1. Introduction

This article focuses on this topic and presents a multiple case study involving four family firms that have experienced an intra-family succession from founder to the second generation. Specifically, this paper aims to answer the following research question: How can family firms’ innovation capabilities evolve from the first to the second generation?

Our exploratory study (

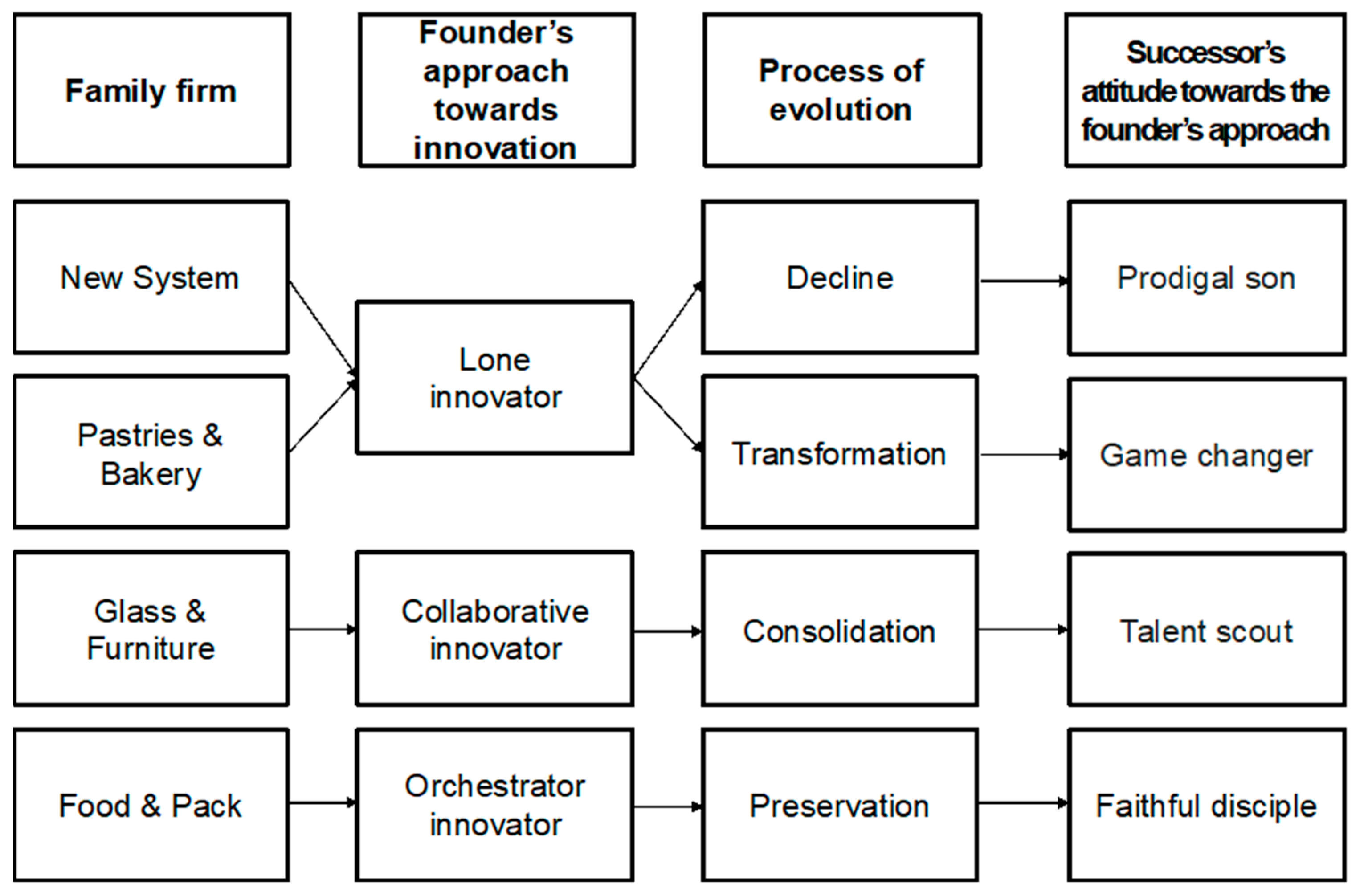

Yin 2003) has revealed four different dynamics, describing how the innovation capabilities of a first-generation family firm are or are not passed on to the second generation: decline, transformation, consolidation and preservation. Moreover, results have also revealed that these dynamics may be influenced by the founders and successors’ approaches towards innovation. Thus, to better depict differences among them, we have proposed a typology of founders (lone innovator, collaborative innovator and orchestrator innovator) and successors (prodigal son, game changer, talent scout, faithful disciple) and explained how they can influence the evolution of innovation from the founder-generation to the next.

This study provides empirical qualitative evidence for enhancing our knowledge of how family firm innovation may evolve from the first to the second generation. It shows that the founder’s approach toward innovation can deeply affect a family firm’s innovation potential when it moves to the second generation. In this way, our results respond to

Calabrò et al. (

2019)’s call for investigations into how innovation in family firms evolves over generations. Our study also responds to authors who have called for typologies to enhance our understanding of different innovation approaches in family firms (

Rondi et al. 2019;

Röd 2016;

Miller et al. 2015).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In

Section 2 we provide an overview of the literature on family firms and innovation.

Section 3 describes the research methodology, and

Section 4 presents the case studies.

Section 5 shows the empirical results, and

Section 6 concludes by discussing the paper’s contributions and also some limitations.

2. Family Firms and Innovation: A Literature Review

In analysis about family firms and innovation, many authors (

Rondi et al. 2019;

Diaz-Moriana et al. 2020) have adopted a broad and inclusive definition of innovation (

Calabrò et al. 2019), considering that it can take many forms, all marked by an element of novelty (

Johannessen et al. 2001), not just concerning research and development and technological innovation. Thus, in line with this view, we refer to innovation as all activities enabling the firm to conceive, develop, produce and introduce new products, services, processes or business models (

Freeman 1976;

Rondi et al. 2019).

