1. Introduction

Romania failed to collect thirty-nine percent of its projected value added tax (VAT) revenue in 2015, according to Ziarul financiar (18 February 2019), who cites MEDIAFAX, and a rapport of the European Commission. Although this figure is down from thirty-eight percent in 2014, Romania remains the European Union country with the largest VAT collection deficit, ahead of Slovakia (twenty-nine percent) and Greece (twenty-eight percent). In 2013, tax evasion amounted to sixteen percent of GNP (about twenty-two billion dollars), up from nine percent in 2000 (

Ilie 2014). Other mass media outlets and Romanian academics alike cite these figures multiple times.

The figures, however, are not earth-shattering. Romania is not the only offender when it comes to tax evasion and/or the informal economy. Nor is it the worst offender. There are other European countries, such as Slovakia, Malta, Lithuania, Greece, and Italy, whose names make the headlines and who also have a significant informal economy, in the neighborhood of twenty- to twenty-two percent of the GDP (

The Local 2016). The informal economy, also known as the shadow economy, represents a part of the economy outside the reach of the government: it is not monitored, regulated, and most importantly, it is not taxed (

Ianole-Călin et al. 2017).

The reporting of these statistics is not necessarily a momentous revelation, if it were not for its ominous tone that puts the story in the context of a broader, apocalyptic fresco. Apocalyptic media coverage is not something new, nor is it something afflicting Romania alone.

In Romania, more than anywhere else, the level of collective outrage over the political and economic performance of the government seems to be maintained at a pitch fever level. In the end, it does not matter much whether this signals the involvement of the media in the political process, or if it merely represents a cultural phenomenon: the emerging picture is one of dismal government competence and tax evasion spinning out of control. The more important question, however, seems to be whether the reporting is indicative of the true perceptions and attitude Romanians have towards the informal economy; and towards evading and avoiding taxes.

This particular issue is highly relevant, given the challenges faced by all Eastern European countries in managing tax reform, in order to modernize their public sector and boost the economy (

Wyslocka and Tatsiana 2016;

Ślusarczyk 2018;

Tsindeliani et al. 2019). There are still significant economic and social differences between the former communist countries of Eastern Europe and the rest of the European Union, and Romania does not compare very favorably in this context. One would also expect that there are differences among Eastern European countries themselves, based on their unique culture and history. There are, however, shared elements, owing to the geography and political history of the region. At stake is the consolidation of a public system based on trust and efficiency that would allow further integration and harmonization with the rest of Europe.

We set out to investigate the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the informal economy and its determinants in the context of post-communist Romania. Our research question leads to a three-pronged approach. First, what is the true perception of state capacity and tax evasion? We believe that the perception of state capacity has an important role to play because it signals the extent to which the state is able and willing to honor an implicit social contract to deliver the public goods that are commensurate with tax collection; and it shows the extent to which the state is truly capable of imposing significant penalties on those who are bent on evading taxation (

Alm et al. 1992;

Feld and Frey 2007). In a first step, we attempt to measure the perception of state capacity and the perception of tax evasion. We use these results as explanatory variables of the general level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy.

In the second step, we measure the general level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy in Romania. The media depicts rampant tax evasion, but common sense suggests that this coverage could be biased. Our attempt to survey individual attitudes towards tax evasion and the informal economy in a systematic manner clarifies the issue.

In a third and final step, we investigate the factors that influence the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the informal economy. We posit that the perception of state capacity and tax evasion must be an important determinant, but clearly it is not the only one. Individual attitudes toward tax compliance and the informal economy are shaped by a complex set of factors that are influencing each other. Individual psychological traits represent the core mechanism that underpins individual behavior (

Wenzel 2005;

Feld and Frey 2007;

Wenzel 2004). Individuals develop their own world-view and attitudes informed by beliefs about social justice and the perception of social norms and practices (

Richardson 2008;

Tyler 1990).

We make two specific contributions in this paper. We survey attitudes towards tax compliance and its determinants in Romania, something that no other scholars have done, to our knowledge. We also focus on the perception of state capacity with its direct and mediated impact on the tolerance to tax evasion, using a Partial Least Square path modeling approach. Our research adds to the literature on tax evasion in general, and to that on tax evasion in post-communist Eastern Europe in particular, notwithstanding the institutional and cultural differences between Romania and the other post-communist neighbors. As almost all Eastern-European countries have embarked on programs aimed at reforming and improving their tax systems, it is critical to embrace the most appropriate strategy to increase the level of compliance, as explained next.

