1. Introduction

The concept of sustainability is complex due to its cross-disciplinary character, the emphasis it places on the impacts of management decisions, its multidimensionality, and the requirement to take future generations’ needs into account. Consequently, defining sustainability frequently necessitates a multidisciplinary approach (

De Matteis and Borgonovi 2021). It is not surprising that bringing the idea of sustainable development into municipalities’ strategies has become one of the most important policy challenges of this century. Indeed, the need to make sense of UN Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the city level and in an urban context, including how to put SDGs in practice strategically to boost urban development, has gained momentum (

Taajamaa et al. 2022).

More specifically, target 11.6 of SDG 11, “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”, requires that by 2030, the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities be reduced, including paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management. Target 12.5 of SDG 12, “Sustainable Production and Consumption”, states that by 2030, it is important to substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse. Municipalities play a prominent role in addressing and governing how municipal solid waste management service providers operate regarding quality and waste collection options in engaging citizens. Considering the target set at the UN level, this paper provides insight to scholars and local administrators on how to contribute to meeting SDG 11 and SDG 12 at the local level by providing potential impact on environmental issues of local political economy and environmental policies.

If the policy goal is to reduce the environmental impact by reducing the amount of waste and increasing the percentage of separated waste and valuing materials, a prominent lever for local administrators is tariff design to charge municipal solid waste management (MSW) service.

Modern MSW charging schemes can be aimed at outperforming traditional metrics, such as square meters of property, the number of residents, or the socioeconomic conditions of users (

Alzamora and Barros 2020;

Welivita et al. 2015). MSW charges can be designed to provide an economic stimulus to encourage users to improve separate collection and recycling.

Fixed and quantity-based fees are the two most common funding models for waste management. The first is frequently employed because it is simple to use and guarantees a steady flow of revenue generation, which is advantageous given that revenue management is essential for business sustainability. The second approach assumes that consumers are billed based on the amount and type of waste they produce (

Chu et al. 2019;

Elia et al. 2015;

Morlok et al. 2017).

Approaches to charging users are based on the quantity and quality of waste generated. Implementing such a pricing mechanism can lead to robust outcomes in waste management performance, increasing the amount of waste that is individually sorted and is an economic instrument for waste management that applies the polluter-pays principle (

Morlok et al. 2017). Many scholars indicate that unit pricing (UP) schemes correlate with environmental sustainability (

Chamizo-González et al. 2018). According to the European Environmental Agency, there is a positive correlation between the implementation of these mechanisms and recycling rates.

Modern waste management charging approaches apply the polluter-pays principle by charging users according to the amount of residual, organic, and bulky waste they send for treatment and disposal (

Morlok et al. 2017). The UP concept makes it possible to determine charges partially proportional to the actual use of the MSW management service. It is a way to reduce environmental and economic costs while simultaneously conforming to the polluter-pays principle because it increases user participation by rewarding the virtuous behavior of those who sort recyclable materials and reduce residual waste (

Lakhan 2015).

Scholars have identified positive externalities associated with UP schemes (

Drosi et al. 2020;

Slučiaková 2021), such as an increase in the percentage of separate waste collection, reduction of waste produced per capita, reduction of unsorted waste, and positive repercussions in terms of image and reputation. Therefore, effective MSW charging schemes may be valuable levers for applying the polluter pays principle. However, there are transition costs, operation management issues, and service organization challenges. However, although these schemes promote economic, social, and environmental sustainability, they may increase waste management complexity and require more regulation, user involvement, and economic and technical resource inputs (

Morlok et al. 2017).

Designing such MSW charging schemes is complex and can involve high implementation costs, including complex fee simulations, drafting economic plans, implementing systems for monitoring and controlling vehicles, organizing delivery and geolocation of materials, engineering collection, measuring delivery, and provisioning an adequate software system. Efficient pricing mechanisms can boost recovery and investment decisions given the need to upgrade and improve a circular economy (

Bohm et al. 2010;

Gullì and Zazzi 2011;

Pérez-López et al. 2016;

Sarra et al. 2017). It is also important to assess environmental performance in terms of the quality and the level of sorted waste, given that the evolution toward advanced fee structure mechanisms concurs with circular economy goals (

D’Onza et al. 2016;

Debnath and Bose 2014).

