Abstract

Recent research on management control and performance measurement and management (PMM) points towards a concern to provide suitable systems in nonprofit organizations (NPOs). However, few attempts have been made to understand these organizations and how their peculiarities influence this process. This research empirically discusses NPOs’ features through the lens of performance measurement and how these features influence performance measurement system’ design, the first step for an iterative PMM. A case study with two NPOs in the United States of America and Brazil provides valuable insights into the design factors. Results indicate that various factors related to purpose, stakeholders, and management influence the design of the performance-measurement system. Their unique organizational characteristics impact the usability and viability of the application of performance-measurement systems.

1. Introduction

Despite the existence of unlimited nonprofit organizations (NPOs) in diverse contexts worldwide, they all resemble aspects of pursuing social value creation for their clients/beneficiaries. In recent years, these organizations have come under pressure to improve their management practices, efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability. They have sought to optimize their performance with cost reductions, better allocation of available resources, workforce motivation and involved people, volunteering, better communication channels with stakeholders, and better operations and services management practices (Popovich 1998; Berman 2014; Sinuany-Stern and Sherman 2014).

Many studies conduct initial investigations of performance measurement and management (PMM) in NPOs; see Cestari et al. (2021), Treinta et al. (2020), Moura et al. (2020), Maran et al. (2018), Cestari et al. (2018), Soysa et al. (2018), Leotta and Ruggeri (2017), Bracci et al. (2017), Moura et al. (2016), Schwartz and Deber (2016), Lee and Nowell (2015), Balabonienė and Večerskienė (2015), and Mouchamps (2014). In a recent systematic literature review (SLR) led to study the factors that influence the design of performance measurement systems (PMSs) in NPOs, it was found that there have been 240 articles published on this topic were between 1985 and 2015, with the majority of them (220 articles) having been published since 2001 (Moura et al. 2019). Despite this growth, the research area is not yet mature, and there is no representative author associated with the topic. From the total of 525 authors of those 240 articles, only 33 published two or more articles, with 94% of the authors authoring only one paper.

Different performance-measurement (PM) frameworks have been developed and documented in the literature. However, which framework best fits each particular organization? Some researchers argue that the frameworks developed for for-profit enterprises do not work in such companies as NPOs and public administration (PA). Despite their differences in terms of management and sources of income, it is possible to argue that they both pursue social profit before financial profit (Cestari et al. 2021; Munik et al. 2021; Treinta et al. 2020; Moura et al. 2019, 2020). Micheli and Kennerley (2005) argue that the Performance Prism, which focuses on a stakeholder perspective, has limited application for both NPOs and the PA. Raus et al. (2010) argue that the Social Return on Investments (SROI), derived from the well-known Return on Investments (ROI) concept, considers the social, financial, and economic value, but not the operational and strategic value. According to a study about the use of PMSs for social enterprises by Mouchamps (2014), the SROI, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) do not present enough features to meet all organizational characteristics necessary for a complete framework. Felício et al. (2021) examine the application of Management Control Systems (MCSs) in the public sector as there is a gap in the literature considering its relevance in private and nonprofit sectors. The study developed by Reda (2017) with higher education institutions indicates that the BSC does not capture the core organizational functions. There was a low sensitivity of the system to the efforts in quality assurance procedures. In the study about BSC in local government organizations by Northcott and Taulapapa (2012), some managers reported difficulties using the BSC even after adapting its dimensions to their context. This statement can indicate the lack of specific leadership and governance perspectives and the difficulty of translating key elements of the framework (measures, inputs, outputs, and outcomes) to the public sector context.

On the other hand, other studies show PM frameworks and systems implementations in NPOs. Although many authors suggest that an NPO has unique characteristics compared to the private sector, Moxham (2009) challenges this understanding and argues that the essence of the frameworks developed for them can be applied in the NPO context. Her findings suggest that the same drivers to use a PMS in the private sector are present in the NPO context: financial reporting, demonstration of achievements, operational control, and facilitation of continuous improvement. “The key difference was that the criteria used to measure non-profit performance were seldom linked to performance improvement; this is contrary to the practices advocated in the private and public sector literature” (Moxham 2009, p. 755). In an SLR performed by the author about third sector PMSs, three drivers emerged: accountability, legitimacy, and improvement of efficiency and effectiveness (Moxham 2014). DeBusk et al. (2003) conclude that the definition of performance indicators is situational, i.e., the organizational strategy affects the PM design. In this context, nonfinancial measures can be significantly more relevant for some organizations than others, focusing on the social approach.

Based on these perspectives, this paper aims to discuss the features of the NPOs through a PM lens and how these features influence the design of their PMSs. For that, the paper intends to provide insights related to the following research question:

What role do design factors play in applying performance measurement systems in nonprofit organizations?

This paper presents a case study with two NPOs from Brazil and the United States of America (USA) to test and discuss the relevance and applicability of the factors for managers, academics, and practitioners in designing PMSs for such organizations. For that, the analysis is performed through the lens of a set of 10 design factors present in Moura et al.’s (2019, 2020) research, offering an opportunity for a better comprehension of multiple and complex issues.

2. Theoretical Background

Management control is a critical issue in any kind of business routine. As explained by Merchant and Van der Stede (2007, p. 3), “management control failures can lead to large financial losses, reputation damage, and possibly even organizational failure”. Control is one step of the management process, including objective setting, financial and nonfinancial, strategy formulation, and management control. According to the authors, one huge problem in the area of NPO management is measuring and rewarding performance, because their social nature does not provide explicit quantifiable measures.

PMM systems offer organizations ways to translate the strategy into measurable terms. The two components of a PMM, i.e., measurement and management, need to be designed to reach the strategy and support decision making. Performance management refers to a system that works through the PM to manage organizational performance (Bititci 2015). Once the PM is the input for control, PMSs address the strategy and results and support performance management (de Lima et al. 2013).