We use a questionnaire to survey 250 respondents, in order to estimate nine variables of interest (some of which are latent variables): five predictors, three mediators, and one outcome variable. The perception of state capacity, the extent to which tax evasion is considered a minor infraction, the extent to which tax evasion is considered socially unacceptable, the extent to which tax compliance is considered a civic duty, and the extent to which noncompliance is perceived as driven by a lack of distributive equity are predictor variables. The perception of noncompliance, the extent to which compliance is perceived to be driven by fear of penalties, the level of tolerance towards creative business and accounting practices aimed at evading taxation are mediating variables; and the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy is the outcome variable. We use gender and age as control variables. The nine variables of interest and the two control variables are part of a structural equation model estimated by a partial least square regression, using WarpPLS and R.

In the first stages of our investigation, we find that our respondents perceive the state as relatively weak and tax evasion as moderate. Noncompliance and the informal economy are perceived as driven by lack of distributive equity. Overall, it is considered that noncompliance is not a minor infraction, and is not socially acceptable. Compliance is perceived as a civic duty and the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy appears relatively low, but the sentiment is not as strong as expected.

Following the implementation of our PLS model, we find that the perception of state capacity is inversely related to the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy, but the direct relationship is not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with our expectations. The level of tolerance towards creative business and accounting practices aimed at evading taxation is the strongest predictor of the tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy, and has the largest effect size as well.

Among the more unexpected results, we find that the perception of tax evasion is inversely related to the level of tolerance towards noncompliance, and compliance driven by fear of penalties is in fact increasing the tolerance towards tax evasion. Three of the latent variables used in the model act as either partial, and in some cases total, mediators.

The results suggest that our respondents might be experiencing a self-enhancement bias when exposed to the relentless coverage of tax evasion and poor government performance portrayed in the mass media. We also conclude that, at least in Romania, where social capital is relatively lacking, the path to fostering social trust and citizenry is in promoting civic engagement. The government bureaucracy will arguably be more successful at shaping attitudes when using a softer touch, rather than the coercive power at its disposal.

The above findings are indeed intriguing, but one has to keep in mind that the study presented here is exploratory in nature. It relies on a sample that might appear small at first. Nevertheless, we employ a methodology that is largely non-parametric and can compensate for any potential selection bias and the relative smallness of the sample. For such an exploratory study, the PLS-PM methodology applied to 250 observations still delivers robust results, as long as one is aware of its limitations and refrains from sweeping generalizations. We hope that, in the future, as more data will become available, the scope of this type of investigation will be extended and additional evidence will corroborate the findings presented here.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section discusses state capacity and its relationship to tax compliance.

Section 3 discusses the importance of state capacity and how its perception can influence the level of tolerance towards tax evasion.

Section 4 discusses the role of social norms and the importance of individual beliefs about social justice and civic mindedness.

Section 5 presents the data and methodology.

Section 6 presents the results.

Section 7 attempts to interpret our empirical findings, and

Section 8 concludes.

2. A Question of State Capacity

State capacity matters, because taxation represents one of the fundamental functions of the state (

Tilly 1978). In general, one defines state capacity as the ability to concentrate power, in order to implement public policy and deliver public goods (

Mann 2012;

Rogers and Weller 2014).

The role of a capable state includes, but is not limited to: maintaining an exclusive monopoly on violence and coercion; reducing information asymmetry and constraining elites; redistributing income; and delivering public goods. Among the more important public goods, one counts the provision of national defense, the maintenance of law and order, the provision of education and healthcare, and the construction and maintenance of the infrastructure system (

Fukuyama 2014). State capacity is essential in creating the necessary conditions for enabling widespread social trust and collective action with a minimum of transaction costs.

Taxation—a core task of the state—is one of the ‘least likely’ dimensions of state capacity to decline (

Weyland 1998). By the time that the ability to collect taxes is impaired, other aspects of state capacity, such as the provision of infrastructure building and education, are already diminished.

The proportion of income tax revenue to total fiscal revenue is one of the most important metrics of state capacity, because it requires a very special mix of skilled enforcement and voluntary compliance from taxpayers (

Atkinson and Stiglitz 1976;

Soifer 2008). It is not hard to see that compliance is truly voluntary only when state authority is perceived as legitimate (

Fukuyama 2014). There are other forms of revenue collection that are important, but they do not demand the high level of state capacity required by income tax collection. Successful VAT collection—the hotly debated issue in the Romanian mass media—is not necessarily indicative of a highly capable state, because it requires little administrative effort and planning (

Bird and Zolt 2014;

Lieberman 2002).

