Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art

Abstract

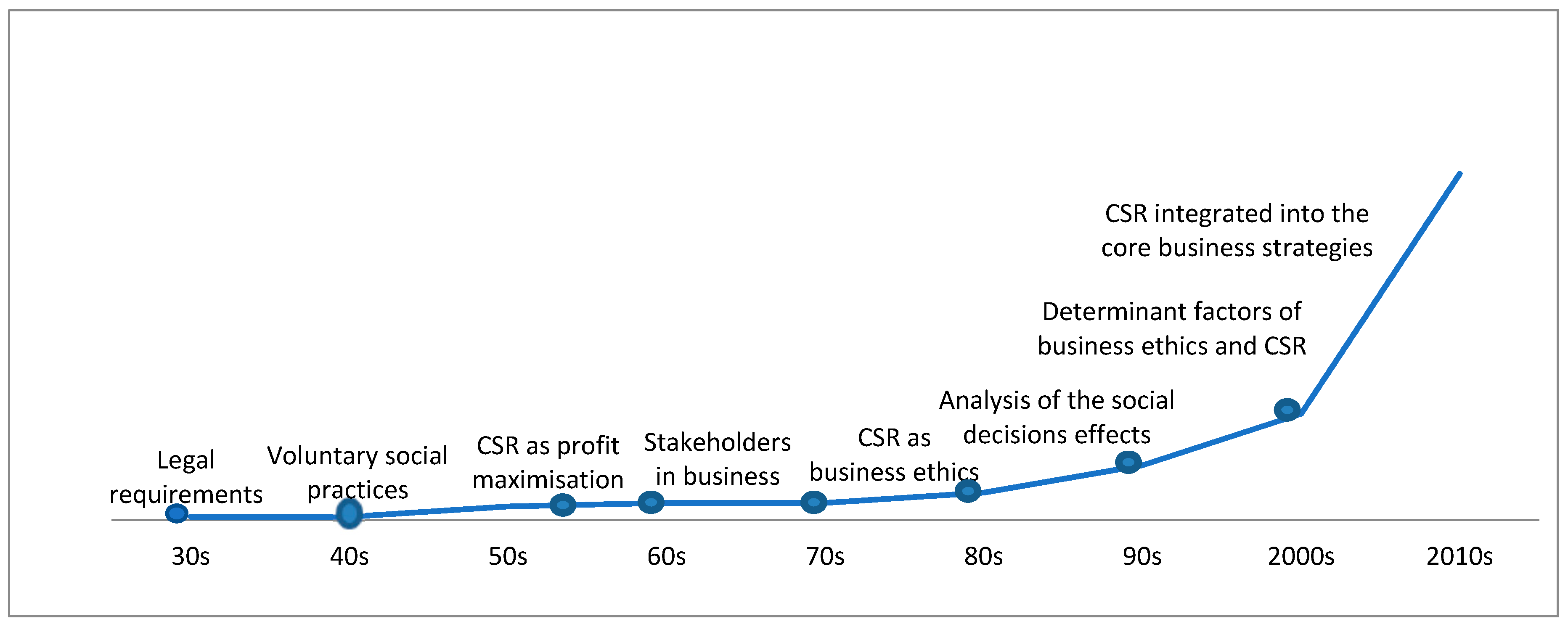

1. The Evolution and Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility

1.1. The Context in Which CSR Takes Place and Its Evolution

1.2. The Development of CSR in the Business World

2. The Objectives and Purposes of Corporate Social Responsibility

3. The Theoretical Framework of Corporate Social Responsibility

4. Method

4.1. Scope of the Review

4.2. Screening Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, Frank W. 1951. Management’s responsibilities in a complex world. Harvard Business Review 29: 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Richard, Sally Jeanrenaud, John Bessant, David Denyer, and Patrick Overy. 2016. Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews 18: 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, Siti. N., and Maimunah Ismail. 2015. Antecedents of philanthropic behavior of health care volunteers. European Journal of Training and Development 39: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin-Chaudhry, Anjum. 2016. Corporate social responsibility-from a mere concept to an expected business practice. Social Responsibility Journal 12: 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, Azlan B., Lim L. Ling, and Yahya Sofri. 2007. A study of corporate philanthropic traits among major Malaysian corporations. Social Responsibility Journal 3: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracil, Elisa. 2019. Corporate social responsibility of Islamic and conventional banks. International Journal of Emerging Markets 14: 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arco-Castro, Lourdes, María Victoria López-Pérez, María del Carmen Pérez-López, and Lázaro Rodríguez-Ariza. 2020. How market value relates to corporate philanthropy and its assurance. The moderating effect of the business sector. Business Ethics: A European Review 29: 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlow, Peter. 1991. Personal characteristics in college students’ evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 10: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, Mehrnaz, Michelle Adams, Tony R. Walker, and Greg Magnan. 2018. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: A theoretical review of their relationships. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 25: 672–82. [Google Scholar]