In this way, it is crucial to delimitate what characterizes a PMS in this study. Once the PM is difficult for the NPOs (Merchant and Van der Stede 2007), understanding their particularities and features will support the PMM design and implementation process (Treinta et al. 2020). As cited before, there is no consensus about the usability of the frameworks designed for traditional for-profit organizations despite their advancement and use by many organizations, large and small (Munik et al. 2016; Moura et al. 2019; Anonymous 2020; Cestari et al. 2021). According to Hoque (2014), the most studied PMS is the BSC, presenting four perspectives: financial, customer, internal business, and learning and growth (Kaplan and Norton 1992, 1996; Inamdar et al. 2000). The BSC is adopted or adapted for some NPOs (Kaplan 2001), putting the customer and mission’s role at the top of the perspectives. One of the ratios used to measure the social impact, the SROI, “is a mixed method approach to assess the social, economic, and environmental impact of intervention” (Maier et al. 2015). The Performance Prism proposes “a second generation measurement framework designed to assist performance measurement selection […] that addresses the key business issues to which a wide variety of organisations, profit and not-for-profit, will be able to relate” (Neely et al. 2001, p. 6). This model works with five interrelated facets: stakeholder satisfaction, strategies, processes, capabilities, and stakeholder contribution.

Indeed, many studies show that the adaptations of PMSs were not enough to capture all particularities that involve the NPO even after adaptations (Micheli and Kennerley 2005; Northcott and Taulapapa 2012; Mouchamps 2014; Moura et al. 2016; Munik et al. 2021). An SLR and content analysis previously conducted with the target to identify the factors that influence the design of a PMS in NPO and PA shows that these organizations present particular characteristics that impact the applicability and usability of the current PMSs (see Moura et al. 2019, 2020). The outputs indicate a set of 10 factors distributed between three groups (purpose, stakeholders, and management) that can influence the design of PMSs for those organizations. Table 1 shows the design factors and their description.

Table 1.

Factors that influence the design of PMSs in NPO and PA.

From these factors, it is possible to note that both NPOs and PAs have unique characteristics compared with for-profit enterprises that may impact the current PMSs’ usability, e.g., the social approach more than the financial profit and the accountability process (Cestari et al. 2021; Munik et al. 2021; Treinta et al. 2020; Moura et al. 2019, 2020; Micheli and Kennerley 2005). It is also possible to capture some reasons for understanding why some managers look with certain skepticism and resistance to use those systems in the context of social goals. Once the measurement and the performance management work in an interactive process, it is crucial that the PMS contribute and impact the strategy reach, looking at the organization.

This paper presents a case study with two NPOs to test this set of 10 factors identified through the SLR and content analysis and discuss their relevance and applicability as a practical guideline to managers, academic researchers, and practitioners in the design process of PMS to NPOs.

3. Research Design, Materials, and Methods

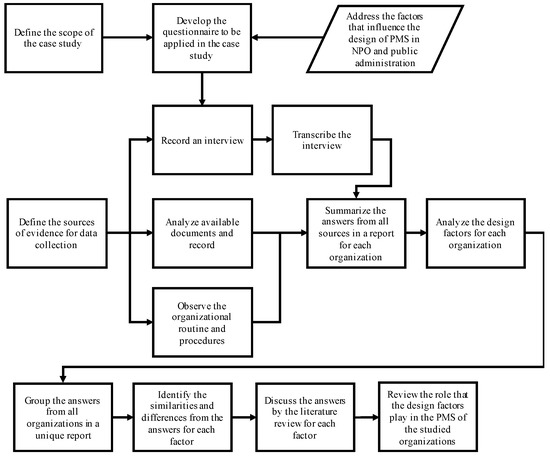

A case study approach identifies and reviews the role of design factors in the studied nonprofit organizations’ PMSs. The case study allows the researcher to learn deeply about a subject, as explained by Barratt et al. (2011). Figure 1 shows the summarized steps of the protocol followed by its description.

Figure 1.

Case study protocol.

Define the scope of the case study. Participating organizations (or a subunit within a larger organization) can represent any location, sector, or organizational size should be nonprofit or public. It should have implemented a new/redesigned PMS.

Develop the questionnaire to be applied in the case study. Based on the 10 factors (see Appendix A Table A1), a questionnaire is performed to support the understanding of each factor in the organization’s context.

Define the sources of evidence for data collection; record an interview; transcribe the interview; analyze available documents and records; observe the organizational routine and procedures. For each participating organization, an individual interview with personnel involved with the performance measurement system, producing data for performance measures, producing performance reports, or reviewing information from performance measures, was carried out and transcribed. Moreover, the protocol collects evidence from documents, records, and observations to ensure the validity of the data.

Summarize the answers from all sources in a report for each organization. The responses from the interview using the questionnaire were triangulated with the data from other sources, such as websites, annual reports, and spreadsheets, when applicable. The summarized answers facilitate the analysis and report.

Group the answers from all organizations in a unique report; identify the similarities and differences from the answers for each factor. Each analyzed factor grouped all answers. An analysis of the answers identifies the similarities and differences in the influence of the factors among the organizations.

Identify the similarities and differences from the answers for each factor. An analysis of the answers was conducted to identify the similarities and differences in the influence of the factors among the organizations.

Discuss the answers by the literature review for each factor. After summarizing all the answers and identifying similarities and differences, a discussion based on the literature review is presented.

Review the role that the design factors play in the PMS of the studied organizations. This step answers the research question: What role do the design factors play in some applications of PMS in non-profit and public organizations? The results indicate that the factors play in different ways in the studied organizations, suggesting that a factor can influence the design of the PMS in other levels. Moreover, the protocol points out that some factors are present in the organization’s routine but, in some cases, are not being adequately studied or considered, which disrupts the development of a holistic system.

