Abstract

The public policies implemented in order to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the community have created issues both in the internal and the external environments of the Greek rural healthcare enterprises. This study aimed to investigate the full extent of the issues (internal and external) caused by the public policies. Regarding the external factors, we examined the state, the local authorities, the financial institutions, the social stakeholders and the citizens. Regarding the internal factors, we focused on turnover, liquidity, working conditions, internal changes related to patient care and the implementation of protective measures. A qualitative research was conducted among twelve rural healthcare business owners in the form of semi-structured interviews. The research was conducted in the fall of 2020 during the second phase of COVID-19. The research showed that these enterprises were severely impacted by the government’s public policies. Local authorities were not involved due to lack of competence. The business owners were unwilling to support their enterprises via bank lending. During the first phase of COVID-19, citizens postponed nonessential medical examinations, causing a reduction in these enterprises’ turnover. As a result, in the following periods, these enterprises faced liquidity problems. However, they developed social objectives and implemented protective measures for their employees and patients. The present study contributes to the mapping of the factors affecting the internal and external environments of rural healthcare enterprises along with the public policies developed in times of prolonged crisis. These kinds of data are crucial to the business world and government officials voting on social policies. One cannot rule out the possibility of a new financial or health crisis; the findings of this study can prove to be a useful tool in the process of decision making.

1. Introduction

Public policies developed to contain the spread of COVID-19 disturbed the social and financial life of citizens and imposed changes on their living conditions and purchase habits (Thomas and Chackole 2021; Nicola et al. 2020). At the same time, the public policies to contain COVID-19 created problems both in the internal and the external environment of enterprises in rural areas (Apostolopoulos et al. 2021a; Liguori and Pittz 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic proved that economy and health are two strongly interlinked aspects of social life (Tandon et al. 2020). Many countries, especially the most financially vulnerable, have experienced shortages in health commodities during the pandemic, such as facemasks, ventilators and other essential products (Kaye et al. 2020; Williams 2020). Even the vaccine production generated further inequalities among the countries as well as among the citizens (Clouston et al. 2021; Cheong et al. 2020). On the other hand, enterprises and society are interlinked (Sheth 2020). The failure of enterprises to operate normally has impacted the social cohesion and the global economy (Donthu and Gustafsson 2020; Lucaci and Nastase 2020). Among the gravest issues rural healthcare enterprises faced were insecurity, difficulty obtaining supplies and funding, reduced turnover and thwarting of investment plans (Apostolopoulos et al. 2021a; Williams et al. 2021).

The pandemic of COVID-19 found the Greek healthcare system already weak and deteriorating due to major cutbacks in funding as a result of the 2009 financial crisis and the country’s long-term reliance on the support and supervision mechanisms (Siettos et al. 2021; Giannopoulou and Tsobanoglou 2020). Hospitals located away from major urban centers, community health centers and rural GP clinics usually addressing the needs of the rural population had been deteriorating due to the 2009 financial crisis, dealing with staff shortages, collapsing infrastructure and outdated medical equipment (Economou et al. 2017; Mitropoulos et al. 2016). Therefore, the rural population lacked access to reliable public health services (Vardiampasis et al. 2014) and had to turn to private clinics which are more popular among the citizens (Tountas et al. 2011).

Despite the problems afflicting the Greek healthcare system, the country took immediate action against the spread of COVID-19, which resulted in the first wave of the pandemic being adequately handled, earning Greece international praise (Siettos et al. 2021; Kousi et al. 2021; Gountas et al. 2020). In the following months, the easing of restrictions and the opening of the catering sector was decided, as well as the opening of tourism under certain conditions. In the fall of 2020, Greece was confronted with the second wave of the pandemic and the country’s delayed response endangered the stability of the healthcare system (Farsalinos et al. 2021; Apostolopoulos et al. 2021b). The involvement of private enterprises in dealing with COVID-19 patients was low and restricted to major urban centers. In February 2021 Greece was confronted with a third wave of the pandemic, which was much more severe than the previous ones, and the public health institutions were unable to face this challenge on their own. The government had to requisition medical staff from the private sector and commandeer private health facilities. In March 2021, the private health sector provided to the public hundreds of Intensive Care Units in order to support the National Healthcare System.

The present primary research seeks to investigate the impact of the public policies designed to deal with COVID-19 on healthcare enterprises located in rural areas of Greece by examining their internal and external environment. It also seeks to detect the opinions of healthcare business owners on the impact of these policies on their enterprises. The examination of the sustainability of healthcare enterprises in a time of crisis, their adaptability to public policies and their resilience are issues which are addressed in this research and the results will be a useful tool for dealing with similar situations. It is a fact that the health crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the socioeconomic environment of enterprises as well as the daily lives of the citizens. Moreover, Greece which in the financial crisis of 2009 did not make it as far as recovering from the shock and was forced to enter into support mechanisms (Vasilopoulou et al. 2014; Pappas 2014), tackled the COVID-19 pandemic effectively through the pursued public policies. (Bamias et al. 2020; Moris and Schizas 2020). This research examines whether health firms showed adaptability and resilience to the crisis and, if so, what contributed to it. The outcome of the research will be a useful tool in decision-making centers in future crises.

