Abstract

This study explores the most significant changes experienced by small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic. It reveals the SMEs’ strategies to survive and prosper amid the crisis. These actions are becoming increasingly invaluable and crucial for entrepreneurs in the heritage of humanity, such as Indonesian batik, who must stay in business to preserve national culture. This study conducts a systematic literature review of 42 relevant articles published between 2020 and the present and furthers the investigation using the Most Significant Change technique, involving in-depth interviews with 15 SME entrepreneurs. The results show that Indonesian batik SMEs struggled during the pandemic and experienced at least a 70% revenue reduction. Those who survived implemented retrenchment, persevering, and innovation strategies to achieve their short- and long-term goals. A temporary exit strategy was also applied in which business actors engaged in a different, more profitable business while awaiting normalcy. This study also found that true entrepreneurs’ qualities, namely creativity and resilience, emerge in exceptionally difficult business situations.

1. Introduction

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic affected all economies, particularly emerging countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) received a report of a new pneumonia case of unknown cause on 31 December 2019 and declared a COVID-19 pandemic on 11 March 2020. This pandemic has disrupted the economic and national stability of almost all countries. The acceleration of the outbreak was triggered by climate change, urbanization, a lack of water, and poor sanitation (World Bank 2020, 2021a). Many countries are now facing a more substantial wave of the pandemic and must struggle with high economic inflation.

Before the pandemic, Indonesia was an emerging economy that experienced remarkable growth (consistent growth of 5–6% annually) (World Bank 2021a). The country’s economic growth fell by 2.2% by 2020 due to the pandemic but is forecasted to improve by 2021 (World Bank 2021b). In Indonesia, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have contributed significantly to Indonesian GDP, that is, 59% of the GDP (Kaushik 2019). These businesses provide 97% of their employment in Indonesian society. These figures far exceed those of neighboring countries, namely Malaysia (33% of GDP and 58% of employment), the Philippines (34% and 58%, respectively), Singapore (47% and 70%), and Thailand (37% and 81%) (Kaushik 2019). Given their scale and capital ownership, Indonesian SMEs have been the most affected by the pandemic.

Even today, with the improving situation and the positive economic turn, SMEs are struggling. This study investigated Indonesian batik SMEs. Batik is an Indonesian cultural heritage site with philosophical meanings and symbols (UNESCO 2019). It is a craft that has become a part of Indonesian culture with high value and fusion of art. Batik is also one of the largest foreign exchange earners and was designated a masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Most batik entrepreneurs started a business as a legacy from the family or established a business because of skills and values that had been passed on over generations. In addition to their passion for batik art, they also have an immense sense of responsibility for preserving batik according to Indonesia’s local wisdom.

The batik industry has made a significant contribution to the national economy, including the one that has created many job opportunities. This is reflected in its contribution to foreign exchange through export achievements for the January–July 2020 period of USD 21.54 million, which is an increase compared to the first semester of 2019, which was valued at 17.99 million (Indonesian Ministry of Industry 2020). This sector has absorbed 200 thousand workers from 47 thousand business units spread across 101 regional centers in Indonesia (Indonesian Ministry of Industry 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, most batik SMEs have experienced a drastic decline in sales. The Chairman of the Association of Indonesian Batik Craftsmen and Entrepreneurs reported that after approximately seven months of the pandemic, SMEs with a capital scale below IDR 50 million (approx. USD 3480) were almost entirely out of business. Hundreds of thousands of laid-off batik artisans switched professions into fishermen, farm laborers, construction workers, factory workers, or hawkers (Maulana 2021). By changing professions, these entrepreneurs and artisans face difficulty returning to their initial fine batik crafting skills. It could even be that the tradition of batik in a particular area of Indonesia has completely disappeared (Maulana 2021).

This study attempts to address critical questions related to the pandemic’s impact on the sustainability of Indonesian batik SMEs. Their actions may be on par with those of small business owners, who rely on a wealth of knowledge and skills inherited from their ancestors. This study was guided by two research questions.

- What most significant changes do Indonesian batik SMEs experience due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What countermeasures do these SMEs apply to survive and sustainably prosper?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2, next, briefly synthesizes a literature review of SMEs’ strategies during a crisis. Section 3 and Section 4 detail the methodology and results related to Stage 1 (Systematic Literature Review/SLR) and Stage 2 (Most Significant Change/MSC). Section 5 discusses the implications from both theoretical and practical perspectives. Section 6 concludes with suggestions for future research and contributions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crisis Strategies for Business

The literature on crisis management has grown and includes multiple dimensions (Kraus et al. 2020). Various studies have examined organizations’ responses to economic crises (González-Bravo et al. 2018) and natural crises (Chang 2010; Marshall and Schrank 2014). Marshall and Schrank (2014) proposed a systemic approach to examining the impact of disasters on business actors, particularly small businesses, by considering the interrelationships and dependencies between business actors, families, and communities. This view is essential for understanding the struggles of small businesses to overcome disasters and fully recover. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency in Marshall and Schrank’s study, recovery occurred when the entire system returned to normal conditions. This condition is subjective, depending on the business actor. Drawing from Chadwick and Raver (2018), an entrepreneur’s positive attitude psychologically affects the perception that stressors (such as disasters) can be overcome, thus making him more proactive and resilient in business. This drives resilience, namely “the ability to adapt to the changes brought about by the disaster in a creative way” (Marshall and Schrank 2014, p. 609).

Furthermore, businesses respond to crises in order to survive. Previous studies have identified business strategies for survival, namely reducing costs and assets and changing the product/market focus (Hofer 1980). Wenzel et al. (2020) identify four strategies for SMEs: persevering, retrenchment, innovation, and exiting. Similar to Hofer (1980), Wenzel and colleagues found that firms use efficiencies during their struggle to survive (i.e., retrenchment). Retrenchment is a powerful measure that is not recommended in the long term because it can damage systems within the company. A better strategy is persevering in which a company maintains its status quo and mitigates risk. Innovation is a sustainable strategy for long-term survival. A company must design and implement new things to surf business dynamics and outperform competitors. A company’s inability to do one or overcome a crisis results in business closures.

2.2. Pandemic Impact on SMEs and Their Survival Strategies

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, almost all countries have experienced an impact on their respective economies. Countries with SMEs as economic supporters, especially developing countries where SMEs account for up to 80–90% of the economy, are severely affected by social mobility restrictions (El Chaarani et al. 2021; Rahman et al. 2022; Laorden et al. 2022). SMEs experience a significant impact due to tight capital, limited resources, inability to secure the supply of raw materials, and sometimes the obligation to pay debts. On one hand, SMEs are more agile and flexible in maneuvering without too much bureaucracy. However, this type of business does not have sufficient resources or networks to implement its strategies.

