1. Introduction

In 2020, Vietnam’s tourism faced many difficulties due to the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic. In addition to solutions to overcome difficulties and prevent the epidemic, there has been an attempt to restructure the tourist market (

Chen et al. 2020). In this context, the development of human resources needs to be given more attention to be ready for the recovery and implementation of sustainable tourism development strategies in the future.

Like other industries, human resources are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills that play an important role in the development of tourism products as well as travel services. This is also considered one of the key factors that increase competitiveness and survival in the tourism market for each of the country’s businesses, localities, and tourism industries (

Carnevale and Hatak 2020). According to the General Department of Tourism (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism), each year, the whole industry needs approximately 40,000 employees, but the current number of students graduating in the tourism field is approximately 15,000 people; more than 12% of these have college or university degrees or higher. In many localities with thriving tourism industries, human resources are always a difficult issue because of the workforce, especially the serious lack of direct labor. There is a large gap in the number of employees in the hotel industry compared to the number of workers needed in the future. There are increasing requirements for improving the quality of human resources and transparency in the recruitment market. Choosing the right staff is a big challenge. Competition for personnel in the industry will lead to employees’ intending to quit and transfer jobs, affecting business operations, financial costs, human resource management, and employee cohesion in hotel operations (

Zavei and Jusan 2012).

In that context, leadership and leadership style are the key factors that help businesses overcome difficulties. Studies show that being a good leader takes a lot of effort, knowledge, skills, and especially leadership style. Leadership does not always mean applying only one leadership style to every employee, but choosing a leadership style that is appropriate for their qualifications (

AlShehhi et al. 2020;

Asrar-Ul-Haq et al. 2020;

Tafvelin 2013). Many people fail to manage the team because they are not aware of this point; they set requirements that are too high for new employees or give good employees too little space to be proactive and creative at work. This causes subordinates to lack confidence in the leader or obey, but not feel comfortable developing their full capacity. Therefore, if the leader wants to exploit the human resources of the team or company (i.e., talent, intelligence, enthusiasm of employees), the leader needs to understand that leadership is different and how to effectively lead an employee or team in practice. Previous studies have demonstrated the success of transformational leadership in delivering employee satisfaction and employee motivation in the tourism industry (see

Khan et al. 2020;

Li et al. 2020;

Mittal and Dhar 2016;

Mohamed 2016;

Vargas-Sevalle et al. 2020). However, these studies have not yet clarified the specific relationship of these factors. Leadership transforms into employee satisfaction and work motivation. In addition, in Vietnam, studies mainly focus on the factors affecting work motivation (see

Bích and Tuẩn 2013) or factors affecting employee satisfaction (

Võ 2019). However, few studies have assessed the relationship between the factors of transformation leadership, satisfaction, and employee motivation. In the context of the complicated COVID-19 epidemic, the tourism industry will still face many difficulties. This is the time for leaders of travel agencies, hotels, restaurants, transportation, and entertainment spots to retain employees, encourage employees to work hard and work with the business to overcome challenges and prepare conditions to welcome tourists back after the pandemic. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the influence of transformation leadership factors on employee satisfaction and motivation in the context of the complicated COVID-19 epidemic.

Transformational leadership is the leader’s ability to motivate followers to rise above their own personal goals for the greater good of the organization (

Elbaz and Haddoud 2017;

Guay 2013). It was theorized that the transformational style of leadership comes from deeply held personal values that cannot be negotiated and appeal to subordinates’ sense of moral obligation and values. Transformational leaders go beyond transactional leadership and are characterized as visionary, articulate, assured, and able to engender confidence in others to motivate them to surpass their usual performance goals. Transformational leaders attempt to stimulate the undeveloped or dormant needs of their subordinates. Intellectual stimulation represents the cognitive development of the follower and occurs when the leader arouses followers to think in new ways and emphasizes problem-solving and the use of reasoning before taking action. The idea is that the transformational leadership style can help tourism organizations overcome the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic by encouraging teamwork, opinion sharing, and effectively tackling crises. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the influence of transformation leadership factors on employee satisfaction and motivation in the context of the complicated COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Literature Review

It was reported that over the last few decades, organizations have had relatively significant success with various kinds of transformational leadership models. A leading example is Kouzes and Posner’s (see

