Abstract

There is a vast literature on Total Quality Management (TQM), one of the most influential management concepts introduced during the twentieth century. In the TQM literature, there are multiple conflicting views on TQM’s historical popularity trajectory. In the past, commentators have debated whether TQM represents a lasting trend, or instead should be considered a more short-lived management fad or fashion. Since the 1990s, skeptics have speculated about the imminent fall, death, and burial of TQM, and even delivered eulogies. However, others claim that the level of interest has picked back up and that TQM is alive and well. Therefore, this paper attempts to synthesize and reconcile these differing views on the long-term trajectory of TQM and provide an updated picture and status report, taking into account the latest findings and developments in research and practice. The evidence reviewed in this paper suggests that, even though TQM has become much less noticeable in public management discourse compared to the heydays of the 1980s and 1990s, the concept has persisted and even to this day remains widely used by organizations worldwide.

1. Introduction

Total Quality Management (TQM) can be defined as a “business discipline and philosophy of management which institutionalizes planned and continuous business improvement” (Hill 1995, p. 36). TQM is “the most celebrated and widely adopted form of quality management” (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995b, p. 8) and one of the most influential management concepts and ideas (Hindle 2008).

Although the roots of TQM can be traced back several decades to the post-war period (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a), the concept of TQM did not take center stage in the business world until the 1980s when it started enjoying immense popularity. According to Rüling (2005), it was perhaps the biggest management fashion. Rüling (2005) was not alone in making this observation, as the meteoric rise of TQM during the 1980s and 1990s led many researchers to suggest that there was much hyping of the concept and perhaps a fashion-like aspect involved in its rapid rise and popularization (Cole 1999; Collins 2000; David and Strang 2006; Ehigie and McAndrew 2005; Giroux 2006; Jackson 2001; Larsen 2001; Mueller and Carter 2005; Rüling 2005; Staw and Epstein 2000; Thawesaengskulthai and Tannock 2008; Van Der Wiele et al. 2000; Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a; Zbaracki 1998).

In recent years, the buzz and hype surrounding TQM has waned considerably. The concept is no longer perceived as new and has been pushed into the background by newer concepts such as Big Data Analytics, Agile Management, and Industry 4.0 (Madsen and Stenheim 2016; Madsen 2019; Madsen 2020; Rigby and Bilodeau 2018). However, despite lower levels of attention and interest, the TQM concept does not appear to have been abandoned in organizational practice. On the contrary, the concept has had considerable staying power and continues to impact organizations well into the twenty-first century (Dahlgaard-Park 2011). Evidence suggests that TQM is still widely used several decades after its inception. For example, TQM has steadily remained in the top 25 of the consulting firm Bain & Company’s “Management Tools and Trends Survey” since 1993, and in the newest edition, TQM has broken into the top 10 in terms of use (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018).

1.1. Research Goals

The intense hype and buzz surrounding TQM during the late 1980s and early 1990s led to a flurry of academic papers suggesting that the concept could be the latest in the long line of management fads and fashions to sweep the organizational world. Some commentators went as far as to speculate about TQM’s imminent death and burial. However, as indicated in the introduction, the various reports (e.g., Albrecht 1992a, 1992b; Bohan 1998; Byrne 1997; Paton 1994) about the death and burial of TQM may have been exaggerated and premature. Several more recent studies indicate that TQM is still alive both in academic circles and in business practice (Bergquist 2012; Douglas 2006; Rahman 2004; Rigby and Bilodeau 2018; Sower et al. 2016; Williams et al. 2004).

In other words, there is arguably a need to synthesize and reconcile the many conflicting views on TQM’s historical popularity trajectory. The current paper aims to do this by reexamining the various accounts available in the literature on TQM. The paper utilizes management fashion theory (Abrahamson 1996; Abrahamson and Piazza 2019; Benders and Van Veen 2001; Kieser 1997) as a theoretical lens and sensitizing framework. Management fashion theory is well-suited to providing a birds-eye view of the evolution and lifecycle of TQM since it is a macro-level theory focusing on the field-level evolution of concepts and ideas (Madsen and Slåtten 2015a; Perkmann and Spicer 2008).

Using arguments from management fashion theory has a long tradition in the context of TQM (Carnerud 2019; Collins 2000; David and Strang 2006; Giroux 2006; Mueller and Carter 2005; Staw and Epstein 2000; Thawesaengskulthai and Tannock 2008). Hence, this is not the first study to suggest that management fashion theory has applicability in explaining and understanding the dynamics of the marketplace for TQM. However, most of these earlier contributions that have utilized management fashion-type arguments in the context of TQM are by now more than a decade old. In the author’s view, time is, therefore, ripe to reexamine the historical popularity trajectory of TQM and to account for the latest developments in terms of discourse around and use of the concept in practice.

1.2. Structure

The rest of the paper is structured in the following way. Section 2 lays out the research approach. Section 3 provides a brief historical overview of the origins and evolution of the TQM concept. Section 4 provides an analysis of the framing and characteristics of the TQM concept. Section 5 and Section 6 analyze the supply and demand sides of TQM, respectively. In Section 7 a discussion of the findings follows, before Section 8 concludes the paper and maps out directions for future work in the area.

2. Research Approach

The study aims to obtain a birds-eye overview of the historical popularity trajectory of TQM. Using the terminology of Miller et al. (2018), the current research examines TQM as a global trend. In previous related studies of management concepts and ideas, researchers have referred to this process of assessing the impact of management concepts as creating a “mosaic” (Morrison and Wensley 1991) or “overall picture” (Nijholt and Benders 2007).

In this study, the overall research approach can be characterized as explorative and qualitative. The picture of TQM’s popularity trajectory emerges as a result of patching together findings from a wide range of existing studies on TQM, both from the scholarly and practitioner-oriented literatures. The search for literature can most accurately be described as a snowballing-type procedure (see e.g., Felizardo et al. 2016; Wohlin 2014; Wittrock 2016). The search process started by identifying key papers that previously have discussed TQM as a managerial fad, fashion, or trend (Carnerud 2019; Collins 2000; David and Strang 2006; Giroux 2006; Mueller and Carter 2005; Staw and Epstein 2000; Thawesaengskulthai and Tannock 2008). These key papers on TQM were then subject to both backward snowballing (examining the reference lists of the key papers) and forward snowballing (examining more recent work that has cited the key papers).

Following this type of research approach has several limitations which should be considered carefully. For example, there are potential biases related to the author’s selection and reading of prior studies as well as issues related to historical retrospection. However, from a practical and pragmatic standpoint, following such an approach is necessary for several reasons. First of all, researching the historical evolution of management concepts and ideas is a formidable task since management concepts are ideational phenomena (Benders and Van Bijsterveld 2000; Benders and Van Veen 2001; Strang and Wittrock 2019). Such methodological problems have also been noted in the context of research on TQM. For example, it has been observed that studying quality concepts and programs is “an elusive topic of study” (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995b, p. 1).

Another issue is related to the use of secondary sources. To be able to reconstruct the history and evolution of a particular management concept, it is necessary to utilize and rely heavily on secondary sources. As Nijholt and Benders (2007) note, the use of secondary sources is often needed to say something about the impact of management concepts. However, they also point out that the use of secondary sources is potentially problematic from a methodological standpoint since other researchers have collected such data at different times and for different purposes.

3. A Brief History of TQM

This section provides a historical overview of the origins and evolution of the TQM concept. Researchers have written extensively on the historical emergence and evolution of TQM (Bergquist et al. 2008; Brown 2013; Cole 1992, 1998; Dahlgaard-Park 2011; Giaccio et al. 2013; Hackman and Wageman 1995; Harris 1995; Juran 1995; Martínez-Lorente et al. 1998; Miller et al. 2018; Sanderson 1995; van der Wiele and Brown 2002; Weckenmann et al. 2015; Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a; Zairi 2013, Zbaracki 1998). Since the history of TQM is arguably well-documented in other contributions, this section will not provide a comprehensive genealogy of TQM. Instead, it gives a brief sketch of the origins and evolution of TQM, with a particular focus on the later stages (i.e., the mid-2000s and onwards) of TQM evolutionary trajectory. This period has so far received relatively less attention in the TQM literature.

3.1. Origins and Emergence

Modern quality management tools were developed during the 1930s and 1940s (Giroux 2006), and quality approaches have been used in industry since the 1930s (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). TQM has roots that can be traced back to the post-war period in Japan. Embryonic versions of the concept were developed in Japanese companies during the 1950s and 1960s based on the thinking of American quality gurus (Hindle 2008, p. 191). Therefore, a number of quality thinkers such as Deming, Juran, Crosby, and Feigenbaum can be considered pioneers of the concept (Krüger 2001). These pioneers worked in industry and for governments, and typically hailed from the practice domain, instead of academic institutions (Ehigie and McAndrew 2005). Hence, the emergence of TQM was, to a large extent, driven by experimentation and development in business practice, and by contrast, academic researchers were mostly passive during this phase (Wilkinson and Willmott 1996).

While the previous section showed that TQM has roots that date back several decades, it took several decades before TQM took off at the international level. The 1980s is usually considered the time period when TQM achieved its breakthrough in terms of popularity (Giroux 2006). For example, researchers have documented that TQM became popular in the United States (Cole and Scott 2000; Gibson and Tesone 2001) as well as in the UK (McCabe and Wilkinson 1998) and Australia (Dawson and Palmer 1993; Lu and Sohal 1993; Rahman 2001; Sohal and Terziovski 2000) around this time. For example, the 1980s have been called a “revolutionary era” for quality in the US (Dahlgaard-Park 2015, p. 810).

Why did the interest in TQM “explode” during the 1980s? An important reason was that the concept became”socially appropriate” and in previous research, it has been shown that being associated with TQM increased a firm’s legitimacy and that this led to bandwagon adoption of TQM (Staw and Epstein 2000, Westphal et al. 1997). Westphal et al. (1997) found that the organizations that adopted TQM during the fashion boom tended to imitate other TQM users, while in the later stages (post-TQM boom), adopters tended to customize and adapt TQM to a greater extent.

3.2. Evolution

The popularity of TQM continued at full steam into the 1990s. Several authors commented on the popularity of TQM during the 1990s, noting that it was the “decade of quality” (Rajagopal 1995) and that the concept was a “corporate religion” (Hill 1995, p. 48). Others noted that the concept acquired a paradigmatic status in management thinking during this time (Watson and Rao Korukonda 1995). In the early 1990s, Spenley (1992) commented on the hyperactivity surrounding TQM: “[t]here is no doubt that there are more TQM conferences, magazines etc. than ever and that there is a drive for many companies to be featured as successful TQM implementors in commercial and government publications” (p. 8).