The literature finds that SMEs engage in diverse activities to survive during a pandemic, such as adopting marketing or process innovation (El Chaarani et al. 2021; Fabeil et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2022), reducing employees or working hours reduction (Arslan et al. 2022), adjusting supply networks (Fabeil et al. 2020), and obtaining financial grants from the government or other external parties (Arslan et al. 2022). Scholars also suggest that SMEs adopt digital technologies to improve their ability to survive (Adam and Alarifi 2021; Zutshi et al. 2021) and capture broader customer markets as well as to improve business performance and gain competitive advantage (Hidayat et al. 2022).

Prior literature regarding the impact of the pandemic on SMEs and their strategies has studied developed countries such as the U.K. (Keogh-Brown et al. 2020) and the U.S. (Bartik et al. 2020; Katare et al. 2021). A growing number of studies have conducted similar investigations in emerging countries, such as China (Dai et al. 2021), Vietnam (Le et al. 2020), Malaysia (Islam et al. 2021), the Philippines (Laorden et al. 2022), and Jordan (Al-Hyari 2020). However, there is still a call for research in the context of developing countries (Islam et al. 2021; Qehaja 2021) because SMEs contribute significantly to their GDP; therefore, their survival is critical.

The unexpected yet positive impact of the pandemic is the acceleration of digitalization in business. A survey by McKinsey (2020) showed that the Asia-Pacific region experienced the highest acceleration, a 4-year leap, compared to other regions, which took only three years. This rapid technology adoption not only happens to large companies but also to SMEs as well (Zamani 2022). The OECD (2021) report shows that 70% of SMEs are increasing their technology use for businesses compared to before the pandemic. Digital transformation improves SMEs’ business performance through technology adoption, digital skills, and other strategies (Hidayat et al. 2022; Teng et al. 2022).

3. Methods

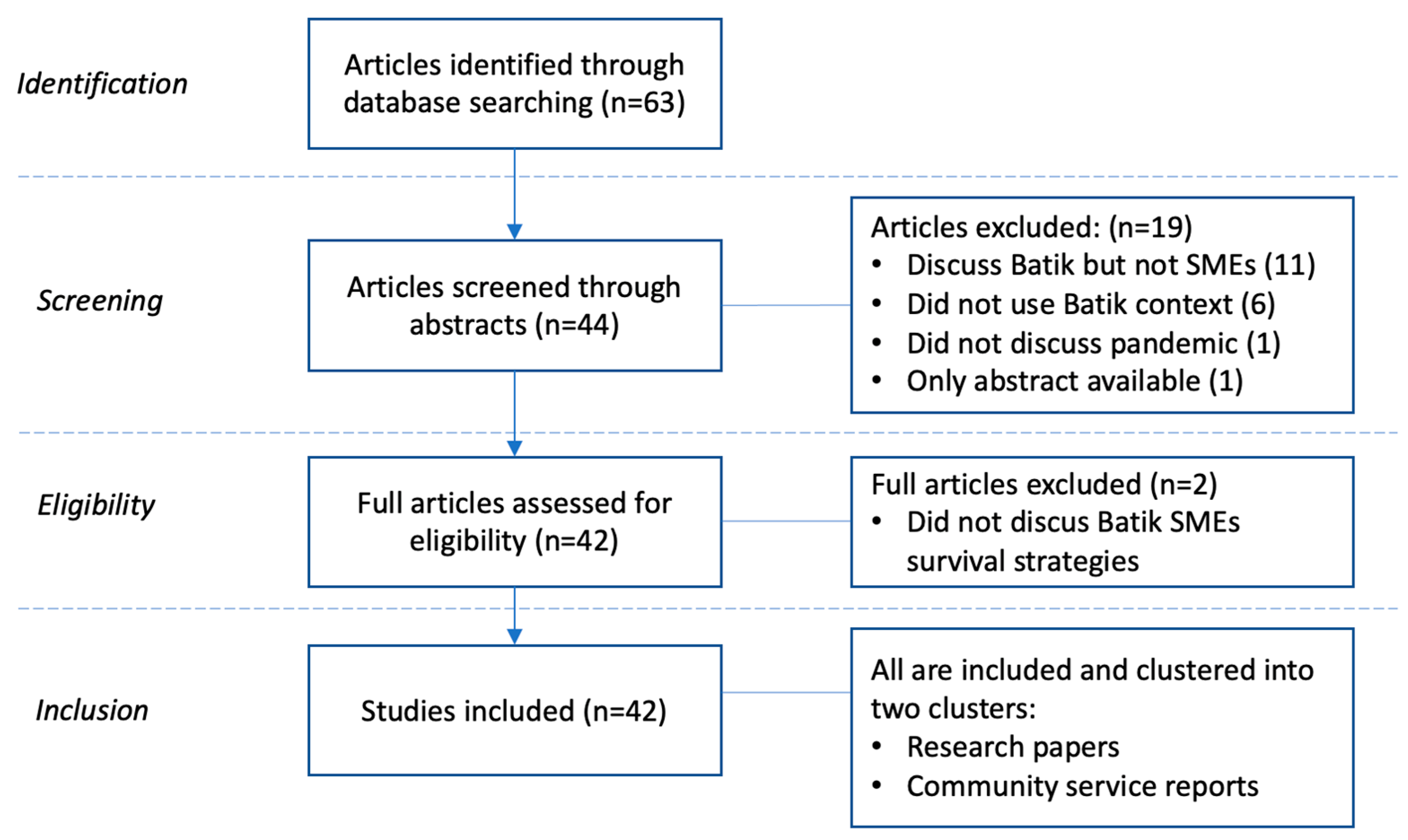

To address these research questions, this study explores the findings from the existing literature. We adopted the guidance of Xiao and Watson (2019) for (1) literature search and evaluation and (2) data extraction and analysis. The systematic literature review process is described in detail below, and the protocol is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature Search and Assessment based on Xiao and Watson (2019).

3.1. Systematic Literature Review: Literature Search and Evaluation

We searched for articles using EBSCOhost, Scopus, and Google Scholar. EBSCOhost and Scopus have been used extensively in high-quality academic papers. We used Google Scholar to search for and extract national publications. The search was narrowed to articles written in English or Bahasa Indonesia published between 2020 and 2022. We included papers published in any academic format, such as research papers, conceptual papers, book chapters, theses, or dissertations.

We searched for articles using broad keywords: “pandemic”, “SMEs”, “surviv*”, “strateg*”, “survival strategy”, “crisis strategy”, and “batik”. We used similar keywords in Bahasa Indonesia to ensure that national publications were incorporated. Google Scholar produced 57 results, EBSCOhost showed 0 (zero) results, and the Scopus database yielded six results. We extracted 63 studies included in the initial review.

