Abstract

This explorative study aims to contribute to the debate about citizen involvement in (complex) medical and social issues. Our research goals are: (1) to explore the main opportunities, threats and challenges to co-producing healthcare in vulnerable communities from the perspective of professionals, co-producers (i.e., citizens with a volunteering role) and service users (i.e., patients); (2) to distil lessons for public managers concerning the main issues involved in designing co-production initiatives. We studied co-production initiatives in the Dutch city, The Hague. These initiatives were part of a broader, unique movement named ‘Healthy and Happy The Hague’, which aims to change the way healthcare/social services are provided. Two intertwined research projects combine insights from interviews, focus group meetings and observations. The first project analyzed a variety of existing co-production initiatives in several neighborhoods; the second project involved longitudinal participatory action research on what stakeholders require to engage in co-production. The two research projects showed similarities and differences in the observed opportunities/treats/challenges. The study found that empowering citizens in their role as co-producers requires major changes in the professionals’ outlook and supporting role in the communities. It illustrates the potential of synergizing insights from healthcare governance and public administration co-production literature to benefit co-production practice.

1. Introduction

Healthcare systems in welfare states are increasingly facing major challenges (WHO 2018). Technological innovations, an ageing population, staff shortages and rising expenditures all represent significant challenges for contemporary welfare states (Rostgaard et al. 2016). Moreover, important inequalities exist among populations in terms of life expectancy and number of healthy living years (OECD 2017), and medical and social problems are becoming increasingly complex, especially among populations with a low socio-economic status. These developments may in turn promote new health risks such as obesity and mental stress (OECD 2017). In the Netherlands, a low socio-economic status leads on average to 15 fewer healthy living years compared to those of people with a high socio-economic status (CBS 2019). These developments pose urgent questions to the healthcare sector: How can we ensure that healthcare services are accessible to everyone? How can the increasing demand for more personalized services be met?

Among the proposed solutions is the idea of engaging service users as partners in their own treatment (De Jong 2022; Dent and Pahor 2015). Another solution is to encourage other community members, such as neighbors or family members, who should be encouraged to take responsibility for the co-planning and co-delivery of healthcare services. Within public administration literature, this development is known as ‘co-production’, i.e., (groups of) individual citizens who contribute directly and actively to the work of a public organization and to public service delivery processes (Brandsen and Honingh 2016). Studies on co-production often focus on the healthcare sector (for recent examples, see Bovaird et al. (2021); Pestoff (2018, 2021); Dunston et al. (2009)).

Though the literature emphasizes the value for both the citizens and society (McMullin and Needham 2018; Osborne et al. 2016), it also shows that implementation of co-production can be challenging (Torfing et al. 2016). This holds true especially for the healthcare sector, as this sector is inherently characterized by power imbalances between professionals on the one hand and patients/citizens on the other hand (De Weger et al. 2018). These power imbalances are, to a large extent, caused by the specialized knowledge that is held by professionals and the high professionalization of the organizational structures and processes. Due to this, citizens often consider health organizations as being ‘inaccessible’ (De Weger 2022).

In short, we identify three ways in which the successful engagement of citizens in co-production is hindered. Firstly, at an individual level of the professionals involved, medical professionals may resist initiatives (Vennik et al. 2016), as they feel forced to the sideline (Loeffler 2021). Professionals dismiss and sometimes even undermine the input of engaged citizens, sometimes because they do not consider citizens as capable enough simply because of their illness (Lewis 2014). Secondly, at an individual level of the co-producers/service users, citizens perceive their input is not being heard, and they feel mistrusted by the medical professionals or consider themselves as not competent enough to participate. Consequently, vulnerable and marginalized people are often underrepresented (Brandsen 2021), resulting in ‘social inequities’ in engagement (Holley 2016; Lewis et al. 2019). Thirdly, at a system level, the altered role of the service user requires “a significant re-imagining of traditional health system and practice trajectories”, which is not easily achieved (Dunston et al. 2009, p. 41).

These barriers might hinder the development of new co-production initiatives and scaling up and sustaining existing initiatives over time. Overcoming the barriers requires a deeper understanding of the dynamics of co-production. Though current studies address relevant pieces of the puzzle (e.g., the professionals’ persistence, the engagement of vulnerable people, sustainability and the effects of co-production initiatives), we still lack other pieces of the puzzle, such as an effective design, what works under what kind of circumstances and an understanding of the complexity of (the shift towards) a stakeholder-centered approach in healthcare (Halsall et al. 2022). Additionally, little is known about the ways communities themselves want to be involved and how professionals and health organizations can overcome power imbalances and design co-production initiatives that enables and stimulates citizens to become involved (De Weger 2022).

This exploratory article aims to encourage debate about citizen involvement in (complex) medical and social issues. The research aim is twofold. Firstly, we aimed to gather empirical insights regarding the main opportunities, threats and challenges to co-production from the perspective of professionals, co-producers (i.e., citizens with a volunteering role) and service users (i.e., patients). Secondly, we aimed to distil lessons for public managers concerning the main issues involved when they are designing co-production initiatives. Throughout the article, we illustrate the potential of synergizing healthcare governance and public administration co-production literature to benefit co-production practice. While medical science is traditionally more concerned with the service users’ deficits, co-production literature emphasizes the citizens’ capabilities (Kretzmann and McKnight 1993).

We collected data within the Dutch city of The Hague, which is exemplary for having many cities in developed welfare states (see Section 3). Over two rounds of data collection, we held interviews with sixty-four respondents, organized into three focus group meetings and conducted observations. Before explaining the research methods in more detail in the Section 4, the next section discusses the study’s theoretical context. We conclude with a discussion of the research findings in terms of its theoretical implications and derive practical lessons.

2. Theory

From early 2020 onwards, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed considerable pressure on healthcare systems worldwide (Schmidt et al. 2022). However, the contemporary healthcare systems of welfare states were, for aforementioned reasons, the subject of policy interventions long before the pandemic. From the 1980s onwards, a number of governments introduced policies focused on improving efficiency, often by introducing market reforms and competition into health sectors (Peters 2010). New Public Management ideas transformed service users into customers who were given the opportunity to express their opinions and preferences through choices and exit options. Ultimately, these policy reforms produced mixed results and suggested a need for alternative approaches to enhancing the citizens’ voices and freedom of choice (McMullin and Needham 2018). This outcome thus compelled policy makers and health professionals to persist in the search for creative solutions (Pestoff 2021).

One alternative approach is to include patients as involved citizens rather than just as consumers of care. This altered citizen role can be viewed from the perspective of both medical science and public administration. The former one relates to healthcare governance, while the latter one concerns the idea of public service co-production. These perspectives differ in terms of their focus on disease and deficiencies versus a citizen’s capacity and capability to improve their personal well-being. Synergy between the two perspectives helps us to overcome the initial hurdles facing co-production, both those dividing public managers and professionals and those dividing professionals and citizens.

