Abstract

It is well-known that entrepreneurs lead extremely busy lives. While research literature reports the stressors of entrepreneurial careers, few empirical studies have examined the actual management of the demands that entrepreneurs face in their daily lives. In this paper, we conducted a study of 472 small business owners and tested hypotheses on the roles of three self-management practices—exercise, work overload, and attention to detail—on stress, security, and job satisfaction. Exercise, work overload, and attention to detail serve as three important self-management practices that are largely under the decision-making of the individual entrepreneur.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurs carry many responsibilities and stressors in the daily operation of their businesses. The success of a venture rests firmly on their shoulders. Research that examines practices that influence the psychological states of entrepreneurs in running their businesses may shed light on how to better cope with this situation. In this paper, we propose the study of self-management practices as they impact entrepreneurial stress, security, and job satisfaction. To address this issue, we conducted a study of 472 small business owners and tested hypotheses on the roles of exercise, work overload, and attention to detail on stress, security, and job satisfaction. Advertisements, magazine articles, and television shows trumpet the benefits of exercise and encourage people to undertake a fitness regimen. Indeed, it would make sense that an exercise program may lead to a less stressful and more productive life for the entrepreneur. However, busy schedules and the challenge of maintaining a fitness regimen lead many people to quit these programs soon after starting them and to return to their more sedentary lifestyles. This paper empirically examines whether spending time away from the business exercising is time well spent. Another decision that entrepreneurs face is the amount of workload they choose to accept in their daily schedule. Many entrepreneurs experience work overload as they decide to place increasing priority on their businesses in their lives. This paper empirically examines whether work overload increases stress, reduces security, and decreases job satisfaction. Finally, the paper examines the effect attention to detail has on stress, security, and job satisfaction. We expect that entrepreneurs who have higher attention to detail will better manage an operation in a way that reduces her/his stress, increases her/his perception of venture security, and increases her/his job satisfaction.

Boyd and Gumpert (1983) identified four causes of entrepreneurial stress: (1) loneliness, (2) immersion in business, (3) people problems, and (4) the need to achieve. They note that not all stress is bad, but if it becomes overbearing and unrelenting in a person’s life, it wears down the body’s physical abilities. However, if stress can be kept within constructive bounds, it can increase a person’s efficiency and improve performance. Locke defines job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke 1976, p. 1300). This study adds to the previous literature by examining the role levels of stress can have on the job satisfaction of entrepreneurs. In general, stress can be viewed as a function of discrepancies between a person’s expectations and ability to meet demands. If a person is unable to fulfill role demands, stress occurs. When entrepreneurs’ work demands and expectations exceed their abilities to perform, they are more likely to experience stress. Additionally, initiating and managing a business requires taking significant risk. These risks may be financial, career, family, social, or psychological. Whether an event or circumstance is considered to be stressful is largely dependent on the perception of each person. Fortunately, coping processes can help the entrepreneur to better handle potentially stressful situations (Bolger 1990; Neck and Cooper 2000; Lupinacci et al. 1993; Cooper 1995; Brandon and Loftin 1991). Self-management constitutes a broad range of coping mechanisms and practices, hence why we utilized three independent variables that we believe entrepreneurs can manage for decreasing stress, increasing a sense of security, and increasing job satisfaction.

Self-management practices are consistent with the underlying foundation of self-leadership in which it is based. Specifically, self-leadership consists of specific behavioral and cognitive strategies designed to positively influence personal effectiveness. Self-leadership strategies are typically partitioned into three primary categories, including behavior-focused strategies, natural reward strategies and constructive thought pattern strategies (Neck et al. 2019; Neck and Houghton 2006). Behavior-focused strategies attempt to increase an individual’s self-awareness in order to facilitate behavioral management, especially the management of behaviors related to necessary but unpleasant tasks (Neck and Houghton 2006). Natural reward strategies are designed to foster situations in which a person is motivated or rewarded by inherently enjoyable aspects of the task or activity (Neck and Houghton 2006. Constructive thought pattern strategies are designed to facilitate the formation of constructive thought patterns (habitual ways of thinking) that can impact performance in a positive manner (Neck and Houghton 2006). Constructive thought pattern strategies include identifying and replacing dysfunctional beliefs and assumptions, mental imagery and positive self-talk (Neck et al. 2019). In the following sections, we explore three specific behaviors—self-management practices—that can improve the subjective experience of entrepreneurial work.

