Success Factors of Startups in Research Literature within the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (RQ1):

- What aspects, from those previously identified by business practice, make a startup succeed or fail, according to the literature?

- (RQ2):

- What is the relative importance of the success factors?

- (RQ3):

- What are the factors that mainly explain the success of a startup?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Success Factors in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

- Timing:

- synchronization in the time of launch to market (supply) of the product or service and demand.

- Team:

- cohesion and the capability for joint execution.

- Idea:

- value, disruptive capacity, or market fit.

- Business model:

- style or model chosen to increase the number of users or customers.

- Funding:

- obtaining the appropriate or necessary amount of funds at each development stage.

- Decision strategy of the CEO (Chief Executive Officer; usually the founder), or the Leadership that he or she provides.

- Marketing strategy used: the marketing activities carried out and the “mix” of channels used to launch the company.

- Culture of non-stop evaluation: the start-up has some KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) for its analysis and has constant evaluation in its DNA.

- Culture and/or existing values within the start-up: the culture of its founders and their ability to instill certain values in their team.

- Ability to adapt to the environment: the ability to adapt to changes produced by a dynamic environment in which the start-up must operate (Díaz-Santamaría and Bulchand-Gidumal 2021).

- Internal satisfaction within the start-up: optimism, internal climate.

- Culture of training and/or development: seeing training as the basis for sustained growth and continuous innovation.

- Diversity in the start-up: diversified staff.

- Advisors or business board: it is essential to have a differentiated advisory team that has an impact on the decisions of the start-up.

- Lean Start-up: the presence and active use of this methodology.

- Previous experience of the Founders in the sector or business in which the start-up operates.

2.2. Background and Literature

3. Method

3.1. Analysis Procedure

3.2. Sample: Stages and Process

- Stage 1. Selection and quality assesment of articles

- Full entrepreneurial and startup focus in a Google Scholar search.

- Stage 2. Data systematization

- Stage 3. Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Text Analysis: Data Mining

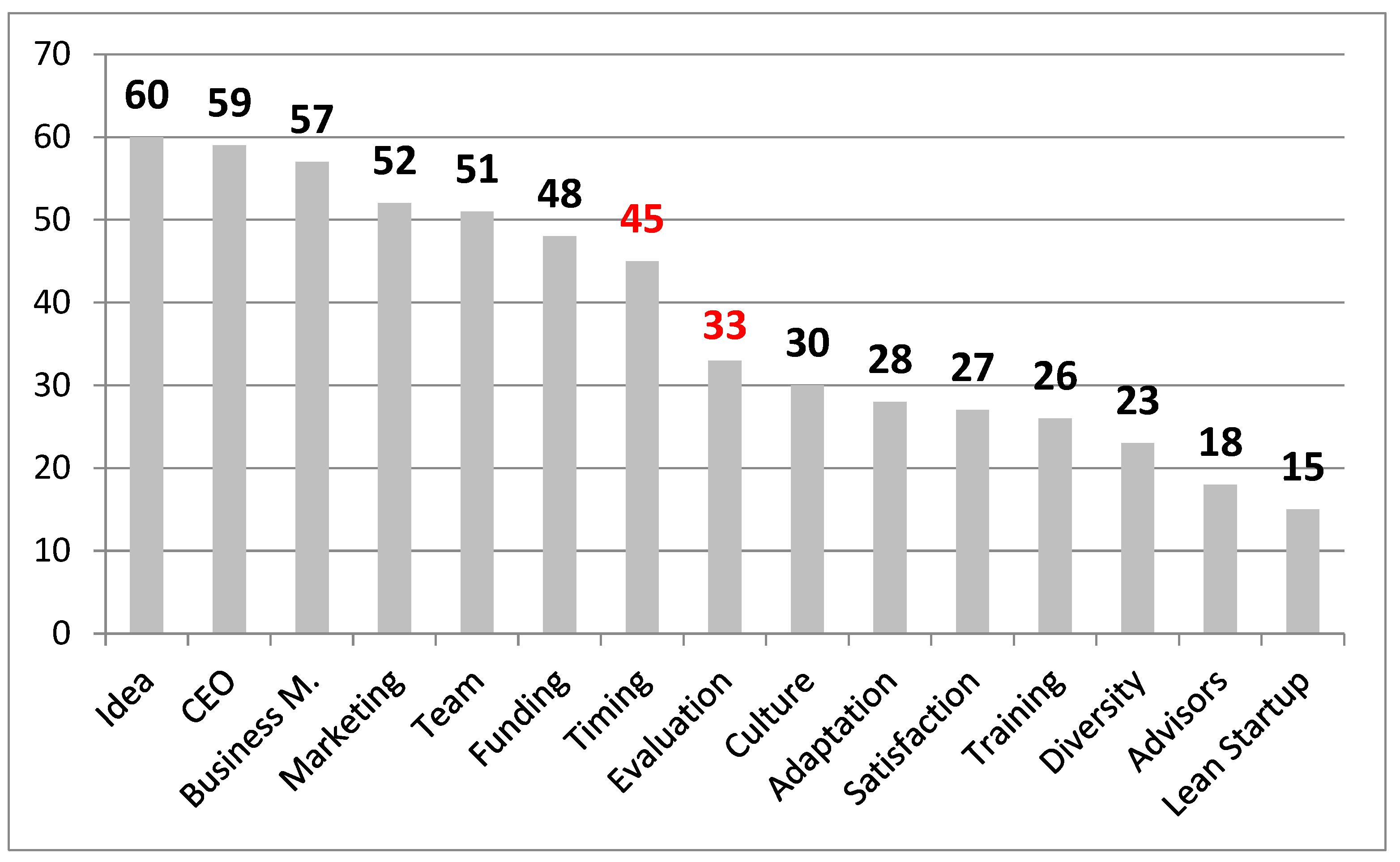

- Idea: present in the 60 articles analyzed

- Decisions of the CEO

- Business model

- Marketing

- Team

- Funding

- Timing

- Evaluation Culture

- Culture and Values of the Start-up

- Adaptation to the environment

4.2. The Main Factors for Entrepreneurial Performance

- CEO Decisions, in the second position.

- The type of Marketing Strategy, in fourth position.

| Ranking Results in This Paper | Weight | Gross (2015) | Weight | Berkus (2006) | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Idea | 10.5% | Timing | 42% | Idea | 20% |

| 2 | CEO Decisions | 10.3% | Team | 32% | Founding Team | 20% |

| 3 | Business Model | 10.0% | Idea | 28% | Operational Prototype | 20% |

| 4 | Marketing | 9.1% | Business Model | 24% | Strategic Relations | 20% |

| 5 | Team | 8.9% | Funding | 14% | Traction or Revenues | 20% |

| 6 | Funding | 8.4% | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | Timing | 7.9% | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | Others (8 factors) | 35% | - | - | - | - |