Two researchers read all abstracts and excluded 19 papers that were not specifically related to the research question. The researchers thoroughly read the 44 papers. Two articles were further excluded as they did not investigate the strategies of batik SMEs during the pandemic. After discussing the results of the remaining 42 articles, two researchers decided on two broad clusters, which were based on the purpose of the article: empirical research and community service reports. The researchers retained community service reports because they provided valuable descriptions of SMEs’ efforts during the pandemic. Figure 1 presents a systematic review of the relevant literature.

Subsequent to the Systematic Literature Review, we validated the results with a field study using the Most Significant Change (MSC). MSC is essentially a monitoring technique for new programs or policies and for assessing or evaluating the results and impacts of a program or a certain condition (Davies and Dart 2005; Wilder and Walpole 2008). The current study employed MSC, as this method can capture the effects of any striking situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic. MSC can accurately identify noteworthy changes because data are gathered directly from business actors affected by the pandemic.

3.2. Unit of Analysis

This study investigates the crisis strategies of Indonesian batik SMEs. This type of business is unique because apart from applying the principles of a profit-seeking enterprise, it also has a social mission to preserve batik as a cultural icon. Batik art has been present in the Indonesian archipelago for many years. In 1817, batik became known in Europe through the book History of Java by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the British governor of Java. The book was archived at the Rotterdam Ethnic Museum (Ayuningtyas et al. 2021).

This study set the firm level as the unit of analysis and gathered data from actors owning batik small or medium-sized businesses. We used the SME criteria stated by the Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 20 Year 2008 for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. The criteria set small and medium enterprises as entities with a net worth of more than IDR 50,000,000.00 (50 million rupiahs or approximately USD 3442), up to a maximum of IDR 10,000,000,000.00 (ten billion rupiahs or USD 688), excluding land and buildings for business, or having annual sales of more than IDR 300,000,000.00 (300 million rupiahs or USD 20,654) up to IDR 50,000,000,000.00 (50 billion rupiahs or USD 3.4 million).

Through the SLR stage, we found that Java Island is the largest batik-producing region in Indonesia. Therefore, we focused on this island and set three different areas of Java to capture the variances. Four researchers collected data by directly interviewing the owners (face-to-face mode) whose businesses ranged from small to medium. In this study, the researchers confirmed that the business belonged to the small or medium enterprise range but did not differentiate the findings from these two categories. Table 1 presents the profiles of the participants.

Table 1.

Participating SMEs and Informants’ Details.

3.3. Most Significant Changes: Procedure

The MSC technique can deeply explore what is happening and how it impacts a community or business society (Dart 2000). As argued by Yunus and Ernawati (2018), “[t]he MSC systematically collects pieces of evidence of real changes which are often neglected or ignored in general monitoring techniques” (pp. 1920–2921). This study adopted the MSC technique described by Davies and Dart (2005) in the following stages.

First, we define the scope of the change to be explored. The change captured was the COVID-19 pandemic, which the Indonesian government officially announced on 11 March 2020. Second, we contacted owners of batik SMEs in Java to ask for their willingness to participate in this study. We obtained contacts from the batik association and obtained more contacts from those willing to be interviewed. To ensure that business owners understand what has happened to their businesses during the pandemic and their efforts to stay in business, we selected business owners who manage day-to-day businesses and do not merely provide capital. This arrangement is common for all SMEs, so we had no trouble finding informants.

We contacted 17 SMEs within three months (mid-December 2021 to early March 2022), but we interviewed only 15 owners. Two owners declined because of their busy schedules. For those willing to participate, interviews were conducted on-site (usually in showrooms or workshops). All interviews were recorded with the informants’ consent and lasted approximately for 30–60 min.

Third, the researcher converted the recording into a one-page story: one per participant. The story typically consists of one paragraph of the business and the owner’s profiles and one to two paragraphs describing the changes in the business due to the pandemic, the survival strategies, and the lessons learned by the owners. The last paragraph concludes with one of the most extraordinary changes that now characterizes owners or their businesses compared with before the pandemic. Finally, four researchers held a meeting to discuss all the stories. The findings were tabulated and compared to those of a systematic literature review.

4. Results

4.1. Systematic Literature Review: Findings

Drawing from the 42 articles, the researchers extracted the following: (1) the purpose and findings of the study, and (2) SMEs’ actions and strategies to survive during the pandemic. We did not use sophisticated software for coding such as NVivo because the number of studies was limited and manageable.

After obtaining all the relevant information, four researchers discussed the content in two subsequent meetings. The first meeting involved discussions to unify the meaning of each interview transcript. The second is to reveal insights into batik SMEs’ strategies for overcoming losses during the pandemic. The findings are organized in Table 2. Similar strategies are grouped into categories that represents the SME’s way of survival.

Table 2.

Batik SMEs’ Strategies to Overcome Pandemic Impacts (Findings from SLR).

4.2. Most Significant Changes: Findings

It appears that the MSC method provides richer discoveries than existing literature, which primarily uses surveys or limited case studies. All actions taken by entrepreneurs to survive the crisis were coded as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the Most Significant Changes.

From the coding results, this study finds that batik SMEs have engaged in various strategies to survive the pandemic. Most of them took ‘emergency’ actions by reducing the ‘burden’ and liabilities in order to stay in business. SMEs were forced to lay off employees, especially when the government imposed large-scale social restrictions (or lockdowns). Some businesses have attempted to replace layoffs with employee housing or to reduce working hours. Others substituted raw materials with a lower quality for efficiency.

In addition, batik SMEs obtain soft loans from families or the government to strengthen their financial stability. Some SMEs apply price discounts to finished products to boost their sales. They also collaborate with other batik entrepreneurs to obtain raw materials from suppliers jointly. Coopetition (or collaboration with competitors) allows entrepreneurs to buy in large volumes and obtain better pricing. They engage in joint marketing through exhibitions (both online and offline, albeit restricted). Batik SMEs have also adjusted their business models to comply with the health protocols recommended by the government so that employees can still work safely.

Almost all batik SMEs innovate to survive. Innovation is beneficial not only for SMEs to survive amid a crisis but also to produce something new and sustainable. They created batik masks, tote bags, and prayer mats. They also made daily batik wears for mothers who worked from home (WFH), such as negligees or casual shirts. Inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic, an SME designed a traditional batik using motifs of the coronavirus. According to the business owner, this fabric design is in great demand and even exported to other countries.

Several notable phenomena have emerged from the strategies employed by SMEs. SMEs, which were initially sold from their shops or showrooms, started selling online and realized that online shoppers had slightly different needs (e.g., more fashionable and premium). While they sell batiks online (through social media and websites), a new business line emerges for certain segments. Finally, SMEs serve a new market and establish dedicated units to handle the online and existing market segments.

Furthermore, SMEs utilize batik scraps as bags or clothes to be more cost-effective. One SME reduced nightgown length to save fabric material or modified clothing with cheaper non-batik fabrics (e.g., denim). These tricks turned out to be a new profitable series of products for the company (i.e., retrenchment strategy progressing into innovation).