Two NPOs from two countries participated in the case study, selected using the following criteria:

- -

- Prioritize the social mission;

- -

- Use the PM for making decision;

- -

- Should have implemented a new/redesigned PMS.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the organizations’ overview and analyzes the design factors based on the questionnaire to answer the role the design factors play in the PMS in the studied NPOs.

4.1. Overview of the Organizations

A case study with two NPOs in the United States of America and Brazil provides valuable insights into the design factors. Table 2 presents a brief of the details of each organization in this study. Organizations are identified as US (United States) and BR (Brazil).

Table 2.

Overview of the studied organizations.

No organization has only one funding mechanism, but one source usually is the most relevant. The NPOs work based on projects and only the US.NPO.1 works with volunteers in the secondary activities.

The NPOs are research institutes and development, and their primary source of income is from their sponsors and contracts, and, in some cases, they are eligible for government subsidies.

4.2. Main Outputs and Discussion

This section analyses each design factor discussing their role in the studied organizations. The PMSs do not focus on all factors supporting the legitimacy or the strategic management control. Those organizations’ routine indicates that they influence the management and their activities through the PM. Besides that, the interviewers tend to admit their relevance and concern for future management reviews.

The findings in the case study suggest that no PMS is mature enough to consider all factors. It is possible to argue that, sometimes, a factor could not be significant in the design process, e.g., volunteering and fairness. However, this decision depends on assessing the pertinence or not to the organizational routine, particularly if a new feature or indicator can help toward legal obligations, trust, management control, or satisfaction.

- What role does the “social approach” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

In this study, both NPOs show that social value and social impact are not adequately measured, despite the literature pointing out that such measures are important to get more investments, attract new investors or donors, and improve legitimacy. However, the literature also indicates how difficult it is to define measures to social aspects. There is difficulty gathering community interests because of the high cost for that or by management interests to provide efforts for that, as Moura et al. (2019) indicated.

The social approach is reflected in their mission, focusing on social goals, social value creation, and social impact to prove their effectiveness and legitimacy.

Stakeholders want to know if their resources are being well invested, so demonstrating achievement and the social mission reflected in the value creation are important ways to create legitimacy. However, usually, their performance measures only address external and legal requirements. If an NPO does not provide information about the mission achieved, only financial or efficiency measures can depreciate the actual social value creation considering intangible aspects, e.g., poverty reduction, education improvement, and quality of life. For that, a PMS with a holistic perspective could assess intangible results and performance management. According to Jones (2014, p. 120), “organisation collect a variety of data to funders but fail to allot time to synthesise and discuss the data they collect”. Without a mission-oriented design, the PM misses much data to reach credibility and trust and obtain new funders and donors. In this way, the social mission definition is crucial. The more abstract and general the mission definitions are, the higher the complexity in elaborating the measures and related goals.

- What role does “accountability” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

Both NPOs point out the practice of accountability with the PMS providing information and attending to external stakeholders’ requirements.

In this sense, communicating organizational data to external stakeholders can accomplish a legal obligation and increase the credibility and trust of the community and sponsors or donors for NPOs (Yang and Northcott 2018). Nevertheless, communicating performance advances and social outcomes after investments, grants, subsidies, or donations can be a challenge in the long term, but more yet, in the short term (Mauro et al. 2019). It is worth mentioning that some funders and donors recognize that information about social aspects is more important than financial data only. Hence, accountability is an alternative to providing legal reports and measures that enhance legitimacy (Cordery and Sinclair 2013; Moxham 2014). Besides, external and internal accounting can support the organizational success once the stakeholders, especially the internal ones, can perceive their roles and outcomes (Daff and Parker 2021).

The development of methods and procedures can combine PM and accountability. Some organizations have to readjust their system to execute devices to accomplish internal controls and legal obligations. Besides that, NPOs can practice constructive and voluntary accountability through the reports to bring new funding and maintain current funders (Connolly and Kelly 2011).

- What role does the “legitimacy” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

Although none of the organizations in this study uses the PMS to support the process of legitimization, the literature points out how its use can be helpful as a mechanism to increase legitimacy, contributing to organizational promotion, attracting new funders and investments, or maintaining the credibility and confidence of the population. Since these organizations recognize the importance of legitimacy and how a PMS can contribute, improving its characteristics can be an essential feature in its design.

The study performed by Hyndman and McConville (2018) argues how significant is the interaction between accountability and trust to reinforce each one. Their analysis shows the stakeholders’ requirements related to information needs, consequently influencing the organizational routine and public trust. This interaction is present in the study performed by Moura et al. (2020). The authors developed a centrality degree analysis. Accountability is highly related to the organizational’ social approach, stakeholders” involvement, and legitimacy. In this way, “stakeholders can influence social characteristics in the definition of organizational goals, in how to measure social impact and social value, and in the consideration of community interests” (Moura et al. 2020, p. 390).

Besides the legitimacy seen as a perception by stakeholders, Shuman (1995) explains legitimacy as an organization-promotion strategy. Performance reporting, financial reporting, accountability (voluntary or not), and achievement can promote an organization. Many organizations use this reporting and results of social impact such as a strategy to attract more funders, new donors, volunteers or maintain the actuals, to assure credibility and to provide legitimacy to stakeholders (Clark and Brennan 2012; Cordery and Sinclair 2013; Arvidson and Lyon 2014). Even public organizations can seek legitimacy to improve and strengthen their opinion by citizens. In this sense, performance reporting can contribute to organizational promotion more than financial reporting (Cordery and Sinclair 2013).

According to Crucke and Decramer (2016) and Moxham (2014), some NPOs use the PMS only to legitimize their activities. Conrad and Uslu (2012) emphasize that political interests may compromise PM’s definition to achieve an expected level of legitimacy in PA, leading to inappropriate targets or consequences that may cause difficulties for the efficiency and effectiveness of management and the public service. So, to legitimize operations through reports and performance indicators, the PMS should be designed for this purpose.