Despite the high level of activity related to TQM during the 1990s, this period was also a time when TQM, for the first time, faced severe headwinds. During the early to mid-1990s, commentators were increasingly growing skeptical and critical of TQM, and during the late 1990s, there was a backlash against TQM (Hindle 2008, p. 192).

Partly this can be explained by the fact that, during the 1990s, negative stories about TQM started to surface, which meant that the TQM concept became associated with failures and “a dirty word” (Bohan 1998, p. 13). This trend continued into the twenty-first century. In the words of Dahlgaard-Park (2015, p. 808): “during the first 10 years of the new millennium, the term TQM seems to have lost its attractiveness in the industrialized parts of the world.”

In general, TQM failed to live up to the high expectations, and in the business community, there was rising disappointment and disillusionment (Doyle 1992, Schaffer 1993). TQM was no longer seen as the panacea that companies were waiting for. The disappointment is reflected in Bain & Company’s surveys, where TQM fell in popularity during this time period. David and Strang (2006) suggest that 1992 to 2001 was “a period during which TQM went from the limelight to the background of the management stage.” As they point out, there was a “fashion bust” (David and Strang 2006), and the concept became worn out.

Many commentators were, therefore, pessimistic with respect to the future trajectory of TQM and painted a relatively bleak picture. Speculations about the demise of TQM were made as far back as the early 1990s (Macdonald 1993). Around this time, some started questioning the viability of TQM (Paton 1994). (Bohan 1998) Commentators started talking about the “last days” of TQM (Albrecht 1992b), and the need to “give TQM a decent burial” (Albrecht 1992a, p. 272). Byrne (1997) referred to TQM as “dead as a pet rock.” Others delivered eulogies (Bohan 1998).

However, in hindsight, it appears that some of these views were too pessimistic. Ehigie and McAndrew (2005) found that even though there were indications that TQM looked faddish, they could not conclude at the time that it was only a management fad. Some researchers have even documented that there has been a resurgence in the interest in TQM (Rahman 2004, Williams et al. 2004) and that the concept is still alive (Bergquist 2012, Douglas 2006, Sower et al. 2016) and widely used by organizations worldwide (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018).

4. Characteristics and Framing of TQM

This section analyzes the characteristics and framing of TQM. Before proceeding, however, it is necessary to define what is meant by the notion of a management concept. In the literature on management concepts and ideas, there is a multitude of partly overlapping terms such as management tools, management techniques, and management innovations (Bort 2015, Wittrock 2016). In this paper, the author will refer to TQM as a “management concept.” According to Benders and Verlaar (2003, p. 758), management concepts are “prescriptive, more or less coherent views on management.” TQM can clearly be considered a management concept since it has a “normative thrust” (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995b, p. 15) and gives clear recommendations to managers about how to organize and structure their organization to improve quality practices, customer satisfaction, and ultimately financial performance.

4.1. Label

In the management fashion literature, it is frequently pointed out that popular management concepts are labeled in an engaging and appealing way, often in the form of a slogan or buzzword (Cluley 2013; Kieser 1997; Røvik 1998). Another typical feature of management concepts and ideas is that they are usually associated with two or three letter acronyms (Grint 1997). Grint (1997) uses TQM as a prime example of a three-letter acronym. Over time, even though the popularity of the TQM label and acronym has varied, it can still be considered a widely used and institutionalized acronym (Yong and Wilkinson 2001).

Numerous authors have noted that TQM resembles a buzzword (Bensimon 1995, Collins 2000, Qi 1999). As pointed out by Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b, p. 1), quality is a term is that “can be used to legitimize all sorts of measures and changes in the name of a self-evident good.” Quality triggers positive associations, which makes it an appealing concept (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995b, p. 2). It is difficult to reject the notion “that we should all strive to improve the quality of products and services” (Tuckman 1995, p. 56). Munro (1995, p. 131) asks, “Who can be against quality?”

However, as noted in Section 2, during the 1990s, the TQM label started to get “worn out” as a result of negative publicity. As Cole (1999) points out, the label became a liability rather than an asset. According to Hensler (2004), there was a general movement away from using the term “quality.”

While there has been a significant reduction in the use of the label TQM in public management discourse, it has not disappeared completely, evidenced by, for instance, a wide range of journals focusing on quality issues (e.g., TQM Journal). Moreover, surveys show that it is still used to a large extent by organizations worldwide (Rigby and Bilodeau 2015).

4.2. Performance Improvements

Another essential characteristic of management concepts is the promise of substantial performance enhancements (ten Bos 2000). Proponents of new management concepts highlight the risk of being at a competitive disadvantage if the concept is not adopted (Heusinkveld 2004; Kieser 1997). Moreover, proponents tend to use lofty, emotionally charged, and upbeat rhetoric to describe the benefits of adopting and implementing new management concepts. In the case of TQM, such claims of performance improvements are easy to identify. During the boom phase, proponents of TQM would typically talk of a “revolution,” and TQM was widely viewed as a “silver bullet” and panacea (Douglas 2006).

However, as news of failed TQM implementations surfaced and started to circulate in the business community, it became harder to continue to make these claims and promises. Over time, claims about TQM became more nuanced, and TQM researchers started highlighting that the performance effects of TQM to a large degree depend on how the concept is interpreted and implemented in practice (Easton and Jarrell 1998, Powell 1995).

4.3. Interpretive Space

Another characteristic of management concepts is that they are ideational innovations which have a high degree of conceptual ambiguity and leave substantial room for interpretation (Benders and Van Bijsterveld 2000; Benders and Van Veen 2001; Giroux 2006). This feature of a management concept is sometimes referred to as “interpretive space” or “interpretive viability” (Benders and Van Veen 2001; Clark 2004) and means that these concepts can be interpreted in a multitude of different ways.

In the case of TQM, it is easy to identify a high degree of interpretive space. Table 1 provides some illustrative quotes about the interpretive space of the TQM concept. In the literature, it is often pointed out that there is a large number of different definitions of TQM (Dahlgaard-Park 2015) and that there is confusion about the exact meaning of the concept (Zairi 1994). There are also semantic issues, as there is a lack of a common interpretation of the term “quality” (Bergquist et al. 2005). Some consider TQM to be one of several quality management philosophies (Fredriksson and Isaksson 2018). Therefore, it should come as little surprise that there is no agreed-upon definition of TQM (Boaden 1997; Hackman and Wageman 1995), and a lack of consensus (Nwabueze 2001).

Table 1.

Illustrative quotes about the interpretive space of Total Quality Management (TQM).

It has been suggested that the TQM concept can be viewed as a collection of different tools and methodologies (Spencer 1994). For example, Cua et al. (2001) identified nine key tools and practices that usually are considered part of TQM, such as customer involvement, cross-functional product design, strategic planning, and process control.

Moreover, there are multiple schools of thought within the quality movement (Giroux and Landry 1998; Krüger 2001). Adding to the complexity is the fact that there are many different concepts, ideas, tools, and techniques associated with the quality movement (Andersson et al. 2006, Dahlgaard-Park 2011). Therefore, TQM could be viewed as an umbrella concept encompassing many different tools, techniques, and approaches.

Interpretive space and vagueness make it easier for a concept to “flow” in a community of organizations (Røvik 1998, 2002). Giroux (2006) found that the ambiguity of TQM varied over time and that the concept became more vague and ambiguous as it gained popularity. Conceptual ambiguity also has advantages when it comes to a concept’s popularity potential. A degree of ambiguity and wide room for interpretation helps a concept become widely diffused. This is because different groups of actors can see value and potential in the concept; and can shape and adapt it to fit their particular needs and interests (Benders and Van Veen 2001; Kieser 1997). Benders and Van Veen (2001, p. 38) argue that “… any concept must necessarily lend itself to various interpretations to stand a chance of broad dissemination.”

A high level of ambiguity and a wide room for interpretation also means that the TQM concept is easily mixed and blended with other ideas and approaches, which is an advantage since organizations often use several concepts and ideas simultaneously. For example, it has been suggested that TQM has links to a number of other similar process improvement concepts and approaches such as Six Sigma and Lean (Boaden 1996; Goeke and Offodile 2005; Näslund 2008). The room for interpretation also leads to a wide range of translations of TQM in practice (Giroux and Taylor 2002). In previous research, it has been noted that an extensive range of applications are referred to as TQM (Hill 1995, p. 48).

4.4. Universality

Universality is a crucial characteristic of management concepts and ideas (Kieser 1997; Wittrock 2015). Management concepts are typically decontextualized from the particularities of any given organization, industry, or national market and are presented as applicable across the board (Huczynski 1992; Lillrank 1995; Røvik 2007). Universality is seen to a great extent in the case of TQM. Proponents and propagators of TQM typically argue that quality is something that every organization has to take seriously if they are to remain competitive.

Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b, p. 9) noted the “abstract and universal character of TQM philosophy.” Another interesting observation related to TQM, is that the concept is viewed as beneficial to nearly any type of organization. In the words of Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b, p. 16) “[I]t is simply taken for granted that quality management is benign and universally beneficial”.

Tuckman (1995, p. 63) argues that TQM became an increasingly universalized prescription during the late 1980s. There are numerous examples of TQM applications and adaptations across different sectors, such as health care (Motwani et al. 1996; Yang 2003; Øvretveit 2000), education (Peck and Reitzug 2012; Stensaker 2007; Williams 1993), and social welfare (Berman 1995; Martin 1993; Mäntysaari 1998), to name just a few examples.

5. The Supply Side of TQM

The market for fashionable management concepts and ideas has both a supply side and demand side (Abrahamson and Reuben 2014; Abrahamson 1996). This section provides an analysis of the supply side of the TQM concept. According to management fashion researchers, the actors on the supply side (e.g., consulting firms, management gurus, and business media) are referred to as the “fashion-setting community” (Abrahamson 1996) or the “management fashion arena” (Jung and Kieser 2012). In previous research, it has been pointed out that many types of fashion-setting actors have been involved in the diffusion and dissemination of TQM (Collins 2000; David and Strang 2006; Jackson 2001; Larsen 2001; Thawesaengskulthai and Tannock 2008; Zbaracki 1998).(Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a) In the following, the various actors involved in the supply of TQM will be described and analyzed in greater detail, including how their involvement has varied over time.

5.1. Consulting Firms

Consulting firms are important propagators and promoters of new management concepts (Heusinkveld and Benders 2012b; Heusinkveld 2013; Jung and Kieser 2012). The role of consulting firms in the diffusion of TQM has been duly noted in previous research (David and Strang 2006; Jung and Lee 2016; Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a). Tuckman (1995, p. 71) pointed out that a quality-related consulting industry mushroomed during the 1980s. David and Strang (2006) studied the market for TQM consulting services. They found that during the boom phase of the 1980s, many new consulting firms entered the TQM consulting market, while during the 1990s, there were fewer new entrants, and many firms exited the market.

