Authentic Talent Development in Women Leaders Who Opted Out: Discovering Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Kaleidoscope Career Model

2.1. Authenticity

2.2. Balance

2.3. Challenge

3. Gender Based Alpha and Beta KCM Career Patterns

4. The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership

4.1. Model the Way

4.2. Inspire a Shared Vision

4.3. Challenge the Process

4.4. Enable Others to Act

4.5. Encourage the Heart

5. Gender and Leadership Practices

5.1. Research Questions

5.2. Sub-Questions Concerning the Opting Out and Opting in Processes Included

6. Method

6.1. Study 1 Research Sample and Survey Administration

6.1.1. Study 1 Measures

6.1.2. Study 1 Findings

6.1.3. Study 1: Findings

6.1.4. Summary of Results, Study 1

6.2. Study 2: Qualitative Approach to Women’s Reasons for Opting Out and Re-Entry Experiences

6.2.1. Study 2 Research Sample and Interview Administration

- Mothers who after having kids exited the workplace.

- “High Achieving Professional Women” is based on Pamela Stone’s research and includes women who are highly educated, previously worked as professionals or managers, and able to be financially supported at home (Stone 2007).

- Presently worked a minimum of 24 h each week in a U.S. organization.

- Member checking opt-in to ensure trustworthiness (Lincoln and Guba 1986).

- Aged between 37–45.

