Abstract

The unprecedented nature and scale of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in mass lockdowns around the world, and millions of people were forced to work remotely for months, confined in their homes. Our study was aimed at understanding how pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements affected millennial workers in India. With signs of the pandemic slowing down, but with the likelihood of organizations retaining some of these work arrangements, the paper also explores how these are likely to affect the future of work, and the role that organizations and leaders have in managing the workforce in the ‘new normal’. The study follows an interpretivist paradigm and qualitative research approach using the narrative method as a key research strategy. The data was collected using in-depth interviews from Indian millennial respondents employed in both private and government sectors. The findings show a kind of work-life integration for the workers as a result of the pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements. This integration has been caused by four different types of issues that have also emerged as four major themes which have resulted in a further 10 sub-themes. The four major themes identified in this research are Managerial Issues, Work Issues, Logistical Issues, and Psychological Issues.

1. Introduction

The aftermath of the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worldwide (World Health Organization 2020b, 2020c) has disrupted billions of people’s lives (Garthwaite 2020). The initial responses of the majority of countries have been through the imposition of restrictions on international and domestic travel, lockdowns, and the closure of retail establishments and other services (Al Eid and Arnout 2020; Khalek and Eid 2020). The pandemic has caused enormous difficulties and miseries to millions across the world (Sengupta and Al-Khalifa 2022). This has subsequently affected industrial activity.

Millions of workers around the world have been forced to work remotely from their homes. The pandemic suddenly ushered them into emergent work practices, giving them little or no time to adjust from their normal work routines to a new work set-up (Choukir et al. 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic imposed certain emergent changes in the work practices that primarily include mandatory work from home (MWFH), virtual teams, online tech-enabled work platforms, and virtual leadership and management. Such sudden changes in work practices have been overwhelming for the workers, as well as the organizations and their leadership, who have been completely unprepared for the sudden changes (Andrade and Lousã 2021). This implied that workers and organizations improvised and adjusted to these arrangements that extended to days, weeks, and then months. This has affected both the lives and the work of the employees (Hoti et al. 2022).

This study was aimed at understanding how pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements have affected millennial workers in India. Moderating factors such as gender, sector of employment, and family status and structure have been chosen to show whether they are likely to decrease the effects of COVID-19. With signs of the pandemic slowing down, but likelihood of organizations retaining some of these work arrangements, the paper also explores how these are likely to affect the future of work, and the role that organizations and leaders have in managing the workforce in the ‘new normal’.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Origins and Developments

Studies of work practices, specifically working from home, have induced questions regarding the effectiveness of this mode (Bloom et al. 2013), as opposed to “on-site work”, whereby an employee is physically present in an office or work address. Questions of well-being (Golden and Wiens-Tuers 2008) and even the willingness to work from a remote location (Basta et al. 2009) have also been a subject of interest for researchers. The mandatory transition to working from home (due to disaster, pandemic, etc.), as opposed to the option of choosing this mode of work, is also an area of study (Thatcher and Zhu 2006). However, before delving into the findings of effectiveness, well-being, and the current situation of the pandemic, a look into the origins and developments of this practice is needed.

A 1991 study by the Division of Labor Force Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics in the United States, cited that from 20 million workers who worked from home, only 1.9 million, which account for less than 10 percent of the total, were paid for the work done at home, with the rest being voluntary work or self-employed (Deming 1994). A differentiation regarding profession also comes into play, with service-based occupations being the sector with the highest number of workers from home and “blue-collar” jobs accounting for less than 5.5% of the total (Deming 1994; Mateyka et al. 2012; Bloom and Van Reenen 2008).

2.2. Well-Being and Concentration

A study by Fonner and Stache (2012) in remote working emphasized the increased concentration levels expressed by employees who cited office distractions as a hindrance to on-site working, while Delanoeije et al. (2019) investigated the greater flexibility offered by this mode and how that contributed to increased rates of well-being. A decreasing work-home conflict was also investigated by Golden et al. (2006), with the merging of both spheres stated as being harmonious and reducing uncertainty.

Opposing the above studies, the negative effects of working from home, involving the same issue as above, have negative spillover effects with the “work on” mode at all times, which cause a tense home environment, and distractions from family members and household responsibilities cause inefficiency within at-home workers (Allen et al. 2015).

Feelings of isolation and anxiety have also been observed to increase with the at-home option, creating a remoteness that induces negative feelings, referred to as technostress by Suh and Lee (2017).

In a more positive way, some studies have investigated the urban pollution benefits of working from home, stating reduced vehicle pollution, less centralization, and lower emissions as being positive spillover effects of the work from home model (Bento et al. 2005).

2.3. Technology—A Means to Work

Studies on the emergent work practice of working remotely cannot be investigated without first considering the means by which such a practice is even a reality or an option. The developments of technology have allowed employees to conduct meetings from home, complete their tasks, and coordinate and perform required tasks. It allows the transgression of borders and connects in real time efficiency. Back in 1996, reflecting on the development of technology, the editor of the British medical journal, Richard Smith, estimated that a videoconference he had just conducted saved his company $8000 in travel expenses (Smith 1996). The accessibility that developments in technology allow us was also reflected by Smith as he pondered the transition to electronic documents, and how it revolutionizes education. He further expressed a tone of astonishment, mentioning a company in California where employees have never met each other physically (Smith 1996).

However, this does not come with unseen consequences, as the developments within the IT sector have created what Mazmanian et al. (2013) referred to as an “autonomy paradox”. It has offered independence regarding the option of mode of work; however, the continual connection and accessibility fosters pressure (Matusik and Mickel 2011), and studies conducted by Sonnentag et al. (2008) show that this leads to fatigue and dissatisfaction.

2.4. The Role of the Organization

The differentiation of whether the option to work remotely is forced upon an employee (whether due to a natural disaster, pandemic, or lack of access to the physical workplace), or when it is a voluntary option also plays a role and has been studied by Wiesenfeld et al. (2001), who mentioned that with the former, the organization will more likely provide support and guidelines.

Having the option of working from home as opposed to a mandatory rule on all employees to either work physically in the space or stay at home added a degree of suspicion and resentment among colleagues, whereby the at-home workers were regarded with suspicion regarding productivity by the on-site employees (Harris 2003). Employees working from home also expressed concern about promotion opportunities, and this was considered by Mokhtarian et al. (1998).

An organization must also consider the psychological effects of being away from the workplace, with studies investigating the isolating effect (Moingeon and Soenen 2004). This effect was further investigated by Thatcher and Zhu (2006), who studied the role remote working plays in identification with the firm, with results showing waning loyalty, as the remote worker will, according to Thatcher and Zhu (2006), no longer feel part of the organization. They have also found a contrast regarding identification with results when the option to work remotely was optional; employees still felt a sense of identification with the home organization; however, when it was mandatory, feelings of organizational identification were negative.

According to the World Health Organization (2020a), it is predicted that company employees’ managerial processes will continue to change, even after the current health pandemic is under control, in order to keep everyone safe. To date, employment norms and standards have changed and will continue to change due to the pandemic (Guzzo et al. 2021). Cirrincione et al. (2020) stated that, currently, employers are more lenient with their employees and are willing to accommodate different schedules and work situations, such as allowing parents to watch their children while working. These leniencies are expected to continue for the foreseeable future, and employers who want to gain a competitive advantage will likely be asked to make more accommodations for their workers’ needs and preferences.