- What role does “volunteering” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

Although not widely studied, volunteering is present in one NPO. None of the organizations surveyed in this research provides a PMS that evaluates volunteers. However, the literature shows that people have different expectations when working voluntarily, and although not paid, motivations and benefits can attract and value them (Moura et al. 2019, 2020).

Human resources to NPOs can be composed of employees and volunteers. Not all NPOs or public sectors have volunteer staff, but some of them heavily rely on volunteers, such as welfare services and humanitarian aid. They can be an attractive alternative to accomplishing tasks, mainly when resources are limited and financial restrictions to payments are imposed. Thus, an organization needs to know how to manage their motivation, available activities, and life satisfaction from the recruitment to the evaluation and rewards (Cnaan and Cascio 1998; Duque-Zuluaga and Schneider 2008). Moreover, Jevanesan et al. (2021) study the importance of improved staff empowerment in the voluntary sector, but how can a voluntary organization measure staff performance?

Despite their different expectations, volunteer staff should be in the PM routine. In this way, volunteering is a strategical tool for organizational management in the PMS context of an NPO. The study of Navimipour et al. (2018) points out that information technology, corporate culture, and employees’ satisfaction play essential roles in enhancing the organizations’ performance. In this way, employed or volunteering workers influence the organizational culture as they shall be considered performance management.

Social services can be labor-intensive, which can interfere with employees’ volunteer motivation. Monetizing volunteers can be complex and a barrier to maintaining them (Cordery and Sinclair 2013). As employees’ participation in organizational process development, volunteers can be included equally (Duque-Zuluaga and Schneider 2008; Taylor and Taylor 2014).

- What role does the “involvement and influence of stakeholders” play in PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

The studied organizations show that stakeholders’ involvement and requirements can affect the PM and management in different ways, such as governmental and political issues, legal obligations, or contractual aspects. Kale’s (2019) study discusses the challenge of managing stakeholders in the context of medical device regulation. It identifies contestation, conflict, and coalitions as a critical mechanism through which different stakeholders influence, enable or disable institutional change. In this way, countries struggling with the development of healthcare technology regulatory policy face a challenging perspective to manage stakeholders—private, nonprofit, and public organizations partnerships, focusing on appropriate local societal context and needs.

It is hard to meet accountability and PM requirements for many stakeholders of varied characteristics and interests (Taylor and Taylor 2014; Wellens and Jegers 2014; Pirozzi and Ferulano 2016; Hyndman and McConville 2018; Moura et al. 2019, 2020). So, it is possible to analyze the stakeholders by their influence and involvement in the NPO context.

The difference between stakeholders’ influence and involvement demands a distinctive performance assessment framework and performance measures to be monitored and reported (Amado and dos Santos 2009; Conaty 2012; Cordery and Sinclair 2013). There is increasing pressure for social-mission companies to use practical management tools (Grigoroudis et al. 2012). Still, sometimes these organizations, especially the third sector, have demands imposed by funders, not themselves (Cordery and Sinclair 2013).

Political and governmental interests, funders, regulatory agencies, public sector commissioners, and legislative bodies may influence the measurement criteria both positively and negatively, requiring different targets or some forms of social impact measurement (Conrad and Uslu 2012; Cordery and Sinclair 2013; Arvidson and Lyon 2014). Liguori and Steccolini (2018) argue how significant the involvement and influence of stakeholders are in public interests in the context of public-sector accounting reforms. The study of Hyndman and McConville (2018) identifies the use of a wide range of mechanisms to respond to stakeholders’ requirements as critical and as a potential creator of a virtuous circle between accountability and public trust.

- What role does “financial sustainability” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

All organizations in this study manage their finances from alternative sources of income. However, almost all of them cannot control them individually and acquire performance indicators according to investments, donations, or other sources that could help in the accountability and legitimacy process. Additionally, managing their finances is essential for their financial sustainability, which external variables can significantly influence political issues.

Financial sustainability through alternative sources of income is a challenging and critical dimension to be managed. NPOs usually combine alternative sources of income such as donations, subsidies, volunteering, public funders, philanthropic funders, and, when legally possible, sales of products or services (Cordery and Sinclair 2013; Taylor and Taylor 2014; Arena et al. 2015).

NPOs’ characteristics include legal and financial restrictions, depending on donors, findings, or subsidies (Daff and Parker 2021). This dependence on resources can determine organizational survival. Resources help an organization establish a capacity that delivers public services (Dobmeyer et al. 2002), so governmental divergences and tax support directly impact any NPO (Kong 2010).

Some organizations have a collaborative partnership with companies to reach social responsibility improvement (Kong 2010). Because of legislation, resource providers do not have financial profit (Cordery and Sinclair 2013). These economic characteristics involve a good NPO strategy for obtaining resources (Duque-Zuluaga and Schneider 2008). The study of Henderson and Lambert (2018) discusses the influence of funders imposing frameworks and performance measures. Sometimes, those requirements can move away from the social mission due to the financial outputs. In this way, there is a challenge for some nonprofit organizations to maintain their social mission as the central aim even when their financial circumstances are difficult.

The dependence on alternative sources of income has increased the practice of PMM (Cordery and Sinclair 2013). Usually, funders, donors, investors, governments, and regulatory bodies want to know how efficient financial resources management is. In this way, a PMS must include information for the stakeholders, delivering consistent reports to them (Moura et al. 2019, 2020), potentially improving the continuous improvement process (Jevanesan et al. 2021) and balancing the social mission and money (Henderson and Lambert 2018).

- What role does the “short and long-term planning” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

The studied organizations work with complex issues related to the short and long-term. The planning can be affected by political or budget problems, and the measurement of long-term aspects can be critical.