6.2.2. Study 2 Interview Process and Data Collection

6.2.3. Study 2 Qualitative Data Analysis

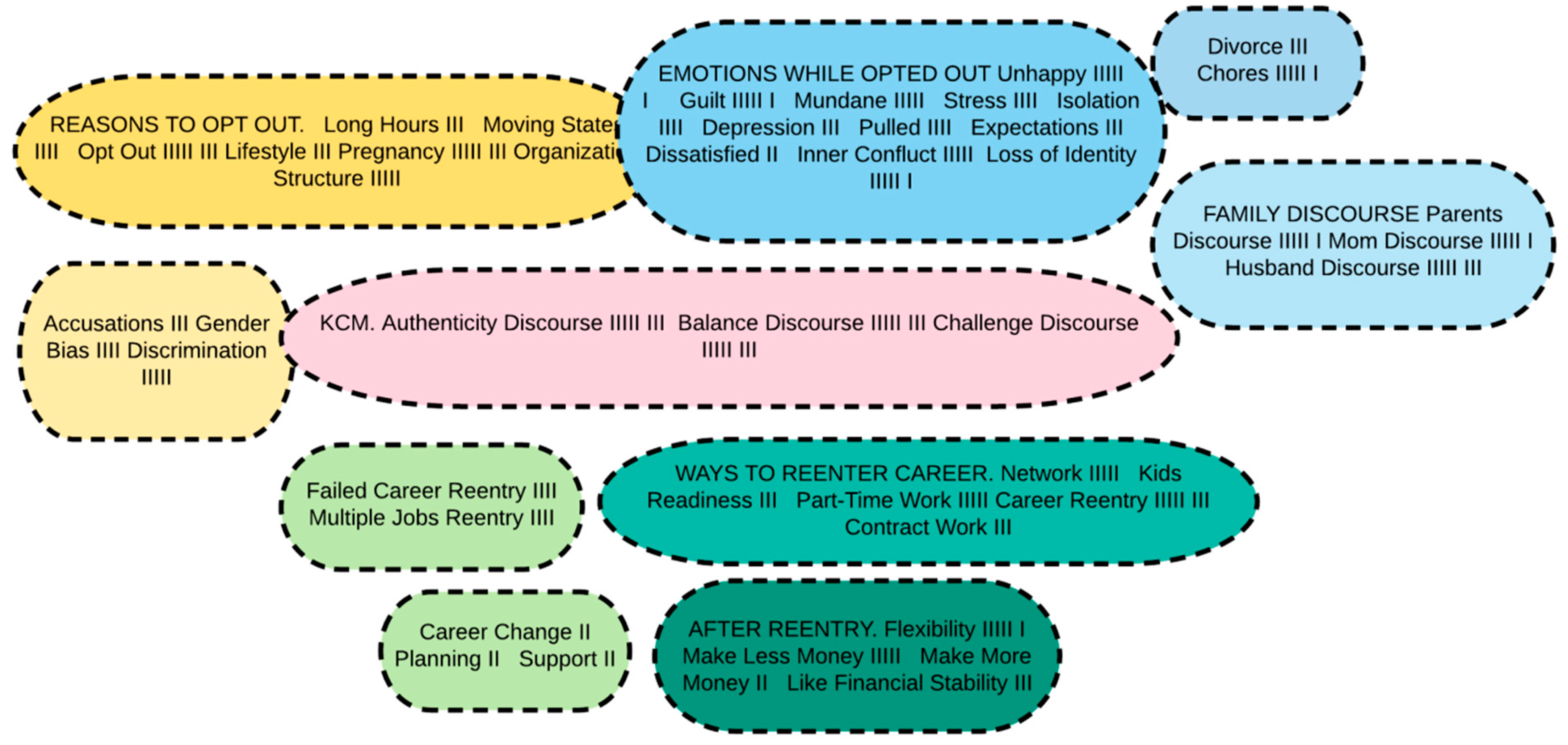

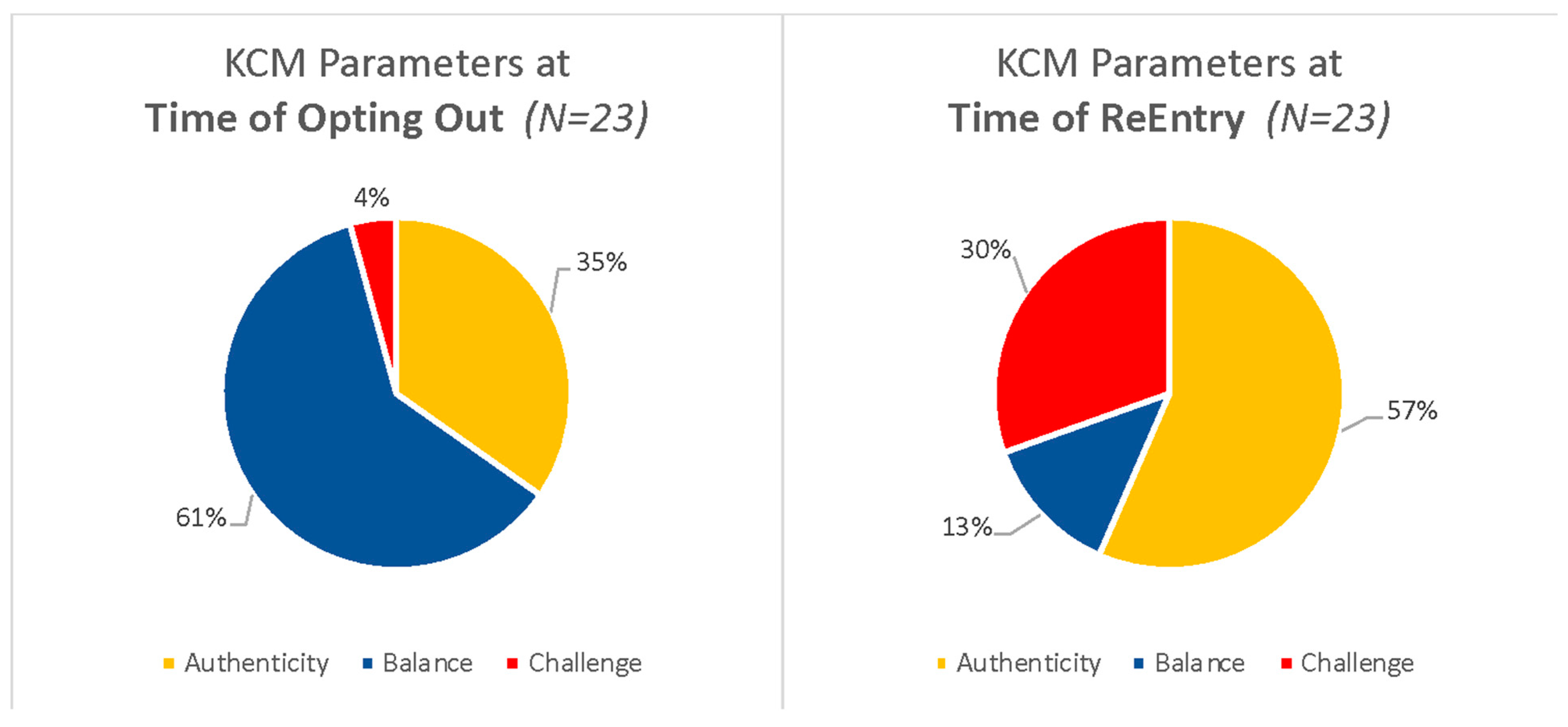

6.2.4. Study 2 Findings

Authenticity as a Factor in Opting Out (N = 8)

“My father died. This changed my core and forced me to look at what was most important in my life. Suddenly, achieving that promotion did not seem so important”.

“I had a miscarriage. While my doctor said it wasn’t related to my high stress at work, I disagree. I needed to relook at my life and figure out what was my priority”.

“I feel torn. If I have passion at work and a meaningful role, I am home less. To be authentic, finding the right workplace is key and there are certain industries I now stay away from”.

Balance as a Factor in Opting Out (N = 14)

“Everyone said I could do it, working full time and being a mom. It hit home when a co-worker said ‘My son doesn’t recognize me and cries…’ And when thinking about it, I realized my boss had three nannies. Was this how I wanted to live my life? … I needed to take a pause and reboot”.

“I went back to work after I had my first child. I thought I could do it all. The stress and demands at work were too much for me when I had a little baby at home who needed me. I decided to quit”.

“My husband worked all the time. While I was planning on going back to work, when my maternity leave was up, I just couldn’t go back. I knew that being the primarily parent would fall mostly on me, even if I was working full-time. I would always carry the mental load of parenting. And things like housework were also my responsibility. I called my old boss and said I was not returning”.

Challenge as a Factor in Opting Out (N = 1)

“I couldn’t keep up with the demands of my job anymore. The challenges that were required of me at work and the demands of my life at home caused me to be stretched too thin”.