- Aßländer, Michael S., Julia Roloff, and Dilek Zamantili Nayır. 2016. Suppliers as stewards? Managing social standards in first-and second-tier suppliers. Journal of Business Ethics 139: 661–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, Kenneth E., Archie B. Carroll, and John D. Hatfield. 1985. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal 28: 446–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Seong M., Md. Abdul K. Masud, and John D. Kim. 2018. A cross-country investigation of corporate governance and corporate sustainability disclosure: A signaling theory perspective. Sustainability 10: 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagire, Vicent A., Inmaculate Tusiime, Grace Nalweyiso, and John B. Kakooza. 2011. Contextual environment and stakeholder perception of corporate social responsibility practices in Uganda. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 18: 102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Louis. 1975. The Mission of Our Business Society. Harvard Business Review 53: 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Chester. 1938. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, Henrikke, Frank Boons, and Annica Bragd. 2002. Mapping the green product development field: Engineering, policy and business perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 10: 409–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske-Janssen, Philip, Stefan Schaltegger, and Sonja Liedke. 2019. Performance measurement in sustainable supply chain management: Linking research and practice. In Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 331–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri, Saumitra N., and Ekta Selarka. 2016. Corporate Social Responsibility Around the World: An Overview of Theoretical Framework, and Evolution. In Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility of Indian Companies. Singapore: Springer, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, Nancy, Julian M. Allwood, A. R. Willey, and Henry King. 2011. Development of an eco-ideation tool to identify stepwise greenhouse gas emissions reduction options for consumer goods. Journal of Cleaner Production 19: 1279–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglioli, Elena, Moir Lance, and Véronique Ambrosini. 2006. Developing the wider role of business in society: The experience of Microsoft in developing training and supporting employability. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 6: 401–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslah, Kais, Lawrence Kryzanowski, and Bouchra M’Zali. 2018. Social performance and firm risk: Impact of the financial crisis. Journal of Business Ethics 149: 643–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Howard R. 1953. Social Responsibility of the Businessman. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, Stephen, and Andrew Millington. 2003. The effect of stakeholder preferences, organizational structure and industry type on corporate community involvement. Journal of Business Ethics 45: 213–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Manuel Castelo, and Lúcia Lima Rodrigues. 2006. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics 69: 111–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, Marina, and Valentina Lagasio. 2019. Environmental, social, and governance and company profitability: Are financial intermediaries different? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 576–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brønn, Peggy S., and Deborah Vidaver-Cohen. 2009. Corporate motives for social initiative: Legitimacy, sustainability, or the bottom line? Journal of Business Ethics 87: 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, Jacob, Saim Kashmiri, and Vijai Mahajan. 2017. Signaling virtue: Does firm corporate social performance trajectory moderate the social performance–financial performance relationship? Journal of Business Research 81: 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, John E., Elias Kyriazis, and Gary Noble. 2015. Developing CSR giving as a dynamic capability for salient stakeholder management. Journal of Business Ethics 130: 403–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1991. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons 34: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Archie B. 1999. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society 38: 268–95. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Archie B. 2008. A history of corporate social responsibility: Concepts and practices. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Archie B., and Kareem M. Shabana. 2010. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews 12: 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Ching-Hsun. 2011. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. Journal of Business Ethics 104: 361–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelli, Mohamed, Sylvain Durocher, and Jacques Richard. 2014. France’s new economic regulations: Insights from institutional legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27: 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, Reza H., Sungchul Choi, Simon Ennis, and Dongseop Chung. 2019. Which Dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility is a Value Driver in the Oil and Gas Industry? Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration 36: 260–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closon, Caroline, Christophe Leys, and Catherine Hellemans. 2015. Perceptions of corporate social responsibility, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Management Research: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management 13: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, Philip L., and Robert A. Wood. 1984. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 27: 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, Brian L., Trevis Certo, R. Duane Ireland, and Christopher R. Reutzel. 2011. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. Journal of Management 37: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, Neraline J., James Wallace, and Rana Tassabehji. 2007. An analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Identity and Ethics Teaching in Business School. Journal of Business Ethics 76: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupertino, Sebastiano, Costanza Consolandi, and Alessandro Vercelli. 2019. Corporate social performance, financialization, and real Investment in US manufacturing firms. Sustainability 11: 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, Alexander. 2008. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Keith. 1973. The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal 16: 312–22. [Google Scholar]