Another distinct finding is the ‘temporary exit’ strategy implemented by batik SMEs (i.e., business diversification). This action was momentary in ensuring the company’s cash flow, allowing it to pay the employees’ salary. During the pandemic, several SMEs sold non-batik products such as food and personal protective equipment, mainly for hospitals. Some side businesses are sustained, with the batik business remaining as the core.

Finally, this study also found another noteworthy finding from the most significant change: the direct impact of the crisis on entrepreneurs. Some business actors experienced powerful self-development: that is, increased creativity and resilience. One participant conducted a community development program related to batik during the pandemic. However, this aspect of self-development has not been discussed in previous research. We elaborate on these implications in the following section.

5. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has subverted the economies of various countries, still prevails, especially in developing countries where the economy is not well established or strong (El Chaarani et al. 2021). The impact is harsh, particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Therefore, many businesses on this scale cannot survive and eventually close their businesses (Bartik et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2022; Caballero-Morales 2021; Qehaja 2021). Studies on coping strategies during and after a pandemic have become increasingly relevant. More empirical research on survival strategies is needed, especially for SMEs (Adam and Alarifi 2021; Islam et al. 2021; Katare et al. 2021).

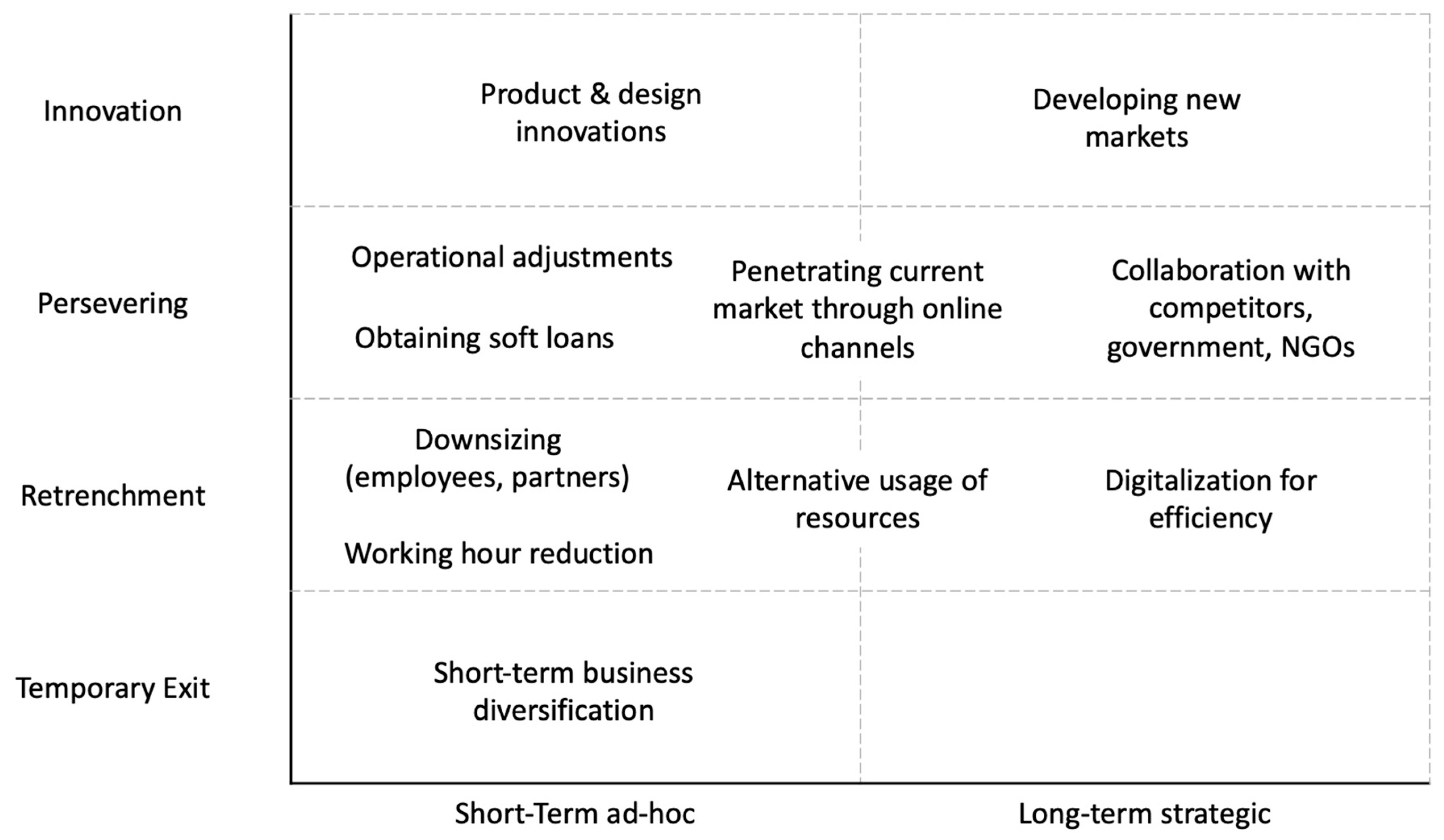

This study provides an overview of the strategies implemented by batik SMEs in Indonesia based on a systematic literature review and a qualitative study using the most significant change technique. Responses to pandemic crises are clustered based on Wenzel et al. (2020) and Kraus et al. (2020), namely innovation, persevering, retrenchment, and exit. This study included a short/long-term orientation for each response, as suggested by previous studies (Juergensen et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2022; Qehaja 2021). Figure 2 shows the survival strategies of the participating SMEs.

Figure 2.

Batik SMEs’ Strategies in Coping with the Pandemic.

Several techniques, such as price discounts, soft loans, downsizing, and reduction in working hours, are naturally short-term oriented. Some are medium-term, which are portrayed in the mid-line, such as selling through social media and websites for online shoppers and utilizing resources for multiple purposes. Selling through online channels has flourished into a market development strategy, resulting in new market segments for business.

Some of these actions are long-term strategic responses. SMEs engage in partnerships with the government and non-profit organizations for branding and sales cooperation. They also collaborated with other SMEs—an unthinkable action in the past. Figure 2 also shows a temporary exit, which is a unique finding for the most significant change. The ‘temporary exit’ should be part of the survival strategy because the owners did not plan to abandon their business entirely. Instead, they were engaged in works that utilized their skills and more profitable during the crisis.

5.1. Implications for Theory

Wenzel’s (2015) framework is comprehensive for mapping business responses in times of crises. This study shows all responses employed by batik SMEs, both ad hoc and strategic. The SMEs implemented four generic strategies: “revenue generation, product/market refocusing, cost-cutting, and asset reduction” (Qehaja 2021, p. 62). SMEs also seek soft loans from relatives or the government, which is in line with Arslan et al. (2022). This action is crucial because SMEs are vulnerable to financial risk (Cepel et al. 2020; Adam and Alarifi 2021).

