Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

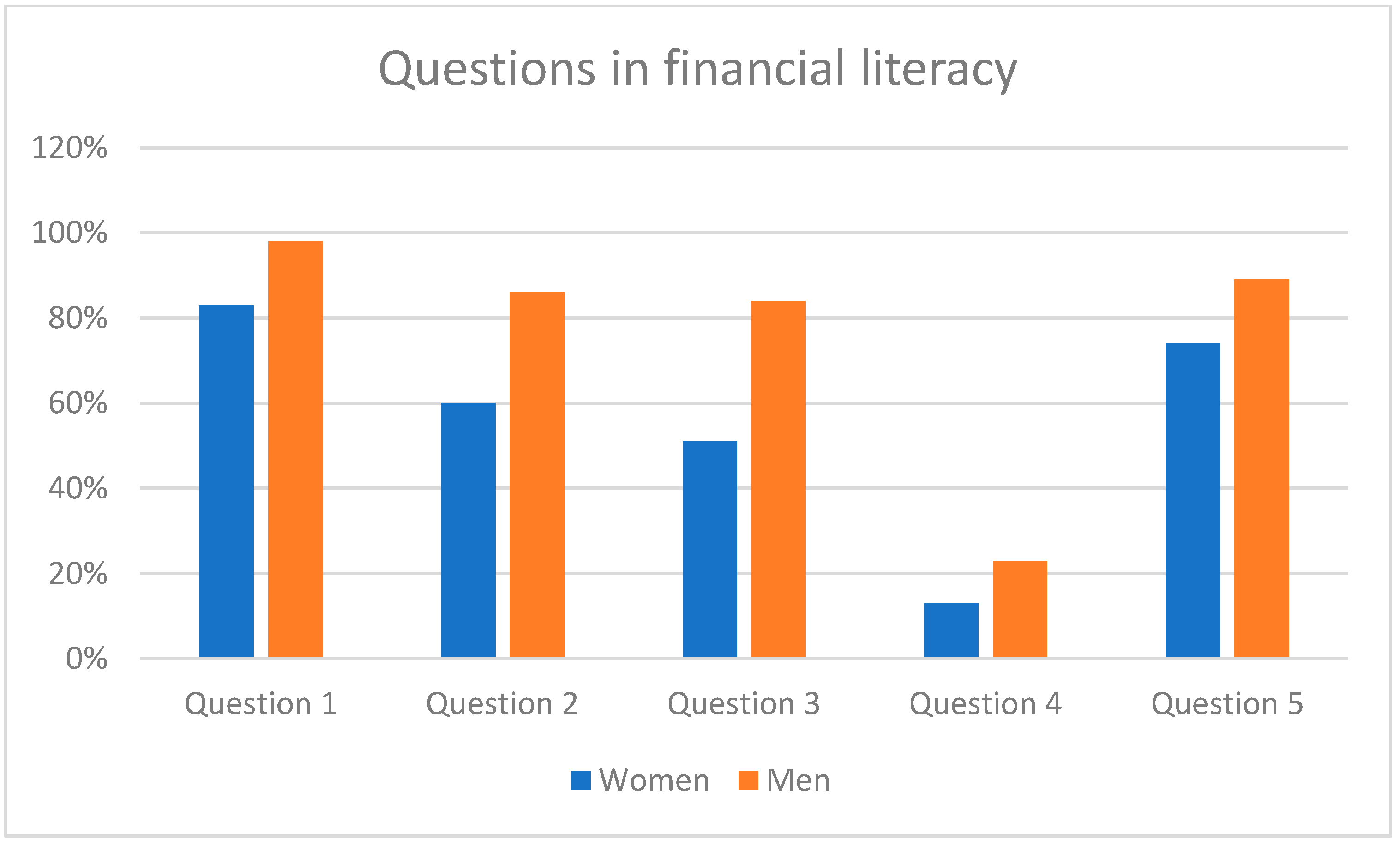

3. Results

4. Discussion and Implications for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, Sumit, Paige Marta Skiba, and Jeremy Tobacman. 2009. Payday Loans and Credit Cards: New Liquidity and Credit Scoring Puzzles? American Economic Review 99: 412–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, Sobhesh Kumar, Samir K. Barua, Joshy Jacob, and Jayanth R. Varma. 2015. Financial Literacy among Working Young in Urban India. World Development 67: 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano, and Nathan Nunn. 2013. On the origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128: 469–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, Sam, and William Walstad. 2011. The Effects of Perceived and Actual Financial Knowledge on Credit Card Behavior. Working Paper 2011-WP-15. Terre Haute: Networks Financial Institute at Indiana State University. [Google Scholar]