The literature points out that NPO planning is affected by many variables, including availability and limitation of resources (human, financial, and materials), alternative sources of income, stakeholders’ interests, political interests, and social demands (Kong 2010; McEwen et al. 2010; Arena et al. 2015; Mehrotra and Verma 2015; Moura et al. 2019, 2020).

Short-term planning is due to time-limited grants and subsidies, contracts to investments, uncertainty, and insecure donations from people and companies (Taylor and Taylor 2014). This is a challenge to manage because the social impact can be seen only long-term (Moxham 2009; Kong 2010; Valentinov 2011).

- What role does “fairness” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

None of the organizations in this study must work fairly; although they have this awareness, no performance indicator is available to validate measurable terms.

Fairness or interlocal equity is a challenge to any social-mission business. Interlocal equity means providing equitable social results and homogenous service levels to beneficiaries or communities throughout the same neighbourhood, area, state, or country (Moura et al. 2019, 2020). Interlocal equity provides equitable social results and homogenous service levels to beneficiaries throughout the same neighbourhood, area, state, or country. In the social enterprise context, for example, Arena et al. (2015) indicate fairness as a capacity of the organization to ensure products or services for the whole society.

Measurement of interlocal equity horizontally involves “the ability to develop comprehensive and integrated policy solutions on the local level” (Ebinger et al. 2011, p. 562). Organizational capacity is necessary to produce outcomes and maintain high efficiency and effectiveness (Karwan and Markland 2006; Ebinger et al. 2011).

- What role does the “efficiency and effectiveness” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

While the organizations conduct the efficiency index very well, the effectiveness is not evaluated. Indeed, the definition of efficiency and effectiveness measures in the social context of social-mission companies is challenging. Intangible measures and results are complex issues to be managed and reported. Moreover, the PMS’s use can be problematic if its use is not very well defined, and the people, sometimes, may look at it as a competition or a way to assess personal aspects. Despite this, all organizations in this study have a PMS contributing to the monitoring and developing performance reports.

Measuring performance in an NPO is not a quickly answered question because the criteria are not well defined in the literature (Moura et al. 2019, 2020). Moreover, usually, the NPOs do not have financial resources to make information technology investments or realize data collection and analysis (Arena et al. 2015). In the same way, Kumar et al. (2021) argue that some services in countries under high government control face many barriers to adopting technologies to improve their system’s effectiveness and transparency.

PMSs have to be integrated into the routine activities of an organization. Performance data and reporting have to be synchronized among organizational levels. Management reporting or performance reporting, for example, is required to be transparent about resources, activities, and governance by stakeholders (Ebrahim and Rangan 2014), as well as to auditors and evaluators, especially by regulatory agencies, donors, and community (Moxham 2009). Internally, these same reports can contribute to the organizational evaluation, operational control, and resources management (Dobmeyer et al. 2002).

- What role does the “strategic management control” play in the PMSs applications in the studied NPOs?

The PM is an essential step for performance management and will support the planning, control, and decision making. The literature also points out that using a PMS can be a strategic tool to improve learning and continuous improvement (Moura et al. 2019, 2020). However, the organizations in this study do not use the PMS properly once the PMS provides this function, but it is not available for all organization levels.

Strategic management control refers to the organizational management involving the ability to learn and continuous improvement, and, in this way, the PMS can be a tool to reach it. Crucke and Decramer (2016, p. 3) explain, “a performance measurement tool can be used as an internal management instrument, enabling organisations to assess their performance and support internal decision-making”. Noordin et al. (2017, p. 925) argues that “an effective PMS serves as a platform for organisations not just to discharge their accountability but also to facilitate their management and internal control activities”. Nguyen et al. (2015) also explain that a PMS can support the learning and evaluate the strategy to achieve the mission. Jevanesan et al. (2021) point out that the appropriate leadership, organizational culture, and staff engagement are critical success factors toward implementing any continuous improvement method.

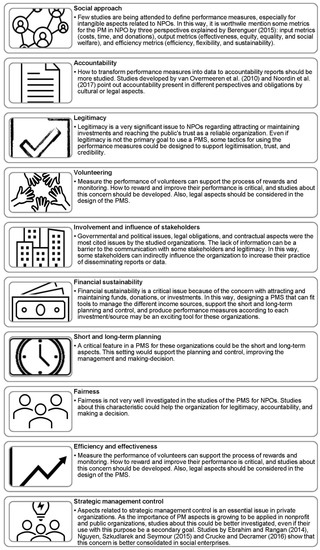

4.3. Concerns, Insights, and Future Research Issues

The performed case study with those two NPOs points out the relevance of advances on the research agenda of PMS. Each design factor in their practice is analysed through the lens of theoretical and empirical aspects contributing to a better understanding of the factors and providing insights and future research. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Concerns, insights, and future research issues.

This variability can result from the organization’s size and efforts to measure the performance and provide human. Furthermore, financial resources and the importance of using the PMS as a tool, essential aspects as accountability, and managerial aspects as the strategic management control contribute to employees’ and volunteers’ organizational mood and rewards.

5. Conclusions

This paper discusses the features of the NPOs through PM’s lens and how these features influence the design of the PMS for them. A set of factors related to purpose, stakeholders, and management supports the case study in two NPOs, forwarding the knowledge about the factors that can influence the design of a PMS in the context of an NPO. In this way, it is possible to answer the research question: “What role do design factors play in applying performance measurement systems in non-profit organizations?”

The case study introduces how the design factors can influence different ways. The applicability of one factor can vary according to the external and internal aspects and influences. The results suggest that the set of factors should be considered as recommendations for the PMS’s design. In this way, the managers, practitioners, and researchers must evaluate each factor considering the operational characteristics, the legal obligations, the organizational culture, and mainly, the organizational strategy focusing on the PMS as a component of the iterative process PMM.

