Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Diversity in Organizations

2.1. Goals, Diversity, and Job Satisfaction

2.2. The Role of Diversity Management Policies

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection Instruments and Sample

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Model Controls

4. Analysis and Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Operational Definitions

- Considering everything how satisfied are you with your job?

- Considering everything how satisfied are you with your pay?

- Considering everything how satisfied are you with your organization?

- Managers communicate the goals and priorities of the organization.

- Managers review and evaluate the organization’s progress toward meeting its goals and objectives.

- I know how my work relates to the agency’s goals and priorities.

- Policies and programs promote diversity in the workplace (for example, recruiting minorities and women, training in awareness of diversity issues, mentoring).

- Prohibited Personnel Practices (for example, illegally discriminating for or against any employee/applicant, obstructing a person’s right to compete for employment, knowingly violating veterans’ preference requirements) are not tolerated.

- My supervisor/team leader is committed to a workforce representative of all segments of society.

References

- Blau, Peter M. 1977. Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Donn E. 1971. The Attraction of Paradigm. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Yoon Jik, and James L. Perry. 2012. Intrinsic motivation and employee attitudes: Role of managerial trustworthiness, goal directedness, and extrinsic reward expectancy. Review of Public Personnel Administration 32: 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Sungjoo. 2009. Diversity in the US federal government: Diversity management and employee turnover in federal agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 19: 603–30. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Sungjoo, and Hal G. Rainey. 2010. Managing diversity in U.S. federal agencies: Effects of diversity and diversity management on employee perceptions of organizational performance. Public Administration Review 70: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Young Han, and Hal G. Rainey. 2005a. Goal ambiguity in U.S. federal agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Young Han, and Hal G. Rainey. 2005b. Goal ambiguity and organizational performance in U.S. federal agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15: 529–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Taylor. 1993. Cultural Diversity in Organizations: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Taylor H., and Stacy Blake. 1991. Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. The Executive 5: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Taylor H., Sharon A. Lobel, and Poppy Lauretta McLeod. 1991. Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of Management Journal 34: 827–47. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Randall S., and Edmund C. Stazyk. 2015. Developing and testing a new goal taxonomy: Accounting for the complexity of ambiguity and political support. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25: 751–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Randall S., and Edmund C. Stazyk. 2016. Examining the links between senior managers’ engagement in networked environments and goal and role ambiguity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26: 433–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, Robin J. 2004. A field study of group diversity, participation in diversity education programs, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 755–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, Robin J., and David A. Thomas. 2001. Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly 46: 229–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldy, Erica Gabrielle. 2004. Learning from diversity: A theoretical exploration. Public Administration Review 64: 529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Fiona. 2020. Public Service and the Federal Government. Brookings. May 27. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/public-service-and-the-federal-government/ (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- House, Robert J., and John R. Rizzo. 1972. Toward the measurement of organizational practices: Scale development and validation. Journal of Applied Psychology 56: 388–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, Jeffrey M. 2008. The Multicultural Economy 2003: America’s Minority Buying Power. Washington, DC: The Hispanic Association on Corporate Responsibility. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancevich, John M., and Jacqueline A. Gilbert. 2000. Diversity management: Time for a new approach. Public Personnel Management 29: 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Susan E., Aparna Joshi, and Niclas L. Erhardt. 2003. Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management 29: 801–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, Jaehee. 2019. Racial diversity and task performance: The roles of formalization and goal setting in government organizations. Public Personnel Management 48: 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2005. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kochan, Thomas, Katerina Bezrukova, Robin Ely, Susan Jackson, Aparna Joshi, Karen Jehn, Jonathan Leonard, David Levine, and David Thomas. 2003. The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resource Management 42: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, Laura, and Edmund C. Stazyk. 2013. Vive la différence? The impact of diversity on the turnover intention of public employees and performance of public agencies. International Public Management Journal 16: 465–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, Gary P., and Edwin A. Locke. 2006. Enhancing the benefits and overcoming the pitfalls of goal setting. Organizational Dynamics 35: 332–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, Gary P., and Edwin A. Locke. 2007. New developments in and directions for goal setting. European Psychologist 12: 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, Tara. 2020. Women Are Now the Majority of the U.S. Workforce–But Working Women Still Face Serious Challenges. Time. January 16. Available online: https://time.com/5766787/women-workforce/ (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Llorens, Jared J., Jeffrey B. Wenger, and J. Edward Kellough. 2008. Choosing public sector employment: The impact of wages on the representation of women and minorities in state bureaucracies. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 18: 397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, Edwin A. 1976. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Marvin D. Dunnette. New York: Wiley, pp. 1297–350. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. 1990. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. 2002. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist 57: 705–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Locke, Edwin A., and Gary P. Latham. 2006. New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science 15: 265–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Karen, and Russell Spears. 1997. The self-esteem hypothesis revisited: Differentiation and the disaffected. In The Social Psychology of Stereotyping and Group Life. Edited by Russell Spears, Penelope J. Oakes, Naomi Ellemers and S. Alexander Haslam. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 296–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, Albert J., and Bernice E. Lott. 1961. Group cohesiveness, communication level, and conformity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 62: 408–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovich, George T., and Alexandra K. Wigdor. 1991. Pay for Performance: Evaluating Performance Appraisal and Merit Pay. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, William H., Stanley O. Horner, and Andrew T. Hollingsworth. 1978. An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 63: 408–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, William H., Rodger W. Griffeth, Herbert H. Hand, and Bruce M. Meglino. 1979. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin 86: 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Kuk-Kyoung, and Robert K. Christensen. 