According to Balicer et al. (2006), a study conducted by Johns Hopkins investigated the likelihood of employees returning to work after a pandemic and an estimated half of all healthcare employees did not plan on returning to work during an influenza pandemic that occurred in 2006 for the fear of contracting a communicable disease and increased burdens on workers, particularly female ones, at home during the pandemic. It is expected that more women than men will exit the workplace permanently due to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in developing nations (Azeez et al. 2021).

A report conducted by the Monthly Labor Review highlighted some of the major changes that have occurred regarding the recent pandemic. According to Dey et al. (2020), this survey explored the relationship between a worker’s ability to work remotely and actual incidents of workers working remotely. The study showed that an estimated 33% of all workers could theoretically do their job remotely. In the future, it is predicted that more people will have what is referred to as work-ready homes. These are areas of their home that essentially serve as an office and allow them to conduct their jobs remotely.

3. Context: India/Millennials

Millennials dominate the workforce around the world and especially in India. By 2028, roughly 75% of the global workforce will be comprised of millennials (Sengupta 2017). India currently has 426 million millennials, which is close to 36% of the total population, compared to 70 million in the US (21% of the total population) and 218 million in China (only 17% of the total population). India has not been untouched by the great resignation wave that started in US as the pandemic showed signs of slowdown. A recent report from Michael Page, a professional recruitment services firm, nearly 86% of India’s professionals will seek new jobs in the next six months as the Great Resignation in will intensify in 2022. Millennials have been at the forefront of this great resignation. The Great Resignation signals a breaking point in response to ongoing dissatisfaction, increasing distrust in business, and shocking events, such as the pandemic, that have made many reassess what is important to them’ (Deliotte 2022, p. 2).

Our study was aimed at understanding how pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements affected the millennial workers in India. With the likelihood of many of these work arrangements continuing in the future even as we return to normalcy, the findings are aimed at helping the organizational leaders to better manage the future of work.

4. Method

This study is a qualitative one using narrative research as an inquiry strategy. The qualitative research not only helps in focusing on the experiences and ideas of the participant but also makes it possible for the researcher to reveal detailed data in its natural setting. And since it is interpretative in nature, it provides an opportunity for the researcher to interpret the data (Cresswell 2003). Narrative research also provides an opportunity to gather data from real life and experiences. It helps in understanding “the outcomes of interpretation rather than by explanations” (Kramp 2004; Moen 2006). In this study, the narrative approach is highlighted based on how the pandemic-imposed work practices affected the work and lives of employees.

Narrative is regarded as “the primary scheme by which human existence is rendered meaningful” (Polkinghorne 1988). Hence, human experience is always narrated. Humans begin to understand love and feel sorrow or joy through the characters we encounter in novels or plays (Carter 1993). Narration of experience comes naturally, like learning a language. A child learns language by recounting his/her experience and telling short and long narratives (Gudmundsdottir 2001). Therefore, storytelling is a way of recounting and creating order from our experiences that begins in childhood and continues throughout our lives (Butt et al. 1992). The storytelling method was used to collect data that included the stories of thirty participants employed in various sectors in India. The stories are about millennial employees who have been affected by pandemic-imposed emergent work practices. Stories explain how pandemic-imposed work practices have affected their work and lives. In the study, the employees told their individual stories, which included their detailed experiences. In the analysis, the stories were re-read and reorganized regarding the objective of the research. In short, the participant stories were restored (Cresswell 2006).

4.1. The Narrative

Life is a complex set of experiences and dialogic interactions that people have with the world and with themselves, woven seamlessly but simultaneously overwhelming. Structuring these experiences into meaningful units can be a way to not only organize them, but also to draw meaningful knowledge from those experiences. One such unit is a story or a narrative. Narratives are all around us; we are creating them, and concurrently others are streaming their narratives to us. Writing narratives is a way of making sense of our experiences and the behavior of others (Zellermayer 1997). Each person has a narrative (Polkinghorne 1988), and researchers have even argued that life itself is a narrative that comprises many stories (Moen 2006). Therefore, narratives are seen as a way of understanding human experiences. When people tell stories, researchers collect these stories and write narratives to explain their experiences. Narrative is a method of structuring and organizing new experiences and knowledge by constructing knowledge so that it can easily be learned (Pachler and Daly 2009; Kramp 2004).

According to some studies, the narrative approach is a mode of inquiry and a research genre within the qualitative or interpretive research family (Connelly and Clandinin 1990; Gudmundsdottir 1997; Gudmundsdottir 2001). Others have argued that the narrative approach is not a method but rather a frame of reference in the research process, narratives acting as producers and spreaders of reality (Heikkinen 2002). Overall, it can be said that the narrative approach is both a phenomenon and a method (Connelly and Clandinin 1990). Narrative research is therefore the study of how human beings experience the world, and the narrative researcher collects these stories and documents narratives of these experiences (Gudmundsdottir 2001). What distinguishes narrative is not only its process and its features but also the mode of inquiry used for the purpose of study.

4.2. The Reason and Context for Using the Narrative Research Approach

Narratives have a sociocultural foundation. Social constructivism introduces us to various theories on human development and has several different versions. However, all versions have one thing in common: they all believe that human development happens through their participation in social activities. Both society (or the world) and the individual (or the mind) continuously influence each other, which helps humans learn and develop. Hence, in this manner, the dualism between the individual and his/her environment is eliminated. Sociocultural theory is one such version of social constructivism that connects the mind and the world (Prawat 1996).

Humans learn and develop in social and cultural shaped contexts. Thus, what people would become depends on what they experience in the social contexts that they participate. And the social contexts in which they participate depend on what they encounter at a particular point in time. The contexts keep changing as historical conditions also change. Therefore, human consciousness cannot be considered one being “fixed”; instead, it is continuously changing as the contexts keep altering (Vygotsky 1978).

The narrative research approach is within the framework of sociocultural theory, Vygotsky’s idea of the developmental approach in studying humans, and, finally, Bakhtin’s ideas of dialogue (Bakhtin 1986). The COVID-19 pandemic is a major unusual and unique context, a historical condition that is unparalleled in the last century of human existence in its enormity and effects on humans globally. Humans, in this context, much less by choice of their own, have been faced with sudden and dramatic changes both on their work fronts and regarding their own lives. How they exist and interact with society has all changed and is still changing. This explains our rationale for using a qualitative study using the narrative approach for this study. It helped us to understand what millennial workers in India experienced due to the pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements and the issues that affected them.

A thematic analysis was used alongside the narrative research approach (Braun and Clarke 2006) to crystalize the narratives into themes that the effects of the pandemic imposed with such things as remote work arrangements on the working and living of workers.

4.3. Participant Profiles

A total of 30 participants, all millennials, participated in this research while living in India. Participants were of both genders, working in the profit as well as the non-profit sectors, and private and government organizations.

The sample size was decided by following the principle of data saturation (Fusch and Ness 2015). An initial analysis sample of 25 was chosen, although saturation was only reached at the 17th interview. Beyond the 20th interview, the interviews did not yield any new data or themes. However, for the purposes of rigor, a ‘stopping criterion’ of five more interviews was added to the original 25, taking the total interviews conducted to 30 for this research (Hagaman and Wutich 2017).