During the past few decades, the number of studies analysing the link between innovation and family firms has increased substantially, and contrasting views and results have emerged. Some scholars argue that family firms are particularly innovative (

Ahmad et al. 2020;

König et al. 2013;

Kotlar et al. 2013;

Naldi et al. 2007;

Craig and Moores 2006) and identify some typical characteristics that can positively affect innovation in such firms. Long-term orientation, which is closely linked to the desire for transgenerational value transfer (

Werner et al. 2018;

Kammerlander and Ganter 2015), familiness (

Eddleston et al. 2008;

Habbershon and Williams 1999), shared family vision and goals (

Craig et al. 2014;

Sanchez-Famoso et al. 2014) and strong identity (

Casprini et al. 2017) are believed to play a key role in this regard. Furthermore, family involvement in running the firm results in a strong commitment to the company and close, business-oriented, friendly and sincere relationships (

Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), enhancing communication and promoting a culture of sharing and a climate of trust (

Dibrell and Moeller 2011)—all of which work in favour of efficient, innovative processes (

Diéguez-Soto et al. 2018). Also, family firms’ unique social capital, commonly identified in terms of their success in forging long-standing relations with other stakeholders (

Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2005), is another distinctive characteristic of such firms and may have a positive influence on their innovation propensity. Finally, long-term orientated family firms are able to establish a trust-based environment of solidarity, loyalty and credibility, creating a virtuous cycle between innovation and HRM practices whose outcomes are mutual gains for the firms and their employees (

Rondi et al. 2021).

Within this debate, scholars argue that further investigation is needed to bring out the heterogeneity of family firms and identify factors that may explain why some family firms are innovation-oriented and others are not (

De Massis et al. 2015a). For instance,

Cucculelli and Peruzzi (

2020) focus on the involvement of the family in the ownership and management of the business and consider different types of innovation (product or process-oriented innovation) over the industry life cycle. They have found that family firms are significantly more prone to introducing risky product innovations during maturity than non-family firms. Moreover, results suggest that the adoption of risky product innovation during maturity is mainly associated with family involvement in the ownership (not management). The authors argue that when external conditions undermine the survival of the business, such as during the maturity phase, and threaten the possibility of passing it on to the next generation, family owners are prone to introducing more risky innovations. Conversely, “Family management favours risk-avoiding behaviour, except in the case of experienced family CEOs” (

Cucculelli and Peruzzi 2020, p. 1).

Many concealed factors can explain this lack of uniformity in terms of innovation in family firms.

Schumpeter (

1987) ascribes a decisive role to the founder in the firm’s creative and innovative practices. During the first stages of the business lifecycle, decision-making is highly centralised by the founder, and innovation principally relies on the founder’s open innovation strategies (

Danvila-del-Valle et al. 2018). Moreover, the founder generation is widely considered less sensitive to risk and uncertainty (

Duran et al. 2016;

Werner et al. 2018;

Schumpeter 1987) since setting up a business requires a high level of risk tolerance. However, acceptance of risk is not an inherited trait (

Bertrand et al. 2008), so it is likely to be more common for founders than for later generations (

Cucculelli et al. 2016). Family firms also differ in terms of goals (

Cannella et al. 2015), the priority of the founder generation being to expand the firm—which may weigh even more heavily than the wish to maintain control of the firm (

Miller et al. 2011)—and investing in innovation is one of the main ways to achieve that goal (

Duran et al. 2016). In the same vein, other authors argue that the potential gains and losses associated with the innovation decision differ from generation to generation (

Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). On the one hand, in terms of financial (and emotional) gains and losses, the founder generation has little to lose, as the company is quite young, but a lot to gain in expanding the business. On the other hand, subsequent generations may well be more sensitive to their responsibility to preserve the company they have inherited and consequently feel greater reluctance to invest in innovation (

Werner et al. 2018).

Furthermore, some authors point out that later-generation family firms are more formalised and have more established processes, which may reduce their ability to introduce changes, even in response to external stimuli (

Westhead et al. 2002). Another possible reason behind the more limited innovation in second-generation family firms may be a desire to maintain the status quo (

Kellermanns et al. 2012) and inertia caused by past achievements when the firm was in the founder’s hands. Very often in first-generation family firms, innovation is fuelled by the founder’s knowledge and skills so that the “founder’s shadow” (

Short et al. 2009) may bind new generations to the past and discourage them from changing the usual way of doing business (

Roessl et al. 2010;

Kammerlander et al. 2015). Moreover, the founder’s knowledge is mostly tacit, not codified and shared throughout the organisation (

Kogut and Zander 1992;

Polanyi 1963). As a consequence, it can hardly be transferred to later generations, so that the founder’s exit may leave the company without the innovative energy displayed during the first generation.

However, in their studies about Slovakian family firms,

Urbaníková et al. (

2020) highlight that second-generation family firms changed the companies’ approach to innovation and introduced more types of innovations than first-generation family firms.

Woodfield and Husted (

2017) argue that new generations can enrich the body of knowledge held by a family business by bringing in new explicit knowledge gained through education and work experience. As a result, the involvement of the new generation can act as a “catalyst of change” (

Kotlar and De Massis 2013, p. 1281) because their fresh information, knowledge, skills and experience can interact and combine with the firm’s existing legacy to propel new innovation processes. This means that later generations can act as identifiers of new entrepreneurial opportunities (

Hauck and Prügl 2015;

Salvato 2004) and as drivers of innovation (

Litz and Kleysen 2001), thereby strengthening the firm’s innovation potential (

Sciascia et al. 2013;

Zahra et al. 2007). Moreover, the non-founder generation may experience the need to establish its own style and business reputation, a transformation which often requires changes to the status quo as established by the founder (

Kepner 1991) and usher in new energies and innovation prospects.