“When I returned from maternity, I moved to a less demanding job that required less hours. I was so bored and unstimulated. I made less money. After a while, I asked, “Why am I doing this? I missed the challenge of my old position but knew I could never go back”.

Authenticity as a Factor at Time of Re-Entry (N = 9)

“I am absolutely living an authentic life. I feel fulfilled now that I’ve created my own business. I don’t have to worry about corporate stuff anymore—biting my tongue, eye rolling, watching my male co-workers get promoted more than me. My job enables my lifestyle”.

“I chose a new job, a new career. Now my profession fits with my life. I can be there for my kids and also earn money for myself. Sure, I miss aspects of my old job, especially pay and sometimes I’m bored, but I’m doing it my way and my family thanks me”.

“When I went back to work, it didn’t feel like I was doing authentic work. Finding a role that fits will make me feel more authentic”.

“After reentering my career, I feel authentic, but I would like to be even more authentic to myself, but it’s hard”.

Balance as a Factor at Time of Re-Entry (N = 3)

“Balance is attainable, but I can’t hold onto it for very long. This morning I was up at 4:30 a.m. with my son. Balance is a constant struggle and juggle. Sometimes balance is present, sometimes it is not. If someone is sick, things fall apart”.

“When I went back to work, I couldn’t get everything done. Everything started slipping. I forgot stuff at my daughter’s school, I forgot doctor’s appointments, I didn’t have time for friends”.

“Even now that I entered the workforce, my balance is falling apart. I’m bitter at my husband because he doesn’t help out. He doesn’t feel value at home, so he immerses himself at work”.

“And I still did all the housework and chores. We had issues of labor. I was the primary breadwinner and my husband felt emasculated. We have since divorced”.