2.1. Healthcare Governance

The involvement of patients as citizens in the coordination of healthcare systems is, increasingly, receiving attention. This is mirrored in discussions within medical science concerning the limits of medical knowledge, especially the influence of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP). EBP has contributed to the dominant governing principles such as accountability, transparency, standardization and control (RVS 2017), reflecting the concepts of New Public Management. Alternative approaches within healthcare literature, including Shared Decision Making (SDM), are emerging. With support from a lead medical professional, within SDM, the patients are encouraged to consider various treatment options (Reerink et al. 2021, p. 3). A more far-reaching, holistic and influential approach is built upon the notion of positive health (Huber et al. 2011), which expands the patient’s perspective from solely a biomedical phenomenon to a broader perspective on health, as elaborated in six dimensions. This broader approach contributes to a person’s ability to deal with the physical, emotional and social challenges of life and to remain in charge of their own affairs whenever possible (Huber et al. 2011).

In this article, we take this positive health approach as our starting point, with a special focus on people with medical and social problems that face cumulative obstacles to achieving good health. In this group, the personal health status is associated with, among others, socio-economic status (e.g., level of education, income and unemployment), as well as the livability of a neighborhood (e.g., housing quality and reliable social ties). To solve their problems, these citizens need another approach that goes beyond a single medical practice (De Jong 2022; Pavolini and Spina 2015). This is, a ‘passive medical’ treatment will not suffice to solve the complex problems. In this sense, the idea of health and social service delivery through co-production appears to be promising.

2.2. Co-Production of Public Services

The literature on public administration co-production addresses how citizens can participate in the planning and delivery of public services; these services not only address the individual social, health and economic needs of the involved service users, but they also provide a “viable and effective contribution to society now and in the future” (Osborne et al. 2016, p. 645). Co-production focuses on “the growing organized involvement of citizens in the production of their own welfare services” (Brandsen and Pestoff 2006, p. 496). This involvement can be voluntary, but participation might also be obligatory (e.g., in return for unemployment benefits). In this scenario, (groups of) individual citizens contribute actively and directly to the work of a public organization, leading to strong partnerships between the citizens and professionals (Brandsen and Honingh 2016).

It should be emphasized that the term ‘professional’ is used loosely, and it includes ‘classic’ professionals who are defined by the special features of their job (Freidson 1994) (‘street-level professionals’), as well as managers, for example, managers responsible for service provision (Van Eijk et al. 2019). ‘Citizens’ refer to service users (who directly benefit from the public services produced and contribute their experience of daily life) and individual citizens or communities (who share a particular geographic location, identity or interest and volunteer in the service delivery process) (Loeffler and Martin 2016). As such, both the service users (patients) and the volunteering citizens are referred to as co-producers.

The positive effects of co-production are catalogued in the literature, and they include the better use of scarce resources, increased citizen self-resilience, improved well-being and a higher satisfaction with the services that are being delivered (Batalden et al. 2016; Farmer et al. 2018; Lindenmeier et al. 2021). Co-production is more likely to involve vulnerable citizens than traditional forms of participation are (Brandsen 2021), though co-production in areas at a socioeconomic disadvantage and with more ethnic diversity is more challenging (Bell et al. 2021; Cerdan Chiscano 2021; Letki and Steen 2021). By applying the citizens’ input in the service delivery process, the anticipated outcomes include a strengthening of democracy and an improvement of the health conditions (He and Ma 2021; Pestoff 2009).

However, the implementation of co-production might be challenging, as the public sector, in essence, is not properly designed, organized, incentivized or experienced enough to effectively make use of the potentially rich citizen contributions (Loeffler 2021). Furthermore, co-production introduces certain risks. Co-production challenges the position of the professional service provider, and as professional work might already be ‘hollowed out’ due to reorganization, restratification and relocation (Noordegraaf 2016), the professionals are sometimes skeptical about new arrangements for public involvement such as co-production (Florin and Dixon 2004; Mulvale et al. 2021). Paradoxically, a problem for the healthcare sector especially is that citizens who encounter ill-health are strongly motivated to improve their health through participation in the service delivery process, while they simultaneously experience greater barriers to participation, especially if they are members of a lower socio-economic group. This situation can further reinforce existing health inequalities in society (McMullin and Needham 2018). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic showed the dependence of governments on their citizens to co-produce health and social services, and there was an increase in volunteering efforts to support vulnerable citizens (Carlsen et al. 2021; Bertogg and Koos 2021; Devine et al. 2021; Mao et al. 2021; Steen and Brandsen 2020).

Further research is therefore needed to better understand the opportunities, threats and challenges faced when one is seeking to co-produce citizens’ health and well-being, especially in the case of citizens in the more vulnerable communities with complex (medical and social) problems.

3. Study Setting: The Hague Movement ‘Healthy and Happy The Hague’

The city of The Hague is a good representation of other big cities in (Western) welfare states, where the residents’ health and well-being is challenged by a variety of factors including air pollution, low-quality housing and poverty (Berti Suman 2020). In The Hague, 69% of the inhabitants perceive their own health as ‘good to excellent’ (GGD Haaglanden 2018). Nevertheless, there are also important health problems such as obesity (49% of the inhabitants), severe obesity (14%), moderate-to-severe loneliness (52%), chronic disease (38%), heavy-to-excessive alcohol consumption (25%) and those caused by insufficient housing quality (14%), for instance, due to mold (GGD Haaglanden 2018). However, these averages mask huge differences among the inhabitants. An example is that the percentage of inhabitants stating they are ‘happy with their life’ varies from 20% to 90% (GGD Haaglanden 2018). These differences in the citizens’ health and well-being are related to differences in the medical and social problems, and they often correlate with the neighborhood that the citizens live in. Despite various policy initiatives in recent decades, rather than declining, the number of health inequities between socio-economic groups have actually increased in some respects (Scientific Council for Government Policy 2019; RVS 2017).

To address these differences, a unique movement—which is named ‘Healthy and Happy The Hague’—commenced in 2018, changing the way in which healthcare and social services are provided. This initiative involves collaboration between a number of stakeholders including the municipality, the public health service (GGD), the university, health and social care organizations and insurers. The movement’s aim is to organize and deliver health services on a scale that meets the service users’ needs, focusing not only on physical health, but also on the emotional and social challenges. Depending on the situation, additional organizations besides healthcare organizations may be involved in issues such as housing, debt, education, etc. This dynamic approach aims to empower the service user and their social network, while improving resilience or one’s capacity to improve their personal well-being (Van Aalderen and Bussemaker 2020). This approach is in line with the concept of positive health discussed above, which aims to prevent diseases, improve the quality of life and improve the delivery of health services.

In this study, we address the challenges facing this alternative approach, including issues such as how citizens can be involved in their own health and well-being and in the development of their own neighborhood. We studied the co-productive initiatives and the role of the professionals, co-producers and service users involved.

4. Methods

This article presents the results of two intertwined research projects that collected data from the autumn of 2019 to the spring of 2020. The first project involved students of Public Administration from Leiden University and investigated how co-production contributes to the improvement of the citizens’ health and well-being in The Hague. The project also explored the main challenges facing the management of health services when one is designing co-production initiatives. We selected co-production initiatives in six neighborhoods (see Table 1): neighborhoods that included vulnerable communities characterized by a mix of complex problems (e.g., unemployment, high levels of debt and low levels of education), as well as one of the richer areas in the city. This diversity helped us to provide in-depth and diverse insights regarding potential opportunities, threats and challenges.