Furthermore, they found that in the boom phase, the consultancy market was dominated by generalists with relatively little technical knowledge. However, in the decline phase, when TQM fell out of fashion, these generalists pulled out, and specialist consultants with more sophisticated technical understanding took over. These specialists were more committed and knowledgeable providers of TQM consulting services (David and Strang 2006).

5.2. Business Schools

Business schools play an essential role when it comes to the anchoring of new concepts in academic research and discourse (Engwall and Wedlin 2019; Sahlin-Andersson and Engwall 2002; (Douglas 2013) Business school professors were not actively involved in the field of TQM during the early stage (Miller 1996), and there were calls for business schools to take a more active role, and to develop more courses about TQM and related issues (Zairi 1994). However, as the concept became more established during the latter part of the 1990s, professors of quality were appointed (Larsen 2001).

It has been noted that a possible explanation for academia’s lack of involvement was that there was a certain level of scholarly disdain for the notion of quality. In the words of Wilkinson and Willmott (1996, p. 55), “academics who, potentially, could provide a broader assessment have tended to regard quality initiatives as too faddish and superficial to be worthy of sustained examination.” The passive role of academia in the early phase meant that quality gurus could dominate the field (Wilkinson and Willmott 1996, p. 55). Academics have been “slow to get to grips with TQM, leaving the quality gurus to enjoy a virtual monopoly over the discussion” (Hill and Wilkinson 1995, p. 8). The relative absence of academics in the early phase could also explain why there is “no single theoretical formalization of total quality” (Hill 1995, p. 36).

Over time, academics have taken a more active role, and a large body of research on TQM has accumulated (Carnerud 2018; Carnerud and Bäckström 2019; Ehigie and McAndrew 2005; Larsen 2001, Odigie 2015). Some of the research has taken a more balanced approach, even using critical theories to shed light on the concept (Larsen 2001; Wilkinson and Willmott 1995a; Yong and Wilkinson 1999). Much of the research has been published in journals with an explicit focus on TQM and related issues. While it has been noted that some TQM-related journals have disappeared (Giroux 2006), there are still several academic journals focusing heavily on the TQM concept (e.g., The TQM Journal, and Total Quality Management and Business Excellence). For example, The TQM Journal has been around for 30 years and is still publishing multiple issues per year (Douglas 2013).

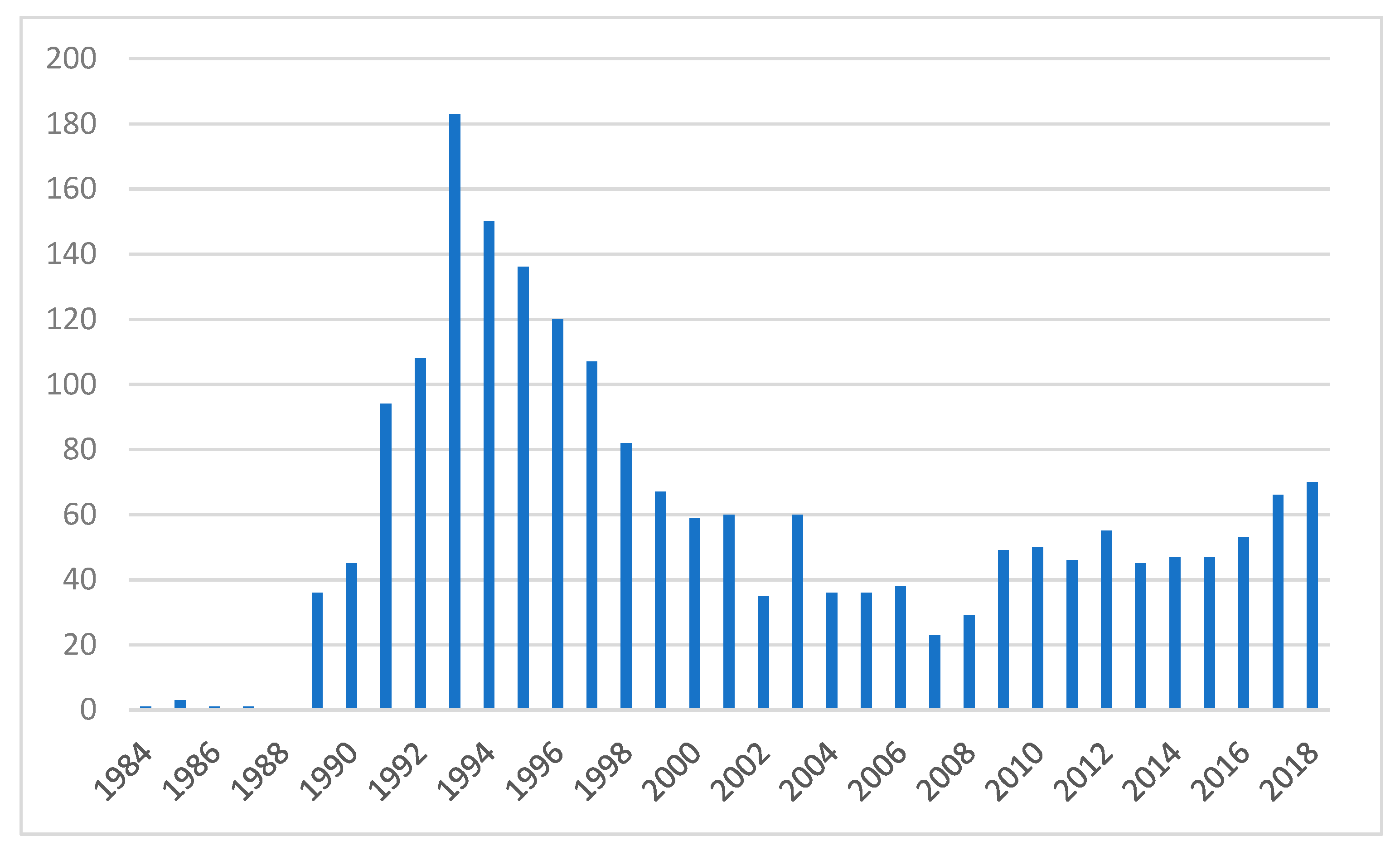

During the height of TQM’s popularity, journals typically published special issues about quality (Giroux 2006). Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. (2013) analyzed the popularity of the TQM paradigm using Google Scholar. The number of publications can be seen as an indicator of the popularity of TQM (Näslund 2008). As pointed out by Giroux (2006), bibliometric studies have shown that there was a rise in the number of articles about TQM during the late 1980s, followed by a fall during the early 1990s. Rüling (2005) noted that, based on bibliometric studies, it could be argued that TQM was the most important management fashion.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the number of Scopus-indexed articles containing TQM in the article title. Figure 1 clearly shows that the volume of articles has dropped considerably since the boom period during the early-to-mid 1990s. However, since the late 1990s, there has been a period of relative stability, which could indicate a steady state. However, it should be noted that bibliometric research has shown that in recent decades there has been an overall growth in the total volume of indexed articles (Bornmann and Mutz 2015). Therefore, taking into account this general growth pattern, it can be argued that there has been a relative decline in the market share of TQM as a research topic even though the absolute number of articles has stayed relatively stable over time.

Figure 1.

Scopus-indexed articles with “Total Quality Management” in the title.

5.3. Management Gurus

Management gurus develop and popularize new management concepts and ideas (Collins 2019; Huczynski 1993; Jackson 2001). Earlier it was noted that academics were relatively passive in the early phase of TQM’s development. This vacuum created an opening for management gurus, who assumed a central role in the TQM arena. Wilkinson and Willmott (1996, p. 55) comment that “quality gurus have enjoyed a virtual monopoly over the definition and discussion of the field.”

Several commentators have noted that there have been a large number of influential quality gurus (Bendell et al. 1995; Miller 1996; Tuckman 1995; Zairi 2013). Zairi discusses a wide range of gurus that have influenced TQM, including Deming, Juran, Crosby, Feigenbaum, Ishikawa, Conway, Tagushi, Shingo, and Ouchi (Zairi 2013).

Others have highlighted the role of Deming, Juran, and Crosby (Miller 1996) as well as Feigenbaum and Ishikawa (Ghobadian and Speller 1994). Tuckman (1995, p. 63) argues that Crosby was the most charismatic promoter of TQM. Similarly, Douglas (2007) notes that Crosby could “hold an audience of academics and industrialists spellbound as he expounded the principles of quality management.” During the 1990s, a new generation of TQM gurus appeared, led by Oakland (Wilkinson and Willmott 1995b, pp. 8–9). Overall, the vital role played by (more or less) charismatic quality gurus means that TQM, at least in some ways, resembles a religious movement (Walshe 2002) with charismatic leaders (e.g., quality gurus) and ardent followers of the different quality gurus.

5.4. Organizations and Institutes

One salient feature of the supply side of TQM is the importance of organizations and institutes focusing on disseminating information about the importance of quality and providing guidance to potential adopters of TQM grappling with quality-related issues and practices. These organizations and institutes have played an essential role in the professionalization of the quality field (Antony 2013).

Many of the infrastructures for the dissemination of knowledge about quality emerged in the post WW2 era. For example, the American Society for Quality (ASQ), formerly the American Society for Quality Control (ASQC), was founded in 1946 (Dahlgaard-Park 2015; Giroux 2006). Another important organization in the US is the American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC). In Europe, The British Quality Association, European Foundation for Quality Management, and the European Center for TQM are examples of influential organizations.

These organizations and institutes have been influential in terms of building networks between users, providing education/training, and issuing awards. However, the role and importance of these organizations have varied over time. Giroux (2006) argues that the number of members can measure the interest in TQM. For example, the membership in ASQ tripled during the late 1980s and early 1990s, then stabilized, before it started falling around the turn of the millennium.

5.5. Awards

There have also been many awards related to quality (Bohoris 1995; Cauchick Miguel 2001; Hendricks and Singhal 1999; Kennedy 2019; Laszlo 1996). The Deming Prize, established in 1951, was the first quality award in Japan (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). This prize served as the blueprint for other quality awards set up in other parts of the world later (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). During the 1980s, the US Congress passed the National Quality Improvement Act. The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award was established in 1987 (Cole 1999; Shetty 1993) and was followed by the introduction of local awards in the different US states.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, similar types of awards spread to other parts of the world. The Australian Quality Award was established in 1988 (Dahlgaard-Park 2015) and the European Quality Award in 1991 (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). Another example is the European Quality Award Model (Conti 2007) and a similar award was given out in Brazil (Cauchick Miguel 2001). By the early 2000s, it was reported that there were national and regional awards in 16 countries (Tan 2002; Vokurka et al. 2000). Dahlgaard-Park (2015) states that a common assumption is that there are at least 90 national and regional quality awards worldwide.