2. Literature Review

Following the implementation of restrictive measures, many private and public healthcare units embarked on new treatment methods using digital techniques (Dantas et al. 2020; Pinto and de Carvalho 2020; Pelicioni and Lord 2020). These techniques were applied in several conditions whenever possible in order to overcome the obstacles created by the lockdown (Ozturk et al. 2021; Dantas et al. 2020). In Germany, there has been an extensive use of telehealth during COVID-19 and a study conducted by Peine et al. (2020) showed that private clinics were more adaptable in using telehealth while their employees faced fewer technical issues compared to University Hospitals. A research by Sethi et al. (2020) conducted in private and public healthcare facilities showed that during COVID-19, healthcare professionals working in these facilities were being subjected to an unmanageable workload, which was detrimental to their mental, physical and social well-being. According to a study by Lystad et al. (2020) on the impact of COVID-19 on manual therapy, service in private healthcare facilities found a large-scale impact to an unknown extent. Even the rural healthcare enterprises themselves were confronted with challenges such as reduced turnover and liquidity problems (Apostolopoulos et al. 2021a). What makes this research so important is that it found that rural healthcare enterprises adjusted quickly to the new circumstances and were able to display resilience. In many poor countries, private clinics were closed down due to shortages in protective equipment, problems in transportation and provider unavailability (Cousins 2020; Nouhjah and Jahanfar 2020; Bhattacharya et al. 2020). In many countries, there have been cases of canceling scheduled examinations in public healthcare facilities, such as surgical procedures. In these cases, the patients were referred to private clinics where the hospitalization costs could be covered by the National Healthcare System (Pang et al. 2020). Some countries like Switzerland established a public–private cooperation program, so that patients who tested negative for COVID-19 could be directly referred to various private clinics for treatment and hospitalization (Molliqaj and Schaller 2020). The same happened in many other European countries. In Italy, a country with a considerably high rate of COVID-19 mortality, the private healthcare sector provided thousands of beds to support the collapsing public healthcare system (Di Lorenzo and Di Trolio 2020). Many governments adopted systems of private–public cooperation in their healthcare sector in order to mitigate the pressure put on them by COVID-19 on public healthcare facilities. Baxter and Casady (2020) believe this experience will lead to the future adoption by many governments of similar cooperation systems, even though this is by no means a panacea for all the shortages and problems of the healthcare sector. The private healthcare sector also supported the vaccination program in many cases (Petersen et al. 2021). The research conducted by Apostolopoulos et al. (2021b) on healthcare entrepreneurship in small cities during COVID-19 concluded that healthcare enterprises faced challenges caused by the restrictive public policies to contain COVID-19. These challenges were identified in raw materials supply, reduced turnover and liquidity as well as in changes made to the way they provided their services to patients. A study by Govindan et al. (2020) also detected problems in the supply chain of healthcare institutions. Another study, by Williams (2020), also concluded in the existence of a liquidity crisis in such enterprises. The findings of Nimako et al. (2020) showed that an assessment of private healthcare institutions during COVID-19 is necessary in order to develop the private sector’s ability to handle emergencies.

3. Methodology

In order to detect the views of healthcare entrepreneurs on business issues as far as the impact of public policies to address the COVID-19 pandemic, we chose the phenomenological approach. It is a recognized approach of exploratory experiences of both the entrepreneurship issues and the healthcare issues (Pringle et al. 2011). It is widely used to explore experiences in research in health, healthcare and issues concerning healthcare professionals (Norlyk and Harder 2010; Thomas and Pollio 2002; Whiting 2001). Moreover, it is used in entrepreneurship issues, since it approaches better the entrepreneurial environment that shapes opportunities and challenges (Al-Dajani et al. 2019; Cope 2005). The paradigm of interpretivism covers the present study as well, since this seeks to reflect the experiences and the views of the entrepreneurs on the internal and external environment of their healthcare enterprises (Van der Walt 2020; Levi-Sanchez and Toupin 2014). Based on the interpretative perceptual outline, we also developed the framework of our research questions. The paradigm of interpretivism is a paradigm of qualitative nature and needs qualitative research methods with interviews and discussions with the research participants (Levi-Sanchez and Toupin 2014; Williams and Morrow 2009). The selection of the interpretative outline that means in-depth understanding and interpretation of personal perceptions, beliefs and experiences of the healthcare entrepreneurs on entrepreneurship issues led us to the selection of the qualitative research. The qualitative research aims at the development of the understanding of the meaning and the experience of people (Fossey et al. 2002), something that we seek. It is considered appropriate in entrepreneurship issues, because it approaches and understands the unique, volatile and natural characteristics (Van Burg et al. 2020). The qualitative research is also applied in the field of healthcare enterprises and it is indeed considered as effective (Sharma et al. 2020; Matthews-Trigg et al. 2019; Dieckmann et al. 2012). For the creation of qualitative data, the in-depth individual interviews for data collection are considered one of the most effective methods (McCracken 1988). For the present qualitative study, we chose the semi-structured interview, since this is used very frequently in the entrepreneurship issues with validity and reliability (Creswell and Poth 2016; Qu and Dumay 2011). Semi-structured interviews are considered appropriate when the researcher wishes to collect qualitative open data and when he aims to explore thoughts, feelings, beliefs and views of the participants (DeJonckheere and Vaughn 2019).

To select the way of sampling, we chose the convenience sampling since this is often widely used in the examination of entrepreneurial phenomena and issues of primary healthcare (Kathiravan et al. 2019; Moser and Korstjens 2018; Given 2008). We proceeded on the basis of the literature mentioning that the size of the sample has to be small in order to keep the subjective and individual characteristics (Moser and Korstjens 2017; Polit and Beck 2017). We did not define a priori sample size since this contradicts the principle of saturation. The saturation is a necessary element in qualitative research and the sample size is determined by this factor (Fusch and Ness 2015). In the present study, the saturation took place at twelve interviews, while we needed to contact twenty entrepreneurs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected healthcare enterprises.

