Abstract

Organisations have shifted from traditional beliefs to the incorporation of agile methods for attaining high levels of performance through its established goals and objectives. Emotional intelligence (EI) is envisaged to contribute to the achievement of higher levels of performance. With the current global economic crisis and the pandemic situation, it has become very critical to achieve higher levels of performance with limited resources. Countries confront challenges by way of attaining a higher level of emotional maturity and realisation in order to sail through the current economic storm. The Administrative and Diplomatic Officers (ADOs) are seen to shoulder a heavy responsibility in materialising this shift. This study analyses the impact of EI on organisational performance (OP) in the Malaysian public sector. A survey instrumentation was distributed to 700 ADOs based in Putrajaya, within five selected ministries, obtaining 375 valid responses. The results attained, analysed using the SMART-PLS method, affirm the significant positive effect of EI on OP, suggesting the need for an increase in the EI of civil servants by including EI indicators and measures in the areas of recruitment, learning and development, workforce planning, succession planning, and organisational development. EI should actively be adopted to increase awareness and maturity, which would thus enable civil servants to embrace the current challenging agile environment.

1. Introduction

The performance of an organisation is related to the magnitude of output in meeting its goals and objectives to produce the desired results. Organisations analyse outputs based on their financial position, value to their stakeholders, and comparative performance relative to peer organisations. On a higher level, the performance of a country is often related to the strength of the public sector, which in turn relies on the capabilities and competencies of the public administrators. In a global context, the comparative performance of the respective countries are mainly determined by their global economic position. Individuals with higher emotional intelligence (EI) display prosocial behaviours, indirectly acquiring the traits to behave appropriately in interpersonally challenging situations (Martin-Raugh et al. 2016). The ability of the public administrators to steer and facilitate economic growth through respective channels and ministries require special attention. In addition to their role as advisors that steer and guide politicians in policymaking, they assist in the implementation and administration of the policies. With their role as civil servants deemed as a very critical one, public administrators should consist of highly mature and capable personnel of high calibre and integrity. In addition to the expectations of having widespread knowledge and awareness in public law and policies, and the capabilities of maintaining a healthy relationship with the public, civil servants are excpected to possess high levels of EI (Lee 2018). The government administration, which provides public services, need to embrace the agile environment positively during these unprecedented times of global economic crisis, topped by the pandemic situation. Despite the stressful work environment created by the Covid-19 pandemic, employees with high EI have displayed the highest levels of work performances and the least counterproductive work behaviours, in contrast to those with lower EI who exhibited higher stress levels at work (Sadovyy et al. 2021). Covid-19 has had a significant impact on working conditions, the mental health of individuals, social interactions between individuals, groups, and organisations, thus leading to a “psychological pandemic”; consequently, various mediations are expected to be implemented in order to improve this situation (Giorgi et al. 2020). Since EI has been established as a significant psychological determinant in the workplace, it may have a contributing role in the Covid-19 pandemic state. The growing attention on digitalisation in the public sector requires an effective and efficient public service delivery (Veerankutty et al. 2018). Therefore, the EI of civil servants has an imperative role in strengthening the performance of governmental organisations during such times.

EI is the ability to perceive, access, and generate emotions to assist in the generation of corresponding thoughts; it is the ability to understand emotions and the knowledge they generate, and to further regulate emotions in an attempt to promote intellectual growth (Goleman 1995). Managers with higher EI qualities demonstrate strong moral behaviour, implying positive professional activity at the workplace (Angelidis and Ibrahim 2011). Effective leaders are good communicators, have an optimistic attitude, are flexible in their thoughts, and are emotionally balanced (Mittal and Sindhu 2012). In the context of public service, EI can be defined as the ability to deal amicably with emotions at the workplace. It consists of social awareness, self-awareness, self-management, and relationship management (Goleman 1995). Studies in various settings have established that EI fosters effective leadership (McCleskey 2014). A significant amount of research involving public administrators has been conducted in the education sector, but with limited research in the public sector (Lee 2018; Majeed et al. 2017; Arfara and Samanta 2016; Guy and Lee 2015). Puertas Molero et al. (2019) assert that EI is a key influence in the educational environment, contributing to the psychological well-being of educationists. This study intends to bridge this gap by highlighting the influence of EI on organisational performance (OP) in the public sector, particularly based on public administrators in Malaysian public service. According to Kerr et al. (2006), integrating EI as an intervention tool in the recruitment and selection as well as the training and development processes of managerial personnel endorses the effectiveness of leadership skills. The attitude of employees in the service industry towards customers has profound long term and short-term impacts, as it has been proven that employees who are attentive, courteous, and responsive are integral components in public service (Agus et al. 2007). As leadership emerges as a complex and forceful element, developing a global mindset and attitude requires an evidence-based strategic framework (Avolio et al. 2009). Findings reveal that EI is highly effective in predicting organisational commitment, subsequently encouraging a positive OP (Adeoye and Torubelli 2011).

The Malaysia Productivity Report (MPR) issued by Malaysia Productivity Corporation in 2019 (Malaysia Productivity Corporation 2019) highlighted a growth of 2.2% in labour productivity. However, the productivity of domestic sectors in Indonesia and Thailand recorded a high of 3.8% and 4.5% respectively (Malaysia Productivity Corporation 2019). In comparison, this indicates Malaysia is lagging in competitiveness amongst its neighbouring countries. One of the solutions outlined in the Malaysian Productivity Blueprint, contained in the MPR (Malaysia Productivity Corporation 2019), was to “restructure the workforce by raising the number of high-skilled workers, (while) tightening the entry of low-skilled workers and meeting future economic demands in the labour market” (Malaysia Productivity Corporation 2019, p. 17). The fact that the public sector is known to be a stimulus for growth and the various performance indicators of the country, including that of the private sector output, has led to new research that examines the OP of the public administration. A survey questionnaire was utilised to collect relevant information from the public administrators in Malaysia. Data analysis was conducted using the SMART PLS software. Findings show a positive and significant effect of EI on the OP. Survey findings indicate that the inclusion of EI as part of employee performance assessment in organisations contribute to an overall higher level of productivity.

2. Literature Review

Employees in the public sector, especially the public administrators, are usually faced with emotionally intense duties and responsibilities, making EI an important factor (Lee 2018). Public service jobs mostly involve work demands that are emotionally intense (Guy and Lee 2015). EI is an important factor that provides improved capabilities for achieving organisational goals and job objectives, inducing better teamwork through cooperation and trust (Arfara and Samanta 2016). Emotionally intelligent employees tend to have a positive mindset, appear more contented, dedicated, and loyal to their profession and organisation, which in turn creates a conducive environment that effectuates improved job performances (Miao et al. 2017). Burnout at the workplace can be decreased with the ability to manage and regulate one’s emotions (Arfara and Samanta 2016). Employees with high EI levels have been found to have a lower burnout rate in performing tasks (Sanchez-Gomez and Breso 2020). The absence of employee burnout while performing a task encourages employee engagement, allowing for consistent focus on the task at hand, thus contributing to a higher level of motivation in performances. The leaders in public management and administration should consider traits of EI as important elements in the characteristics of personnel recruited into the public sector, mainly in terms of self-awareness and regulation (Lee 2018; Arfara and Samanta 2016). The perceived influence of EI implicates its inclusion in training and development initiatives (Guy and Lee 2015), which would help organisations to enhance the level of commitment by means of the improved individual behaviour (Majeed et al. 2017) and team performance of emotionally strong and consistently motivated team members (Sithambaram et al. 2021). EI determines the performance of employees; a high EI level produces high performances, while a lower level of EI breeds low performers (Law et al. 2004; Van Rooy and Viswesvaran 2004; Mayer et al. 2012; Cuéllar-Molina et al. 2019). In a broader perspective, Alkahtani et al. (2021) argued that culture is supposed to play an important role in the emotional capability of employees. Having been blended into organisations over time, organisational culture is difficult to alter over short durations.