- Degie, Bruck, and Wassie Kebede. 2019. Corporate social responsibility and its prospect for community development in Ethiopia. International Social Work 62: 376–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Miras-Rodríguez, María, Amalia Carrasco-Gallego, and Bernabé Escobar-Pérez. 2013. Are socially responsible behaviors paid off equally? A Cross-cultural analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22: 237–56. [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Miras-Rodríguez, María, Amalia Carrasco-Gallego, and Bernabé Escobar-Pérez. 2014. Has the CSR engagement of electrical companies had an effect on their performance? A closer look at the environment. Business Strategy and the Environment 24: 819–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, Prasanta K., Nikolaos Petridis, Konstantinos Petridis, Chrisovalantis Malesios, Jonathan D. Nixon, and Kumar Ghosh. 2018. Environmental management and corporate social responsibility practices of small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production 195: 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Thomas, and Thomas W. Dunfee. 1994. Toward a unified conception of business ethics: Integrative social contracts theory. Academy of Management Review 19: 252–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, Thomas, and Katrin Muff. 2016. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organization & Environment 29: 156–74. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Edwin M. 1976. The social role of business enterprise in Britain: An American perspective: Part I. Journal of Management Studies 13: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Edwin M. 1987. The corporate social policy process: Beyond business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and corporate social responsiveness. California Management Review 29: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guadaño, Josefina, and Jesús H. Sarria-Pedroza. 2018. Impact of corporate social responsibility on value creation from a stakeholder perspective. Sustainability 10: 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Kyla, Jessica Geenen, Marie Jurcevic, Katya McClintock, and Glynn Davis. 2009. Applying asset-based community development as a strategy for CSR: A Canadian perspective on a win–win for stakeholders and SMEs. Business Ethics: A European Review 18: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, Caroline. 2018. Competing for government procurement contracts: The role of corporate social responsibility. Strategic Management Journal 39: 1299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Robert C., and Woodrow D. Richardson. 1994. Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Business Ethics 13: 205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosfuri, Andrea, Marco S. Giarratana, and Esther Roca. 2011. Community-focused strategies. Strategic Organization 9: 222–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, William C. 2016. Commentary corporate social responsibility: Deep roots, flourishing growth, promising future. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic management: Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. B. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Business Ethics Quarterly 4: 409–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1970. A theoretical framework for monetary analysis. Journal of Political Economy 78: 193–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, Isabel, José Manuel Prado-Lorenzo, and Isabel-María García-Sánchez. 2011. Corporate social responsibility and innovation: A resource-based theory. Management Decision 49: 1709–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, Anderson, Luis Mendes, Carla Marques, and Carla Mascarenhas. 2019. Factors influencing students’ corporate social responsibility orientation in higher education. Journal of Cleaner Production 215: 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Yongqiang, and Haibin Yang. 2016. Do employees support corporate philanthropy? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Management and Organization Review 12: 747–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Cristina-Andrea Araújo-Bernardo. 2020. What colour is the corporate social responsibility report? Structural visual rhetoric, impression management strategies, and stakeholder engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1117–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Sanchez, Raquel, María Victoria López-Pérez, and Antonio M. López-Hernández. 2018. Current trends in research on social responsibility in state-owned enterprises: A review of the literature from 2000 to 2017. Sustainability 10: 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, Martin, Nancy M. P. Bocken, and Erik Jan Hultink. 2016. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. Journal of Cleaner Production 135: 1218–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Jordana J., Jie Yan, and Dorothy E. Leidner. 2019. Data philanthropy: Corporate responsibility with strategic value? Information Systems Management 37: 186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, Paul C., Craig B. Merrill, and Jared M. Hansen. 2009. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal 30: 425–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Carrasco, Pablo, Encarna Guillamon-Saorin, and Beatriz Garcia Osma. 2016. The illusion of CSR: Drawing the line between core and supplementary CSR. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 7: 125–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ramos, María I., Mario J. Donate, and Fátima Guadamillas. 2014. Technological posture and corporate social responsibility: Effect on innovation performance. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal 13: 2497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Guerras-Martín, Luis Á., and José E. Navas-López. 2015. La dirección estratégica de la empresa: Teoría y aplicaciones. Pamplona: Thomson Reuters Civitas. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, George, and Antonis Skouloudis. 2018. Corporate social responsibility and innovative capacity: Intersection in a macro-level perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 182: 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Imran, Zahid Riaz, Ghulam A. Arain, and Omer Farooq. 2016. How do internal and external CSR affect employees’ organizational identification? A perspective from the group engagement model. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, Maretno A., and Jim Salas. 2017. Strategic and institutional sustainability: Corporate social responsibility, brand value, and Interbrand listing. Journal of Product & Brand Management 26: 545–58. [Google Scholar]