Challenge as a Factor at Time of Re-Entry (N = 7)

“Sometimes I don’t feel utilized at work. I sacrifice challenge for balance”.

“I have less drive now. I am at the right level of challenge for my life right now. I will not advance anytime soon but that is okay. I enjoy being home with my family”.

“I am not as focused and invested as I used to be. It is hard to compartmentalize work and family. My job does not showcase my strengths but now I have independence and flexibility which is more important”.

6.2.5. Study 2 Summary of Findings

7. Discussion

7.1. Implications for Authentic Talent Development

- Develop new tailored career tracks that emphasize the needs for authenticity, balance and challenge,

- Celebrate the “new normal” post COVID-19 that contemporary career paths will allow for mobile work and telecommuting options that do not discourage advancement,

- Administer flexible work schedules, such as reduced hours, job sharing options, alternative work arrangements,

- Recognize that those who opt out for a temporary career interruption for family reasons can return to their former jobs with enhanced skills, ready for future leadership development,

- Create mentoring and coaching circles so that managers can develop a variety of employees at different stages of their careers,

- Champion high achieving women who have opted out for balance reasons for upper-level positions when they return,

- Hardwire the infrastructure for contemporary career paths based on merit and performance, including examining job descriptions and organizational charts to ensure equal opportunities exist,

- Revisit the mission, vision, and values of the organization to ensure authentic talent development programs are part of the company’s strategic direction.

7.2. Study 1 and 2 Limitations and Future Research

7.3. Recommendations for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. KCSI Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge Scales

- Authenticity

- I hope to find a greater purpose to my life that suits who I am.

- I hunger for greater spiritual growth in my life.

- I have discovered that crises in life offer perspectives in ways that daily living does not.

- If I could follow my dream right now, I would.

- I want to have an impact and leave my signature on what I accomplish in life.

- Balance

- If necessary, I’d give up my work to settle problematic family issues or concerns.

- I constantly arrange my work around my family needs.

- My work is meaningless if I can’t take the time to be with my family.

- Achieving balance between work and family is life’s holy grail.

- Nothing matters more to me right now than balancing work with my family responsibilities.

- Challenge

- I continually look for new challenges in everything I do.

- I view setbacks not as “problems” to be overcome but as “challenges” that require solutions.

- Added work responsibilities don’t worry me.

- Most people would describe me as being very goal-directed.

- I thrive on work challenges and turn work problems into opportunities for change.

- Response Scale

- 1 = This does not describe me at all

- 2 = This describes me somewhat

- 3 = This describes me often

- 4 = This describes me considerably

- 5 = This describes me very well

Appendix B

| I praise my workers when they accomplish important milestones. |

| I follow through on the promises and commitments that I make to my employees. |

| I find ways to reward my workers for a job well done. |

| I make certain that the people I work with adhere to the principles and standards that we have agreed on. |