The enterprises we surveyed belong in the wider sector of healthcare and referred to the entire spectrum of sizes and legal forms. They provide healthcare services to the rural population of Greece. The sample consists of physiotherapy facilities, speech therapy facilities, laboratory testing services, dental and cardiological care facilities, polyclinics, psychiatric care, pharmacies and rehabilitation centers. They are located in the administrative regions of Peloponnese, Western Greece, Epirus, Attica, Thessaly, Central Greece and Western Macedonia.

Our research was conducted in the fall of 2020, when Greece faced the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our semi-structured interviews were carried out with the owners of the selected healthcare enterprises, each lasting forty minutes on average. The restrictive measures imposed at the time through the public policies aimed at containing the spread of COVID-19 in our community led us to use the internet and phone to conduct the interviews. The use of the internet and phone in collecting data is, according to the literature, equally reliable as interviews carried out in person (McIntosh and Morse 2015; Deakin and Wakefield 2014). Our semi-structured interviews were carried out in Greek.

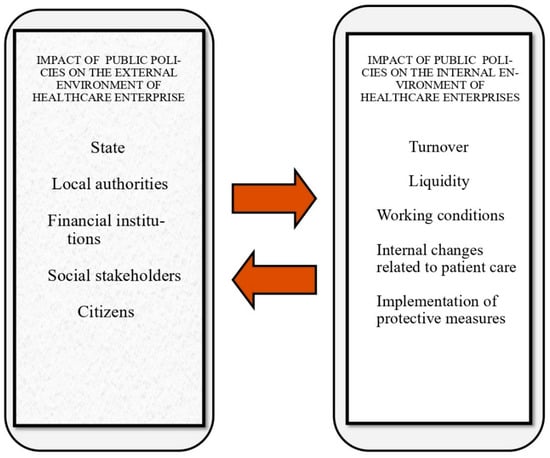

The research team focused on two directions in order to reveal all the aspects of the impact of public policies on healthcare enterprises (Figure 1). On the one hand, we focused on the impact of these policies on the external environment of the healthcare enterprises. Among the factors examined were the state, the local administration, the financial institutions, the social stakeholders and the citizens. On the other hand, we focused on the impact of these policies on the internal environment of the healthcare enterprises, examining factors such as the impact on turnover, liquidity, working conditions, protective measures, and patient care.

Figure 1.

Impacts on the internal and external environment of health businesses by COVID-19 public restraint policies.

4. Data Analysis

Given that one of the most important factors in qualitative research is systematic, thorough and controlled process of analysis (Thorne 1997), we took into account Morse’s analysis process (1994). The coding of themes through our discussions with the business owners highlighted the issues occurring both in the internal and the external environment of healthcare enterprises due to the public policies developed to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in community (Table 2). The business owners’ experiences were analyzed and classified according to theme and in emerging sub-themes (Apostolopoulos et al. 2019). Using the inductive method, the interviews were examined individually and cross-verification was conducted in relation to the two themes (Yin 1994). The emerging themes occurred following the inductive method as well in relation to the research questions set (Gioia et al. 2013), adjusted to issues related to COVID-19 pandemic crisis and the interaction of several factors in rural healthcare providers.

Table 2.

Emerging themes.

We followed the international practice of using the same language both in the data analysis and the semi-structured interviews in order to avoid misinterpretations and ensure that the analysis is precise and reliable (Maneesriwongul and Dixon 2004; Temple and Young 2004). Only the references used in the article were translated into English (Van Nes et al. 2010).

5. Findings

The findings were structured into two thematic categories. The first regarded the impact of public policies to contain the spread of COVID-19 on the external environment of healthcare enterprises in rural areas of Greece. The second regarded the impact of public policies to contain the spread of COVID-19 on the internal environment of healthcare enterprises in rural areas of Greece. The results of the semi-structures interviews on those issues are presented below, along with representative answers from the respondents on each issue analyzed.

- Impact of public policies to contain the spread of COVID-19 on the external environment of healthcare enterprises in rural areas

Firstly, we examined the factor of state support provided to these enterprises. All of the enterprises participating in our research stated that the government policies enforced had an impact on their operation. On the part of the state, there have been policies including financial support, albeit unable to compensate for the losses.

“The protective measures taken by the government in view of the pandemic created several problems for our healthcare facility. The costs increased and it is impossible to cover our losses with the financial support provided by the state to enterprises”.(R10)

The local administration’s involvement was limited, since the policies enforced were centrally planned and the measures taken in individual rural regions were centrally determined upon the recommendations given by the board of infectious disease specialists. All the enterprises examined stated that the cooperation with the local administration was excellent; however, the latter lacked the competence to address the issue of COVID-19. The public policies pursued by the government did not create a framework to support these enterprises through the local authorities and did not operate in a decentralized manner. This was something that was pointed out by the health entrepreneurs.

“Our cooperation with the local administration is ongoing on many issues, however regarding COVID-19 the local administration had limited power and small to minimal involvement with the private healthcare sector”.(R9)

Many public business support policies passed through financial institutions. They contained at the core bank loans and other facilities. The rural healthcare enterprises’ relations with financial institutions, especially the banks, were reluctant or even negative, and the business owners in the healthcare sector mentioned that this was the result of their experiences during the financial crisis of 2009. They were also skeptical when it came to financial support measures including bank lending.

“Right now a large amount of funding is provided in order to give the market a boost. What we don’t want is to be urged toward bank lending again, which is what happened during the financial crisis of 2009. Our experience with the banking system has been negative. The measures taken to support the enterprises must not include bank lending”.(R4)

The healthcare enterprises’ relations with social stakeholders were ongoing, especially with those representing vulnerable social groups.