The concept of “quality awards” has drawn considerable criticism. Some researchers are highly skeptical of such awards. Macdonald (1998) calls these awards “Business Oscars” which do little more than legitimize particular fashionable approaches. Macdonald (1998, p. 332) writes that “the whole concept of individual company awards for quality or any other aspect of business performance is suspect.” At the same time, awards provide some value in bringing quality to the forefront of managers’ attention.

Over time, however, the role of quality awards has diminished in importance. By the late 1990s, the number of applications for awards had already started falling (Harmon and Laird 1997). Similarly, the number of applications for the Baldrige Award also declined during the late 1990s (Giroux 2006). Moreover, a recent study finds that the Baldrige Award is on its way out (Cook and Zhang 2019).

5.6. Conferences and Seminars

The conference/seminar scene plays a crucial role in the diffusion and legitimization of new management concepts and ideas (Kieser 1997). The conference and seminar circuit serves as a setting where managers are exposed to new management concepts and ideas (Madsen 2014; Powell et al. 2006). During TQM’s upswing phase, organizations would typically send delegates to TQM conferences to learn about the concept and to network with other users of TQM.

The activity on the conference and seminar scene can be seen as a measure of the popularity of TQM (Dahlgaard-Park 2011). Spenley (1992) noted that there were more TQM conferences than ever. Larsen (2001) mentions several examples of TQM conferences that were established and grew in importance during the late 1980s and 1990s. Kravchuk and Leighton (1993) commented that “one sign of the current interest in TQM is the large number of TQM conferences, workshops, and training seminars run for government executives.” There was also an increase in TQM-related training during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Giroux 2006). Table 2 displays some quotes that illustrate the intense activity during the boom period in the early 1990s.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotes about the role of conferences/seminars related to TQM.

However, the high level of interest in conferences and seminars related to TQM was not sustained over time. Just a few years later, Harmon and Laird (1997) pointed out that attendance at TQM conferences had fallen greatly since the early 1990s. This trend seems to have continued into the new millennium, and during the mid-2000s, Douglas (2007) lamented that conferences were not well attended and often by the same group of people.

5.7. Business Media

Different types of business media organizations (e.g., publishers of newspapers, magazines, and books) are important in the diffusion of management concepts and ideas (Barros and Rüling 2019). In recent years, much of the discourse around management concepts and ideas has shifted from traditional print media to social media (Barros and Rüling 2019; Madsen and Slåtten 2015b).

However, for the purposes of this paper, most of the analysis will focus on print-media discourse related to TQM. There is a natural explanation for why TQM has not had a large footprint in social media. TQM can be considered an “old” management concept, and social media were not available during the concept’s boom phase in the 1980s and 1990s. While there is some activity related to TQM on social media platforms such as Linkedin and Twitter, it is not nearly as intensive as the discourse related to new concepts such as Big Data Analytics, Agile Management and Industry 4.0 (Madsen and Stenheim 2016; Madsen 2019; Madsen 2020).

In previous research on TQM, it has been noted that business media organizations have been involved in several different ways. In the beginning, the business media functioned as an enthusiastic cheerleader of TQM, drumming up support by publishing mostly positive and upbeat pieces about the concept. Later this changed, when articles started questioning the merits of the concept (Yong and Wilkinson 1999). As noted by Hendricks and Singhal (1999), during the 1990s, there were, for example, numerous articles critical of TQM in high-profile business newspapers and magazines such as The Economist, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, and USA Today. The TQM craze was also extensively satirized in the Dilbert cartoons (Langlois 2000). In addition, the intensity of TQM discourse in these channels started decreasing. Ehigie and McAndrew (2005) noted that were indications of a decrease in the attention that the concept was receiving in the popular press.

Books about quality have also played an important role in the diffusion and dissemination process. There is a long list of books about TQM (Bank 1992; Dale and Cooper 1992; Drummond 1992; Garvin 1988; Oakland 1989). As pointed out by Dahlgaard-Park (2015), few of the books published before 1990 used the term TQM explicitly, and the first book with title TQM was published by James Oakland (Oakland 1989). Most of the TQM books have typically been practitioner-oriented in nature, and authored by management gurus and consultants, based on experiences from organizational practice and/or consulting work. Books about TQM have only, to a limited extent, built on an academic/theoretical foundation. As Larsen (2001) notes, these books were mostly authored by consultants. During the maturity phase of the late 1990s, academics also started writing textbooks. These more scholarly books generally took a more balanced and analytical approach to the concept.

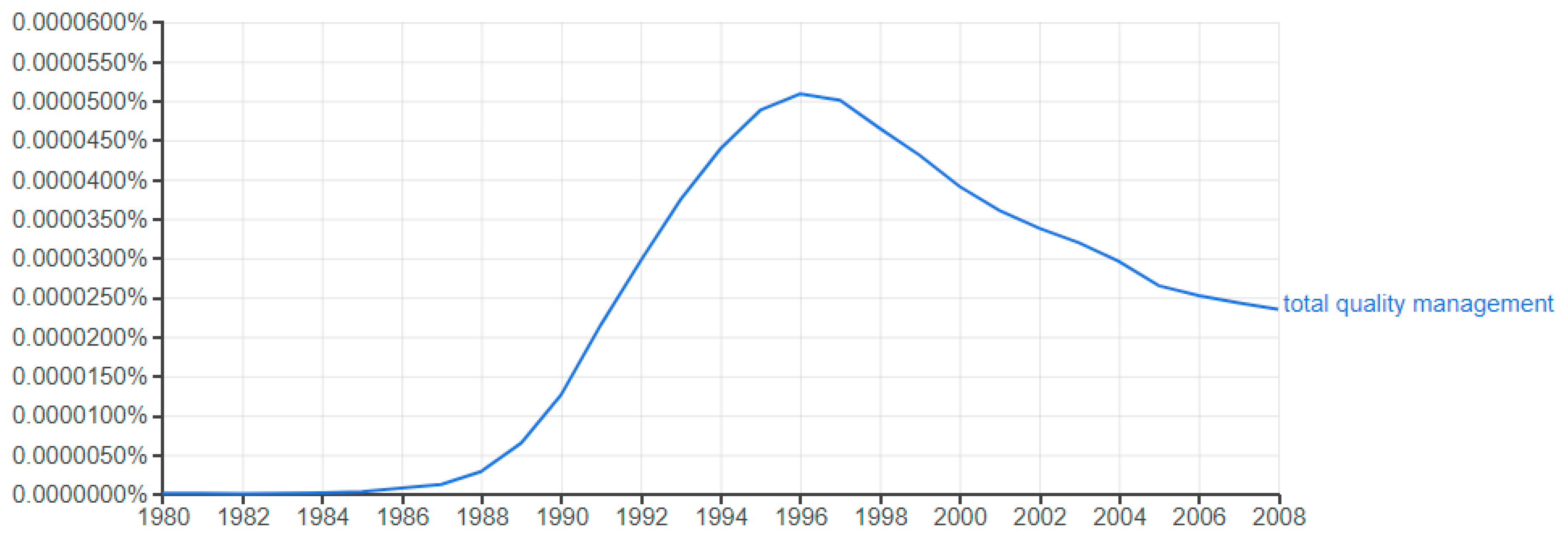

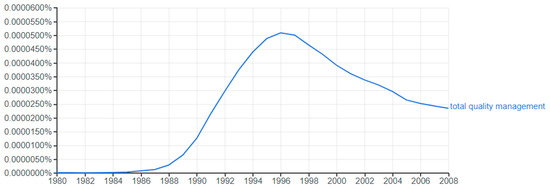

Another way to assess the role of books in the popularization of TQM is to use the Google Books Ngram Viewer (Michel et al. 2011). This analytical tool shows how often the term “Total Quality Management” is mentioned in books in the period up to 2008 (Figure 2). As Figure 2 shows, the use of the TQM term peaked during the mid-1990s and entered a period of steady decline during the 2000s. The shape of the curve thus resembles the typical inverted U-shape often documented in studies of management fashions (Abrahamson 1996).

Figure 2.

Data source: Google Books Ngram Viewer, available at http://books.google.com/ngrams, retrieved 07 December, 2017.

5.8. Summary

A broad spectrum of actors have been involved in building and sustaining the popularity of the TQM concept. In terms of driving the theorization and legitimation of the concept, the quality gurus have played a particularly influential role, for example, by translating organizational practices and framing them as theorized management concepts that can be applied irrespective of context. Consultants have also played a central role, particularly in the boom phase, when most consulting firms offered TQM services. Quality centers and institutes have played an important supporting role on the supply side by carrying out a range of activities to drum up and sustain the interest in TQM. This has, for instance, been done via quality awards. Business media also took on a role as cheerleaders during the boom years, but over time the sentiment of business media articles has turned more critical and skeptical. Social media have not played an influential role in shaping the trajectory of TQM. However, it can be argued that the relative neglect these days has a negative effect on the overall perception of TQM’s relevance and timeliness. Finally, academics were passive in the early phase, but have become increasingly more active in recent years.

6. The Demand Side of TQM

This section examines the demand side of TQM, i.e., organizations and managers, that are potential users of the concept. It can be challenging to get data about the uptake of TQM in practice. Assessing the use of management concepts by organizations on the demand side is a general problem in research on management concepts and ideas (Benders and Van Veen 2001; Clark 2004; Nijholt and Benders 2007). Therefore, this section utilizes several different sources of evidence that together will shed light on various aspects of the demand side impact of TQM: (1) search interest, (2) adoption/diffusion, (3) implementation, and (4) expectations and effects.