- Haski-Leventhal, Debbie, and Christine Foot. 2016. The relationship between disclosure and household donations to nonprofit organizations in Australia. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45: 992–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlová, Kristyna. 2015. What integrated reporting changed: The case study of early adopters. Procedia Economics and Finance 34: 231–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, John A. C. 1969. Fact and legal theory: Shareholders, managers, and corporate social responsibility. Stanford Law Review 248: 258–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Jasper, Kerry P. Curtis, and Anne W. Smith. 2008. Implications of stakeholder concept and market orientation in the US nonprofit arts context. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 5: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Baoliang, Tao Zhang, and Shuai Yan. 2020. How corporate social responsibility influences business model innovation: The mediating role of organizational legitimacy. Sustainability 12: 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima. 2008. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics 82: 213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Rhys. 2009. Corporate Social Responsibility. In Handbook of Economics and Ethics. Edited by Jan Peil and Irene van Staveren. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Finance Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Thomas M. 1980. Corporate social responsibility revisited, redefined. California Management Review 22: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, David A., Chelsea R. Willness, and Ante Glavas. 2017. When corporate social responsibility (CSR) meets organizational psychology: New frontiers in microCSR research and fulfilling a quid pro quo through multilevel insights. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanci, Başak, Morvarid Rahmani, and L. Beril Toktay. 2019. The role of inclusive innovation in promoting social sustainability. Production and Operations Management 28: 2960–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jin-Su, Chun-Fang Chiang, Kitipop Huangthanapan, and Stephen Downing. 2015. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability balanced scorecard: The case study of family-owned hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management 48: 124–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Erin H., Chih-Chuan Yeh, Li-Hsun Wang, and Hung-Gay Fung. 2018. The relationship between CSR and performance: Evidence in China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 51: 155–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Ellen J., and Leigh Lawton. 1998. Religiousness and business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minseok, Boyoung Kim, and Sungho Oh. 2018. Relational benefit on satisfaction and durability in strategic corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 10: 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Dae-Young, Sung-Bum Kim, and Kathleen J. Kim. 2019. Building corporate reputation, overcoming consumer skepticism, and establishing trust: Choosing the right message types and social causes in the restaurant industry. Service Business 13: 363–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham Barbara, O. Pearl Brereton, David Budgen, Mark Turner, John Bailey, and Stephen Linkman. 2009. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology 51: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodinsky, Robert W., Timothy Madden, Daniel Zisk, and Eric Henkel. 2010. Attitudes about corporate social responsibility: Business student predictors. Journal of Business Ethics 91: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Mark R., and Michael E. Porter. 2002. La ventaja competitiva de la filantropía corporativa. Harvard Business Review 80: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Min-Dong P. 2008. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. International Journal of Management Reviews 10: 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, Jerome S., Jr., and James Devore. 1987. Measuring productivity in US public administration and public affairs programs 1981–1985. Administration & Society 19: 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiao. 2020. The effectiveness of internal control and innovation performance: An intermediary effect based on corporate social responsibility. PLoS ONE 15: e0234506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, Karl V., Henri Servaes, and Ane Tamayo. 2017. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. The Journal of Finance 72: 1785–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, Jane. 2018. The policy role of corporate carbon management: Co-regulating ecological effectiveness. Global Policy 9: 538–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, Irina, and Charlotte Schulz-Knappe. 2019. Credible corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication predicts legitimacy: Evidence from an experimental study. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 24: 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jintao, Licheng Ren, Wenfang Lin, Yifan He, and Justas Streimikis. 2019. Policies to promote corporate social responsibility (CSR) and assessment of CSR impacts. Business Administration and Management 22: 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luffarelli, Jonathan, and Amrou Awaysheh. 2018. The impact of indirect corporate social performance signals on firm value: Evidence from an event study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Xueming, and Chitra B. Bhattacharya. 2009. The debate over doing good: Corporate social performance, strategic marketing levers, and firm-idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Marketing 73: 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Xueming, and Shuili Du. 2015. Exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm innovation. Marketing Letters 26: 703–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, Karen, and Kellie Liket. 2011. Talk the walk: Measuring the impact of strategic philanthropy. Journal of Business Ethics 100: 445–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclagan, Patrick. 