Table 1.

Overview of interviewees in the interview research in six neighborhoods.

Most of the selected initiatives were directed at the vulnerable elderly citizens, but other groups such as people with cardiovascular diseases or those in need of psychiatric care were also included. The latter group is rarely involved in co-production due to the complexity of disease and high vulnerability of the service users. The initiatives were diverse in nature, and they included sport activities organized for immigrant women, co-producers assisting professional staff by volunteering at a nursing home, co-producers delivering tailor-made day-care programs for immigrant elderly people suffering from mental illnesses (e.g., dementia) and a project in which informal caregivers were themselves supported to reduce the risk of illnesses such as burnout.

For each initiative, interviews were conducted with an involved professional, co-producer and service user in order to gather insights from diverse viewpoints. For each actor type, we developed a semi-structured interview guide, which was partly inspired by the measurement tool for positive health developed by the Institute for Positive Health (Huber et al. 2011). The students were allowed to add some questions specifically linked to the initiative under scrutiny. The students conducted 34 interviews, and all of the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data analysis involved filtering statements from the notes that are specifically about opportunities, threats and challenges, and comparing the main findings for each initiative.

The second project concerned the first phase of a longitudinal participatory action research (PAR) study in the neighborhood of Moerwijk, one of the most deprived neighborhoods in The Hague. The aims were to gain insights concerning citizens’ and professionals’ views on health and happiness, and through PAR, to develop initiatives aimed at improving or maintaining health and well-being. PAR aims to create positive change by allowing the citizens’ voices not only to be heard, but to also involve them (Abma et al. 2017; Eelderink et al. 2020). PAR differs from most other approaches to public health research because it is based on reflection, data collection and action that aims to improve health and reduce health inequities by involving people who, in turn, take action to improve their own health (Baum et al. 2006). This report presents the results of the data collection and reflection phases only, which occurred prior to the co-creation of the initiatives. Nevertheless, the study provides valuable insights into the opportunities, threats and challenges of co-production in Moerwijk.

Data were collected during interviews (15 interviews with citizens and 15 interviews with professionals), two focus groups meetings with citizens and professionals (n = 8 and n = 10) and one meeting with the board members and managers of health and social service organizations, insurers and the municipality (n = 50). Participants were selected via unplanned meetings with citizens (service users/co-producers) in the neighborhood, followed by the introduction of new participants via citizens or professionals. The interviews were semi-structured and based upon the positive health model and the aims of the ‘Healthy and Happy The Hague’ movement. Additional data were obtained via observations made while we engaged in eating meals with citizens in the neighborhood and during consultations, and while citizens were engaging in transect walks with us through the neighborhood and during church activities.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and all of the data were analyzed by axial coding and a reflective thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2019). For each meeting or interview, we established what the participants said about the current situation, their desired situation and their view of the personal and local assets. The emerging themes were described and visualized, and these visualizations were shared in participant focus group meetings, and a dialogue started between the participants. During these reflective cycles, the participants together determined which initiative they wished to explore, which action to follow and what they required in addition to their personal and local assets.

We present the main findings per research project below, first describing the interview research in six neighborhoods, followed by the Moerwijk PAR.

5. Results: Interview Research in Six Neighborhoods

From the interviews, we gathered the opportunities, threats and challenges facing co-production that apply to the various initiatives that were studied. These insights suggest factors such as increased burdens and cultural barriers, which are discussed below (the quotes have been translated into English).

5.1. Opportunities

A large group of professionals and co-producing respondents cited the substantial capacity and willingness amongst service users and other citizens as the main opportunity, a resource that professional caregivers could build upon. The main problem is that citizens need to know which initiatives they could potentially participate in. The co-producers also mentioned that professionals could do more to promote existing initiatives and empower citizens to take on a co-producing role.

Some professionals explicitly mentioned the added value of the co-producers’ efforts. This added value is threefold. Firstly, the co-producers reduce professional workloads by taking over simple activities such as cleaning, making coffee/tea and playing games with the elderly people. As a result, the professionals have more time available for intensive and complex care tasks. This relates to the complementary tasks as identified by Brandsen and Honingh (2016). Secondly, the co-producers form a crucial link between the professional, the service users and the local community. One professional, a social worker supporting/coordinating citizen initiatives (Interviewee 9) mentioned:

“The people in the neighborhood, the volunteers, are the eyes and ears of that neighborhood. They know exactly what happens in that neighborhood; things that I as a professional not living in the area do not. The volunteers are therefore an important link between professionals and locals.”

Thirdly, the professional caregivers saw improvements in the service users’ health and well-being due to the co-production initiatives. These included direct improvements, for instance, due to sport activities, but often the effects were more indirect, such as reduced loneliness and improved social cohesion in their neighborhood. Some service users, especially the elderly people, mentioned the high turnover of professional caregivers: today’s caregiver is not the same person who works tomorrow or the next day. Trusting a professional caregiver is difficult for many elderly people, and they often perceive the professional as having a poor understanding of their needs. A co-producing citizen is more likely to be seen as a constant factor and someone who can listen and help communicate the service users’ needs to professionals.

In this scenario, the co-producers can be considered as ‘boundary spanners’, a literature term designating someone who helps to develop collaborations across (organizational) boundaries (Van Meerkerk and Edelenbos 2018). As service users often experience help provision from a chain of stakeholders, including one or more professionals, volunteers, family members, friends and neighbors, a complex network evolves in which the service user loses an overview of who performs what activities and when. The study respondents indicated that it is crucial that someone maintains an overview and communicates this to the other actors.

5.2. Threats

Though co-producers are often seen as adding value, this is not always the case. In an initiative in the Schilderswijk neighborhood directed at elderly people with a migrant background and a mental illness, the professionals mentioned that their burden increased with the presence of co-producers. This was mainly because in this case the co-producers did not participate voluntarily, but rather in order to secure unemployment benefits. According to the professionals involved, the co-producers were poorly motivated and were often late, randomly failed to appear and often had their own problems. The professional, a formal caregiver coordinating the volunteers (Interviewee I15), explained:

“They have their own challenges, and then they also need our help. Sometimes I am happy when they don’t show up, because I (often) have to explain what they should do during the day. Seriously …”

In other initiatives, it was mentioned that professionals were less enthusiastic about co-producers from lower socio-economic groups, who they deemed to be less competent.

However, as in the case of the elderly people with a mental illness initiative, we saw that the co-producers’ motivation sometimes increases as their involvement in a co-production initiative progresses. A co-producer who volunteered for this initiative (Interviewee I14) stated that as a result of her involvement, she “feels better now and more independent”. Due to her involvement, she was able to practice her Dutch language skills and felt appreciated by the elderly people.