| I develop cooperative relationships among the people I work with. |

| I provide frequent feedback on how people are doing. |

| I inspire others with optimistic plans for the future. |

| I encourage the development of others through stretch goals. |

| I offer to coach others to aid their skill development. |

| I listen carefully to the concerns of others. |

| I demonstrate conviction in my values to “walk the talk”. |

| I am enthusiastic about our mission for the company. |

| I talk optimistically about the future of the firm. |

| I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure. |

| I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities. |

References

- Ackermans, Jos, Scott E. Siebert, and Stefan T. Moi. 2018. Tales of the unexpected: Integrating career shocks in contemporary career literature. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 44: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Todd C., and Marybelle C. Keim. 2000. Leader practices and effectiveness among Greek student leaders. College Student Journal 34: 259–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, Maryam, and Sara Chaudry. 2020. Women and burnout in the context of a pandemic. Gender, Work and Organizations 28: 826–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artabane, Melissa, Julie Coffman, and Darci Darnell. 2017. Charting the Course: Getting Women to the Top. Bain and Co. Special Report. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/charting-the-course-women-on-the-top/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- August, Rachel. 2011. Women’s later life career development: Looking through the lens of the Kaleidoscope career model. Journal of Career Development 38: 208–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Karen W. 2004. Conducting longitudinal studies. New Directions for Future Research 121: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Anthony S., Ann Marie Ryan, Anna L. Imus, and Frederick P. Morgeson. 2007. Temporary worker, permanent loser?: A model of the stigmatization of temporary workers. Journal of Management 33: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, Jeanne M., and Linda K. Stroh. 2003. Working 61 plus hours a week: Why do managers do it? Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, Elizabeth F. 2007. Opting out and opting in: Understanding the complexities of women’s career transitions. Career Development International 12: 218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, Sally A. 1998. Gender differences in transformational leadership: An examination of superior leader and subordinate perspectives. Sex Roles 39: 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnaghan, Seth, and Brad N. Greenwood. 2018. Managers political beliefs and gender inequality among subordinates: Does his ideology matter more than hers? Administrative Science Quarterly 63: 287–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Curtis K., and Michel Anteby. 2016. Task segregation as a mechanism for within-job inequality: Women and men of the transportation security administration. Administrative Science Quarterly 61: 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.M., and P.S. Reed. 2007. Are We Losing the Best and the Brightest? Highly Achieved Women Leaving the Traditional Workforce. Available online: https://www.doleta.gov/reports/pdf/arewelosingthebest.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2016).

- Clarke, Adele E. 2005. 2005 Situational Analysis. Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clisbee, Mary A. 2004. Leadership Style: Do Male and Female School Superintendents Lead Differently? Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power and Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Lisa E., and Joseph P. Broschak. 2013. Whose jobs are these? The impact of the proportion of female managers on the number of new management jobs filled by women versus men. Administrative Science Quarterly 58: 509–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Couper, Mick P. 2000. Web surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opinion Quarterly 64: 464–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronbach, Lee J. 1990. Essentials of Psychological Testing, 5th ed. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, Ans, and Beatrice IJM Van der Heijden, eds. 2009. Career mobility at the intersection between agent and structurche: A conceptual model. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Debebe, Gelaye. 2017. Authentic leadership and talent development: Fulfilling Individual Potential in Sociocultural Context. Advances in Developing Human Resources 19: 420–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, Thomas J., and Vineeta Vijayaraghavan. 2003. Let’s hear it for B players. Harvard Business Review 81: 96–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Desai, Sreedhari D., Dolly Cheugh, and Arthur P. Brief. 2014. The implications of marriage structure on men’s workplace attitudes, behaviors and beliefs towards women. Administrative Science Quarterly 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbert, Marion Lundy. 1982. Ethnographic Research: Theory and Application for Modern Schools and Societies. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Linda Carli. 2007. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth about How Women Leaders Become Leaders. Boston: Harvard University Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Steven J. Karau. 2002. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Bulletin 109: 573–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, Alice H., M. C. Johannesen-Schmidt, and M. L. van Engen. 2003. Transactional, transformational and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin 129: 569–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagenson-Eland, Ellen A., and S. Gayle Baugh. 2001. Personality predictors of protégé mentoring history. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31: 2502–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Margie L., Jeffrey C. Marshall, Mary Lisa Pories, and Morgan Daughety. 2014. Factors affecting undergraduate leadership behaviors. Journal of Leadership Education 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Bill. 2003. Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, Vijai N., and Tirumala Santra. 2009. Effects of job experience, career stage, and hierarchy on leadership style. Singapore Management Review 32: 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Gerard A. Callanan, and Veronica M. Godshalk. 2018. Career Management for Life. London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M. E. 2001. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues 57: 657–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, Madeline E., Aaron S. Wallen, Daniella Fuchs, and Melinda M. Tamkins. 2004. Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender typed tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 416–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, and Carolyn B. Luce. 2005. Off-ramps and on-ramps: Keeping talented women on the road to success. Harvard Business Review 83: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Laura Sherbin, and Diana Forster. 2010. Off-Ramps and On-Ramps Revisited. Available online: https://hbr.org (accessed on 11 May 2017).