On the other hand, a significant VAT collection deficit represents a strong indication of low state capacity, precisely because it is relatively easy to achieve. In Romania, the relationship between income tax and VAT makes for a very interesting dynamic. Marginal tax rate on individual income in Romania was lowered from sixteen percent to ten percent (

Trading Economics 2019), among the lowest in the world. This makes income tax evasion not worth pursuing with the same intensity, as is the case where the marginal tax rate on income stands at fifty percent. Relatively speaking, VAT dodging becomes more attractive when income tax is low. In the context of a large natural economy, a large informal market, and a relatively weak state, one ends up with a large VAT deficit.

A side question is whether the low marginal income tax rate represents an attempt to implement a bold supply-side fiscal policy, or simply an indication of a government who concedes it would never be able to enforce a higher and more stringent tax rate. If the latter is true, a low marginal tax rate on income leads to simply replacing one problem with another. This question, however, will not be pursued here, as it would be extremely difficult to discriminate between a programmatic fiscal policy and one driven by a desire to find a stop-gap solution.

In Romania, there is abundant anecdotal evidence suggesting that the state has a weak ability to build large infrastructure projects, such as highways, bridges, etc. In the heart of the capital city, Bucharest, there are thousands of buildings who sustained major structural damage in the wake of three major earthquakes that occurred between 1977 and 1991, yet several decades later, those buildings are still in a state of disrepair. The construction of major highways is lagging behind similar projects in other former communist bloc countries (

McGrath 2019;

The Economist 2011), and the relative cost of highway building is among the highest in Europe (

Romania Insider 2013).

The relative lack of state capacity, however, need not impact all dimensions equally. While in some respects, the state might be relatively weak, in others, it might be relatively strong. Any attempts to measure the perception of state capacity needs to capture as many dimensions as possible. However, the one measure that is consequential to our research is the ability to collect taxes.

Focusing on tax evasion in relation to state capacity is a highly relevant issue. Finding that the state is able to enforce taxation says little about other aspects of state capacity, as argued earlier. Finding that the state is not able to enforce taxation means that the state is most certainly not able to deliver healthcare, law and order, and education. A dismal perception of state capacity might embolden people to dodge their taxes. A weak state, unable to deliver on its end of the social bargain, would be met with contempt by taxpayers (

Alm et al. 1992). Citizens have no reasons to give their money to a government who does little to make their life better (

Feld and Frey 2007). Moreover, citizens have little to fear from a weak government—that is, a government not capable of enforcing its monopoly on coercion.

Following this line of argumentation, we expect that the perception of state capacity correlates well with the tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy. At the same time, we expect that the perception of a weak sate also correlates well with the perception of tax evasion.

3. Social Norms and Personal Beliefs

It has been shown that the level of tax compliance is too high when compared to the level of tax enforcement. Evaluating the cost-benefit dynamic of tax compliance reveals that rational individuals should pay far less tax and engage in more tax evasion then they actually do (

Alm et al. 1992). Fear of penalties alone is simply not enough to explain why people comply. The key to this riddle is recognizing that compliance is determined by a significant number of intrinsic drivers. The important factors shaping individual attitudes towards tax compliance and the informal economy are represented by personal beliefs and social norms (

Cullis and Lewis 1997;

Frey 1997;

Torgler 2005).

Social norms represent another powerful source of personal tax ethics. Individuals are norm-following creatures. Social and cultural norms are off-the-shelf heuristics for dealing with a majority of social interactions. One can easily argue that, at their core, they represent a reasonable approach to problem solving. Yet, norms become institutionalized and invested with emotional and intrinsic value. Individuals end up following them, not in pursuit of optimal social outcomes, but for their own sake (

Fukuyama 2014;

Cialdini et al. 1991).

Obeying the norms of society, including either paying or evading taxes, comes naturally, due to peer pressure, identification with the values of a group, or pure behavior emulation (

Wenzel 2004;

Mullen et al. 1992). Social norms have a distinct cross-cultural component. It matters where individuals have to pay their taxes (

Richardson 2008;

Torgler and Schneider 2007).