2008. Organizations and responsibility: A critical overview. Systems Research and Behavioral Science: The Official Journal of the International Federation for Systems Research 25: 371–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Peter M., and Zachariah J. Rodgers. 2015. Looking good by doing good: The antecedents and consequences of stakeholder attention to corporate disaster relief. Strategic Management Journal 36: 776–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, Hannele, and Salme Näsi. 2010. Social responsibilities of MNCs in downsizing operations: A Finnish forest sector case analysed from the stakeholder, social contract and legitimacy theory point of view. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 23: 149–74. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, Joshua D., and James P. Walsh. 2003. Misery loves companies: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Administrative Science Quarterly 48: 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí-Farinós, Jesús. 2017. Sustainability as an object of corporate social responsibility. VITRUVIO-International Journal of Architectural Technology and Sustainability 2: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Conesa, Isabel, Pedro Soto-Acosta, and Mercedes Palacios-Manzano. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and its effect on innovation and firm performance: An empirical research in SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production 142: 2374–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Joseph W. 1963. Business and Society. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Jean B., Alison Sundgren, and Thomas Schneeweis. 1988. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 31: 854–72. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, Brent, and Martina K. Linnenluecke. 2016. How firm responses to natural disasters strengthen community resilience: A stakeholder-based perspective. Organization & Environment 29: 290–307. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, Abagail, Donald S. Siegel, and Patrick M. Wright. 2006. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. Journal of Management Studies 43: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, Bulent, and Lucie K. Ozanne. 2005. Challenges of the “green imperative”: A natural resource-based approach to the environmental orientation–business performance relationship. Journal of Business Research 58: 430–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratis, Lars. 2018. Signaling responsibility? Applying signaling theory to the ISO 26000 standard for social responsibility. Sustainability 10: 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, Melinda, and Lex Donaldson. 1998. Stewardship theory and board structure: A contingency approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review 6: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, Concetta, Marcello Stanco, and Giuseppe Marotta. 2020. The Life Cycle of Corporate Social Responsibility in Agri-Food: Value Creation Models. Sustainability 12: 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass. 1990. Institutional, institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan, Linda, and Jenny Fairbrass. 2014. Managing CSR stakeholder engagement: A new conceptual framework. Journal of Business Ethics 125: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, Marc. 2011. Institutional logics in the study of organizations: The social construction of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Business Ethics Quarterly 21: 409–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, Marc, Frank L. Schmidt, and Sara L. Rynes. 2003. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies 24: 403–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panait, Mirela, Marian Catalin Voica, and Irina Radulescu. 2014. The Activity of Capital Market’s Actors: Under the Sign of Social Responsibility. Procedia Economics and Finance 8: 522–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, Jong-Chull, Prashant Mool, June-Hee Naa, and Chang-Gon Lee. 2014. The Effects of Creating Shared Value on Corporate Performance. Journal of Distribution Science 12: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina Martínez, Vicente, and Lourdes Torres Pradas. 1995. Evaluación del rendimiento de los departamentos de contabilidad de las universidades españolas. Hacienda Pública Española 135: 183–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pirnea, Ionela C., Marieta Olaru, and Cristina Moisa. 2011. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and social sustainability. Economy Transdisciplinarity Cognition 14: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. 2006. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review 84: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, John J. 1997. Personal ethics and business ethics: The ethical attitudes of owner/managers of small business. Journal of Business Ethics 16: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhepi, Gadaf, Selma Kurtishi, and Gjilnaipe Bexheti. 2013. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and innovation the drivers of business growth. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 75: 532–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Diana C. 1993. Empiricism in business ethics: Suggested research directions. Journal of Business Ethics 12: 585–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Pablo, Claudio Aqueveque, and Ignacio J. Duran. 2019. Do employees value strategic CSR? A tale of affective organizational commitment and its underlying mechanisms. Business Ethics: A European Review 28: 459–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, Katja, and Thomas Ehrmann. 2017. Reporting biases in empirical management research: The example of win-win corporate social responsibility. Business & Society 56: 840–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenhoefer, Lisa M. 2019. The impact of CSR on corporate reputation perceptions of the public—A configurational multi-time, multi-source perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review 28: 141–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiia, David H., Archie B. Carroll, and Ann K. Buchholtz. 2003. Philanthropy as strategy: When corporate charity “begins at home”. Business & Society 42: 169–201. [Google Scholar]