- Allgood, Sam, and William Walstad. 2013. Financial Literacy and Credit Card Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Analysis by Age. Numeracy 6: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenberg, Johan, and Anna Dreber. 2015. Gender, stock market participation and financial literacy. Economics Letters 137: 140–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Adele, and Flore-Anne Messy. 2012. Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network of Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bayar, Yılmaz, H. Funda Sezgin, Ömer Faruk Öztürk, and Mahmut Ünsal Şaşmaz. 2020. Financial Literacy and Financial Risk Tolerance of Individual Investors: Multinomial Logistic Regression Approach. SAGE Open 10: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, Elisabeth. 2013. Financial Literacy and Household Savings in Romania. Numeracy 6: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, B. Douglas, and Daniel M. Garrett. 2003. The Effects of Financial Education in the Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Households. Journal of Public Economics 87: 1487–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Marianne, and Adair Morse. 2011. Information Disclosure, Cognitive Biases, and Payday Borrowing. Journal of Finance 66: 1865–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Marianne, and Kevin F. Hallock. 2001. The Gender Gap in Top Corporate Jobs. ILR Review 55: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair-Loy, Mary, and Jerry A. Jacobs. 2003. Globalization, Work Hours, and the Care Deficit among Stockbrokers. Gender & Society 17: 230–49. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, Kimberly. 2012. The Rise of Financial Fraud. Center for Retirement Research Brief 12-5. Chestnut Hill: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Boggio, Cecilia, Elsa Fornero, Henriette M. Prast, and Jose Sanders. 2014. Seven Ways to Knit Your Portfolio: Is Investor Communication Neutral? CeRP Working Paper Series 140. Turin: Center for Research on Pensions and Welfare Policies, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bottazzi, Laura, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2021. Stereotypes in financial literacy: Evidence from PISA. Journal of Corporate Finance 71: 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher-Koenen, Tabea, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2011. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 565–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher-Koenen, Tabea, Annamaria Lusardi, Rob Alessie, and Maarten van Rooij. 2014. How Financially Literate are Women? An Overview and New Insights. NBER Working Paper No. 20793. Washington: Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC). [Google Scholar]

- Bumcrot, Christopher B., Judy Lin, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2013. The Geography of Financial Literacy. Numeracy 6: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, John Y. 2006. Household Finance. Journal of Finance 61: 1553–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Sewin, and Ann Huff Stevens. 2008. What You Don’t Know Can’t Help You: Pension Knowledge and Retirement Decision-Making. Review of Economics and Statistics 90: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Haiyang, and Ronald P. Volpe. 2002. Gender Differences in Personal Financial Literacy among College Students. Financial Services Review 11: 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Christelis, Dimitris, Tullio Jappelli, and Mario Padula. 2010. Cognitive Abilities and Portfolio Choice. European Economic Review 54: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., Jr., Antonio Terracciano, and Robert R. McCrae. 2001. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 322–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croson, Rachel, and Uri Gneezy. 2009. Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature 47: 448–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist. 2017. The Best and Worst Places to Be a Working Woman. The Economist, March 8. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Renee, Myria Watkins Allen, and Celia Ray Hayhoe. 2007. Financial attitudes and family communication about students’ finances: The role of sex differences. Communication Reports 20: 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FINRA Investor Education Foundation. 2006. Senior Investor Literacy and Fraud Susceptibility Survey: Key Findings. Washington: FINRA Investor Education Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, Raquel, Kathleen J. Mullen, Gema Zamarro, and Julie Zissimopoulos. 2012. What Explains the Gender Gap in Financial Literacy? The Role of Household Decision Making. The Journal of Consumer Affairs 46: 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornero, Elsa, and Chiara Monticone. 2011. Financial Literacy and Pension Plan Participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 547–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. 2017. Women, Peace and Security Index, 2017/2018. Washington: GIWPS and PRIO. [Google Scholar]