All the SMEs in this study engage in innovation strategies, either innovating batik products or manufacturing processes. These results are in line with studies from, among others, El Chaarani et al. (2021) and Rahman et al. (2022). Considering that all the SMEs interviewed were innovating, we wonder whether businesses that went bankrupt innovated but failed or did not survive because of a lack of innovation. This speculation warrants further investigation.

Indonesian batik SMEs have implemented various simultaneous strategies to survive and maintain the cultural heritage inherited for generations. Batik entrepreneurs take pride in their mission to run businesses that preserve the Indonesian cultural identity. Many of them attempted to implement different actions during a pandemic, as commended by many scholars (Chesbrough 2020; Janssen and Van der Voort 2020; Rahman et al. 2022). Actions should be deliberately sketched for both short and long terms. Some strategies, particularly retrenchment and persevering, are challenging—if not unfeasible—to maintain for extended periods of time (Qehaja 2021; Wenzel et al. 2020). Batik entrepreneurs seem to comprehend this concept by combining short-term countermeasures (such as price discounts, layoffs, and obtaining soft loans) with medium- and long-term actions (new products and markets or digital transformation).

This study reveals another prominent theme in SMEs’ responses to SMEs: digitalization. Batik SMEs are transforming their business models to expand their market. They have designed a business website or set up a business account on social media to promote their batik products. They authorized payments through electronic banking or other cashless methods. This action significantly reduces transaction costs (OECD 2021). Batik entrepreneurs also performed digitization, such as turning various paperwork into paperless documents and ensuring that they were all connected using the Internet for simplicity, efficiency, and flexibility. They took advantage of various open-source applications that are widely available, such as website creation, batik product design, and work coordination. The pandemic has forced SMEs to accelerate digital transformation. This finding is in line with the suggestions of Adam and Alarifi (2021) and Zutshi et al. (2021) as well as predictions from Kraus et al. (2020) and OECD (2021).

Finally, this study also finds that soft competence plays a significant role during a crisis. The participants mentioned that the pandemic forced them to become more creative and persistent. They seek ways to survive by selling food, dishes, and personal protective equipment (i.e., a temporary exit strategy) while trying new product design alternatives. In other words, the entrepreneurial mindset and attitude increased because of the crisis, which is in line with Chadwick and Raver (2018) and Zutshi et al. (2021). Support from entrepreneurs’ close circles, such as family and direct communities, is pertinent to overcoming challenges and fully recovering from the impact of the pandemic. This finding is also consistent with that of Marshall and Schrank (2014), who suggested that families and social communities are pertinent in the recovery process of small businesses.

5.2. Implications for Practice

This study provides recommendations for future businesses. First, business actors can respond to crisis conditions by implementing efficiency (retrenchment), surviving through financial assistance and collaboration (persevering), and attempting to produce new products (innovation). Emergency countermeasures, such as downsizing and other efficiency measures, need to be taken early in the crisis but not for an extended period. Instead, business actors need to focus on innovation initiatives that extend their current portfolio with other, more primary, products for survival. For example, as clothes are not in demand during the pandemic, business owners could switch products with masks and praying mats that are essential (thus, more primary) during the strict social distancing period. These initiatives improve their market value.

Efficient programs such as digitization and digitalization can be utilized for business continuity if appropriately managed over the long term. The action could initially transform analog to digital form, thus reducing manual work. Business owners could extend further by streamlining the business process (such as sourcing the materials and conducting transactions with customers using their gadgets and open-source platforms). This strategy serves as a long-term strategy for the business viability

Furthermore, business actors must utilize all their assets to survive and thrive. The network is crucial capital in times of crisis. SMEs must work with suppliers, governments, non-profit organizations, and competitors to support each other’s business. Cooperation with competitors increases a company’s bargaining power when negotiating with suppliers and government. SMEs should maintain cooperation beyond the pandemic period to form long-term strategic alliances that benefit all parties.

When performing the survival strategies identified in Table 3, business owners should also be aware of any associated risks. Those risks might include acquiring additional resources for the innovation (such as a different set of materials for new designs), developing new competencies (such as the ability to cook, pack, and sell biryani rice, or the ability to create content for the social media ads), and losing skilled employees when the situation is back to normal. Therefore, business owners should consider the benefits over risks when selecting the most suited strategy.

5.3. Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study combines a systematic literature review with the most significant change to comprehensively capture the responses of batik SMEs to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is pertinent to acknowledge some limitations of the research design, which could serve as avenues for future research.

First, articles were extracted from three databases and search engines: Google Scholar, Scopus, and EBSCOhost, based on accessibility. As this is not ideal, we suggest that future studies extend this review by including other reputable databases, such as Web of Science. Moreover, future research could incorporate longitudinal studies to capture the dynamics of the SMEs’ strategies after the pandemic.

Second, the nature of a qualitative method encourages researchers to perform in-depth studies to address research questions; however, more is needed for generalization. This study interviewed 15 batik entrepreneurs in Indonesia, and the conversations reached saturation, in which the informants’ responses were repeated and did not result in new information. Future studies could validate these findings using a quantitative method to reach more business entrepreneurs. By employing the quantitative approach, future studies could also test the significance of each strategy on the SMEs’ long-term performance.

6. Conclusions

The UNESCO website states that “the craft of batik is intertwined with the cultural identity of the Indonesian people and, through the symbolic meanings of its colors and designs, expresses their creativity and spirituality”. All countries have traditional arts that have become an identity of their people and national pride. It is essential to preserve the tradition, craftsmanship, and symbolic meaning of this creativity.

This study investigates batik SMEs’ tactical and strategic actions and outlines them on a strategy map. All the participating business actors performed various survival strategies that could be categorized as retrenchment, persevering, and innovation. Some actions, intended for short-term business adjustments, have developed into long-term value creation, such as innovations, digitization, and moving toward to early phase of digitalization. Participating business actors also experienced improved entrepreneurship qualities such as creativity and resiliency. This study contributes to the literature by revealing the unique practices of SMEs and by inspiring other entrepreneurs to navigate the crisis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.Y. and E.E.; Methodology, E.N.Y. and E.E.; Software, E.N.Y. and K.Y.; Validation, E.N.Y., E.E., E.N. and K.Y.; Formal analysis, E.N.Y., E.E., E.N. and K.Y.; Resources, E.E. and E.N.; Data curation, E.N.Y., E.E., E.N. and K.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.N.Y.; Writing—review and editing, E.N.Y.; Visualization, E.N.Y.; Supervision, E.N.Y.; Project administration, K.Y.; Funding acquisition, E.N.Y., E.E. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to the anonymous reviewer(s) for the valuable and thorough feedback, which improved the contents of this paper. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the journal editor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam, Nawal Abdalla, and Ghadah Alarifi. 2021. Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the COVID-19 times: The role of external support. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 10: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiyanto, Mochamad Reza. 2020. Pemberdayaan usaha mikro dan kecil terdampak pandemi COVID-19 Desa Paseseh Tanjung Bumi Bangkalan. Community Development Journal 4: 178–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hyari, Khalil. 2020. Initial empirical evidence on how Jordanian manufacturing SMEs cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 19: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amijaya, Sita Yuliastuti, Tutun Seliari, and Kristian Oentoro. 2020. Pengembangan strategi pemasaran dan promosi produk UMKM di tengah pandemi COVID-19. Proceeding Senadimas Undiksha 365: 358–68. [Google Scholar]