2. Self-Management Practices

Autonomy is an aspect of entrepreneurship that runs through its core (Shir et al. 2019), given its nature of being a self-organized (Shir 2015) and goal-directed pursuit (Bird 1988; Frese 2009; McMullen and Shepherd 2006; Shir et al. 2019). As such, self-management—or the process of managing oneself—has been suggested as a process helpful to entrepreneurial success (D’Intino et al. 2007; Goldsby et al. 2006; Neck et al. 1999; Neck et al. 2013). Self-management is a foundation of self-leadership, and the distinction between these two concepts is expanded upon elsewhere (Manz 1986). Manz and Sims (1980) established the self-management construct as based on the methods of self-observation, self-goal setting, incentive modification, and rehearsal. Essentially, people practicing effective self-management are aware and deliberate about how they utilize their personal resources of time, energy, and attention. For the purposes of this paper, we concentrate on work overload, attention to detail, and exercise as three important self-management practices that are largely subject to the decision-making of the individual entrepreneur. We next examine the role of each of these practices in our proposed model.

2.1. Work Overload

Work overload is the degree to which the “job performance required in a job is excessive or overload due to performance required on a job” (Iverson and Maguire 2000) and is a major contributor to work stress (DeFrank and Ivancevich 1998; Sparks and Cooper 1999; Taylor et al. 1997). As stated earlier, the amount of work an entrepreneur decides to pursue is an important aspect of an entrepreneurial career (Sardeshmukh et al. 2020). Given the expectations of meeting the business and personal demands of owning and operating a business, entrepreneurs may believe they have too much to do or experience a lack of control in managing all the responsibilities. Kuratko (2018) refers to this situation as the “one man band syndrome”, recalling the traveling performers who played multiple instruments at once in putting on a show. We posit that entrepreneurs who endure work overload will experience greater stress in their work and thus offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (1a).

Work overload will be positively related to stress for entrepreneurs.

Additionally, entrepreneurs who work in excess of what seems reasonable to them may question how long they can continue operating the business. For the entrepreneur, the business is their job, so ending the venture essentially brings unemployment to them. In the organizational behavior literature, security addresses “the fear that employees may lose their job and become unemployed” (De Witte 1999, p. 156). It would seem reasonable that entrepreneurs who experience work overload would also endure a lack of security in relying on the future of their venture. Entrepreneurs perceiving their work situations as this leads us to offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (1b).

Work overload will be negatively related to feelings of security for entrepreneurs.

2.2. Attention to Detail

Given that entrepreneurs are ultimately responsible for the success of the business, we would expect many to immerse themselves in the small details of the daily operations as well as the strategic decisions that must be made in the long run. However, psychology research has found that sustained periods of concentration and perseverance can lead to higher stress, anxiety, depression, and hostility (Zuckerman and Lubin 1985; Motowidlo et al. 1986). Yet, we contend that given the nature of entrepreneurial work, attention to detail is important to reduce stress.

Consider small businesses you may have visited that seem orderly and well-run versus ones that have disorganization and inconsistent and haphazard customer service. Now think of the entrepreneurs running the operations. Were there differences in their countenance and the way the business operated? Our study contends that there is a relationship between the way an entrepreneur routinizes manageable details and takes more control of their perceived work. Ambiguity and uncertainty are very challenging aspects of entrepreneurship (Rigotti et al. 2011; Koudstaal et al. 2016). Reducing ambiguity and uncertainty requires attention to detail, enabling the entrepreneur to attend to and prevent negative circumstances that could damage the business. Although not all aspects of a venture can by systematized, organizing and controlling what can be affords an entrepreneur better ability to address unique situations as they occur. Stabilization strategies have been found in psychological research studies to reduce stress, improve circadian rhythms and sleep, and better handle conflicts and crises as they occur (Frank et al. 2000). We posit that entrepreneurs who examine, understand, and manage the working components of their businesses in great detail will have better psychological states. Therefore, we offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (2a).

Attention to detail will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 2 (2b).

Attention to detail will be positively related to feelings of security for entrepreneurs.

2.3. Exercise

Well-being is increasingly appearing as a subject of study in entrepreneurship research (Hmieleski and Sheppard 2019; Stephan 2018; Wiklund et al. 2019). The Gallup Organization has extensively studied well-being and defined it as “the combination of our love for what we do each day, the quality of our relationships, the security of our finances, the vibrancy of our physical health, and the pride we take in what we have contributed to our communities” (Rath et al. 2010, p. 4). Exercise is an important component of physical well-being. Rath et al. (2010) discovered that the benefits of exercise increase with its frequency. Yet, all exercise is not the same. Public health research suggests that intense exercise holds substantial health benefits not found in more relaxed physical activities (Warren and Perlroth 2001; Meltzer and Jena 2010). Given the demanding nature of entrepreneurial work, we sought to discover whether more intensive exercise was related to less stress for entrepreneurs. A consistent physical regimen is a major commitment by an entrepreneur because time spent exercising is also time away from the business (Goldsby et al. 2005; Goldsby et al. 2019). We contend, however, that the self-management practice of frequent intense exercise is worthwhile for entrepreneurs. We, therefore, offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (3a).