The participants were aged between 26-years-old and 42-years-old. Among the participants there were fifteen women and fifteen men. The participants were single, married, with or without kids. They worked across various industries, both from the profit as well as non-profit sector, and from the private as well as the public sector (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Background Information.

The participants were identified through the professional networks of the researchers and their colleagues. The participation was completely voluntary, and all participants signed the voluntary consent form before being interviewed. Each participant shared their information and participated in a 40–60-min interview. All research ethics were followed in the entire research process to ensure participant confidentiality.

4.4. Data Collection Instrument

Semi-structured interviews were used to document the personal narratives of our participants. Considering that this study uses a narrative approach, and data was collected using semi-structured interviews, instead of a prepared interview script the participants were encouraged to share their stories regarding their experiences owing to pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements. The interview setting was arranged in a way to encourage free-flowing responses and thereby allow the participants to fully express their narratives.

The participants were encouraged to recount and record their stories regarding their experiences with pandemic-imposed work practices and how it has affected their work and lives. Since the study was conducted before the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing guidelines had to be followed in contacting the participants and collecting their stories. Hence, the participants were contacted electronically, and their stories were also collected electronically. The data was collected whereby the researchers and the research subjects worked in a collaborative dialogic relationship and the issue of the necessity of time and space to develop a caring situation in which both the researcher and the research subjects feel comfortable was ensured (Altork 1998; Connelly and Clandinin 1990; Heikkinen 2002; Kyratzis and Green 1997). A sense of non-judgmental attitude and a sense of equality were ensured while choosing the participants, and the researchers and the narrator had an intersubjective understanding of the narratives that occurred in the research process (Fetterman 1998). Since the researchers are also in the same context as this research, they interpreted the specific events in the same way as the research subjects narrated their experiences (Gudmundsdottir 2001).

The validity of the research was ensured as follows: Descript software was used to transcribe the recordings of the interview. After restoring the stories, they were taken back to the respective story owners to confirm the accuracy; peer debriefing was used to enhance the accuracy of account (Cresswell 2003); and actions and applications of the pandemic-imposed work practices were controlled and compared with the stories.

5. Findings

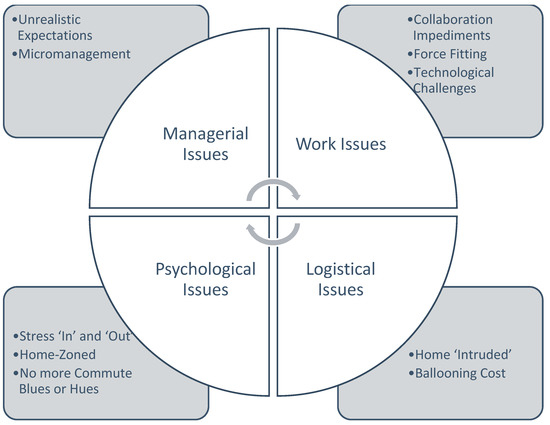

The findings show a kind of work-life integration for the workers as a result of the pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements. The thin line that existed between work and life has seemingly disappeared, with work becoming a synonym for life and life becoming a synonym for work, causing a kind of work-life integration. This paper presents the following structure: we identified four different types of issues faced by Indian millennials (due to pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements in our research) that have also emerged as four major themes, and that have further resulted in 10 sub-themes. The four major themes identified in this research are Managerial Issues, Work Issues, Logistical Issues and Psychological Issues.

5.1. Managerial Issues

5.1.1. Unrealistic Expectations

The onset of the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns induced sudden work from home for most of the people. Most industries and most jobs are not designed for work from home options yet, and hence this sudden switch caught the company and the employees unawares. All of a sudden the boundary between work and life started fading away. This has led to an increased workload and longer working hours.

“All meetings are now virtual; hence number of meetings have increased substantially. This is compounded when the number of stakeholders are more and spread across multiple time zones.”(P_2)

Being physically absent from work has fed into the idea that employees are available at all times. The set working hours have diminished giving rise to a perception that employees will be able to respond and attend meetings beyond the traditional hours.

“My manager expects me to respond to mails way outside the working hours, even at midnight. It is like a finger-on the-trigger situation for us. We have to be always ready, no matter if it is a holiday, weekend or late hours. Not that before pandemic we did not have this odd late hours or certain weekends when we had to work due to project pressures, but now all this has become a norm or you can say the new normal for us.”(P_4)

“My working hours are from morning 8 to evening 4. Being in teaching profession, these fixed working hours suited me very much since I have young children who need attention. Hence, this job allowed me to get back home in time to attend to my kids. But since we have gone online, we are expected to work beyond 4 pm, even so e official meetings stretch beyond the closing hours. And, of late, even some meetings are starting at 4:30 pm. It has become very difficult to manager work and home together.”(P_3)

The added stress and feeling of being constantly at work add to anxiety levels resulting in dissatisfied employees and therefore affecting productivity. A recent survey regarding the added stress levels found that 55% of respondents said it would help if their employer kept communication and work expectations within working hours. (Osborne 2021).

5.1.2. Micromanagement

Not being able to physically see the employees or have the accessibility to pass by their office has seemingly added to the stress of the managers to ensure that work is being done. Amongst the fear that employees might be slacking or not being responsible enough with their work encourages behaviours such as micromanaging. This not only causes psychological stress to employees, but it also hits at the well-being and productivity of the team.

“I suspect that some kind of surveillance software has been installed by the office It team during the recent round of updates. They are monitoring my screen time and the websites I visit. Just few days back I was watching a video on You Tube. This was not any kind of recreational video. I was actually watching a video related to latest technological aspects related to my job, during which I received a call from my manager asking me what I was doing. It felt like an interrogation call. Ever since that day, this has occurred two more time. During both these occasions I was either chatting with a colleague or taking a short break from work. This is really getting bothersome.”(P_17)

The pressure to pull through during bad times and the perception that work from home may mean employees will slack have at times resulted in unclear expectations from the organizational leaders, resulting in employee burnout and strong backlash.

“Leaders should learn to demarcate clearly between work and leisure hours. People might not speak openly for the fear of creating a negative impression about themselves, but prolonged exposure to such conditions will cause deterioration of health and motivation levels, resulting ultimately in reduced or average performance.”(P_8)

“My manager would send me mails late in the night, and by morning, by the time I logged-in I had a reminder in my inbox. This means that he was expecting me to respond to that mail in the middle of the night. That’s unacceptable. I do not feel I have a choice though…just have to pull-on somehow.”(P_22)

This was also addressed by Gary Stevens, an entrepreneur who stated that “Putting pressure on staff may sometimes have positive results, but, in most cases, you will probably find that the stress could cause productivity to slow down.” (O’Connell 2021).

5.2. Work Issues

5.2.1. Collaboration Impediments

A lack of personal touch due to being faces on screens or, even worse, just names, causes the absence of the personal rapport and collaboration which hits at productivity, a feeling of inclusion, and satisfaction in completing the job.

“I am in a new role, and it required meeting customers in the Asia Pacific region. It is almost a year, and I have not met any of them face to face. It is very difficult to build personal rapport by zoom or Teams meetings. For business, it is important to know each other personally, which you achieve through face-to-face meetings, dinners, and traveling together. I am missing that personal touch!”(P_10)

Like Umang, many have complained of the lack of “personal touch” owing to zero socialization and building of personal rapport.

