The Social Media “Magic”: Virtually Engaging Visitors during COVID-19 Temporary Closures

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What types of digital content did cultural institutions implement during COVID-19 temporary closures?

- How was cultural institutions’ social media engagement affected by the types of digital content implemented during COVID-19 temporary closures?

- What digital content did cultural institutions plan to continue implementing after COVID-19 temporary closures?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Digital Content in Cultural Institutions

2.2. Social Media Engagement

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

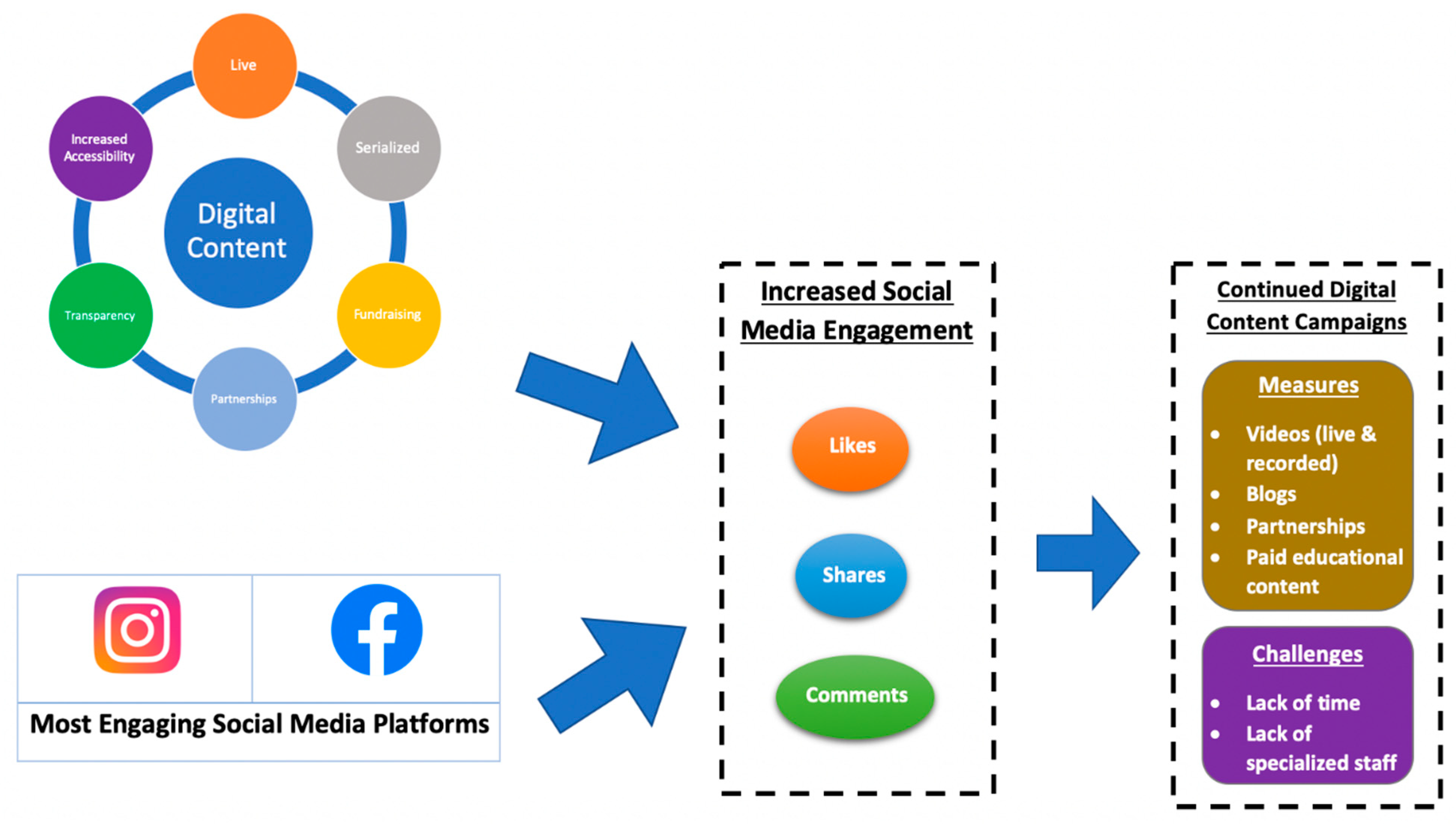

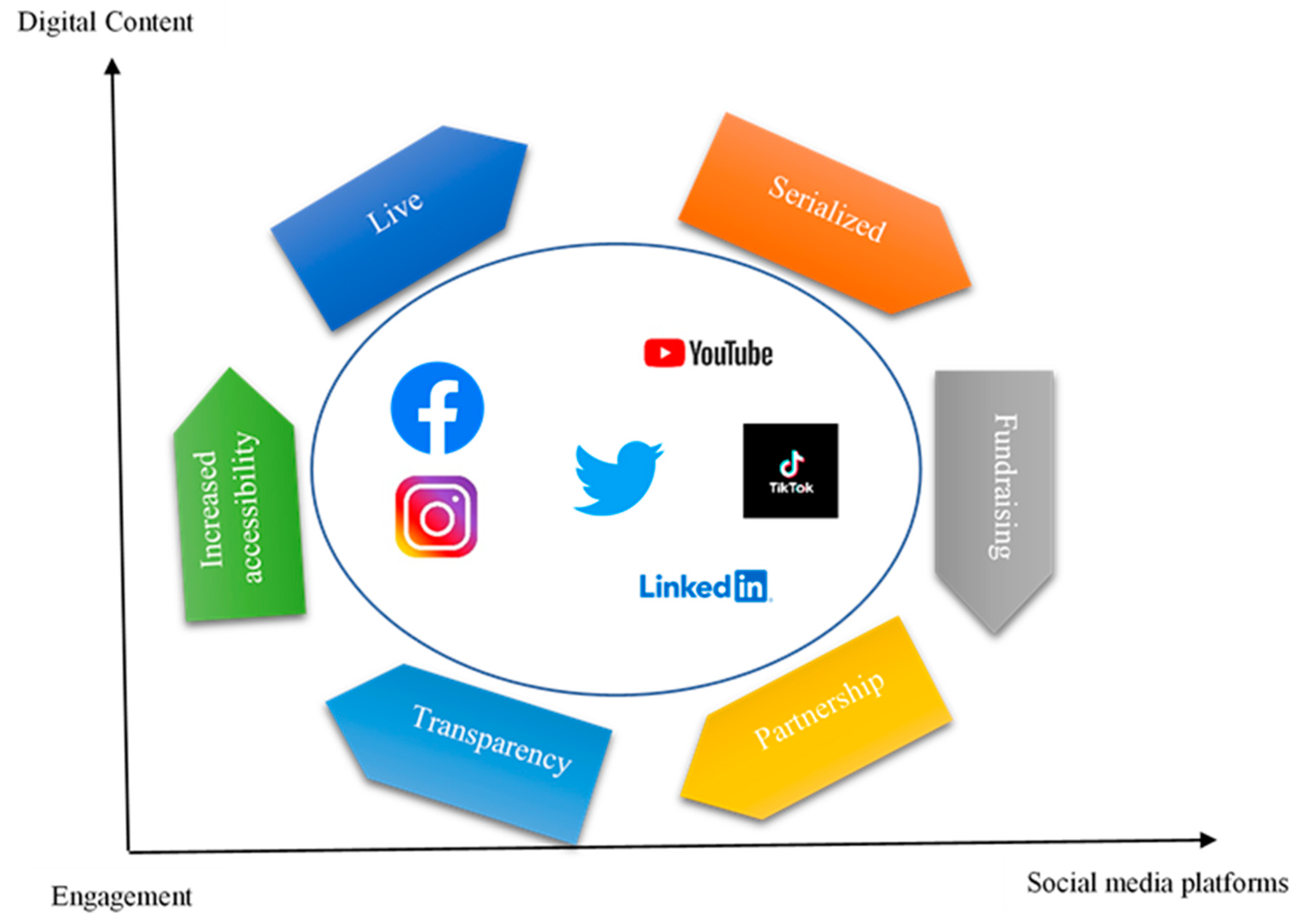

4.1. Live Digital Content

4.1.1. Serialized Digital Content

4.1.2. Fundraising

4.1.3. Partnerships

4.1.4. Transparency

4.1.5. Increased Accessibility

4.2. Social Media Engagement

4.2.1. Facebook and Instagram Became the Most Engaging Platforms

4.2.2. Measures of Social Media Engagement

4.3. The Continued Implementation of Digital Content

4.4. Challenges

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamovic, Meghan. 2013. Social Media and Art Museums: Measuring Success. Master’s thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Agostino, Deborah, and Michela Arnaboldi. 2016. A measurement framework for assessing the contribution of social media to public engagement: An empirical analysis on Facebook. Public Management Review 18: 1289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Greil, Dana, and Matthew MacArthur. 2010. Small Towns and Big Cities: How Museums Foster Community On-Line. Available online: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2010/papers/allen-greil/allen-greil.html (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- American Alliance of Museums. 2017. Museums Advocacy Day. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/programs/museums-advocacy-day/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- American Alliance of Museums. 2020. National Survey of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums [PPT]. Arlington: American Alliance of Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Asur, Sitaram, and Bernardo A. Huberman. 2010. Predicting the Future with Social Media. Paper presented at the 2010 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Toronto, ON, Canada, August 31–September 3. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, James M., and Sandra S. Graça. 2018. Humor effectiveness in social video engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 26: 158–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, David, and Roger Burrows. 2007. Sociology and, of and in Web 2.0: Some Initial Considerations. Sociological Research Online 12: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogle, Susan. 2020. What are the 7 Types of Digital Marketing? Available online: https://www.snhu.edu/about-us/newsroom/2017/11/types-of-digital-marketing (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Byrd-McDevitt, Logon. 