5. Success Factors and Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

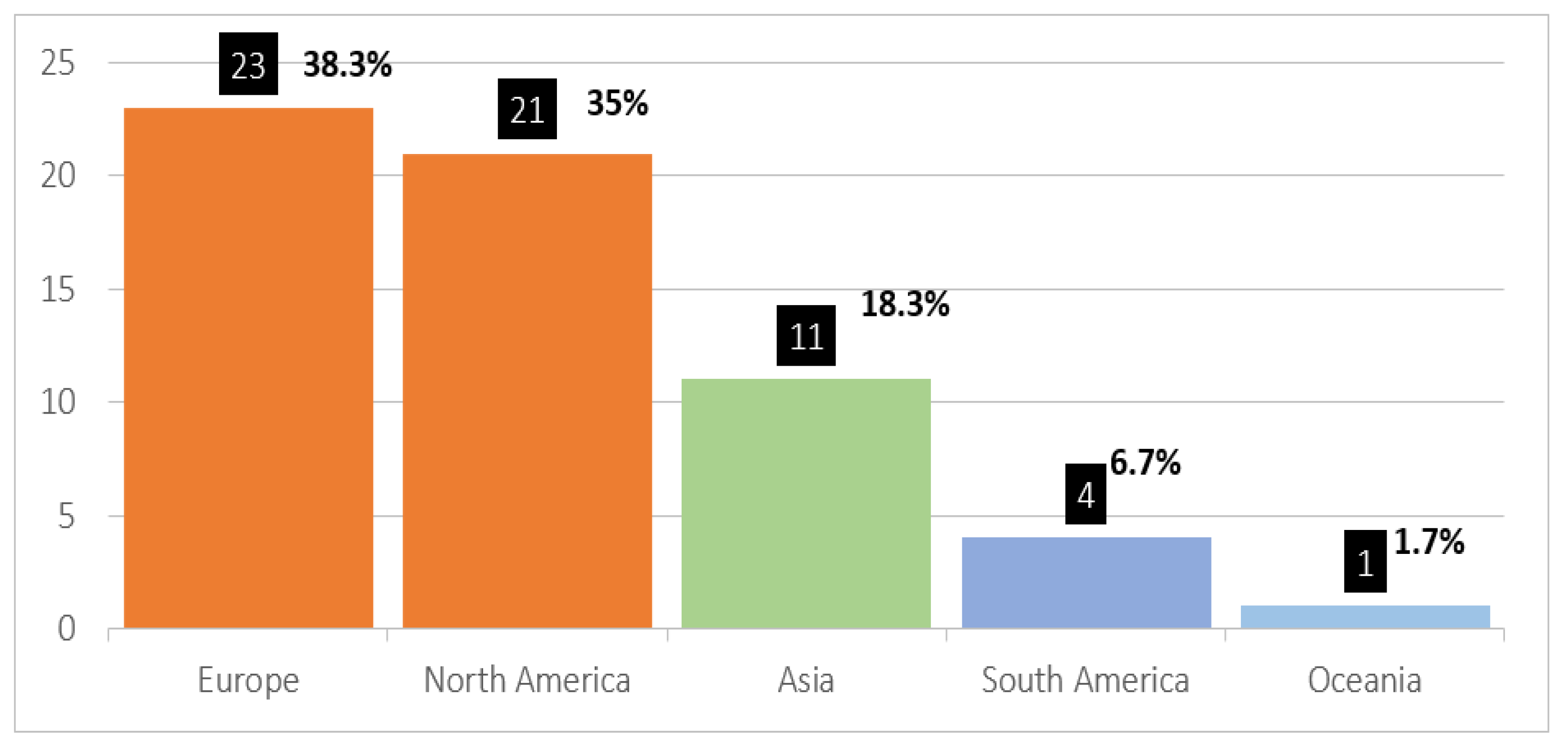

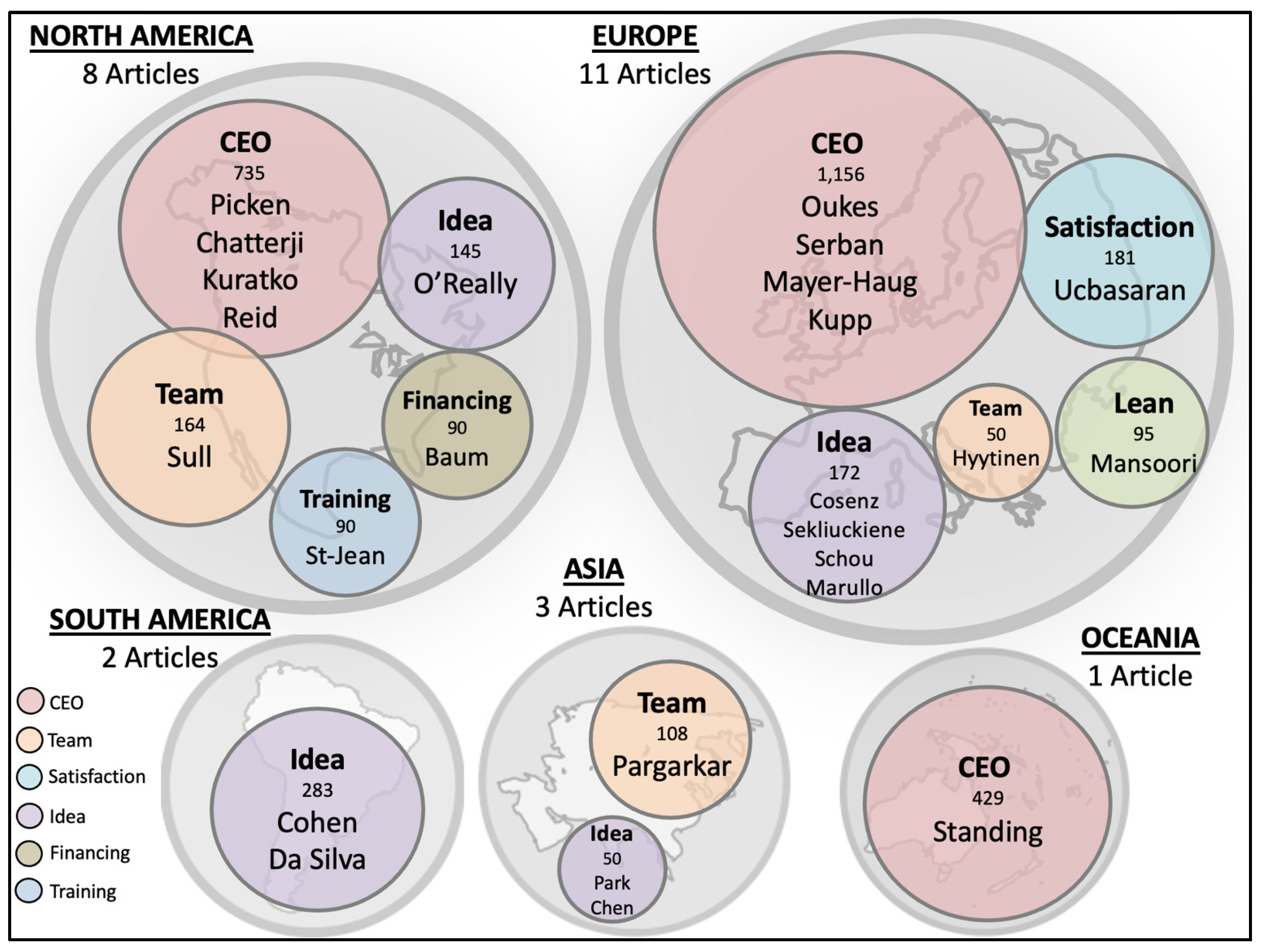

5.1. Analysis of Main Success Factors by Location

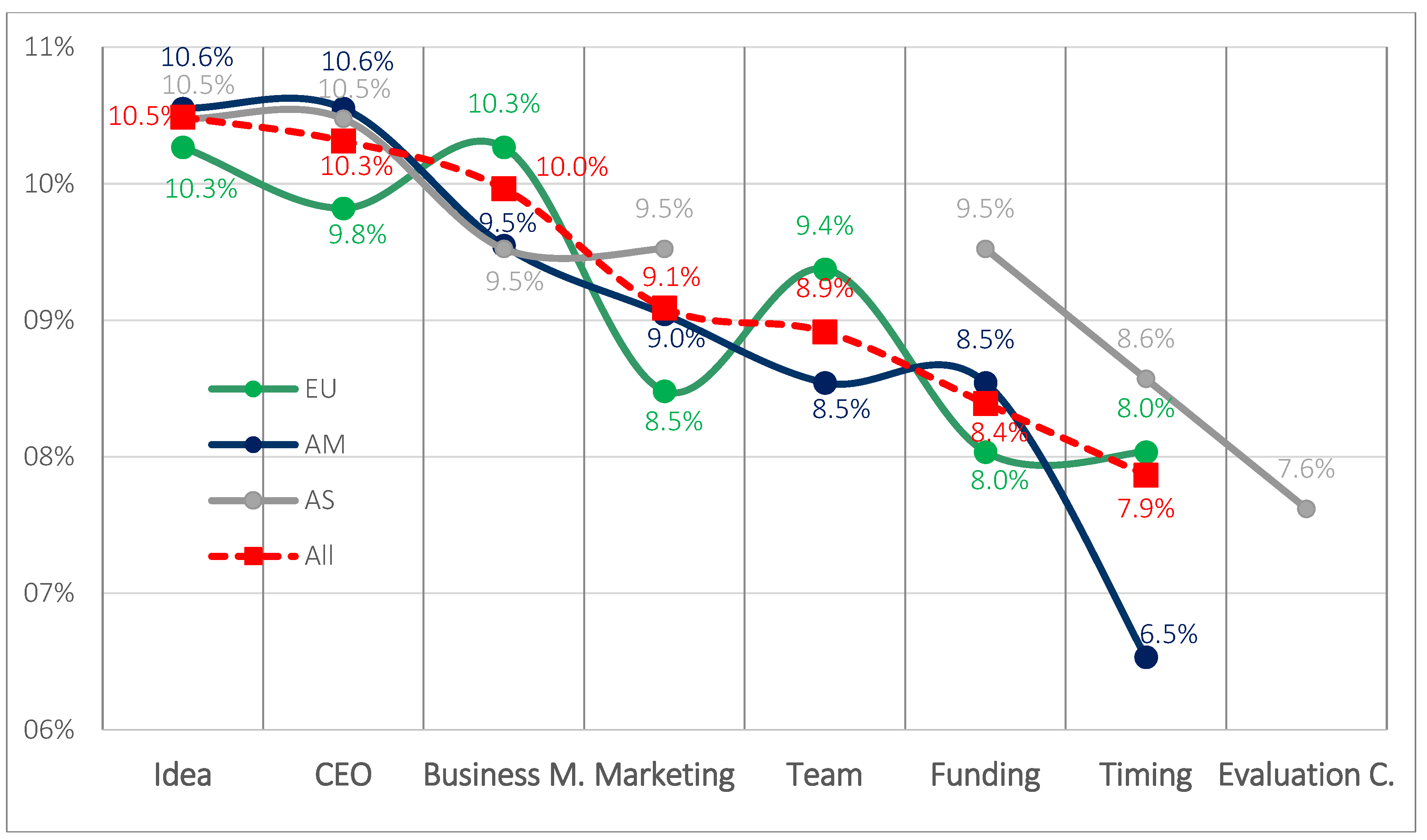

- The Idea factor is always the first, or the “Top 1” in all the continents analyzed (see Appendix B with data in tables). In Europe the Idea and Business Model factors are crucial; they are equally valued and occupy the first position. However, for North America, Idea and CEO are the most important factors and reach an above-average score.

- In Europe (EU), and especially in Asia, the Timing factor is dominant. In North America, however, timing registers the smallest percentage.

- The Business model factor is considered very important in Europe, even surpassing the factor considered second on average, which is the CEO factor. Therefore, Business Model is the second most important factor in Europe, rather than CEO.

- For Asia, the Marketing factor is very relevant, but in Europe this factor achieves the smallest score, which is considerably lower than the average obtained by all the areas.

- Marketing is the fourth factor in terms of relative importance in all areas except Europe, where the fourth place is occupied by Team.

- The group of seven factors remains similar in North America (in the same order) and in Europe (with a rise in the rankings of the Business Model and Team factors) but is different in Asia, here the order of the factors changes remarkably because the Team factor goes to the eighth place thereby abandoning the established ranking of the seven factors. The Culture of Evaluation appears in the ranking and is more important than the Team only for Asia.

- The Funding factor is the last one for all areas except Asia, where it reaches a preferential position regarding the other continents; it achieves the same score than Business model and Marketing (see Appendix B). these three factors occupy the third place among all factors for Asia.

5.2. Multidimensional Mapping of Success Factors in Start-Ups Companies

6. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

- CEO Decisions appear in the second position. This factor encompasses the decision-making skills of the CEO, the ability to build a team, and the capacity for individual execution.

- The type of Marketing used is in fourth position. This factor is related to the execution of marketing campaigns and the selection of the appropriate marketing mix channels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Number of Articles | Percentage |