The design of effective waste management services and how to incentivize user engagement by providing insights into the costs of municipal waste services are discussed as to whether an UP increases the percentage of waste collection at the local level, reducing the cost and the amount of waste produced per capita. The impact of UP on environmental performance, defined as the share of sorted waste and total waste generated, was tested. Furthermore, the authors also measured economic performance by comparing the cost of waste management and examined how the charging schemes impact the costs of specific MSW management activities. The results confirmed the role of UP schemes in increasing environmental performance in terms of the percentage of sorted waste and per capita waste produced.

This article has policy implications; our results may serve decision-makers in regard to reorganizing the part of the municipal waste management chain following structural evolutions, the enhancement and development of technologies to increase the effectiveness of waste sorting and collection, the provision of economic, fiscal, and regulatory instruments, and support for waste prevention. The diffusion of UP schemes can substantially contribute to the achievement of the objectives given that they can boost the virtuous behavior of citizens and businesses, which contribute to the reduction of the residual fraction and the increase of the percentage of sorted waste. It is suggested that local administrators put data-driven policy targets into electoral programs that, once elected, fall into government programs. Since local government programs must be applied at an operational level by the competent municipal civil servants and codified into the single programming documents, civil servants apply such policy guidance, transferring the desiderata contracting waste management utilities.

The rest of the document is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a description of the methods used to run the analyses, data sources, sample definition and research questions.

Section 3 presents the main results that are discussed in

Section 4. Conclusions follow.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This study includes a dataset merging data from different domains since data from multiple sources were gathered. Referring to

Figure 1, the PER_QUANTITY dataset included waste management costs per quantity of waste processes. In contrast, the PER_CAPITA dataset contained the same information normalized per capita. The QUALITY dataset comprised quality and performance information on waste produced, including sorting rates. These three datasets were downloaded from the Italian Institute of Environmental Protection cadaster portal. The UNIT_PRICING dataset comprised information regarding municipalities where a UP scheme was in place; such information was retrieved from municipality websites and the Italian Institute on Environmental Protections. The GEOSPATIAL dataset incorporated information regarding geographic domains published by the Italian Statistical Institute. The ECO dataset contained public finance information accessible from open data published by the Italian Economic Ministry.

2.2. Population and Sample

After merging the datasets, 6192 observations remained that were referred to as municipalities. According to the European Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), these municipalities can be equated to local administrative units (LAUs). Data included in the MSW cadastral also referred to more municipalities, since the cadaster allows for aggregated data in some circumstances. The dataset was filtered, keeping only observations on municipality-level data (n = 4341).

Since administrative units of Italy are regions, provinces, and metropolitan areas, the authors were able to stratify the sample, and municipalities were assigned to Group 1 (standard fees) or Group 2 (UP scheme). The second stratification criterion was geographical representativity. Provinces were included in the study if the share of municipalities with an UP scheme in place was more than 10% of the total number of municipalities of the province or metropolitan area. As seen from

Figure 1, our final sample contained 1679 municipalities that, after controlling for outliers in three key variables, became 1636, of which 516 in 25 provinces (

Figure 2) had an UP scheme (NUTS3 areas). The analysis was conducted at the LAU level, and the sample inclusion criteria were built on LAU and NUTS 3.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics regarding the groups. UP schemes were in place in smaller, less densely populated municipalities. Both statistics related to public finance indicate that Group 2 municipalities are associated with higher income levels.

Figure 2 shows the geographical scope of this research. One should note that the scope of the sample significantly impacts the results due to structural exogenous factors that specifically impact the waste treatment capacity and treatment options that in turn reflect on both the quality and cost of waste management.

Table 1 reports key information on the sample and groups identified to run the analyses.

Table 1 reveals some useful insights into the groups; Group 1 is roughly double Group 2, and it seems that UP schemes were in place in smaller, less densely populated municipalities. Both statistics related to public finance indicate that Group 2 municipalities are associated with higher income for the municipality and citizens.

2.3. Research Questions

In order to provide insights into how to contribute to meeting SDG 11, Target 11.6 and SGD 12 Target 12.5, the following four RQs emerged, of which the first two were tied.