- Salvioli, Fabian O. 2000. Los derechos Humanos en las convenciones internacionales de la última década del Siglo XX. In Las grandes conferencias Mundiales de la década de los 90. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, Tomo I. La Plata: IRI, pp. 11–81. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Rita, Ronald Wennersten, Eduardo B. Oliva, and Walter Leal Filho. 2009. Strategies for competitiveness and sustainability: Adaptation of a Brazilian subsidiary of a Swedish multinational corporation. Journal of Environmental Management 90: 3708–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, Sarah D., Ralf Terlutter, and Sandra Diehl. 2019. Is my company really doing good? Factors influencing employees’ evaluation of the authenticity of their company’s corporate social responsibility engagement. Journal of Business Research 101: 128–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, Norma, Florian Findler, and André Martinuzzi. 2017. Exploring the interface of CSR and the Sustainable Development Goals. Transnational Corporations 24: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, Bruce, Sara A. Morris, and Barbara R. Bartkus. 2003. Comparing big givers and small givers: Financial correlates of corporate philanthropy. Journal of Business Ethics 45: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó, Dolors, and Noemí Rabassa. 2007. Responsabilidad social corporativa: Reflexiones sobre futuras líneas de investigación. In El comportamiento de la empresa ante entornos dinámicos: XIX Congreso anual y XV Congreso Hispano Francés de AEDEM. Vitoria: Asociación Española de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, Mohsin, Ying Qu, Saad Ahmed Javed, Abaid Ullah Zafar, and Saif Ur Rehman. 2020. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 253: 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawkat, Talha, Shahid Habib, and Shahzad Ahmed Khan. 2019. Socially Responsible Identity: Linking Corporate Social Responsibility, Strategic Implementation and Quality Performance. Pakistan Business Review 20: 612–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shnayder, Larissa, and Frank J. Van Rijnsoever. 2018. How expected outcomes, stakeholders, and institutions influence corporate social responsibility at different levels of large basic needs firms. Business Strategy and the Environment 27: 1689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnayder, Larissa, Frank J. Van Rijnsoever, and Marko P. Hekkert. 2016. Motivations for Corporate Social Responsibility in the packaged food industry: An institutional and stakeholder management perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 122: 212–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, Donald S., and Donald F. Vitaliano. 2007. An empirical analysis of the strategic use of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 16: 773–92. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1945. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Laura J., René Schmidpeter, and André Habisch. 2003. Assessing social capital: Small and medium sized enterprises in Germany and the UK. Journal of Business Ethics 47: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, Marck C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Wenbin, Shanji Yao, and Rahul Govind. 2019. Reexamining corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: The inverted-U-shaped relationship and the moderation of marketing capability. Journal of Business Ethics 160: 1001–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syn, Juliette. 2014. The social license: Empowering communities and a better way forward. Social Epistemology 28: 318–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliento, Marco, Christian Favino, and Antonio Netti. 2019. Impact of environmental, social, and governance information on economic performance: Evidence of a corporate ‘sustainability advantage’ from Europe. Sustainability 11: 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Ana, Marisa R. Ferreira, Aldina Correia, and Vanda Lima. 2018. Students’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Evidences from a Portuguese higher education institution. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 15: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, Carlos, and María del Pilar Rodríguez. 2014. Conceptual categories of the study organizational social responsibility. Hallazgos 11: 119–35. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, Linda, Lois S. Mahoney, Kristen Gregory, and Susan Convery. 2017. A comparison of Canadian and US CSR strategic alliances, CSR reporting, and CSR performance: Insights into implicit–explicit CSR. Journal of Business Ethics 143: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollin, Karin, and Lars B. Christensen. 2019. Sustainability marketing commitment: Empirical insights about its drivers at the corporate and functional level of marketing. Journal of Business Ethics 156: 1165–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, Linda K. 1992. Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education, and management. Journal of Business Ethics 11: 445–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Megan R., Tristan McIntosh, Shane W. Reid, and M. Ronald Buckley. 2019. Corporate implementation of socially controversial CSR initiatives: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management Review 29: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Macías, Mario E., Óscar A. Vargas-Moreno, and Luis Merchán-Paredes. 2018. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability, enabling criteria in projects management. Entramado 14: 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, José Luis, Ana Lanero, and Oscar Licandro. 2013. Corporate social responsibility and higher education: Uruguay university students’perceptions1. Economics & Sociology 6: 145–57. [Google Scholar]