2020. Realizing the performance benefits of workforce diversity in the U.S. federal government: The moderating role of diversity climate. Public Personnel Management 49: 141–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naff, Katherine C., and J. Edward Kellough. 2003. Ensuring employment equity: Are federal diversity programs making a difference? International Journal of Public Administration 26: 1307–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Charles A., III, David F. Caldwell, and William P. Barnett. 1989. Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Administrative Science Quarterly 34: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Jesse E., and Luis L. Martins. 2012. Understanding organizational diversity management programs: A theoretical framework and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 33: 1168–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Sanghee, and Jiaqi Liang. 2020. Merit, diversity, and performance: Does diversity management moderate the effect of merit principles on governmental performance? Public Personnel Management 49: 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelled, Lisa Hope, Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, and Katherine R. Xin. 1999. Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey. 1983. Organizational demography. In Research in Organizational Behavior. Edited by Larry L. Cummings and Barry M. Staw. Greenwich: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, Anne Nederveen, Daan van Knippenberg, and Wendy P. van Ginkel. 2011. Diversity in goal orientation, team reflexivity, and team performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 114: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, David W. 2005. Diversity, representation, and performance: Evidence about race and ethnicity in public organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15: 615–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, David W. 2009. Diversity management, job satisfaction, and performance: Evidence from U.S. federal agencies. Public Administration Review 69: 328–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, David W., and Lois Recascino Wise. 2010. Workforce diversity in the new millennium: Prospects for research. Review of Public Personnel Administration 30: 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccucci, Norma M. 2002. Managing Diversity in Public Sector Workforces. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, John R., Robert J. House, and Sidney I. Lirtzman. 1970. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 15: 150–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Ellen V. 2009. The role of procedural justice in public personnel management: Empirical results from the Department of Defense. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19: 125–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selden, Sally Coleman, and Frank Selden. 2001. Rethinking diversity in public organizations for the 21st century: Moving toward a multicultural model. Administration & Society 33: 303–29. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Ken G., Ken A. Smith, Judy D. Olian, Henry P. Sims Jr., Douglas P. O’Bannon, and Judith A. Scully. 1994. Top management team demography and process: The role of social integration and communication. Administrative Science Quarterly 39: 412–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, Tom A. B., and Roel J. Bosker. 1999. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Stazyk, Edmund C. 2016. The prevalence of reinvention reforms in local governments and their relationship with organizational goal clarity and employee job satisfaction. Public Performance & Management Review 39: 701–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stazyk, Edmund C., and Randall S. Davis. 2015. Taking the ‘high road’: Does public service motivation alter ethical decision making processes? Public Administration 93: 627–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazyk, Edmund C., and Holly T. Goerdel. 2011. The benefits of bureaucracy: Public managers’ perceptions of political support, goal ambiguity, and organizational effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 645–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazyk, Edmund C., Randall S. Davis, and Shannon Portillo. 2017. More dissimilar than alike? Public values preferences across U.S. minority and white managers. Public Administration 95: 605–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Michael J., and Michael A. Campion. 1994. The knowledge, skill, and ability requirements for teamwork: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Management 20: 503–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1985. The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R. Roosevelt, Jr. 1990. From affirmative action to affirming diversity. Harvard Business Review 68: 107–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, David A., and Robin J. Ely. 1996. Making differences matter: A new paradigm for managing diversity. Harvard Business Review 74: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Toossi, Mitra. 2002. A Century of Change: The U.S. Labor Force, 1950–2050. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2002/05/art2full.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Toossi, Mitra. 2012a. Labor Force Projections to 2020: A More Slowly Growing Workforce. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2012/01/art3full.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Toossi, Mitra. 2012b. Labor Force Projections to 2020: A More Slowly Growing Workforce. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2012/01/errata.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity. 2019. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2019/home.htm (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management. 2010. Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. 2010. Available online: https://www.opm.gov/fevs/public-data-file/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management. 2011. Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. 2011. Available online: https://www.opm.gov/fevs/public-data-file/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management. 2012. Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. 2012. Available online: https://www.opm.gov/fevs/public-data-file/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- van Knippenberg, Daan, Carsten K. W. De Dreu, and Astrid C. Homan. 2004. Work group diversity and group performance: An integrative model and research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 1008–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Warren E., Kamalesh Kumar, and Larry K. Michaelsen. 1993. Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal 36: 590–602. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, Andrew B., Soo-Young Lee, Taesik Yun, and Chan Su Jung. 2010. Collaborative behavior and the performance of government agencies. International Public Management Journal 13: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Katherine Y., and Charles A. O’Reilly III. 1998. Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior 20: 77–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, Lois Recasino, and Mary Tschirhart. 2000. Examining empirical evidence on diversity effects: How useful is diversity research for public-sector managers? Public Administration Review 60: 386–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Robert E., and Edwin A. Locke. 1990. Goal setting and strategy effects on complex tasks. In Research in Organizational Behavior. Edited by Barry M. Staw and Larry L. Cummings. Greenwich: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Bradley E. 2001. Public-sector work motivation: A review of the current literature and a revised conceptual model. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11: 559–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Bradley E. 2004. The role of work context in work motivation: A public sector application of goal and social cognitive theories. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 14: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Bradley E., and Brian S. Davis. 2003. Job satisfaction in the public sector: The role of the work environment. American Review of Public Administration 33: 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Kaifeng, and Anthony Kassekert. 2010. Linking management reform with employee job satisfaction: Evidence from federal agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20: 413–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 615,084 | 51.4 |