- Andayati, Dina, and Yuliana Rachmawati K. 2021. Whatsapp sebagai alat bantu perdagangan Batik Kraton Yogya di era new normal. Prosiding Snast C-71–C-79. Available online: https://journal.akprind.ac.id/index.php/snast/article/view/3370 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Arslan, Ahmad, Samppa Kamara, Nadia Zahoor, Pushpa Rani, and Zaheer Khan. 2022. Survival strategies adopted by microbusinesses during COVID-19: An exploration of ethnic minority restaurants in northern Finland. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 28: 448–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuningtyas, Hanum, Lucky Wulandari, and Angy Sonia. 2021. Masker batik Betawi nan cantik: Peluang bisnis ekonomi kreatif di era new normal. SENADA (Seminar Nasional Manajemen, Desain Dan Aplikasi Bisnis Teknologi) 4: 423–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, Alexander W., Marianne Bertrand, Zoe Cullen, Edward L. Glaeser, Michael Luca, and Christopher Stanton. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117: 17656–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Morales, Santiago-Omar. 2021. Innovation as recovery strategy for SMEs in emerging economies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in International Business and Finance 57: 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepel, Martin, Beata Gavurova, Ján Dvorský, and Jaroslav Belas. 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the perception of business risk in the SME segment. Journal of International Studies 13: 248–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Ingrid C., and Jana L. Raver. 2018. Psychological resilience and its downstream effects for business survival in nascent entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44: 233–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Gracia Devina. 2021. Strategi Bertahan Industri Batik Tulis dan CapKampoeng Batik Laweyan Kota Surakarta di Tengah Pandemi COVID-19 Tahun 2021. Tugas Akhir pada Universitas Surabaya. Available online: http://digilib.ubaya.ac.id/pustaka.php/262099 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Chang, Stephanie E. 2010. Urban disaster recovery: A measurement framework and its application to the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Disasters 34: 303–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanifiyah, Milatul. 2020. Strategi Pengusaha Sentra Industri Batik Gayatri di Desa Ketanon Kec. Kedungwaru Tulungagung Dalam Menjaga Eksistensi Usaha di Tengah Pandemi COVID-19. Jurusan Ekonomi Syariah Fakultas Ekonomi Dan Bisnis Islam Institut Agama Islam Negeri Tulungagung. Available online: http://repo.uinsatu.ac.id/id/eprint/18677 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Chesbrough, Henry. 2020. To recover faster from COVID-19, open up: Managerial implications from an open innovation perspective. Industrial Marketing Management 88: 410–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Ruochen, Hao Feng, Junpeng Hu, Quan Jin, Huiwen Li, Ranran Wang, Ruixin Wang, Lihe Xu, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from two-wave phone surveys in China. China Economic Review 67: 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dart, Jessica J. 2000. Stories for change: A systematic approach to participatory monitoring. Paper presented at Action Research & Process Management (ALARPM) and Participatory Action-Research (PAR) World Congress, Ballarat, Australia, September 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Rick, and Jess Dart. 2005. The ‘Most Significant Change’ (MSC) Technique: A Guide to Its Use. Available online: www.kepa.fi/tiedostot/most-significant-change-guide.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- El Chaarani, Hani, Prof Demetris Vrontis, Sam El Nemar, and Zouhour El Abiad. 2021. The impact of strategic competitive innovation on the financial performance of SMEs during COVID-19 pandemic period. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 32: 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabeil, Noor Fzlinda, Khairul Hanim Pazim, and Juliana Langgat. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic crisis on micro-enterprises: Entrepreneurs’ perspective on business continuity and recovery strategy. Journal of Economics and Business 3: 837–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, Hala Yudha, and M. Fahmi Johan Syah. 2021. Keberhasilan Usaha Berbasis Ekonomi Kreatif (Studi Kasus Pada UMKM Usaha Batik Kunayah di Desa Babadan, Kecamatan Bayat, Kabupaten Klaten). Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- González-Bravo, Isabel, Santiago M. López, and Jesús M. Valdaliso. 2018. Coping with economic crisis: Cluster associations and firm performance in the Basque Country. In Agglomeration and Firm Performance. Cham: Springer, pp. 245–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hariyanto, Alka Maula, and Deddi Duto Hartanto. 2021. Program community engagement pengembangan motif Batik Lasem sebagai bentuk pemberdayaan masyarakat Kawasan Batik Lasem. Jurnal DKV Adiwarna 1: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat, Saiful, Margono Setiawan, Fatchur Rohman, and Ananda Sabil Hussein. 2022. Development of Quality Digital Innovation by Optimally Utilizing Company Resources to Increase Competitive Advantage and Business Performance. Administrative Sciences 12: 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Charles W. 1980. Turnaround strategies. The Journal of Business Strategy 1: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutami, Farah Amirah, Andi Sudiarso, and M. Kusumawan Herliansyah. 2021. Identifikasi waste pada proses produksi batik tulis menggunakan pendekatan lean manufacturing dengan metode value stream mapping (studi kasus: Batik tulis di Giriloyo). Prosiding Seminar Nasional Industri Kerajinan dan Batik 3: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Ministry of Industry. 2020. Dilanda Pandemi, Ekspor Batik Indonesia Mampu Tembus USD 21,5 Juta. Available online: https://www.kemenperin.go.id/artikel/22039/Dilanda-Pandemi,-Ekspor-Batik-Indonesia-Mampu-Tembus-USD-21,5-Juta#:~:text=Dilanda%20Pandemi%2C%20Ekspor%20Batik%20Indonesia%20Mampu%20Tembus%20USD%2021%2C5%20Juta,-Jumat%2C%202%20Oktober&text=Industri%20batik%20merupakan%20salah%20satu,dalam%20mendongkrak%20pertumbuhan%20ekonomi%20nasional (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Indonesian Ministry of Industry. 2021. Serap 200 Ribu Tenaga Kerja, Ekspor Industry Batik Tembus USD 533 Juta. Available online: https://kemenperin.go.id/artikel/22830/Serap-200-Ribu-Tenaga-Kerja,-Ekspor-Industri-Batik-Tembus-USD-533-Juta (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Irvan, Muchamad, Andita Miftakhul Ilmi, Rona Fitria Nada, Siti Lailatul Isnaini, and Syerly Afifatul Khorinah. 2020. Pembuatan Batik Shibori untuk meningkatkan kreativitas masyarakat pada masa pandemi COVID-19. Jurnal Graha Pengabdian 2: 223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Ariful, Ishraq Jerin, Nusrat Hafiz, Danjuma Tali Nimfa, and Sazali Abdul Wahab. 2021. Configuring a blueprint for Malaysian SMEs to survive through the COVID-19 crisis: The reinforcement of Quadruple Helix Innovation Model. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics 9: 32–81. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, Marijn, and Haiko Van der Voort. 2020. Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Information Management 55: 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergensen, Jill, José Guimón, and Rajneesh Narula. 2020. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 47: 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karima, Agnia Khulqi. 2021. Pengembangan Usaha Batik di Kampung Batik Laweyan Dalam Masa Pandemi COVID-19. Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Kartikasari, Maulida Dwi, Dien Noviany Rahmatika, Sumarno Sumarno, Makmur Sujarwo, Sri Murdiati, Endang Sulistyaningsih, and Ahmad Farihi. 