Exercise intensity will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 3 (3b).

Exercise intensity will be positively related to feelings of security.

3. Entrepreneurial Psychological States

Many entrepreneurs lead stressful lives due to “hard work, long hours, emotional energy, height, end job stress, role ambiguity, and above all, risk (Buttner 1992; Eden 1975; Kaufmann and Dant 1999; Lewin-Epstein and Yuchtman-Yaar 1991; Min 1990; Bradley and Roberts 2004, p. 39). Despite the stressful components of self-employment, entrepreneurs often continue working long hours for financial gain in spite of the costs to their personal health (Cardon and Patel 2015). However, financial gain is only one important outcome in the life of an entrepreneur. In this paper, we examine job satisfaction as the outcome of study as it relates to the choices that entrepreneurs make regarding daily practices in their life and work. Specifically, we study whether the discretionary choices of workload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity influence stress and security and in turn job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is a long-studied subject in human resource management, organizational behavior, and general management. Hoppock (1935) summarized job satisfaction as a holistic indicator of psychological, physiological, and environmental circumstances that “cause a person truthfully to say I am satisfied with my job” (Aziri 2011, p. 77). As such, job satisfaction has been studied as an internal state, or attitude, about a person’s overall view of the work they are presently doing (Vroom 1964; Locke 1976; Mullins and Christy 2005; Armstrong 2006). Job satisfaction has been extensively studied in larger organizations, including its relationship to corporate entrepreneurial activity (Adonisi 2005; Holt et al. 2007; Adonisi and Van Wyk 2012); however, a gap exists in the job satisfaction literature regarding self-employment.

Levels of stress, security, and job satisfaction are conditions experienced by entrepreneurs; the former to be reduced if possible and the latter two to be enhanced. Locke defines job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke 1976). It is an important component of mental health and work–life balance. Therefore, we concentrate on stress, security, and job satisfaction as three indicators of psychological well-being for the individual entrepreneur. We next examine the role of each of these psychological states in our proposed model.

3.1. Security

Security is something most entrepreneurs give up when going out on their own (Morris and Lewis 1991). Therefore, it would be a prized condition when it manifests. Work situations in which security is perceived as often in jeopardy can incur mental and physical harm over time (Kornhauser 1965; Beehr and Newman 1978; Frese 1985; Ivancevich 1986; Ivancevich and Matteson 1980; Warr 1987; Weitz 1970). More specifically, Porter and Jick (1980) discovered that increased job insecurity can incur extreme psychosomatic conditions such as depression, anxiety, and irritation. Much of the seminal work on job security and quality of life examines the relationship on blue-collar workers, since much of their employment status is out of their hands. However, entrepreneurs may experience similar conditions of insecurity in their work. Entrepreneurs often choose to own and manage their own enterprises for autonomy reasons, removing stressors of working for someone else. Yet, the responsibilities that would have been carried by a “boss” are now firmly on the shoulders of the entrepreneur. We contend that entrepreneurs who operate with high levels of insecurity in their enterprise will bear significant mental costs; however, entrepreneurs who can increase their sense of security in their work will experience less stress. We, therefore, offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Security will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs.

Herzberg (2003) described job security as the expectation an employee has of stability in their employment status. Beyond the health factors previously discussed in this paper, security impacts attitudes toward organizational factors, such as employee turnover (Arnold and Feldman 1982), employee retention (Ashford et al. 1989; Bhuian and Islam 1996; Iverson and Roy 1994), and organizational commitment (Abegglen 1958; Ashford et al. 1989; Bhuian and Islam 1996; Iverson 1996; Morris et al. 1993). These three important organizational variables have a significant effect on the sustainable performance of a company. A company with employees committed to their work and staying employed with the organization is more likely to perform better than one having to devote major resources to the endless recruiting, selection, and training that comes with high turnover. In turn, job satisfaction has been a variable of study in much of these variables. As Imran et al. (2015, p. 841) state, “Job satisfaction comes when an employee is rewarded well and is provided with those job tasks that are challenging yet interesting.” Rewarding work is an important consideration for staying with an organization. In a related manner, entrepreneurial exit is a topic gaining interest in the entrepreneurship literature (DeTienne and Cardon 2012; Sardeshmukh et al. 2020). When entrepreneurs decide to leave their organization, that often means shutting down the enterprise. In particular, motivational drivers of exit, many of which are not tied to financial performance, are gaining prominence in the research literature (DeTienne 2010; DeTienne and Cardon 2012; Wennberg et al. 2010; Wennberg and DeTienne 2014; Sardeshmukh et al. 2020). Research that supports insights into lessening entrepreneurial exit would prove useful for increasing economic vitality in a community. In this article, we have placed our attention on job satisfaction as an important outcome for study in improving entrepreneurial work.