Control of emotions, perceptions, adjustments, self-management, interpersonal effectiveness, and discussion skills are traits of EI in successful organisations (Carnevale et al. 1988; Cherniss 2001; Rathore et al. 2017). Organisations that are aware of EI invest in relationship, empathy, and problem-solving training programmes. These traits are utilised to resolve situations and communicate requirements in a clear and structured way that is well received (Pearman 2011). “EI as a moderator increases positive work attitudes, altruistic behaviour, and work outcomes and moderates the effect of work-family conflict on career commitment” (Carmeli 2003, p. 5). However, it does not moderate job satisfaction amongst senior managers in local government authorities. Findings reported a positive and significant relation of EI to job satisfaction (β = 0.32, p < 0.01), high effective commitment to the organisation (β = 0.23, p < 0.01), high commitment to their career (β = 0.34, p < 0.01), effectively control of work-family conflict (β = −0.31, p < 0.01), and higher levels of altruistic behaviour ((β = 0.54, p < 0.001), while it is negatively related to withdrawal intentions from the organisation (β = −0.20, p < 0.01), resulting in managers with higher EI performing the job better (β = 0.32, p < 0.01) (Carmeli 2003). These findings suggest that EI drives employees to be more involved emotionally, leading to better OP. Mulla (2010) conducted EI research utilising the ability model and the Wong and Law’s (2002) questionnaire instrumentation. The results indicated the lack of a significant relationship between EI and job performances. The findings revealed that interpersonal interaction, being a characteristic requisite in a job, moderated the relationship between EI and performances at work, concluding that individuals with high EI levels have excellent communication skills (Mulla 2010). The importance of the effect of EI on OP is highlighted specifically in the role of interpersonal communications in service industries (Wong and Law 2002; Mulla 2010). However, the findings differ due to the EI dimensions used in the questionnaires of the respective studies. “Schutte’s self-report 33-item questionnaire is unidimensional, consisting of optimism/mood regulation, appraisal of emotions, social skills, and utilisation of emotions is an addition to an overall EI measure” (Saklofske et al. 2003, p.1031). As this scale encompasses a wider definition, it contributes to the difference in the findings on EI and job performances of both studies (Shi and Wang 2007).

EI and recruitment have a positive significant relationship (Marzuki 2012). A candidate with high EI increases organisational value (Blank 2008). As such, the ability to determine candidates who are emotionally intelligent at the onset of recruitment would reduce the need for EI training, providing an opportunity for the organisation to focus on alternative training areas. Quantitative studies on sales professionals indicate an influential positive inter-relationship between EI, decision-making, and the consolidation of information. An analysis on dimension reveals that understanding (p < 0.05) and managing emotions (p < 0.05) have a positive relationship with the sales income (Kernbach and Schutte 2005). EI influences the relationship between customer orientation and sales performance, resulting in a more effective job performance (Kim et al. 2009). The demographic data on EI studies reveal that age has a negative relationship with EI levels; education level has a significant positive effect on EI; marital status has no significant relationship with the level of EI; and female employees tend to have higher levels of EI (Hussain-Rahim and Malik 2010). Research affirms that emotionally intelligent employees contribute to a more effective work environment by remaining positive, even in a negative situation (Subhashini 2008), contributing to higher levels of job satisfaction, loyalty, and commitment (Miao et al. 2017). This claim is in line with Goleman’s (1995) research that emphasised the importance of self-awareness in understanding the impact of moods and emotions in job performance. Additionally, to ensure optimum performance and remain competitive in the market, employers are encouraged to maximise employees’ performance (Singh 2007). Researchers highlight the inclusion of EI as a mediator in occupational stress due to its positive and significant correlation with job performance (β = 0.27, p < 0.01) (Ismail et al. 2009). Emotionally intelligent individuals have greater understanding of the causes of stress (Miao et al. 2017). Emotional labour and job stress are mediated by EI, as an inverse relationship between job performance and stress exist, where an increase in stress will decrease the performance of employees in a task (Cano and Sams 2009).

EI is an important element that contributes to work performance (Sanchez-Gomez and Breso 2020) by allowing people to manage “their emotions to cope effectively with stress, perform well under pressure, and adjust to organisational change” (Lopes et al. 2006, p. 135). As such, it proves that those with higher EI levels have higher stress tolerance levels. An individual who possesses a high EI level has the ability to demonstrate this, thus improving in their social and behavioural competency at work. A quantitative study by Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler (2010), examining the relationship between EI and organisational politics, concluded that both rational and emotional elements play an important role in managerial considerations in public administration. Muir (2006) emphasised incorporating EI in training sessions conducted in the workplace. Freshman and Rubino (2004) focused on health care administration applications to EI components, stressing the role of EI in various customer orientated organisations (Deshpande et al. 2005). The delivery of these services also ensures the provision of increased quality (of service) to the users or customers. An individual performing a task at the cognitive level does not require EI skills, as opposed to individuals performing in a team setting (Druskat and Wolff 2001; Jordan and Troth 2004; Hess and Bacigalupo 2011). EI peers and managers in an organisation have better relationships, specifically in areas related to cooperation and conflict management (Clarke 2010).

On the contrary, some results of empirical studies do not support relationships with EI. A range of literature reviews have concluded that EI has no relationship with perceived leadership effectiveness, perceived leadership outcomes, and transformational leadership (Cavazotte et al. 2012). Additionally, the difficulties in measuring EI is a key problem, which hinders the development of a strong scientific base for EI (Matthews et al. 2012; Burcea and Sabie 2020). This has also been highlighted by Miao et al. (2017), who argued that incorporating EI as part of personality and cognitive measures can improve the analysis of job contentment, organisational commitment, and employee retention. Although there are a range of literature with weak evidence, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that EI is an important element in leadership effectiveness (Md-Sahidur-Rahman et al. 2020). Despite these empirical constraints, vast studies acknowledge that emotions are embedded in interpersonal exchanges, and individuals differ in their ability to manage and perceive emotions, emphasising the importance of emotions in leadership research (Belfanti 2017).

3. Hypothesis

Findings have indicated a positive correlation between EI, performance, and leadership (Radhakrishnan and Udaya-Suriyan 2010; Cherniss 2001; Harms and Credé 2010; Vivian-Tang et al. 2010; Shipley et al. 2010; Hur et al. 2011; Lopez-Zafra et al. 2012; Boyatzis et al. 2012). EI is closely associated with transformational leaderships as its baseline components consist of empathy, self-confidence, and self-awareness, creating a systematic moral alteration in individuals and communities existing in social systems (Alston et al. 2010; Riaz and Haider 2010). Additionally, EI mediates the relationship between performance and leadership effectiveness, leading to effective OP (Hur et al. 2011). Empirical evidence show that EI has a significant positive relationship with OP; accordingly, this research studies the direct effect of EI on OP in the Malaysian public administration. It is hypothesised that EI has a significant positive effect on OP, particularly within the public sector.