| Female | 519,378 | 43.4 |

| Missing | 62,773 | 5.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Minority | 375,034 | 31.3 |

| Non-Minority | 734,367 | 61.3 |

| Missing | 87,834 | 7.3 |

| Age | ||

| 29 and Under | 63,506 | 5.3 |

| 30–39 | 183,022 | 15.3 |

| 40–49 | 328,601 | 27.4 |

| 50–59 | 407,891 | 34.1 |

| 60 and Older | 143,107 | 12.0 |

| Missing | 71,108 | 5.9 |

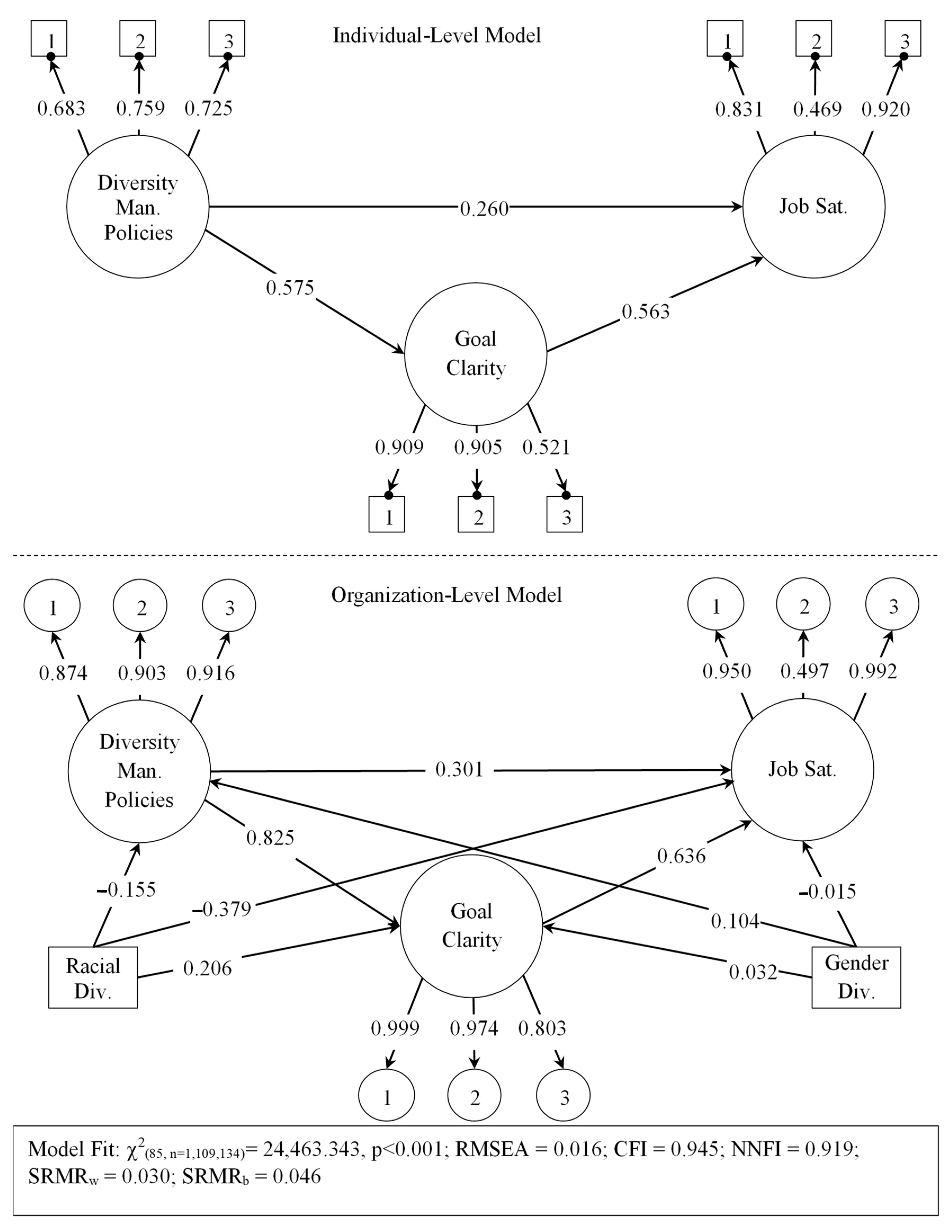

| Individual Level Model | ||||

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Goal Clarity | 0.563 | 0.014 | 40.135 | 0.000 |

| Diversity Management Policies | 0.260 | 0.015 | 17.770 | 0.000 |

| Goal Clarity | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Diversity Management Policies | 0.575 | 0.017 | 34.509 | 0.000 |

| Organization Level Model | ||||

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Goal Clarity | 0.636 | 0.057 | 11.172 | 0.000 |

| Diversity Management Policies | 0.301 | 0.061 | 4.908 | 0.000 |

| Goal Clarity | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Diversity Management Policies | 0.825 | 0.024 | 34.814 | 0.000 |

| Goal Clarity | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Racial/Ethnic Diversity | 0.206 | 0.038 | 5.419 | 0.000 |

| Gender Diversity | 0.032 | 0.030 | 1.055 | 0.291 |

| Diversity Management Policies | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Racial/Ethnic Diversity | −0.155 | 0.065 | −2.356 | 0.018 |

| Gender Diversity | 0.104 | 0.051 | 2.046 | 0.041 |

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST\S.E. | p | |