Kouzes and Posner 2007) model, which offers a leadership model with five distinct practices that outstanding leaders use to influence employees’ performance. This model consists of some of the key elements of transformational leadership styles. The five practices of exemplary leadership are:

(a) challenging the process: searching and seizing challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate, and improve, with the willingness to take risks and learn from mistakes;

(b) inspiring a shared vision: enlisting followers’ support in a shared vision by appealing to the followers’ values, interests, and aspirations;

(c) enabling others to act: achieving common goals by building mutual trust, empowering followers, developing competence, assigning critical tasks, and providing continuous support;

(d) modeling the way: being a role model and being consistent with shared values, and

(e) encouraging the heart: providing recognition for success and celebrating accomplishments.

Relationship theories, also known as transformational theories, focus on the connections formed between leaders and followers (

Khan et al. 2020). In these theories, leadership is the process by which a person engages with others and is able to “create a connection” that results in increased motivation and morality in both followers and leaders. Relationship theories are often compared to charismatic leadership theories in which leaders with certain qualities, such as confidence, extroversion, and clearly stated values, are seen as best able to motivate followers (

Lamb 2013).

Relationship or transformational leaders motivate and inspire people by helping groups of members understand the importance and higher purpose of the task. These leaders are focused not only on the performance of members but also on the ability of each person to fulfill their potential. Leaders of this style often have high ethical and moral standards (

Cherry et al. 2012).

Xian et al. (

2020) examined the relationship between transformation leadership and removing employees’ work-related uncertainties and ambiguity when facing an uncertain environment; the results showed that there was a strong significant relationship between transformational leadership and uncertainty reduction among employees. Moreover, the results also revealed that supervisor involvement boosted employee morale as a contributing factor to ambiguity and uncertainty reduction. As stated by

Andreani and Petrik (

2016), if the leader understands the differences in each employee and appropriately recognizes employees’ work, they will feel satisfied because they are valued individually.

Kreitner and Kinicki (

2007) found that employees love their jobs if they are arranged properly according to their expertise which they devote to the organization. Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction not only delve into the nature of the job, but also depend on the expectations of employees on the job (

Mahmoud 2008). Job satisfaction is a complex phenomenon with many aspects that are affected by factors such as salary, working environment, self-control, communications, and organizational commitment.

Naeem and Khanzada (

2018) explained that leadership style has a strong impact on employee job satisfaction and that different leadership styles also influence job satisfaction and employee motivation.

Shafi et al. (

2020) show the positive relationship between transformation and employee creativity, while

Zareen et al. (

2015) concluded that among three types of leadership styles (transactional, transformational, and laissez-faire), the transactional leadership style has the strongest impact on employee motivation.

Related to leadership in the tourism industry,

Mao et al. (

2020) also discussed leadership style impacts on employee self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism through employee satisfaction with corporate COVID-19 responses. The data collected from 505 travel agents operating in Egypt,

Elbaz and Haddoud (

2017) show that not all leadership styles have a positive influence on employee satisfaction. Their study also shows that a positive influence takes place through the development of wisdom leadership. Its creators note that the questionnaire represents an effort to collect as much information as possible for leadership behaviors—from avoidance to idealized leadership—while it differentiates effective leaders from ineffective (

Puni et al. 2018). It focuses on individual behaviors and leader characteristics, which are evaluated by their colleagues, regardless of their position, and in relation to leader-evaluators (

Vasudeva and Nayan 2019). Transformational leadership is based on 4 elements described by Bernard A. Bass (

Bass 1985;

Bass and Riggio 2006): Idealized Influence, Intellectual Stimulation, Individualized Consideration, and Inspirational Motivation. The brief explanations are as follows:

- -

Idealized influence describes a leader who appears to be special, acts as a role model for followers and has strong ethical and moral values. Followers aspire to resemble such leaders and want to follow them.

- -

Inspirational motivation refers to how transformational leaders set high standards and expectations for their followers and demonstrate absolute confidence in the follower’s ability to meet or exceed the targets set.

- -

Intellectual stimulation describes how transformational leaders encourage their followers to question not only their beliefs and values but also those of the leader. Through this rigorous and open examination Bass believes that opportunities for personal growth, innovation and creativity are discovered.

