Perspective of Critical Factors toward Successful Public–Private Partnerships for Emerging Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- What are the critical success factors of PPP in Albania?

- -

- What is the relation between the factors and the success of PPP?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public–Private Partnership

2.2. Critical Success Factors of Public-Private Partnership

3. Methodology

- -

- Negotiation is an important process as it is also mentioned in the above definition; it is the right of negotiation in the procurement process to negotiate the terms/conditions of the supplier. Even in the Albanian case, this process includes the elements to what extent the contracts can be negotiated, the limitations and the responsibilities.

- -

- Trust, openness and fairness between the parties is an important item which is identified by the survey’s answers as a crucial element for the PPPs’ success. The context is the same where partnering should be mutually viewed as an opportunity for reaching an objective and achieving good results based on transparency and openness between the private and private sector.

- -

- Sufficient social capital, defined revenue stream and financial capacity go hand in hand in the case of Albania, as the country is in a developing phase where the opportunity to ensure a good private partner relies on its capacity to provide the needed resources. In the Albanian case there are difficulties considering the limited resources.

- -

- The identification of the right project and the feasibility study are very significant considering that there are many projects under the concession’s practice which raises many questions as to their importance and the financial capacity of the government to handle such model. This is linked with other factors: community and stakeholders’ support, as the general public is sometimes skeptical on certain concessions, i.e., as to whether they should be implemented by private entities. A successful practice of PPP should be based on the support of the general community; however, in Albania this is still a topic of discussion. For example, the battle for the Vjosa river gained a new dimension in 2017, with the arrival of 30 European scientists, who explored the central course of the river: the segment where the construction of the dams was designed. While the initial results confirmed the existence of extraordinary biological diversity, the Albanian government approved a dam project, precisely at the time when scientific research was ongoing. In 2018, Vjosa gained further international attention. The Bern Convention (International Treaty for the Conservation of Nature) recommended that Albania suspend dam projects on this river. At the same time, the European Parliament recommended a review of the renewable energy strategy, in order to reduce the dependence of energy production on hydropower plants. This is related with the Statutory Environment and Environmental impact, which clearly defines the legal framework but also considers the financial and/or environmental impact, as in the case of Vjosa river.

- -

- Lastly, as for the other items: the compatibility of skills among the parties, the potential synergy with each other, and inter-departmental cooperation. The public sector’s organized structure is the same in that it includes the importance of collaboration between the entities to achieve the results and the importance of a well-organized internal structure for a better flow of delegated tasks.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. General Characteristics of the Respondents