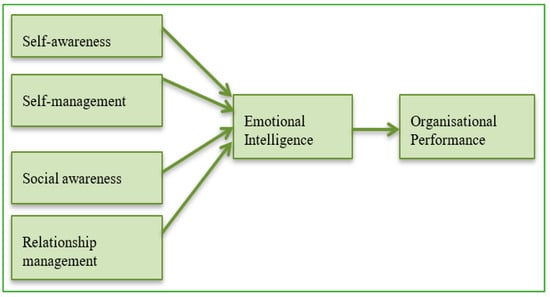

Figure 1 displays the conceptual framework of EI used in this study, comprising the effect of “self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management” on OP.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for EI and OP (adapted from Kaplan and Norton 2005; Goleman 1995; Zeitz et al. 1997).

The theory of competence by Goleman used in this research integrates emotional, social, and cognitive intelligence competencies, which results in a theoretically coherent framework for organising the assessment and development of talent in the workplace (Emmerling and Boyatzis 2012). It advocates the ability to utilise emotional information, social intelligence competency, and cognitive intelligence to recognise, understand, and create awareness in the analysis of knowledge and environments, which encourages superior performance (Goleman and Boyatzis 2008). Goleman’s (1995) theory drives performance and EI in this model, which is able to predict the behavioural patterns in work and life, and its outcomes that are derived from the consequences of these patterns (Boyatzis 2001). Studies on OPs are vital due to the various internal and external challenges faced by organisations.

4. Methods

4.1. Sampling

In this research, the unit of analysis is the Administrative and Diplomatic Officers (ADOs) of the Malaysian civil service consisting of Grade 41 (entry level) positions and senior officers at Grades 44, 48, 52, and 54 based in Putrajaya, the administrative capital of the federal government of Malaysia. ADOs are mainly involved in the planning, formulation, and implementation of government policies in relation to various ministries; they formulate the main government policies that are implemented at the national, international, and global scales. As the sampling frame for all such officers were not accessible at the Public Service Department, a purposive sampling method was employed. G*Power 3.1.9 was used to guide in the minimum sampling size required (Faul et al. 2009). As recommended by Hair et al. (2014), with the power of 0.8 and an effect size of f2 = 0.15, plus the predictor of the variable with the highest value of 5, the minimum sample was determined as 76. In order to have a more consistent model for this research, Ringle et al. (2014) highly recommended doubling or tripling this number, recommending between 152 and 228 respondents. Seven hundred respondents were targeted based on their job role and grade (public administrators), and their expected level of capabilities in providing the required feedback for analysis. A total of 375 prospects were available and agreed to commit to complete the questionnaire. This number is higher than the proposed maximum sampling of 228. The representatives of the five selected ministries were satisfied with this representation.

4.2. Data Collection

A survey questionnaire was developed, adapted from various scholars (Salovey and Mayer 1990; Goleman 1995; Zeitz et al. 1997) as shown in Table 1, which was used as the instrumentation to collect data. The full reference of the 26 EI items and 20 OP items used in the questionnaire are listed in Table A1 and Table A2, respectively, in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Development of the questionnaire (adapted from Salovey and Mayer 1990; Goleman 1995; Zeitz et al. 1997).

The EI questionnaire consisted of 26 items and the OP questionnaire consisted of 20 items. This measurement tool was chosen as it provided the capabilities of capturing a broader spectrum of dispositions related to emotions and social conditions at the workplace (O’Connor et al. 2019). The questionnaire was developed using close-ended questions. A five-point Likert or Likert-type scale employed on 46 items were utilised, using a combination of the following options:

- Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, and Consistently;

- Strongly Disagree, Somewhat Disagree, Neither Agree Nor Disagree, Somewhat Agree, and Strongly Agree.

The researchers briefed, clarified, and explained the objectives of the survey to the representatives during a face-to-face meeting. The researchers had several discussions with the administrative executives, where the administrative executives jointly selected five ministries within the administrative capital of Malaysia (Putrajaya) to be included for the collection of survey responses. The decision was made based on the role, responsibilities, level of impact on public policies, overall performance of the ministries, and their level of economic impact on the government. The administrative executives requested for anonymity of the selected ministries, thus restricting the researchers from completing a comparison of performances between the five selected ministries.

As government departments are controlled areas, it was not possible for the researchers to enter their premises to interview the potential respondents themselves. As a result, a face-to-face meeting was held with key representatives from the five ministries to brief them on the objectives and expectations of the survey in August 2017, when the questionnaires were handed to them. The representatives consequently distributed the survey questionnaires to the selected respondents, giving them a grace period of 4 weeks. Follow-ups by the researchers with the representatives were conducted on a fortnightly basis to check on the status of the survey responses. Questionnaire completion was closed by the end of March 2018, and 375 completed questionnaires were collected from the representatives of the five ministries in April 2018. To ensure the confidentiality of responses, the respondents were provided with a sealable envelope, requiring them to seal their individual completed questionnaires before returning them to the representatives. This process allowed their responses to remain confidential and anonymous. The response rate was at 53%.

The 375 questionnaires returned to the researchers were found to be completed properly, as per the initial expectations of the study. The data from the questionnaires were tabulated in a spreadsheet, and subsequently entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 software produced by IBM Corp in Armonk, New York, USA, first released in 2015. The next section of data analysis provides information on the steps taken to further refine the data. Data from these studies were collected from Malaysian Administration and Diplomatic Officers. Four EI perspectives will be analysed to determine their effect on OP. The results of this study are limited to the public administration function based in Putrajaya, Malaysia.

4.3. Data Analysis

The seven demographic items of the questionnaire were gender, age, marital status, number of children, level of education, years of working experience in their current job, and current position/grade held in the organisation, as shown in Table 2. Upon analysis of gender, it was noted that 61.9% were female employees and 38.1% were male employees, which apparently reflects the common scenario in the Malaysian public sector. This shows a gender imbalance in the respondents to the survey questions. The largest age category comprises those 31–40 years of age, which represents 48.3%of the overall sample. The next largest group of respondents (29.3%) is between 41 and 50 years of age.

Table 2.

Demographics of the Survey Respondents.

Married respondents constitute 82.4%of the total sample. The number of respondents who are single constitute 17.1%of the total respondents. Most of the respondents have children, with a majority of respondents having two children, comprising 37.0% of the total sample. Respondents who are married and without any children constitute 7.4%. In analysing the educational level, a majority of the respondents (78.7%) have a bachelors’ degree, which most likely made it easier for them to comprehend the contents and language of the questionnaire and provide valid and correct responses. This is considered advantageous as they exhibit the competencies in understanding the expectations of the survey.

In terms of work experience, respondents with 6–10 years of experience constitute most of the sample at 43.5%, which is much higher than those with less than five years, or more than 15 years of work experience. The varying levels of years of work experience of the respondents assisted in providing different perspectives in the responses, which is deemed to afford added value to the analysis of the overall data. From the perspectives of position, the respondents from grade M44 are the largest in proportion (44%) to have answered the questionnaires. Only one person belonging to Grade 54 participated in this study.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to ascertain the effect of EI on OP. SEM is a tool that is used for testing the overall fit of the model, including the structural model simultaneously (Gefen et al. 2000). SEM is a popular multivariate technique that is used in evaluating the overall linkage between components and the linkage that exists between a component and its corresponding measures. Two main approaches are commonly used in SEM: a component-based approach being a partial least square (PLS-SEM), and a co-variance-based approach (CB-SEM) (Fornell and Bookstein 1982; Marcoulides and Saunders 2009; Wetzels et al. 2009). The two methods differ by their underlying statistical assumptions, which are fit analysis models. This research utilises the partial least square approach to test/predict the theoretical model derived from the literature, and it is not geared towards the identification of the model that would fit best (Sosik et al. 2009). There are two steps in assessing the data, the first being the assessment of the measurement model that involves internal consistency, indicator reliability, convergent validity, and the discriminant validity of the measurement model for EI and for OP. The second step is the assessment of the effect of EI on OP via the structural model. The overall measurement model of EI was evaluated using relevant variables consisting of self-awareness (emotional self-awareness (ESA) as an indicator), self-management (achievement orientation (AO) and emotional self-control (ESC) as indicators), social awareness (empathy (EMP) as an indicator), and relationship management (influence (INFL) as an indicator).