Given that security has been found to be of significance in studies of job satisfaction with company employees, we would expect entrepreneurs would also experience more satisfaction in their work when they feel secure about their situations. We, therefore, offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5

Feelings of security will be positively related to job satisfaction.

3.2. Stress

Our model proposes a central role for stress in the work experience of the entrepreneur. Indeed, based on the logic of the preceding hypotheses, we believe that the strength of the relationships between stress and its independent variables (work overload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity: Hypothesis 1a, Hypothesis 2a, and Hypothesis 3a) and its dependent variable, job satisfaction, will be such that stress will be a significant mediating variable. Therefore, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6

Stress will mediate the relationships between the independent variables (work overload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity) and job satisfaction for entrepreneurs.

4. Method

Participants: 542 entrepreneurs located in the Midwest (Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky) were surveyed for this study, of which 472 were completed. Of these, the average age was 47 years and 79% were male. Nineteen percent had finished high school, 29% had attended college, 40% had completed college, and 12% held graduate degrees. A wide variety of small businesses were represented.

Measures: In constructing this study to examine exercise, we recognized that not all exercise is alike. An exercise intensity score was then generated by multiplying the intensity category by the frequency of the activity by the length of the session. This approach has been widely used in medical studies such as measuring level of alcoholism, drug use, and other health-related habits. The underlying premise is to assess the nature of activity, how frequently it occurs, and for how long does it occur at each frequency unit.

Exercise intensity was measured by the following formula:

Exercise is the intensity category of the exercise on a scale from 1 to 7 where 1 is the least vigorous and 7 is the most vigorous; Frequency is the number of days per week an exercise session of performed; Session Length is the duration of the exercise per session. This technique recognizes that not all exercise is alike, and it has been widely used in medical studies such as measuring level of alcoholism, drug use, and other health-related habits. The underlying premise is to assess the nature of activity, how frequently it occurs, and for how long does it occur at each frequency unit. Simply asking respondents how much they exercise induces much interpretation and variability in comprehension of the items. Thus, the exercise intensity measure attempts to better define for respondents what is being asked, as well as improve the scoring for the researchers. For example, a person who works out in a higher category of exertion exercise every day for an hour (such as a competitive runner) will score higher exercise intensity than a person who walks each morning for twenty minutes. However, if respondents were simply asked, “How often do you exercise?”, this degree of differentiation would not be captured in the results. Therefore, the results in this study capture the degree of effort, the frequency, and length of average session. In addition, note that the sigma sign at the front of the equation addresses that many respondents may participate in numerous activities. Therefore, we attempted to measure exercise intensity with a more holistic approach that captures the range of possibilities of exercise activity by the respondents.

The study utilized two new scales to measure work overload and attention to detail. To operationalize stress, we used the daily hassles measure developed by (Holm and Holroyd 1992). Job satisfaction was measured by 7 items on a five-point scale (1—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree) adapted from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire and modified for the small business owner or general manager. Work overload and attention to detail were measured by 4-item and 5-item scales, respectively, that were developed for this study. Stress was measured by a 5-item scale from X (Holm and Holroyd 1992). Job satisfaction and security were measured by 3-item and 2-item scales, respectively, adapted from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al. 1967) to apply to the small business owner or general manager. All scales were measured on 5-point scales (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Data for the analysis were collected from 472 entrepreneurs located in the Midwest (Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky). Data for the analysis were selected randomly from Chambers of Commerce directories. Small business owners were interviewed by the authors using a structured interview format that resulted in a questionnaire being returned for each firm. The owners were contacted by phone and were advised that the study was part of an ongoing university effort to study entrepreneurs. They then were asked to participate, and an interview time was established. Only a few of the owners contacted refused to be interviewed. Those who chose not to participate typically gave reasons such as they were too busy, or they never participate in surveys. This data collection procedure has been used in similar studies of entrepreneurial firms (McEvoy 1984; Hornsby and Kuratko 1990; Lyles et al. 1993; Kuratko et al. 1997).