2020. The Ultimate Guide to Virtual Museum Resources. Available online: https://mcn.edu/a-guide-to-virtual-museum-resources/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Carr, D. 1990. Qualitative Meaning in Cultural Institutions. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 31: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Linda Weiser, and Hershey H. Friedman. 2008. The New Media Technologies: Overview and Research Framework. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 20: 1408–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner. 2019. Gartner Identifies the Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends for 2020. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-10-21-gartner-identifies-the-top-10-strategic-technology-trends-for-2020 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Guest, Greg, Kathleen M. MacQueen, and Emily E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorson, Kristina, and Melissa Rach. 2012. Content Strategy for the Web. Berkeley: New Riders. [Google Scholar]

- Holliman, Geraint, and Jennifer Rowley. 2014. Business to business digital content marketing: Marketers’ perceptions of best practice. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 8: 269–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylland, Ole Marius. 2017. Even Better than the Real Thing? Digital Copies and Digital Museums in a Digital Cultural Policy. Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research 9: 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Shae Toshiko. 2017. Social Media and Museums: Reframing Audience Engagement in the Digital Communication Age. Master’s thesis, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kalay, Yehuda, Thomas Kvan, and Janice Affleck. 2008. Introduction. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage. London: Routledge, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, Suzanne. 1996. Becoming digital. Museum Management and Curatorship 15: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koiso-Kanttila, Nina. 2004. Digital Content Marketing: A Literature Synthesis. Journal of Marketing Management 20: 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch. 1977. An Application of Hierarchical Kappa-type Statistics in the Assessment of Majority Agreement among Multiple Observers. Biometrics 33: 363–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Dokyun, Kartik Hosanagar, and Harikesh S. Nair. 2018. Advertising Content and Consumer Engagement on Social Media: Evidence from Facebook. Management Science 64: 5105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, Martin. 2010. New Media: A critical Introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, Garrett Kevin. 2017. Differential Concerns: Perceived Benefits and Barriers to Visitation from the Mental Models of Museum Visitors and Non-Visitors. Master’s thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Expósito, Miriam, M. Ángeles Oviedo-García, and Mario Castellanos-Verdugo. 