Table 3 shows that all components of the EI model have an acceptable level of Average of Variance Extracted (AVE), which are between 0.502 (self-awareness) to 0.559 (relationship management). It shows that the outer loading of variables in the initial and modified measurement model fulfils the requirement of ≥0.5, except for ESA3, ESA4, ESA5, AO4, AO5, AO6, EMP4, EMP5, EMP6, INFL3, and INFL5. As a loading of ≤0.5 for an item does not contribute to the construct of the variable (Hair et al. 2017), these items were subsequently excluded/omitted. The other important requirement to fulfil convergent validity is the composite reliability (CR). All indicators of EI have CR levels that are acceptable (0.828–0.842), and can be broken down as follows: ESA (0.828), INFL (0.829), AO (0.840), and EMP (0.842). The composite reliability ranges from 0 to 1, whereby the higher the value, the higher the reliability level. Composite reliability below 0.6 indicates a lack of internal reliability and consistency (Hair et al. 2017). The acceptable composite reliability value for an exploratory research is between 0.6 and 0.7 (Hair et al. 2017). As the items in Table 3 fulfil the conditions of convergent validity, we will next look at the construct validity of the measurement model for OP to determine if it fulfils these requirements as well. The overall measurement model of OP was evaluated using relevant variables that consisted of learning and growth (LG), internal process (IP), financial perspective (FP), and stakeholder perspective (SH). The overall measurement model of this questionnaire for OP consists of the above subscales, which are also measured using Smart-PLS. The measurement model determines the extent to which these four constructs measure the variables (items), as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Construct Validity of the Measurement Model for Emotional Intelligence (EI).

Table 4.

Construct Validity of the Measurement Model for Organisational Performance (OP).

As the outer loading for the measurement of the modified model was ≤0.5 for LG1, LG2, LG3, IP3, IP4, IP5, FP1, FP3, SH1, SH4, and SH6, they were omitted. A loading of ≤0.5 for an item does not contribute to the construct of the variable (Hair et al. 2017). If the deletion does not influence content validity, and the value of the composite reliability does not increase, with the outer loading ≥0.4, then the item need not be omitted (Hair et al. 2017). This applies to LG2, FP4, and SH1. Table 4 displays OP items with an acceptable level of AVE, between 0.514 (FP) and 0.600 (LG). All items of OP have an acceptable level of CR (0.750–0.808); FP (0.750), IP (0.765), LG (0.817), and SH perspective (0.808). As the items in Table 4 fulfil the condition of convergent validity, the construct validity of the measurement model for OP is then determined if it fulfils these requirements as well.

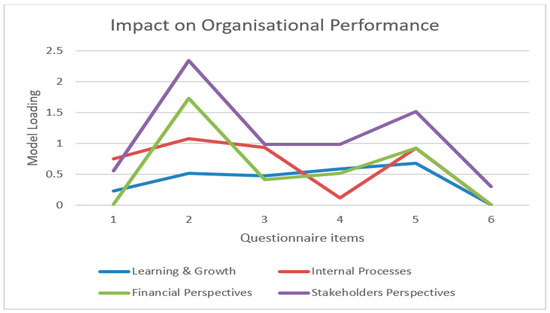

Based on the analysis in Figure 2, the “Stakeholder Perspectives” draws the greatest concern for the ADOs, followed by the “Financial Perspectives”, indicating that the performance of an organisation is impacted by the perceptions of the stakeholders and the financial standings of the organisation. “Internal Processes” and “Learning and Growth” draw moderate concerns; however, these items should not be neglected.

Figure 2.

Areas of concern regarding the impact on Organisational Performance (OP).

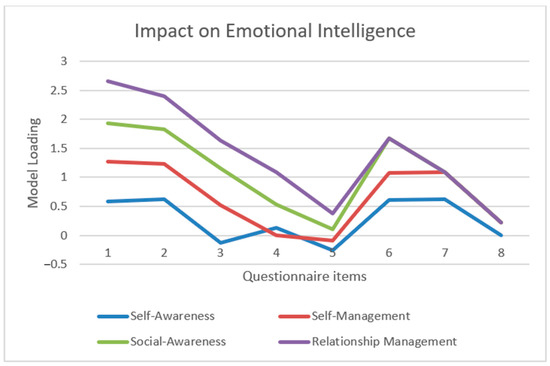

Based on Figure 3, from the perspectives of EI, the survey respondents gave high importance to “Relationship Management” and “Social Awareness”. This indicates that good relationship management with the stakeholders and a high level of awareness on social elements promote a higher OP rate. “Self-Awareness” and “Self-Management” are also crucial in maintaining a high level of OP, which should not be neglected. The next step was to ascertain the effect of EI on OP. This was achieved by assessing the structural model. Smart PLS 3.2.7 was able to test the significance level and generate t-statistics for all paths by means of bootstrapping. Based on the results generated for the t-statistics output, the significance level of each relationship was determined.

Figure 3.

Areas of concern regarding the impact on Emotional Intelligence (EI).

Table 5 displays the results on the path-coefficients, observed t-statistics, and significance level for the entire hypothesized path, which determines the acceptance of the proposed hypothesis.

Table 5.

Structural Model—Direct Effect Results of Emotional Intelligence (EI) on Organisational Performance (OP).

The bootstrapping procedure was used to generate t-samples, with 5000 resamples to assess the hypothesis. Firstly, the effect of EI on OP was examined. EI (β = 0.67, p < 0.05) had a positive and significant effect on OP, thus being able to moderately explain 26 percent of the variance of OP. Hair et al. (2017) advised researchers using PLS-SEM to depend on the model’s predictive capabilities to assess the model’s quality, instead of the global goodness of fit. The predictive capability of this model is shown in Table 5. In addition to evaluating the R2, the effect size, f2, determined the change in the R2 value when a specified exogenous construct was excluded from the model, and to the extent of its importance to the endogenous constructs. The determination of effect size is vital as both the substantive significance (f2) and the statistical significance (p-value) reflect the strength of the model (Sullivan and Feinn 2012). The guidelines for assessing f2 are the values of 0.02, which signifies a small effect; 0.15, which signifies a medium effect; and 0.35, which signifies a large effect of the exogenous latent variable (Cohen 1988). The effect size of less than 0.02 can be considered as having no effect. Table 5 further indicates that the exclusion of EI had an important effect on OP (f2 = 0.85). The Q2 value shown in Table 5, “determined by the blindfolding procedure, predicts the relevance of the structural model in predicting the indicators of endogenous constructs” (Hair et al. 2014, p. 265). This technique omits part of the data matrix, and the estimated models are used to forecast the omitted portion. The blindfolding technique is suitable for reflective measurement models and can be used for a single or multiple items (Hair et al. 2014). “The value of Q2 > 0 has sufficient predictive relevance, and the value of Q2 < 0 shows a lack of predictive relevance” (Fornell and Cha 1994, p. 54). As shown in Table 5, Q2 = 0.06, indicating that there is sufficient predictive relevance for EI on OP.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study have important implications as they reveal that the EI of the ADOs has a positive and significant direct effect on OP (β = 0.67, p ≤ 0.05). The results are consistent with previous findings where EI, comprising self-awareness, self-management, social-awareness, and relationship management, has a positive effect on OP (Kerr et al. 2006; Agus et al. 2007; Avolio et al. 2009; Adeoye and Torubelli 2011; Angelidis and Ibrahim 2011; Mittal and Sindhu 2012; McCleskey 2014; Martin-Raugh et al. 2016; Baczyńska and Thornton 2017; Bozionelos and Singh 2017). Findings by Pekaar et al. (2018) highlighted that the appraisal of emotions as part of EI is more effective in predicting OP, suggesting that analysing the skills of public administrators from the perspective of EI will allow public services to be equipped with a more capable administrative team. This team will have greater capabilities in producing a higher level of OP, navigating the organisation towards achieving greater success. In the context of this study, emotionally intelligent ADOs are expected to influence organisational performances, as the result of the study indicates a strong inter-relationship. Higher levels of EI will directly produce higher levels of OP.