RQ1: Are UP schemes and the percentage of sorted waste collection linked? RQ2: Is there an impact on per capita waste generation? The purpose of RQ1 and RQ2 is to test whether local administrators may support their economic and environmental policy choices to comply with SDG 11 target 11.6 to reduce the environmental impact of cities, particularly by reducing the impact of MSW. The following hypotheses were developed:

Hypotheses 1 (H1). The environmental performance of Group 2 is higher than that of Group 1.

Hypotheses 2 (H2). Per capita waste generation is lower in Group 2.

RQ3: What is the impact of UP on the total cost of management? The purpose of this RQ is to shed more light on the ambiguous impact of the UP scheme on total MSW cost; the hypothesis was developed as follows: H3: the total cost of MSW management is lower in Group 2.

RQ4: How does unit pricing impact specific services and phases of waste management? The purpose of this RQ is to provide scholars and local administrators with insights for service provision organization. Indeed, the hypothesis was developed to check the specific parts of the chains affected by UP schemes: H4: UP schemes only affect specific municipal waste management service phases.

The authors tested the following hypotheses comparisons with Welch t tests and relied on group comparisons to run the analyses. This inferential statistical test determines whether there is a statistically significant difference between the means in the two groups. The null hypothesis for the independent t test is that the population means from the two unrelated groups are equal: H0: mean (group 1) = mean (group 2).

3. Results

Figure 3 reports how we should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses.

Group 2 is associated with higher environmental performance (+4%). Similar indications were found for per capita generation of MSW (–12 kg). Considering the cost of MSW management, our results show that Group 2’s average cost per kg of waste is slightly lower than the average cost in Group 1 (–0.2 Eurocent/kg); however, the true means of Group 1 and Group 2 do not differ (

Table 2).

It was found that the environmental performance in terms of the share of sorted waste tends to be higher in Group 2. The environmental performance in terms of MSW generation tends to be lower in Group 2. When UP schemes are in place, the total cost of MSW management is lower. The average cost of MSW management did not differ significantly.