| The United States | 18 | 30% |

| England | 4 | 7% |

| The Netherlands | 4 | 7% |

| Italy | 3 | 5% |

| Canada | 3 | 5% |

| Brazil | 3 | 5% |

| Singapore | 2 | 3% |

| South Korea | 2 | 3% |

| France | 2 | 3% |

| Spain | 2 | 3% |

| Thailand | 1 | 2% |

| Sweden | 1 | 2% |

| Portugal | 1 | 2% |

| Malaysia | 1 | 2% |

| Lithuania | 1 | 2% |

| Japan | 1 | 2% |

| Israel | 1 | 2% |

| Iran | 1 | 2% |

| India | 1 | 2% |

| Finland | 1 | 2% |

| Denmark | 1 | 2% |

| China | 1 | 2% |

| Chile | 1 | 2% |

| Belgium | 1 | 2% |

| Austria | 1 | 2% |

| Australia | 1 | 2% |

| Germany | 1 | 2% |

| TOTAL | 60 | 100% |

| Source: own elaboration. | ||

Appendix B

| NORTH AMERICA | ASIA | ||||||

| Ranking | Factor | Presence | Weight | Ranking | Factor | Presence | Weight |

| 1 | Idea | 21 | 10.6% | 1 | Idea | 11 | 10.5% |

| 2 | CEO | 21 | 10.6% | 2 | CEO | 11 | 10.5% |

| 3 | Business model | 19 | 9.5% | 3 | Business model | 10 | 9.5% |

| 4 | Marketing | 18 | 9.0% | 4 | Marketing | 10 | 9.5% |

| 5 | Team | 17 | 8.5% | 5 | Funding | 10 | 9.5% |

| 6 | Funding | 17 | 8.5% | 6 | Timing | 9 | 8.6% |

| 7 | Timing | 13 | 6.5% | 7 | Evaluation Culture | 8 | 7.6% |

| TOTAL WEIGHT 7 FACTORS | 63.3 | TOTAL WEIGHT 7 FACTORS | 65.7 | ||||

| 8 | Culture | 11 | 5.5% | 8 | Team | 8 | 7.6% |

| 9 | Evaluation Culture | 11 | 5.5% | 9 | Satisfaction | 6 | 5.7% |

| 10 | Satisfaction | 11 | 5.5% | 10 | Advisors | 5 | 4.8% |

| 11 | Training | 10 | 5.0% | 11 | Adaptation | 5 | 4.8% |

| 12 | Adaptation | 9 | 4.5% | 12 | Culture | 4 | 3.8% |

| 13 | Advisors | 8 | 4.0% | 13 | Diversity | 3 | 2.9% |

| 14 | Diversity | 8 | 4.0% | 14 | Training | 3 | 2.9% |

| 15 | Lean Start-up | 5 | 2.5% | 15 | Lean Start-up | 2 | 1.9% |

| SOUTH AMERICA | EUROPE | ||||||

| Ranking | Factor | Presence | Weight | Ranking | Factor | Presence | Weight |

| 1 | Idea | 4 | 12.1% | 1 | Idea | 23 | 10.3% |

| 2 | CEO | 4 | 12.1% | 2 | Business model | 23 | 10.3% |

| 3 | Business model | 4 | 12.1% | 3 | CEO | 22 | 9.8% |

| 4 | Marketing | 4 | 12.1% | 4 | Team | 21 | 9.4% |

| 5 | Team | 4 | 12.1% | 5 | Marketing | 19 | 8.5% |

| 6 | Timing | 4 | 12.1% | 6 | Funding | 18 | 8.0% |

| 7 | Culture | 2 | 6.1% | 7 | Timing | 18 | 8.0% |

| TOTAL WEIGHT 7 FACTORS | 78.8 | TOTAL WEIGHT 7 FACTORS | 64.3 | ||||

| 8 | Evaluation Culture | 2 | 6.1% | 8 | Culture | 13 | 5.8% |

| 9 | Funding | 2 | 6.1% | 9 | Adaptation | 12 | 5.4% |

| 10 | Advisors | 1 | 3.0% | 10 | Diversity | 12 | 5.4% |

| 11 | Adaptation | 1 | 3.0% | 11 | Evaluation Culture | 11 | 4.9% |

| 12 | Training | 1 | 3.0% | 12 | Training | 11 | 4.9% |

| 13 | Diversity | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | Satisfaction | 10 | 4.5% |

| 14 | Lean Start-up | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | Lean Start-up | 7 | 3.1% |

| 15 | Satisfaction | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | Advisors | 4 | 1.8% |

| OCEANIA | |||

| Ranking | Factor | Presence | Weight |

| 1 | Business model | 1 | 9.1% |

| 2 | CEO | 1 | 9.1% |

| 3 | Adaptation | 1 | 9.1% |

| 4 | Evaluation | 1 | 9.1% |

| 5 | Funding | 1 | 9.1% |

| 6 | Idea | 1 | 9.1% |

| 7 | Lean Start-up | 1 | 9.1% |

| TOTAL WEIGHT 7 FACTORS | 63.6 | ||

| 8 | Marketing | 1 | 9.1% |

| 9 | Timing | 1 | 9.1% |

| 10 | Team | 1 | 9.1% |

| 11 | Training | 1 | 9.1% |

| 12 | Advisors | 0 | 0.0% |

| 13 | Culture | 0 | 0.0% |

| 14 | Diversity | 0 | 0.0% |

| 15 | Satisfaction | 0 | 0.0% |

| Source: own elaboration. | |||

Appendix C

| Author | Objective | Results |

| (Baum and Silverman 2004) | Venture capital companies: they choose successful start-ups or build the success of the start-up. | The technological capacity is important, but also those start-ups that need advice on business management. The most influential factors for investment are: partnerships, patents, and good management skills. |

| (Chatterji et al. 2019) | To explore the influence of the advice that entrepreneurs receive. | Mentors with a formal approach to managing people made them grow by 28% and were 10% less likely to fail than those working with an informal approach to people management. |

| (Chen and Zhu 2008) | Success in entrepreneurs with an academic background compared to no background whatsoever. | Academic characteristics (going to university) are detrimental to economic performance. However, they have a positive influence on growth, number of employees, and satisfaction. |

| (Cohen and Kietzmann 2014) | Explore sustainable and emerging business models by analysing their relationship with local government. | Greater integration between shared mobility operators and cities has the potential to minimise conflicts between government agencies and increase the sustainability of the business model. Objective: to be aligned with the results expected by government agencies. |

| (Cosenz and Noto 2018) | The objective is to simplify the knowledge of a business system. | Exploration of different strategic solutions using simulation. The results show that the use of clear KPIs promotes growth. |

| (Hyytinen et al. 2015) | Association between the innovation of a start-up and its survival. | The survival rate (3 years of life) of a company dedicated to innovation is 7–8 percentage points lower (56% on average) than the average survival rate of new companies not dedicated to innovation (63% on average). |

| (Kupp et al. 2017) | Corporate accelerators as an object of study. | Five success factors for corporate acceleration programmes were identified: clear objectives (transparency and alignment with the organisation), start-up promoters, large external network, management support, and definition of clear KPIs. |

| (Kuratko et al. 2007) | Investigate the relationship between stakeholder visibility, the position of the organization, and business intensity. | If the corporate entrepreneur considers how he or she can create value for the company’s stakeholders, corporate entrepreneurship will have a much greater chance of success than simply focusing on reducing costs or short-term profits. |

| (Mansoori et al. 2019) | To investigate the influence of the Lean Start-up methodology | The results indicate that the Lean Start-up methodology positively influences the evolution of the relationship between entrepreneurs and coaches. |

| (Marullo et al. 2018) | Open Innovation as a crucial organisational factor that determines the success of a start-up. | Their work proposes eight research hypotheses that link internal resources (technology, finances, and human capital), which makes it possible for a start-up to develop financially with its initial performance, and it was concluded that these were significant. |

| (Mayer-Haug et al. 2013) | Link business talent to determine its connection to performance results. | Relevant variables proved to be experience and skills, education, planning, team size, and the internet –the way marketing and social media are used has become an important variable even when resources are lacking. |

| (O’Reilly and Binns 2019) | Illustrate how two successful companies (Amazon and IBM) have developed approaches to address innovation | Companies must master three different stages or disciplines: idea generation (ideation), incubation (validation), and growth (scaling). Successful innovation requires leaders to improve the management of these stages, especially in the scaling phase. |

| (Oukes et al. 2017) | Explore how structural and behavioural power intervenes in a start-up’s relationships with its partners. | Structural power is based on the control of resources, position in the business network, and the formal position in the business environment. The power of the start-up is mainly focused on one foundation: conciliatory tactics or power-shifting tactics, and not on the three mentioned previously. |

| (Pangarkar and Wu 2013) | A greater number of alliances, or the greater diversity of alliance partners, improves performance. | With more alliances, relationships are managed more efficiently and effectively, and performance improves. The results also suggest that companies improve their performance if their alliances are formed with diverse, rather than similar partners. |

| (Park et al. 2018) | Effect of technology and market forces on the commercial performance of SME support services. | Support services for SMEs had a direct impact on their performance. Such services also indirectly influenced the performance of SMEs by contributing to the decision-making skills of their executives |

| (Picken 2017) | To describe the essential tasks to be carried out and provide policy guidelines for the start-up. | The eight obstacles to success are the following: (1) establishing a direction and maintaining focus, (2) positioning products/services in another market, (3) maintaining a client/market focus, (4) building an organisation and management team, (5) developing effective processes and infrastructure, (6) building financial capacity, (7) developing a business culture, and (8) managing risks and vulnerabilities. |

| (Piñeiro et al. 2017) | Confirm how companies are using the Business Model Canvas. | The start-up that did not use the Business Model Canvas achieved continuous and undisrupted development, or in other words, this company performed better at the developmental level than the other two that used the Business Model Canvas. |