Another important threat is that the professionals involved in co-production may feel uncertain regarding their new role in health service provision or may not feel enabled to perform it. Indeed, some professionals even felt restricted by the health system more broadly. This issue was particularly well explained by a professional in the Transvaal neighborhood, a physiotherapist involved in sports aimed at migrant women (Interviewee I27). Health insurance funding depends on the number of service users that she has, and as such, this physiotherapist has limited freedom to participate in co-producing activities. Spending time co-producing activities would result in no service users and no funding. While this physiotherapist expressed a willingness to participate and is convinced of the added value, she could only do so to a limited extent due to her need to generate an income.

5.3. Challenges

Co-producing health services can be extremely challenging as it introduces considerable uncertainty to the service delivery process. Issues such as the number of citizens willing to co-produce, the kind of task they can perform and how to keep them motivated over time all need to be resolved. The sustainability of the initiatives may also be an issue. In our study, the respondents in Transvaal indicated that neighborhood initiatives suffer from a lack of continuity for multiple reasons, some of which may not even be known. We indeed observed that some co-production initiatives are run by a very small number of citizens, sometimes even only one person. What happens when this enthusiastic individual retires or drops out for some other reason?

Furthermore, it became clear that co-producing may also impose a burden on the co-producing citizens. This applies in particular to informal care givers. While these co-producers are highly motivated (not least because of personal (family) ties to the service user), caring for someone can place an enormous burden on the caregiver, potentially resulting in burnout. In the Regentessekwartier neighborhood, co-production was therefore initiated in which professional caregivers cared not only for the service user, but also for the informal caregiver. The idea behind this initiative is that you cannot just drop the responsibility for providing healthcare onto the shoulders of ordinary citizens without also providing them with some form of support or care.

This initiative illustrates that co-production is more than just an attempt to reduce healthcare expenditure. Indeed, co-production also involves costs, as previously recognized by authors such as Bovaird (2007). Developing structures that simultaneously support the co-producers without imposing additional tasks and burdens (e.g., training, caring for or supporting co-producers) on the professionals involved has also proven to be challenging. Health services that require greater professional expertise, such as psychiatric care, are more vulnerable to this issue, especially when more intensive professional guidance is needed.

Another important challenge relates to the cultural backgrounds of both the co-producers and service users, which is a barrier that may hinder communication between the professionals, service users and co-producers and complicate the building of trust. In the vulnerable neighborhoods that were studied, around 75% of the citizens have a migrant background, and over 100 different cultural backgrounds are represented. While on the one hand social ties within these groups are strong, on the other hand, connecting people from different cultural backgrounds is challenging. Moreover, the service users must often overcome a barrier before visiting a professional doctor: they feel that the mostly white, male doctors will not understand them, and they may also have difficulties communicating due to them having a limited command of the Dutch language. The Schilderswijk initiative, which focuses on elderly people with a mental illness, has successfully tackled this issue by recruiting professionals from the same migrant backgrounds, helping to reduce or remove communication barriers between the service users and co-producers.

The professionals in our study indicated that the empowerment of people with a migrant background and/or a lower socio-economic status is particularly difficult because many service users seem to have a passive outlook. One professional, a general practitioner (GP, Interviewee I19) stated:

“People come (to you) with particular problems and then expect that the GP will take on the problem, do something about it and provide an answer that immediately helps them. It is a passive way of looking at healthcare. You have a problem, you present it, someone else solves it and you go home satisfied.”

Professionals had a different attitude of the more developed neighborhoods: they believe that the service users are more active and more willing to take ownership of their own health problems, and they sometimes even discuss solutions proposed by the professional.

However, it should be noted that this does not immediately imply that co-production is easier to realize in more developed neighborhoods. In fact, these neighborhoods are characterized by high levels of individualization and a lack the strong ties that are observed among people with similar cultural backgrounds in vulnerable neighborhoods. In more developed neighborhoods, citizens (both in the roles of service user and co-producer) are less willing to co-produce as they are less easily convinced of the added value. They are inclined to believe that they can solve their own problems and that others can do so as well. The lack of social cohesion among citizens in these neighborhoods tends to hinder longer-term co-production initiatives.

6. Results: Participatory Action Research in the Moerwijk Neighborhood

The focus of the PAR in this neighborhood was not on existing co-producing activities or participating citizens per se, but on perspectives regarding co-production. In neighborhoods with complex problems, the first question that had to be answered encompasses the needs that co-production activities should meet, taking the views of both the professionals and citizens into consideration. The insights gathered in this PAR involve factors such as the influence of personal circumstances on health, the citizens’ resilience and ambitions and the challenges of working and surviving in the neighborhood.

6.1. Opportunities

Both the professionals and citizens felt that the main opportunities were the citizens’ resilience and survival skills, which together mean that citizens are experts in helping each other and share a determination to offer a better life to their children. As illustrated by the comment of one of the citizens interviewed:

“This neighborhood has enormous survival skills, use these”.(Interviewee 16)

Citizens facing problems often place minimal trust in professional caregivers and authorities. However, they can build trusting relationships with another expert citizen who lives in the neighborhood, represents a constant factor and communicates the citizens’ needs to the professionals.

These involved citizens can reach out to, make contact with and involve other citizens. In one recent initiative, the citizens started a civilian cooperative, and they now aim to gain funding and carry out neighborhood projects that will benefit Moerwijk and improve the economic circumstances of its citizens. This cooperative aims to engage citizens as family support social workers, to clean-up outdoor spaces in the neighborhood or as community developers.

Churches in Moerwijk also play an active role in providing help and spiritual care, especially during health and social services out-of-hours periods. Churches therefore represent a trusted partner in the neighborhood. All of these initiatives contribute to empowering citizens to take on a co-producing role, and citizens, in fact, often state that they would like to take the lead when it comes to the development of their own neighborhood and express a wish to become less dependent on the choices that policymakers and local government make for them. Taken together, our findings highlight a huge ambition and desire to work together with professionals and policymakers to make Moerwijk a more sustainable neighborhood for the next generation.

6.2. Threats

The current circumstances indicate that the citizens are struggling to make ends meet and are far more concerned about their neighborhood, poor housing and mold, as well as safety and nuisance neighbors than they are about their own health. Indeed, the citizens perceive these external or environmental issues as a more serious challenge to their own health than their own behavior. As one interviewed citizen stated:

“Protect my health? Instead of talking to me about whether or not I should smoke, protect me against unhealthiness in the environment!”.(Interviewee 2)

Due to low rents, the neighborhood attracts numerous asylum seekers, young single parents, as well as people with mental health problems and addiction issues. Many citizens may not have enough money to buy healthy food or may lack information concerning healthy food.

Poverty and debt creates feelings of hopelessness, fear and stress, increasing the addiction risk, the number of physical and mental health problems and crime. These complex problems often hinder or preclude mutual help among citizens, as so many are themselves struggling. Nonetheless, the citizens often know their neighbors and try to help each other, for instance, concerning meals. The citizens may try to build a life, but they will often lack the necessary skills. While various parties offer opportunities to develop skills or to do voluntary work in order to co-create, many citizens experience a lack of adequate support and become disenchanted.

