The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Assessment in the Tourism Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Family Business in Management Research

2.2. Financial Performance in Tourism Organizations

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

RQ1: What are the contributions of family members on Hotels’ performance?

RQ2: What are the relationship between ownership’s concentration and Hotels’ performance?

RQ3: What are the relationship between the family’s ownership and Hotels’ performance?

RQ4: What are the impacts related to the inclusion of family members within the BoDs?

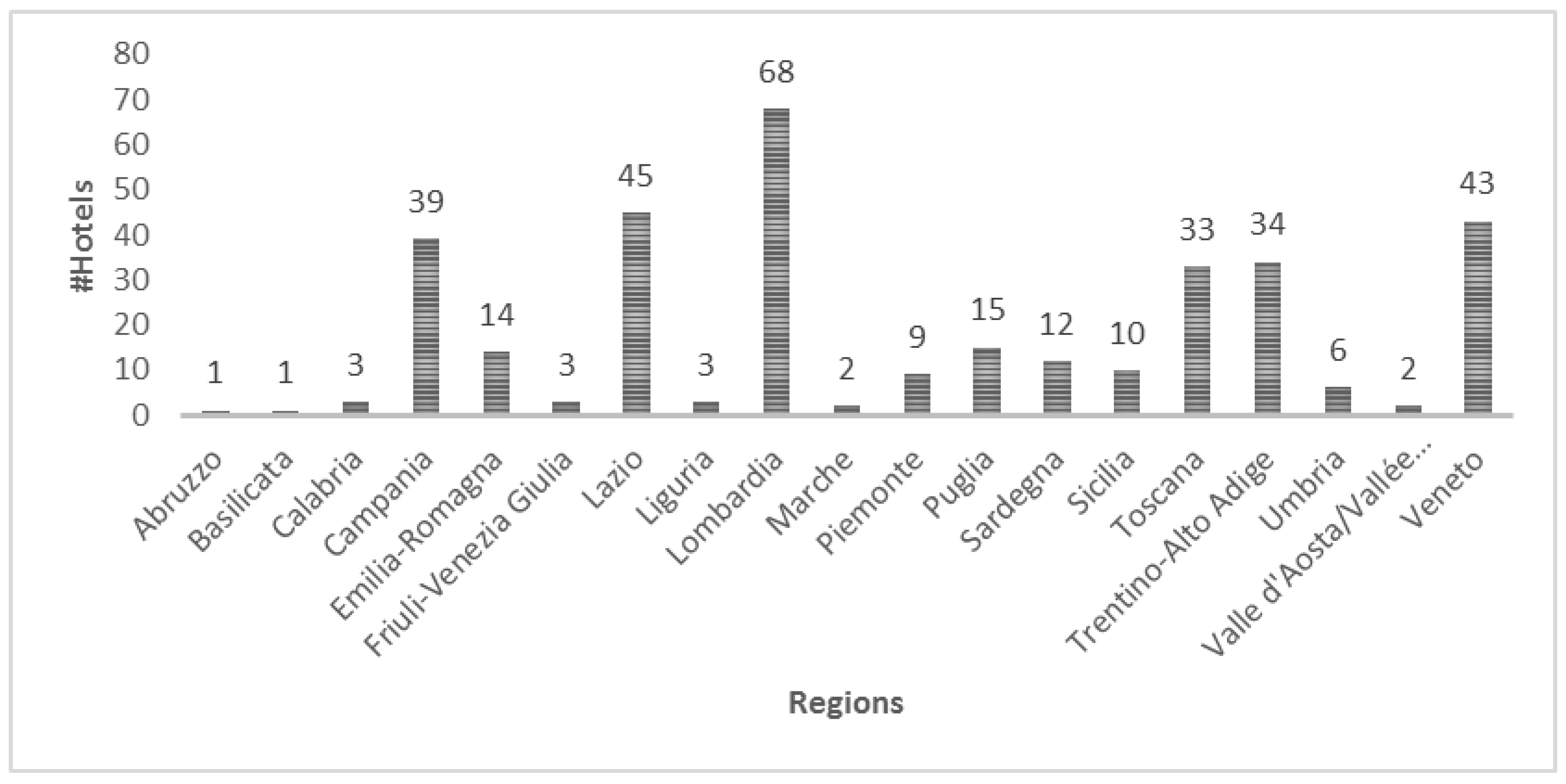

4. Sampling and Methods

5. Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguilera, Ruth V., and Rafel Crespi-Cladera. 2012. Firm family firms: Current debates of corporate governance in family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy 3: 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, Andrew A., Simplice A. Asongu, and Uju V. Alola. 2020. House prices and tourism development in Cyprus: A contemporary perspective. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, Edem M., Ben Q. Honyenuga, Marta M. Berent-Braun, and Ad Kil. 2018. Structural aspects of corporate governance and family firm performance: A systematic review. Journal of Family Business Management 8: 306–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnaresi, Davide, Francesco Maria Barbini, and Patrizia Battilani. 2019. Organizational change in the hospitality industry: The change drivers in a longitudinal analysis. Business History. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banca d’Italia. 2018. Turismo in Italia Numeri e Potenziale di Sviluppo. Roma: Banca d’Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoloni, Marzio. 2020. Il turismo resta il petrolio d’Italia: «Oltre 40 miliardi nel 2019, ora diversificare»—Il Sole 24 ORE. Available online: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/il-turismo-resta-petrolio-d-italia-oltre-40-miliardi-2019-ora-diversificare-ACTKjOCB (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Besanko, David, David Dranove, and Mark Shanley. 2000. Sustaining Competitive Advantage. New York: Jhon Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brenes, Esteban R., Kryssia Madrigal, and Bernardo Requena. 2009. Corporate governance and family business performance. Journal of Business Research 64: 280–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent Ritchie, J. R., and Geoffrey Ian Crouch. 2004. The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. Choice Reviews Online 41: 41-6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, Juan Gabriel, and Wiston Adrian Risso. 2010. Tourism as a determinant of long-run economic growth. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure & Events 2: 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Fabio, Barbara Livieri, and Andrea Venturelli. 2014. Intangibles and Value Creation in Network Agreements: Analysis of Italian firms. Management Control, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Andrea, Giacomo Marzi, Massimiliano Matteo Pellegrini, and Riccardo Rialti. 2018. Conflict management in family businesses: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. International Journal of Conflict Management 29: 519–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, Jose C., Ana M. Moreno-Menéndez, José L. Barbero, and Eric Clinton. 2019. Retrenchment Strategies and Family Involvement: The Role of Survival Risk. Family Business Review. 32: 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuogno, Simona, Claudia Arena, Alessandro Cirillo, and Luca Pennacchio. 2018. Exploring the relation between family ownership and incentive stock options: The contingency of family leadership, board monitoring and financial crisis. Journal of Family Business Strategy 9: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Kyoo Yup. 2000. Hotel room rate pricing strategy for market share in oligopolistic competition—Eight-year longitudinal study of super deluxe hotels in Seoul. Tourism Management 21: 135–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan Frank Li. 2012a. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Coles, Jeffrey L., and Zhichuan Li. 2012b. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1680484 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Colli, Andrea. 