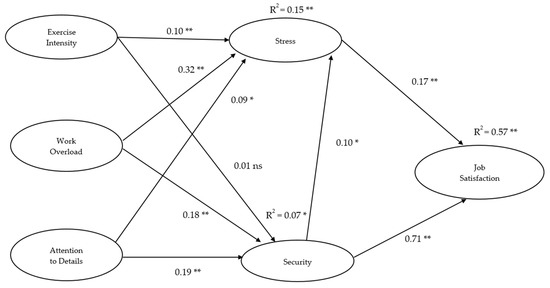

A structural equation model was created to test the hypotheses. Hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a test the relationships between work overload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity and stress. Hypotheses 1b, 2b, and 3b test the relationships between work overload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity and security. Hypothesis 4 tests the relationship between security and stress. Hypothesis 5 tests the relationship between security and job satisfaction. Hypothesis 6 tests whether stress mediates work overload, attention to detail, exercise intensity, and security and job satisfaction.

5. Results

Self-management, a foundational concept of self-leadership, is a broad range of coping mechanisms and practices, and is thus why we utilized three independent variables that we believe entrepreneurs can manage for decreasing stress and increasing job satisfaction. Support for the hypotheses were determined by the significance or non-significance of the associated paths in the structural equation model. Based upon the criterion, Hypotheses 1a, 2a, 3a, Hypotheses 2b, 3b, Hypotheses 4, Hypothesis 5, and Hypothesis 6 were supported by the data. The hypothesized structural equation model fit the data well (Χ2 = 367.6; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.050; non-normed fit index (NNFI) = 0.96; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.042), and tested better than alternative models. The exogenous variables in this model are within the self-management theme. In short, we maintain that the self-management variables lead to both security and stress, enhancing the former and attenuating the latter. Security and stress, in turn, enhance and attenuate job satisfaction, respectfully.

More specifically, Hypothesis 1a stated that work overload will be positively related to stress for entrepreneurs and was supported by the data (γ = −0.10, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 1b stated that work overload will be negatively related to feelings of security for entrepreneurs and was supported (γ = −0.18, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2a stated that attention to detail will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs and was supported (γ = −0.09, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 2b stated that attention to detail will be positively related to feelings of security for entrepreneurs and was supported (γ = 0.19, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 3a stated that exercise intensity will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs and was supported (γ = −0.10, p < 0.01), but Hypothesis 3b stated that exercise intensity will be positively related to feelings of security and was not supported (γ = −0.01, ns). Perhaps physical fitness is detached from the operations of the business itself, but it does appear to reduce the stress levels that an entrepreneur experiences. It would seem warranted then for an entrepreneur to participate in intensive exercise to reduce stress, which also improves job satisfaction with owning and running a business. Hypothesis 4 stated that security will be negatively related to stress for entrepreneurs and was supported (γ = −0.10, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 5 stated that feelings of security will be positively related to job satisfaction and was supported (γ = 0.71, p < 0.01). In addition, Hypothesis 6 stated that stress will mediate the relationships between the independent variables (work overload, attention to detail, and exercise intensity) and job satisfaction for entrepreneurs. The mediation was supported by the data (R2 = 0.15, p < 0.01).

Thus, we conclude that the findings suggest that overall the self-management practices of minimizing work overload, increasing attention to detail, and maintaining high levels of exercise intensity are beneficial to an entrepreneur by reducing stress, increasing security, and increasing job satisfaction.

Prior to testing our hypotheses, we subjected the 20 items that measured our variables to a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The measurement model fit the data well: χ2 = 366.4, df = 156; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.051; non-normed fit index (NNFI) = 0.96, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.042. The items and their factor loadings appear in Table 1. All scales produced acceptable internal reliabilities. Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations, correlations, and internal reliabilities (coefficient alphas) for the variables.

Table 1.

Survey items and confirmatory factor loadings.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities for survey items (n = 329).

Though conceptually distinct, the variables, job satisfaction and security, could both be thought of as satisfaction variables. (They both came from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire.) Consequently, we felt it prudent to test whether our instrument could distinguish between them. To test this, we estimated a competing model with the job satisfaction and the security items loading on the same latent variable; that is, a more restrictive model. We then invoked the chi-square difference test, as per Bollen (1989). A more restrictive model, i.e., with more degrees of freedom, will always fit worse than a less restrictive model. If the (more restrictive model) competing model’s fit is not significantly worse than the (less restrictive model) hypothesized model, then the competing model will be preferred due to its increased parsimony. On the other hand, if the competing model’s fit is significantly worse than the hypothesized model, then the hypothesized model will be preferred due to its superior explanatory property. Our hypothesized model was preferred (Δχ2 = 115.8, df = 5, p < 0.001) demonstrating that our instrument was able to distinguish between job satisfaction and security.

To test our hypotheses, we estimated the structural equation model shown in Figure 1. It also fit the data well: χ2 = 367.6, df = 159; RMSEA = 0.050; NNFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.042. All the paths representing the hypotheses were significant, so all hypotheses were supported.