- -

Idealized consideration refers to how transformational leaders listen to the needs and problems of their followers and act as guide, mentor and coach with the aim of moving each follower closer to self-actualization.

Bass’s model of transformational leadership has been embraced by scholars and practitioners alike as a measure in which organizations can encourage employees to perform beyond expectations. Despite the degree of interest in transformational leadership, a number of theoretical issues have been identified with this model. Moreover, there is ambiguity concerning the differentiation of the sub-dimensions of transformational leadership. Empirically, this issue has been reflected in a lack of support for the hypothesized factor structure of the transformational model and for the discriminant validity of the components of the model with each other. As a result, various studies re-examine the Bass model to identify five sub-dimensions of transformational leadership that will demonstrate discriminant validity with each other and with outcomes. A lot of studies (

AlShehhi et al. 2020;

Andreani and Petrik 2016;

Braun et al. 2013) suggest that it is appropriate to examine the individual leadership sub-dimensions as opposed to a higher-order transformational leadership factor. The five-factor leadership model is as follows:

(1) Vision: Vision is identified as an important leadership dimension encompassed by the more general construct of charisma. Bass’s model argued that the most general and important component of transformational leadership is charisma. Empirical findings support this statement, with meta-analytic results indicating that charisma is most strongly associated with measures of effectiveness such as satisfaction with the leader.

Vision is the expression of a desired picture of the future based around organizational values and should answer this basic question: What do we want to become? In addition to knowing and understanding direction, transformational leaders must be able to clearly communicate the vision and validate that it was understood as intended.

(2) Inspirational communication: Inspirational communication is the expression of positive and encouraging messages about the organization, and statements that build motivation and confidence. Transformational leaders continually seek to understand changing factors that motivate people to do their best work.

Inspirational communication seems to be particularly important when expressing a vision for the future. In the absence of encouragement and confidence building efforts, articulating a vision may have a neutral or even negative influence on employees.

(3) Supportive leadership: Prior discussions of individualized consideration have focused on one component of this construct, supportive leadership. Supportive leader expresses concern for their followers and takes into account their individual needs.

Supportive leader behavior is described as ‘‘behavior directed toward the satisfaction of subordinates’ needs and preferences, such as displaying concern for subordinates’ welfare and creating a friendly and psychologically supportive work environment.

(4) Intellectual stimulation: A leader with intellectual stimulation always encourages innovation and creativity, as well as critical thinking and problem-solving. Intellectual stimulation is related to arousing employees’ thoughts and imagination, as well as stimulating their ability to identify and solve problems creatively. Intellectual stimulation enhances employees’ interest in and awareness of problems, and it helps to increase creative problem-solving skills, encouraging them to think about problems in new ways.

(5) Personal recognition: Personal recognition can be defined as the provision of rewards such as praise and acknowledgement of effort for achievement of specified goals. When an employee receives recognition for their work, they feel an increased sense of investment in an organization.

Since its introduction, the five-factor leadership model has been the focal point of numerous studies. However, there are limited studies on the relationship between transformation leadership, job satisfaction, and employee motivation in the tourism industry, and the transformational leadership factor should be revised. As a result, this study attempts to develop the theory for tourism leadership style to identify five sub-dimensions of transformational leadership that will demonstrate discriminant validity with each other and with outcomes. Tourism staff is said to have low motivation, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (

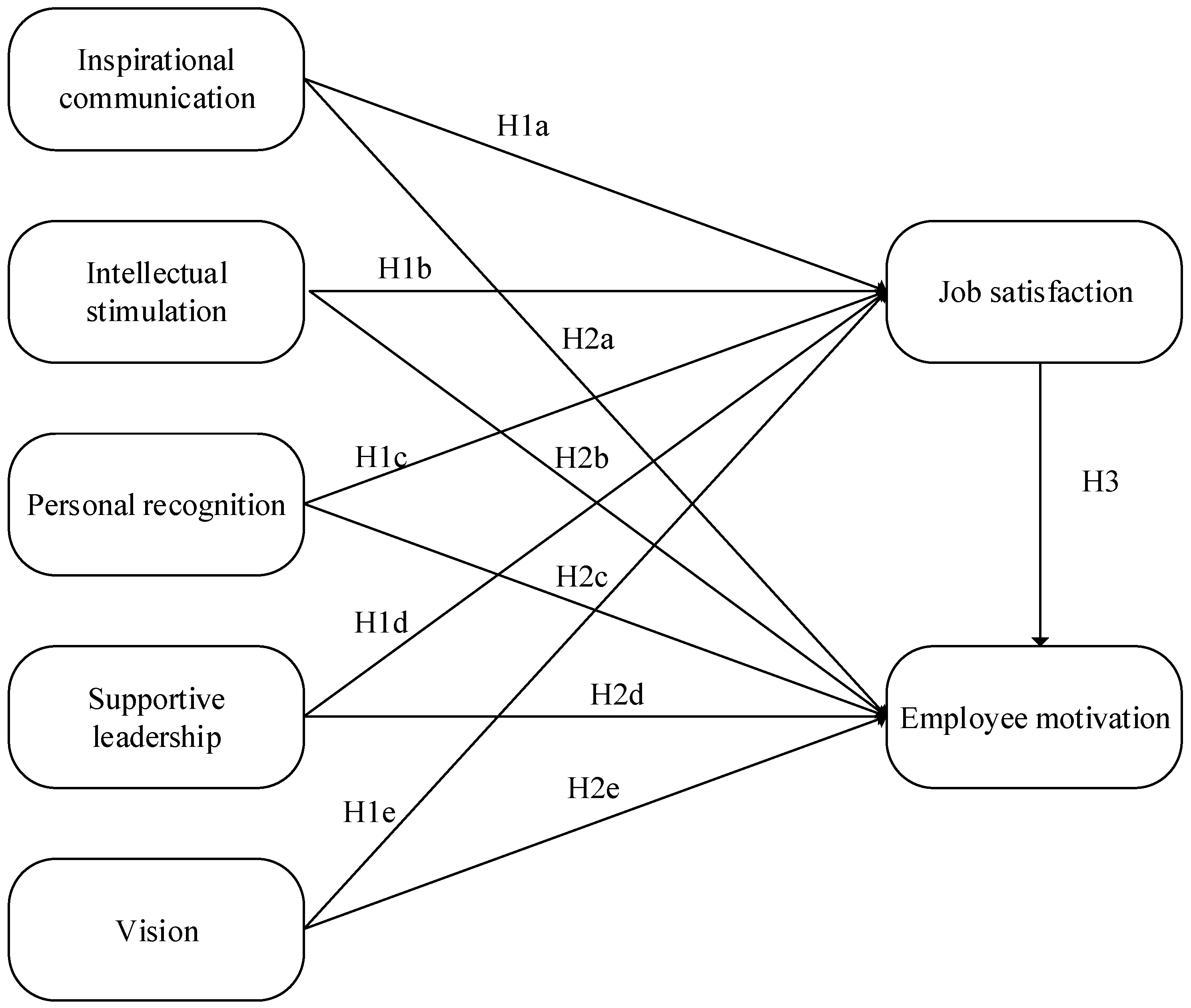

Sobaih et al. 2020). Based on the above discussions, the following hypotheses are proposed (see

Figure 1):

H1a. There is a relationship between inspirational communication as a dimension of transformation leadership style and job satisfaction in VTI.

H1b. There is a relationship between intellectual stimulation as a dimension of transformation leadership style and job satisfaction in VTI.

H1c. There is a relationship between the personal recognition as a dimension of transformation leadership style and job satisfaction in VTI.

H1d. There is a relationship between supportive leadership as a dimension of transformation leadership style and job satisfaction in VTI.

H1e. There is a relationship between vision as a dimension of transformation leadership style and job satisfaction in VTI.

H2a. There is a relationship between inspirational communication as a dimension of transformation leadership style and employee motivation in VTI.

H2b. There is a relationship between intellectual stimulation as a dimension of transformation leadership style and employee motivation in VTI.

H2c. There is a relationship between the personal recognition as a dimension of a transformation leadership style and employee motivation in VTI.

H2d. There is a relationship between the supportive leadership as a dimension of the transformation leadership style and employee motivation in VTI.