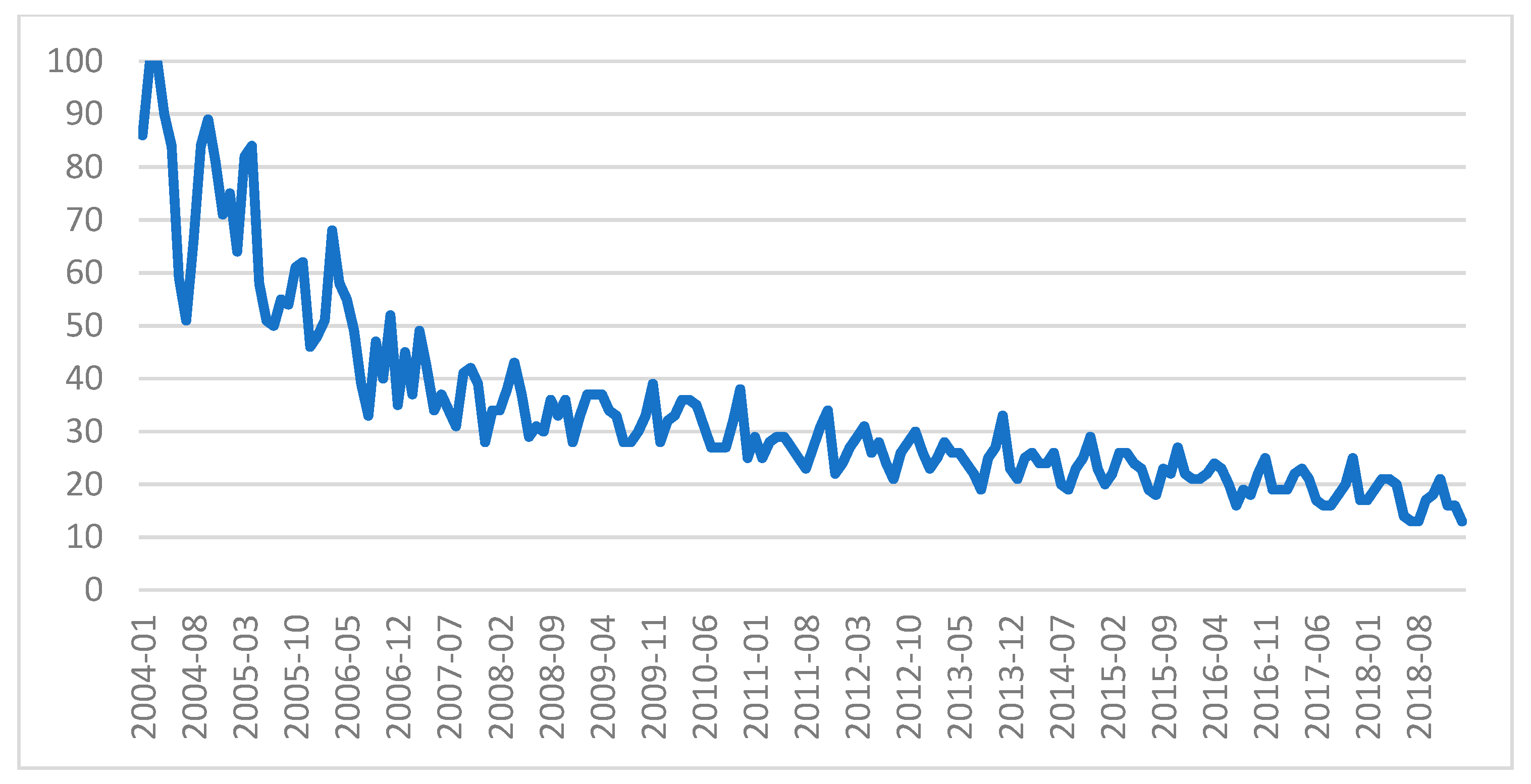

6.1. Search Interest

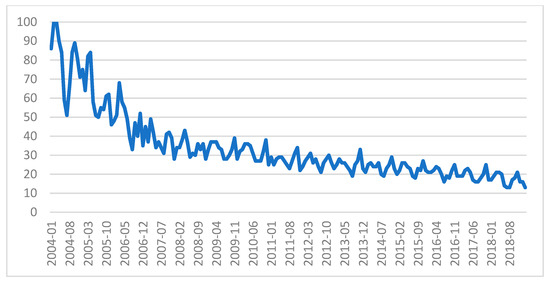

Google Trends (Choi and Varian 2012) is an analytical tool that can be used to monitor and measure the interest in different search terms in the period from 2004 until the present time. In previous research, it has been suggested that this tool may be able to provide some insight into the interest in and salience of management concepts and ideas such as TQM (Madsen 2016). As Figure 3 shows, the peak interest in TQM was in 2004, and since then, the level of interest has been on a steady downward trajectory. The decrease could be explained in different ways. One explanation is that the concept is perceived as old and not as “innovative” as new concepts such as Big Data Analytics and Agile Management, which in the last few years have enjoyed a sharp upswing in popularity (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018). Another possible reason for the decrease in search activity could be that TQM has become an accepted and entrenched part of the business vocabulary (Cedrola 2015; Dahlgaard-Park 2015; Hindle 2008) and that there is less need to “Google” what TQM is.

Figure 3.

Data source: www.google.com/trends, retrieved 5 February 2019.

6.2. Adoption and Diffusion

Detailed overviews of TQM adoption and diffusion are relatively hard to come by. A general problem is that many of the studies of TQM adoption and diffusion have been carried at different times, using different research methods and sample sizes, which makes comparison difficult.

Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b) cite a study by McKinsey & Company (1989) which found that there was strong and enthusiastic support for quality initiatives among executives. Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b, p. 1) also cite other studies reporting that about three-quarters of companies in the US and the UK have quality initiatives. Osterman (1994, 2000) and Lawler et al. (2001) provided some evidence showing that TQM continued to be widely implemented throughout the 1990s. Gibson et al. (2003) documented that managers had a high degree of knowledge and familiarity with the TQM concept. A survey carried out in Norway showed that most respondents had not adopted and implemented TQM to a large extent and had a long way to go (Sun 1999). In a recent study from Ethiopia, Addis (2019) notes that TQM is a relatively new concept, but finds that it is now used at a moderate level.

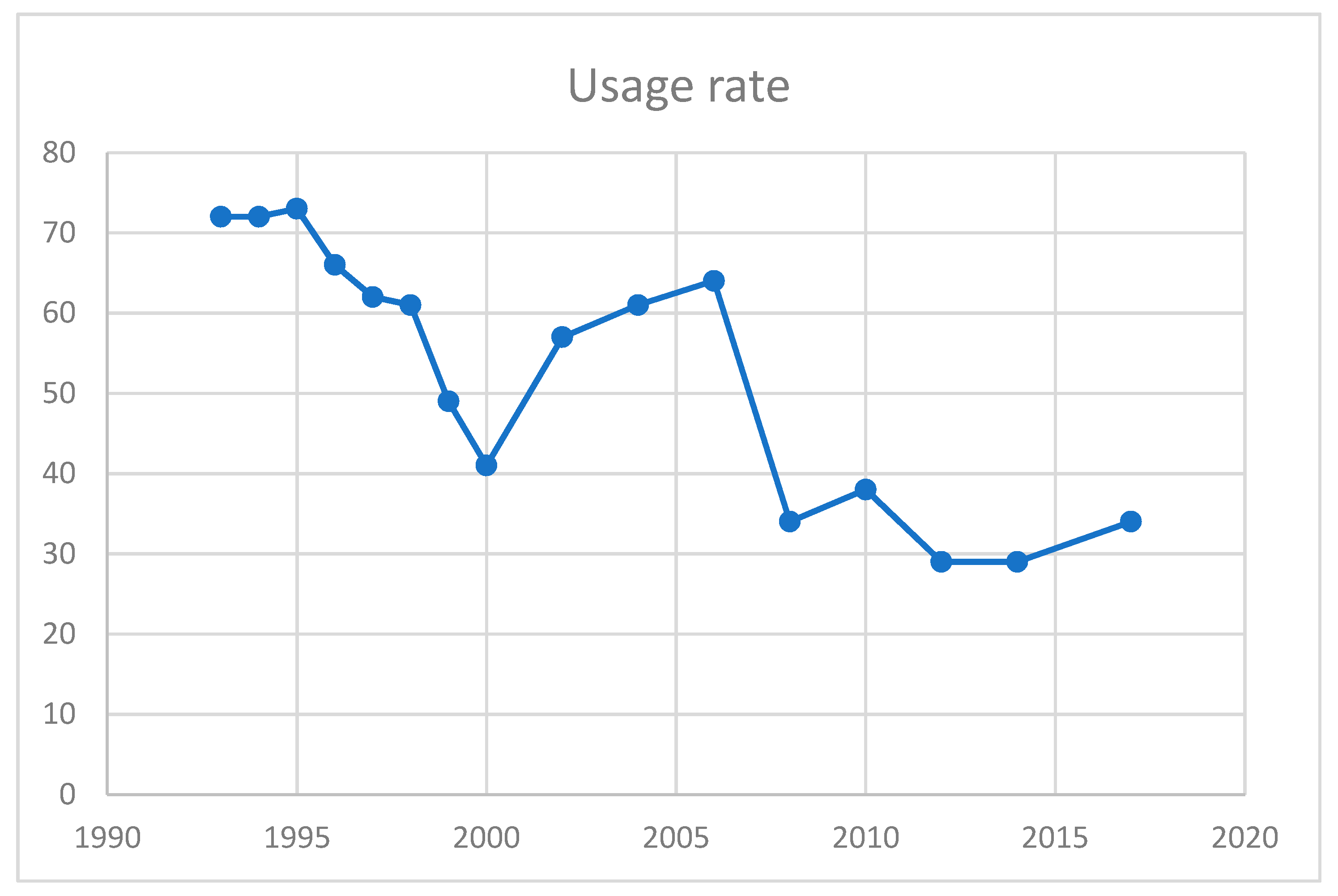

Bain & Company’s biannual “Management Tools and Trends” survey can be used to obtain a longitudinal overview of TQM’s worldwide popularity. An advantage in the case of TQM is that the concept has been part of this survey since its inception more than 25 years ago.

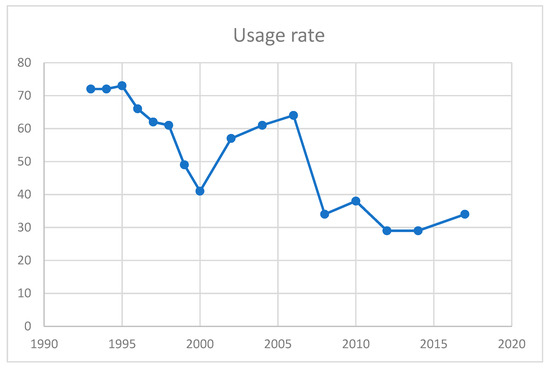

Figure 4 shows that the adoption rate was very high during the early to mid-1990s before it started falling towards the late 1990s. Although there was a resurgence during the first half of the 2000s, the usage rate started falling again during the late 2000s and has stabilized at around 30 percent in recent years. It should be noted that Figure 4 shows the usage rate percentage, and while there is a clear downward trend in terms of the percentage of companies who use TQM, there has been a general decline in the usage of management tools, according to Bain & Company’s survey (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018). This means that the usage ranking of TQM has increased even though the absolute number of users has decreased.

Figure 4.

Usage rate (Source: Bain & Company’s surveys 1993–2017).