“Working remotely does not feel same as working together in office. I have never done this in my life before. I usually reach office, collect my coffee and then on the way to my office, say a million ‘hellos’ and good mornings. That just gave a different vibe. I am missing all of that so much.”(P_12)

Every workplace and industry is not built to suit remote working. Those workers, experienced collaboration impediments partly because of their past habits and partly due to workplace design.

“I work in a different kind of set-up and getting team together physically, talking to them is important. This is not possible in remote settings. It is so much easier to just walk down to a colleague’s cubicle and discuss something related to the project. Now for doing this simple conversation, I have to send mails back and forth.”(P_7)

Research suggests many people feel the same way as in a survey by job searching site Indeed in 2021 found that 73% of people missed socializing in person and 46% missed work-related side conversations that happen in the office. They feel less part of a team and tend not to benefit from the advantages of being in a team such as sharing the work-load and increasing efficiency (Murray 2020).

5.2.2. Force Fitting

With no time to make this transition from the offline to online work model, industries that have never have or hardly ever experienced remote working have struggled. In the rush to continue business as usual during this crisis, the offline work models have been imposed in the online set-up. This has often resulted in the duplication of work and the redundancy of efforts.

“I am working as a professor in the higher education sector. The switch to remote has been sudden and we are using face-to-face learning designs in the online set-up. That’s not easy. Just take for example, every course that I teach has 4–5 assessments. Earlier these assessments would be either paper submissions or written exams. Now in the online system, all these assessments are based on online submissions. Students upload their work, that has to be then routed to the plagiarism software, downloaded, graded digitally and then uploaded back with feedback comments. An average of 45 students in the class means 90 downloads and uploads per assessment, or 450–500 downloads-uploads in a course. With an average of 5 courses for me in a semester I am faced with nearly 2000–2500 downloading-uploading work. This is just an example of how unproductive work has mounted on us. If we have to continue with the online or even hybrid, we will need to adopt digital learning designs and change our learning and assessment designs.”(P_21)

“We have to send a lot of offline videos as the number of periods are less compared to when proper school timings were there. Again, those offline videos have to be revised and taught in the online class if students have doubts regarding the topic, which generally happens. This results in doubling of the work.”(P_20)

“All our communications are now online. So, there is a lot of emailing, scanning work that takes a lion’s share of my work time. I wish we could use something like WhatsApp for our office communication and depend more on digitally signed documents, instead of printing, signing and scanning the documents in the archaic manner.”(P_1)

Almost all participants reported quantum leaps in the volume of work posts shifting to online mode.

This causes an overall gap in efficiency and has a direct hit on productivity timings. Staffing firm Robert Half concluded from a survey of 2000 plus workers that 45 percent of professionals have worked more hours from home than they would in a face-to-face setting. (Maurer 2021).

5.2.3. Technological Challenges

It was assumed that technology would be taken on instantly without having to guide those that might not be technologically aware of how to use these new applications. A feeling of being lost or not keeping up with the other colleagues will result in employees feeling a level of embarrassment and having to ask for help, and they might opt out of doing certain work, thereby hurting productivity. This has been referred to as technostress by Donati (Donati et al. 2021).

“I am learning new technology almost every other day. It is at time overwhelming and extremely challenging. But I guess, we need to do this to cope-up with the online work system and maintain similar levels of work efficiency.”(P_14)

“Earlier it was ‘learn to grow’, now it ‘learn to survive’. If we do not learn and learn fast, then we would simply lose our positions. Learning new technology, software is the mantra for survival. The younger blokes do better than us.”(P_9)

Clearly, the older millennial participants seemed to have faced this problem more than the younger millennials who are more comfortable with technology. Similarly, participants belonging to IT, advertising, and media coped with technology better and faster than those belonging to oil and gas, education, and other sectors.

“We are not IT professionals. I have been working in the oil and gas sector for more than a decade but have never seen so many changes in the way we work that we see during covid. The use of technology has increased manifold. Pre-covid one could ignore much of technology and still thrive in the industry. However, now one cannot! You have to learn; else you are out.”(P_6)

5.3. Logistical Issues

5.3.1. Home ‘Intruded’

The home was never designed to be an office, but now it is an office, school and also a place to stay. The sudden move into the home arena has also caused a strain and the home feels intruded upon. Everyone at home now needs a separate room or a working space, a laptop, and an internet connection. That is not easy considering most urban populations live in apartments, and an average person cannot afford a large one considering constraints on affordability.

“We are a total of five family members at home, with myself, my husband, my son, and in-laws. Considering that we live in a 2-BHK apartment, suddenly this space does not seem to be enough. I occupy one of the bedrooms for my work meetings; the other one (the bedroom of my in-laws) is occupied by my husband for his work. Being employed in the IT sector, he has many meetings to attend throughout the day. So, he needs a room for himself. My son attends his online classes in the living room. My in-laws who are old and need a place to rest have no choice but to remain seated quietly throughout the day in the living room.”(P_5)

“My office has provided me funds to purchase an office table and a chair, to set-up my office at home. But where is the space for the office. I should probably ask them to pay for a new house where I can plan a space for my office. I am actually converting my balcony in to my office. That’s the only spare space I got!”(P_23)

“Somehow in our home, the Wi-Fi works best in a particular corner. So both my husband and myself work from there. We have a table in that corner, and we put our laptops on that and work. I teach in a school, so I have my classes in the morning until 1 pm. My husband shifts his meetings post 1‘o’clock. That’s how we are managing. Thankfully my son is home-schooled, hence he does all his internet-based work in the evening.”(P_25)

“My husband and I both are techies, but I have always worked from home. Pre-covid I would see-off both my children to school and my husband by 7:30 in the morning and then peacefully I used to work. But with covid and everyone at home, it became chaotic. The younger child needs more attention, and he was finding it difficult to cope-up with online schooling more than my elder daughter. So, every now and then he c=would come running to the room where I would be working, and I had several embarrassing moments where he suddenly came when the camera was on, and I was in the midst of a meeting. On the top of that my husband’s voice is very loud, so even though he is working in the living room, I can hear everything he is talking in his meetings. That is so annoying!”(P_15)

The home is now under siege and managing space is a definite challenge.

5.3.2. Ballooning Cost

The pandemic has had a direct effect on the incomes of people and their future earning potential as well in most of the sectors. People have experienced salary cuts or cuts in important benefits, delaying the disbursement of salaries. Most participants reported setbacks to their incomes. This has been compounded with a rise in expenses.

“I have had three cuts in my salary since last six months. First the office announced a 25% cut, then it was increased to 35% and now it is 50%. On the other hand, the household expenses are rising. We are buying many stuffs like sanitizers, extra cleaning materials etc. that we were not buying before covid. It is quite a strain.”(P_24)

“I have bought 3 laptops since the COVID started. One each for my two children and another for my spouse. I also have to spend my broadband connection, as we need more bandwidth and speed with all of us working from home.”(P_19)

“I lost my job recently and that has hit our household income in a bug way. Thankfully, my wife’s job is still intact and that is why we are pulling-on with her salary and a bit of savings. Do not what will happen if she is also laid-off.”(P_13)

Expecting the transition to online work to be smooth as office space and professional settings attempt to be replicated caused employees to invest in personal items that resulted in a financial hit as well as not being able to accommodate these new demands into their current space.