“Our healthcare facility always had social objectives as well. We are in an ongoing cooperation with many social stakeholders. During COVID-19 we had several cases of individuals from vulnerable social groups sent to us for medical tests and treatment, and we were more than happy to deliver with no remuneration”.(R5)

Due to several issues afflicting public healthcare facilities where COVID-19 patients were hospitalized, the citizens were seeking the services of the private sector. Implemented public policies have also strengthened the private health sector to be accessible to citizens in order to decongest public structures.

“At first, before the enforcement of lockdown, business was becoming slow. People were reluctant to come to us for medical tests. But lately, that has changed. People started relaxing and they preferred the private sector as they considered it to be safer”(R3)

- Impact of public policies to contain the spread of COVID-19 on the internal environment of healthcare enterprises in rural areas

During the first phase of the spread of COVID-19, the turnover of these enterprises was reduced significantly. However, during the second phase, due to overload in hospitals, the citizens sought the services of the private healthcare sector. The public policies pursued in the first phase of the pandemic changed the daily lives of citizens and created fears and insecurities. Any disease that did not need immediate treatment was postponed. This situation quickly changed.

“The combination of services provided has changed. There has been a negative change in turnover during the first phase of the pandemic. Now the situation is constantly improving and our turnover is growing”(R8)

All the enterprises examined stated that they faced severe liquidity problems due to the public policies implemented to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic our expenses increased in many areas. All the measures imposed had a financial cost which we carried entirely on our shoulders. In order to maintain our good reputation and the quality of our services, we had to accumulate financial losses. The liquidity problem has aggravated”(R12)

There have been great changes in working conditions, since everything was adapted to health protocols proposed by the board of infectious disease specialists and Ministries of Health. The public policies carried out also contained ongoing checks on their faithful implementation.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the working conditions. Our main concern is to prevent the spread of the virus, because there are so many people here. We took strict precautionary measures and our staff is now working in unfavorable conditions. The spread of the virus in our facility would be a disaster first and foremost because we will have human losses, but the investment will also collapse”(R7)

The patient care changed due to protective measures. The public policies pursued to address the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic provided for strict protection measures, such as masks, thermometers, distances, doctor’s appointments and many other measures.

“Everything changed in the way we provide our services to the patients. We acted in strict accordance with the provisions concerning the measures of protection. The appointment is booked via telephone, we perform temperature controls, we keep the necessary distances, the use of mask is required and we are ready to perform Rapid Test”(R5)

Protective measures have a double function. They refer to the medical, nursing and other staff of healthcare enterprises, but also to the patients who had to present themselves only after booking an appointment in the healthcare facilities following the protective measures.

“We follow reverently the measures aimed at protecting us from the pandemic and so far this has brought results, since we never had any confirmed COVID-19 case in the facility. The measures are followed both by our staff and out patients”(R9)

6. Discussion

Our research has shown that public policies against the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in our community have generated challenges in the operation of the healthcare enterprises in rural areas of Greece. It showed three dimensions: the specificity of health enterprises and the nature of the services offered; their resilience towards the socioeconomic environment shaped by the restrictions imposed; the adaptability they showed in order to continue to offer responsibly and consistently quality services while maintaining their good reputation in the competitive environment. The support measures taken and implemented in favor of the enterprises by the Greek government have alleviated some of the financial issues of the enterprises, yet they have not resolved the problem, as the losses are far greater than what the support measures can cover. These findings are consistent with the findings of other researches in Greece (Apostolopoulos et al. 2021a, 2021b). They are also consistent with the existing studies in other countries (Singh et al. 2021; Sharpe et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2020; Leite et al. 2020). Almost every country has taken measures to support enterprises, as was the case in Greece (Danielli et al. 2021; Brülhart et al. 2020). The present research has shown that due to lack of competence, the local administration in regions of Greece was not involved in the public policies impacting the healthcare enterprises in rural areas, since the public policies against the spread of COVID-19 were centrally imposed. This finding contradicts the findings of researches in other countries, where the local administrations had an active role in the policies against the spread of COVID-19 in the community as well as in the operation of the local enterprises as a whole. The involvement of local authorities in such issues is critical, in order to reduce the pressure that the urban public hospitals and healthcare units confront and will alleviate the consequences of the pandemic crisis. Wright (2020) showed that in many countries the local administration had an important role in local enterprises when it came to mitigating the effects of COVID-19 and planning their recovery in the post-COVID-19 era. The same conclusion occurred in the study of Ramírez de la Cruz et al. (2020). Other countries used systems of local management of the risks posed by COVID-19 (Coghlan et al. 2020). Our findings indicate a hysteresis in that field. Thus, Greek governments should enhance focused policies towards the decentralization of those issues and overall authorities relative to the management of the pandemic crisis from local administration. Another critical issue, as highlighted in international literature, is the liquidity shortage in private rural healthcare enterprises, which is more intense in Greece, on the aftermath of the extended period of economic crisis. As the present research finds, the owners of rural healthcare enterprises seem to be unwilling to support their enterprises through bank lending, invoking their negative experiences with bank lending during the 2009 financial crisis. They are unwilling to participate in state or EU programs including bank lending. Even though in Greece, as in other countries, support programs for enterprises through the financial institutions have been available (Anderson et al. 2021; Satiani et al. 2020; Bartik et al. 2020), according to the managers of rural healthcare providers, there is a lot more that should be done in order to bridge the gap between their enterprises and the financial institutions. The present research showed that rural healthcare enterprises developed social objectives during COVID-19 and cooperated with social stakeholders, especially those representing vulnerable social groups in need of medical care. Public policies imposed on healthcare enterprises did not affect social goals, but instead strengthened them. The relationship between these enterprises and the citizens has passed through many stages. At the beginning of the pandemic, citizens were hesitant and avoided non-emergency medical examinations. Later, a shift has been observed in their attitudes and they started turning to the services of the private healthcare sector as they considered it to be safer. These findings are consistent with many other studies conducted in other countries, which showed an increase in the number of patients in private healthcare facilities. Some studies have shown that in many countries, patients were moved from public to private healthcare facilities, in order to decongest the public healthcare units (Pang et al. 2020; Molliqaj and Schaller 2020). Overall, our findings made clear that the general government should enforce all the above mentioned policy measures in order to enhance the role of private healthcare providers, contributing thus, indirectly, to the improvement of public health providers too, decongesting central urban hospitals and encouraging people from rural areas to use local health providers instead of moving to urban areas.