- Guðjónsson, Sigurður, Sigurbjorg Maren Jonsdottir, and Inga Minelgaitė. 2022. Knowing More Than Own Mother, Yet not Enough: Secondary School Students’ Experience of Financial Literacy Education. Pedagogika 145: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Justine, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Eric Chyn. 2011. Fees, Framing, and Financial Literacy in the Choice of Pension Manager. In Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, Ricardo, Laura D’Andrea Tyson, and Saadia Zahidi. 2011. The Global Gender Gap Report. Genea: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Jody, and Kimberly Merritt. 2020. Women in Finance: An Investigation of Factors Impacting Career Choice. West Palm Beach 20: 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, Bryce L., and Jyoti Savla. 2010. Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Family Relations 59: 465–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, Leora, and Georgios A. Panos. 2011. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning: The Russian Case. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippa, Richard A. 2010. Gender differences in personality and interests: When, where, and why? Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 1098–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippa, Richard A., and Joshua K. Dietz. 2000. The Relation of Gender, Personality, and Intelligence to Judges’ Accuracy in Judging Strangers’ Personality from Brief Video Segments. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 24: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippa, Richard. 1998. Gender-related individual differences and the structure of vocational interests: The importance of the people–things dimension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Carlo de Bassa Scheresberg. 2013. Financial Literacy and High-Cost Borrowing in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18969. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2008. Planning and Financial Literacy. How Do Women Fare? American Economic Review 98: 413–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011a. Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Well-Being. In Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Annamaria Lusardi. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011b. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 10: 509–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011c. Financial Literacy around the World: An Overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Vilsa Curto. 2014. Financial Sophistication in the Older Population. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 13: 347–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Vilsa Curto. 2019. Financial literacy amont the young. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 358–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria. 2012. Numeracy, Financial Literacy, and Financial Decision-Making. Numeracy 5: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, Janice Fanning. 2012. Performance-Support Bias and the Gender Pay Gap among Stockbrokers. Gender and Society 26: 488–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, Lewis. 2008. Financial Education in High School. In Overcoming the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Effectiveness of Financial Education and Saving Programs. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, John J., James P. Smith, and Robert Willis. 2009. Cognition and Economic Outcomes in the Health and Retirement Survey. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 15266. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Mottola, Gary R. 2013. In Our Best Interest: Women, Financial Literacy, and Credit Card Behavior. Numeracy 6: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, Michael D., and Jerome Rabow. 1999. Gender, socialization, and money. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29: 852–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, Gianni, Brenda J. Cude, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2013. Financial literacy: A comparative study across four countries. International Journal of Consumer Studies 37: 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsdottir, Katrin. 2018. Iceland is the best, but still not equal. Sökelys Pa Arbeidslivet Universitetsforlaget 35: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Melanie, and David Ansic. 1997. Gender differences in risk behaviour in financial decision-making: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology 18: 605–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargis, Madison, and Kathryn Wing. 2018. Female Fund Manager Performance: What Does Gender Have to Do With It?—Morningstar Blog. Morningstar, March 8. Available online: https://www.morningstar.com/blog/2018/03/08/female-fund-managers.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Schmitt, David P., Audrey E. Long, Allante McPhearson, Kirby O’Brien, Brooke Remmert, and Seema H. Shah. 2017. Personality and gender differences in global perspective. International Journal of Psychology 52 Suppl. 1: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, Soyeon, Bonnie L. Barber, Noel A. Card, Jing Jian Xiao, and Joyce Serido. 2010. Financial Socialization of First-Year College Students: The Roles of Parents, Work, and Education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39: 1457–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, Akio, Simon Baron-Cohen, Sally Wheelwright, Nigel Goldenfeld, Joe Delaney, Debra Fine, Richard Smith, and Leonora Weil. 2006. Development of short forms of the Empathy Quotient (EQ-Short) and the Systemizing Quotient (SQ-Short). Personality and Individual Differences 41: 929–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. 2020. Global Gender Gap (GGG) Report 2020. ISBN-13: 978-2-940631-03-2. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Yahya, Farzan, Ghulam Abbas, Ammar Ahmed, and Muhammad Sadiq Hashmi. 2020. Restrictive and Supportive Mechanisms for Female Directors’ Risk-Averse Behavior: Evidence from South Asian Health Care Industry. SAGE Open 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Kar-Ming, Alfred M. Wu, Wai-Sum Chan, and Kee-Lee Chou. 2015. Gender differences in Financial Literacy among Hong Kong Workers. Educational Gerontology 41: 315–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zissimopoulos, Julie M., Benjamin R. Karney, and Amy J. Rauer. 2015. Marriage and economic well being at older ages. Review of Economics of the Household 13: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Proportion | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 70.11% | 563 |