5.4. Psychological Issues

5.4.1. Stress ‘In’ and ‘Out’

Dealing with bad news is never easy, and when there is a barrage of bad news, death statistics reported on a daily basis like a scorecard, the news of lockdowns and miseries of people pouring in, it becomes enormously difficult to deal with the same.

“I have shut down all my social media accounts. I just cannot deal with all the bad news coming across. And, then there is plethora of fake news spreading panic everywhere. I thought the best thing will be to close my social media accounts. At least that way I can stay away from these sites that are increasing my stress. But the television is still a problem. All sorts of disturbing images and bad news is played over again and again on all the channels. To add to this there is void cases and death counter running constantly on the corner of the screen. It feels like all this is going to get us someday.”(P_28)

The uncertainty level felt during the pandemic resulted in a feeling of uneasiness and placed the notion of venturing to work as taking a safety risk creating an atmosphere of uncertainty and anxiety. This causes employees to be on edge and to lose focus, and this affects their mental health. An article by Archbright, an American HR company, mentioned that the constant absence from work was being labeled as “job abandonment” and resulted in job loss during the pandemic (Sosa 2022). Having all these factors at play causes employees to live in a stress filled environment.

“For government essential services, many of the employees had no option of virtual work. Every morning they had to brave the corona scare to perform their duties. HR of many companies needs to retrospect their policies when it comes to employee health and safety.”(P_16)

In addition, those at home found an increase in home stress as well as work-related stress, compounding the situation and again affecting productivity and well-being.

“Because of longer hours, fatigue is higher as the screen time has increased substantially. The stress on the back and eyes is higher due to increased screen time. Also, working from home means one must balance between work and home, as kids and your partner are also working or attending school virtually.”(P_27)

5.4.2. Home-Zoned

A lack of face-to-face interaction due to staying within the house for prolonged periods of time causes feelings of isolation from the lack of social interaction. The main difference between normal times and pandemic imposed remote work has been workers missing face to face interactions with their colleagues (Toscano and Zappalà 2020). This negatively affects fulfillment, productivity, and inspiration.

“It is not the usual mornings these days. No good mornings, no greetings. I just switch on my laptop and start working. Throughout the day, many times, I feel that I am talking to my computer and not human beings. It is strange.”(P_30)

“Home at times feels like a prison. Last 15 days our building was declared as a mini-containment zone, since there were many covid cases reported. This meant that we were barred from going outside the building even to collect the groceries for which we have to go until the main gate of our apartment complex. Delivery boys are not allowed beyond that point. We literally had a fight with our building association as we were not able to even get our basic necessities. How can I focus on my work in this situation?”(P_11)

“My relationship with my spouse is strained. With both of us constantly together, and coping-up with the remote working pressures, household chores were the first flashpoint. This led to more and daily arguments. I think both of us need a bit of space, but this compulsion of being limited at home is doing us no good.”(P_13)

"The opportunity to chat, to joke, or to have spontaneous conversations had been squeezed out. Contact stopped altogether, shrinking my social circle at work. For those of us who are more extrovert, a lot was lost,” says Amanda Thomson, founder of her own beverage company. “I lost my inspiration”. (York 2022).

5.4.3. No more Commute Blues or Hues

The immediate notion of not having to commute to work might seem advantageous as the workplace is now a few steps away and no longer will people have to wait for trains, buses, or traffic. However, the spillover effect includes having to stay at the same setting all day as well as missing out on the social interactions that’s cause unseen fulfillment.

“I am happy that I can now use the 3 hours I use for commuting to and from the office for my family and myself. It saves a lot of energy and cost. Not to talk about the pollution that I can avoid as well. But I am also missing the socialization at office with my colleagues. Sometimes, I feel that commute with all its problems is better than being isolated at home.”(P_26)

“I travel every day in the metro train. The morning rush hours are not easy to negotiate. Most of times I do not get a seat even. But the conversations are very interesting with the co-passengers. There is some kind of entertainment on the train always. I have made some really good friends travelling on the metro.”(P_29)

“I love the fact that we are working remotely now. The best part is that I do not have to commute in the city anymore. The traffic is horrible, and we spend hours everyday commuting. Those hours we spend are completely unproductive and draining on energy.”(P_18)

“You can’t disentangle home and work anymore, and that’s not always easy,” says Jon Jachimowicz, an assistant professor in the Organizational Behavior Unit at Harvard Business School. Jachimowicz has been exploring the psychological notion between home and work, and according to research the commute offers a chance for “role-clarifying prospection”, while the current situation causes a blur delineation between ’home’ and ’work’ that is not desirable and results in frustrated employees (Fowler 2020).

6. Discussion

A sudden transition to working from home and other new work arrangements has caused many disruptions in the work and day to day life of workers, leaving most managers clueless about how to effectively manage workers in the new remote work arrangement. The findings of this study clearly show that pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements have caused a kind of work-life integration, resulting in conflicts in both work and life. Employees faced several issues, which could be segregated into four major types: managerial issues, work issues, logistical issues, and psychological issues (Figure 1). These issues spilled over into each other, resulting in a vicious cycle where one category of issues caused the other issues, and so on.

Figure 1.

Work-Life Integration and Conflict—Issues due to pandemic-imposed work arrangements.

The often unclear and unrealistic expectations on the part of the organization have meant a quantum leap in workload, with work hours and awake hours becoming synonyms of each other. The managerial myopia on how to manage employees during a pandemic has further compounded the situation, with most managers attaching unrealistic deadlines to tasks. Staying at home under the constant threat of pandemic, fear of a possible infection, and dealing with constant bad news has aggravated the stress and anxiety levels of employees. While the expenses of employees have increased during the pandemic, incomes have decreased—most industry sectors have seen pay cuts, zero pay hikes, job-cuts and/or the fear of job cuts. With most employees not used to working in virtual team arrangements, participants reported that they found it difficult to collaborate with their team members. Online digital work platforms have also created the challenge of coping with new technologies. Having an office at home and schooling of kids at home has also meant that the home space has shrunk, and participants with bigger family sizes have found it difficult to manage within the space available at home, often causing inconveniences.

Moderating factors such as age, gender, sector of employment, and family status and structure were chosen to show whether they are likely to disparate COVID-19 effects. Younger millennials found it relatively easier to cope with new technology demands because of pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements. Younger millennials took less time to learn and adjust to new technology, software, or online collaboration demands.

With everyone at home, the demands on the manager of the household have increased. In most cases, women assume this role (Titus et al. 2017), and their workloads have increased significantly, with men also sharing the load of the household chores in many cases.

The sector of employment only made a difference regarding coping with new technology. Employees in certain sectors such as information technology, the media, and advertising, where participants were more familiar with the use of technology compared to those from other sectors, found it slightly easier to cope with sudden demands to increase the usage of technology for work.

Finally, family status and structure had a direct relationship with the space availability at home for the new work and study arrangements. Families with higher incomes and larger apartments found it easier to allocate individual spaces to all members of the family for their work or study needs, while families living in smaller apartments faced a virtual shrinkage of space, offering less privacy to members for their online work.

Overall, the moderating variables of age, gender, sector of employment, and family status and structure did not considerably diminish the effects of COVID-19, except increasing the intensity of some.

The pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements have taught important lessons to organizations around the world. The myths around remote work arrangements have been shattered, and the digital revolution has been hastened, promising immense benefits both to businesses and to all stakeholders, including employees and customers (Ng et al. 2021). However, the unpreparedness for such a transition has exposed the problems that employees have experienced because of work-life integration. And with clear signs that the post-pandemic future of work may retain many of these work arrangements (Vyas 2022), organizational leaders need to respond by learning from their experiences during the pandemic. The future of work will need us to reinvent, reorient, and realign old rules, practices, and approaches. For many, WFH before the pandemic was a dream, and despite the early favorability of such pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements, there is a clear sign that glaring issues need to be resolved. Research shows that the current WFH lacks clear guidelines (Vyas and Butakhieo 2021).

The pandemic might have forever altered the way we live and work, and post-pandemic normalcy will not be similar to the pre-pandemic reality (Donthu and Gustafsson 2020). Work-life integration is a reality, and even after the pandemic is over, it may not go away. It is here to stay. Hence, adding to the challenge of managing and engaging a multi-generational workforce, organizations also have to tackle the challenge of the dissolving of work-life boundaries (Al Taji and Bengo 2018). Employees have also realized the benefits of such arrangements, avoiding long troublesome commutes to the office, being able to work for international employers without having to necessarily physically relocate, and being able to reduce their chances of infection and stay healthy.

Before the pandemic there was a sense of reluctance from the employers for WFH options because of the perceived lack of control over employees, fear of data privacy, in addition to the cost of such arrangements both in the short-term and long-term, in addition to effects on consumers and other stakeholders. However, the pandemic-imposed MWFH busted most of these myths, and now there is a strong likelihood that COVID-19 will accelerate the trend toward WFH past the immediate effects of the pandemic (Gartner 2020). In a recent global survey of professionals around the globe in the Learning and Development and Human Resources functions, 77% of respondents said that their organizations are now considering a permanent expansion of “work from home” flexibility for their employees (Simplilearn 2020).

A participant in this study (P_4), who works for an IT major, reported that his company was planning to continue with WFH for the majority of the workers even after the pandemic is over. Consequently, they are planning to reduce the office space drastically and to instead have more of a hub office that will allow them to control their operations virtually.

Consider the experience of one pharma company with more than 10,000 sales reps. In February, it switched from an offline model to a 100 percent remote-working one. As the containment phase of the crisis gradually recedes, you might expect remote work to fade as well. However, the company now plans to make a 30 percent-online–70 percent-offline working model permanent, thus leveraging the freshly developed skills of its sales reps.(McKinsey 2020)

The pandemic has made employers realize that they can trust employees in a remote working environment. Studies have shown that productivity actually increased during the pandemic in a MWFH setting (PwC 2021). COVID-19 has revolutionized the way companies and employees work, necessitating constant reinvention of how operations are carried-on and actions taken thereof to manage the same. This has generated significant changes in the workplace. Hence, the idea of the workplace will not be as it was before COVID-19. The reinvention of work, technology, and safety is key in this process of workplace transformation (de Lucas Ancillo et al. 2020).

Many studies have predicted the emergence of a hybrid work model post-pandemic for up to 60% of companies, while only 30% may opt for a pure back-to-office pre-pandemic model, and the remaining 10% may go fully remote (CNN 2021). A recent global survey by the BBC showed that most workers are not interested in returning to pre-pandemic work arrangements; instead, most would prefer a hybrid model (BBC 2020). While the degree of remote work may differ across industries and job types from those requiring greater physical proximity than others, there seems to be a general agreement that remote work and virtual meetings are likely to continue, although less intensely than at the pandemic’s peak (McKinsey 2021). In the future, workers may be categorized as fully remote, hybrid remote (work from office on certain days in a week), and on-site (not eligible for remote work). The PWC survey shows that there may be a transition in the real-estate strategy as companies anticipate multiple changes, with many companies consolidating office space in at least one premier business district location or opening more locations, such as satellite offices in suburbs or consolidating office space, but outside of major cities (PwC 2021). A recent global survey of professionals around the globe in the learning and development and human resources functions found that 77% of respondents indicated that their organizations are now considering permanent expansion of “work from home” flexibility for their employees (Simplilearn 2020).

Leaders must respond to shifting employee needs if they want to win in a post-pandemic world. Leaders need to exhibit greater levels of empathy. Research clearly indicates that a crisis such as a pandemic might bring about a change in leadership styles (Stoker et al. 2019), and organizations can expect themselves and their leaders to be prepared for the change only if they have invested in their professional development. To be effective and persuasive enough, leaders must (a) be able to state their values clearly, which will serve as a guide for institutional actions; (b) be able to comprehend the struggles and hopes of the organization; (c) be able to clearly communicate an ambitious vision that will guide the organization toward the same; and (d) exude and inspire confidence that strategic goals can be achieved (Antonakis et al. 2016; Grabo et al. 2017).

The online platform is here to stay; hence, processes need to be redesigned and new software needs to be developed to suit the changing demands of the online platform. Online work collaboration tools need to be deployed, and employees need to be given training in digital skills. Digital transformation is key to bridging employee skills gaps and building operating-model resilience in the post-pandemic world. Training will be needed for employees to gain critical digital and cognitive capabilities, social and emotional skills, and to develop adaptability and resilience (McKinsey 2020; PwC 2020).

The human resource policies for managing and strategies for engaging people also need to be reinvented. The future of work will have people working both in face-to-face and online settings, and policies need to evolve to manage and engage people both in place and space. The concept of a work time/hours, reporting/responding to emails/queries, the definition of mental health of employees and support that can be extended to deal with anxiety, guidelines to supervisors, and managers to manage their teams without causing stress, professional development in new emerging technologies, and most importantly, understanding generational needs in managing a multi-generational distributed workforce are some of the areas that need urgent attention. A PwC remote work survey published in January 2021 among U.S. workers shows a considerable gap in the perception of employers and employees regarding policies for managing people under MWFH during pandemics (Galanti et al. 2021). Executives surveyed expected policies to provide training for managers to lead teams in a remote environment, support employees’ mental health, provide mobile experiences for work applications and data, provide home office equipment, help employees manage their workload, set clear rules that establish the times when employees must be available, provide training for employees to work effectively in a remote environment, and to allowing flexibility in the work day so that employees can manage their family needs(PwC 2021).

In the post-pandemic world, as many of these emergent work arrangements are likely to continue, it will be important that leaders and HR heads redraft the HR policies to make them effective in the new “normal.” Research by Arora and Suri (2020) suggested a new model for HRD professionals to redefine, relook, redesign, and reincorporate the HRD interventions in the COVID-19 context that not only provides the basis for managing the COVID-19 pandemic aligned to organizational functioning but also how some leadership competencies can have a positive effect upon future actions. Another study offered an assessment of leadership competencies that are not only critical to respond to during times of crisis but that also reflect on the competencies needed after the crisis (Dirani et al. 2020).

7. Conclusions

The pandemic has caused a disruption in how, when and where employees work, and their adjustment to remote work depends on structural and contextual factors that are moderated by communication and communication technology use (van Zoonen et al. 2021). Our research helped us to understand the various issues (see Table 2) that millennial employees in India faced due to pandemic-imposed work arrangements.

Table 2.

Issues due to pandemic-imposed work arrangements.

Therefore, the contribution of our research is to bring forth how pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements affected the millennial workers in India. More importantly, considering that many of these remote work arrangements are here to stay, even after the pandemic, plus the fact that the millennial cohort will dominate the workforce in the coming years, means that the findings hold important lessons for organizations and leaders to effectively manage the future of work.