De Massis et al. (

2016) argue that tradition may prove to be a stimulus for innovation, advancing the concept of “innovation through tradition”. Thus, while it is true that tradition can risk becoming a burden that hampers a firm’s creative and innovation progress, the firm’s innovation would benefit from a process of continuous evolution if the new generation were able to exploit and build upon its legacy by supplementing it with new ideas, knowledge and skills. From this viewpoint, some scholars highlight the opportunity offered by intra-family succession to release the potential for family firms’ innovation (

Urbaníková et al. 2020;

Rondi et al. 2019;

Hauck and Prügl 2015;

Litz and Kleysen 2001). The succession process constitutes an exceptional time frame, one marked by multifarious challenges and changes that the family and the company must face (

Kotlar and De Massis 2013;

Handler 1994). For example, the founder generation must agree to hand over control to the new generation gradually and facilitate the process by guaranteeing the fullest collaboration with the successor. The latter, in turn, must be in a position to ensure the survival and continued growth of the company in the future. In this respect,

Litz and Kleysen (

2001) clarify that for intergenerational innovation to be successful, it must be prefaced by a series of carefully targeted initiatives aimed at nurturing core skills in subsequent generations. At the same time, giving the new generation scope for experimentation and responsibility will serve to promote innovation.

Other studies point out that the succession process may prove to be an opportunity to increase family firms’ social capital (

Laforet 2013), understood as the sum of knowledge and skills in the firm’s possession. This capital may lie with the family members, with non-family members or may result from the interaction of family and non-family members. The founder generation usually involves family employees in innovation projects, but as firms gradually expand and become more complex over time, the endowment of knowledge inherited from the previous generation may no longer be sufficient to fuel family firms’ innovation. As a result, later generations need to be much more open to cooperation with external human capital (

Salvato and Melin 2008;

Laforet 2013). In fact, non-family social capital can furnish professional skills that are unavailable within the family itself, besides providing access to a wide range of resources suited to promoting family firms’ innovation (

Sanchez-Famoso et al. 2019;

Chua et al. 2012;

Adler and Kwon 2002). In this regard,

Feranita et al. (

2017) maintain that collaborative innovation can significantly enhance family firms’ innovation potential. It can enable them to overcome internal limitations and tap into the knowledge, technologies and information of other organisations. However, the family firm’s generational stage can modify this attitude, and

Pittino et al. (

2013) find that propensity toward inter-organisational cooperation increases in second and later generation family firms.

Kreiser et al. (

2006) suggest that competitive pressures experienced by family firms over time often force these companies to embrace a more entrepreneurial posture during the latter stages of their life cycle. Other authors suggest that long-term survival, especially through multiple generations, would require renewal through innovation to avoid failure. Similarly, and following

Rondi et al. (

2019),

Sanchez-Famoso et al. (

2019) maintain that conditions to “unlock the innovation potential reside not only in the relational characteristics of the family system but also in the social interactions with non-family members.” They also argue that the driving force behind innovation in family businesses stems from the relationship between family and non-family social capital, which may account for the greater attention paid to family firms’ innovation (

Duran et al. 2016;

Röd 2016).

In conclusion, how succession can influence innovation in family businesses is a widely debated topic and research conducted so far has offered not always unanimous viewpoints and conclusions. This prompts questions about the circumstances under which a transition from the first to the second generation can leave family firms’ innovation unchanged or even represent an opportunity to enhance firms’ ability to introduce innovations in terms of new products and services, markets and processes, technologies and/or materials (

Jaskiewicz et al. 2015).

This article focuses on this topic and presents a multiple case study involving four family firms that have experienced an intra-family succession from founder to the second generation. This paper aims to explore how family firms’ innovation capabilities can evolve from the first to the second generation and understand which conditions may favour or hamper this change. Our analysis has revealed four different dynamics, i.e., four processes that characterise how a first-generation family firm’s innovation capacities are or not passed on to the second generation: decline, transformation, consolidation and preservation. Moreover, results also show that these dynamics are influenced by the founders and successors’ approaches towards innovation. Thus, to better depict differences among them, we propose a typology of founders (lone innovator, collaborative innovator and orchestrator innovator) and successors (prodigal son, game changer, talent scout, faithful disciple) and explain how they influence the evolution of innovation from the founder generation to the next.

This study provides empirical qualitative evidence for enhancing our knowledge of how family firm innovation may evolve from the first to the second generation. It shows that the founder’s approach toward innovation can deeply affect a family firm’s innovation potential when it moves to the second generation. In this way, our results respond to

Calabrò et al. (

2019)’s call for investigations into how innovation in family firms evolves over generations. Our study also responds to authors who have called for typologies to enhance our understanding of different innovation approaches (

Rondi et al. 2019;

Röd 2016;

Miller et al. 2015). This paper aims to explore this subject.

3. Methodology

A qualitative approach is particularly appropriate, given the focus on the “how” and “why” questions (

Yin 2003). Moreover, a wide consensus exists in family business literature on the usefulness and effectiveness of case studies to advance knowledge in this research field (

De Massis and Kotlar 2014). This method enables researchers to investigate complex phenomena, examine in-depth real-life current events and observe the meaning of people’s experiences. Therefore, it is instrumental in studying the succession process, in which several variables, such as the main actors’ behaviours, can greatly affect the process and its outcome (

Nordqvist et al. 2009). Finally, the use of exploratory case studies is recommended to family business scholars “to gain an understanding of how organisational dynamics or social processes work” (

De Massis and Kotlar 2014, p. 16). The exploratory case study method is widely used to analyse activities, processes and practices that family firms enact in dealing with innovation (

Erdogan et al. 2020;

Rondi et al. 2019;

De Massis et al. 2015b;

Kammerlander et al. 2015).

The family firms involved were selected through a purposeful case selection (

Patton 2002) based on the authors’ knowledge and contacts from previous studies. In line with our research purpose, we looked for family firms that had undergone a succession process from the first to the second generation. As a result, third and subsequent generation firms were excluded. We selected four Italian family businesses belonging to different sectors and characterised by different levels of innovativeness. They also differ in size: according to the definition of SME provided by the European Union (

European Commission 2003), they can be classified as medium (three) and large (one) companies.

We used different sources for data collection. In-depth, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews with successors were the primary sources of data. We conducted four interviews with the successors and one follow-up interview in one case. In one case, it was also possible to interview the founder, yielding a total six interviews. The interviews were conducted separately, took place at the firms’ sites and lasted between an hour and a half and two-and-a-half hours. A flexible and informal dialogue was encouraged, guided by an interview checklist. The questions aimed to collect information regarding the following aspects: demographic information about the founder, successor and family firm; the origin and history of the firm; the firm’s commitment to innovation; how the firm’s innovativeness changed over time and, namely, from the first to the second generation. All the interviews were recorded with the consent of interviewees and transcribed verbatim by the authors immediately afterwards.