The positive significant effect of EI on OP in public administration assists in advancing the organisation’s objectives, leading to an improved delivery of services within the organisation and its stakeholders. EI is envisaged to generate a catalysing effect by means of its influence on the intellectual capabilities of the employees, leading to the achievement of a competitive advantage. The positive significant effect of EI on learning and growth allows the ADOs to have a better sense of control of their learning capabilities, leading the self-confidence of ADOs in achieving the organisation’s objectives. An individual who has a high level of self-awareness is expected to know their own limitations, as well as the weaknesses and limitations of their team members and department, thus enabling them to analyse training needs and acquiring skills and new knowledge to foster greater levels of performance. Teamwork requires EI management, as team members are required to comprehend and respond positively to team goals; therefore, managing the emotions of the team members is seen to be an important element in promoting OP (Sithambaram et al. 2021). ADOs with high levels of self-awareness possess the experience and opportunity to acknowledge the processes and behaviours which are conducive for them to fulfil their responsibilities. The experience gained will encourage them to be flexible and creative in problem solving, in addition to being effective in decision-making.

The positive significant effect of EI on OP enhances the internal processes, which is one part of OP. ADOs who liaise effectively with colleagues, relevant stakeholders, and the public will be able to encourage their team and obtain productive and constructive feedback, creating an avenue for enhancing and improving the processes. This includes feedback through social media such as websites, messenger applications (such as WhatsApp, Viber, MS-Messenger, Telegram, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) and other forms of communication that aim to improve the OP of the public administrative function. The challenges faced by the ADOs in their workplace require the ability to make a swift search for appropriate information for decision making, recognising stakeholders’ state of emotions and utilising the information obtained appropriately by accessing its nature, thoroughness, reliability, and appropriateness in resolving public issues. The information and feedback provided by the customers will assist in making decisions at the international level when the senior officials or the ministers attend conferences, meetings, and seminars representing Malaysia. Hence, they must have the ability to communicate with their superiors, peers, subordinates, and the public in such a way as to achieve the set goals and to attain the desired effect consisting of changes in behaviour, thoughts, ideas, and attitudes. The ADOs in this context of relationship management are expected to influence and tactfully convince stakeholders, while ensuring the needs of the public are addressed.

Social awareness in the context of EI discloses a positive significant effect on OP, revealing that the ADOs are able to empathise with the needs of the public. Communication with the public provides them with an opportunity to directly recognise the issues, needs, and challenges faced by the public. This enables them to implement the relevant policies that reduce the burden of the public. The ability to empathise creates a sense of urgency in fulfilling the needs of the public, leading to accelerated actions in resolving the issues at hand, having a positive effect on OP. Emotionally intelligent ADOs who self-manage their emotions positively are able to respond appropriately to public issues. This creates a positive work ethic in the professional environment, yielding an increase in OP. The positive significant contribution of EI to OP reveals that ADOs are afforded an environment where rewards and recognition are given priority, leading to a better work situation. EI, practised by the ADOs, create an opportunity to overcome and achieve goals and objectives, leading to effectiveness in OP that directly leads to better rewards or recognitions as the needs of the stakeholders are achieved. This cycle creates motivation amongst the ADOs, paving the way for better OP that directly focuses on achieving organisational goals to balance the needs of the stakeholders and the public administrators.

Based on Figure 2 and Figure 3, which show high perceived values for stakeholders and financial perspectives for OP, and social awareness and relationship management for EI, we conclude that the Malaysian government, through its ADOs, should give importance to these areas. The public servants should have high social awareness in terms of knowing the issues and problems faced by the public, and the correct ways to address the issues. They should also create a good relationship with their main customer, the public, who can be classified as the most important stakeholder. By encouraging and promoting these EI values, the organisation will be able to obtain a higher level of performance. This will in turn increase the level of public trust in the governmental function, which will in turn increase the financial position of the organisation through a higher level of compliance and adherence to the government policies. Next in importance are the investors—stakeholders who establish the financial means in the country for domestic and international trade. With a high level of EI, the ADOs will be able to foster good relationships with them, encouraging higher investment values as they gain trust in the administration of the country.

There are various opportunities for enhancing the EI levels in the Malaysian civil service. This can be achieved by including EI indicators and measures in various policies in the areas of recruitment, learning and development (L&D), workforce planning, succession planning, and organisational development. During the recruitment process, in addition to assessing the candidates based on their qualifications, experience, knowledge, and skills, their emotional maturity level should also be assessed. This can be performed by including a psychometric test, requiring the individuals to answer relevant EI questions related to their emotional capabilities and behavioural aspects in various workplace settings in order to determine their EI level. As change is constant, the required EI assessment tool must reflect the most recent and relevant scenarios in dealing with emotions, in order to ensure that organisational objectives are met. The EI traits should be incorporated into the employee onboarding or induction programme and re-emphasised through L&D initiatives by incorporating EI elements into regular employee development programmes. The inclusion of EI in the context of L&D provides a platform for the exchange of conformed behaviours expected from the ADOs. An additional way of incorporating EI in the L&D policy would be to provide training to key employees who are expected to model this behaviour in their daily tasks, and train or coach the rest on being EI-conscious. The implementation of a proper L&D policy will allow the senior public administrators who are EI-savvy to mentor the new recruits, hence the opportunity to create an EI culture. Upon completing the EI training, an evaluation on its effectiveness should follow. This can be accomplished formally via feedback from superiors, peers, subordinates, and other stakeholders. It should further be included in their appraisal to encourage this behaviour and to ensure it becomes part of the work culture.

Succession planning should consider EI as an important trait of the future leaders of the organisation, not only focusing on incumbents with an excellent performance track record, but also on possessing high levels of EI based on their emotional capabilities and behavioural aspects. An EI assessment must be included in the succession planning policy. Leaders are expected to tap into their emotional intellect, to understand and be aware of the feelings and emotions of their colleagues, over and above their skills, knowledge, and experience. This can lead to better organisational success, reducing resistances from the employees. As ADOs are closer to the people on the ground, they will be the most ideal source of information for improving relevant policies affecting the economic and social development of the country. This can mainly be achieved by the implementation of EI in all dimensions, where both bottom-up and top-down approaches are utilised. In the public administration domain, organisational development remains the backbone, encompassing many facets, mainly improving the attitude and behaviour of the employees. As such, EI must be included in the organisational development policy. The assimilation of EI in organisational development policies strengthens the contribution via employees’ participation. The main objective of any organisational development initiative is to be successful in engaging employees and providing them with an opportunity to embrace change with positive contributions, apart from reinforcing procedures and processes. Employees with the ability to be aware of organisational changes and the impact these bring to the task, environment, and processes of the organisation as a whole can play the role of change agents. They can be proponents of change, simultaneously translating into organisational development. This can be achieved when EI is made a part of organisational development, ensuring there is less resistance to change. In addition, employees lack effectiveness when their thoughts, feelings, and actions differ. Leaders who differ in portraying their emotions and actions lack the ability to effectively influence employees in achieving organisational goals. The existing job rotation policy within the Malaysian civil service provides the opportunity for the ADOs to systematically move from one ministry to another. This is a good strategy for maintaining consistent inter-departmental EI levels. The results of the study, showing consistency in responses across the five ministries, reflect the impact of the job rotation strategy and the value it should rightfully have in order to maintain a consistent and high EI level throughout the Malaysian civil service. This exposure allows the ADOs to share experiences in utilising EI when dealing with different people in different settings, exposing them further to acquire an even higher level of EI, befitting them with superior leadership qualities.