The literature suggests that adopting the traditional PMS was not acceptable for many NPOs. See Northcott and Taulapapa (2012); Leotta and Ruggeri (2017); Reda (2017); Moura et al. (2019, 2020); Cestari et al. (2021). The case study attests that these organizations present distinctive characteristics such as financial sustainability when it involves alternative sources of income and legal restrictions in using the resources.

A limitation of this study is getting an NPO participation that uses a PMS. Some do not consider the PMS a helpful tool or do not have financial resources to design or implement it or have enough human resources to provide efforts.

Despite the skepticism of PMS adoptions from the private sector or adaptations, as future research, the set of factors can be used as a guideline or criteria to assess the dimensions of those PMSs. Once the set of factors is reflected in its design and corresponds to the organizational characteristics, the PMS’s use could be considered beneficial and applicable to the management control. Moreover, the design factors and concerns, insights, and future research issues can support managers, practitioners, and researchers to design, redesign, assess, and support the implementation of PMS. It is not easy to meet a mindset of guidelines or recommendations in the design process. So, this research can progress the PM in terms of theoretical and practical issues.

Some topics need more attention in the study about PM. More research about volunteering and how to measure the performance of and provide rewards for volunteers should be engaging. Besides that, once some NPOs work to provide services that the public sector cannot always do, the interest to work from a fairness perspective should be more studied.

Studies should develop performance measures that reflect the social approach, especially the social value-creation measures and the social impact, and all intangible results that involve those organizations.

Although legal characteristics differentiate NPOs from PAs, both types of organization present similar features and can be evaluated considering their primary approach, i.e., the social mission. All design factors are related to both organization types, and a study covering them is not well advanced yet.

Finally, the factors can be applied in a survey with NPOs to evaluate their applicability and discuss how distinct they are from the private sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.M., E.P.L. and F.D.; methodology, L.F.M., E.P.L., F.D., S.E.G.d.C., R.D. and R.A.K.; validation, L.F.M., E.P.L., F.D. and E.V.A.; formal analysis, L.F.M., F.D., S.E.G.d.C., R.D. and R.A.K.; investigation, L.F.M., S.E.G.d.C., R.D. and R.A.K.; resources, L.F.M., E.P.L., F.D. and E.V.A.; data curation, L.F.M., E.P.L. and F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.M. and F.D.; writing—review and editing, L.F.M., E.P.L. and F.D.; supervision, E.P.L. and E.V.A.; project administration, L.F.M., E.P.L., E.V.A. and S.E.G.d.C.; funding acquisition, E.P.L., E.V.A. and S.E.G.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to thank CNPq (National Council of Technological and Scientific Development) for supporting the research project through grant 307871/2012-6 and CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) for the scholarship through grant 88887.094594/2015-00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Case Study Questionnaire.

Table A1.

Case Study Questionnaire.

| Group | Factor | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Social approach | How are the social value and impact evaluated? Are the community interests analysed and transformed into performance indicators? How? How do you assess if the mission is being accomplished? |

| Stakeholders | Accountability | Are the data on performance measurement communicated externally? How? Is the information generated in the system/spreadsheets used for accountability to stakeholders? How? |

| Legitimacy | Does the data generated and reported through the system contribute to the organization’s legitimacy? Does the use of the system have this purpose? | |

| Volunteering | Is there access/metric/evaluation developed for volunteers? Which are they? | |

| Involvement and influence of stakeholders | How can the PM be influenced by the difference of interests and metrics for different stakeholders? Has the system any adaptation in its design to meet some stakeholder requirements? | |

| Management | Financial sustainability | Does the PMS manage the different sources of income? |

| Short and long-term planning | How does the system consider goals and outcomes for the short and long term? Was there any system/spreadsheets/procedures adaptation to meet a short or long-term request by a stakeholder? | |

| Fairness | Does the organization meet some inter-local equity requirements? If yes, how is this procedure? | |

| Efficiency and effectiveness | How is efficiency measured? Are the criteria to measure results well-established in the PMS? How do you evaluate effectiveness? Does PM consider intangible results? If yes, how? How to indicate a positive result, although the financial impact does not show it? What are the difficulties in measuring performance and working with these data? Does the PMS allow for monitoring and generating performance reports? | |

| Strategic management control | Is the PMS available for use at all levels of the organization? Is the system developed to support learning and continuous improvement in the organization? |