With a sample of established firms (on average 37 years old), well-known in the local area, it was possible to find a large amount of secondary data. This complementary evidence was gathered from newspaper articles, online news, TV interviews, books about family firms and official websites. Furthermore, in some cases, the successors made private company or personal documents available to the interviewers. Finally, where possible, we conducted field visits in the production sites and collected field notes on the interactions of successor and founder and/or successor with other family members and non-family employees. In other cases, we took photographs (of products, documents, objects, etc.), engaged in informal conversations with family members and non-family employees and collected or consumed products. These multiple sources of data were collected to provide an effective triangulation, confirm emergent results and avoid inconsistencies in the data (

Miles and Huberman 1994).

Consistent with the practice of qualitative research, the data analysis followed an iterative approach. Available data was initially analysed to build individual case study summaries (

Miles and Huberman 1994). Subsequently, the authors cycled through multiple readings of the data and carried out a cross-case analysis to compare family firms’ experiences and identify differences and similarities concerning how the approach to innovation may evolve from the first to the second generation, including conditions affecting this evolution and consequences in terms of family firm’s innovation effectiveness and viability.

4. Case Studies

4.1. Food & Pack

Food & Pack is a large firm that operates in the flexible food packaging sector and has three different production sites. The company was founded in 1972 by Giuseppe Pesatori and his daughter Maria. However, from the very beginning, only Maria led the company, proving to be very skilful and showing excellent management and leadership skills, intuition, sensitivity and strategic vision. Unfortunately, Maria Pesatori had an administrative background, which represented a significant limitation since the company operated in a sector where technology played a critical role.

To overcome this limitation, Maria Pesatori realised that it was necessary to hire engineers and technical experts to fill roles that required highly qualified and specialised skills that she was not equipped with.

Lucia Pesatori remembers that her mother used to say: “We have to fill this empty box with value. We have reached a certain point, but this is our limit. And how can we go forward if we do not find someone to guide us?” Lucia stated: “Even though she was a creative woman, she understood that more qualified skills were necessary”. Maria Pesatori was very aware of her knowledge and limited competence. She realised that the involvement of external subjects with specialist know-how was the best way to guarantee the company’s longevity over time. Furthermore, she was convinced that the family should take a step back and leave the governance roles to managers and external directors. For this reason, she entrusted the role of CEO to a non-family manager and only played the role of chairman of the board.

Thanks to these experts’ skills, in the following years, the company increased its size and implemented important innovation processes: introduction of new and more sophisticated technologies, new products, new warehouse management systems and new information systems. Since then, the company has always maintained a strong innovative orientation. The company has also created an R&D and business development centre in charge of discovering new materials and new technologies, as well as new management procedures and systems.

The generational transfer has not altered the company’s innovative orientation. Lucia Pesatori—Maria’s only daughter—joined the company in 1995, immediately after graduating in economics. After a long period of training and learning within the company, in 2018, Lucia Pesatori took over the role of chairman of the board, taking the place of her mother, who became a simple director.

The existence of a well-established managerial structure undoubtedly facilitated the succession process, which took place gradually and without trauma, thanks to a governance structure that freed the company from depending on a single person. In her new role as president, Lucia Pesatori continued to play her role by minimising the family interference in company decisions and limiting herself to overseeing the main corporate strategy decisions.

Lucia Pesatori also continued on with the formula her mother adopted: selecting prepared and competent directors and managers externally to equip the company with qualified skills in line with the company’s needs. Even though Lucia does not possesses specialised technological skills, thanks to this formula, the company continues to stand out for its marked innovative spirit, as demonstrated by continuous investments in technology innovation and research of new materials and new solutions to improve its products.

As Lucia learnt from her mother, “An entrepreneur necessarily has a limit, even with regard to skills […] For example, I am not able to understand the details of new technologies and new production systems. And this has confirmed that it is necessary to involve people who have this kind of competence […] It definitely work[ed] in favour of the company’s growth”.

4.2. Pastries & Bakery

Pastries & Bakery is a medium-sized firm located in the Marche region. It was founded in 2002 by Giovanni Seri and his wife, Marina. The company operates in the food sector, producing traditional pastries and organic bakery products and exports throughout Europe and the USA. In 2015, their first-born Alberto took over the role of CEO. In 2019, their second child, Luigi, also joined the business as the production manager.

Giovanni and Marina decided to start their own business after working for many years in a small food production and direct sales company. They aimed to produce products of the highest quality, similar to homemade ones. They also aimed to sell them not only locally but also regionally. Giovanni mainly focused on the production process: he created ground-breaking machinery by himself to make pastries, developed innovative recipes and selected the best raw materials. Marina followed the administration. Their clients really appreciated their products, and thanks to word of mouth, the company has grown in a few years, selling not only in the Marche but also in neighbouring regions. However, Giovanni was not prepared to manage a business much bigger and complex than he expected. As stated by Alberto, “There were many difficulties from an organisational and strategic point of view. My father’s talent is making the highest quality product. He was born and raised with this goal and achieved it with excellent results. But he doesn’t have enough managerial skills to run a growing company”.

Giovanni realised that he needed help navigating the challenging growth process and initially tried to call on external advisors. However, the real change began when Alberto joined the company. Giovanni’s son has occasionally worked in the family business since he was fourteen during each summer holiday. He decided to join permanently immediately after graduating in business administration. “My brother and I, as soon as we graduated, decided to come here”, Alberto explained, “We had different opportunities. Perhaps we would have liked to develop other dreams or ideas. Nevertheless, for both my brother and me, there was a strong call of conscience. We have seen all our parents’ sacrifices to develop this company, which is our family’s pride and joy. Knowing the problems that the business experienced during its growth phase and all the potential development it could still grasp, we had a strong call of conscience, which made us say: “We can’t do anything else, and we have to join the family firm””.