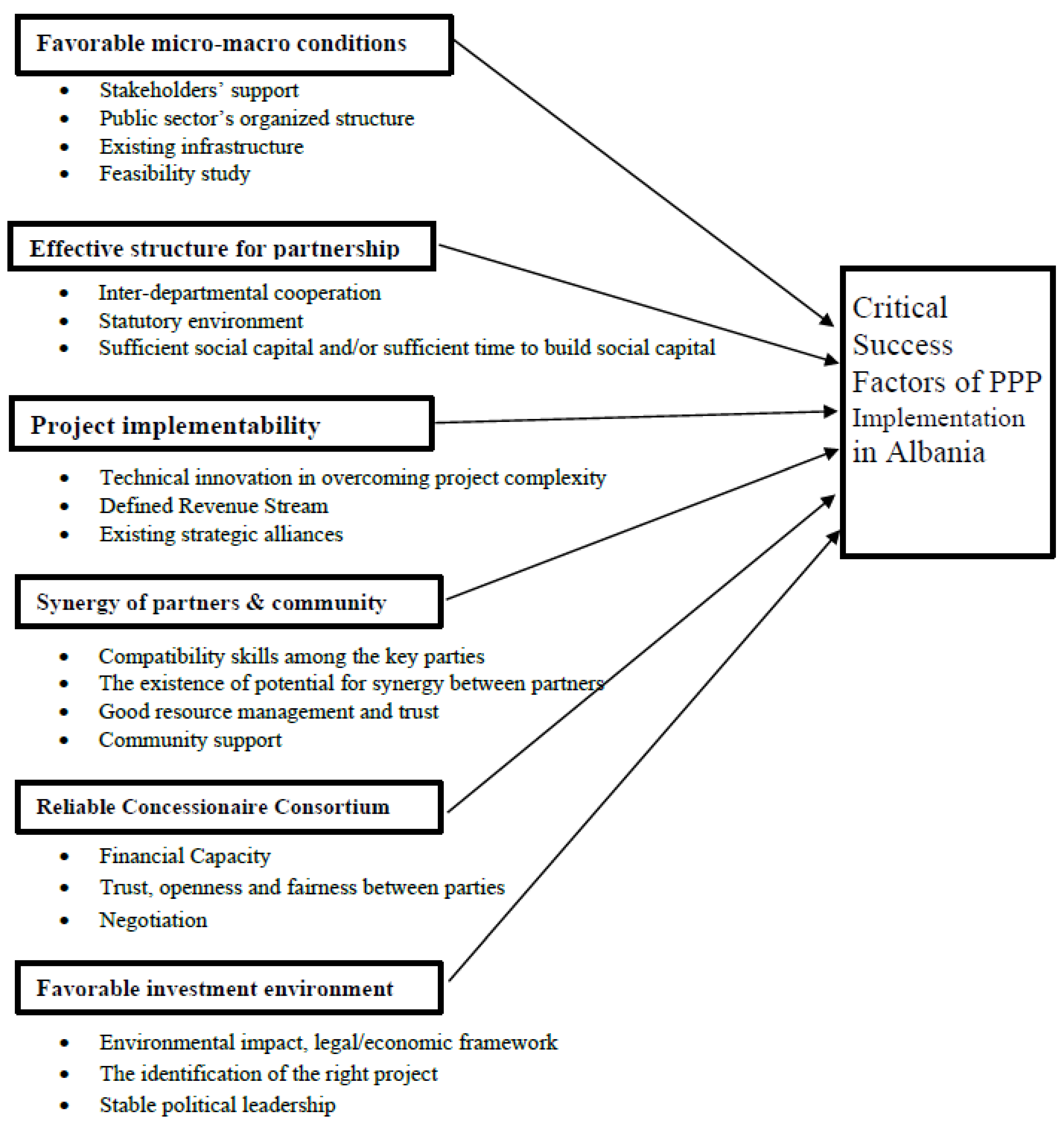

4.2. CSF of PPP Implementation

5. Discussion

5.1. Favorable Micro–Macro Conditions

5.2. Effective Structure for Partnership

5.3. Reliable Concessionaire Consortium

5.4. Project Implementability

5.5. Favorable Investment Environment

5.6. Synergy of Partners and Community

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Comparison between Countries Concerning the Top Five Items for PPP Implementation

| No. | Top Five Items for Albania | Top Five Items for Different Countries (Cheung et al. 2012) | ||

| China (Hong Kong) | Australia | UK | ||

| 1 | The identification of the right project | Favorable legal framework | Commitment and responsibility of public and private sectors | Strong and good private consortium |

| 2 | Financial capacity | Commitment and responsibility of public and private sectors | Appropriate risk allocation and risk sharing | Appropriate risk allocation and risk sharing |

| 3 | Trust, openness and fairness between parties | Strong and good private consortium | Strong and good private consortium | Available financial market |

| 4 | Negotiation | Stable macro-economic condition | Good governance | Commitment and responsibility of public and private sectors |

| 5 | Defined revenue stream | Appropriate risk allocation and risk sharing | Project technical feasibility | Thorough and realistic assessment of the costs and benefits |

Appendix B. Questionnaire

- (a)

- Executive director

- (b)

- Head of department

- (c)

- Representative of investors

- (d)

- Manager

- (e)

- Other (please specify) _______________________________

- (a)

- Not at all important

- (b)

- Low importance

- (c)

- Neutral

- (d)

- Moderately Important

- (e)

- Extremely important

- (a)

- 1–3 years

- (b)

- 3–6 years

- (c)

- 6–9 years

- (d)

- +10 years

- (a)

- 1–3 projects

- (b)

- 3–5 projects

- (c)

- 5–7 projects

- (d)

- +8 projects

- (a)

- Service contract

- (b)

- Managerial contract

- (c)

- Lease

- (d)

- Concession

- (e)

- Other (please specify) _________________________

- (a)

- No affect

- (b)

- Minor affect

- (c)

- Neutral

- (d)

- Moderate affect

- (e)