In many cases, numerous organizations provide help and care that is focused on one specific problem, yet they are unaware of the efforts of other involved organizations. For instance, research has highlighted a lack of collaboration between health and social services, welfare and community services such as housing and those in the municipality. This finding underlines the frequent lack of co-production between professionals and organizations, leaving citizens to address the resulting problems. Due to short-term policies and funding, many initiatives and projects are relatively brief and last only a few years at best, which in turn leads to citizens having a poor overview of what is available in their neighborhood. Citizens are often sent ‘from pillar to post’ when they are seeking assistance, and they regularly feel that they did not obtain the help they needed. This is illustrated by the comments of one of the interviewed volunteers:

“How can it be that someone living here has had no gas, water and light for six months. How is that possible? Does nobody notice this? As collaborating organizations we should have noticed this, don’t we?”(Interviewee 22)

People who do manage to change their life for the better often leave Moerwijk. We calculated that over a five-year period, 50% of the inhabitants left Moerwijk, rising to 65% after 10 years. This results in a fresh influx of citizens, often bringing new problems with them. Many active citizens feel undervalued, and being unable to achieve real change in the neighborhood leads to feelings of frustration, burnout and sadness. People frequently mention that they struggle to gain funding when they are starting citizen-led projects in the neighborhood. They often feel they lack the necessary knowledge and skills or feel that they cannot speak or write correctly. When they do eventually manage to share their opinion, they commonly feel that their voice is not heard.

Working as a professional in Moerwijk is also a challenge. Due to the perpetual cycle of problems, street-level professionals feel unable to provide the necessary help, leading to burnout and compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue occurs when professionals develop declining empathetic ability due to repeated exposure to others’ suffering (Peters 2018). Indeed, many professionals spend less than two years in the neighborhood, resulting in a major discontinuity of staff and consequent problems with co-production.

6.3. Challenges

While groups of citizens in Moerwijk are involved in activities and volunteering in the neighborhood, many citizens do not participate and are not contacted by street-level professionals. Twenty-five percent of the inhabitants are aged 20 or younger and forty-five percent of them are between 20 and 45 years old. In this group, 45% of them are single or a single parent. Young families often live in challenging circumstances and struggle with parenting problems, relational problems and poverty. They struggle with healthy eating and providing their children with the necessities. Nevertheless, a wish to provide for their children creates an opportunity to engage in co-production activities in collaboration with street-level professionals.

Focus group meetings with citizens and street-level professionals revealed that both of the groups share the same dreams, and they agreed upon 25 solutions to improve the neighborhood. Both the citizens and the professionals picked four solutions to explore in more detail. These solutions will require a co-production effort between the organizations and citizens in order to work as a complete system and produce a path out that pulls the community out of the trap of poverty and hopelessness. The entire system focus is described by a volunteer who addresses the problem of loneliness:

“You can’t say “I’m going to tackle loneliness”; you have to tackle the entire system, otherwise you’ll never make a breakthrough.”(Interviewee 10)

7. Discussion

In complex neighborhood environments in The Hague, two intertwined studies explored the similarities and differences in perceived opportunities, threats and challenges. Firstly, in almost all of the neighborhoods many citizens are capable of providing co-productive efforts: many citizens are willing and able to invest effort in their own health and well-being, as well as in their neighborhood. This promising finding supports Brandsen’s (2021) optimism concerning the potential to involve vulnerable people. The value added by co-producing citizens differed in the two studies and among the neighborhoods. How citizens contribute to the regular service delivery process depends to a large extent on the specific characteristics of the initiative.

The second finding shared by the studies was the importance of building a trust relationship between the service user and the co-producer. Due the high turnover of professionals, building trusting relationships is difficult. This finding supports the theoretical claim that the creation of sustainable partnerships is an important condition for building trusting relationships (Tsai 2011). The co-producing citizen, however, is considered to be a constant factor and connects professionals, service users and the local community. By building trusting relationships and overcoming linguistic issues, these individuals can be considered as boundary spanners.

Though it was unexpected at first, a third finding was that despite the less enduring nature of professional–service user relationships, professionals function as linking pins that connect potential co-producers to concrete initiatives. Previous research (cf. Van Eijk 2018) has shown that when they are deciding whether or not to co-produce, the first factors that the citizens consider are the type and salience of existing initiatives. Our study illustrates the importance of the professionals’ roles in this issue. In general, and despite the fact that professionals are quite well trained in collaboration, collaboration with communities appears to be challenging. In this context, collaboration implies an openness to the citizens’ contributions and a constant vigilance against depriving the citizens of a sense of ownership. Professionals have to learn to view their contribution not as a leading resource, but as an additional community resource.

A fourth finding was that once they were engaged, the citizens emphasized both the motivating and hindering roles of the professionals. We know from the literature that professional and citizen efforts can be positively and reciprocally stimulating, resulting in increasing mutual investments in a collaboration (Van Eijk 2018). The present study contributes to this picture by illustrating that this otherwise positive relationship can be hindered by existing power inequalities and cultural differences. Professionals and citizens do not always understand each other (sometimes literally due to language barriers), therefore hindering a potential collaboration. This finding stresses the relevance of clear communication and expectation patterns and the need to overcome power imbalances (cf. Loeffler 2021; Sudhipongpracha 2018; De Weger 2022).

As not all citizens were considered to be equally motivated or capable, a fifth factor was related to professionals perceiving co-production as burdensome. Their decisions concerning participation and the sharing of information in co-producing activities depended in part on this perceived burden. This finding is in line with Baptista et al. (2020) who identified negative attitudes towards citizens’ participation as an important barrier. Additionally, the finding is in line with a report from Vennik et al. (2016), who stated that some professionals resist collaborations, especially those involving co-producers from lower socio-economic groups. Likewise, professionals who do not feel engaged with co-production may experience a collaboration as being burdensome and challenging. Nevertheless, one of the most important challenges is the empowerment of people from a migrant background, and because these citizens commonly feel that they lack the necessary knowledge and skills and may not speak or write adequately, they often self-exclude from potential co-productions. Consequently, these issues unintentionally reinforce the idea of these citizens as being less competent and/or less interested in making their voice heard (Vanleene et al. 2019).

Breaking this deadlock requires that professionals receive support in their new role in citizen engagement. However, a sixth finding was that professionals often experience a lack of time and resources (often related to payment systems) for the co-creation of solutions together with organizations and citizens. The resulting project discontinuity and high in- and outflow of professionals further contributes to this problem. This, in turn, imposes a burden on the co-producers, resulting in feelings of frustration regarding real change and leads to the drop out of both professionals and citizen co-producers.

A seventh issue was that new co-producing relationships demand a different mindset amongst the involved professionals. Professionals need to learn how to let citizens develop their own initiatives. Co-production requires that professionals leave their comfort zones, venture beyond their own boundaries and cultural/linguistic habits and search for opportunities rather than limitations. It could be that professionals participate in citizens’ initiatives, rather than vice versa, leading to a blurring of the (analytical) boundaries between professionals and co-producing citizens. When unpaid citizens perform important tasks, this has fundamental implications for the paid professional, for instance, in terms of a professional’s autonomy and authority (cf. Noordegraaf 2016; Loeffler 2021). Furthermore, it is open to question whether we can reasonably expect citizens to shoulder these tasks freely and in the absence of an established training program.