Alberto assumed the role of CEO after a year and a half. When he entered the company, an in-depth process of innovation began: “The innovation came with my engagement. […] when I started to take a good look at all the processes inside and outside the company, there were two things I was absolutely sure of: firstly, the undoubted quality of the products that had to remain the same or, at least, increase; secondly, every process and everything that revolved around the business needed to be improved. And that’s what we’ve done over the years”.

The innovation involved all the company’s main areas and processes: supply chain, production, logistics, sales, marketing, communication, management control, administration and finance. Furthermore, new partnerships with universities and other companies were promoted, aiming to realise R&D projects, advance the production processes, enhance traditional products and introduce new products. Finally, the company has undertaken a process of internationalisation, exporting first in Europe and more recently in the United States.

Thanks to his strategic vision, managerial competencies and skills, Alberto was able to review the firm’s strategy and business model, turning a traditional small business into a medium-sized innovation-oriented company. To this end, combining the father’s experience with other (internal and external) sources of knowledge was essential: “During the succession process I observed my father, a lot, everything he did, his characteristics and behaviour and activities. I tried to understand everything that made him unique in what he did and make it mine. Then, I changed all the rest. I educated myself with the help of other people, other collaborators and other experiences, and developed my sensitivity, which allowed me to shape my character and have a vision for business growth”.

4.3. New System

New System is a medium-sized business that was founded in 1981 by Gregorio Volponi. It operates in the machinery industry and creates systems and equipment for the building market. New System’s products are distributed worldwide: Central and South America, Africa and Asia. In 1998, Gregorio’s daughter–Alberta—joined the business to assure the firm’s continuity in the hands of family. In 2015, the succession process was concluded, and Alberta assumed the leadership of the company, and the founder left the company.

From the beginning, the only main point of reference for the entire business and its stakeholders was the founder, who was directly involved in the engineering, production and commercialisation of the machinery, with the support of a few key collaborators who operated exclusively under his direction.

With a strong innovative and farsighted spirit, the founder created a special product—a highly innovative building system—that was the main source of competitive advantage for the company over the years. In his daughter’s words: “My father is a curious and creative man, he has it in his blood; when he finds a problem, he thinks it needs to be solved … he has the right intuition at the right time and the ability to look beyond the problem”.

Thanks to the founder’s propensity for innovation, the company was granted a wide portfolio of national and international patents (about 30 patents regarding the product and the building process). An R&D office with qualified engineers and technicians was created, and a wide network of international relationships and partnerships with key customers was developed. However, his substantial innovative footprint was combined with a particularly centralised and self-referential leadership style that was not always willingly accepted by his older collaborators.

In 1998, Alberta, after graduating in economics and working for three years as an accountant, decided to join the business and follow in her father’s footsteps. This led to a period of close intergenerational collaboration during which Gregorio tried passing on both his leadership style and the knowledge of the product and process that he had gained during decades of experience to Alberta. Nevertheless, for Gregorio, sharing the decision-making was not simple. He was used to deciding and managing the business all by himself, and it was not easy for him to learn how to involve his daughter in decision-making. Moreover, the difficulties arising from the gap between the technical skills and innovative spirit of father and daughter emerged very quickly. Alberta declared: “My main difficulty is that I don’t know the product so well. For my father, the product is an extension of himself, but it’s just a product to me. I need time to acquire his sensitivity. He has it by nature, while I have to get it through experience”.

In the following years, Alberta gained sufficient experience to compensate for her initial lack of sensitivity and at least partially bridged the gap.

In 2015, his daughter took full control of the company leadership. Following in her father’s footsteps, Alberta adopted a strongly centralised and controlling style of leadership, without having the innovative and creative orientation that characterised the founder. Under Alberta’s leadership, some activities considered innovative and necessary to enhance the business were carried out. She said, “We have filed new patents relating to the machinery manufacturing process, implemented new marketing strategies and professionally managed the production and sales department”.

Although Alberta was managing a company with strong innovative potential (the heritage left by her father), her choices in terms of innovation proved ineffective in maintaining and developing an organisation that suffered a gradual deterioration in its market competitiveness over the years. Moreover, her low propensity to delegate limited and hindered the work of highly qualified professionals to the point that some of them, in the absence of decision-making autonomy, decided to abandon the company.

4.4. Glass & Furniture

Glass & Furniture is a medium-sized Italian company that was founded in 1973 by Enrico Guglielmi. Even though he was still young, he had a lot of experience in glass processing and had already created other small firms to produce coloured glass for the furniture industry. It was precisely the profound knowledge of the glass accumulated in those years that gave him a particularly innovative idea. In fact, with the birth of Glass & Furniture, Enrico Guglielmi decided to use glass for more than just two-dimensional sheets, to be used for doors, tops and other simple decorative elements. He decided to produce furnishing items entirely made of curved glass sheets.

From the beginning, Enrico Guglielmi decided to sell his products to high-end customers who appreciate the uniqueness of Glass & Furniture products and their high quality. This choice proved to be successful and allowed Glass & Furniture to increase its sales and expand its market. However, even in the international market, he was successful thanks to collaboration with famous international designers and architects—e.g., Arad, Hasuike, Starck. The latter designed unique and refined products, which were produced by Glass & Furniture, thanks to its advanced production skills and Enrico Guglielmi and other glassmakers’ in-depth knowledge of glass.

In the following years, process innovation and product innovation continued in parallel, often influencing each other. In many cases, it was the profound knowledge of glass, together with Glass & Furniture’s advanced production skills, which suggested to designers innovative technical solutions, with which they were capable of creating innovative products. In this way, products of particular value, sometimes even with a high artistic value, were created. Some of them were even exhibited in famous international museums of modern art. They were the result of the rich endowment of internal skills related to glass processing, which Enrico Guglielmi was able to accumulate in Glass & Furniture. In fact, he was able to create a team of “master glassmakers”, who combined craft skills and technological knowledge, and who together were able to carry out a continuous process of products and processes innovation, as well as experiment with new ways of processing glass.