2017. How to measure engagement in Twitter: Advancing a metric. Internet Research 27: 1122–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, Katie Delahaye. 2011. Measure What Matters: Online Tools for Understanding Customers, Social Media, Engagement, and Key Relationships. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault, Marie-Catherine, and Elaine Mosconi. 2018. Social Media Engagement: Content Strategy and Metrics Research Opportunities. Paper presented at the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, January 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, Jennifer. 2008. Understanding digital content marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 24: 517–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Angelina, Jerry Watkins, and Susan Groundwater-Smith. 2009. The impact of social media on informal learning in museums. Educational Media International 46: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian Institution. 2001. Fundraising at Art Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Southeastern University. 2016. What Is New Media? Available online: https://online.seu.edu/articles/what-is-new-media/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Strom, Elizabeth. 2002. Converting Pork into Porcelain. Urban Affairs Review 38: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The White House. 2020. Opening Up America Again. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/openingamerica/ (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Themed Entertainment Association and AECOM. 2019. Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report. Available online: http://www.teaconnect.org/images/files/TEA_328_381804_190528.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Thomson, Kristin, Kristen Purcell, and Lee Rainie. 2013. Arts Organizations and Digital Technologies. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/01/04/arts-organizations-and-digital-technologies/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Tiago, Maria Teresa Pinheiro Melo Borges, and José Manuel Cristóvão Veríssimo. 2014. Digital marketing and social media: Why bother? Business Horizons 57: 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treem, Jeffrey W., Stephanie L. Dailey, Casey S. Pierce, and Diana Biffl. 2016. What We Are Talking About When We Talk About Social Media: A Framework for Study. Sociology Compass 10: 768–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, Richard D., Emily Burnett, Anna Lamm, and Jessica Lucas. 2009. Engaging stakeholders through social networking: How nonprofit organizations are using Facebook. Public Relations Review 35: 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Properties | Supporting Interview Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Live digital content | Facebook Live Instagram Live Livestream Events Education Comments | “We decided to do some Facebook Live videos as well as just regular video content.” (Performing arts organization A, Southeast) “We did 60 days of Facebook Live.” (Aquarium A, Southeast) |