| Men | 29.14% | 234 |

| Other | 0.62% | 5 |

| Don’t want to say | 0.12% | 1 |

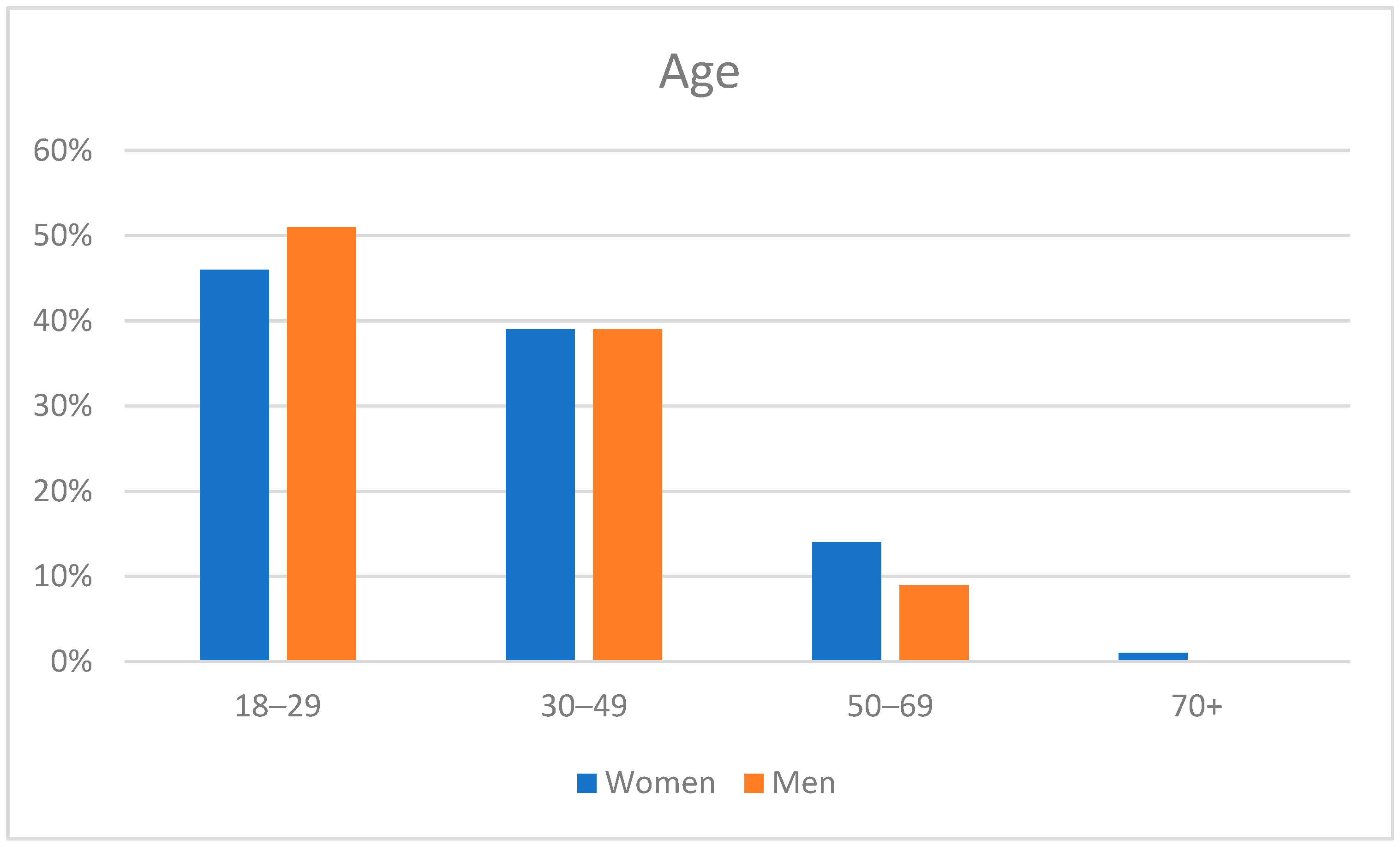

| Age | Proportion | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 18–19 | 47.32% | 379 |