- Verčič, Anna T., and Dubravka S. Ćorić. 2018. The relationship between reputation, employer branding and corporate social responsibility. Public Relations Review 44: 444–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, David J. 2005. Is there a market for virtue? The business case for corporate social responsibility. California Management Review 47: 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, Abdul, Qingyu Zhang, Yasir Rashid, Muhammad Sohail Tahir, and Muhammad Wasif Zafar. 2020. Impact of green manufacturing on consumer ecological behavior: Stakeholder engagement through green production and innovation. Sustainable Development 28: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Clarence C. 1967. Corporate Social Responsibilities. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jia, and Betty S. Coffey. 1992. Board composition and corporate philanthropy. Journal of Business Ethics 11: 771–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shuo, and Yuhui Gao. 2016. What do we know about corporate social responsibility research? A content analysis. The Irish Journal of Management 35: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED, Special Working Session. 1987. World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future 17: 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Hua-Hung Robin, Ja-Shen Chen, and Pei-Ching Chen. 2015. Effects of green innovation on environmental and corporate performance: A stakeholder perspective. Sustainability 7: 4997–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Emma. 2016. What is the social licence to operate? Local perceptions of oil and gas projects in Russia’s Komi Republic and Sakhalin Island. The Extractive Industries and Society 3: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, Piotr. 2018. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A literature overview and integrative framework. Journal of Management and Business Administration. Central Europe 26: 121–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Donna J. 1991. Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review 16: 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, Qaiser Rafique, Abdullah Al Mamun, and Irfan Ahmed. 2017. Corporate social responsibility and gender diversity: Insights from Asia Pacific. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24: 210–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Juelin, and Dima Jamali. 2016. Strategic corporate social responsibility of multinational companies subsidiaries in emerging markets: Evidence from China. Long Range Planning 49: 541–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadek, Simon, John Sabapathy, Helle Døssing, and Tracey Swift. 2003. Responsible Competitiveness: Corporate Responsibility Clusters in Action. New York: Institute of Social & Ethical AccountAbility. [Google Scholar]

- Zeimers, Geraldine, Christos Anagnostopoulos, Thierry Zintz, and Annick Willem. 2019. Organisational learning for corporate social responsibility in sport organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly 19: 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, Fabrizio. 2017. CSR initiatives as market signals: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics 146: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Haidi, Qiang Wang, and Xiande Zhao. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and innovation: A comparative study. Industrial Management & Data Systems 120: 863–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zyznarska-Dworczak, Beata. 2018. Legitimacy Theory in Management Accounting Research. Problemy Zarządzania 16: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez-Gomez, S.; Arco-Castro, M.L.; Lopez-Perez, M.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030060

Rodriguez-Gomez S, Arco-Castro ML, Lopez-Perez MV, Rodríguez-Ariza L. Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art. Administrative Sciences. 2020; 10(3):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030060

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez-Gomez, Sara, Maria Lourdes Arco-Castro, Maria Victoria Lopez-Perez, and Lazaro Rodríguez-Ariza. 2020. "Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art" Administrative Sciences 10, no. 3: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030060

APA StyleRodriguez-Gomez, S., Arco-Castro, M. L., Lopez-Perez, M. V., & Rodríguez-Ariza, L. (2020). Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030060