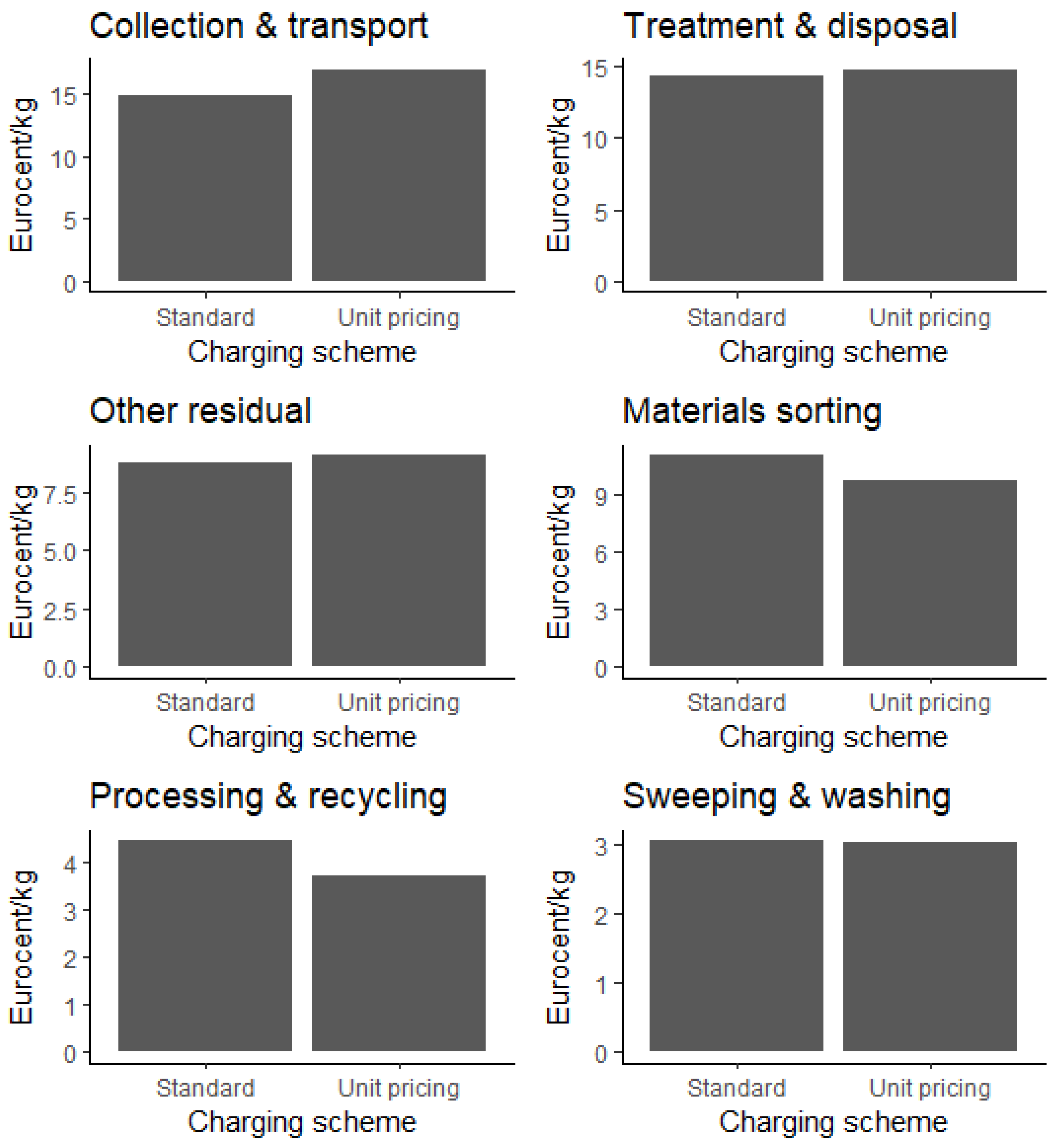

Figure 4 reports a breakdown of sub-costs of MSW management cost, comparing such sub-costs according to the charging schemes to test what sub-costs are affected most from different charging schemes.

As discussed in the Introduction,

Figure 4 shows that UP schemes affect only part of the costs of the service, given that some costs are not attributable to specific activities and are labeled common costs. From the results, the positive effects of UP schemes in three activities and the negative impact on the other three activities emerged. The cost of collection and transport increased from 14.9 to 16.9 Eurocent/kg with the UP scheme in place, the cost of treatment and disposal increased from 14.2 to 14.7 Eurocent/kg, and other costs of residual waste management increased from 8.74 to 9.11 Eurocent/kg. In contrast, the cost of materials sorting decreases from 11 to 9.65 Eurocent/kg, as the cost of processing and recycling decreases from 4.45 to 3.71 Eurocent/kg. The costs of sweeping and washing streets are almost unchanged, at approximately 3.05 Eurocent/kg in both groups.

Table 3 contains the results of the comparison among the sorted percentages of specific materials.

From the evidence provided in Table, it is possible to confirm the positive impacts of the UP scheme on organic, paper, and plastic materials but not for glass, wood, and weee materials.

4. Discussion

It can be confirmed that MSW charging schemes can be a valuable lever and an incentive for users to become involved in the circular economy transition. That said, no clear link with economic efficiency in terms of cost reduction emerged.

Although the results share some similarities with previous literature, there is little information regarding charging systems across countries (

Alzamora and Barros 2020). Considering the Italian landscape, a recent study emphasized that the MSW tariff system in use is deemed nonoptimal (

Drosi et al. 2020). Similarly, other scholars have suggested that UP schemes help reduce the amount of waste generated by 9.6%, albeit with a limited impact on the share of sorted waste (

Compagnoni 2020). In Belgium, scholars found that a UP system significantly increases the recycling rate to 71% and reduces the residual waste quantity, and the same study concluded that UP schemes could make an important contribution toward material reuse and recycling (

Morlok et al. 2017).

In Estonia, it was found that people are not economically motivated to sort their waste if the differences in fees between separately collected and unsorted waste are small, and implementing the UP system would increase the cost of waste management (

Voronova et al. 2013). Another study suggests that UP schemes may help curb the quantity of unsorted waste but do not increase recycling (

Huang et al. 2021).