In private organisations and corporate firms, performance is mainly driven by the quest to attain greater profits, driven by Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and Service Level Agreements (SLAs), supported by organisational goals and company strategies. This makes it less tedious for private corporations to achieve high levels of OP, which does not in any way discount the importance of EI. In a non-profit setting, performances are normally driven by motivational elements of leaders, political ties with other governmental organisations, and the level of competition with neighbouring countries and other nations of common trade and development avenues and initiatives. The core motivational element for performance is the total compensation package offered; however, it does not determine the level of teamwork the individual adheres to. Individual performance and OP are two very different aspects, which may not necessarily yield similar expectations and results. Therefore, it is perceived that having a high level of EI creates the probability of a higher level of performance delivered by the organisation. This concept will evidently be more critical in the civil and public services arena, particularly in a government administration setting. Governments should strive for high levels of EI, especially amongst their administrative and management teams, to garner greater levels of success in implementing policies, achieving objectives, maintaining diplomatic ties and relationship, and performing its ardent duties of providing public services, national security, economic security, economic assistance, leadership, and maintaining order.

6. Conclusions

Public sectors across various nations have adopted competency development as a key strategy of public sector reform (Belfanti 2017). Additionally, managers with emotional capabilities have been found to positively influence the organisational capacity for change, and subsequently, positively influencing OP (Sukoco et al. 2021). As such, the findings of this research may be applicable to the international arena, where it can be used in a more generic context to identify the relationship between EI and OP in other countries, especially in the public administration sector. The findings in this study show that EI positively and significantly affects OP. We hope that the results of this study will be a useful platform for future researchers to revisit and improvise the findings in relation to EI in the workplace. The precise ability to use these emotions accurately, in accordance with the various circumstances, is crucial for achieving the goals and objectives of public organisations. With the current depth and breadth of development in Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), digital era, data science, and analytics, EI is envisaged to play an even more important role in determining performance and success. Therefore, studies in EI will become increasingly essential, deemed as a very important element in the workplace. As organisations are becoming more global, and countries are becoming more tightly connected, public administrators are expected to deliver and perform on a global scale, as per the expectations of the stakeholders. It is hoped that the ADOs, as frontline managers in the public sector, will be able to contribute to the efficient and effective governance of the country. This in turn will lead to better performance of the governmental organisation. In Malaysia, this factor has been deemed even more important after the last General Election (GE), which was the 14th GE held in 2018, which experienced a major change in government leadership. This drastic shift made evident that the citizens (voters) are becoming more prudent, with renewed demands for changes in the manner the country is administered, and its objectives delivered. ADOs are required to possess a high level of EI when executing their tasks in order to be able to contribute to a higher level of OP. Individuals with a higher level of EI are deemed to be better administrative leaders in the civil service.

The call for change is also expected in the performance of the civil servants, particularly in fulfilling their responsibilities when delivering the objectives of the government, as per the expectations of the public. Being the main stakeholders, the citizens expect accountability and responsibility on the part of the civil servants, who represent the various ministries. The awareness of EI is deemed relevant and timely as it provides an opportunity for the civil servants to engage in introspection with regard to their role in the previous government, and to accept unavoidable changes, as policies and processes are transformed with the election of the new government. As civil servants are expected to be impartial, the effect of EI on OP becomes more important and relevant in achieving the objectives of the government. An increase in their performance will elevate the economy of the country as public resources are utilised efficiently. In the future, government policies need to be aligned with the need to recruit public administrators who are emotionally intelligent in order to enhance performances. The existing public administrators should be trained on the importance of EI and performance, which may be considered an up-skilling initiative. In creating an environment that emphasises EI, it is hoped that there will be a positive significant effect that can influence performances and increase the productivity of the ADOs in the Malaysian government.

The findings of this study contribute to practical and theoretical implications. From the perspective of practical implications, the findings show a positive relationship between EI and OP. EI can be included in recruitment, L&D, workforce planning, succession planning, and organisational development as part of government transformation policies across various departments, thus yielding better OP. EI should be practised by every individual and be implemented top down. Key personnel should apply this in their daily interactions and dealings with individuals in public service to further enhance OP. From the perspective of theoretical implications, researchers can further examine other indicators of EI that may influence OP. Additionally, this research can be extended to both public and private service, and within different types of organisations. Researchers may further enhance the theoretical framework. In short, this study illustrates the importance of EI at the workplace, specifically the public sector due to its diversity in policies, procedures, and the vast variety of people they interact with daily.

The global outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic saw the disruption of the way work is performed. During the many phases of the Movement Control Order (MCO) imposed in Malaysia since early 2020, the functions of the public service was performed remotely; employees were empowered to work from home (WFH) in order to reduce the proportion of the workforce at the office. The WFH concept was highly dependent on the capabilities of individuals to perform work remotely via effective and efficient communication platforms. The contributing factors include the availability of internet and intranet facilities with the required bandwidth, cloud-based applications, portability of services via online interfaces for performing administrative tasks and public services, and the inclination of the public in accepting these services. The way civil servants worked during the pandemic was unprecedented, neglecting most of the well-planned studies and theories, shifting them into oblivion. The episodes they went through during the pandemic forms a new plethora of performances within a vicinity that is currently being studied extensively and globally by various scholars and professionals alike. However, the pandemic is not expected to prevail. Once it is over, the organisations will take the natural tendency of reverting to regular methods of work, enlivening the organisational culture and natural job demands. At the workplace, regular human interactions, face to face meetings, and communication protocols will soon commence, with decision making processes accomplished through various methods of interactions between individuals in the workforce. The findings of this study will apply to such conditions, as an emotionally intelligent and highly skilled workforce will need to be highly productive in a renewed competitive environment and work culture. The mindset of the civil servants is expected to be undeterred once they are back to the old ways of working, proving the study results to be applicable and valid post-pandemic in the regular work environment. Malaysia’s experience during this pandemic is not in isolation from other countries, allowing for the global applicability of these findings.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This research has had some limitations. Understanding the limitations and their possible effect on the results and the conclusion is vital to understanding the problem investigated. Firstly, this research was conducted in the public administration of five ministries. Hence, the sample did not include public administrators from other ministries. Being a cross-sectional research, it allowed the study to be concluded in a shorter timeframe. On the contrary, a longitudinal study demanding a longer timeframe may improve or offer different results, providing an opportunity for the observation of individuals at work. Secondly, the name of the five ministries and the breakdown of the respondents from the respective ministries were not available to the researchers due to restrictions and anonymity. Thirdly, as the data was collected through a questionnaire survey, respondents may have been cautious or might have acted conservatively when providing their answers. Finally, this research accounts for certain dimensions of EI based on the definition provided by Goleman et al. (2002), and did not include dimensions of EI highlighted by Bar-On (2012), Petrides and Furnham (2000, 2006), and other scholars. However, the ability test is an appropriate tool for research work related to attitudes such as job satisfaction and work performance (O’Boyle et al. 2010; Miao et al. 2017), which can be a prospective area for future research. The results of the study may be fortified should differing dimensions of EI be used.