References

- Amado, Carla Alexandra da Encarnação Fili, and Sérgio Pereira dos Santos. 2009. Challenges for performance assessment and improvement in primary health care: The case of the Portuguese health centres. Health Policy 91: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonymous. 2020. Research from Brazil provides framework to design performance measurement systems (PMS) in non-profit and public administration organizations. Human Resource Management International Digest 28: 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, Marika, Giovanni Azzone, and Irene Bengo. 2015. Performance Measurement for Social Enterprises. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-Profit Organizations 26: 649–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, Malin, and Fergus Lyon. 2014. Social Impact Measurement and Non-profit Organisations: Compliance, Resistance, and Promotion. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations 25: 869–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabonienė, Ingrida, and Giedrė Večerskienė. 2015. The Aspects of Performance Measurement in Public Sector Organization. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 213: 314–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, Mark, Thomas Y. Choi, and Mei Li. 2011. Qualitative case studies in operations management: Trends, research outcomes, and future research implications. Journal of Operations Management 29: 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, Margo. 2014. Productivity in Public and Non-Profit Organizations, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bititci, Umit S. 2015. Managing Business Performance: The Science and the Art. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bracci, Enrico, Laura Maran, and Robert Inglis. 2017. Examining the process of performance measurement system design and implementation in two Italian public service organizations. Financial Accountability & Management in Governments, Public Services and Charities 33: 406–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cestari, José Marcelo Almeida Prado, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Eileen Morton Van Aken, Fernanda Treinta, and Louisi Francis Moura. 2018. A case study extension methodology for performance measurement diagnosis in non-profit organizations. International Journal of Production Economics 203: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestari, Jose Marcelo Almeida Prado, Fernanda Tavares Treinta, Louisi Francis Moura, Juliano Munik, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Sergio E. Gouvea da Costa, Eileen M. Van Aken, Luciana Rosa Leite, and Rafael Duarte. 2021. The characteristics of non-profit performance measurement systems. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2021: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Cheryl, and Linda Brennan. 2012. Entrepreneurship with social value: A conceptual model for performance measurement. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 18: 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan, Ram A., and Toni A. Cascio. 1998. Performance and Commitment: Issues in management of volunteers in human service organizations. Journal of Social Service Research 24: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaty, Frank J. 2012. Performance management challenges in hybrid NPO/public sector settings: An Irish case. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 61: 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Ciaran, and Martin Kelly. 2011. Understanding accountability in social enterprise organisations: A framework. Social Enterprise Journal 7: 224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, Lynne, and Pinar Guven Uslu. 2012. UK health sector performance management: Conflict, crisis and unintended consequences. Accounting Forum 36: 231–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, Carolyn, and Rowena Sinclair. 2013. Measuring performance in the third sector. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 10: 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Crucke, Saskia, and Adelien Decramer. 2016. The Development of a Measurement Instrument for the Organizational Performance of Social Enterprises. Sustainability 8: 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daff, Lyn, and Lee D. Parker. 2021. A conceptual model of accountants’ communication inside not-for-profit organisations. The British Accounting Review 53: 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, Edson Pinheiro, Sergio E. Gouvea da Costa, Jannis Jan Angelis, and Juliano Munik. 2013. Performance measurement systems: A consensual analysis of their roles. International Journal of Production Economics 146: 524–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBusk, Gerald K., Robert M. Brown, and Larry N. Killough. 2003. Components and relative weights in utilization of dashboard measurement systems like the Balanced Scorecard. The British Accounting Review 35: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobmeyer, Thomas W., Barry Woodward, and Lucille Olson. 2002. Factors Supporting the Development and Utilization of an Outcome-Based Performance Measurement System in a Chemical Health Case Management Program. Administration in Social Work 26: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Zuluaga, Lola C., and Ulrike Schneider. 2008. Market Orientation and Organizational Performance in the Non-profit Context: Exploring Both Concepts and the Relationship between Them. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 19: 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ebinger, Falk, Stephan Grohs, and Renate Reiter. 2011. The Performance of Decentralisation Strategies Compared: An Assessment of Decentralisation Strategies and their Impact on Local Government Performance in Germany, France and England. Local Government Studies 37: 535–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ebrahim, Alnoor, and V. Kasturi Rangan. 2014. What Impact? A framework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. California Management Review 56: 118–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, Teresa, António Samagaio, and Ricardo Rodrigues. 2021. Adoption of management control systems and performance in public sector organizations. Journal of Business Research 124: 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoroudis, Evangelos, Eva Orfanoudaki, and Constantin Zopounidis. 2012. Strategic performance measurement in a healthcare organisation: A multiple criteria approach based on balanced scorecard. Omega 40: 104–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Elisa, and Vicky Lambert. 2018. Negotiating for survival: Balancing mission and money. The British Accounting Review 50: 185–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Zahirul. 2014. 20 years of studies on the balanced scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research. The British Accounting Review 46: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, Noel, and Danielle McConville. 2018. Trust and accountability in UK charities: Exploring the virtuous circle. The British Accounting Review 50: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, Noorein S., Robert S. Kaplan, Mary Lou Helfrich Jones, and Rita Menitoff. 2000. The balanced scorecard: A strategic management system for multi-sector collaboration and strategy implementation. Quality Management in Health Care 8: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevanesan, Thivya, Jiju Antony, Bryan Rodgers, and Anupama Prashar. 2021. Applications of continuous improvement methodologies in the voluntary sector: A systematic literature review. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 32: 431–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Sheri Chaney. 2014. Impact and Excellence: Data-Driven Strategies for Aligning Mission, Culture and Performance in Non-Profit and Government Organizations. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, Dinar. 2019. Mind the gap: Investigating the role of collective action in the evolution of Indian medical device regulation. Technology in Society 59: 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S. 2001. Strategic Performance Measurement and Management in Non-profit Organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 11: 353–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 1992. The balanced scorecard—Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 83: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 1996. Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System. Harvard Business Review 1996: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Karwan, Kirk R., and Robert E. Markland. 2006. Integrating service design principles and information technology to improve delivery and productivity in public sector operations: The case of the South Carolina DMV. Journal of Operations Management 24: 347–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Eric. 2010. Innovation processes in social enterprises: An IC perspective. Journal of Intellectual Capital 11: 158–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Shashank, Rakesh D. Raut, Maciel M. Queiroz, and Balkrishna E. Narkhede. 2021. Mapping the barriers of AI implementations in the public distribution system: The Indian experience. Technology in Society 67: 101737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chongmyoung, and Branda Nowell. 2015. A Framework for Assessing the Performance of Nonprofit Organizations. American Journal of Evaluation 36: 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leotta, Antonio, and Daniela Ruggerii. 2017. Performance measurement system innovations in hospitals as translation processes. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 30: 955–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liguori, Mariannunziata, and Ileana Steccolini. 2018. The power of language in legitimating public-sector reforms: When politicians “talk” accounting. The British Accounting Review 50: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Florentine, Christian Schober, Ruth Simsa, and Reinhard Millner. 2015. SROI as a Method for Evaluation Research: Understanding Merits and Limitations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-Profit Organizations 26: 1805–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, Laura, Enrico Bracci, and Robert Inglis. 2018. Performance management systems’ stability: Unfolding the human factor—A case from the Italian public sector. The British Accounting Review 50: 324–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, Sara Giovanna, Lino Cinquini, and Daniela Pianezzi. 2019. New Public Management between reality and illusion: Analysing the validity of performance-based budgeting. The British Accounting Review 53: 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, Jessica, Mark Shoesmith, and Richard Allen. 2010. Embedding outcomes recording in Barnardo’s performance management approach. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 59: 586–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, Sonia, and Smriti Verma. 2015. An assessment approach for enhancing the organizational performance of social enterprises in India. Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 7: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Kenneth A., and Wim A. Van der Stede. 2007. Management Control Systems: Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Incentives. New York: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Micheli, Pietro, and Mike Kennerley. 2005. Performance measurement frameworks in public and non-profit sectors. Production Planning & Control 16: 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mouchamps, Hugues. 2014. Weighing elephants with kitchen scales: The relevance of traditional performance measurement tools for social enterprises. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 63: 727–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, Louisi Francis, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Sergio Eduardo Gouvea da Costa, Fernando Deschamps, and Eileen Van Aken. 2016. Identifying the Factors that Influence the Design of Performance Measurement Systems in Not-for-Profit Organizations. Paper presented at American Society for Engineering Management 2016 International Annual Conference, Indianapolis, IN, USA, October 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, Louisi Francis, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Eileen Van Aken, Sergio E. Gouvea da Costa, Fernanda Tavares Treinta, and José Marcelo Almeida Prado Cestari. 2019. Designing performance measurement systems in non-profit and public administration organizations. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 68: 1373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, Louisi Francis, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Eileen M. Van Aken, Sergio E. Gouvea Da Costa, Fernanda Tavares Treintaa, José Marcelo Almeida Prado Cestari, and Ronan Assumpção Silva. 2020. Factors for performance measurement systems design in non-profit organizations and public administration. Measuring Business Excellence 24: 377–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxham, Claire. 2009. Performance measurement: Examining the applicability of the existing body of knowledge to non-profit organisations. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 29: 740–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moxham, Claire. 2014. Understanding third sector performance measurement system design: A literature review. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 63: 704–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munik, Juliano, Louisi Francis Moura, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, and Sergio Eduardo Gouvea da Costa. 2016. Performance measurement systems in non-profit organization: A bibliometric analysis. Paper presented at American Society for Engineering Management 2016 International Annual Conference, Charlotte, NC, USA, October 26–29; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Munik, Juliano, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Sergio E. Gouvea Da Costa, Eileen M. Van Aken, José Marcelo Almeida Prado Cestari, Louisi Francis Moura, and Fernanda Treinta. 2021. Performance measurement systems in non-profit organizations: An authorship-based literature review. Measuring Business Excellence 25: 245–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navimipour, Nima Jafari, Farnaz Sharifi Milani, and Mehdi Hossenzadeh. 2018. A model for examining the role of effective factors on the performance of organizations. Technology in Society 55: 166–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, Andy, Chris Adams, and Paul Crowe. 2001. The performance prism in practice. Measuring Business Excellence 5: 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Linh, Betina Szkudlarek, and Richard G. Seymour. 2015. Social impact measurement in social enterprises: An interdependence perspective. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 32: 224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordin, Nazrul Hazizi, Siti Nurah Haron, and Salina Kassim. 2017. Developing a comprehensive performance measurement system for waqf institutions. International Journal of Social Economics 44: 921–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcott, Deryl, and Tuivaiti Ma’amora Taulapapa. 2012. Using the balanced scorecard to manage performance in public sector organizations: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Public Sector Management 25: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, Maria Grazia, and Giuseppe Paolo Ferulano. 2016. Intellectual capital and performance measurement in healthcare organizations: An integrated new model. Journal of Intellectual Capital 17: 320–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, Mark. G. 1998. Creating High-Performance Government Organizations. Edited by Mark G. Popovich. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Raus, Marta, Jianwei Liu, and Alexander Kipp. 2010. Evaluating IT innovations in a business-to-government context: A framework and its applications. Government Information Quarterly 27: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, Nigusse W. 2017. Balanced scorecard in higher education institutions: Congruence and roles to quality assurance practices. Quality Assurance in Education 25: 489–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Robert, and Raisa Deber. 2016. The performance measurement -management divide in public health. Health Policy 120: 273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, Mark C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar]