| (Reid et al. 2018) | Study the relationship between leadership and entrepreneurial grants. | The statistical relationship between leadership and entrepreneurship gives reliable and positive results. These two variables have thus been validated for future studies. |

| (Schou 2016) | Orientation of local government toward business initiatives; influence on the organisation and adaptation of local business policy. | Three factors were found: collaboration, adaptability and entrepreneurial orientation. The more positive the orientation of local government toward entrepreneurship, the better the adaptability of the enterprise and collaboration in the entrepreneurial support system. |

| (Sekliuckiene et al. 2018) | Understand the stages of business development. | The importance of business learning increases greatly in the start-up phase. In the seed phase, it is essential to develop social skills and use social networks, which contribute to the development of the social capital of a start-up. |

| (Serban and Roberts 2016) | Shared leadership as a mediator between the task, the team, and the results. | Meaningful and positive relationships: the value of shared leadership and how this led to high levels of quality work and overall satisfaction with its performance. |

| (Standing and Mattsson 2018) | To search for key issues and methods used in digital business development. | Leadership is an important variable. A simple, dynamic business model provides a differentiating value in a start-up (given its organic structure). |

| (St-Jean and Mathieu 2015) | Investigate the usefulness of SCCT (social cognitive career theory) in understanding the effects of mentoring. | The usefulness of SCCT in the study of business careers stands out. Furthermore, this study demonstrates the effect of business self-sufficiency on satisfaction and the intention to stay in business during career development. |

| (Sull 2004) | How start-ups and businesses deal with uncertainty while looking for opportunities. | Proper business management is shown to be a series of iterative experiments that systematically determine how much capital needs to be raised. The funds should always include an extra item for contingencies. |

| (Ucbasaran et al. 2010) | Explore whether previous business experience promotes or prevents comparative optimism in entrepreneurs. | Entrepreneurs with previous experience in one or more failed ventures are less likely than new entrepreneurs to show comparative optimism in their own businesses; however, they do show comparative optimism with regard to similar projects by other entrepreneurs. |

| Source: own elaboration. | ||

| 1 | Dave Berkus is regarded as one of the most active angel investors in the US, with holdings in more than 180 technology investments, and he currently manages Wayfare Ventures and two seed-angel venture capital funds. Berkus is the author of “Basic Berkonomics”, “Berkonomics”, “Advanced Berkonomics”, and “Extending the Runway”, the essential business literature for all early-stage targeting resources. In 2011, Berkus was named “Technology Leader of the Year” by the Los Angeles County, California Board of Supervisors, and was also named “Director of the Year, Early Stage Companies” by The Forum. for Corporate Directors for his successful leadership and CEO coaching efforts. |

| 2 | Gross is the founder of the “Idealab Incubator technology”, as well as 100 successful companies in the last 30 years. One of his greatest successes has been creating “GoTo.com”, a company that designed an innovative business model based on a search engine different from Google, but which is often linked conceptually (mainly in Silicon Valley) as the antecedent of strategies SEM (Search Engine Marketing) of Google today (Oremus 2013). |

| 3 | Payne’s (2011) Scorecard valuation method allows startups to be compared, ranking them against other recently funded companies in the same geographic region. Specifically, the Scorecard Method adjusts the estimated average value, coming from other comparable startups, to obtain the initial pre-money valuation. This method crosses this estimated market value with the success factors and their associated percentage. |

| 4 | We decided to take 2019 as the end date of the sampling period because of the disruption in business activity and academic research caused by COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. At the current date (2022) it is not possible yet to obtain a historical series of data after the pandemic that would allow a post-COVID-19 vs. Pre-COVID-19 comparison. |

| 5 | However, it is important to remember that the Idea, always is ranked in the first place in importance, both in the analysis of all the articles (60), and in the analysis by country and continent. It is only in this sample of articles based on all seven factors (25 articles) where the CEO factor gets the “top one position”. |

References

- Achimská, Veronika. 2020. Start-ups, bearers of innovation in globalizing environment and their valuation. In SHS Web of Conferences. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences, vol. 74, p. 01001. [Google Scholar]

- Akkaya, Murat. 2020. Startup valuation: Theories, models, and future. In Valuation Challenges and Solutions in Contemporary Businesses. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, Ikpe Justice. 2021. Scientometric Evaluation and Visual Analytics of the Scientific Literature Production on Entrepreneurship, Small Business Ventures, and Innovation. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 33: 717–45. [Google Scholar]

- Amis, David, Howard H. Stevenson, and Jocelyn Dinnin. 2001. Winning Angels. London: Financial Times Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Aulet, Bill. 2013. Disciplined Entrepreneurship: 24 Steps to a Successful Startup. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Aulet, William, and Fiona E. Murray. 2013. A Tale of Two Entrepreneurs: Understanding Differences in the Types of Entrepreneurship in the Economy. Kansas City: Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Joel A. C., and Brian S. Silverman. 2004. Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 411–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednár, Richard, and Natália Tarišková. 2017. Indicators of startup failure. International Scientific Journals 2: 238–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berkus, Dave. 2006. Extending the Runway: Leadership Strategies for Venture Capitalists and Executives of Funded Companies. Boston: Aspatore Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berkus, Dave. 2016. After 20 Years: Updating the Berkus Method of Valuation. Available online: https://www.angelcapitalassociation.org/blog/after-20-years-updating-the-berkus-method-of-valuation/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Booth, Andrew, Diana Papaioannou, and Anthea Sutton. 2012. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstätter, Hermann. 2011. Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Personality and Individual Differences 51: 222–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, Pearl, Barbara A. Kitchenham, David Budgen, Mark Turner, and Mohamed Khalil. 2007. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. Journal of Systems and Software 80: 571–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, Melissa S., Christopher E. Stevens, and D. Ryland Potter. 2011. Misfortunes or mistakes? Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CB Insights. 2021. Top 12 Reasons Startup Fail. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/startup-failure-reasons-top/ (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Chan, Chien Seng Richard, Pankaj C. Patel, and Phillip H. Phan. 2020. Do differences among accelerators explain differences in the performance of member ventures? Evidence from 117 accelerators in 22 countries. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 14: 224–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, Aaron, Solène Delecourt, Sarique Hasan, and Rembrand Koning. 2019. When does advice impact startup performance? Strategic Management Journal 40: 331–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jin, and Xueyan Zhu. 2008. A research on the relationship between academic entrepreneurs and enterprise performance: A three-dimension model. Frontiers of Business Research in China 2: 155–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cohen, Boyd, and Jan Kietzmann. 2014. Ride On! Mobility Business Models for the Sharing Economy. Organization & Environment 27: 279–96. [Google Scholar]