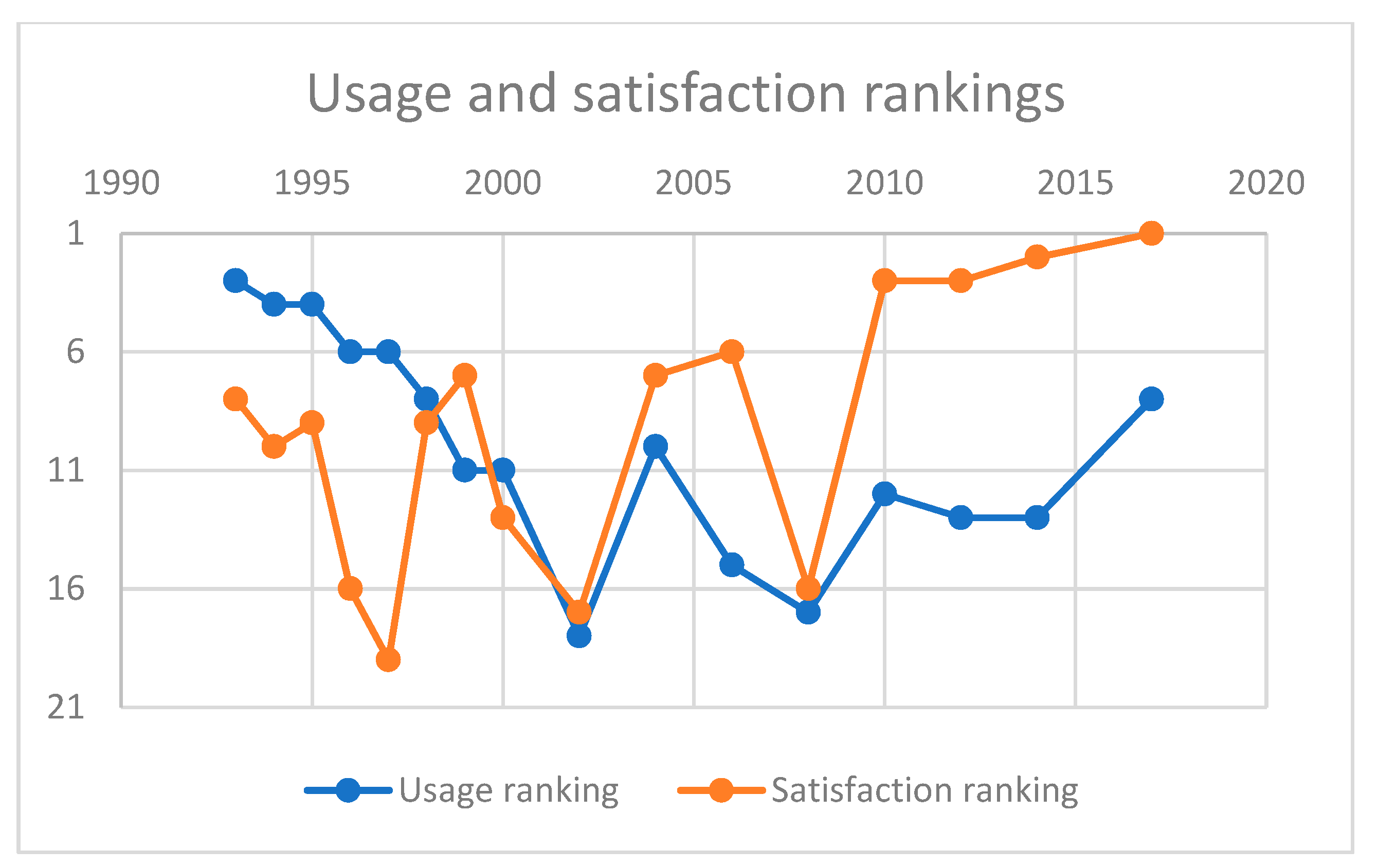

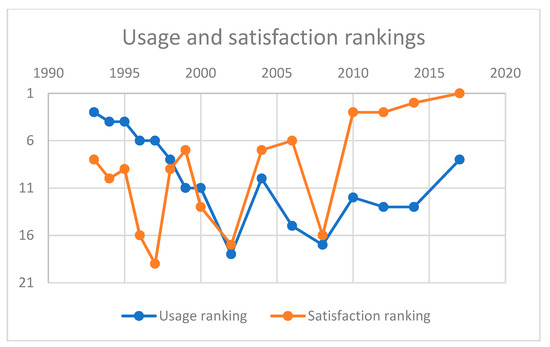

Figure 5 provides an overview of the usage and satisfaction ranking over the period 1993-2017. The figure shows that the use of TQM ranked among the top 5 in the 1990s. At the same time, it can be observed that the concept’s position has slipped a little in recent years. However, TQM is still among the top 15 and has climbed to eighth place in the most recent survey (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018). The satisfaction ranking has been on an upward trajectory in recent years and has hovered around the top three before reaching first place in 2017. What could explain that an “old-school” concept such as TQM is associated with such high levels of satisfaction? A possible explanation could be that organizations are better able to avoid the pitfalls now that TQM has become a more well-established concept and is less subject to hyping and inflated expectations.

Figure 5.

Usage and satisfaction rankings (Source: Bain & Company’s surveys 1993–2017).

While Figure 5 illustrates the trajectory in terms of the global usage rate, other researchers have noted that there has been a shift in the relative popularity of TQM across geographical regions. In the West, TQM has been on a downward trajectory and has been overtaken by other concepts and ideas. In Eastern Europe and other emerging economies, there is currently much activity concerning TQM (Dahlgaard-Park 2015).

6.3. Implementation

As was noted in Section 4.3, TQM is a management concept that can be interpreted and implemented in many different ways. Westphal et al. (1997) found that early adopters tended to customize TQM to their organization. In contrast, later adopters tended to imitate others and conform to what was considered appropriate ways to use the concept. There also appears to be differences in terms of how firms of different sizes implement TQM. Sun and Cheng (2002) found that small and medium-sized firms focus more on the informal and people-oriented aspects, while larger firms focus more on the structured, organized, and process-oriented aspects of TQM. This finding may not be surprising since larger firms typically have access to more time and resources, which can be invested to improve structures and processes. Moreover, they tend to possess advanced IT systems that can be used to support TQM.

Research has also found that there is considerable variation when it comes to the level of TQM implementation (Dale and Lascelles 1997). An alternative way to look at TQM implementation is to think of “stages of quality culture” (Sandholm 1999) and what it takes for an organization to mature in its quality thinking and practices. Hill and Wilkinson (1995, p. 10) note that “companies seem to pick up bits and pieces of TQM and then report that they are operating TQM when in reality most schemes appear an ill-matched mixture of quality circles, employee involvement, quality tools and long established quality assurance systems.” In practice, TQM manifests itself in different ways (Webb 1995, p. 122).

As a whole, these findings suggest that, while the TQM concept has persisted (Venkateswarlu and Nilakant 2005), there is much variation in terms of implementation patterns. Therefore, it is still, to a large extent an open question precisely what parts of the TQM concept have persisted in practice (Bernardino et al. 2016).

6.4. Expectations and Effects

There has been much discussion of whether TQM leads to increased financial performance. During the heydays of the 1980s and early 1990s, expectations were very high, in particular in organizational practice. It has been noted that TQM implementations generally have struggled to deliver the financial performance improvements that users were hoping for and that these disappointing results have led to disillusionment (Hendricks and Singhal 1999). Some of the reasons for disillusionment could be due to the very upbeat rhetoric about TQM during the early period, which led to overly optimistic expectations concerning the effects of TQM (Zbaracki 1998). Staw and Epstein (2000) found that some managers adopted TQM to increase legitimacy and were driven more by bandwagon pressures.

Academic researchers have disagreed when it comes to the question of whether TQM affects financial performance. Easton and Jarrell (1998) found a relationship between the use of TQM and performance, particularly among the firms that use a more advanced form of TQM. Powell (1995) found that it was not the techniques and tools associated with TQM that give firms a competitive advantage; rather, it is the “softer” organizational and behavioral changes in the aftermath of a thorough TQM process that may be the source of competitive advantage. Examples of such changes include a more open organizational culture, employee involvement, and managerial focus. These effects may be hard to imitate, while tools and techniques to a greater extent can be copied or bought in the marketplace (cf. Barney 1991).

The mixed results have also led to a discussion about whether TQM is a flawed management idea (i.e., there is something wrong with TQM as a concept) or if it instead is implemented wrongly (Wilkinson and Willmott 1996). Defenders of TQM tend to argue that the lack of success is due to the way TQM is implemented and that there is not something inherently wrong with the concept (Evans 1995; Sørhaug 2016). As a consequence of the many failures reported in practice, authors have sought to identify common mistakes made in TQM implementation projects. For example, it is commonly argued that it is important to learn from failures (Macdonald 1995) and to identify the reasons why TQM does not work (Harari 1993). Moreover, it is important to understand possible reasons for disappointment (Macdonald 1996) and failure (Asif et al. 2009; Mohammad Mosadeghrad 2014).