Figure 1.

Standardized path coefficients. χ2 = 367.6, df = 159; RMSEA = 0.050; NNFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.042. * is p ≤ 0.05, ** is p ≤ 0.01, ns + nonsignificant p > 0.05.

6. Discussion and Implications

Entrepreneurship is one of most challenging but potentially satisfying pursuits in business. Yet little research has examined the job satisfaction that comes with owning and running a business. The results in this paper conclude that stress plays a significant role in the satisfaction entrepreneurs find in their line of work. More importantly as a contribution to the self-leadership-related research literature, our findings also suggest that positive self-management practices can reduce the stress levels of entrepreneurs, in turn increasing job satisfaction. Specifically, avoiding work overload, paying attention to the details of running the business, and committing to a fitness regimen based on intensive exercise are helpful self-management practices for entrepreneurs. All three practices come with an important decision of whether to pursue them. Successful businesses require significant commitment in time, attention, and energy. In a career where there may never seem to be enough time in a day to finish what is intended, entrepreneurs may find themselves overworked. However, doing so is likely to lead to increased stress. Our research finds intensive exercise as one activity away from work that is a good use of that time, especially in reducing stress. Yet, when the entrepreneur is involved in the business paying attention to detail is another self-management practice that should be honed. Ensuring that the small matters are handled well in the daily operations helps to prevent problems that may grow into more stressful issues, which also give an entrepreneur a better of sense of security in their enterprise’s future.

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. First, the size and regional characteristics of the study limit its generalizability. Further studies in different regions of the United States, as well as globally, would allow more substantive conclusions than what our findings suggest. Second, the study is cross-sectional. Future longitudinal research would be warranted with self-management training on attention to detail, exercise intensity, and work overload with pre- and post-tests on stress, security, and job satisfaction to more conclusively validate our model. Third, this study focused on behaviors with regard to self-management practices and entrepreneurship. Extending this research to include the cognitive and environmental aspects of self-leadership would offer deeper insight into the psychological states of entrepreneurs and their work. However, we believe the significant findings in this study indicate that further research, as described above, is warranted.

In conclusion, we advise entrepreneurs to follow the advice of scholars in the self-management and self-leadership literature. At the same time, we hope this paper provides impetus for more scholars to follow up that line of research in entrepreneurship with more empirical studies of the benefits, as well as challenges, of applying self-management in entrepreneurial pursuits. While the findings in this paper suggest that self-management practices can improve the subjective experience entrepreneurs have in running their businesses, treatment studies would shed more light on the phenomenon. For example, surveying entrepreneurs on stress, security, and job satisfaction pre-test, then conducting workshops on intensive exercise, time management and scheduling (work overload), and perhaps mindfulness (attention to detail), and then returning to survey the post-test results on stress, security, and job satisfaction would be one such possible approach. Additionally, while this paper examined self-management behaviors of entrepreneurs, cognitive strategies would be another interesting line of research that scholars could pursue as well. Given the success of such approaches with self-management with traditional organizational managers, we believe more research is warranted to study the improvement that entrepreneurs can have in their work as well.