| 30–49 | 39.32% | 314 |

| 50–69 | 12.73% | 102 |

| 70+ | 0.75% | 6 |

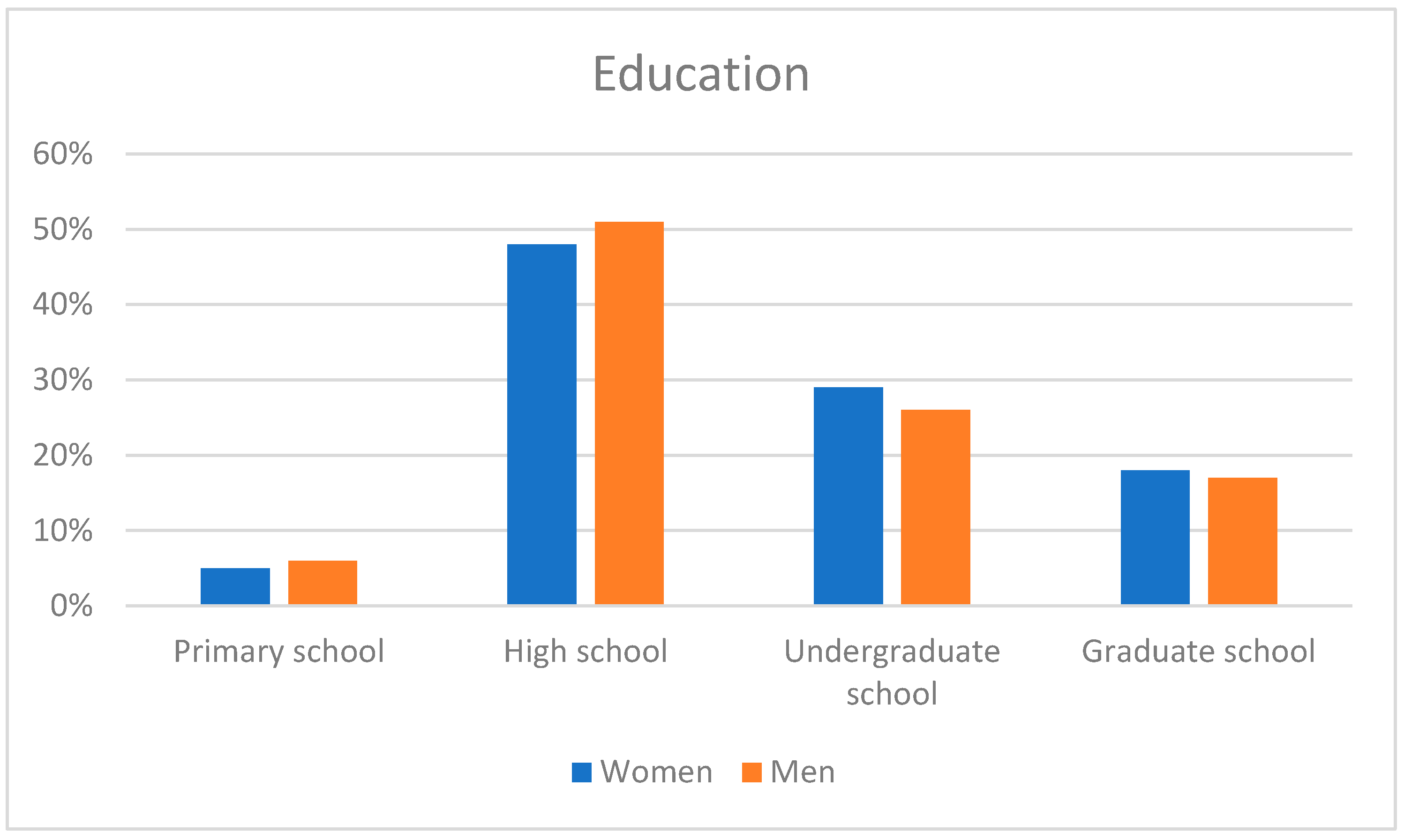

| Highest Education | Proportion | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Primary School | 5.24% | 42 |

| Highschool | 49.25% | 395 |

| University (BA/BS) | 28.05% | 225 |

| University (Graduate) | 17.46% | 140 |

| Model | B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.364 | 0.067 | 5.442 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | −0.67 | 0.13 | −0.188 | −5.248 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.089 | 2.499 | 0.013 |

| Education | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.237 | 6.624 | <0.001 |

| PEOPLE | 0.029 | 0.016 | 0.063 | 1.800 | 0.072 |

| THINGS | 0.029 | 0.016 | 0.063 | 1.800 | 0.072 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gudjonsson, S.; Minelgaite, I.; Kristinsson, K.; Pálsdóttir, S. Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things? Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040179

Gudjonsson S, Minelgaite I, Kristinsson K, Pálsdóttir S. Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things? Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(4):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040179

Chicago/Turabian StyleGudjonsson, Sigurdur, Inga Minelgaite, Kari Kristinsson, and Sigrún Pálsdóttir. 2022. "Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things?" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 4: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040179

APA StyleGudjonsson, S., Minelgaite, I., Kristinsson, K., & Pálsdóttir, S. (2022). Financial Literacy and Gender Differences: Women Choose People While Men Choose Things? Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040179