Romania has been in transition for almost three decades, and it witnessed a radical turn of events, in which a hyper-centralized, command economy has been replaced with cut-throat market competition. The expectations of individuals have switched from the straitjacket of the authoritarian system to the apparent haziness of the liberal economy. A sub-segment of our research question focuses on the extent to which compliance is perceived as a civic duty, the extent to which noncompliance is perceived as socially unacceptable, and the extent to which noncompliance is considered a minor infraction.

We also consider the level of tolerance towards business and accounting practices aimed at avoiding taxation. This variable is only one degree of separation removed from personal tax ethics, and might reveal the implicit beliefs that individuals hold with respect to the legitimacy of market competition and capitalism in general.

4. Data and Method

Our research investigates the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the shadow economy. We measure the perception of state capacity, perception of tax evasion, and several other variables—as described above—that are used in the framework of a PLS-SEM model as determinants of the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the shadow economy.

We surveyed 250 participants who answered a 2018 online questionnaire. There is a total of seventy questions grouped into nine categories: (i) control variables: age, gender, education, profession, etc.; (ii) perception of state capacity (STATE_C); (iii) the extent to which noncompliance is perceived as a minor infraction (MINOR); (iv) the extent to which compliance is perceived as a civic duty (CIVICDTY); (v) the extent to which noncompliance is perceived as driven by a lack of distributive equity (LackEqty); (vi) the extent to which tax evasion is perceived as not socially acceptable (NOTACPT), (vii) the perception of the extent of tax evasion (PERCEPNC) (viii), the extent to which compliance is driven by fear of penalties (FEAR_R); (xix) the level of tolerance towards business and accounting practices aimed at avoiding taxation (BUSINESS); (x) the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy.

There are 110 male and 140 female respondents, aged eighteen to over sixty years. Since 180 respondents are forty years and younger, there is a slight bias towards females and younger respondents. The socio-economic background of the respondents is quite diverse, including students, self-employed individuals, workers, and employees of small and large corporations. Data on gender and age are used as control variables. We are well aware that gender and age differences might impact attitudes towards compliance (

Vacca et al. 2020). The vast majority of questions in the survey are on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents a strong disagreement and 5 represents strong agreement.

The methodology for surveying the respondents and collecting the data, including the items used in the measurement, are taken from a survey on attitudes and behavior towards tax evasion and compliance implemented in Ireland in 2008/2009 by the Office of the Revenue Commissioners (the governmental structure responsible for tax administration and customs regime) (

Walsh 2012). This methodology has been implemented in Romania (

Druică et al. 2019). The questionnaire has been validated and its structure meets our needs.

Although self-selection bias is a legitimate concern, our analysis is exploratory in nature. The convenience sample is sufficient in size to allow for a sound analysis of the data, owing to the non-parametric nature of the methodology, as explained next. Potential selection-biases are dealt with by using bootstrapping, making for a robust methodology and results that are valid, even with small size samples. Sample statistics are presented in (

Supplementary Materials). The perception of noncompliance (PERCEPNC) appears moderate (Panel A); while some of the answers show a median of four, the means are barely above three, which represents the neutral level. This result does not appear to match the ominous pronouncements found in the mass-media on the subject of tax evasion. The strongest agreement is found when the respondents are asked whether there is a tax evasion culture. There is very weak support for the perception that tax evasion is up.

Respondents tend to disagree that tax evasion is a minor offense (MINOR), but not strongly (Panel B). The median equals two, but the average is slightly higher than two, relatively close to the neutral level.

There appears to be consensus that tax compliance is a civic duty (CIVICDTY), yet the sentiment that tax evasion is not socially acceptable (NOTACPT) is somewhat weaker (Panel C). The average response for the former is above four, and the median equals four. The average response for the latter is barely larger than three and the median is three. This apparent inconsistency might be due to the way in which the questions are framed; or, it might simply reflect inconsistencies in the beliefs of the respondents.

There are five questions pertaining to various aspects of state capacity (STATE_C) and the answers indicate that the state is perceived to be relatively weak (Panel D). The mean response is above two for all answers, yet the median in some cases equals three. In this situation, however, even a neutral response might be indicative of an unflattering perception.

The extent to which distributive justice represents a driver of tax compliance (LackEqty) is summed up by two questions (Panel E). The answer for both of them averages a number very close to four, while both medians equal four. Respondents agree that people evade taxation because they earn too little for how much they work, and have to pay too much tax for what they earn. In other words, non-compliance is perceived as a consequence of lack of distributive equity.

