refuse to help chop wood”); however, the convention which seemed to have developed concerned the fact that the separation of good and bad did not result in comments where good is the opposite of bad. In open ended responses to value-based questions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, some of the items could be paired with logical opposites and some could not (De Mille 1970).

Examples of General Valuation questions from original Echo studies include:

- -

- “What are things you most enjoy doing which makes you feel good?”

- -

- “What do you dislike doing which makes you feel good?”

Appendix A.4. Questions for Understanding the Influence of People Similar to You (Role of Respondent)

The role of the respondent might point to the person (you), a person similar to you, a particular class of person (i.e., age group, minority), a person you would like, or a person different to you (Bavelas 1942).

Examples for understanding influence, from Flanagan’s (1954) Critical incident technique (p. 332):

- -

- “Think of a time when a foreman has done something that you felt should be encouraged because it seemed to be in your opinion an example of good foremanship.” (Effective—slight deviation from norm.)

- -

- “Think of a time when a foreman did something that you thought was not up to par.” (Ineffective—slight deviation from norm.)

- -

- “Think of a time when a foreman has, in your opinion, shown definitely good foremanship—the type of action that points out the superior foreman.” (Effective—substantial deviation from the norm.)

- -

- “Think of a time when a foreman has, in your opinion, shown poor foremanship—the sort of action which if repeated would indicate that the man was not an effective foreman.” (Ineffective—substantial deviation from norm.)

Appendix A.5. Questions Understanding the Influence of Different People

It is sometimes useful to vary the role of the respondent and include other sources of influence such as managers, colleagues, friends, among many others.

Examples based on Flanagan’s questions (1954) are as follows:

- -

- “Could you provide an example of a time your leader did which was extremely helpful in leadership in helping the platoon perform well?”

- -

- “Can you provide an example of a time when your leader did something which was very unhelpful and put the platoon in danger?”

Examples from Flanagan’s (1954) Critical incident technique, p. 342

- -

- “Think of the last time you saw one of your subordinates do something that was very helpful to your group in meeting their production schedule.”(Pause till he/she indicates he/she has such an incident in mind.)

- -

- “Did his/her action result in an increase in production of as much as one per cent for that day?—or some similar period?”(If the answer is “no”, say)

- -

- “I wonder if you could think of the last time that someone did something that did have this much of an effect in increasing production.”(When he/she indicates he/she has such a situation in mind, say)

- -

- “What were the general circumstances leading up to this incident?” (Flanagan 1954, p. 342)

Appendix A.6. Questions Seeking to Understand the Importance of Different Events or Experiences

Echo questions might focus on seeking events that illustrate behaviors, potential activities, or events.

Examples based on Echo Studies included:

- -

- “What might be good things to do to others to be helpful in the community?”

- -

- “What are things people might do which would be unhelpful to people in the community.”

Appendix A.7. Questions on the Valuation of an Event or Experience

The valuation of the event relates to what people find good or bad or what they like or dislike. Valuation might also refer to what illustrates a person’s confidence or what they might fear (Milburn et al. 1968; Kalhorn 1941, 1944).

Examples based on Herzberg (1968) questions were used to define motivational and hygiene-based factors, as follows:

- -

- “Can you think of a time when you were exceptionally motivated or when you experienced a very positive emotional state at work?”

- -

- “Can you think of a time when you were exceptionally unmotivated or when you experienced a very low emotional state at work (which bothered you a lot).”

References

- Affinity. 2022. The Future of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion 2022. Available online: https://www.hr.com/en/resources/research_jp1hf9nt.html (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Alojairi, Ahmen S. 2010. Project Management: A Socio-Technical Perspective. Ph.D. thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ashikali, Tanachia, and Sandra Groeneveld. 2015. Diversity management in public organizations and its effect on employees’ affective commitment: The role of transformational leadership and the inclusiveness of the organizational culture. Review of Public Personnel Administration 35: 146–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, Tanachia, Sandra Groeneveld, and Ben Kuipers. 2020. The role of inclusive leadership in supporting an inclusive climate in diverse public sector teams. Review of Public Personnel Administration 41: 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartol, R. P., and G. Bridge. 1967. Project Echo. Santa Barbara: General Research Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, R. P., and R. de Mille. 1969. Project Echo. Final Report. Santa Barbara: General Research Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, R. P., and R. G. Bridge. 1968. The Echo multi-response method for surveying value and influence patterns in groups. Psychological Reports 22: 1345–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavelas, A. 1942. A method for investigating individual and group ideology. Sociometry 5: 371–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavin Bavelas, J. 2001. Foreword. In Researching Organizational Values and Beliefs: The Echo Approach. Edited by J. B. Cunningham. Westport: Quorum Books, pp. vii–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, R. G., and J. F. Heller. 1968. Echo—Vietnam. Santa Barbara: General Research Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Joyce M., and Douglas Hartmann. 2007. Diversity in everyday discourse: The cultural and consequences of ‘happy talk. American Sociological Review 72: 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beus, Jeremy. M., Erik C. Taylor, and Shelby J. Solomon. 2021. Climate-Context Congruence: Examining Context as a Boundary Condition for Climate. Performance Relationships 105: 1332–56. [Google Scholar]

- Boekhorst, Janet A. 2015. The role of authentic leadership in fostering workplace inclusion. Human Resource Management 54: 241–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, Richard E. 1982. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance. New York: John Wiley& Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Richard, Kiko Theil, Kylie Rochford, and Anne Black. 2017. Emotional and social intelligence competencies of incident team commanders, fighting wildfires. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science 53: 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, E. Holly, Leonora Billings-Harris, and Kevin B. Lowe. 2012. An empirical test of diversity climate dimensionality and relative effects on employee of color outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics 110: 247–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, Bernard. 2004. Kurt Lewin and the planned approach to change: A reappraisal. Journal of Management Studies 41: 977–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, Benjamin J., Ian Derk, Robert J. Razzante, Elena Steiner, Jameien Taylor, and Aaron Zamora. 2019. Building an inclusive climate for intercultural dialogue: A participant-generated framework. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 12: 234–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]