The final issue concerns differences among the neighborhoods that were studied. The main difference between the more developed (e.g., Benoordenhout) and more vulnerable (e.g., Schilderswijk and Moerwijk) neighborhoods included in this study was that in the former one, the resident’s mindsets were more individualized. It is often assumed that a lack of social cohesion is a pressing issue only in vulnerable neighborhoods, whereas the situation is in fact more nuanced. Residents in Benoordenhout do not feel mutually connected, and there is a strong belief among the residents that they can deal with their own problems, and thus, do not need support. In the vulnerable neighborhoods, many residents feel (strongly) connected to other people who share the same social background, and as they are used to helping each other, it may be easier to initiate co-production initiatives within these subgroups. The risk, however, is that initiatives are targeted solely at a particular subgroup, and as such, they do not connect other community members in the neighborhood. Intimacy among the members of a particular subgroup can even encourage distrust of people outside that network (Fledderus et al. 2014). Consequently, professionals need a better understanding of the cultural differences, behaviors and habits of the various subgroups present in a particular neighborhood.

8. Conclusions

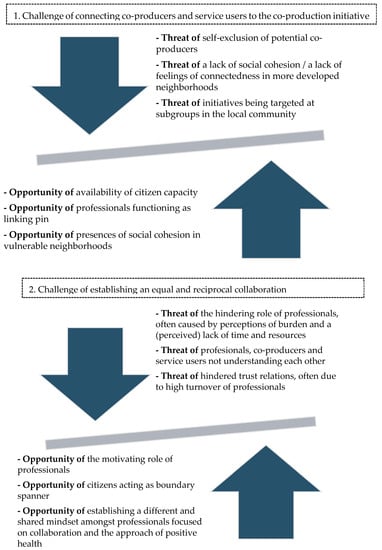

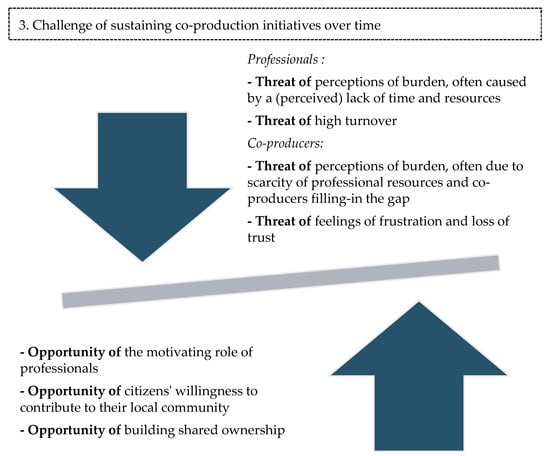

Focusing on complex neighborhood environments in The Hague, in this exploratory study, we empirically distilled insights regarding the main opportunities, threats and challenges to co-production from the perspective of professionals, co-producers and service users. The analysis of the empirical data yielded three main challenges, namely (1) how to connect citizens to co-production initiatives, (2) how to achieve an equal and reciprocal relationship or collaboration among professionals, co-producers and service users, and (3) how to sustain the initiatives over time. These challenges are enforced by or diminished by several opportunities and threats. In Figure 1, we visualize the different challenges, threats and opportunities. This model should not be considered to be a fixed theoretical model on how to design and implement co-production in vulnerable neighborhoods. Rather, the figure visualizes the main issues involved when one is designing and implementing co-production initiatives in vulnerable neighborhoods. As such, it helps to create awareness of the main opportunities, threats and challenges, and it can give guidance to the academic and societal debate on citizen involvement in (complex) medical and social issues.

Figure 1.

Visual overview of the main identified challenges, threats and opportunities for co-production in vulnerable neighborhoods.

In line with our research aim, our study offers several practical lessons:

- Co-producers can make valuable contributions to improving citizens’ health and well-being, but only under certain conditions such as when they are connecting (i.e., spanning boundaries) professionals to various organizations, service users and the local community;

- Citizens need to be reassured that their involvement is valued and receive sufficient support for these interactions;

- Professionals can help activate citizen involvement by asking the citizens to participate. Personal competencies and interpersonal skills play a crucial role here;

- Professionals require support from their organization in order to remain motivated over time and to enable their co-producing and boundary spanning role;

- Changes in organizational and management culture are required to help facilitate co-production initiatives and allow professionals to take risks when they are collaborating with citizens;

- To ensure that all of the co-producers can continue their efforts for longer periods (and thus, make co-production initiatives more sustainable), the management’s focus should extend beyond the health and circumstances of the professional (Bodenheimer and Sinsky 2014) to encompass co-producing citizens;

- A shared concept is needed to align collaboration and co-production and to inspire leadership. The promising concept in this regard is positive health, which is applied not only to citizens, but also to neighborhoods (Van Wietmarschen and Staps 2019), since it offers a tool to collectively change the living environment.

Sometimes citizens just need care, but when the citizens produce solutions for their neighborhood, public managers should focus on facilitating and supporting these citizens and street-level professionals in activities and policies for their neighborhood. A shared vision can align the policies, organizations and citizens and provide a coherent, integrated approach that supports the citizens in developing sustainable solutions and their co-producing role. This requires that public managers focus on dynamic interactions between professionals and diverse citizens, while creating conditions that favor innovation rather than control. Managers should therefore focus on enabling conditions that allow interactions to produce unexpected, emergent outcomes (Poutanen et al. 2016; Korlén et al. 2017).

Limitations and Further Research Suggestions

The study’s main limitations included the integration of the perspectives of service users without an active co-production role and the limited cultural diversity of the people that were interviewed. Some of the students interviewed were mainly native-born citizens, and the diversity of the cultural backgrounds interviewed during PAR in Moerwijk was also limited. Consequently, the study—and the distilled practical lessons—might reflect a bias on what less active service users and co-producers with a migrant background consider as the opportunities/threats/challenges of co-production. This limitation applies to co-production research more broadly; due mainly to linguistic issues, citizens from other backgrounds are less likely to participate not only in co-production initiatives, but also in research projects. We attempted to limit this bias as much as possible by consciously including the perspective of passive service users and by focusing on initiatives targeted at people with a migrant background. We now encourage other scholars to focus particularly on these underrepresented groups. To find more structural solutions for this problem, it is crucial to create diversity among the research community in itself and to train the researchers to be aware of their own biases.