- Collewaert, Veroniek. 2012. Angel investors’ and entrepreneurs’ intentions to exit their ventures: A conflict perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36: 753–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collewaert, Veroniek. 2016. Angel–entrepreneur relationships: Demystifying their conflicts. In Handbook of Research on Business Angels. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenz, Federico, and Guido Noto. 2018. Fostering entrepreneurial learning processes through Dynamic Start-up business model simulators. The International Journal of Management Education 16: 468–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyanova, E. A. 2018. Current issues of company evaluation under fintech. Strategic Decisions and Risk Management 1: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Santamaría, Carlos, and Jacques Bulchand-Gidumal. 2021. Econometric estimation of the factors that influence startup success. Sustainability 13: 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dureux, Bruno. 2016. Cómo valora el Capital Semilla o los Business Angels, una inversión en una Startup. Revista Española de Capital Riesgo 2: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Egan-Wyer, C., Sara L. Muhr, and Alf Rehn. 2018. On startups and doublethink–resistance and conformity in negotiating the meaning of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 30: 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, Thomas R. 2013. Entrepreneurship: A Working Definition. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2013/01/what-is-entrepreneurship (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Escartín, Daniel, Àlex Marimon, Albert Rius, Xavier Vilaseca, and Àngel Vives. 2020. Cómo se valora una startup. Revista de Contabilidad y Dirección 30: 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Forliano, Canio, Paola De Bernardi, and Dorra Yahiaoui. 2021. Entrepreneurial universities: A bibliometric analysis within the business and management domains. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 165: 120522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo Molina, Virginia, Francisco Díez Martín, and Cristina Del Castillo Feito. 2022. Legitimacy in entrepreneurship. Intellectual Structure and Research Trends 22: 115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Bill. 2015. The Single Biggest Reason Why Start-Ups Succeed. [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bNpx7gpSqbY (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Hemmert, Martin, Adam R. Cross, Ying Cheng, Jae-Jin Kim, Florian Kohlbacher, Masahiro Kotosaka, Franz Waldenberger, and Leven J. Zheng. 2019. The distinctiveness and diversity of entrepreneurial ecosystems in China, Japan, and South Korea: An exploratory analysis. Asian Business & Management 18: 211–47. [Google Scholar]

- Herrador-Alcaide, Teresa, and Monserrat Hernandez-Solis. 2019. Empirical Study Regarding Non-Financial Disclosure for Social Conscious Consumption in the Spanish E-Credit Market. Sustainability 11: 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian P. T., and Sally Green, eds. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. London: The Cochrane collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, John, and Hanan F. Khazragui. 2013. Into the valley of death: Research to innovation. Drug Discovery Today 18: 610–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyytinen, Ari, Mika Pajarinen, and Petri Rouvinen. 2015. Does innovativeness reduce startup survival rates? Journal of Business Venturing 30: 564–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhwan, Aulia Dwi, and Raden Aswin Rahadi. 2022. Valuation of digital start-up business: A case study from digital payment solution services company. Eqien-Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis 10: 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kiviluoto, Niklas. 2013. Growth as evidence of firm success: Myth or reality? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25: 569–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kupp, Martin, Moira Marval, and Peter Borchers. 2017. Corporate accelerators: Fostering innovation while bringing together startups and large firms. Journal of Business Strategy 38: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, Donald F., Jeffrey S. Hornsby, and Michael G. Goldsby. 2007. The Relationship of Stakeholder Salience, Organizational Posture, and Entrepreneurial Intensity to Corporate Entrepreneurship. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 13: 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, Petteri T., Aaron F. McKenny, and Jeremy C. Short. 2019. Qualitative comparative analysis in entrepreneurship: Exploring the approach and noting opportunities for the future. In Standing on the Shoulders of Giants. Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, Sergio, and Francisco de Assis Carlos Filho. 2019. Bibliometric analysis of scientific production on sharing economy. Revista de Gestão 26: 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Hernandez, Anna K., Anabel Fernandez-Mesa, and Monica Edwards-Schachter. 2018. Team collaboration capabilities as a factor in startup success. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 14: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoori, Yashar, Tomas Karlsson, and Mats Lundqvist. 2019. The influence of the lean startup methodology on entrepreneur-coach relationships in the context of a startup accelerator. Technovation 84–85: 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marullo, Cristina, Elena Casprini, Aalberto Di Minin, and Andrea Piccaluga. 2018. Ready for Take-off: How Open Innovation influences startup success. Creativity and Innovation Management Journal 27: 476–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Haug, Katrin, Stuart Read, Jan Brinckmann, Nicholas Dew, and Dietmar Grichnik. 2013. Entrepreneurial talent and venture performance: A meta-analytic investigation of SMEs. Research Policy 42: 1251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles, and Andrew J. Binns. 2019. The Three Stages of Disruptive Innovation: Idea Generation, Incubation, and Scaling. California Management Review 61: 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, Martin, Christian Fisch, and Ryan Boyd. 2017. Using digital footprints in entrepreneurship research: A Twitter-based personality analysis of superstar entrepreneurs and managers. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 8: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremus, Will. 2013. Google’s Big Break. Slate. Available online: https://slate.com/business/2013/10/googles-big-break-how-bill-gross-goto-com-inspired-the-adwords-business-model.html (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Oukes, Tamara, Ariane Raesfeld, and Aard Groen. 2017. Power in a startup’s relationships with its established partners: Interactions between structural and behavioural power. Industrial Marketing Management 80: 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, Nitin, and Jie Wu. 2013. Alliance formation, partner diversity, and performance of Singapore startups. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 30: 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hun, Jae-Young Yoo, Seon-Hee Moon, Hyoung Yoo, Ho-Shin Lee, Tae-Hoon Kwon, and Hyuk Hahn. 2018. Effect of Technology and Market Dynamism on the Business Performances of SMEs by Supporting Services. Science, Technology and Society 24: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasayat, Ajit Kumar, Bhaskar Bhowmick, and Ritik Roy. 2020. Factors Responsible for the Success of a Start-up: A Meta-Analytic Approach. In IEEE Transactions On Engineering Management. Piscataway: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Bill. 2011. Scorecard valuation methodology. Establishing the Valuation of Prerevenue. Available online: https://seedspot.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Scorecard-Valuation-Methodology.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Phan Tan, Luc. 2021. Mapping the social entrepreneurship research: Bibliographic coupling, co-citation and co-word analyses. Cogent Business & Management 8: 1896885. [Google Scholar]