In Sweden, an UP scheme was associated with 20% less waste per capita than other municipalities (

Dahlén and Lagerkvist 2010). The size of these effects has been found to depend on the pricing type (

Slučiaková 2021). Thus, it is fundamental for a pricing scheme to provide signals to users and encourage virtuous behavior, given that users generate costs when they produce waste and produce benefits when they adopt virtuous behavior (

Di Foggia and Beccarello 2021). This is particularly important to avoid strategic drifts of local administrators deriving from the fact that UP schemes lead to benefits in terms of cost reduction.

The policy implications of this article are important because they can support decisionmakers in a variety of fields. The main ones are the reorganization of the part of the municipal waste management chain based on the structural evolutions of the sector that the gradual increase of municipalities that are adopting UP schemes will speed up, the enhancement and development of technologies to increase the effectiveness of the collection of the main fractions, the provision of economic, fiscal and regulatory instruments, and support for waste prevention. The diffusion of SDG-compliant schemes can substantially contribute to the achievement of the objectives, given that they can be a valid aid to induce virtuous behavior in citizens and businesses, significantly contributing to the reduction of the residual fraction and the simultaneous increase in the percentage of differentiated waste, the optimization of collection logistics, and the reduction of the overall costs of the service. Nevertheless, it should be taken into consideration that policies adopted to improve the quality and performance of public services, including MSW, may need reforms at the governance level (

Beccarello and Di Foggia 2022) before being applied locally. Governance reforms should be coordinated at the supranational level to support the development of circular economy-related markets (

Avilés-Palacios and Rodríguez-Olalla 2021;

Di Foggia and Beccarello 2022;

Pires et al. 2011), which is necessary to accelerate the transition towards more sustainable economic systems.

5. Conclusions

The need to contribute to the understanding of how local administrations can contribute to meeting SDG 11, Target 11.6 and SGD 12 Target 12.5 has justified the questions proposed in this paper. With reference to RQ1 aimed at understanding if UP schemes boost the percentage of sorted waste collection linked and RQ2 designed to test if UP scheme reduce the per capita waste generation, from the results it is possible to state that the UP schemes studied here were associated with a higher percentage of sorted waste collection and less per capita waste generation so can be a valuable contribution to design economic and environmental policy targeted at SDG 11 target 11.6 and SDG 12 target 12.5 to reduce the environmental impact of cities, particularly by reducing the impact of MSW. Considering RQ3 on the impact of UP on the total cost of management, the impact of UP on the total cost of management was not clear, probably due to different impacts on specific services and phases of waste management. Similarly, from the analyses conducted to answer RQ4 on the impact of waste charging models on specific sub-costs, it was confirmed that it is useful to split the cost into its sub-costs to obtain more robust results. This is particularly important for a practical perspective, as this affects how the MSW management service shall be organized. In order to resume, we found positive effects of UP schemes on environmental performance, but a more detailed analysis is necessary to identify circumstances where the total cost of MSW management decreases because of UP schemes.

Our article has some limitations; the sample refers to a single year, it only includes approximately half of the municipalities that had UP schemes, the geographical scope of the analysis that significantly impacted the results, especially on costs, and the distribution of the analyzed variables was not normal. Other variables that impact waste management costs could be included in future studies, including assessing door-to-door collection approaches and examining the waste capacity mix at a regional level.

The results can benefit local administrators by showing how UP schemes may be beneficial based on the structure of their waste management costs and, consequently, how to intervene in designs that employ such cost structures. These findings inform decision-makers in different parts of the municipal waste management chain. UP schemes can contribute to a circular economy given that they induce virtuous behavior in citizens and businesses, reduce the residual fraction of waste, increase the percentage of differentiated waste, optimize collection, and reduce the overall costs of the service.

The paper therefore has policy and managerial implications as well. With respect to policy implications, local administrators shall insert data-driven policy targets into the electoral programs that they propose to citizens that one elected falls into government programs. This is followed by managerial implications since such local government programs must be applied at an operational level by the competent municipal civil servants and codified into the single programming documents. Finally, municipal civil servants apply such policy guidance, transferring the desiderata contracting waste management utilities according to the abovementioned SDG 11 and SDG 12 compliant decisions.