The position of companies and firms now is not where it was in 2020, as they are now equipped with the experience, research and trends. An organization that is able to take into consideration lessons learned from the pandemic and adjust current policies in this light will have an advantage and ensure continued, if not even greater, productivity. The most prominent fields to address are developing a suitable leadership style that can lead a hybrid workforce, a mandatory consideration of mental health of workers in light of the volatility and uncertainty in the context, redesigning processes to streamline them with hybrid work arrangements, removing inefficiencies and redundancy, increasing capacity building in digital skills for the future, creating mobile and online employee experience support for remote collaboration and engagement, and finally reworking and in many cases building for the first time a business continuity plan to face future pandemics or crises that can have a potentially disruptive effect on the operations and stakeholders.

The study has its own limitations. First this study is only based on millennials and hence the findings cannot be generalized for all sets of employees. However, considering that millennial workers constitute a majority of the workforce in India, this limitation is moderated to a large extent. Furthermore, this is a study on Indian millennials and hence cannot be generalized to other countries and regions.

Based on the literature and our observations, we feel that workers in other countries have also been similarly affected by the pandemic-imposed remote work arrangements. Similar studies can be conducted in ither contexts as well. Future research can also be undertaken to assess how organizations and leaders are using the lessons learned from the pandemic to effectively manage the future of work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.; methodology, D.S.; software, D.A.-K.; validation, D.S., D.A.-K.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S.; resources, D.A.-K.; data curation, D.S., D.A.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., D.A.-K.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; visualization, D.S.; supervision, D.S., D.A.-K.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, No external funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Royal University for Women, Bahrain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it did not involve any particular institutions and individual participants participated voluntarily based on their individual capacity and consent. Further, all ethical research practices were followed that protected the rights of the participants of this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Written Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Eid, Nawal A., and Boshra A. Arnout. 2020. Crisis and disaster management in the light of the Islamic approach: COVID-19 pandemic crisis as a model (a qualitative study using the grounded theory). Journal of Public Affairs 20: e2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Taji, Farah, and Irene Bengo. 2018. The Distinctive Managerial Challenges of Hybrid Organizations: Which Skills are Required? Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Tammy D., Timothy D. Golden, and Kristen M. Shockley. 2015. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychological Science In The Public Interest 16: 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altork, Kate. 1998. You Never Know When you Want to be a Redhead in Belize. In Inside Stories: Qualitative Research Reflections. Edited by Kathleen B. deMarrais. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, Cláudia, and Eva Petiz Lousã. 2021. Telework and Work–Family Conflict during COVID-19 Lockdown in Portugal: The Influence of Job-Related Factors. Administrative Sciences 11: 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, John, Nicolas Bastardoz, Philippe Jacquart, and Boas Shamir. 2016. An Ill-defined and Ill-measured Gift. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour 3: 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Pallvi, and Divij Suri. 2020. Redefining, Relooking, Redesigning, and Reincorporating HRD in the Post COVID 19 Context and Thereafter. Human Resource Development International 23: 438–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, E. P. Abdul, Dandub Palzor Negi, Asha Rani, and Senthil Kumar A. P. 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 on MigrantWomen Workers in India. Eurasian Geography and Economics 62: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Edited by Caryl Merson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balicer, Ran D., Saad B. Omer, Daniel J. Barnett, and George S. Everly, Jr. 2006. Local public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to an influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health 6: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, Nicole E., Sharlene E. Edwards, and Joann Schulte. 2009. Assessing Public Health Department Employees’ Willingness to Report to Work During an Influenza Pandemic. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 15: 375–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: How the World of Work May Change Forever. BBC. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201023-coronavirus-how-will-the-pandemic-change-the-way-we-work (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Bento, Antonio M., Maureen L. Cropper, Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak, and Katja Vinha. 2005. The Effects of Urban Spatial Structure on Travel Demand in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics 87: 466–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Nicholas, and John Van Reenen. 2008. Measuring and Explaining Management Practices Across Firms and Countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1351–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Ying. 2013. Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130: 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, Richard, D. Raymond, G. McCue, and L. Yamagishi. 1992. Collaborative Autobiography and the Teacher’s Voice. In Studying Teachers’ Lives. Edited by Ivor Goodison. New York: Columbia University, Teachers College Press, pp. 51–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, K. 1993. The Place of Story in Research on Teaching and Teacher Education. Educational Researcher 22: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukir, Jamel, Munirah Sarhan Alqahtani, Essam Khalil, and Elsayed Mohamed. 2022. Effects of Working from Home on Job Performance: Empirical Evidence in the Saudi Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 14: 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrincione, Luigi, Fulvio Plescia, Caterina Ledda, Venerando Rapisarda, Daniela Martorana, Raluca Emilia Moldovan, Kelly Theodoridou, and Emanuele Cannizzaro. 2020. COVID-19 Pandemic: Prevention and Protection Measures to be Adopted at the Workplace. Sustainability 12: 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNN. 2021. The Pandemic Forced a Massive Remote-Work Experiment. Now Comes the Hard Part. CNN. March 11. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/03/09/success/remote-work-covid-pandemic-one-year-later/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Connelly, F. Michael, and D. Jean Clandinin. 1990. Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry. Educational Researcher 19: 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, John W. 2003. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, John W. 2006. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas Ancillo, Antonio, María Teresa del Val Núñez, and Sorin Gavrila Gavrila. 2020. Workplace Change Within the COVID-19 Context: A Grounded Theory Approach. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33: 2297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoeije, Joni, Marijke Verbruggen, and Lynn Germeys. 2019. Boundary Role Transitions: A day-to-day Approach to Explain the Effects of Home-Based Telework on Work-to-Home Conflict and Home-to-Work Conflict. Human Relations 72: 1843–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliotte. 2022. Deliotte Global 2022 Gen Z and Millennial Survey. New York: Deliotte. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, William G. 1994. Work at Home: Data From the CPS. Monthly Labor Review 117: 14–20. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41844241 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Dey, Matthew, Harley Frazis, Mark A. Loewenstein, and Hugette Sun. 2020. Ability to work from home. Monthly Labor Review, 1–19. Available online: https://www.currentcites.org/pub/e270vry5/release/1 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Dirani, Khalil M., Mehrangiz Abadi, Amin Alizadeh, Bhagyashree Barhate, Rosemary Capuchino Garza, Noeline Gunasekara, Ghassan Ibrahim, and Zachery Majzun. 2020. Leadership Competencies and the Essential Role of Human Resource Development in Times of Crisis: A Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. Human Resource Development International 23: 380–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, Simone, Gianluca Viola, Ferdinando Toscano, and Salvatore Zappalà. 2021. Not all remote workers are similar: Technology acceptance, remote work beliefs, and wellbeing of remote workers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 12095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donthu, Naveen, and Anders Gustafsson. 2020. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research 117: 284–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetterman, David M. 1998. Ethnography: Step by Step. Newbury Park: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Fonner, Kathryn L., and Lara C. Stache. 