In 2014, Enrico Guglielmi gave the reins to his son Gabriele, the current CEO of Glass & Furniture. Gabriele has a degree in engineering, and under his leadership, the company has been enriched with new skills and has continued to experiment, innovate and do research.

The generational transition has left the DNA of Glass & Furniture unchanged. The company continues to renew its products and propose new ways of using glass, thanks to a virtuous combination of internal and external skills.

The successor did not share the founder’s creativity. However, like his father, Gabriele continues to invest in collaboration with external parties—mostly artists and designers—from which Glass & Furniture receives continuous innovative ideas: “Our research continues to be nourished by collaboration with artists […] because we offer the techniques necessary to create artworks that are also very bold from a technical point of view. So, sometimes we become an “art foundry”.

At the same time, the company continues to search for new technological solutions and fuel the development of internal production skills, including a mix of technology and craftsmanship. Gabriele often repeats: “We are numerical control craftsmen”.

In recent years, these efforts have given rise to new glass interpretations, and glass acquires unusual and very innovative features: “We are developing our production activities; we are introducing new processes, such as metallescent paints. It gives glass an effect that looks metallic. We use it to make glass furniture, but they look like metal or wood”.

5. Results

The empirical analysis reveals that family firms’ innovativeness may evolve from founder to successor through four processes (see

Figure 1): it may remain “as is” through a preservation process or may change by decline, transformation or consolidation. Exploring these evolution processes, we noted that the occurrence of one dynamic rather than the other was influenced by the founder and successor’s approach to innovation. Thus, aiming to depict different approaches better and how they may influence the evolution of the family firm innovativeness over generations, we developed and described an empirically based typology of founders and successors’ ideal types. Specifically, we identified three founder profiles—lone innovator, collaborative innovator and orchestrator innovator—and four successor profiles—prodigal son, game changer, talent scout, faithful disciple. The first typology shows diverse founders’ approaches to innovation. At the same time, the second focuses on the successors’ approaches towards innovation, also considering how they are similar to or different from those of the founders. In this vein, the analysis allowed us to identify different dynamics of innovation evolution from the first to the second generation, highlighting how the innovation capacity of the family firm evolves is influenced by the attitude, action and behaviour of founders and successors. The typologies identified are important because they help us understand the differences among profiles and how each ideal type may influence the evolution of innovation in family firms from the founder generation to the next. The founders’ typology, the processes of evolution and the successors’ typology are described and discussed in the following paragraphs.

5.1. Founder’s Approach to Innovation: Lone Innovator, Collaborative Innovator and Orchestrator Innovator

With regard to the first point, the case analysis reveals three different founders’ approaches toward innovation, ranging from an entrepreneur-centred approach to a teamwork-oriented approach (

Harper 2008): lone innovator, collaborative innovator, orchestrator innovator.

The founders of New System and Pastries & Bakery can be described as “lone innovators”. They had strong intuitive and creative skills and acted independently in introducing new products and new processes. Moreover, they possessed advanced technical skills, which allowed them to carry out process and/or product innovations autonomously. However, they were not concerned with spreading their innovative capacities throughout the company and were not interested (New System) or unable (Pastries & Bakery) to develop a team to support the innovation process. For this reason, they can be described as lone innovators. Lone innovators act on their own; they innovate independently and do not share their knowledge with others. They are the only drivers of innovation processes and are the only ones that possess the needed knowledge and skills to innovate.

In Glass & Furniture, the founder began his experience as a lone innovator. He was very familiar with glass processing, and his advanced technical skills, combined with his creativity and intuitive abilities, allowed him to carry out important process and product innovations. However, over time, he changed his approach to innovation and was able to evolve, becoming a “collaborative innovator”. He started to collaborate with others—inside and outside the company—and created a team of experts who provided new skills and competencies complementary to his own. Belonging to a team provided new stimuli and gave great impetus to subsequent innovations. He continued to play a crucial role as the leader of the innovation process, and his innovative ideas and projects were shared with his collaborators. As a result, his role changed over time, and in the second part of his experience, he became the leader of a team with diverse knowledge and skills. The team members’ role was crucial as they supported the founder in realising his innovations and also interacted with him in shaping new ideas and boosting further innovations. In such a way, innovation became a shared process, based on the collaborative innovator’s ability to involve qualified experts, aiming to create a team and communicate, delegate, share knowledge and decision processes with them.

Finally, the founder of Food & Pack can be defined as an “orchestrator innovator”. As the case shows, she was not directly involved in introducing new products and processes from the very beginning. The founder of Food & Pack was very concerned with innovation and was well aware of the importance of technological innovation. At the same time, she was well aware of her limited technical skills and knowledge. Therefore, her main focus was to fill this gap by hiring engineers and experts to build a highly qualified and innovative organisation. In this context, she played a crucial role as an orchestrator. Acting as an orchestrator means not being directly involved in the execution of music yet playing a decisive role in choosing the music to play and selecting the right conductor and musicians. Likewise, the founder of Food and Pack acted as an orchestrator innovator. Her key task was to anticipate their main goals, understand key resources the business needed and provide them correctly. In this role, she did not need to possess superior knowledge or innovation abilities, even though her ability to display a clear strategic vision to lead the business and a strong intellect in building a professional organisation in which she can delegate innovation processes were crucial.

5.2. How the Approach to Innovation May Evolve from the First to the Second Generation

Turning to the second point, results show that the approach to innovation imprinted by the founder did not always remain unchanged: it can be preserved “as is” or changed following diverse dynamics (decline, transformation or consolidation) with the second generation. These processes are described in the following part, also explaining that individual and organisational conditions may influence this evolution. Finally, related consequences in terms of innovation effectiveness and viability of family firms are described.