This study recommends that future research be performed on other government departments outside of Putrajaya, the administrative capital of Malaysia, and within the state governments, to establish the contribution of EI on a broader scale. The scope of this research can be extended beyond ADOs, to the officers and managers in the public administration. The EI of different grades with different job scopes may serve to provide a better check and balance on the findings. Expanding the dimensions of the demographic data (i.e., collecting information about the respondents’ ministry/department) will allow for a deeper analysis of the results that could produce different perspectives on the discussion. Future research may explore various dimensions of EI to ascertain the success of various alternative scopes of EI at the workplace. Future research may also be conducted on different industries, targeting organisations in the private sector, to establish the direct effect of EI on OP. Another suggestion is to conduct a qualitative research through interviews in order to further attain additional information that may produce improvised results. In order to achieve this, the questionnaire can be amended to suit the organisational environment, the participants’ levels, and other relevant scenarios. On a greater scale, an inclusive study can be undertaken to include the staff of various governmental organisations by extending the study to the representatives of other countries through the respective embassies, consulates, and commissions. This will present a great opportunity to investigate the global perspectives of governments and their performances.

Emotionally intelligent public administrators, who are well versed in the digitalisation of processes and policies, are naturally aware of their emotions and the emotions of others, avoiding a robotic environment. This creates an element of motivation and determination amongst the public administrators at work. The digitalisation of the organisation is envisaged to have an impact in the way data is collected, stored, and analysed. From the EI perspectives of the public administrators, or the employees of organisations at large, this presents itself as another broad area for future research in the promising digital age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.S. and K.S.; methodology, S.S.; validation, S.S. and K.S., formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and K.S.; supervision, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the survey is not linked to any risks to participants, did not entail a collection of sensitive data, and did not involve vulnerable populations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed in the current study are not publicly available due to further, ongoing research projects but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the key representatives and the respondents of the study, consisting of ADOs based in the Administrative Capital of Malaysia, for their time and willingness to participate in the survey and complete the questionnaires.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 lists the questionnaire items that were mapped to the EI variables and the respective indicators.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items addressing the EI variables and indicators.

Table A1.

Questionnaire items addressing the EI variables and indicators.

| Variables | Indicators | Questionnaire Items |

|---|---|---|

| SELF AWARENESS | ESA1 | I am aware of my state of mood at work. |

| ESA2 | I respond positively to events that frustrate me. | |

| ESA3 | I take criticism from colleagues personally. | |

| ESA4 | I am aware of how my feelings influence the decisions I make at work. | |

| ESA5 | I find it difficult to recognize my feelings on issues at work. | |

| ESA6 | I am aware of my friends’ emotions from their behaviour. | |

| ESA7 | I effectively deal with things that annoy me at work. | |

| SELF MANAGEMENT | AO1 | I respond appropriately to colleagues who frustrate me at work. |

| AO2 | I fail to handle stressful situations at work effectively. | |

| AO3 | I initiate actions to improve my own performance. | |

| AO4 | I seek to improve my own self by setting measurable and challenging goals. | |

| AO5 | I strive to improve my own performance. | |

| AO6 | I do not try to improve. | |

| ESC1 | I do not attempt to improve my own performance. | |

| ESC2 | I seek to do things in a better way. | |

| SOCIAL AWARENESS | EMP1 | I demonstrate to others that I have considered their feelings in decisions I make at work. |

| EMP2 | I am sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others. | |

| EMP3 | I have good understanding of the emotions of the people around me. | |

| EMP4 | I am a good observer of others’ emotions. | |

| EMP5 | I respond effectively to others’ feelings. | |

| EMP6 | I accurately view situations from other’s perspectives. | |

| RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT | INFL1 | I help create a positive work environment. |

| INFL2 | I help others resolve workplace conflicts. | |

| INFL3 | I provide useful support to others. | |

| INFL4 | I help others respond effectively to stressful situations. | |

| INFL5 | I positively influence the way others feel. |

Table A2 lists the questionnaire items that were mapped to the OP variables and the respective indicators.

Table A2.

Questionnaire items addressing the OP variables and indicators.

Table A2.

Questionnaire items addressing the OP variables and indicators.

| Variables | Indicators | Questionnaire Items |

|---|---|---|

| LEARNING AND GROWTH | LG1 | Leadership defines the organisation’s vision and values. |

| LG2 | Leadership establishes organisation’s vision and values. | |

| LG3 | Leadership encourages employees to attend training. | |

| LG4 | Leadership ensures succession planning. | |

| LG5 | Leadership participates in the development of future leaders. | |

| INTERNAL PROCESS | IP1 | Leadership deploys the organisation’s vision and values through its leadership system, to the workforce. |

| IP2 | Leadership deploys the organisation’s vision & values via its leadership system, to suppliers & partners. | |

| IP3 | Leadership deploys the organisation’s vision and values through its leadership system, to customers. | |

| IP4 | Leadership motivates the entire workforce. | |

| IP5 | Leadership does not communicate with the entire workforce. | |

| FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE | FP1 | Leadership does not take an active role in reward programs to reinforce high performance. |

| FP2 | Leadership takes an active role in recognition programs to reinforce high performance. | |

| FP3 | Leadership does not create a focus on action to accomplish organisation objectives. | |

| FP4 | Leadership creates a focus on action to improve performance. | |

| STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVE | SH1 | Leadership creates a focus on action to attain its vision. |

| SH2 | Leadership creates an environment for the accomplishment of the company’s mission. | |

| SH3 | Leadership does not create an environment for strategic objectives. | |

| SH4 | Leadership includes a focus on balancing value for customers in their performance expectations. | |

| SH5 | Leadership does not include a focus on balancing value for stakeholders in their performance expectations. | |