- Major affect

Appendix C. Critical Success Factors for PPP Project

| CSF/s | 1—Not Important at All | 2—Of Little Importance | 3—Of Average Importance | 4—Very Important | 5—Absolutely Important |

| Stakeholders’ support | |||||

| Public sector’s organized structure | |||||

| Existing infrastructure | |||||

| Feasibility study | |||||

| Inter-departmental cooperation | |||||

| Statutory environment | |||||

| Sufficient social capital and/or sufficient time to build social capital | |||||

| Technical innovation in overcoming project complexity | |||||

| Defined revenue stream | |||||

| Existing strategic alliance | |||||

| Compatibility skills among the key parties | |||||

| The existence of potential for synergy between partners | |||||

| Good resource management and trust | |||||

| Community support | |||||

| Financial Capacity | |||||

| Trust, openness and fairness between parties | |||||

| Negotiation | |||||

| Environmental impact, legal/economic framework | |||||

| The identification of the right project | |||||

| Stable political leadership |

References

- Ahmeti, Eni, and Alba Demneri Kruja. 2020. Challenges and Perspectives of Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: A Case Study Approach. In Leadership Strategies for Global Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 132–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Management Association. 2018. Project Management: How to Build Interdepartmental Cooperation. New York: AMA. [Google Scholar]

- Asllani, Arben, Richard Becherer, and Qirjako Theodhori. 2014. Developing a sustainable economy through entrepreneurship: The case of Albania. South-Eastern Europe Journal of Economics 12: 243–62. [Google Scholar]

- Beqiraj, Rovena, Gazmir Vehbi, Andi Memi, and Eljon Shkodrani. 2016. Koncesionet dhe Partneriteti Publik Privat: Manual per perdoruesit. Tirana: ATRAKO, HMH. [Google Scholar]

- Bitzenis, Aristidis, and Ersjana Nito. 2005. Obstacles to entrepreneurship in a transition business environment: The case of Albania. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12: 564–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Esther, Albert Chan, Patrick Lam, Daniel Chan, and Yongjian Ke. 2012. A comparative study of critical success factors for public private partnerships (PPP) between Mainland China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Facilities 30: 647–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Zbysław. 2021. Are the supreme audit institutions agile?: A cognitive orientation and agility measures. European Research Studies Journal 24: 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Zbysław, Wereda Wioletta, and Saczyńska-Sokół Sylwia. 2015. Relationship management in a public-private partnership. Hyperion International Journal of Econophysics and New Economy 8: 510–18. [Google Scholar]

- Feruni, Nerajda, and Eglantina Hysa. 2020. Free trade and gravity model: Albania as part of central European free trade agreement (CEFTA). In Theoretical and Applied Mathematics in International Business. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 60–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grimsey, Darin, and Mervyn K. Lewis. 2007. Public Private Partnerships: The Worldwide Revolution in Infrastructure Provision and Project Finance. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle, Cliff, Peter J. Edwards, Akintola Akintoye, and Bing Li. 2005. Critical Success Factors for PPP/PFI Projects in the UK Construction Industry: A factor Analysis Approach. Construction Management and Economics 5: 479–51. [Google Scholar]

- Helmy, Mohamed Ahmed. 2011. Investigating the Critical Success Factors For PPP Projects In Kuwait. Master’s Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Department of Real Estate and Construction Management, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Hoon, Young, Kwak Ying Chih, and C. William Ibbs. 2009. Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Public Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development. California Management Review 51: 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hysa, Eglantina, and Egla Mansi. 2021. Challenges of Sustainable Economic. In Journal of Financial and Monetary Economics. Bucharest: “Victor Slăvescu” Centre for Financial and Monetary Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hysa, Eglantina, Alba Kruja, Naqeeb Ur Rehman, and Rafael Laurenti. 2020. Circular economy innovation and environmental sustainability impact on economic growth: An integrated model for sustainable development. Sustainability 12: 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Suhaiza, and Shochrul Rohmatul Ajija. 2013. Critical success factors of public private partnership (PPP) implementation in Malaysia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 5: 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima. 2004. Success and failure mechanisms of public private partnerships (PPPs) in developing countries: Insights from the Lebanese context. International Journal of Public Sector Management 5: 414–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, Marcus. 2006. Critical success factors of public private sector partnerships: A case study of the Sydney SuperDome. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 3: 451–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, Marcus, Rod Gameson, and Steve Rowlinson. 2002. Critical success factors of the BOOT procurement system: Reflections from the Stadium Australia case study. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 4: 352–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keçi, Julinda. 2020. Public-private partnerships in Albania: From the legislative provisions to risk management. Paper presented at 4th International Balkans Conference on Challenges of Civil Engineering, BCCCE, EPOKA University, Tirana, Albania, December 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Syed Abdul Rehamn, Zhang Yu, Mirela Panait, Laeeq Razzak Janjua, and Adeel Shah, eds. 2021. Global Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives for Reluctant Businesses. Hershey: IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Kruja, Alba. 2020a. Entrepreneurial orientation, synergy and firm performance in the agribusiness context: An emerging market economy perspective. Central European Business Review 9: 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruja, Alba Demneri. 2020b. Entrepreneurial challenges of Albanian agribusinesses: A content analysis. JEEMS Journal of East European Management Studies 25: 530–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruja, Alba Demneri, and Anisa Berisha. 2021. UK-Albania Tech Hub: Enhancing Tech Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Albania. Tirana: British Embassy Tirana. [Google Scholar]