- Picken, Joseph C. 2017. From startup to scalable enterprise: Laying the foundation. Business Horizons 60: 587–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, Fabio, Janaina Mendes Oliveira, Anderson Cougo Cruz, and Tiago Zardin Patias. 2017. Business models on startups: A multicase study. Revista de Administração da UFSM 10: 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1995. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüfer, Jens, and Patricia Prüfer. 2020. Data science for entrepreneurship research: Studying demand dynamics for entrepreneurial skills in the Netherlands. Small Business Economics 55: 651–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, Andreas. 2020. Opportunities and Threats in Reviewing Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44: 847–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmus, Wiktor, and Mariola Laguna. 2018. Dimensions of entrepreneurial success: A multilevel study on stakeholders of micro-enterprises. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, Shane W., Aaron H. Anglin, John E. Baur, Jeremy C. Short, and M. Ronald Buckley. 2018. Blazing new trails or opportunity lost? Evaluating research at the intersection of leadership and entrepreneurship. The Leadership Quarterly 29: 150–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Kempis, Clariandys, Leobardo Valera, and Miguel A. Sastre-Castillo. 2021. Entrepreneurial Competence: Using Machine Learning to Classify Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 13: 8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, Margarete. 1995. Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health 18: 371–75. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, José, Jorge Inche, and David Mauricio. 2021. Critical success factors throughout the life cycle of information technology start-ups. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 8: 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, Jose Ramon, Pedro Palos-Sanchez, and Antonio Grilo. 2019. Detecting indicators for startup business success: Sentiment analysis using text data mining. Sustainability 11: 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schou, Pia Schou. 2016. Entrepreneurship Orientation in Policy Making. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 17: 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sekliuckiene, Jurgita, Rimgailė Vaitkiene, and Vestina Vainauskiene. 2018. Organisational Learning in Startup Development and International Growth. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 6: 125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, Andra, and Ashley J. B. Roberts. 2016. Exploring antecedents and outcomes of shared leadership in a creative context: A mixed-methods approach. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 181–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Liu, Zhang Kun, and Shang Jun-ru. 2022. Retrospection and prospect of embeddedness theory—Knowledge map analysis based on bibliometrics. Journal of Data, Information and Management 4: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skawińska, Eulalia, and Romuald I. Zalewski. 2020. Success Factors of Startups in the EU—A Comparative Study. Sustainability 12: 8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, Craig, and Jan Mattsson. 2018. Fake it until you make it: Business model conceptualization in digital entrepreneurship. Journal of Strategic Marketing 26: 385–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, Paul, Per Davidsson, and Jason Fitzsimmons. 2009. Performance configurations over time: Implications for growth–and profit–oriented strategies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33: 125–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, Étienne, and Cynthia Mathieu. 2015. Developing Attitudes Toward an Entrepreneurial Career Through Mentoring: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Journal of Career Development 42: 325–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, Donald N. 2004. Disciplined Entrepreneurship. MIT Sloan Management Review 46: 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tasnim, Rahayu, Salleh Yahya, and Muhammad Nizan Zainuddin. 2014. “I’m Loving It!” What Makes the Successful Entrepreneur Affectively Committed to Entrepreneurial Performance? Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship 19: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, Deniz, Paul Westhead, Mike Wright, and Manuel Flores. 2010. The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 541–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urim, Ugochukwu Moses, and David Imhonopi. 2015. Operationalising financing windows for entrepreneurship development in Nigeria: An appraisal. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting 6: 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- van Gelderen, Marco, Roy Thurik, and Niels Bosma. 2005. Success and risk factors in the pre-start-up phase. Small Business Economics 24: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacker, Tom, Veroniek Collewaert, and Ine Paeleman. 2013. The relationship between slack resources and the performance of entrepreneurial firms: The role of venture capital and angel investors. Journal of Management Studies 50: 1070–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Li, and Georgeanne M. Artz. 2019. Does rural entrepreneurship pay? Small Business Economics 53: 647–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Berkus (2016) | Weight | Gross (2015) | Weight | Payne (2011) | Weigth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Idea | 20% | Timing | 42% | Strength of the Management Team | 0–30% |

| 2 | Founding Team | 20% | Team | 32% | Size of the Opportunity (scalability) | 0–25% |

| 3 | Functional Prototype | 20% | Idea | 28% | Product/Technology | 0–15% |

| 4 | Strategic Relations | 20% | Business Model | 24% | Competitive Environment | 0–10% |

| 5 | Traction or Turnover | 20% | Funding | 14% | Marketing/Sales Channels/Partnerships | 0–10% |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | Need for Additional Investment | 0–5% |

| 7 | - | - | - | - | Other | 0–5% |

| Factor of Study | Synonyms or Variables Found in the Articles Analysed |

|---|---|

| Timing | Timing, Startup Stages, Time, Moment, Opportunity |

| Team | Team, Collaboration, Cohesion, Teamwork, Cohesity |

| Idea | Idea, Innovation, Value, Product |

| Business Model | Business Model, Profit, Economic Model, Control, Business Plan |

| Funding | Financing, Financial Variables, Finance, Money, Funding, Funds |

| Ceo Decisions | CEO Decisions, Leadership, Ambiguity, Decision Making, Power, Management |

| Marketing | Marketing, Communication, Business Intelligence, Advertisement, Social Networks, Publicity |

| Culture of Evaluation | Evaluation, KPI, Constant Evaluation, Monitoring, Continuous Monitoring |

| Culture/Values | Cultural alignment, Values Alignment, Communication Strategy, |

| Dynamic Adaptation | Dynamic Adaptation, Stress, Speed, Dynamic capabilities, Reinvent, Vanguard |

| Satisfaction | Satisfaction, Fun, Optimism, Wellbeing |

| Training And Development | Training, Mentoring, |

| Diversity | Diversity, Mentality, Heterogeneity, Horizontal system |

| Advisors | Board, Advisors, Steering Committee |

| Lean Startup | Lean startup, Going lean, Prototype, Split testing, Continuous deployment |