Author Contributions

All authors participated equally in the following aspects of the paper: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The researchers secured approval for the project from Ball State University’s Internal Review Board (IRB).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to authors preference.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abegglen, James C. 1958. Personality factors in social mobility: A study of occupationally mobile businessmen. Genetic Psychology Monographs 58: 101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adonisi, Mandla. 2005. Antecedents of an organizational culture that fosters corporate entrepreneurship. People Dynamics 23: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Adonisi, Mandla, and Rene Van Wyk. 2012. The influence of market orientation, flexibility and job satisfaction on corporate entrepreneurship. International Business & Economics Research Journal 2011: 477–86. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Michael A. 2006. Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice. London: Kogan Page Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Hugh J., and Daniel C. Feldman. 1982. A multivariate analysis of the determinants of job turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 67: 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, Susan J., Cynthia Lee, and Philip Bobko. 1989. Content, cause, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal 32: 803–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aziri, Brikend. 2011. Job satisfaction: A literature review. Management Research & Practice 3: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr, Terry A., and John E. Newman. 1978. Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: A facet analysis, model, and literature review. Personnel Psychology 31: 665–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuian, Shahid N., and Muhammad S. Islam. 1996. Continuance commitment and extrinsic job satisfaction among a novel multicultural expatriate workforce. The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business 32: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, Barbara. 1988. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review 13: 442–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, Niall. 1990. Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, Kenneth A. 1989. Structural Equation Modeling with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, David P., and David E. Gumpert. 1983. Coping with entrepreneurial stress. Harvard Business Review 61: 44. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Don E., and James A. Roberts. 2004. Self-employment and job satisfaction: Investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. Journal of Small Business Management 42: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, Jeffrey E., and J. Mark Loftin. 1991. Relationship of fitness to depression, state and trait anxiety, internal health locus of control, and self-control. Perceptual and Motor Skills 73: 563–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttner, E. Holly. 1992. Entrepreneurial stress: Is it hazardous to your health? Journal of Managerial Issues 4: 223–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, Melissa S., and Pankaj C. Patel. 2015. Is stress worth it? Stress-related health and wealth trade-offs for entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology 64: 379–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Kenneth H. 1995. It’s Better to Believe. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- D’Intino, Robert S., Michael G. Goldsby, Jeffery D. Houghton, and Chris P. Neck. 2007. Self-leadership: A process for entrepreneurial success. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 13: 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, Hans. 1999. Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8: 155–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFrank, Richard S., and John Ivancevich. 1998. Stress on the Job: An Executive Update. The Academy of Management Executive 12: 55–66. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4165477 (accessed on 24 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, Dawn R. 2010. Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, Dawn R., and Melissa S. Cardon. 2012. Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics 38: 351–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, Dov. 1975. Organizational membership vs. self-employment: Another blow to the American dream. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 13: 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Ellen, Holly A. Swartz, and David J. Kupfer. 2000. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: Managing the chaos of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 48: 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, Michael. 1985. Stress at work and psychosomatic complaints: A causal interpretation. Journal of Applied Psychology 70: 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, Michael. 2009. Toward a Psychology of Entrepreneurship: An Action Theory Perspective. Delft: Now Publishers Inc., vol. 5, pp. 435–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, Michael G., Donald F. Kuratko, and James T. Bishop. 2005. Entrepreneurship and fitness: An examination of rigorous exercise and goal attainment among small business owners. Journal of Small Business Management 43: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsby, Michael G., Donald F. Kuratko, Jeffery S. Hornsby, Jeffrey D. Houghton, and Chris P. Neck. 2006. Social cognition and corporate entrepreneurship: A framework for enhancing the role of middle-level managers. International Journal of Leadership Studies 2: 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsby, Michael G., Donald F. Kuratko, and Chris P. Neck. 2019. An examination of the effect of exercise on stress and satisfaction for entrepreneurs. Journal of Leadership and Management 1: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, Frederick. 2003. One more time: How do you motivate employees. Harvard Business Review 81: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, Keith M., and Leah D. Sheppard. 2019. The Yin and Yang of entrepreneurship: Gender differences in the importance of communal and agentic characteristics for entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being and performance. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 709–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Jeffrey E., and Kenneth A. Holroyd. 1992. The Daily Hassles Scale (Revised): Does it measure stress or symptoms? Behavioral Assessment 14: 465–82. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Daniel T., Matthew W. Rutherford, and Gretchen R. Clohessy. 2007. Corporate entrepreneurship: An empirical look at individual characteristics, context, and process. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 13: 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppock, Robert. 1935. Job Satisfaction. New York: Harper and Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby, Jeffrey S., and Donald F. Kuratko. 1990. Human resource management in small business: Critical issues for the 1990s. Journal of Small Business Management 28: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, Rabia, Mehwish Majeed, and Abida Ayub. 2015. Impact of organizational justice, job security and job satisfaction on organizational productivity. Journal of Economics, Business and Management 3: 840–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancevich, John M. 1986. Life events and hassles as predictors of health symptoms, job performance, and absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior 7: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancevich, John M., and Michael T. Matteson. 1980. Stress and Work: A Managerial Perspective. Glenview: Scott Foresman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, Roderick D. 1996. Employee acceptance of organizational change: The role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management 7: 122–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, Roderick, and Catherine Maguire. 