2012. All in a day’s Work, at Home: Teleworkers’ Management of Micro Role Transitions and the Work-Home Boundary. New Technology, Work And Employment 27: 242–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D. 2020. Why You Might be Missing Your Commute. BBC Worklife. May 21. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200519-why-you-might-be-missing-your-commute (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20: 1408–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, Teresa, Gloria Guidetti, Elisabetta Mazzei, Salvatore Zappalà, and Ferdinando Toscano. 2021. Work From Home During the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Impact on Employees’ Remote Work Productivity, Engagement, and Stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63: e426–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthwaite, Josie. 2020. Stanford Researchers Explain How Humanity Has ‘Engineered a World Ripe for Pandemics. Stanford News. April 14. Available online: https://news.stanford.edu/2020/03/25/covid-19-world-made-ripe-pandemics/ (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Gartner. 2020. Gartner HR Survey Reveals 41% of Employees Likely to Work Remotely at Least Some of the Time Post Coronavirus Pandemic. Gartner. April 14. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2020-04-14-gartner-hr-survey-reveals-41--of-employees-likely-to-#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWhile%2030%25%20of%20employees%20surveyed,for%20the%20Gartner%20HR%20practice (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Golden, Lonnie, and Barbara Wiens-Tuers. 2008. Overtime Work and Wellbeing at Home. Review of Social Economy 66: 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, Timothy D., John F. Veiga, and Zeki Simsek. 2006. Telecommuting’s Differential Impact on Work-Family Conflict: Is There no Place Like Home? Journal Of Applied Psychology 91: 1340–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabo, Allen, Brian R. Spisak, and Mark van Vugt. 2017. Charisma as Signal: An Evolutionary Perspective of Charismatic Leadership. The Leadership Quaterly 28: 473–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun. 1997. Introduction to the Theme Issue of “Narrative Perspectives on Research on Teaching and Teacher Education. Teaching and Teacher Education 13: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun. 2001. Narrative Research on School Practice. In Fourth Handbook for Research on Teaching. Edited by Virginia Richardson. New York: MacMillan, pp. 226–40. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, Renata F., Xingyu Wang, Juan M. Madera, and JéAnna Abbott. 2021. Organizational Trust in Times of COVID-19: Hospitality Employees’ Affective Responses to Managers’ Communication. International Journal of Hospitality Management 93: 102778. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0278431920303303 (accessed on 2 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hagaman, Ashley K., and Amber Wutich. 2017. How many interviews are enough to identify metathemes in multisited and cross-cultural research? Another perspective on guest, bunce, and Johnson’s (2006) landmark study. Field Methods 29: 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Lynette. 2003. Home-Based Teleworking and the Employment Relationship. Personnel Review 32: 422–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, H. L. 2002. Whatever is Narrative Research? In Narrative Research: Voices From Teachers and Philosophers. Jyväskylä: SoPhi, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hoti, Irida, Blerta Dragusha, and Valentina Ndou. 2022. Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Albania. Administrative Sciences 12: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalek, Rasha Abdul, and Maged Eid. 2020. Effect of Corona Virus on the Shopping Criteria of Lebanese Consumers. International Journal of Business Marketing and Management (IJBMM) 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kramp, Mary Kay. 2004. Exploring Life and Experience Through Narrative Inquiry. In Foundations of Research: Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences. Edited by Kathleen B. DeMarrais and Stephen D. Lapan. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kyratzis, Amy, and Judith Green. 1997. Jointly Constructed Narratives in Classrooms: Co-Construction of Friendship and Community Through Language. Teaching and Teacher Education 13: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateyka, Peter J., Melanie Rapino, and Liana Christin Landivar. 2012. Home-Based Workers in the United States: 2010; Washington, DC: The United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/demo/p70-132.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Matusik, Sharon F., and Amy E. Mickel. 2011. Embracing or Embattled by Converged Mobile Devices? Users’ Experiences with a Contemporary Connectivity Technology. Human Relations 64: 1001–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, R. 2021. Remote Employees Are Working Longer than Before. SHRM. July 6. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-news/pages/remote-employees-are-working-longer-than-before.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Mazmanian, Melissa, Wanda J. Orlikowski, and JoAnne Yates. 2013. The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals. Organization Science 24: 1337–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. 2020. To Emerge Stronger From the COVID-19 Crisis, Companies Should Start Reskilling Their Workforces Now. McKinsey & Company. May 7. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/to-emerge-stronger-from-the-covid-19-crisis-companies-should-start-reskilling-their-workforces-now (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- McKinsey. 2021. The Future of Work After COVID-19. McKinsey & Company. February 18. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19 (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Moen, Torill. 2006. Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methodology 5: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moingeon, Bertrand, and Guillaume B. Soenen. 2004. Corporate and Organizational Identities. London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtarian, Patricia L., Michael N. Bagley, and Ilan Salomon. 1998. The Impact of Gender, Occupation, and Presence of Children on Telecommuting Motivations and Constraints. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 49: 1115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Jane Kellogg. 2020. 50% of Remote Employees Miss Their Commute (and Other Surprising Things People Miss Most about Working in the Office). Indeed Career Guide. November 13. Available online: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/covid-19-what-people-miss-most-about-office-work?utm_campaign=earnedsocial%3Acareerguide%3Asharetwitter%3AUS&utm_content=50%25+of+Remote+Employees+Miss+Their+Commute+%28and+Other+Surprising+Things+People+Miss+Most+About+Working+in+the+Office%29&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Ng, Matthew A., Anthony Naranjo, Ann E. Schlotzhauer, Mindy K. Shoss, Nika Kartvelishvili, Matthew Bartek, Kenneth Ingraham, Alexis Rodriguez, Sara Kira Schneider, Lauren Silverlieb-Seltzer, and et al. 2021. Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Accelerated the Future of Work or Changed Its Course? Implications for Research and Practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 10199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, Brian. 2021. Don’t Micromanage during the Coronavirus. SHRM. July 6. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/people-managers/pages/coronavirus-micromanaging.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Osborne, H. 2021. Home Workers Putting in More Hours Since COVID, Research Shows. The Guardian. February 4. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/04/home-workers-putting-in-more-hours-since-covid-research (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Pachler, Norbert, and Caroline Daly. 2009. Narrative and Learning with Web 2.0 Technologies? Towards a Research Agenda. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 25: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prawat, R. 1996. Constructivism, Modern and Postmodern. Educational Psychologist 31: 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. 2020. Upskilling for the new Normal. PwC. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/c1/en/future-of-government-cee/covid19/Upskilling_for_the_new_normal.html (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- PwC. 2021. It’s Time to Reimagine Where and How Work Will Get Done. PwC. January 12. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/library/covid-19/us-remote-work-survey.html (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Sengupta, Debashish. 2017. The Life of Y’–Engaging Millennials as Employees and Consumers. New Delhi: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, Debashish, and Dwa Al-Khalifa. 2022. Motivations of Young Women Volunteers during COVID-19: A Qualitative Inquiry in Bahrain. Administrative Sciences 12: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplilearn. 2020. How COVID-19 Has Affected Employee Skills Training: A Simplilearn Survey. Simplilearn. July 2. Available online: https://www.simplilearn.com/how-covid-19-has-affected-employee-skills-training-article (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Smith, Richard. 1996. Distance is Dead: The World Will Change. BMJ 313: 1572–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sonnentag, Sabine, Eva J. Mojza, Carmen Binnewies, and Annika Scholl. 2008. Being Engaged at Work and Detached at Home: A Week-Level Study on Work Engagement, Psychological Detachment, and Affect. Work & Stress 22: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]