New System was characterised by a dynamic of decline, as the successor was unable to perpetuate the same approach to innovation. The result was a drastic decrease in the company’s innovation capacity and effectiveness. Which conditions shaped this dynamic? Both individual and organisational factors can be identified to explain such a decline. On the one hand, the successor was not as competent and skilled as the founder was in technology and engineering, which prevented her from replicating her father’s experience and being equally effective as a lone innovator. At the same time, she was also unable to change her father’s approach to innovation and move from an entrepreneur-centred approach to a teamwork-oriented approach. The founder had not spread his spirit of innovation throughout the organisation, and the successor inherited a business that had been deprived of its innovative drive. Indeed, she hired some engineers and tried to stimulate them to innovate. However, she failed to be an effective team leader and was unable to value their contribution because she was not willing to grant them the necessary autonomy and allow them to be free to exploit their innovative potential. In conclusion, in New System, the skill gap caused by the founder’s exit was bridged neither at an individual level nor at an organisational level. Consequently, innovation effectiveness declined. The founder’s ability to introduce innovation with success faded over time, hampering the business’s innovation and viability.

Conversely, in the case of Pastries & Bakery, the approach toward innovation was characterised by a radical transformation. The successor was able to change the founder’s approach, developing from a lone innovator to an orchestrator-innovator approach. The successor introduced several innovations, favouring a process of professionalisation, improving the whole organisation and developing external networks to gain new knowledge, skills and competences. Which conditions allowed such a radical transformation? He demonstrated a strong commitment, motivated by the deep bond with the family and the firm and driven by the willingness to exploit the business’s full potential. The successor was also an active agent during the succession process. He observed the founder’s approach: to realise excellent quality products on his own in the predecessor’s mind was a fixed idea, and all his efforts were oriented to reach this goal. The successor gained “the good part” of the founder’s innovation approach—do your best to achieve the highest quality—but profoundly changed all the rest. The acquisition of relevant competencies and managerial skills thanks to a qualified and specialised education, combined with the interaction with external experts and key collaborators within the business, were crucial. Therefore, in this case, the evolutionary process of the founder’s approach was shaped by particular conditions that triggered the spread of innovation throughout the firm. They have been the indispensable premises for developing an organisation widely oriented to innovation and enabling its growth.

In Glass & Furniture, a process of consolidation emerged. The successor was able to preserve and enhance the approach of co-innovation introduced by the founder, continuing to involve external experts as sources of knowledge and introducing new processes and products developed. He was able to combine internal and external skills and also enable the whole organisation to interiorise, maintain and reinterpret the founder’s approach to innovation. Which conditions allowed the successor to consolidate the founder’s approach to innovation? Even if the successor did not share the founder’s creativity, the interaction and collaboration between founder and successor within the professional team during the succession process was essential to share and transmit relevant and often tacit knowledge. The successor learned and consolidated the ability to leverage on an external and internal pool of competencies, knowledge and skills, thus compensating for his incapability. Specifically, he was particularly able to collaborate with experienced designers and architects and thus obtain creative skills that combined synergistically with his technical-engineering abilities. Thanks to this approach, the company has not only remained innovative but its potential has exploded.

Finally, Food & Pack was characterised by a dynamic of preservation. In fact, the successor decided to adopt the same approach as her predecessor, maintaining the role of an orchestrator innovator. Why? Diverse possible explanations emerged. First, the successor was fully aware of her strengths (e.g., knowledge of the business, managerial competencies, propensity to delegate decision-making processes, etc.) and weaknesses (e.g., limited technical skills and technologies knowledge). Second, the predecessor and successor shared the same vision and values about the family business: external expertise was considered a key resource for business, and family owners should step back from some decision-making, leaving room for qualified managers and directors. Mother and daughter were, in fact, convinced that if you do not have adequate skills, delegating tasks to more qualified people and finding the right person for the right job is better. The approach to innovation adopted by the predecessor continued to prove its efficacy with the successor: the organisation maintained its innovative spirit, allowing for the business’s development and viability.

5.3. The Successor’s Attitude toward the Founder’s Approach: Prodigal Son, Game Changer, Talent Scout, Faithful Disciple

Concerning the third point, results showed that successors may assume four different attitudes toward the founder’s approach to innovation. To describe this heterogeneity, we proposed a typology of four ideal types of successors labelled as follows:

The prodigal son;

The game changer;

The talent scout;

The faithful disciple.

As in the parable, the prodigal son refers to successors that dissipate the heritage—in terms of innovation capabilities, in this case—received from the founder and are not able to find their own way to innovation. At New System, the founder was used to deciding, managing and innovating by himself. For him, it wasn’t easy to share his tacit knowledge with his daughter and involve her in his decisions, ideas and innovation processes. During the succession process, the successor learned to do it by herself, centralising the decision-making process, developing a strong sense of control and low propensity to delegate. Unfortunately, however, she did not have the same capacity for innovation as her father, nor was she able to benefit from the involvement of other skilled subjects. Moreover, in the family firm’s reality, the prodigal son cannot go back to their father. Thus, what remains is just a company stripped of its innovativeness.

The game changer refers to a successor who takes charge of the situation and sets up the game by defining new rules. This is the case of Pastries & Bakery, where the founder adopted an approach mainly oriented to develop innovation individually, but the successor realised that in order to make the quantum leap, it was necessary to move up a gear and change the founder approach by switching from a lone innovator to an orchestrator innovator approach.

The talent scout relates to successors who learn and adopt their fathers’ behaviours but do not merely replicate them in the same way. They look for new talents and experts to complement their (limited) innovation capacities and explore new collaboration opportunities to keep the company’s innovativeness vibrant. Such is the case of Glass & Furniture, where the founder created innovative and high-quality products and engaged other experts. The successor interacted with the founder, providing important new skills and stimulating new innovative ideas. At the same time, the founder involved his son in this innovative atmosphere, allowing him to learn how to interact and manage the team of experts. In the end, the student outperformed the master, not in terms of creative genius but in leveraging the talents of others to generate innovation.

Finally, the faithful disciple carries on the founder’s approach “as is”, without substantial changes. This applies to Food & Pack, where the successor acquired the founder’s approach to innovation, based on a delegation process in a well-structured organisation, and decided to maintain the same approach, continuing to act as an orchestrator innovator.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper aimed to explore how family firms’ innovation capabilities may evolve from the first to the second generation. From the multiple case analysis, four different dynamics of evolution emerged: decline, transformation, consolidation and preservation. Furthermore, results pointed out that the diverse founders and successors’ approaches towards innovation are paramount in determining which kind of evolution process may occur. Specifically, we identified three different approaches adopted by founders (lone innovator, collaborative innovator and orchestrator innovator) and four profiles with regard to successors (prodigal son, game changer, talent scout, faithful disciple). These typologies allowed us to better highlight differences among their approaches and explain how they may influence the evolution of innovation from the founder generation to the next. Finally, positive or negative consequences in terms of innovation effectiveness and the family firms’ viability were also described.