- Hirschi, Andreas. 2010. The role of chance events in the school-to-work transition: The influence of demographic, personality and career development variables. Journal of Vocational Behavior 77: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Andreas, and Domingo Valero. 2017. Chance events and career decidedness: Latent profiles in relation to work motivation. The Career Development Quarterly 65: 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie. 2003. The Second Shift. New York: Avon Books. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, Herminia. 2003. Working Identity: Unconventional Strategies for Reinventing Your Career. Boston: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A. 2014. By Whom and When Is Women’s Expertise Recognized? The Interactive Effects of Gender and Education in Science and Engineering Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly 59: 202–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judiesch, Michael K., and Karen S. Lyness. 1999. Left behind? The impact of leaves of absence on managers’ career success. Academy of Management Journal 42: 641–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeyer, Catherine. 1998. Determinants of managerial career success: Evidence and explanation of male/female differences. Journal of Management 24: 673–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeyer, Catherine. 2002. Gender differences in managerial careers: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Journal of Business Ethics 37: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Anne. M., Alice H. Eagly, Abigail A. Mitchell, and Tiina Ristikari. 2011. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin 137: 616–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ellen E., Rong Su, and Lusi Wu. 2017. Opted out or pushed out? Integrating perspectives on women’s career equality for gender inclusion interventions. Journal of Management 43: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, Jim, and Barry Posner. 2002. The Leadership Practices Inventory: Theory and Evidence Behind the Five Practices of Exemplary Leaders. Available online: http://www.leadershipchallenge.com (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Kouzes, Jim, and Barry Posner. 2007. The Leadership Challenge, 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes, Jim, and Barry Posner. 2011. The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Daniel J. 1978. The Seasons of a Man’s Life. New York: Alfred Knopf, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1986. But is it rigorous: Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation 6: 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, Charlotte. 1993. Life Stories. The Creation of Coherence. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, Fred, and Bruce Avolio. 2003. Authentic leadership development. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline. Edited by K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton and R. E. Quinn. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lyness, Karen S., and Donna E. Thompson. 2000. Climbing the corporate ladder: Do female and male executives follow the same route? Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainiero, Lisa A., and Donald E. Gibson. 2017. The Kaleidoscope career model revisited: How men and women diverge on authenticity, balance, and challenge. Journal of Career Development, 451–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainiero, Lisa A., and Sherry E. Sullivan. 2005. Kaleidoscope careers: An alternate explanation for the ‘opt-out’ revolution. Academy of Management Journal 19: 106–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainiero, Lisa A, and Sherry E. Sullivan. 2006. The Opt-Out Revolt: Why People Are Leaving Companies to Create Kaleidoscope Careers. Mountain View: Davis-Black. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2006. Designing Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McEldowney, Rene P, Paula Bobrowski, and Anna Gramberg. 2009. Factors affecting the next generation of women leaders: Mapping the challenges, antecedents, and consequences of effective leadership. Journal of Leadership Studies 3: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, George A., Nancy L. Leech, Gene W. Gloeckner, and Karen C. Barrett. 2013. IBM SPSS for Introductory Statistics, 5th ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Deborah A., Margaret M. Hopkins, and Diana Bilmoria. 2008. Women’s careers at the start of the 21st century: Patterns and paradoxes. Journal of Business Ethics 80: 727–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, Paul. 1996. Broken Ladders. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padavic, Irene, Robin M. Ely, and Erin M. Reid. 2020. Explaining the persistence of gender inequality: The work-family narrative as a social defense against the 24/7 work culture. Administrative Science Quarterly 65: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett, Marjorie A., Nancy R. Lackey, and John J. Sullivan. 2003. Making Sense of Factor Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Philip M. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method bias in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommendations for social science researchers. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, Barry Z. 2004. A leadership development instrument for students updated. College Student Development 45: 443–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Gary N., and D. Anthony Butterfield. 2003. Gender, gender identity, and aspirations to top management. Women in Management Review 18: 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragins, Belle R., Bickley Townsend, and Mary Mattis. 1998. Gender gap in the executive suite: CEOS and female executives report on breaking the glass ceiling. Academy of Management Perspectives 12: 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reskin, Barbara. 2012. The race discrimination system. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reskin, Barbara, and Denise Bielby. 2005. A sociological perspective on gender and career outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Ken. 2009. The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Ken. 2013. Finding Your Element: How to Discover Your Talents and Passions and Transform Your Life. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, Kathryn, V. J. McClendon, Anthony Thomas, Raegan Tuff, Gwendolyn Williams, and Michael F. Healy. 2008. Developing reflective interviewers and reflective researchers. Journal of Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 9: 231–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, Marian, and Patricia Ohlott. 2002. Standing at the Crossroads: Next Steps for High-Achieving Women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, Laurie, and Julie E. Phelan. 2008. Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, Virginia E. 1973. The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology 57: 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, Virginia E. 2001. A global look at psychological barriers to women’s progress in management. Journal of Social Issues 57: 675–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneer, Joy A., and Frieda Reitman. 1995. The impact of gender as managerial careers unfold. Journal of Vocational Behavior 47: 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneer, Joy A., and Frieda Reitman. 1997. The interrupted managerial career path: A longitudinal study of MBAs. Journal of Vocational Behavior 51: 411–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Felice. 1989. Management women and the new facts of life. Harvard Business Review 67: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Mary, Cynthia Ingols, and Stacy Blake-Beard. 2008. Confronting career double binds: Implications for women, organizations, and career practitioners. Journal of Career Development 34: 309–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrowe, Raymond T. 2005. Authentic leadership and the narrative self. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 419–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Pamela. 2007. Opting Out? Why Women Really Quit Careers and Head Home. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Pamela, and Lisa A. Hernandez. 2012. Toward a better understanding of professional women’s decision to head home. In Women Who Opt Out: The Debate over Working Mothers and Work-family Balance. Edited by B. Jones. New York: NYU Press, pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Sherry E., and Lisa A. Mainiero. 2007a. The changing nature of gender roles, alpha/beta careers and work-life issues: Theory-driven implications for human resource management. Career Development International 12: 238–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Sherry E., Monica L. Forret, Shawn M. Carraher, and Lisa A. Mainiero. 2009. Using the kaleidoscope career model to examine generational differences in work attitudes. Career Development International 14: 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Sherry E., and Lisa A. Mainiero. 2007b. Kaleidoscope careers: Benchmarking ideas for fostering family-friendly workplaces. Organizational Dynamics 36: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E. 1957. Psychology of Careers. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P. 2001. Do traits and informal social processes predict advancing in management? Academy of Management Journal 44: 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Karen S., and Donna E. Lyness. 1997. Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. Journal of Applied Psychology 82: 359–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA Today. 2007. Nancy Pelosi Speaks about Being a Mom. May 10. Available online: https://www.speaker.gov/newsroom/usa-today-nancy-pelosi-speaks-mom (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Valcour, Monique, Lotte Bailyn, and Maria A. Quidada. 2007. Customized careers. In Handbook of Careers. Edited by Hugh Gunz and Maury Peiprl. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Weyer, B. 2007. Twenty years later: Explaining the persistence of the glass ceiling for women leaders. Women in Management Review 22: 482–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Birgit. 1995. The career development of successful women. Women in Management Review 10: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Kevin B. 2006. Researching internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | % of Sample | Characteristics | % of Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 52% | Industry | |