Respondents’ perceptions, with respect to accounting and other business practices aimed at evading taxation (BUSINESS), are captured by six questions (Panel F). It appears that cooking the books is not condoned, but the sentiment is not strong, albeit consistent. The mean response for all six questions is slightly larger than two, yet all medians equal two.

The extent to which tax compliance is driven by the fear of administrative or criminal penalties (FEAR_R) is summed up by four different questions (Panel G). The mean response is slightly lower than three. Fear does not appear to be an important driver of tax compliance. Fear of denunciation, in particular, appears of little concern to a majority of respondents. This is a very interesting result indeed. It suggests that the respondents either are not sensitive to extrinsic motivation, such as external penalties or rewards; or, that the threat of penalties is not really a concern, because the state is not capable of enforcing its own laws.

The level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the informal economy (TOLR) is captured by seven different questions (Panel H). The respondents seem to generally disapprove of tax evasion and informal practices albeit the sentiment is far from strong. In almost all cases, the mean response is higher than two, yet the median response is mostly two.

The findings shown in Panel A though H of

Supplementary Materials are summarized in

Table 1 according to each factor mentioned earlier. The first three variables show the median result obtained from a five-point Likert scale questionnaire. The remaining six variables show the median response of a five-point Likert scale questionnaire in the case of latent constructs obtained using factor analysis.

The essence of the findings so far can be further summarized in one paragraph: The respondents agree that compliance is a civic duty, perceive tax evasion as moderate, perceive extant tax evasion as the result of a lack of distributive justice, perceive the state as relatively weak, somewhat reject business practices aimed at evading taxation, and are relatively intolerant to noncompliance and the formal economy.