- Maione, Gennaro, Daniela Sorrentino, and Alba Demneri Kruja. 2021. Open Data for Accountability at Times of Exception: An Exploratory Analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 16: 231–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, Otilia, Eglantina Hysa, and Alba Kruja. 2021. Finances and National Economy: Frugal Economy as a Forced Approach of the COVID Pandemic. Sustainability 13: 6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, Otilia, Mirela Panait, Eglantina Hysa, Elena Rusu, and Maria Cojocaru. 2022. Public procurement, a tool for achieving the goals of sustainable development. Amfiteatru Economic 61: 861–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnie, Johan A. 2011. Critical Success Factors for Public-Private Partnerships in South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- MONITOR. 2019. 200 VIP-at e 2018, viti i koncesioneve. September 27. Available online: https://www.monitor.al/200-vip-at-e-2018-viti-i-koncesioneve-2/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Nasto, Kostandin, and Junada Sulillari. 2021. Public-private partnerships: A profitability analysis of the partnerships in the energy sector in Albania. Fundamental and Challenging Issues in Scholarly Research 106: 106, 112. [Google Scholar]

- NCPPP. 2017. 7 KEYS TO SUCCESS. December 15. Available online: https://www.ncppp.org/ppp-basics/7-keys/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Ndonye, Hussein N., Emma Anyika, and George Gongera. 2014. Evaluation of Public Private Partnership Strategies on Concession Performance: Case of Rift Valley Railways Concession, Kenya. European Journal of Business and Management 6: 145, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, Jum C. 1978. An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. Cham: Springer, pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Parvu, Daniela, and Cristina Voicu-Olteanu. 2009. Advantages and limitations of the public private partnerships and the possibility of using them in romania. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 5: 189–98. [Google Scholar]

- Plaku, Dorina, and Eglantina Hysa. 2019. The impact of tax policies on behavior of Albanian taxpayers. In Behavioral Finance and Decision-Making Models. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 219–50. [Google Scholar]

- Preci, Gjovalin. 2016. Partneriteti Publik Privat në këndvështrimin auditues të KLSH. SOT News, December 15. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Michael R. 2000. Public–private partnerships for public health. Nature Medicine 6: 617–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinkel, Briget K., Christopher Cormier, James L. Zheng, and Md Shamsur Saikat. 2016. Exploring Albania’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Massachusetts, United States: Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/445 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Rockart, John F. 1982. Future role of the Information systems executive. MIS Quarterly 6: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, Steve. 1999. A definition of procurement systems. In Procurement Systems: A Guide to Best Practice in Construction. London: Routledge, pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sanni, Afeez Olalekan. 2016. Factors determining the success of public private partnership projects in Nigeria. Construction Economics and Building 16: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soecipto, Raden Murwantara, and Koen Verhoest. 2018. Contract stability in European road infrastructure PPPs: How does governmental PPP support contribute to preventing contract renegotiation? Public Management Review 20: 1145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahiu, Artan. 2020. Public-private partnership: An analysis of the legal features of PPP instrument in the Albanian reality. European Journal of Business and Management Research 5: 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, Robert L., and Jahidul Alum. 1997. Evaluation of proposals for BOT projects. International Journal of Project Management 15: 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomja, Elsa. 2016. Partneritetet Publik-Privat dhe Faktorët Kritikë Të Suksesit në Implementimin e Tyre në Shqipëri. Durres: Universiteti Aleksander Mojsiu. Available online: https://vdocuments.net/partneritetet-publik-privat-dhe-faktort-kritik-t-suksesit-viewuesit-sipas-se.html (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- WBIF, and EPEC. 2018. PPP Projects in the Western Balkans: Good Practice, Challenges and Lessons Learnt. Luxemburg: European Investment Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Xheneti, Mirela, and David Smallbone. 2008. The role of public policy in entrepreneurship development in post-socialist countries: A comparison of Albania and Estonia. EBS Review 24: 23–36. Available online: http://www.ebs.ee/file.php?21947 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Zhang, Xueqing. 2005. Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Development. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 10: 212–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/s | Country | Sample Surveyed | Type of PPP | Methodology | Critical Success Factors of PPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiong and Alum (1997) | Asia-Pacific region | BOT practitioners | Concession BOT contract | → Use of surveys; → Quantitative study. Analysis: Descriptive analysis. |