| Male | 48% | Manufacturing | 14% |

| Caucasian | 84% | Financial services | 12% |

| Black | 9% | Retail | 10% |

| Asian | 3% | Education | 9% |

| Native American | 1% | Health care | 8% |

| Other | 3% | Government | 6% |

| 3% | Hospitality & food services | 5% | |

| <High school diploma | 3% | Transportation | 4% |

| High school diploma | 19% | ||

| Some college | 29% | Communication | 3% |

| 2 year degree | 14% | Other | 28% |

| 4 year degree | 20% | Has children | 58% |

| Some post graduate education | 4% | No children | 42% |

| Married | 47% | ||

| Single | 25% | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 20% | ||

| Living with a partner | 8% |

| Rotated Component Matrix a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||||

| Encourage the Heart | Enable Others to Act | Model the Way | Inspire a Shared Vision | Challenge the Process | |

| I praise my workers when they accomplish important milestones. | 0.799 | ||||

| I follow through on the promises and commitments that I make to my employees. | 0.768 | ||||

| I find ways to reward my workers for a job well done. | 0.767 | ||||

| I make certain that the people I work with adhere to the principles and standards that we have agreed on. | 0.747 | ||||

| I develop cooperative relationships among the people I work with. | 0.726 | ||||

| I provide frequent feedback on how people are doing. | 0.747 | ||||

| I inspire others with optimistic plans for the future. | 0.716 | ||||

| I encourage the development of others through stretch goals. | 0.670 | ||||

| I offer to coach others to aid their skill development. | 0.557 | ||||

| I listen carefully to the concerns of others. | 0.814 | ||||

| I demonstrate conviction in my values to “walk the talk”. | 0.802 | ||||

| I am enthusiastic about our mission for the company. | 0.769 | ||||

| I talk optimistically about the future of the firm. | 0.438 | 0.720 | |||

| I experiment and take risks even when there is a chance of failure. | 0.856 | ||||

| I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities. | 0.559 | ||||

| VARIABLE | M | SD | t a | df a | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enable | −3.25 | 1950.00 | 0.001 | 0.14 | ||

| Male | 7.17 | 2.20 | ||||

| Females | 7.47 | 2.03 | ||||

| Inspire | −3.83 | 1962.65 | 0.000 | 0.17 | ||

| Male | 7.16 | 2.36 | ||||

| Females | 7.55 | 2.22 | ||||

| Challenge | −1.45 | 2007.00 | 0.145 | 0.06 | ||

| Male | 7.18 | 2.25 | ||||

| Females | 7.32 | 2.15 | ||||

| Collective Leadership | −3.49 | 1912.26 | 0.001 | 0.16 | ||

| Male | 7.34 | 2.05 | ||||

| Females | 7.64 | 1.79 | ||||

| Authenticity | −3.26 | 2007 | 0.001 | 0.14 | ||

| Male | 3.06 | 0.94 | ||||

| Females | 3.2 | 0.87 | ||||

| Balance | −4.15 | 2007 | 0.001 | 0.19 | ||

| Male | 3.04 | 1.06 | ||||

| Females | 3.24 | 1.04 | ||||

| Challenge | 0.92 | 2007 | 0.36 | NS/0.04 | ||

| Male | 3.26 | 1.04 | ||||

| Females | 3.22 | 0.99 | ||||

| Collective KCM | −2.51 | 1945.7 | 0.01 | 0.11 | ||

| Male | 9.37 | 2.66 | ||||

| Females | 9.66 | 2.43 |

| Opting Out Shocks | % of Sample, N | Career Re-Entry Shocks | % of Sample, N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of pregnancy | 26% N = 4 | Discrimination | 53% N = 8 |

| Birth of child | 13% N = 2 | Pay inequity | 86% N = 13 |

| Miscarriage | 20% N = 3 | Difficult getting interviews | 80% N = 12 |

| Lack of flexibility after return to career from maternity LOA | 40% N = 6 | Judgement by others | 100% N = 15 |

| Geographic move | 40% N = 6 | Harassment | 20% N = 3 |

| Lack of balance | 80% N = 12 | Need for authenticity | 53% N = 8 |

| Childcare expenses | 73% N = 11 | Need for career change | 53% N = 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knowles, J.; Mainiero, L. Authentic Talent Development in Women Leaders Who Opted Out: Discovering Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020060

Knowles J, Mainiero L. Authentic Talent Development in Women Leaders Who Opted Out: Discovering Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(2):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020060

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnowles, Jennifer, and Lisa Mainiero. 2021. "Authentic Talent Development in Women Leaders Who Opted Out: Discovering Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 2: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020060

APA StyleKnowles, J., & Mainiero, L. (2021). Authentic Talent Development in Women Leaders Who Opted Out: Discovering Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge through the Kaleidoscope Career Model. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020060