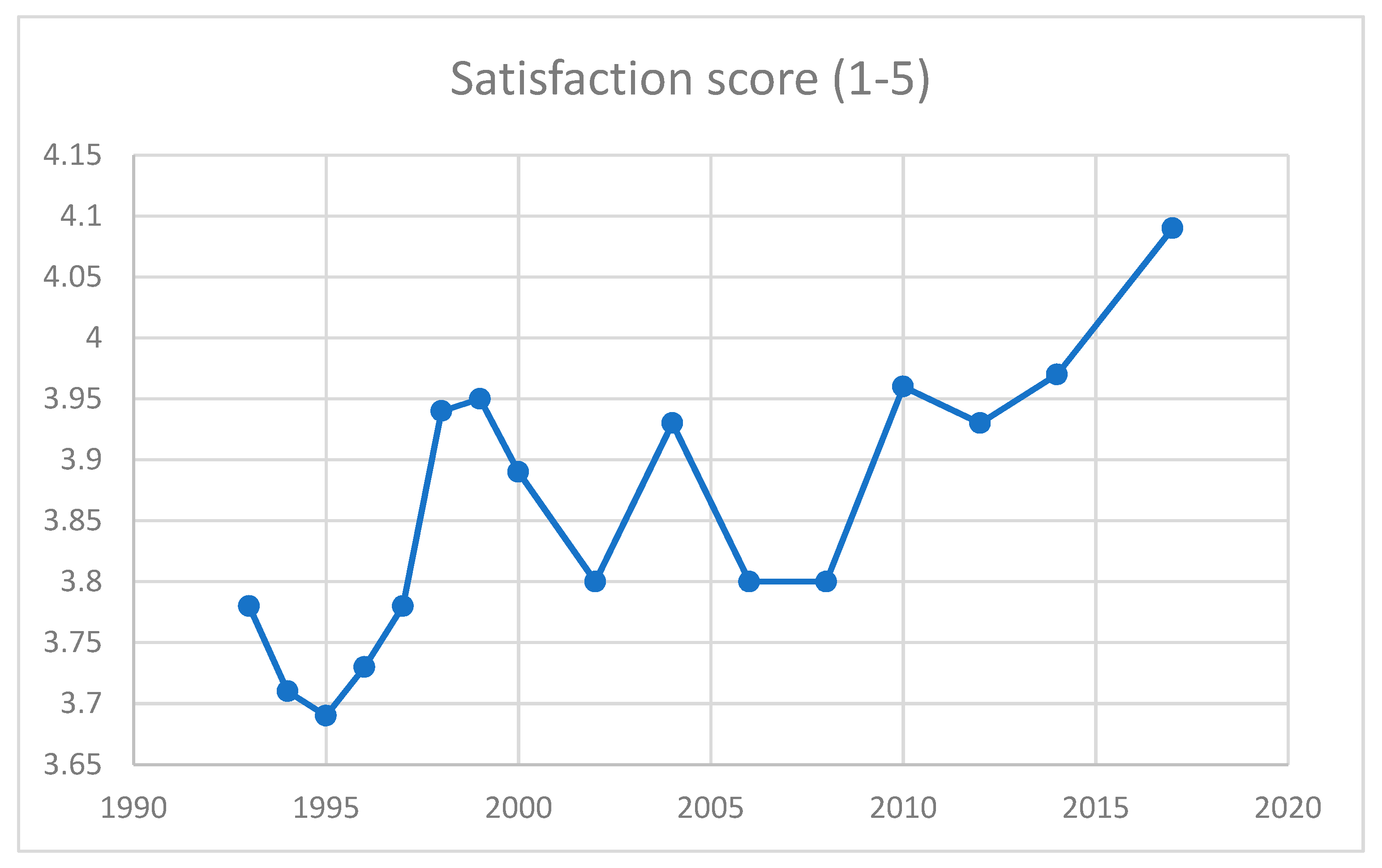

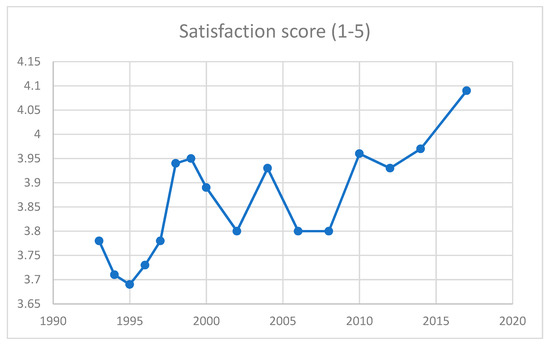

Figure 6 shows that the average satisfaction score has remained relatively stable, but also that it has been on a slight upward trajectory in recent years. Rigby and Bilodeau (2018, p. 5) note that “Total Quality Management’s systematic approach to quality improvement earns the highest satisfaction rates, including particularly strong reviews in China and India.”

Figure 6.

Satisfaction score (Source: Bain & Company’s surveys 1993–2017).

7. Discussion

7.1. Emergence

The historical review has shown that the emergence of TQM to a large part was driven by quality gurus such as Deming, Juran, and Crosby. The passivity of academics during the early phase created a vacuum and an opening for these gurus to establish themselves as authorities and thought leaders (Wilkinson and Willmott 1996). Over time, the strong position of the quality gurus also shaped the TQM literature and discourse and gave it a distinct “guru flavor.” During the 1980s and 1990s, a wide range of fashion-setting actors (e.g., consultants, trainers, conference organizers, book authors, business journalists) threw their hats into the ring and generated a “wave of interest” surrounding quality.

Another important driver of the emergence of TQM was the formation of an elaborate organizational infrastructure (e.g., organizations and institutes) which disseminated information and knowledge about quality thinking in the post WW2 era. This organizational infrastructure supporting quality thinking (cf. e.g., Benders et al. 2019; Perkmann and Spicer 2008) has been important in sustaining the interest in quality even in the face of various criticisms and problems. Perkmann and Spicer (2008) describe the various types of supporting activities carried out by proponents of the quality movement (e.g., standard-setting, awards, development of professional identities), which has helped institutionalize TQM and make it a more permanent practice (Perkmann and Spicer 2008). The varied evidence reviewed in Section 4 shows many examples of activities performed by suppliers of TQM.

7.2. Current Status

During the 1990s, the TQM concept started to face strong headwinds. TQM generally failed to live up to the overly high expectations among adopters, and academics and other skeptics started to question the lofty promises and the TQM concept’s overall merits. During the 1990s, the concept faced strong competition in the market for management knowledge, as several competing management concept movements tried to establish themselves, e.g., Business Process Reengineering (BPR), Benchmarking, Lean, and Balanced Scorecard, to name just a few. As Wilkinson and Willmott (1995b, p. 9) noted, TQM came under attack from “those peddling new panaceas” such as BPR, which criticized TQM as being an incremental as opposed to a radical “big bang” approach to organizational change.

Moreover, during this time, several competing and to some extent, related and complementary concepts were introduced and popularized in the management knowledge market. For example, Six Sigma is an example of a related concept (Goeke and Offodile 2005; Sabet et al. 2016), which Green (2006) argues breathed new life into TQM and contributed to a revival of TQM through the use of “fresh” and non-contaminated labels (cf. Benders and Van Veen 2001).

In recent years, there have been some developments that suggest that the TQM label has gone out of fashion and that it has been toned down. For example, it has been observed that the wording of the quality awards has been changed slightly (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). Another example suggesting that the word “quality” is not as popular as it used to be is the fact that the EFQM Model has been changed to the “European Model for Business Excellence” (Dahlgaard-Park 2015).

Despite the criticism and strong competition from other management concept movements, the TQM concept has not disappeared and is still impacting both discourse and practice (Bergquist 2012; Douglas 2006; Sower et al. 2016). Some researchers have documented that there has been a resurgence in the interest in TQM (Rahman 2004, Williams et al. 2004). During the mid-2000s, Ehigie and McAndrew (2005) noted that the adoption and diffusion of TQM was on the rise globally. While it may be on a downward trajectory in the West, there are signs it may be on the rise in other parts of the world (Dahlgaard-Park 2015). For example, the TQM concept is widely diffused in countries such as China (Huang et al. 2016) and Turkey (Özen and Berkman 2007).

7.3. Possible Future Trajectory

Lastly, the discussion will focus on TQM’s future trajectory, similar to what others have done in the past (e.g., Brown 2013; Harris 1995). The historical review in this paper has shown that the TQM concept has roots that go back decades, and in a life cycle perspective, the TQM concept reached old age already during the early 2000s (Larsen 2001). TQM no longer receives the level of attention in public management discourse that it did in the early phase of its life cycle. Dahlgaard-Park (2015) argues that other buzzwords such as Six Sigma, Lean, and Business/Organizational Excellence have taken TQM’s place in public management discourse. Jung and Kieser (2012, p. 329) define management fashions as those “management concepts that relatively speedily gain large shares in the public management discourse.” Following this definition, it can be argued that the TQM concept is no longer a management fashion.

At the same time, the evidence indicates that TQM is still alive and that the concept has persisted despite criticism, backlash, and stiff competition from a multitude of newer management concepts. It is interesting to observe that a concept from the “boomer generation” of management concept is still ranked in the top 10 of management concepts and tools (Rigby and Bilodeau 2018).

8. Conclusions

8.1. Concluding Comments

The current paper has aimed to reexamine the historical popularity trajectory of TQM. As noted at the outset, there is a multitude of conflicting viewpoints on the trajectory of TQM in the literature. By synthesizing and reconciling the findings of the vast literature on TQM, this paper provides an updated status report and a longitudinal overview of the trajectory of TQM from its inception up until today.

While the current paper is certainly not the first to view TQM through the lens of management fashion, it differs from previous papers by taking an integrative view of TQM from both a supply side and a demand side perspective. This arguably provides a more balanced account of TQM’s historical popularity trajectory. A study focusing solely on TQM from a supply side perspective would easily conclude that the concept is on life support since it no longer occupies a central place in public management discourse. When looking at the demand-side, however, the picture becomes more nuanced, as several sources show that TQM is still alive on the demand side. This finding is interesting in the context of the debate of the coevolution between public management discourse and organizational uptake of management fashions (Abrahamson and Fairchild 1999; Clark 2004; Nijholt and Benders 2007). It suggests that once-fashionable concepts such as TQM may stick around for a very long time in organizational practice (Heusinkveld and Benders 2012a; Perkmann and Spicer 2008).

8.2. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

The current paper has several shortcomings, which should be considered carefully. Due to the various challenges associated with researching management concepts and ideas (Madsen and Stenheim 2013; Strang and Wittrock 2019), it has been necessary to make several pragmatic methodological choices.

The current paper has aimed to provide a birds-eye view of the historical popularity trajectory of TQM. It has not been possible to fully take into account the viewpoints of all the actors involved or to chronicle all the events that have taken place in the history of TQM. Instead, the picture that emerges can be considered a “mosaic” (Morrison and Wensley 1991) or “overall picture” (Nijholt and Benders 2007). The paper is also limited by its heavy reliance on secondary sources (Nijholt and Benders 2007), which have been gathered at different times, using different research methods and sample sizes. Lastly, the analysis is also a little skewed towards data about supply side activity around TQM. As discussed in Section 6, it is relatively hard to find suitable and reliable data about the use of TQM among organizations on the demand side.

The various limitations open up several possibilities for future research. Instead of retrospectively reconstructing an overall picture of the trajectory of TQM, in the future, researchers could follow and trace the trajectory of TQM in real-time. Since the field of TQM is not as fast-moving as it was during the boom period of the 1980s and 1990s, it is now easier to obtain and maintain an overview of the key players and their activities.