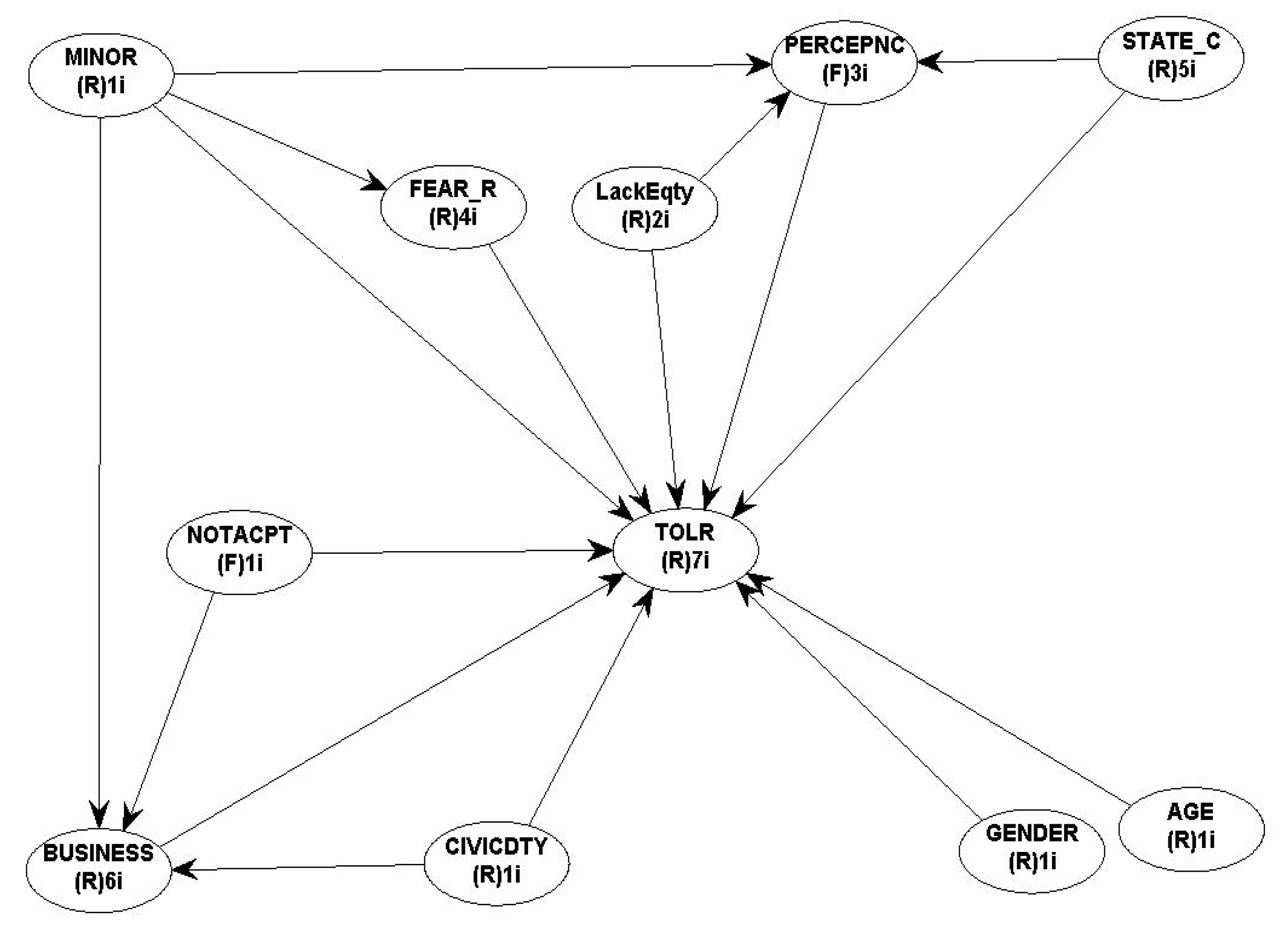

Next, we propose a Partial Least Square path modeling methodology, in which the outcome variable is represented by the individual level of tolerance to tax compliance and the informal economy (TOLR). We use five main predictors (State_C, MINOR, LackEqty, CIVICDTY, NOTACPT), and three mediators (PERCEPNC, FEAR_R, BUSINESS).

Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of the hypothesized model.

Our approach represents a very loose and truncated adaptation of the theory proposed by Ajzen (

Ajzen 1991;

Madden et al. 1992). This is due, in part, to the fact that we could not measure accurately the intention to comply, nor were we able to observe the actual behavior; and because there is mixed support in the literature for the theory of planned behavior in the case of tax evasion (

Bobek and Hatfield 2003;

Buchan 2005;

Trivedi et al. 2005).

We hypothesize that the perception of poor state capacity (STATE_C), the extent to which tax evasion is viewed as a minor infraction (MINOR), and the perception of lack of distributive equity (LackEqty) would increase the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and informal practices (TOLR). We also hypothesize that the beliefs that compliance is a civic duty (CIVICDTY) and tax evasion is not socially acceptable (NOTACPT) would decrease the level of tolerance towards noncompliance and informal practices (TOLR).

Two mediating variables (PERCEPNC and BUSINESS) are expected to be directly related to TOLR, for the reasons explained earlier. The latent construct FEAR_R, which represents a proxy for the severity of tax enforcement, is expected to have an inverse relationship to TOLR.

We hypothesize that the perception of tax evasion (PERCEPNC) would be directly related to STATE_C, MINOR, and LackEqty. MINOR is expected to be inversely related to FEAR_R, because if tax evasion is perceived to be a minor infraction, the fear of penalties would obviously be lower. The latent constructs CIVICDTY and NOTACPT are expected to be inversely related to BUSINESS. Finally, we expect older individuals and women to have a lower tolerance to tax evasion (TOLR).

5. Results

The PLS-PM model used here is estimating the impact of a system of predictors on the level of tolerance to non-compliance and the informal economy (

Götz et al. 2010). The method works by maximizing the explained variance of the dependent latent variable, that is, tolerance to non-compliance and the informal economy (TOLSR) via an iterative algorithm, based on ordinary least squares (OLS). Our PLS-PM model has been used in a way that is consistent with mainstream PLS methodology employed in the extant literature and has two parts: an outer/measurement model, and an inner model.

The outer model estimates the relationships among the latent and the corresponding manifest variables; the inner model, which represents the regression proper, estimates the relationships among predictors and outcome, including control and mediating variables. We use WarpPLS 6.0 (developed by Scriptwarp Systems), because this software is among a handful of packages able to handle both linear and non-linear relationships (

Kock 2016). The model has also been re-run in R (using PLSPM) and the results have been cross-checked against the results obtained with WarpPLS.

Table 2 reports the results of three metrics of reliability and internal consistency in the measurement stage (outer model): Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted.