2021. Inovasi produk batik sebagai upaya mewujudkan masyarakat yang sehat dan sejahtera di masa pandemi Covid19 di Kelurahan Bandung Tegal Selatan. Budimas: Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat 3: 227–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katare, Bhagyashree, Maria I. Marshall, and Corinne B. Valdivia. 2021. Bend or break? Small business survival and strategies during the COVID-19 shock. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 61: 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P. 2019. Bagaimana Fintech & Pinjaman P2P Mengemudi Pertumbuhan UKM di ASEAN. Available online: https://www.aseantoday.com/2019/07/how-fintech-p2p-lending-are-driving-sme-growth-in-asean/?lang=id (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Keogh-Brown, Marcus R., Henning Tarp Jensen, W. John Edmunds, and Richard D. Smith. 2020. The impact of COVID-19, associated behaviours and policies on the UK economy: A computable general equilibrium model. SSM-Population Health 12: 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, Sascha, Thomas Clauss, Matthias Breier, Johanna Gast, Alessandro Zardini, and Victor Tiberius. 2020. The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 26: 1067–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, Rizki, and Widasapta Sutapa. 2020. Pengembangan kerajinan berbasis limbah batik sebagai sumber penghasilan alternatif bagi masyarakat sekitar Sentra Industri Batik Trusmi Cirebon. Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat 1: 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Laorden, Nikko Longjas, Jon Marx Paredes Sarmiento, Glory Dee Antero Romo, Thaddeus Retuerto Acuña, and Imee Marie Añabesa Acopiado. 2022. Impact of supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic to micro, small and medium enterprises in Davao Region, Philippines. Journal of Asia Business Studies 16: 568–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasati, Maulida. 2021. Pelestarian budaya Batik Nusantara sebagai identitas kultural melalui pameran di Museum Batik Pekalongan pada masa COVID-19. Tornare: Journal of Sustainable and Research 3: 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Hoang Ba Huyen, Thi Loan Nguyen, Chi Thanh Ngo, Thi Bich Thu Pham, and Thi Binh Le. 2020. Policy related factors affecting the survival and development of SMEs in the context of Covid 19 pandemic. Management Science Letters 10: 3683–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukiarti, Ming Ming, and Agustina Widodo. 2021. Strategi promosi dalam pengembangan pariwisata oleh Yayasan Lasem Heritage pada masa pandemi COVID-19. Prosiding Penelitian Pendidikan dan Pengabdian 1: 142–54. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Maria I., and Holly L. Schrank. 2014. Small business disaster recovery: A research framework. Natural Hazards 72: 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiswo, Masiswo, and Rihastiwi Setiya Murti. 2021. Industri kerajinan batik dan hiasan produk wayang kulit pada masa epidemik Coronavirus (COVID-19) di Desa Wukirsari. SENADA (Seminar Nasional Manajemen, Desain Dan Aplikasi Bisnis Teknologi) 4: 324–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maulana, Yudha. 2021. Tolong! Pandemi Bikin Batik Indonesia Terancam Punah. Available online: https://finance.detik.com/industri/d-5525502/tolong-pandemi-bikin-batik-indonesia-terancam-punah (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- McKinsey. 2020. How COVID-19 Has Pushed Companies over the Technology Tipping Point–and Transformed Business Forever. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Muhtarom, Muhtarom, Sutrisno Sutrisno, Muhammad Saifuddin Zuhri, and Duwi Nuvitalia. 2021. Membangkitkan kewirausahaan di masa pandemi COVID-19 melalui keterampilan pembuatan motif batik dengan konsep Fraktal. Pelita: Jurnal Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat 1: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyana, Makruf Kausar, and S. T. Hafidh Munawir. 2021. Identifikasi dan Mitigasi Resiko pada Batik Laweyan Selama Pandemi COVID-19. Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Nayuni, Ayu Pingkan, and Bachtiar Dwi Kurniawan. 2020. Inovasi pemerintahan dan pelaku usaha Batik Jumputan dalam pengembangan industri kreatif di masa pandemi COVID-19 (studi kasus Kampung Tahunan Yogyakarta). Jurnal Pemerintahan dan Kebijakan (JPK) 1: 159–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021. The Digital Transformation of SMEs. Paris: OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panegak, Muhammad Sulthon, and Tri Cahyo Kusumandyoko. 2021. Perancangan video promosi Batik Desa Sendangduwur Kabupaten Lamongan. BARIK 2: 229–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pramukti, Linda Laras. 2021. Pengelolaan saluran distribusi Kelompok Usaha Bersama Batik Seruni pada masa pandemi COVID-19 di Putat Purwodadi. Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetiani, Titi Rahayu, and Catur Ragil Sutrisno. 2021. Re-formulation business strategy pada UMKM Industri Batik Pekalongan memasuki era new normal. Jurnal Ekonomi Dan Bisnis 24: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Prihartanto, Henry Dwi, Andi Sudiarso, and M. Kusumawan Herliansyah. 2021. Pendekatan lean manufacturing untuk mengurangi pemborosan pada proses produksi batik kayu. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Industri Kerajinan dan Batik 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Putri, Rizky Febriana, and S. M. Budiyanto. 2021. Pengelolaan Industri Batik Pring Sedapur Melalui Kelompok Usaha Bersama (Kube) Mukti Rahayu Di Kabupaten Magetan. Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Surakarta, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Qehaja, Albana Berisha. 2021. Response strategies for SMEs in the time of pandemic COVID-19. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación Social 4: 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Qisthani, Nabila Noor, and Syarif Hidayatuloh. 2021. Analisis risiko dampak wabah pandemi COVID-19 terhadap rantai pasok IKM Batik Keraton. Jurnal Teknik Industri 11: 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, Tety, Rahayu Lestari, Fisko Arya Kamandanu, and Dani Syahrobi. 2021. Edukasi pelaku UMKM Wisata Pantai Minang RUA sebagai upaya mewujudkan Sustainable Tourism. Jurnal Pengabdian Dharma Wacana 2: 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjaban, Radjaban, Septi Riana Dewi, and Rianto Rianto. 2021. Implementasi website untuk meningkatkan omset penjualan Batik Berkah Lestari. KACANEGARA Jurnal Pengabdian Pada Masyarakat 4: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Muhammad Sabbir, Fadi AbdelMuniem AbdelFattah, Surajit Bag, and Mohammad Osman Gani. 2022. Survival strategies of SMEs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Application of SEM and fsQCA. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 37: 1990–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Retnawati, Berta Bekti, Marlon Leong, and B. Irmawati. 2020. Kondisi eksisting usaha mikro dan kecil kerajinan bahan alam di kota Semarang dalam bertahan menghadapi krisis akibat pandemi. Fokus Ekonomi: Jurnal Ilmiah Ekonomi 15: 462–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riani, Lilia Pasca, and Muhammad Roestam Afandi. 2020. Forecasting demand produk batik di tengah pandemi COVID-19 studi pada Usaha Batik Fendy, Klaten. Jurnal Nusantara Aplikasi Manajemen Bisnis 5: 122–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosyada, Mohammad, and Anah Wigiawati. 2020. Strategi survival UMKM Batik Tulis Pekalongan di tengah pandemi COVID-19 (studi kasus pada “Batik Pesisir” Pekalongan). BANCO: Jurnal Manajemen dan Perbankan Syariah 2: 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Rosa Nindia. 2020. Dampak pandemi COVID-19 terhadap UMKM Batik di Kabupaten Sumenep. RISTANSI: Riset Akuntansi 1: 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, Joni, Euis Laela, Istihanah Nurul Eskani, and Novita Ekarini. 2020. Konseptual desain masker batik di era pandemi COVID-19. Prosiding Seminar Nasional Industri Kerajinan dan Batik 2: A09. [Google Scholar]