2003. The History of Family Business, 1850–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cucculelli, Marco, and Dimitri Storai. 2015. Family firms and industrial districts: Evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry. Journal of Family Business Strategy 6: 234–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, Alfredo, Josip Kotlar, Giovanna Campopiano, and Lucio Cassia. 2013. Dispersion of family ownership and the performance of small-to-medium size private family firms. Journal of Family Business Strategy 4: 166–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, Nicola, Stefano Adamo, and Francesco Giaccari. 2002. Lezioni di economia aziendale. Bari: Cacucci. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Agency Problems and Residual Claims. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 327–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 2019. Separation of ownership and control. In Corporate Governance: Values, Ethics and Leadership. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, pp. 163–88. ISBN 9781315191157. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigós-Simón, Fernando J., Daniel Palacios Marqués, and Yeamduan Narangajavana. 2005. Competitive strategies and performance in Spanish hospitality firms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 17: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, Donald, and Jack Carlsen. 2005. Family business in tourism. State of the art. Annals of Tourism Research 32: 237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccio, Vincenzo, Agostino Giannelli, and Luigi Mastronardi. 2018. Explaining determinants of Agri-tourism income: Evidence from Italy. Tourism Review 73: 216–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Phil, and Ozlem Ozdemir. 2020. Turkish delight a public affairs study on family business: The influence of owners in the entrepreneurship orientation of family-owned businesses. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illy, Andrea. 2019. Sostenibilità, felicità, net present value e dintorni. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management 37: 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, Lee, and Regena Farnsworth. 2003. Seasonality in tourism employment: Human resource challenges. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 15: 312–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Kyung Ho, Seoki Lee, and Chang Huh. 2010. Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 29: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hong-bumm, and Woo Gon Kim. 2005. The relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance in luxury hotels and chain restaurants. Tourism Management 26: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, Salih, Zeynep Kusluvan, Ibrahim Ilhan, and Lutfi Buyruk. 2010. The Human Dimension. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 51: 171–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, Jaana, and Mervi Niskanen. 2013. Behavior and attitudes of small family firms towards different funding sources. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 26: 579–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, Clive S., Jere R. Francis, and Zitian Wang. 2012. Selection models in accounting research. The Accounting Review 87: 589–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, Andrew J., Miguel Minutti-Meza, and Charles E. Wasley. 2019. Influential observations and inference in accounting research. The Accounting Review 94: 337–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Frank. 2016. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Investment Analysts Journal 45: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, M. Belén, Beatriz Martínez, and Julio Pindado. 2016. Corporate governance, ownership and firm value: Drivers of ownership as a good corporate governance mechanism. International Business Review 25: 1333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lude, Maximilian, and Reinhard Prügl. 2018. Why the family business brand matters: Brand authenticity and the family firm trust inference. Journal of Business Research 89: 121–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, Raj V., Gautam Vora, William C. McDowell, and Dmitry Khanin. 