|

| Jefferies et al. (2002) | Australia | NA | Concession BOOT contract | → Use of interviews and literature; → Qualitative study. Analysis: single case study method. |

|

| Jamali (2004) | Lebanon | NA | Concession BOT contract | → Use of documentation, archival records, interviews and quantitative assessment; → Quantitative and qualitative study. Analysis: quantitative comparative assessment. |

|

| Hardcastle et al. (2005) | UK | Directors and managers working in public and private sector’s organizations | General PPPs No specification | → Use of surveys; → Quantitative study. Analysis: Descriptive analysis, reliability tests using Cronbach’s alpha, One-Way Analysis of Variance and Factor Analysis. | Effective procurement; Project implementability; Government guarantee; Favorable economic conditions Available financial market. |

| Minnie (2011) | South Africa | Public service entities and private service entities | Concessions | → Use of interviews, the analysis of case studies, surveys and the use of informants; → Quantitative and qualitative study. Analysis: Descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, mean, and standard deviation. - Independent sample t-test. |

|

| Helmy (2011) | Kuwait | Kuwaiti middle and low-income citizens who would be eligible for the welfare housing units from the government. | Concession BOT contract | → Use of interviews and questionnaires; → Qualitative and quantitative study. Analysis: Factor analysis. |

|

| Ismail and Ajija (2013) | Malaysia | Participants of the national seminar on Malaysian PPP framework | General PPPs No specification | → Use of surveys; → Quantitative study. Analysis: independent sample t-test and mean score (by SPSS). | Good governance; Commitment and responsibility of public and private sectors; Favorable legal framework; Sound economic policy; Available financial market; Strong and good private consortium; Stable macro-economic condition; Project technical feasibility; Transparency of procurement process; Appropriate risk allocation and risk sharing; Thorough and realistic assessment of the cost and benefits; Well-organized and committed public agency Multi-benefit objectives; Competitive procurement process Social support; Shared authority between public and private sectors; Government involvement by providing guarantee; Political support. |

| Sanni (2016) | Nigeria | Survey: Participants who have played key roles in the implementation of PPP projects from public and private sectors. Interviews: experts on PPP projects | General PPPs No specification | → Use of questionnaires and interviews; → Quantitative and qualitative study. Analysis: Cronbach’s alpha, exploratory factor analysis, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin Measure (KMO), Measures of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) and factor extraction. | Stable macro-economic conditions; Commitment and responsibility of public/private sectors; Available financial market; Strong private consortium; Repayment of the debt; Sound financial package; Strong political support; Delivering publicly needed service; Short construction period; Economic viability of the project; Innovation in the financial methods of consortium; Favorable legal framework. |

| Item | Definition | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Negotiation | Through the right negotiation in the procurement process it is possible, under the new public procurement directive, to ensure that the private party will be responsible for the funding, design, completion, implementation, service and maintenance, providing the incentive to build to reduce the life-time cost of service and maintenance. | (Jefferies 2006) |

| Trust, openness and fairness between parties | “Partnering should be mutually viewed as representing an opportunity rather than a threat and loss of control. In this context, while recognizing the immense complexities in working across sectors with different strategic and operational realities, the focus should be on identifying common goals, delineating responsibilities, negotiating expectations, and building bridges including common working practices and specific reporting and record keeping requirements”. | (Jamali 2004) |

| Sufficient social capital and/or sufficient time to build social capital | “Sufficient social capital to accommodate the social capital requirements of the partnership and/or sufficient time to build social capital”. | (Minnie 2011) |