- Setyawan, Nanang Adie. 2021. The existence of Lasem Batik entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Admisi dan Bisnis 22: 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sholikhah, Imroatus, Rochmat aldy Purnomo, Sayid Abas, Asis Riat Winanto, and Choirul Hamidah. 2020. Industri kreatif pada Batik Tulis Tenun Gedog: Kondisi sosial-ekonomi pasca COVID-19. ISOQUANT: Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen dan Akuntansi 4: 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, Polin M., Christianto Roesli, and Amarena Nediari. 2021. Pemberdayaan komunitas Batik Bayat di Klaten-Jawa Tengah dalam kreativitas desain produk sebagai keberlanjutan batik di era pandemi COVID-19. SENADA: Semangat Nasional Dalam Mengabdi 1: 270–76. [Google Scholar]

- Suhaimi, Ahmad. 2020. Analisis manajemen resiko UMKM Batik Bangkalan Madura di tengah pandemi COVID-19. Jurnal Manajemen Risiko 1: 141–48. [Google Scholar]

- Supriyono, Edy, and Nurmadi Harsa Sumarta. 2020. Efektifitas kebijakan relaksasi kredit pada UMKM Batik terdampak COVID-19 di Kota Solo. Prosiding Seminar Nasional & Call for Paper STIE AAS 3: 312–27. [Google Scholar]

- Suprobowati, Dewi, Mulus Sugiharto, and Miskan Miskan. 2020. Pengembangan varian batik ikat celup Dusun Hendrosalam melalui olshop di era pandemic. Prosiding Konferensi Nasional Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat dan Corporate Social Responsibility (PKM-CSR) 3: 1–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Xiaoyan, Zhong Wu, and Feng Yang. 2022. Research on the relationship between digital transformation and performance of SMEs. Sustainability 14: 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triatmanto, Boge, Anwar Sanusi, and Aris Siswati. 2020. Pemanfaatan video tutorial Batik Seng melalui akses media sosial pada pelaksanaan kegiatan pemberdayaan kepada masyarakat di masa pandemi COVID-19. Seminar Nasional Sistem Informasi (SENASIF) 4: 2423–32. [Google Scholar]

- Umaami, Siti Kholifatul, and Sri Wulandari. 2020. Eksistensi Batik Tulis Ronggomukti Kabupaten Probolinggo di era pandemi COVID-19. Paper presented at International Conference on Art, Design, Education and Cultural Studies (ICADECS), Malang, Indonesia, 24 October. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2019. Indonesian Batik. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/indonesian-batik-00170 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Wardoyo, Sugeng, and Tri Wulandari. 2021. Kreativitas seni batik di Desa Wisata Jarum Kecamatan Bayat Klaten Jawa Tengah pada masa pandemi COVID-19. Corak: Jurnal Seni Kriya 10: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, Matthias, Sarah Stanske, and Marvin B. Lieberman. 2020. Strategic responses to crisis. Strategic Management Journal 41: V7–V18. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, Matthias. 2015. Path dependence and the stabilization of strategic premises: How the funeral industry buries itself. Business Research 8: 265–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, Nugroho Mardi, Karsam Karsam, Yuyun Widiastuti, and Siswadi Siswadi. 2020. Penciptaan keunggulan bersaing UKM Batik melalui penerapan teknologi pengering batik dan digital marketing. Prosiding Konferensi Nasional Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat dan Corporate Social Responsibility (PKM-CSR) 3: 970–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, Lizzie, and Matt Walpole. 2008. Measuring social impacts in conservation: Experience of using the most significant change method. Oryx 42: 529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2020. The Global Economic Outlook during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Changed World. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- World Bank. 2021a. World Development Indicators. Available online: http://wdi.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- World Bank. 2021b. Pandemic Preparedness and COVID-19 (Coronavirus). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pandemics (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Wulandari, Stya, Dedek Kusnadi, and Khairun Najib. 2021. Analisis Program Strategis Pemerintah Provinsi Jambi Dalam Melestarikan Warisan Budaya Kerajinan Batik Daerah Jambi (Dalam Masa Pandemi COVID-19). Doctoral dissertation, UIN Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin, Jambi, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Yu, and Maria Watson. 2019. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of planning Education and Research 39: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, Erlinda N., and Erni Ernawati. 2018. Productivity paradox? The impact of office redesign on employee productivity. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 67: 1918–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, Seyedeh Zahra. 2022. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) facing an evolving technological era: A systematic literature review on the adoption of technologies in SMEs. European Journal of Innovation Management 25: 735–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutshi, Ambika, John Mendy, Gagan Deep Sharma, Asha Thomas, and Tapan Sarker. 2021. From challenges to creativity: Enhancing SMEs’ resilience in the context of COVID-19. Sustainability 13: 6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).