The present research also concluded that there have been changes in the internal business environment caused by the public policies developed to control the spread of COVID-19 in the community. The turnover during the first phase of the pandemic was reduced and it only started increasing just before and during the second phase. Studies conducted in other countries show a similar turnover reduction during the first phase of the pandemic (Musumeci et al. 2021; Kruse and Jeurissen 2020). A shift became particularly apparent when public hospitals started turning large departments into COVID-19 treatment units and patients started being referred to the private healthcare sector (Pang et al. 2020). The owners of rural healthcare enterprises faced liquidity problems due to the public policies. These findings are consistent with those of other studies. A study by Williams (2020) concluded that healthcare enterprises faced liquidity problems. The same conclusion was drawn by the study of Apostolopoulos et al. (2021a). The findings of this research indicate that there is a lot that should be done by government, in order to provide short-term financial support for working capital, along with the on-time arrangements of the on-time compensation of private healthcare providers for their services to the citizens, through the social security program. Liquidity is one of the most crucial factors in all kinds of businesses, for their survival and growth, and one of the main causes of bankruptcy. Thus, some focused policy measures should be enacted for the financial support of those enterprises.

The present research showed that working conditions in healthcare enterprises have changed. The medical, nursing, and other staff have worked in extremely unfavorable conditions due to the protective measures imposed by the public policies. These findings are consistent with those of other studies. A study by Sethi et al. (2020) showed that the employees working in healthcare facilities during COVID-19 have faced an unmanageable workload that was detrimental to their health. The same conclusion was drawn by McFadden et al. (2021). Moreover, the present research showed that the healthcare enterprises adapted their services to the protective measures. These measures had a dual direction. They were addressed both to the healthcare employees and the patients. Studies in several countries have shown that protective measures were taken everywhere to protect the patients and the healthcare professionals, and wherever they were followed, the spread of COVID-19 was minimal in employees and patients (Liu et al. 2020; Kuwahara et al. 2020; Menéndez 2020; Cirrincione et al. 2020).

The detection of the opinions of health sector entrepreneurs carried out with this survey highlighted the anxiety, insecurity and uncertainty they faced from the impact of the constant restrictions, which were imposed by public policies. The entrepreneurs initially had a different perception of the intensity and duration of COVID-19. They were interested in holding their position and keeping their reputation in the market by continuing to apply their standards and quality services. The duration of the pandemic increased their operating costs. Nevertheless, their companies showed adaptability and resilience.

7. Conclusions

During the first two phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, the public policies against the spread of COVID-19 impacted the internal and external environment of rural healthcare enterprises in Greece. Despite their many problems, their owners would not support their enterprises using bank lending, invoking previous negative experiences. They did not cooperate with local administration on COVID-19 matters, as the local boards lacked the competence to address such issues. During the first phase of the pandemic, their turnover was reduced, since non-emergency medical examinations were postponed by the patients. This trend gradually changed; however, the liquidity problems persisted. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these enterprises developed social objectives and implemented protective measures against the spread of the virus in two directions. The first was toward the medical, nursing and other staff of the business and the second was toward the patients.

The present research showed that the public policies implemented by the Greek government to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic created obstacles for healthcare enterprises. However, these enterprises showed adaptability to the socioeconomic conditions which were formed by the policies pursued. They also showed resilience and overcame the problems that the new conditions created in their operation and in the services offered. The study also captured the anxiety of the business world to ensure the sustainability of their business by serving their patients regardless of the cost.