Another recommendation for further research concerns the PAR research method. Based on our experiences, we believe that PAR is an effective tool in research and policy development, not only for the topic of health, but also regarding complex issues such as stress, loneliness and debts. The development of plans together with citizens requires that citizens are granted an equal position that exceeds their current role in community meetings or surveys, thus, the citizens’ knowledge needs to be taken seriously, and the citizens’ voices deserve to be heard and empowered (Abma et al. 2017).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V.E., W.V.d.V.-B. and J.B.; methodology, C.V.E., W.V.d.V.-B. and J.B.; validation, C.V.E. and W.V.d.V.-B.; formal analysis, C.V.E. and W.V.d.V.-B.; investigation, C.V.E., W.V.d.V.-B. and students Leiden University; data curation, C.V.E. and W.V.d.V.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.E., W.V.d.V.-B. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, C.V.E., W.V.d.V.-B. and J.B.; visualization, C.V.E.; supervision, J.B. for the overarching project and C.V.E. for the interview project conducted with the assistance of MA students at Leiden University; project administration, C.V.E. and W.V.d.V.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval for this study not applicable. At the time data collection was prepared and started (Summer 2019) the Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Leiden University holds no requirement to review and approve the project by an Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

None of the participating respondents in this study can be directly identified. Informed consent was obtained from part of the subjects involved in the study. For the interview research in six neighborhoods, the researchers informed contact persons in the neighborhoods (e.g., GPs) about the project and how the data would be used. The MA students further informed the participating respondents in the interviews. For the PAR research informed consent is harder to obtain, given the nature of the research method, but always obtained orally at the start of each interview and conversation. Here, the researcher participates in daily live activities and situations of respondents. For the focus groups and interviews respondents were informed about the research project, their role in the research and the use of data.

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying this study is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data underlying the interview research in six neighborhoods is stored at the Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University (confirm the data management policy). The data underlying the PAR research is stored at the SevenSenses Institute, Utrecht.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students of the course ‘Co-Production & Citizen Engagement’ (academic year 2019–2020) of the Master Program ‘Public Administration’, Leiden University for their assistance in collecting the data of one of the research projects underlying this study. They also would like to thank the large group of respondents for sharing their experiences and participation in both interview research and PAR. Furthermore: the authors would like to thank the reviewers for their feedback, as well as the organizers and participants of the Workshop on ‘Long-term Sustainability of Co-Creation and Co-production’ (Ghent, Belgium, 23–25 May 2022) for their feedback on an earlier draft of this article. This workshop was co-financed by the inGOV project, funded by the European Commission, within the H2020 Programme, under Grant Agreement 962563 (https://ingov-project.eu/) and the INTERLINK project, funded by the European Commission, within the H2020 Programme, under Grant Agreement 959201 (https://interlink-project.eu/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abma, Tineke A., Tina Cook, Margaretha Rämgård, Elisabeth Kleba, Janet Harris, and Nina Wallerstein. 2017. Social impact of participatory health research: Collaborative non-linear processes of knowledge mobilization. Educational Action Research 25: 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, Nuno, Helena Alves, and Nelson Matos. 2020. Public Sector Organizations and Cocreation with Citizens: A Literature Review on Benefits, Drivers, and Barriers. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing 3: 217–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalden, Maren, Paul Batalden, Peter Margolis, Michael Seid, Gail Armstrong, Lisa Opipari-Arrigan, and Hans Hartung. 2016. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Quality & Safety 25: 509–17. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Fran, Colin MacDougall, and Danielle Smith. 2006. Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60: 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, Ruth, Paul D. Mullins, Eleanor Herd, Katie Parnell, and Graham Stanley. 2021. Co-creating solutions to local mobility and transport challenges for the enhancement of health and wellbeing in an area of socioeconomic disadvantage. Journal of Transport & Health 21: 101046. [Google Scholar]

- Berti Suman, Anna. 2020. Multi-Stakeholder Cooperation for Safe and Healthy Urban Environments: The Case of Citizen Sensing. In Partnerships for Livable Cities. Edited by Cor Van Montfort and Ank Michels. London: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bertogg, Ariane, and Sebastian Koos. 2021. Socio-economic position and local solidarity in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of informal helping arrangements in Germany. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 74: 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, Thomas, and Christine Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine 12: 573–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, Tony. 2007. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services. Public Administration Review 67: 846–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, Tony, Elke Loeffler, Sophie Yates, Gregg Van Ryzin, and John Alford. 2021. International survey evidence on user and community co-delivery of prevention activities relevant to public services and outcomes. Public Management Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, Taco. 2021. Vulnerable Citizens: Will Co- production Make a Difference? In The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes. Edited by E. Loeffler and T. Bovaird. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 527–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brandsen, Taco, and Marlies Honingh. 2016. Distinguishing Different Types of Coproduction: A Conceptual Analysis Based on the Classical Definitions. Public Administration Review 76: 427–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, Taco, and Victor Pestoff. 2006. Co-production, the third sector and the delivery of public services. An introduction. Public Management Review 8: 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen, Hjalmar B., Jonas Toubøl, and Benedikte Brincker. 2021. On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: The impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support. European Societies 23 Suppl. 1: S122–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek). 2019. Statline. Gezonde Levensverwachting; Inkomensklasse. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/80298ned/table?dl=3A74F (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Cerdan Chiscano, Monica. 2021. Improving the design of urban transport experience with people with disabilities. Research in Transportation Business & Management 41: 100596. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Marja. 2022. Voorstad on the Move to Better Health. Evaluation of a Community Health Promotion Program in a Socioeconomically Deprived City District in The Netherlands. Ph.D. dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- De Weger, Esther. 2022. A Work in Progress: Successfully Engaging Communities for Health and Wellbeing. A Realist Evaluation. Ph.D. dissertation, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- De Weger, E., N. Van Vooren, K. G. Luijkx, C. A. Baan, and H. W. Drewes. 2018. Achieving successful community engagement: A rapid realist review. BMC Health Services Research 18: 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, Mike, and Majda Pahor. 2015. Patient involvement in Europe—A comparative framework. Journal of Health Organization and Management 29: 546–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, Daniel, Jennifer Gaskell, Will Jennings, and Gerry Stoker. 2021. Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature. Political Studies Review 19: 274–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunston, Roger, Alison Lee, David Boud, Pat Brodie, and Mary Chiarella. 2009. Co-Production and Health System Reform—From Re-Imagining To Re-Making. The Australian Journal of Public Administration 68: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelderink, Madelon, Joost Vervoort, and Frank van Laerhoven. 2020. Using participatory action research to operationalize critical systems thinking in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 25: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, Jane, Judy Taylor, Ellen Stewart, and Amanda Kenny. 2018. Citizen participation in health services co-production: A roadmap for navigating participation types and outcomes. Australian Journal of Primary Health 23: 509–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, Joost, Taco Brandsen, and Marlies Honingh. 2014. Restoring Trust Through the Co-Production of Public Services: A theoretical elaboration. Public Management Review 16: 424–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin, Dominique, and Jennifer Dixon. 2004. Public involvement in health care. BMJ 328: 159–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidson, Eliot. 1994. Professionalism Reborn: Theory, Prophecy, and Policy. Cambridge: Polity Pre. [Google Scholar]

- GGD Haaglanden. 2018. Stadsdeelprofielen. Available online: https://ggdhaaglanden.nl/ (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Halsall, Tanya, Kianna Mahmoud, Annie Pouliot, and Srividya N. Iyer. 2022. Building engagement to support adoption of community-based substance use prevention initiatives. BMC Public Health 22: 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Alex J., and Liang Ma. 2021. Citizen Participation, Perceived Public Service Performance, and Trust in Government: Evidence from Health Policy Reforms in Hong Kong. Public Performance & Management Review 44: 471–93. [Google Scholar]