| Serialized digital content | Themed days Themed weeks Blogs | “So each day of the week represented something different.” (Museum D, Southwest) “We actually had a health and wellness series and a weekly mindfulness series.” (Museum A, Southeast) |

| Fundraising | Donations Paid content | “Just trying to engage and thanking people for donating because we added a donate button to every single Facebook Liv.e” (Zoo A, Southeast) “They can make a donation to the aquarium and for that donation, we would send a video around 30 s long with any type of special instructions that they wanted.” (Aquarium A, Southeast) |

| Partnerships | Influencers Community partners Radio TV | “We’ve collaborated with other organizations for Facebook Live talks.” (Museum C, Northeast) “We work with local artists in the community and they just kind of took us, took our audience on a tour of their studio, and those were doing really well.” (Museum B, Southeast) |

| Accessibility | Geographical Financial Health | “It’s a way to reach schools that aren’t in-state so we can reach a larger audience.” (Zoo B, Southwest) “They’re not gonna be able to come for a while or they live out of state, but they want to support us. And so the virtual is a way to engage those people differently.” (Museum E, Southwest) |

| Transparency | Transparency Community building Conversation | “Kind of moving towards showing more constant back and forth and transparency.” (Museum C, Northeast) “So everyone is, you know, transparent and clear with everyone just so that we can keep that really strong connection with everyone that we have.” (Performing arts organization B, Southeast) |

| Changes in engagement | Engagement changing over the course of COVID-19 | “We’ve actually seen an increase. So we’re almost up to 85,000 followers on Instagram and over 150,000 on Facebook, and on Twitter we are almost at 24,000.” (Zoo B, Southwest) “The organic content went further than it ever had.” (Museum A, Southeast) |

| Most engaging platforms | Facebook TikTok YouTube | “Facebook for sure, followed by Instagram.” (Zoo C, Southwest) “100% Instagram. That’s where our audience is most active and it’s the platform that’s growing the most for us.” (Museum B, Southeast) |

| Measures of engagement | Followers, likes, comments, views, reach, impressions, shares engagement rate, conversion rate | “We usually go off of video views, how many followers we’re up that week and then engagement.” (Zoo B, Southwest) “We pretty go by the traditional definition of likes comments, shares and clicks.” (Zoo C, Southwest) |

| Future of digital content | Reducing digital content Increasing digital content | “We’re anticipating living both in person and the digital way maybe forever, honestly.” (Museum D, Southwest) “And then our education department is also looking at virtual opportunities that will be paid.” (Museum E, Southeast) |

| Challenges | Time Resources Audience expectations | “We 100% are keeping with producing this much content only because we kind of have to.” (Museum A, Southeast) “And musicians are definitely going to get a lot busier.” (Performing arts organization B) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryder, B.; Zhang, T.; Hua, N. The Social Media “Magic”: Virtually Engaging Visitors during COVID-19 Temporary Closures. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020053

Ryder B, Zhang T, Hua N. The Social Media “Magic”: Virtually Engaging Visitors during COVID-19 Temporary Closures. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(2):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020053

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyder, Brittany, Tingting Zhang, and Nan Hua. 2021. "The Social Media “Magic”: Virtually Engaging Visitors during COVID-19 Temporary Closures" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 2: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020053

APA StyleRyder, B., Zhang, T., & Hua, N. (2021). The Social Media “Magic”: Virtually Engaging Visitors during COVID-19 Temporary Closures. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11020053