The present research is not without limitations. A crucial fact to take into account is that the study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic was resolved. It examines the situation as it was up to the second phase of the pandemic and it is possible that the factors examined will continue to change. It also focuses on the business owners in order to detect the factors impacting rural healthcare enterprises. A similar study could be conducted based on the healthcare professionals working in these enterprises. The findings of the present study determine the research agenda which will inform future research after the definitive handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and I.M.; methodology, S.S. and S.A.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.A.; resources, N.A. and S.S.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to protection of the interviewees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Dajani, Haya, Hammad Akbar, Sara Carter, and Eleonor Shaw. 2019. Defying contextual embeddedness: Evidence from displaced women entrepreneurs in Jordan. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 31: 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Julia, Francesco Papadia, and Nicolas Véron. 2021. COVID-19 Credit Support Programs in Europe’s Five Largest Economies. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper No. 21-6. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3826517 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Apostolopoulos, Nikolaos, Panagiotis Liargovas, Pantelis Sklias, and Sotiris Apostolopoulos. 2021a. Healthcare enterprises and public policies on COVID-19: Insights from the Greek rural areas. Strategic Change 30: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, Nikolaos, Panagiotis Liargovas, Pantelis Sklias, Ilias Makris, and Sotiris Apostolopoulos. 2021b. Private healthcare entrepreneurship in a free-access public health system: What was the impact of the COVID-19 public policies? Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy. (In press). [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulos, Nikolaos, Robert Newbery, and Menelaos Gkartzios. 2019. Social enterprise and community resilience: Examining a Greek response to turbulent times. Journal of Rural Studies 70: 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bamias, Giorgos, Styliani Lagou, Michalis Gizis, George Karampekos, Konstantinos G. Kyriakoulis, Christos Pontas, and Gerassimos J. Mantzaris. 2020. The greek response to COVID-19: A true success story from an IBD perspective. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 26: 1144–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartik, Alexander W., Marianne Bertrand, Zoe Cullen, Edward L. Glaeser, Michael Luca, and Christopher Stanton. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117: 17656–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, David, and Carter B. Casady. 2020. Proactive and strategic healthcare public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the coronavirus (COVID-19) epoch. Sustainability 12: 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Sudip, Md Mahbub Hossain, and Amarjeet Singh. 2020. Addressing the shortage of personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in India-A public health perspective. AIMS Public Health 7: 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brülhart, Marius, Lalive Rafael, Tobias Lehmann, and Michael Siegenthaler. 2020. COVID-19 financial support to small businesses in Switzerland: Evaluation and outlook. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 156: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Mark Wing Loong, Pascale Allotey, and Daniel D. Reidpath. 2020. Unequal Access to Vaccines Will Exacerbate Other Inequalities. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 32: 379–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirrincione, Luigi, Fulvio Plescia, Caterina Ledda, Venerando Rapisarda, Daniela Martorana, Raluca E. Moldovan, Kelly Theodoridou, and Emanuele Cannizzaro. 2020. COVID-19 pandemic: Prevention and protection measures to be adopted at the workplace. Sustainability 12: 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, Sean A. P., Ginny Natale, and Bruce G. Link. 2021. Socioeconomic inequalities in the spread of coronavirus-19 in the United States: A examination of the emergence of social inequalities. Social Science and Medicine 268: 113554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, Niall, David Archard, Pippa Sipanoun, Thomas Hayes, and Behrad Baharlo. 2020. COVID-19: Legal implications for critical care. Anaesthesia 75: 1517–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, Jason. 2005. Researching entrepreneurship through phenomenological inquiry: Philosophical and methodological issues. International Small Business Journal 23: 163–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, Sophie. 2020. COVID-19 has “devastating” effect on women and girls. The Lancet 396: 301–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Danielli, Shaun, Raman Patria, Patrice Donnelly, Hutan Ashrafian, and Ara Darzi. 2021. Economic interventions to ameliorate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy and health: An international comparison. Journal of Public Health 43: 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, Lucas Ogura, Rodrigo Py Gonçalves Barreto, and Cristine Homsi Jorge Ferreira. 2020. Digital physical therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 24: 381–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deakin, Hannah, and Kelly Wakefield. 2014. Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research 14: 603–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonckheere, Melissa, and Lisa M. Vaughn. 2019. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health 7: e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Lorenzo, Giuseppe, and Rossella Di Trolio. 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Italy: Analysis of risk factors and proposed remedial measures. Frontiers in Medicine 7: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dieckmann, Peter, Friis M. Susanne, Lippert Anne, and Doris Østergaard. 2012. Goals, success factors, and barriers for simulation-based learning: A qualitative interview study in health care. Simulation and Gaming 43: 627–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, Naveen, and Anders Gustafsson. 2020. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research 117: 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, Charalampos, Daphne Kaitelidou, Marina Karanikolos, and Anna Maresso. 2017. Greece: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition 19: 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Farsalinos, Konstantinos, Konstantinos Poulas, Dimitrios Kouretas, Apostolos Vantarakis, Michalis Leotsinidis, Dimitrios Kouvelas, Anca O. Docea, Ronald Kostoff, Grigorios T. Gerotziafas, Michael N. Antoniou, and et al. 2021. Improved strategies to counter the COVID-19 pandemic: Lockdowns vs. primary and community healthcare. Toxicology Reports 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossey, Ellie, Carol Harvey, Fiona McDermott, and Larry Davidson. 2002. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 36: 717–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20: 1408. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopoulou, Ioanna, and George O. Tsobanoglou. 2020. COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities for the Greek health care system. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 37: 226–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Dennis A., Kevin G. Corley, and Aimee L. Hamilton. 