2020. Family member commitment, the opportunity costs of staying, and turnover intentions. Journal of Business Research 108: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Geoffrey, Luis R. Gómez–Mejía, Pascual Berrone, and Marianna Makri. 2017. Conflict between Controlling Family Owners and Minority Shareholders: Much Ado about Nothing? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41: 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Jimenez, Rocio. 2009. Research on Women in Family Firms. Family Business Review 22: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Jean, Sandra Dow, and Bakr Ibrahim. 2012. All in the family? Social performance and corporate governance in the family firm. Journal of Business Research 65: 1643–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, Muhammad, Solomon Nathaniel, Ghulam Shaikh, and Anoop Kumar. 2020. Energy consumption, institutional quality and tourist arrival in Pakistan: Is the nexus (a)symmetric amidst structural breaks? Journal of Public Affairs, e2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubangizi, Betty C., and David Mwesigwa. 2019. Enhancing Local Economic Development through tourism: Perspectives from a cohort of Got Ngetta rock climbers in Mid-North Uganda. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure. Available online: file:///C:/Users/MDPI/AppData/Local/Temp/article_74_vol_8_5__2019_ukzn.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Newell, Graeme, and Ross Seabrook. 2006. Factors influencing hotel investment decision making. Journal of Property Investment & Finance 24: 279–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Doron, and Stephen H. Penman. 2001. Ratio analysis and equity valuation: From research to practice. Review of Accounting Studies 6: 109–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordqvist, Mattias, Pramodita Sharma, and Francesco Chirico. 2014. Family Firm Heterogeneity and Governance: A Configuration Approach. Journal of Small Business Management 52: 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmi, Pamela, Fabio Caputo, and Mario Turco. 2016. Changing Movie! Film Commissions as drivers for creative film industries: The Apulia Case. ENCATC Journal of Cultural Management and Policy 6: 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pandikasala, Jijin, Iti Vyas, and Nithin Mani. 2020. Do financial development drive remittances? Empirical evidence from India. Journal of Public Affairs 7: 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicelli, Michela. 2016. Dall’Impresa Padronale al Value Based Management. Sei Modelli Interpretativi di un’Inevitabile Evoluzione. Economia Aziendale Online 7: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Mike. 2005. Succession in tourism familiy business: The motivation of succeeding family members. Tourism Review 60: 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, Simone, Fabio Caputo, and Andrea Venturelli. 2020. Does it pay to be an honest entrepreneur? Addressing the relationship between sustainable development and bankruptcy risk. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1478–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, Rajnish Kumar. 2016. A Co-opetition-Based Approach to Value Creation in Interfirm Alliances. Journal of Management 42: 1663–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, Antonio J., Ana Perez-Luno, and María Jesús Nieto. 2016. Does Family Involvement in Management Reduce the Risk of Business Failure? The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Family Business Review 29: 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, Pier Felice, Andrea Caputo, Donatella Valente, and Simone Pizzi. 2021. 2030 Agenda and sustainable business models in tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Ecological Indicators, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidat, Zaid, Mauricio Silva, and Claire Seaman. 2019. The relationship between corporate governance and financial performance: Evidence from Jordanian family and non-family firms. Journal of Family Business Management 9: 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif Ul Islam, Muhammad, Muhammad Saeed Meo, and Muhammad Usman. 2020. The relationship between corporate investment decision and firm performance: Moderating role of cash flows. Journal of Public Affairs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainaghi, Ruggero. 2004. La gestione strategica dei distretti turistici. Milano: CUSL. [Google Scholar]