H2e. There is a relationship between vision as a dimension of transformation leadership style and employee motivation in VTI.

H3. There is a relationship between job satisfaction and employee motivation in VTI.

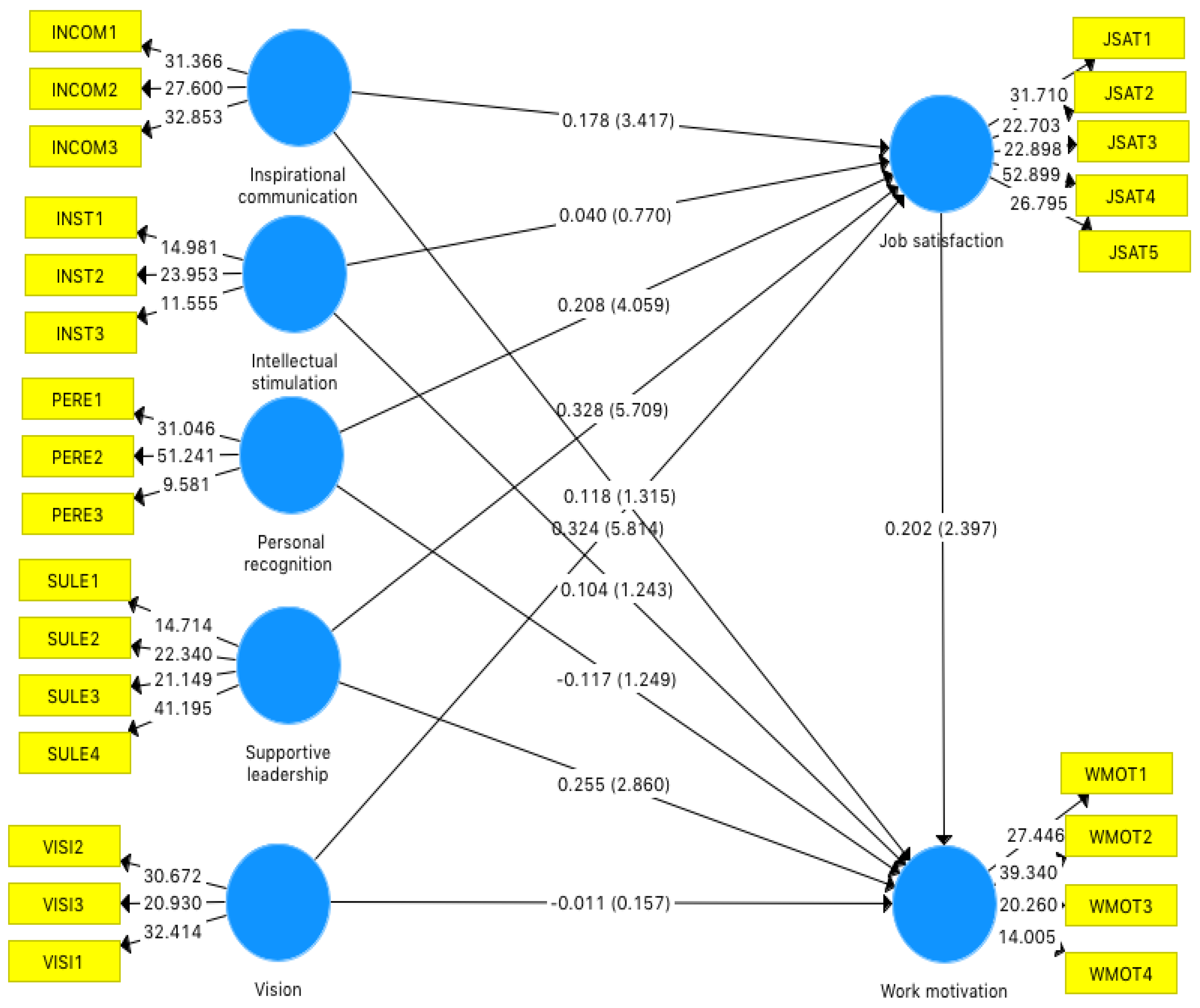

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study primarily to investigate the relationship between transformation leadership, job satisfaction, and employee motivation in the Vietnam tourism industry (VTI) has been fulfilled. The study has boldly put forward an opinion on the leadership capacity of tourism industry managers as a basis for fully defining the components of transformation leadership in relation to job satisfaction and employee motivation in the Vietnam tourism industry. The study applied and developed partial least squares (PLS-SEM) to assess the leadership capacity of the tourism industry in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We successfully applied and transformed the scale of leadership that has been used in Vietnam and in the world for research in Northern Vietnam. The study proposes and develops a model for measuring the influence of factor groups on the transformation leadership of tourism managers, while in Vietnam, there are very few studies that deal with this topic. Existing documents on organizational prestige (