| Racial/Ethnic Diversity | −0.086 | 0.032 | −2.677 | 0.007 |

| Gender Diversity | −0.015 | 0.021 | −0.684 | 0.291 |

| Job Satisfaction | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST/S.E. | p | |

| Supervisory Status | 0.011 | 0.003 | 3.851 | 0.000 |

| Age Group | 0.030 | 0.002 | 13.714 | 0.000 |

| Pay Category | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.915 | 0.360 |

| Federal Tenure | −0.027 | 0.002 | −11.316 | 0.000 |

| Goal Clarity | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST/S.E. | p | |

| Supervisory Status | 0.055 | 0.005 | 11.358 | 0.000 |

| Age Group | 0.028 | 0.003 | 10.210 | 0.000 |

| Pay Category | −0.042 | 0.004 | −11.020 | 0.000 |

| Federal Tenure | −0.026 | 0.004 | −6.504 | 0.000 |

| Diversity Management Policies | ||||

| EST | S.E. | EST/S.E. | p | |

| Supervisory Status | 0.150 | 0.006 | 24.921 | 0.000 |

| Age Group | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.303 | 0.762 |

| Pay Category | 0.074 | 0.011 | 6.609 | 0.000 |

| Federal Tenure | −0.103 | 0.004 | −25.878 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stazyk, E.C.; Davis, R.S.; Liang, J. Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030077

Stazyk EC, Davis RS, Liang J. Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030077

Chicago/Turabian StyleStazyk, Edmund C., Randall S. Davis, and Jiaqi Liang. 2021. "Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 3: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030077

APA StyleStazyk, E. C., Davis, R. S., & Liang, J. (2021). Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030077