- Sakawa, Hideaki, and Naoki Watanabel. 2019. Family control and ownership monitoring in Stakeholder-oriented corporate governance. Management Decision 57: 1712–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, Enrico, and Francesca Lotti. 2005. The survival of family firms: The importance of control and family ties. International Journal of the Economics of Business 12: 183–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, Salvatore, Pietro Mazzola, and Franz W. Kellermanns. 2014. Family management and profitability in private family-owned firms: Introducing generational stage and the socioemotional wealth perspective. Journal of Family Business Strategy 5: 131–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Susan P. 2005. Agency theory. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 263–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Piyush, Ivy S. N. Chen, and Sherriff T. K. Luk. 2018. Tourist Shoppers’ Evaluation of Retail Service: A Study of Cross-Border Versus International Outshoppers. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 42: 392–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Haiyan, and Gang Li. 2008. Tourism demand modelling and forecasting-A review of recent research. Tourism Management 29: 203–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Laura J., Remedios Hernández-Linares, María Concepción López-Fernández, and Franz W. Kellermanns. 2019. A Typology of Family Firms: An Investigation of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance. Family Business Review 32: 174–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Mary, and John Rasp. 1991. Tradeoffs in the Choice between Logit and OLS for Accounting Choice Studies. Accounting Review 66: 170–87. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe, Lutgart A. A., and Steven Carchon. 2003. Agency relations within the family business system: An exploratory approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review 11: 171–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Looy, Amy, and Aygun Shafagatova. 2016. Business process performance measurement: A structured literature review of indicators, measures and metrics. SpringerPlus 5: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, Natarjan, and Vasudevan Ramanujam. 1986. Measurement of Business Performance in Strategy Research: A Comparison of Approaches. Academy of Management Review 11: 801–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, Andrea, Salvatore Principale, Lorenzo Ligorio, and Simona Cosma. 2020. Walking the talk in family firms. An empirical investigation of CSR communication and practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, Ping-Kwong, and Chung-Ming Lau. 2005. Competitive actions and firm performance of hotels in Hong Kong. International Journal of Hospitality Management 24: 611–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yanhong, Kudzayi Maumbe, Jinyang Deng, and Steven W. Selin. 2015. Resource-based destination competitiveness evaluation using a hybrid analytic hierarchy process (AHP): The case study of West Virginia. Tourism Management Perspectives 15: 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Var. | Description | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|

| ROE | ROE is equal to a fiscal year net income (after preferred stock dividends, before ordinary stock dividends), divided by total equity (excluding preferred shares) | + |

| ROA | ROA is equal to fiscal year net income (after preferred stock dividends, before ordinary stock dividends), divided by the total asset (excluding preferred shares) | + |

| FALCON | FALCON measures the ability to meet future obligations | - |

| CRIF | CRIF gives each company a score of 1000 to 1, where 1000 indicates the most stable companies and one the most vulnerable. | + |

| VADIS | VADIS measures the propensity for a company to be bankrupt within the next 18 months. | - |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||||

| ROE | 11.27 | 25.10 | −149.65 | 125.66 | AIDA BvD |

| ROA | 2.85 | 28.81 | −341.62 | 77.19 | AIDA BvD |

| FALCON | 4.24 | 1.92 | 1 | 10 | AIDA BvD |

| CRIF | 634.92 | 142.82 | 196 | 832 | AIDA BvD |

| VADIS | 3.20 | 1.725 | 1 | 9 | AIDA BvD |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Family firms | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | AIDA BvD |

| % Shares | 80.42 | 27.09 | 0 | 100 | AIDA BvD |

| Family_power | 31.16 | 39.69 | 0 | 100 | Our elaboration |

| Family_board | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | Our elaboration |