Another possibility would be to zoom in on the diffusion and implementation of TQM in different regional or national contexts. In the current study, the focus has been on the popularity of TQM at the international level. However, the popularity trajectory of TQM is likely to diverge as the concept is diffused and translated in different local settings, and the so-called “national reception patterns” (Benders and Van Bijsterveld 2000) of TQM may vary. The findings of this paper indicate that while TQM is on the decline in the West, it is on the rise in emerging and developing countries (Addis 2019; Dahlgaard-Park 2015; Isaksson et al. 2016). A cross-country study of the diffusion of TQM could shed more light on how the trajectory of the concept varies across time and space.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of South-Eastern Norway’s Open Access Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abrahamson, Eric, and A. Reuben. 2014. The Business Techniques Market Hypothesis. New York: Columbia Business School, p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, Eric. 1996. Management Fashion. Academy of Management Review 21: 254–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, Eric, and Gregory Fairchild. 1999. Management fashion: Lifecycles, triggers, and collective learning processes. Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 708–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, Eric, and Alessandro Piazza. 2019. The Lifecycle of Management Ideas. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 42–67. [Google Scholar]

- Addis, Sisay. 2019. An exploration of quality management practices in the manufacturing industry of Ethiopia. The TQM Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, Karl. 1992a. The last days of TQM? Quality Digest 12: 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, Karl. 1992b. No eulogies for TQM. The TQM Magazine 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Roy, Henrik Eriksson, and Håkan Torstensson. 2006. Similarities and differences between TQM, six sigma and lean. The TQM Magazine 18: 282–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, Jiju. 2013. What does the future hold for quality professionals in organisations of the twenty-first century? The TQM Journal 25: 677–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Muhammad, Erik Joost de Bruijn, Alex Douglas, and Olaf AM Fisscher. 2009. Why quality management programs fail. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 26: 778–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, John. 1992. The Essence of Total Quality Management. Hertfordshire: Prentice Hall Hemel Hempstead. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Marcos, and Charles-Clemens Rüling. 2019. Business Media. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bendell, Tony, Roger Penson, and Samantha Carr. 1995. The quality gurus—Their approaches described and considered. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 5: 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos, Marlieke Van Grinsven, and Jonas Ingvaldsen. 2000. Leaning on lean: The reception of management fashion in Germany. New Technology, Work and Employment 15: 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos, and Marlieke Van Veen. 2001. What’s in a Fashion? Interpretative Viability and Management Fashions. Organization 8: 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benders, Jos, and Sander Verlaar. 2003. Lifting parts: Putting conceptual insights into practice. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 23: 757–74. [Google Scholar]

- Benders, Jos, Marlieke Van Grinsven, and Jonas Ingvaldsen. 2019. The persistence of management ideas; How framing keeps lean moving. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon, Estela Mara. 1995. Total quality management in the academy: A rebellious reading. Harvard Educational Review 65: 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, Bjarne, Maria Fredriksson, and Magnus Svensson. 2005. TQM: Terrific quality marvel or tragic quality malpractice? The TQM Magazine 17: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, Bjarne, Kevin Foley, Rickard Garvare, and Peter Johansson. 2008. Reframing quality management. In The Theories and Practices of Organization Excellence: New Perspectives. Sydney: SAI Global, p. 501. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist, B. 2012. Alive and kicking–but will Quality Management be around tomorrow? A Swedish academia perspective. Quality Innovation Prosperity 16: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berman, Evan M. 1995. Implementing TQM in state welfare agencies. Administration in Social Work 19: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, Lis Lisboa, Francisco Teixeira, Abel Ribeiro de Jesus, Ava Barbosa, Maurício Lordelo, and Herman Augusto Lepikson. 2016. After 20 years, what has remained of TQM? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 65: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaden, Ruth J. 1996. Is total quality management really unique? Total Quality Management 7: 553–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaden, Ruth J. 1997. What is total quality management … and does it matter? Total Quality Management 8: 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohan, George. 1998. Whatever happened to TQM? Or, how a good strategy got a bad reputation. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 17: 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohoris, George A. 1995. A comparative assessment of some major quality awards. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 12: 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann, Lutz, and Rüdiger Mutz. 2015. Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66: 2215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bort, Suleika. 2015. Turning a management innovation into a management panacea: Management ideas, concepts, fashions, practices and theoretical concepts. In Handbook of Research on Management Ideas and Panaceas: Adaptation and Context. Edited by Anders Örtenblad. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. 2013. Quality: Where have we come from and what can we expect? The TQM Journal 25: 585–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, John A. 1997. Management theory-or fad of the month. Business Week 129: 47. [Google Scholar]

- Carnerud, Daniel. 2018. 25 years of quality management research—Outlines and trends. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 35: 208–31. [Google Scholar]

- Carnerud, Daniel. 2019. The quality movements three operational paradigms-A text mining venture. The TQM Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnerud, Daniel, and Ingela Bäckström. 2019. Four decades of research on quality: Summarising, Trendspotting and looking ahead. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchick Miguel, Paolo A. 2001. Comparing the Brazilian national quality award with some of the major prizes. The TQM Magazine 13: 260–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrola, Elena. 2015. Total Quality Management. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Hyunyoung, and Hal Varian. 2012. Predicting the present with google trends. Economic Record 88: 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Timothy. 2004. The fashion of management fashion: A surge too far? Organization 11: 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluley, Robert. 2013. What Makes a Management Buzzword Buzz? Organization Studies 34: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Robert E. 1992. The quality revolution. Production and Operations Management 1: 118–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Robert E. 1998. Learning from the quality movement: What did and didn’t happen and why? California Management Review 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Robert E. 1999. Managing Quality Fads: How American Business Learned to Play the Quality Game. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Robert E, and W Richard Scott. 2000. The Quality Movement & Organization Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, David. 2000. Management Fads and Buzzwords. Critical-Practical Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, David. 2019. Management’s Gurus. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, Tito A. 2007. A history and review of the European Quality Award Model. The TQM Magazine 19: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, David, and Weiyong Zhang. 2019. The Baldrige Award’s falling fortunes. Benchmarking: An International Journal 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cua, Kristy O, Kathleen E McKone, and Roger G Schroeder. 2001. Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management 19: 675–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgaard-Park, Su Mi. 2011. The quality movement: Where are you going? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 22: 493–516. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgaard-Park, Su Mi. 2015. Total Quality Management (TQM). In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy. Edited by Su Mi Dahlgaard-Park. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 808–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, Barrie G, and Cary L Cooper. 1992. Total Quality and Human Resources: An Executive Guide. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, Barrie G, and David M Lascelles. 1997. Total quality management adoption: Revisiting the levels. The TQM Magazine 9: 418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R. J., and D. Strang. 2006. When fashion is fleeting: Transitory collective beliefs and the dynamics of TQM consulting. Academy of Management Journal 49: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Patrick, and Gill Palmer. 1993. Total quality management in Australian and New Zealand companies: Some emerging themes and issues. International Journal of Employment Studies 1: 115. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Alex. 2006. TQM is alive and well. The TQM Magazine 18: null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Alex. 2007. Where next for the quality movement? The TQM Magazine 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Alex. 2013. 25 years of the TQM Journal. The TQM Journal 25: null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Kevin. 1992. Who’s killing total quality? Incentive 166: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, Helga. 1992. The Quality Movement: What Total Quality Management is Really all About! London: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, George S., and Sherry L. Jarrell. 1998. The Effects of Total Quality Management on Corporate Performance: An Empirical Investigation. The Journal of Business 71: 253–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehigie, Benjamin Osayawe, and Elizabeth B McAndrew. 2005. Innovation, diffusion and adoption of total quality management (TQM). Management Decision 43: 925–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwall, Lars, and Linda Wedlin. 2019. Business Studies and Management Ideas. In Oxford Handbook of Management Ideas. Edited by Andrew Sturdy, Stefan Heusinkveld, Trish Reay and David Strang. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Rob. 1995. In defence of TQM. The TQM Magazine 7: 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felizardo, Katia Romero, Emilia Mendes, Marcos Kalinowski, Érica Ferreira Souza, and Nandamudi L Vijaykumar. 2016. Using forward snowballing to update systematic reviews in software engineering. Paper presented at the 10th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measuremen, Ciudad Real, Spain, September 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, Maria, and Raine Isaksson. 2018. Making sense of quality philosophies. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 29: 1452–65. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, David A. 1988. Managing Quality: The Strategic and Competitive Edge. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobadian, Abby, and Simon Speller. 1994. Gurus of quality: A framework for comparison. Total Quality Management 5: 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccio, M., M. Canfora, and A. Del Signore. 2013. The first theorisation of quality: Deutscher Werkbund. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 24: 225–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Jane Whitney, and Dana V Tesone. 2001. Management fads: Emergence, evolution, and Implications for managers. The Academy of Management Executive 15: 122–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Jane Whitney, Dana V Teson, and Charles W Blackwell. 2003. Management fads: Here yesterday, gone today? SAM Advanced Management Journal 68: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, Helene, and Sylvain Landry. 1998. Schools of thought in and against total quality. Journal of Managerial Issues 10: 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, Helene, and James R Taylor. 2002. The justification of knowledge: Tracking the translations of quality. Management Learning 33: 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, Helene. 2006. ‘It was such a handy term’: Management fashions and pragmatic ambiguity. Journal of Management Studies 43: 1227–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeke, Richard J, and O Felix Offodile. 2005. Forecasting management philosophy life cycles: A comparative study of Six Sigma and TQM. The Quality Management Journal 12: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Forrest B. 2006. Six-Sigma and the revival of TQM. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 17: 1281–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grint, Keith. 1997. TQM, BPR, JIT, BSCs and TLAs: Managerial waves or drownings? Management Decision 35: 731–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J Richard, and Ruth Wageman. 1995. Total quality management: Empirical, conceptual, and practical issues. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 309–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, Oren. 1993. Ten reasons why TQM doesn’t work. Management Review 82: 33. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, Robert R, and Greg Laird. 1997. Linking marketing strategy to customer value: Implications for technology marketers. Paper presented at the Innovation in Technology Management-The Key to Global Leadership. PICMET’97: Portland International Conference on Management and Technology, Portland, OR, USA, July 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C. R. 1995. The evolution of quality management: An overview of the TQM literature. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration 12: 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Lee. 1995. Beyond TQM. Quality in Higher Education 1: 123–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, Kevin B, and Vinod R Singhal. 1999. Don’t count TQM out. Quality Progress 32: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Hensler, Douglas. 2004. Why is it difficult to succeed with quality improvements? Measuring Business Excellence 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, Iñaki, Erlantz Allur, and Iker Laskurain. 2013. The Dissemination of the TQM Paradigm: A Preliminary Study Based on Scholar Citation and General Trend Counts. In Shedding Light on TQM: Some Research Findings. Bilbao: University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU—Press Service, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld, Stefan. 2004. Surges and Sediments. Organization Concepts between Transience and Continuity. Nijmegen: University of Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld, Stefan, and Jos Benders. 2012a. Consultants and organization concepts. In The Oxford Handbook of Management Consulting. Edited by M. Kipping and T. Clark. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- Heusinkveld, Stefan, and Jos Benders. 2012b. On sedimentation in management fashion: An institutional perspective. Journal of Organizational Change Management 25: 121–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heusinkveld, Stefan. 2013. The Management Idea Factory: Innovation and Commodification in Management Consulting. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Stephen. 1995. From quality circles to total quality management. In Making Quality Critical: New Perspectives on Organizational Change. Edited by Adrian Wilkinson and Hugh Willmott. London: Routledge, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Stephen, and Adrian Wilkinson. 1995. In search of TQM. Employee Relations 17: 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindle, T. 2008. Guide to Management Ideas and Gurus. London: The Economist in Assocation with Profile Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xiaoqian, Danyang Gao, and Meijuan Wang. 2016. Management Innovation in Chinese Context: The Diffusion of TQM in China. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 6: 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huczynski, Andrzej. 1993. Management Gurus: What Makes Them and How to Become One. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huczynski, Andrzej A. 1992. Management Guru Ideas and the 12 Secrets of their Success. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 13: 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Robert A. 1995. On the road to quality, watch out for the bumps. The Journal for Quality and Participation 18: 24. [Google Scholar]