| Founders Experience | Founder’s Experience, Founder, Founders |

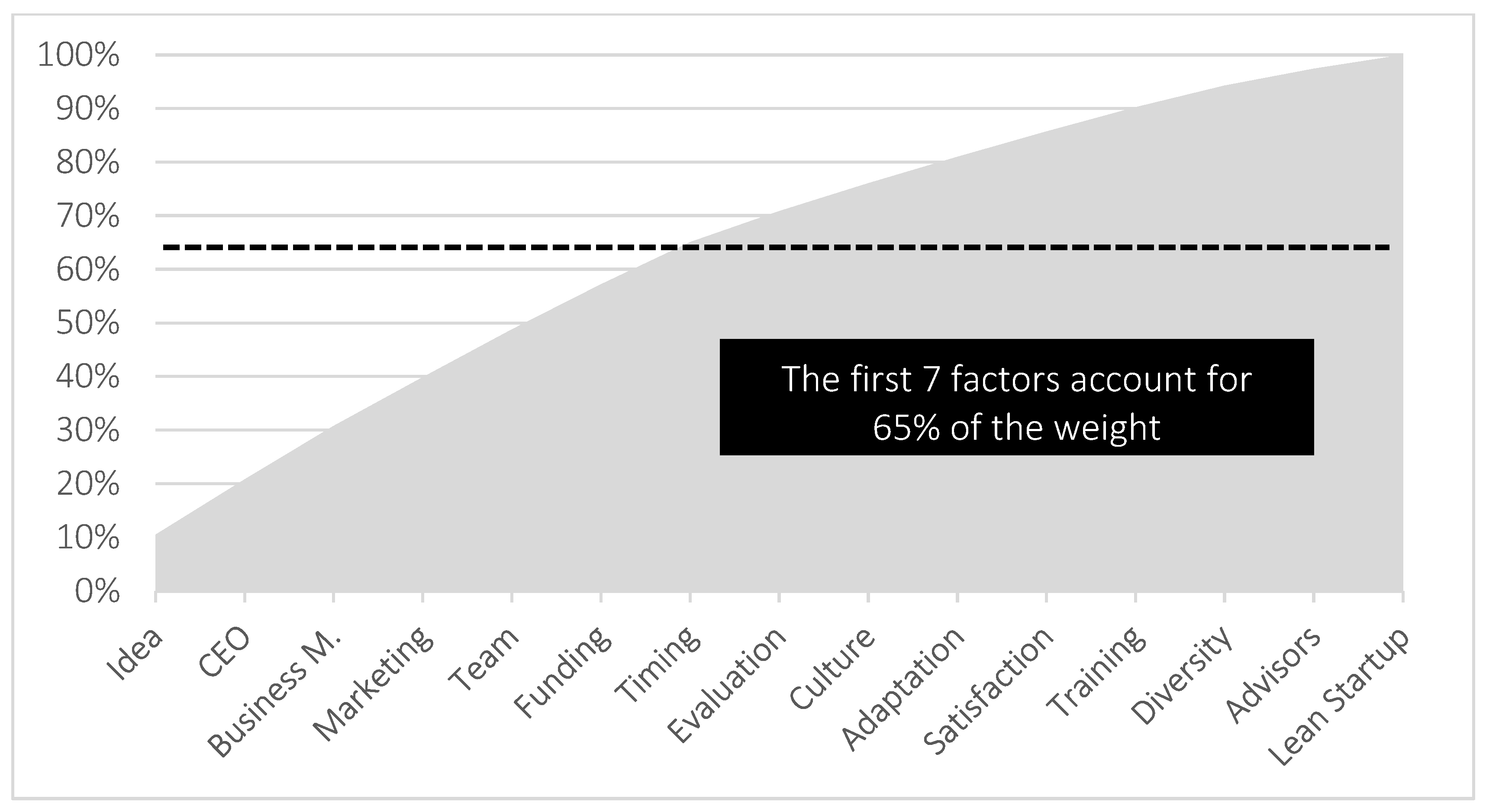

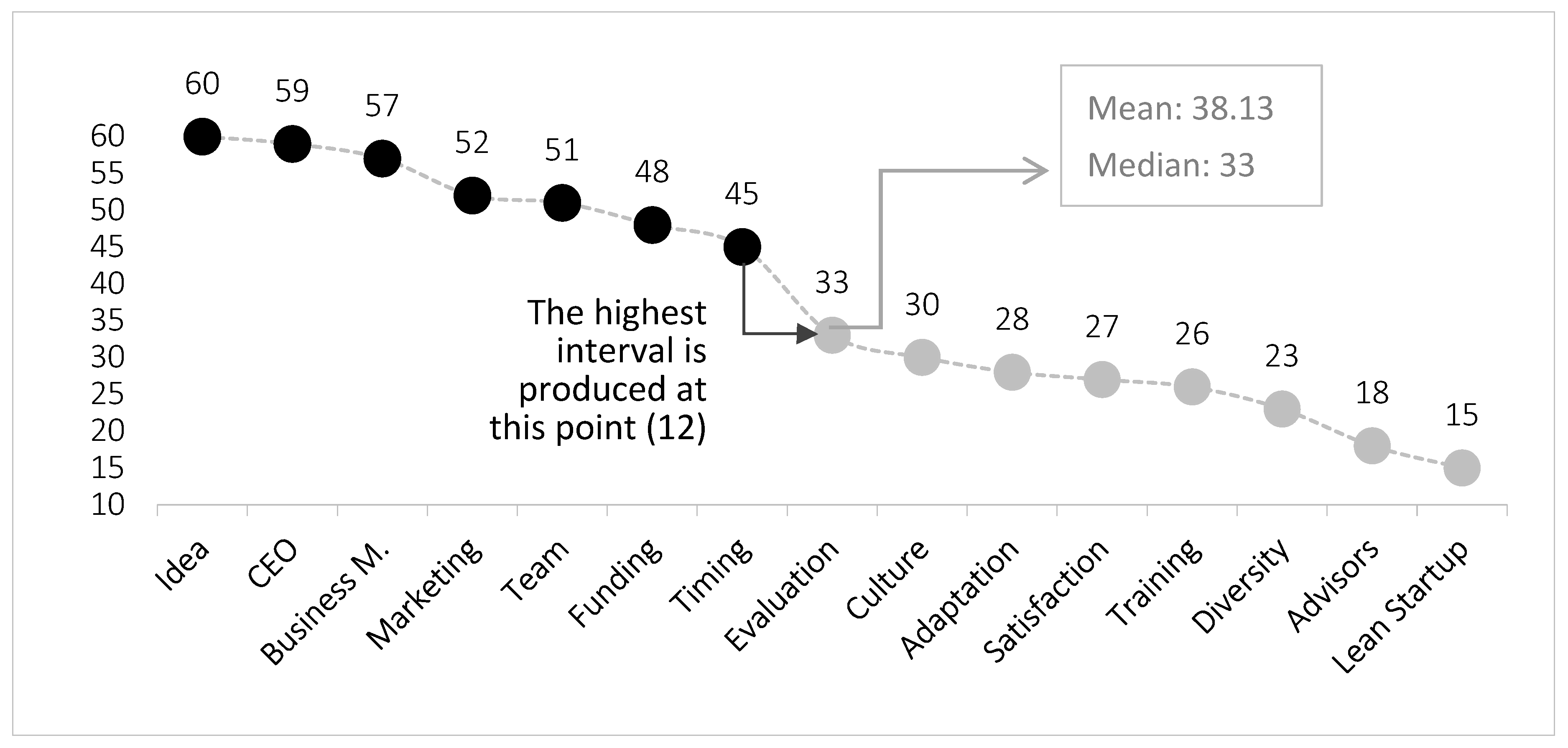

| Ranking | Factor | Absolute Number of Appearances in Articles | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Idea | 60 | 10.5% | 10.5% |

| 2 | CEO decisions | 59 | 10.3% | 20.8% |

| 3 | Business model | 57 | 10.0% | 30.8% |

| 4 | Marketing | 52 | 9.1% | 39.9% |

| 5 | Team | 51 | 8.9% | 48.8% |

| 6 | Funding | 48 | 8.4% | 57.2% |

| 7 | Timing | 45 | 7.9% | 65.0% |

| 8 | Evaluation culture | 33 | 5.8% | 70.8% |

| 9 | Culture and values | 30 | 5.2% | 76.0% |

| 10 | Adaptation to the environment | 28 | 4.9% | 80.9% |

| 11 | Satisfaction | 27 | 4.7% | 85.7% |

| 12 | Training | 26 | 4.5% | 90.2% |

| 13 | Diversity | 23 | 4.0% | 94.2% |

| 14 | Advisors | 18 | 3.1% | 97.4% |

| 15 | Lean Start-up | 15 | 2.6% | 100.0% |

| 572 | 100% |

| Country | Number of Articles | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| The United States | 18 | 30% |

| England | 4 | 7% |

| The Netherlands | 4 | 7% |

| Italy | 3 | 5% |

| Canada | 3 | 5% |

| Brazil | 3 | 5% |

| Singapore | 2 | 3% |

| South Korea | 2 | 3% |

| France | 2 | 3% |

| Spain | 2 | 3% |

| TOTAL (of 60 articles) | 72% | |

| Number of Factors Found | Articles |

|---|---|

| 7 | 25 |

| 6 | 24 |

| 5 | 9 |

| 4 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 60 |

| Total Results | Weight | North America | Weight | Europe | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Idea | 10.5% | Idea | 10.6% | Idea | 10.3% |

| 2 | CEO Decisions | 10.3% | CEO Decisions | 10.6% | Business Model | 10.3% |

| 3 | Business Model | 10.0% | Business Model | 9.5% | CEO Decisions | 9.8% |

| 4 | Marketing | 9.1% | Marketing | 9.0% | Team | 9.4% |

| 5 | Team | 8.9% | Team | 8.5% | Marketing | 8.5% |

| 6 | Funding | 8.4% | Funding | 8.5% | Funding | 8.0% |

| 7 | Timing | 7.9% | Timing | 6.0% | Timing | 8.0% |

| TOTAL | 65.1% | TOTAL | 63.3% | TOTAL | 64.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sevilla-Bernardo, J.; Sanchez-Robles, B.; Herrador-Alcaide, T.C. Success Factors of Startups in Research Literature within the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030102

Sevilla-Bernardo J, Sanchez-Robles B, Herrador-Alcaide TC. Success Factors of Startups in Research Literature within the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleSevilla-Bernardo, Javier, Blanca Sanchez-Robles, and Teresa C. Herrador-Alcaide. 2022. "Success Factors of Startups in Research Literature within the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030102

APA StyleSevilla-Bernardo, J., Sanchez-Robles, B., & Herrador-Alcaide, T. C. (2022). Success Factors of Startups in Research Literature within the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030102