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods 16: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, Lisa M., ed. 2008. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, ISBN 978-1-4129-4163-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gountas, Ilias, Georgios Hillas, and Kyriakos Souliotis. 2020. Act early, save lives: Managing COVID-19 in Greece. Public Health 187: 136–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, Kannan, Hassan Mina, and Behrouz Alavi. 2020. A decision support system for demand management in healthcare supply chains considering the epidemic outbreaks: A case study of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 138: 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathiravan, C., Padmaja Bhagavatham, V. Palanisamy, and A. Rajasekar. 2019. Influence of entrepreneurial creativity on competitive adnvantage in automobile engineering and technologies industries. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 27: 166–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, Alan D., Chikezie N. Okeagu, Alex D. Pham, Rayce A. Silva, Joshua J. Hurley, Brett L. Arron, Noeen Sarfraz, Hong N. Lee, Ghali E. Ghali, Jack W. Gamble, and et al. 2020. Economic Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Facilities and Systems: International Perspectives. Best Practice and Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousi, Timokleia, Lefkothea-Christina Mitsi, and Jean Simos. 2021. The Early Stage of COVID-19 Outbreak in Greece: A Review of the National Response and the Socioeconomic Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, Florien Margareth, and Patrick P. T. Jeurissen. 2020. For-profit hospitals out of business? Financial sustainability during the COVID-19 epidemic emergency response. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 9: 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara, Keisuke, Ai Hori, Norio Ohmagari, and Tetsuya Mizoue. 2020. Early cases of COVID-19 in Tokyo and occupational health. Global Health and Medicine 2: 118–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, Higor, Claire Lindsay, and Maneesh Kumar. 2020. COVID-19 outbreak: Implications on healthcare operations. The TQM Journal 33: 247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Sanchez, Suzanne, and Sophie Toupin. 2014. New Social Media and Global Resistance. In Gender Matters in Global Politics: A Feminist Introduction to International Relations. London: Routledge, pp. 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Liguori, Eric W., and Thomas G. Pittz. 2020. Strategies for small business: Surviving and thriving in the era of COVID-19. Journal of the International Council for Small Business 2: 106–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Zheng, Yawei Zhang, Xishan Wang, Daming Zhang, Dechang Diao, K. Chandramohan, and Christopher M. Booth. 2020. Recommendations for surgery during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic. Indian Journal of Surgery 82: 124–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaci, Ancuța, and Carmen Nastase. 2020. European Rural Businesses During The Covid-19 Pandemic: Designing Initiatives For Current And Future Development. LUMEN Proceedings 13: 419–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lystad, Reidar P., Benjamin T. Brown, Michael S. Swain, and Roger M. Engel. 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on manual therapy service utilization within the Australian private healthcare setting. Healthcare 8: 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneesriwongul, Wantana, and Jane K. Dixon. 2004. Instrument translation process: A method review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 48: 175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews-Trigg, Nathaniel, David Citrin, Scott Halliday, Bibhav Acharya, Sheela Maru, Stephen Bezruchka, and Duncan Maru. 2019. Understanding perceptions of global healthcare experiences on provider values and practices in the USA: A qualitative study among global health physicians and program directors. BMJ Open 9: e026020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCracken, Grant. 1988. The Long Interview. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, Paula, Jana Ross, John Moriarty, John Mallett, Heike Schroder, Jermaine Ravalier, Jill Manthorpe, Denise Currie, Jaclyn Harron, and Patricia Gillen. 2021. The role of coping in the wellbeing and work-related quality of life of UK health and social care workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, Michele J., and Janice M. Morse. 2015. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez, Uría. 2020. Spain’s response to Covid-19: Emergency measures; gradual relaxation. International Financial Law Review. Available online: https://www.iflr.com/article/b1lxmrrfr4gkfs/spains-response-to-covid19-emergency-measures-gradual-relaxation (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Mitropoulos, Panagiotis, Kostas Kounetas, and Ioannis Mitropoulos. 2016. Factors affecting primary health care centers’ economic and production efficiency. Annals of Operations Research 247: 807–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliqaj, Granit, and Karl Schaller. 2020. How neurosurgeons are coping with COVID-19 and how it impacts our neurosurgical practice: Report from Geneva University Medical Center. World Neurosurgery 139: 624–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moris, Dimitrios, and Dimitrios Schizas. 2020. Lockdown during COVID-19: The Greek success. In Vivo 34: 1695–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, Albine, and Irene Korstjens. 2017. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: Introduction. European Journal General Practice 23: 271–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moser, Albine, and Irene Korstjens. 2018. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice 24: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Musumeci, Maria Letizia, Maria Rita Nasca, and Giuseppe Micali. 2021. COVID-19: The Italian experience. Clinics in Dermatology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus and COVID-19 pandemic: A review. International Journal of Surgery 78: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimako, Belinda Afriyie, Frank Baiden, and John Koku Awoonor-Williams. 2020. Towards effective participation of the private health sector in Ghana’s COVID-19 response. The Pan African Medical Journal 35: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlyk, Annelise, and Ingegerd Harder. 2010. What makes a phenomenological study phenomenological? An analysis of peer-reviewed empirical nursing studies. Qualitative Health Research 20: 420–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouhjah, Sedigheh, and Shayesteh Jahanfar. 2020. Challenges of diabetes care management in developing countries with a high incidence of COVID-19: A brief report. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 14: 731–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Ayce B., Ayce Baççıoğlu, Ozge Soyer, Ersoy Civelek, Bulent E. Şekerel, and Sevim Bavbek. 2021. Change in allergy practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 182: 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Karl H., Diego M. Carrion, Juan G. Rivas, Guglielmo Mantica, Angelika Mattigk, Benjamin Pradere, Francesco Esperto, and European Society of Residents in Urology. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on European health care and urology trainees. European Urology 78: 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, Takis S. 2014. Populist democracies: Post-authoritarian Greece and post-communist Hungary. Government and Opposition 49: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peine, Arne, Pia Paffenholz, Lucas Martin, Sandra Dohmen, Gernot Marx, and Sven H. Loosen. 