Our findings further the debate on family firms and innovation by analysing the various founders’ approaches toward innovation, how they may evolve from the first to the second generation and how successors may act toward the founder’s approach. In light of this, we have responded to

Calabrò et al. (

2019) who called for research on how innovation in family firms evolves over generations and to authors who called for new typologies to widen knowledge of different innovation approaches (

Rondi et al. 2019;

Röd 2016;

Miller et al. 2015).

Moreover, prior studies underline that the founder’s exit might result in the decline of the company’s innovativeness because of the “founder’s shadow” effect (

Short et al. 2009), the subsequent generations’ inertia and desire to maintain the status quo (

Roessl et al. 2010;

Kellermanns et al. 2012;

Kammerlander et al. 2015), and difficulties in transfer of the founder’s tacit knowledge to later generations (

Kogut and Zander 1992;

Polanyi 1963). Our results confirm this empirical evidence, adding that this is especially true when founders act as lone innovators, adopting an entrepreneur-centred approach to innovation. In this case, the innovation capacity of the company is concentrated on one person. Consequently, when the founder leaves the company, successors take over a company that has been deprived of its innovative drive and the firm’s innovation potential risks vanishing. This result can be avoided if successors are able to—directly or indirectly—nurture or recreate the innovative drive that was lost with the founder’s exit. From this point of view, successors’ education does not seem to play a decisive role (the successors in the analysed cases are all graduates). Moreover, even though the successors do not possess the same technical skills as the founders and do not match their genius or creative capacity, companies could be just as innovative in the second generation. As some of our cases show, this can happen when successors are able to aggregate and coordinate a pool of internal and/or external competencies, knowledge and skills, thus compensating for their low innovation capabilities. Otherwise, if these conditions are not in place and the successors do not have the same creative genius as the founders, the company’s ability to innovate is bound to fade. In such cases, successors may behave like prodigal sons, dissipating the innovation potential generated by the founders and causing the business to decline.

At the same time, this study confirms the opportunity offered by intra-family succession to “unlock” (

Rondi et al. 2019, p. 1) the potential for family firms’ innovativeness (

Hauck and Prügl 2015;

Litz and Kleysen 2001). The second-generation family firms may introduce more types of innovations than product or process ones (

Urbaníková et al. 2020), and be more open toward inter-organisational cooperation (

Pittino et al. 2013). From this perspective, successors may behave as game changers and act as “catalyst of change” (

Kotlar and De Massis 2013, p. 1281). Moreover, our results show that, in this case, successors must be active agents and their self-empowerment, self-efficacy and self-awareness prove to be essential to succeed. They must be able to take the situation in hand and be aware that moving from the lone innovator’s logic to the orchestrator innovator is fundamental to continue to nurture and indeed grow the firm’s innovativeness. They must also have the right management skills and culture to bring about change and be capable of identifying new entrepreneurial opportunities (

Hauck and Prügl 2015;

Salvato 2004) and strengthening the firm’s innovation potential (

Sciascia et al. 2013;

Zahra et al. 2007).

Furthermore, our results highlight the crucial role of interactions with non-family social capital (

Rondi et al. 2019;

Sanchez-Famoso et al. 2019) and cooperation with external human capital (

Salvato and Melin 2008;

Laforet 2013) to acquire professional skills otherwise unavailable among family members. They also add that it is more natural for successors to engage internal non-family members or external professionals when the founders were orchestrator innovators, thus already open and oriented to professionalising the firm and cooperating with external experts. In this case, the founders can mentor the second generation on the importance of professionalisation and cooperation as well as provide contacts with a wide network of experts who can internally or externally promote family firms’ innovation. Additionally, when the innovation is widespread throughout the organisation, it is easier for firms to keep their innovative ability even after the founders’ exit, as long as the successors are able to preserve, like faithful disciples or consolidate like talent scouts, a teamwork-oriented approach to innovation.

Summing up, founding entrepreneurs’ innovation capacity does not necessarily or automatically turn into the firm’s innovation capacity. On the contrary, sometimes, the presence of entrepreneurs who act as lone innovators can inhibit the development of innovation within the firms. An entrepreneur-centred approach can create a kind of dependence on the founder’s innovative skills. Consequently, firms become vulnerable, and the succession process can put their innovation potential at serious risk. Thus, although innovation often stems from individual genius, talent and creativity, promoting the creation of a teamwork-oriented approach to innovation is essential to turn individual potential into organisational potential, sustainable over time and generations. In addition, an open approach to innovation can allow the firm to overcome the limitation of financial resources that often characterises family businesses and limits their innovativeness, as it allows them to draw on external sources of knowledge, skills and technology (

De Massis et al. 2015b).

On a practical level, these results draw the attention of first- and second-generation family firms to the features that may characterise different approaches to innovation, how such approaches may evolve from the founding generation to the next, and what the consequences associated with different paths might be. They also emphasise the importance of the business’s professionalisation and collaboration with internal and external family members to promote and maintain the firm’s capacity for innovation.

Like other research on this topic, this study is not without limitations. The analysis considered a limited number of cases. Even if this conforms to the acceptable sample size put forward by

Eisenhardt (

1989), more empirical research is needed to further elaborate on these typologies to confirm or enrich the ideal types identified. Moreover, we have mainly focused on the individual level of the founder and the successor. However, many other variables may influence the dynamics analysed, such as different environmental contexts in which firms compete. Therefore, future research could consider the heterogeneity that features individuals and characterises environmental contexts. Finally, all data was collected by asking interviewees to reconstruct their experiences retrospectively, and reconstructions could potentially be affected by their memories’ accuracy. To better analyse the evolution of family business innovation over generations, future research could use a mixed method (retrospective and real-time) or employ a longitudinal study.