- Holley, Kip. 2016. The Principles for Equitable and Inclusive Civic Engagement. A Guide to Transformative Change. Available online: https://ki-civic-engagement.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Huber, Machteld, André A. Knottnerus, Lawrence Green, Henriëtte van der Horst, Alejandro R. Jadad, Daan Kromhout, Brian Leonard, Kate Lorig, Maria Isabel Loureiro, Jos W. M. van der Meer, and et al. 2011. How should we define health? BMJ 343: d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korlén, Sara, Anna Essén, Peter Lindgren, Isis Amer-Wahlin, and Ulrica von Thiele Schwarz. 2017. Managerial strategies to make incentives meaningful and motivating. Journal of Health Organization and Management 31: 126–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzmann, John, and John McKnight. 1993. Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Towards Finding and Mobilising a Community’s Assets. Evanston: Institute for Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Letki, Natalia, and Trui Steen. 2021. Social-Psychological Context Moderates Incentives to Co-produce: Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey on Park Upkeep in an Urban Setting. Public Administration Review 81: 935–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Lydia. 2014. User Involvement in Mental Health Services: A Case of Power Over Discourse. Sociological Research Online 19: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Susan, Clare Bambra, and Amy Barnes. 2019. Reframing “participation” and “inclusion” in public health policy and practice to address health inequalities: Evidence from a major resident-led neighbourhood improvement initiative. Health and Social Care in the Community 27: 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmeier, Jorg, Ann-Kathrin Seemann, Oto Potluka, and Georg von Schnurbein. 2021. Co-production as a driver of client satisfaction with public service organizations: An analysis of German day-care centres. Public Management Review 23: 210–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, Elke. 2021. Co-delivering Public Services and Outcomes. In The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes. Edited by Elke Loeffler and Tony Bovaird. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler, Elke, and Steve Martin. 2016. Citizen Engagement. In Public Management and Governance. Edited by T. Bovaird and E. Loeffler. London: Routledge, pp. 301–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Guanian, Maria Fernandes-Jesus, Evangelos Ntontis, and John Drury. 2021. What have we learned about COVID-19 volunteering in the UK? A rapid review of the literature. BMC Public Health 21: 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullin, Caitlin, and Catherine Needham. 2018. Co-Production in Healthcare. In Co-Production and Co-Creation. Engaging Citizens in Public Services. Edited by Taco Brandsen, Trui Steen and Bram Verschuere. New York: Routledge, pp. 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvale, Gillian, Ashleigh Miatello, Jenn Green, Maxwell Tran, Christina Roussakis, and Alison Mulvale. 2021. A COMPASS for Navigating Relationships in Co-Production Processes Involving Vulnerable Populations. International Journal of Public Administration 44: 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordegraaf, Mirko. 2016. Reconfiguring Professional Work: Changing Forms of Professionalism in Public Services. Administration & Society 48: 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2017. Preventing Ageing Unequally. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, Stephen P., Zoe Radnor, and Kirsty Strokosch. 2016. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Management Review 18: 639–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavolini, Emmanuele, and Elena Spina. 2015. Users’ involvement in the Italian NHS: The role of associations and self-help groups. Journal of Health Organization and Management 29: 570–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, Victor A. 2009. A Democratic Architecture for the Welfare State. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, Victor A. 2018. Crucial Concepts for Understanding Co-Production in Third Sector Social Services and Health Care. In Co-Production and Public Service Management. Citizenship, Governance and Public Service Management. Edited by V. Pestoff. New York: Routledge, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, Victor A. 2021. Co-Production and Japanese Healthcare; Work Environment, Governance, Service Quality and Social Values. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B. Guy. 2010. Bureaucracy and Democracy. Public Organization Review 10: 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Emily. 2018. Compassion fatigue in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum 53: 466–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poutanen, Petro, Wael Soliman, and Pirjo Ståhle. 2016. The complexity of innovation: An assessment and review of the complexity perspective. European Journal of Innovation Management 19: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reerink, Antoinette, Jet Bussemaker, and Jan Kremer. 2021. Decision-making in complex healthcare situations: Shared understanding, experimenting, reflecting and learning. International Journal of Care Coordination 2021: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rostgaard, Tine, Fiona Aspinal, Jon Glasby, Hanne Tuntland, and Rudi Westendorp. 2016. Reablement: Supporting older people towards independence. Age and Ageing 45: 572–76. [Google Scholar]

- RVS (Raad voor Volksgezondheid and Samenleving). 2017. No Evidence without Context. About the Illusion of Evidence-Based Practice. The Hague: Council for Healthcare & Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Eduard, Jelmer Schalk, Marlieke Ridder, Susan van der Pas, Sandra Groeneveld, and Jet Bussemaker. 2022. Collaboration to combat COVID-19: Policy responses and best practices in local integrated care settings. Journal of Health Organization and Management 36: 577–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Council for Government Policy. 2019. From Disparity to Potential: A Realistic Perspective on Socio-Economic Health Inequalities. Policy Brief. The Hague: The Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, Trui, and Taco Brandsen. 2020. Coproduction during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Will It Last? Public Administration Review 80: 851–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhipongpracha, Tatchalerm. 2018. Exploring the effects of coproduction on citizen trust in government. A cross-national comparison of community-based diabetes prevention programmes in Thailand and the United States. Journal of Asian Public Policy 11: 350–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, Jacob, Eva Sørensen, and Asbjorn Røiseland. 2016. Transforming the Public Sector into an Arena for Co-Creation: Barriers, Drivers, Benefits, and Ways Forward. Administration and Society 51: 795–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Lily L. 2011. Friends or Foes? Nonstate Public Goods Providers and Local State Authorities in Nondemocratic and Transnational Systems. Studies in Comparative International Development 46: 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aalderen, Esther, and J. Bussemaker. 2020. Burgerparticipatie in (Gezond en Gelukkig) Den Haag. Epidemiologisch Bulletin 55: 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijk, Carola J. A. 2018. Helping Dutch neighborhood watch schemes to survive the rainy season: Studying mutual perceptions on citizens’ and professionals’ engagement in the co-production of community safety. Voluntas 29: 222–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, Carola J. A., Trui P. S. Steen, and Rene Torenvlied. 2019. Public Professionals’ Engagement in Coproduction: The Impact of the Work Environment on Elderly Care Managers’ Perceptions on Collaboration with Client Councils. The American Review of Public Administration 49: 733–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerkerk, Ingmar, and Jurian Edelenbos. 2018. Boundary Spanners in Public Management and Governance. An Interdisciplinary Assessment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wietmarschen, Herman, and J. J. M. Staps. 2019. Positieve Gezondheid de Wijk in! Handleiding Integrale Wijkaanpak op basis van Positieve Gezondheid en Leefomgeving. Bunnik: Louis Bolk Instituut. [Google Scholar]

- Vanleene, Daphne, Joris Voets, and Bram Verschuere. 2019. The co-production of public value in community development: Can street-level professionals make a difference? International Review of Administrative Sciences 86: 582–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennik, Femke D., Hester M. van de Bovenkamp, Kim Putters, and Kor J. Grit. 2016. Co-production in healthcare: Rhetoric and practice. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 150–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2018. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018—WHO Global Report. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).