2000. The relationship between job and life satisfaction: Evidence from a remote mining community. Human Relations 53: 807–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, Roderick D., and Parimal Roy. 1994. A causal model of behavioral commitment: Evidence from a study of Australian blue-collar employees. Journal of Management 20: 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Patrick J., and Rajiv P. Dant. 1999. Franchising and the domain of entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing 14: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhauser, Arthur. 1965. Mental Health of the Industrial Worker: A Detroit Study. New York: John Willey & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Koudstaal, Martin, Randolph Sloof, and Mirjam Van Praag. 2016. Risk, uncertainty, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a lab-in-the-field experiment. Management Science 62: 2897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D. F. 2018. Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, and Practice. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kuratko, Donald F., Jeffrey S. Hornsby, and Douglas W. Naffziger. 1997. An examination of owner’s goals in sustaining entrepreneurs hip. Journal of Small Business Management 35: 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-Epstein, N., and E. Yuchtman-Yaar. 1991. Health risks of self-employment. Work and Occupations 18: 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Edward. A. 1976. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1: 1297–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lupinacci, Norwood S., Roberta E. Rikli, C. Jessie Jones, and Diane Ross. 1993. Age and physical activity effects on reaction time and digit symbol substitution performance in cognitively active adults. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 64: 144–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyles, Majorie A., Jnga. S. Baird, J. Burdeane Orris, and Donald F. Kuratko. 1993. Formalized planning in small business: Increasing strategic choices. Journal of Small Business Management 31: 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Manz, C. C. 1986. Self-leadership: Toward and Expanded Theory of Self-Influence processes in organizations. Academy of Management Review 11: 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, Charles C., and Henry P. Sims, Jr. 1980. Self-management as a substitute for leadership: A Social Learning Theory perspective. Academy of Management Review 5: 361–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, Glenn M. 1984. Small business personnel practices. Journal of Small Business Management 22: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, Jeffrey S., and Dean A. Shepherd. 2006. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review 31: 132–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, David O., and Anupam B. Jena. 2010. The economics of intense exercise. Journal of Health Economics 29: 347–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Pyong Gap. 1990. Problems of Korean immigrant entrepreneurs. International Migration Review 24: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Michael H., and Pamela S. Lewis. 1991. Entrepreneurship as a significant factor in societal quality of life. Journal of Business Research 23: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Tim, Helen Lydka, and Mark Fenton O’Creevy. 1993. Can commitment be managed? A longitudinal analysis of employee commitment and human resource policies. Human Resource Management Journal 3: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motowidlo, Stephen J., John S. Packard, and Michael R. Manning. 1986. Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, Laurie J., and Gill Christy. 2005. Management and Organisational Behaviour. London: Harlow, Financial Times Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Neck, Chris P., and K. H. Cooper. 2000. The fit executive: Exercise and diet guidelines for enhancing performance. Academy of Management Perspectives 14: 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Christopher, and Jeffery Houghton. 2006. Two Decades of Self-Leadership Theory and Research: Past Developments, Present Trends, and Future Possibilities. Journal of Managerial Psychology 21: 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Chris P., H. M. Neck, Charles C. Manz, and Jeffrey Godwin. 1999. I think I can; I think I can. Journal of Managerial Psychology 14: 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Chris P., Jeffery D. Houghton, Shruti R. Sardeshmukh, Michael G. Goldsby, and Jeffrey L. Godwin. 2013. Self-leadership: A cognitive resource for entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 26: 463–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, Christopher, Charles Manz, and Jeffery Houghton. 2019. Self-Leadership: The Definitive Guide To Personal Excellence, 2nd ed. New York: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Jane, and Hershel Jick. 1980. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. New England Journal Medicine 302: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, Tom, Jim K. Harter, and Jim Harter. 2010. Wellbeing: The Five Essential Elements. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti, Luca, Matthew Ryan, and Rhema Vaithianathan. 2011. Optimism and firm formation. Economic Theory 46: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, Shruti R., Michael G. Goldsby, and Ronda M. Smith. 2020. Are work stressors and emotional exhaustion driving exit intentions among business owners? Journal of Small Business Management 2020: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shir, Nadav. 2015. Entrepreneurial well-being: The payoff structure of business creation. Stockholm: Stockholm School of Economics, p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Shir, Nadav, Boris N. Nikolaev, and Joakim Wincent. 2019. Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, Kate, and Carly L. Cooper. 1999. Occupational differences in the work–strain relationship: Towards the use of situation-specific models. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 72: 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Ute. 2018. Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives 32: 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Shelley E., Rene L. Repetti, and Teresa Seeman. 1997. Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology 48: 411–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vroom, Victor H. 1964. Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley, p. 331. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, Peter. 1987. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Michelle P., and N. E. Perlroth. 2001. Hormones and sport-the effects of intense exercise on the female reproductive system. Journal of Endocrinology 170: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, David J., Rene V. Dawis, George W. England, and Lloyd H. Lofquist. 1967. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Industrial Relations Center, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Weitz, J. 1970. Psychological research needs on the problems of human stress. Social and Psychological Factors in Stress 54: 124–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg, Karl, and Dawn R. DeTienne. 2014. What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal 32: 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, Karl, Johan Wiklund, Dawn R. DeTienne, and M. S. Cardon. 2010. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 361–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, Johan, Boris Nikolaev, Nadav Shir, Maw Der Foo, and S. Bradley. 2019. Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 579–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Marvin, and Bernard Lubin. 1985. Manual for the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).