| Financial capacity | “Financial capacities to ensure strong financial base and reliable partner, and municipal attitudes”. | (Minnie 2011) |

| Stable political leadership | “The simplest definition of a stable political system is one that survives through crises without internal warfare”. | (Minnie 2011) |

| Statutory environment | “Statutory authority and regulations—Necessary for enforcement of the contract”. | (NCPPP 2017) |

| Public sector’s organized structure | Need for good governance

| (NCPPP 2017) |

| Stakeholder support | “All impacted parties End Users Competing Interests”. | (NCPPP 2017) |

| Environmental impact, legal /economic framework | A PPP legal framework is identified in laws and regulations, but also in policy documents, guidance notes and in the design of PPP contracts. The exact nature of the legal and regulatory framework applicable to a particular PPP transaction, also depends on the financing mechanisms contemplated and the scope of responsibilities transferred to the PPP company. | (Jefferies et al. 2002) |

| Existing strategic alliances | This experience or network is viewed favorably. A local partner in an international BOOT contributes greatly towards success. Experience viewed in terms of country (previous host). | (Jefferies et al. 2002) |

| Community support | Social groups of any size whose members reside in a specific locality, share government, and often have a common cultural and historical heritage. | (Tiong and Alum 1997) |

| Existing infrastructure | Contracts for the procurement of services or management of existing infrastructure can be divided into two categories.

| (Jefferies 2006) |

| Defined revenue stream | “Funds to Cover the Long-Term Financing

| (NCPPP 2017) |

| Feasibility Study | “Not all projects are suited to BOOT. Public and private agreement over the advantages the concept has to offer needs to be found. Project feasibility must show evidence of viability”. | (Jefferies et al. 2002) |

| The identification of the right project | PPP project identification will be undertaken by the contracting authority, or the line ministry concerned. Project identification should include input from stakeholders as follows: Contracting Agencies:

| (Tiong and Alum 1997) |

| The existence of potential for synergy between partners | It does seem as if the potential for synergy must exist before one could say that a partnership will be a good idea and would therefore be a possible reason for partnering. A second assumption is that a partnership involves both development and delivery of a strategy or a set of projects or operations, although each actor may not be equally involved in all stages. | (Minnie 2011) |

| Good resource management and trust | It is crucial to have good governance because inefficiency in governance has led to the failure in the implementation of PPP in many countries. | (Jefferies et al. 2002) |

| Inter-departmental cooperation | Public sector inter-departmental cooperation is the in support of partnership. | (Minnie 2011) |

| Compatibility skills among the key parties | Parties exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use, and seek independent advice, if necessary, based on cooperation with each other. | (Jefferies et al. 2002) |

| Rotated Component Matrix a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Stakeholders’ support | 0.873 | |||||

| Public sector’s organized structure | 0.790 | |||||

| Existing infrastructure | 0.716 | |||||

| Feasibility study | 0.550 | |||||

| Inter-departmental cooperation | 0.690 | |||||

| Statutory environment | 0.609 | |||||

| Sufficient social capital and/or sufficient time to build social capital | 0.533 | |||||

| Technical innovation in overcoming project complexity | 0.805 | |||||

| Defined revenue stream | 0.767 | |||||

| Existing strategic alliances | 0.675 | |||||

| Compatibility skills among the key parties | 0.436 | |||||

| The existence of potential for synergy between partners | 0.772 | |||||

| Good resource management and trust | 0.638 | |||||

| Community support | 0.503 | |||||

| Financial capacity | 0.742 | |||||

| Trust, openness and fairness between parties | 0.682 | |||||

| Negotiation | 0.622 | |||||

| Environmental impact, legal/economic framework | 0.465 | |||||

| The identification of the right project | 0.733 | |||||

| Stable political leadership | 0.719 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berisha, A.; Kruja, A.; Hysa, E. Perspective of Critical Factors toward Successful Public–Private Partnerships for Emerging Economies. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040160

Berisha A, Kruja A, Hysa E. Perspective of Critical Factors toward Successful Public–Private Partnerships for Emerging Economies. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040160

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerisha, Anisa, Alba Kruja, and Eglantina Hysa. 2022. "Perspective of Critical Factors toward Successful Public–Private Partnerships for Emerging Economies" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040160

APA StyleBerisha, A., Kruja, A., & Hysa, E. (2022). Perspective of Critical Factors toward Successful Public–Private Partnerships for Emerging Economies. Administrative Sciences, 12(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040160