| Control Variables | |||||

| SIZE | 9.52 | 1.31 | 5.67 | 13.75 | AIDA BvD |

| EQUITY | 8.10 | 1.96 | 2.02 | 12.96 | AIDA BvD |

| EMPLOYEES | 4.55 | 0.61 | 3.91 | 7.16 | AIDA BvD |

| D/E | 2.41 | 8.95 | −1.76 | 133.29 | AIDA BvD |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) ROE | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| (2) ROA | 0.552 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (3) FALCON | 0.356 | 0.415 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (4) CRIF | 0.510 | 0.569 | 0.712 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (5) VADIS | −0.423 | −0.314 | −0.693 | −0.560 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (6) VPI | −0.423 | −0.314 | −0.693 | −0.560 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (7) SIZE | −0.073 | −0.100 | 0.356 | 0.205 | −0.362 | −0.362 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (8) EQUITY | 0.124 | 0.093 | 0.679 | 0.402 | −0.639 | −0.639 | 0.854 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (9) EMPLOYEES | 0.051 | 0.108 | 0.242 | 0.237 | −0.413 | −0.413 | 0.660 | 0.612 | 1.000 | |||||

| (10) D/E | −0.450 | −0.268 | −0.467 | −0.279 | 0.414 | 0.414 | 0.077 | −0.338 | −0.116 | 1.000 | ||||

| (11) FAMILYFIRMS | −0.076 | −0.073 | −0.298 | −0.212 | 0.291 | 0.291 | −0.413 | −0.446 | −0.352 | 0.161 | 1.000 | |||

| (12) %SHARES | 0.210 | −0.105 | −0.032 | −0.081 | 0.076 | 0.076 | −0.081 | −0.082 | −0.100 | −0.097 | −0.132 | 1.000 | ||

| (13) FAMILY_POWER | 0.080 | −0.085 | −0.314 | −0.223 | 0.254 | 0.254 | −0.452 | −0.455 | −0.344 | 0.071 | 0.914 | 0.134 | 1.000 | |

| (14) FAMILY_BOARD | 0.090 | 0.008 | −0.191 | −0.089 | 0.080 | 0.080 | −0.322 | −0.290 | −0.248 | 0.071 | 0.830 | −0.107 | 0.760 | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | ROA | FALCON | CRIF | VADIS | |

| SIZE | −0.612 | −6.223 *** | −0.887 *** | −78.006 *** | 0.836 *** |

| (4.160) | (1.405) | (0.196) | (19.468) | (0.219) | |

| EQUITY | −1.446 | 3.736 *** | 1.184 *** | 71.808 *** | −0.967 *** |

| (2.685) | (0.847) | (0.118) | (11.783) | (0.136) | |

| EMPLOYEES | 1.559 | 3.132 ** | 0.052 | 28.944 | −0.405 * |

| (4.176) | (1.564) | (0.218) | (21.638) | (0.244) | |

| D/E | −0.873 * | 0.248 | −0.016 | 4.975 ** | −0.016 |

| (0.484) | (0.170) | (0.024) | (2.359) | (0.027) | |

| FAMILY_FIRMS | −46.264 *** | 0.270 | −0.021 | −57.822 | 2.092 *** |

| (13.917) | (4.972) | (0.692) | (68.797) | (0.771) | |

| %SHARES | 0.018 | 0.057 | 0.009 * | −0.035 | 0.005 |

| (0.106) | (0.037) | (0.005) | (0.513) | (0.006) | |

| FAMILY_POWER | 0.321 ** | −0.046 | −0.003 | 0.306 | −0.012 |

| (0.147) | (0.053) | (0.007) | (0.739) | (0.008) | |

| FAMILY_BOARD | 23.000 *** | 4.680 * | 0.284 | 44.284 | −1.067 ** |

| (6.957) | (2.578) | (0.358) | (35.646) | (0.430) | |

| _cons | 22.193 | 14.703 * | 2.274 ** | 670.888 *** | 4.393 *** |

| (22.597) | (8.083) | (1.125) | (111.859) | (1.252) | |

| R-squared | 0.205 | 0.201 | 0.658 | 0.311 | 0.518 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S.; D'Addario, F. The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Assessment in the Tourism Sector. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010008

Leopizzi R, Pizzi S, D'Addario F. The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Assessment in the Tourism Sector. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeopizzi, Rossella, Simone Pizzi, and Fabrizio D'Addario. 2021. "The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Assessment in the Tourism Sector" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010008

APA StyleLeopizzi, R., Pizzi, S., & D'Addario, F. (2021). The Relationship among Family Business, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance: An Empirical Assessment in the Tourism Sector. Administrative Sciences, 11(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11010008