- Sinuany-Stern, Zilla, and H. David Sherman. 2014. Operations research in the public sector and non-profit organizations. Annals of Operations Research 221: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysa, Ishani Buddika, Nihal Palitha Jayamaha, and Nigel Peter Grigg. 2018. Developing a strategic performance scoring system for healthcare non-profit organisations. Benchmarking: An International Journal 25: 3654–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Margaret, and Andrew Taylor. 2014. Performance measurement in the Third Sector: The development of a stakeholder-focussed research agenda. Production Planning & Control 25: 1370–85. [Google Scholar]

- Treinta, Fernanda T., Louisi F. Moura, Jose M. Almeida Prado Cestari, Edson Pinheiro de Lima, Fernando Deschamps, Sergio Eduardo Gouvea da Costa, Eileen M. Van Aken, Juliano Munik, and Luciana R. Leite. 2020. Design and implementation factors for performance measurement in non-profit organizations: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, Vladislav. 2011. The Meaning of Nonprofit Organization: Insights from Classical Institutionalism. Journal of Economic Issues XLV: 901–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wellens, Lore, and Marc Jegers. 2014. Effective governance in non-profit organizations: A literature based multiple stakeholder approach. European Management Journal 32: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Cherrie, and Deryl Northcott. 2018. Unveiling the role of identity accountability in shaping charity outcome measurement practices. The British Accounting Review 50: 214–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).