2020. Telemedicine in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: Multi-professional national survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e19745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicioni, Paulo H. S., and Stephen R. Lord. 2020. COVID-19 will severely impact older people’s lives, and in many more ways than you think! Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 24: 293–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Eskild, Daniel Lucey, Lucille Blumberg, Laura D. Kramer, Seif Al-Abri, Shui S. Lee, Tatiana C. A. Pinto, Christina W. Obiero, Alfonso J. Rodriguez-Morales, Richard Yapi, and et al. 2021. COVID-19 vaccines under the International Health Regulations–We must use the WHO International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 104: 175–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Fernandes T., and Celso R. F. de Carvalho. 2020. SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19): Lessons to be learned by Brazilian Physical Therapists. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 24: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, Denise F., and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2017. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, Jan, Charles Hendry, and Ella McLafferty. 2011. Phenomenological approaches: Challenges and choices. Nurse Researcher 18: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Sandy Q., and John Dumay. 2011. The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management 8: 238–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez de la Cruz, Edgar E., Eduardo J. Grin, Pablo Sanabria-Pulido, Daniel Cravacuore, and Arturo Orellana. 2020. The Transaction Costs of Government Responses to the COVID-19 Emergency in Latin America. Public Administration Review 80: 683–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satiani, Bhagwan, Todd A. Zigrang, and Jessica L. Bailey-Wheaton. 2020. COVID-19 financial resources for physicians. Journal of Vascular Surgery 72: 1161–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, Ahmed B., Ahsan Sethi, Sadaf Ali, and Hira S. Aamir. 2020. Impact of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 36: 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, Gagan D., Gaurav Talan, Mrinalini Srivastava, Anshita Yadav, and Ritika Chopra. 2020. A qualitative enquiry into strategic and operational responses to Covid-19 challenges in South Asia. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, Richard E., Jr., Brian S. Kuszyk, and Mahmud Mossa-Basha. 2021. Special report of the RSNA COVID-19 task force: The short-and long-term financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on private radiology practices. Radiology 298: 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, Jagdish. 2020. Business of business is more than business: Managing during the Covid crisis. Industrial Marketing Management 88: 261–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siettos, Constantinos, Cleo Anastassopoulou, Constantinos Tsiamis, Georgia Vrioni, and Athanasios Tsakris. 2021. A bulletin from Greece: A health system under the pressure of the second COVID-19 wave. Pathogens and Global Health 115: 133–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Devendra. R., Dev R. Sunuwar, Sunil K. Shah, Kshitij Karki, Lalita K. Sah, Bipin Adhikari, and Rajeeb K. Sah. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on health services utilization in Province-2 of Nepal: A qualitative study among community members and stakeholders. BMC Health Services Research 21: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, Ajay, Tomas Roubal, Lacklan McDonald, Peter Cowley, Toomas Palu, Valeria O. Cruz, Patrick Eozenou, Jewelwayne Cain, Hui S. Teo, Martin Schmidt, and et al. 2020. Economic Impact of COVID-19: Implications for Health Financing in Asia and Pacific. Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank. ©World Bank, Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34572 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Temple, Bogusia, and Alys Young. 2004. Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research 4: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Brian, and Swaroopa Chackole. 2021. Economic Impacts Of Covid 19. European Journal of Molecular and Clinical Medicine 7: 5812–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Sandra P., and Howard R. Pollio. 2002. Listening to Patients: A Phenomenological Approach to Nursing Research and Practice. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, Sally. 1997. The art (and science) of critiquing qualitative research. In Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue. Edited by J. M. Morse. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 117–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tountas, Yannis, Nikolaos Oikonomou, Georgia Pallikarona, Christine Dimitrakaki, Chara Tzavara, Kyriakos Souliotis, Anargiros Mariolis, Evelina Pappa, Nick Kontodimopoulos, and Dimitris Niakas. 2011. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic determinants of health services utilisation in Greece: The Hellas Health I study. Health Service Management Research 24: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Burg, Elco, Joep Cornelissen, Wouter Stam, and Sarah Jack. 2020. Advancing Qualitative Entrepreneurship Research: Leveraging Methodological Plurality for Achieving Scholarly Impact. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Walt, Johannes L. 2020. Interpretivism-Constructivism as a Research Method in the Humanities and Social Sciences–More to It Than Meets the Eye. International Journal 8: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, Fenna, Tineke Abma, Hans Jonsson, and Dorly Deeg. 2010. Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation? European Journal of Ageing 7: 313–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vardiampasis, Vasileios, Maria Tsironi, M. Athanasios Nikolentzo, Ioannis Moisoglou, Petros Galanis, Helen Stavropoulou, Georgia Athanasopoulou, and Panagiotis Prezerakos. 2014. Health services staffing with physicians in the remote areas: Recruitment and retention incentives. Archives of Hellenic Medicine/Arheia Ellenikes Iatrikes 31: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia, Daphne Halikiopoulou, and Theofanis Exadaktylos. 2014. Greece in Crisis: Austerity, Populism and the Politics of Blame. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52: 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, Lisa. 2001. Analysis of phenomenological data: Personal reflections on Giorgi’s method. Nurse Researcher (Through 2013) 9: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, David Owain, Ka Chun Yung, and Karen A. Grépin. 2021. The failure of private health services: COVID-19 induced crises in low-and middle-income country (LMIC) health systems. Global Public Health 16: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Elizabeth Nutt, and Susan L. Morrow. 2009. Achieving trustworthiness in qualitative research: A pan-paradigmatic perspective. Psychotherapy Research 19: 576–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Owain D. 2020. COVID-19 and Private Health: Market and Governance Failure. Development 63: 181–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, Carl. 2020. Local government fighting Covid-19. The Round Table 109: 338–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Kevin Y., David T. Wu, Thomas T. Nguyen, and Simon D. Tran. 2020. COVID-19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral Diseases 27: 684–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 1994. Discovering the future of the case study. Method in Evaluation Research. Evaluation Practice 15: 283–29. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).