| SH6 | Leadership creates an environment for performance improvement. |

References

- Adeoye, Hammed, and Victor Torubelli. 2011. Emotional intelligence and human relationship management as predictors of organizational commitment. IFE PsycholoiA: An International Journal 19: 212–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, Arawati, Sunita Barker, and Jay Kandampully. 2007. An Exploratory Study of Service Quality in the Malaysian Public Service Sector. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 24: 177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, Nasser Saad, Manzil M. Sulphey, Kevin Delany, and Anass Hamad Elneel Adow. 2021. A Conceptual Examination about the Correlates of Psychological Capital (PsyCap) among the Saudi Arabian Workforce. Social Sciences 10: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, Barbara A., Barbara R. Dastoor, and Josephine Sosa-Fey. 2010. Emotional intelligence and leadership: A study of human resource managers. International Journal of Business and Public Administration 7: 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidis, John, and Nabil A. Ibrahim. 2011. The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on the Ethical Judgment of Managers. Journal of Business Ethics 99: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfara, Christina, and Irene Samanta. 2016. The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Improving Team-Working: The Case of Public Sector (National Centre for Public Administration and Local Government—N.C.P.A.L.G. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 230: 167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, Bruce J., Fred O. Walumbwa, and Todd J. Weber. 2009. Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 421–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baczyńska, Anna, and George C. Thornton. 2017. Relationships of Analytical, Practical, and Emotional Intelligence with Behavioral Dimensions of Performance of Top Managers. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 25: 171–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Reuven. 2012. Emotional Quotient-Inventory. New York: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfanti, Charmaine. 2017. Emotional Capacity in the Public Sector—An Australian Review. International Journal of Public Sector Management 30: 429–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, Ira. 2008. Selecting employees based on emotional intelligence competencies: Reap the rewards and minimize the risk. Employee Relations Law Journal 34: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Richard E. 2001. How and Why Individuals Are Able to Develop Emotional Intelligence. The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, Measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in Individuals, Groups, and Organizations. Edited by Cary Cherniss and Daniel Goleman. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Richard E., Darren Good, and Raymond Massa. 2012. Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Intelligence and Personality as Predictors of Sales Leadership Performance. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 19: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, Nikos, and Sanjay Kumar Singh. 2017. The Relationship of Emotional Intelligence with Task and Contextual Performance: More Than It Meets the Linear Eye. Personality and Individual Differences 116: 206–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradberry, Travis, and Jean Greaves. 2012. Emotional Intelligence Appraisal—Multi-Rater Edition. PsycTESTS Dataset, September 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcea, Ştefan Gabriel, and Oana Matilda Sabie. 2020. Is Emotional Intelligence a Determinant Factor for Leader’s Skills Development? Essential Literature Perspectives. Management and Economics Review 5: 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, Cynthia Rodriguez, and Doreen Sams. 2009. The Importance of an Internal Marketing Orientation in Social Services. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 14: 285–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Abraham. 2003. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Work Attitudes, Behavior and Outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology 18: 788–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, Anthony Patrick, Leila J. Gainer, and Ann S. Meltzer. 1988. Workplace Basics: The Skills Employers Want; Alexandria: American Society for Training and Development, Washington, DC: U. S. Bureau of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

- Cavazotte, Flavia, Valter Moreno, and Mateus Hickmann. 2012. Effects of Leader Intelligence, Personality and Emotional Intelligence on Transformational Leadership and Managerial Performance. The Leadership Quarterly 23: 443–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniss, Cary. 2001. Emotional Intelligence: What It Is and Why It Matters. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 15. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Nicholas. 2010. Emotional Intelligence Abilities and Their Relationships with Team Processes. Team Performance Management: An International Journal 16: 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hoboken: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Molina, Deybbi, Antonia Mercedes García-Cabrera, and Ma de la Cruz Déniz-Déniz. 2019. Emotional intelligence of the HR decision-maker and high-performance HR practices in SMEs. European Journal of Management and Business Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, Satish P., Jacob Joseph, and Xiaonan Shu. 2005. The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Counterproductive Behaviour in China. Management Research News 28: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druskat, Vanessa Urch, and Steven B. Wolff. 2001. Group-Level Emotional Intelligence. Research Companion to Emotion in Organizations, 441–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, Toby Marshall. 2008. The Relevance of Organizational Subculture for Motivation to Transfer Learning. Human Resource Development Quarterly 19: 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerling, Robert J., and Richard E. Boyatzis. 2012. Emotional and Social Intelligence Competencies: Cross Cultural Implications. Edited by Robert Emmerling. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 19: 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Axel Buchner, and Albert-Georg Lang. 2009. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behavior Research Methods 41: 1149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, Claes, and Fred L. Bookstein. 1982. Two Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS Applied to consumer Exit-Voice Theory. Journal of Marketing Research 19: 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and Jaesung Cha. 1994. Partial least squares: Advanced methods of marketing research. Advanced Methods of Marketing Research 407: 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Freshman, Brenda, and Louis Rubino. 2004. Emotional Intelligence Skills for Maintaining Social Networks in Healthcare Organizations. Hospital Topics 82: 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, David, Detmar Straub, and Marie-Claude Boudreau. 2000. Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Gabriele, Luigi Isaia Lecca, Federico Alessio, Georgia Libera Finstad, Giorgia Bondanini, Lucrezia Ginevra Lulli, Giulio Arcangeli, and Nicola Mucci. 2020. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, Daniel, and Richard Boyatzis. 2008. Social intelligence and the biology of leadership. Harvard Business Review 86: 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, Daniel, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee. 2002. The Emotional Reality of Teams. Journal of Organizational Excellence 21: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1995. Emotional Intelligence: A New Vision for Educators. PsycEXTRA Dataset. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunu, Umar, and Rasheed Oladepo. 2014. Impact of emotional intelligence on employees’ performance and organizational commitment: A case study of Dangote Flour Mills workers. University of Mauritius Research Journal 20: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, Mary E., and Hyun Jung Lee. 2015. How Emotional Intelligence Mediates Emotional Labor in Public Service Jobs. Review of Public Personnel Administration 35: 261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., Marko Sarstedt, Christian M. Ringle, and Siegfried P. Gudergan. 2017. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, Peter D., and Marcus Credé. 2010. Emotional Intelligence and Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 17: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, James D., and Arnold C. Bacigalupo. 2011. Enhancing Decisions and Decision-making Processes through the Application of Emotional Intelligence Skills. Edited by Erwin Rausch. Management Decision 49: 710–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Young Hee, Peter T. van den Berg, and Celeste P. M. Wilderom. 2011. Transformational Leadership as a Mediator Between Emotional Intelligence and Team Outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly 22: 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain-Rahim, Saddam, and Muhammad Imran Malik. 2010. Emotional Intelligence & Organizational Performance: (A Case Study of Banking Sector in Pakistan). International Journal of Business and Management 5: 191–97, (to change this to Hussain in the incite text). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Azman, Yeo Suh-Suh, Mohd Na’eim Ajis, and Noor Faizzah Dollah. 2009. Relationship between Occupational Stress, Emotional Intelligence and Job Performance: An Empirical Study in Malaysia. Theoretical & Applied Economics 16: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Peter J., and Ashlea C. Troth. 2004. Managing Emotions During Team Problem Solving: Emotional Intelligence and Conflict Resolution. Human Performance 17: 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2005. The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 83: 172. [Google Scholar]

- Kernbach, Sally, and Nicola S. Schutte. 2005. The Impact of Service Provider Emotional Intelligence on Customer Satisfaction. Journal of Services Marketing 19: 438–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Robert, John Garvin, Norma Heaton, and Emily Boyle. 2006. Emotional Intelligence and Leadership Effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 27: 265–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Tae-Yeol, Daniel M. Cable, Sang-Pyo Kim, and Jie Wang. 2009. Emotional Competence and Work Performance: The Mediating Effect of Proactivity and the Moderating Effect of Job Autonomy. Journal of Organizational Behavior 30: 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Jean-Lee, Siew, and Kelvin Yu. 2004. Corporate Culture and Organizational Performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology 19: 340–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Ming-Fong, and Gwo-Guang Lee. 2007. Relationships of Organizational Culture Toward Knowledge Activities. Business Process Management Journal 13: 306–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Kenneth S., Chi-Sum Wong, and Lynda J. Song. 2004. The Construct and Criterion Validity of Emotional Intelligence and Its Potential Utility for Management Studies. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 483–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Hyun Jung. 2018. How Emotional Intelligence Relates to Job Satisfaction and Burnout in Public Service Jobs. International Review of Administrative Sciences 84: 729–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, Peter, and John Crawford. 2001. Antecedents of Organizational Commitment and the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology 16: 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Paulo N., Daisy Grewal, Jessica Kadis, Michelle Gall, and Peter Salovey. 2006. Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work. Psicothema 18: 132–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Zafra, Esther, Rocio Garcia-Retamero, and M. Pilar Berrios Martos. 2012. The relationship between transformational leadership and emotional intelligence from a gendered approach. The Psychological Record 62: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]