Shafi et al. 2020;

Vasudeva and Nayan 2019) have identified management capacity and leadership quality as the key drivers of the prestige of organizations, especially in crisis situations. The findings of this study provide new evidence from the perspective of employees that there are effective leadership styles such as leadership change (in terms of strategy, charisma, inspiration). It also contributes to the positive perception of employees about the reputation of the organization, while the leader of total authority does not make this positive. According to

Sobaih et al. (

2020), leadership style plays an important role in creating the organization’s working environment as well as the internal environment that influences the attitude and motivation of employees that help organizations overcome difficult situations. Therefore, to enhance positive internal credibility through word of mouth and supportive behaviors, transformational leadership styles should be strengthened and developed rather than full-fledged leadership styles, as evidenced by the present study.

Research results show that the transformation leadership style has a positive effect on employee perceptions of organizational prestige, which is not only direct but also indirect through enhancement. The status of employee leadership, which includes a common vision and high-performance expectations, contributes to the role model and enhances collaboration among employees to achieve entry. At the same time, we emphasize the quality of the relationship among employees and show interest in individual feelings as well as direct benefits to foster positive perceptions of organizations and beliefs in the future after the pandemic. These findings are consistent with previous research on the positive correlation between a change leadership style and employee attitudes (

Al-Rafee and Cronan 2006;

Sobaih et al. 2020) as well as satisfaction (

Freeborough and Patterson 2016;

Long et al. 2014), and positive emotions such as joy, pride, admiration, and love (

Andreani and Petrik 2016). By sharing benefits with employees and allowing employees to participate in decision-making, leadership transfer not only makes employees feel more confident, more accepting, trustworthy, and valuable, but also forms a positive view of employees in the organization (

Shafi et al. 2020). The results of this research will be the basis for tourism company managers to consult and improve their knowledge, skills, and leadership qualities to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, it is the basis for the relevant departments of the region to develop policies to support the leadership capacity of tourism industry managers in the future.

The outcomes of this study suggested recommendations that have to be directed to top managerial level in the tourism industry. The managers within this industry should be trained to use a transformational leadership style to motivate their employees and release their maximum potential to progress beyond their capacity in performing at workplace. Managers should create a realistic and achievable vision for the organization, and communicate such vision effectively to their followers. They should provide constant conviction that such vision is attainable, and inspire multiple sense of purpose and commitment that will enhance the followers’ satisfaction. In a developing economy such as Vietnam, leadership in the workplace, especially in tourism industry, is encouraged to embrace a leadership style that will improve the working conditions of employees, giving recognition to individuals. Managers should also meet the follower needs, including recognition, fulfillment, and meaningfulness, thereby increasing their satisfaction.

Despite these pioneering initiatives, research still faces some shortcomings that need to be addressed in future research, such as the limited use of samples only in Northern Vietnam. However, the value of research is in theoretical testing rather than its generalized meaning. A second limitation is due to the prevalence of certain collection sources. The data are collected primarily from the perspective of the employee. For a more comprehensive understanding of how an organization’s leadership style affects employee satisfaction and motivation, professionals should work with organizational leaders and combine research cooperation initiatives. In future studies, samples from a wide variety of organizations across different sectors need to be used to test the proposed model and to synthesize the research results. Qualitative research methods such as in-depth interviews with corporate leaders should also be used to concurrently explain the different perspectives on research issues. As the transformational leadership style has not been fully researched, future research will focus on how the leader interacts with other factors; for example, how managers interact with different leadership styles and different dependent variables, such as commitment, engagement, and loyalty, and how effective leadership styles interact with the organization.