All but one of Cronbach’s Alpha values are above 0.8, suggesting a very good reliability and internal consistency (

Fornell and Larcker 1981). With the exception of two constructs, composite reliability is also above 0.7, reinforcing the conclusion of reliability and internal consistency (

Nunnally and Ira 1994). With one exception, average variance extracted is above 0.5, showing that a good portion of the variance in the items measured in our questionnaire have been captured by the corresponding latent constructs (

Henseler et al. 2009;

Hair et al. 2012). Results below the critical values suggested in the literature might hint at the variance being the result of measurement errors.

Table 3 shows the combined loadings and cross-loadings of all indicator items, associated with their corresponding latent constructs. The values taken by factor loadings range from 0.656 to 0.884. These values are less than 0.7 in only two instances, showing an overall good correlation between the indicator items and the latent variables. All values are highly significant (

p < 0.001).

Table 4 shows the results pertaining to the discriminant validity of the measurement scales. The square roots of the AVEs are found on the main diagonal. These values are greater in all cases than the off-diagonal elements, suggesting that there is no overlapping in the constructs captured by the individual items. Moreover, we retain all latent variables in the model, because all of the off-diagonal correlations are lower than the critical threshold value of 0.8 (

Götz et al. 2010;

Henseler et al. 2009;

Esposito Vinzi et al. 2010).

The inner (structural) model: The structural model was estimated using Warp 3 procedure with bootstrapping. The algorithm converged after eight iterations. All VIF values are equal to or lower than 1.252, well below the critical threshold of 3.3, well within the acceptable range. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is 0.07, which is below the maximum acceptable threshold value of 0.08, suggesting a good fit (

Hu and Bentler 1999). No Simpson’s Paradox or bivariate causality directions were detected.

We are well aware that some potential limitations of our research might be the apparently small number of observations and a self-selection bias in our sample. After checking for common method bias we do not find any factor explaining more that 50% of the variance in our data. No VIF values indicative of such problems are higher than 1.5.

Moreover, as already mentioned, the methodology used is non-parametric, making inferences based on bootstrapping, an approach that compensates for a possible selection bias. Our inferences might have been problematic had we used a standard statistical analysis. The robustness of PLS-PM analysis is well documented in the literature: one can draw valid results from relatively small samples (

Willaby et al. 2015).

Table 5 reports the path coefficients and their significance levels, the R2 and adjusted R2 values for the endogenous constructs, and the effect sizes (similar to Cohen’s f2) of the outcome variable (TOLR). The overall model has a very good explanatory power, with an R2 of fifty percent and an adjusted R2 of forty eight percent. With a value of 0.39, the Tenenhaus goodness of fit coefficient qualifies as large.

The predictors of all three mediators are statistically significant. LackEqty, STATE_C, and MINOR are statistically significant predictors of PERCEPNC, explaining ten percent of its variance. Even better, MINOR, NOTACPT, and CIVICDTY are statistically significant predictors of BUSINESS, explaining thirteen percent of its variance. In fact, MINOR is a statistically significant predictor of three mediators: PERCEPNC, BUSINESS, and FEAR_R. However, the third mediator, FEAR_R, is the least explained, with an R2 of only three percent.

All three mediators are statistically significant predictors of the outcome variable, TOLR. The situation is more complex when it comes to the main predictors, because when evaluating total effects, one has to account separately for both direct and indirect effects.

Both LackEqty and STATE_C show total effects that are statistically insignificant. The lack of statistical significance is somewhat contrary to our expectations. NOTACPT shows a negative and statistically significant total effect (−0.251, p < 0.001). This effect can be deconstructed into a negative and statistically significant indirect effect (−0.082, p = 0.032), and a negative and statistically significant direct effect (−0.169, p = 0.003), suggesting that BUSINESS indeed acts as a partially mediating mechanism in the relationship between NOTACPT and TOLR.

CIVICDTY shows a negative and statistically significant total effect (−0.166, p = 0.004). However, after controlling for the BUSINESS mediator, the direct effect remains statistically insignificant (−0.085, p = 0.088), and a negative and statistically significant indirect effect (−0.081, p = 0.034 turns BUSINESS into a total mediator.

MINOR shows a positive and statistically significant total effect. The cumulative indirect effect of all three mediators associated with MINOR (that is, PERCEPNC, BUSINESS, and FEAR_R) is positive, yet not statistically significant (0.026, p = 0.338).

The impact of AGE on TOLR is negative and significant (−0.178, p = 0.002). According to our results, however, there is no significant relationship between GENDER and TOLR (−0.027, p = 0.333).

Table 6 reports effect sizes. The tolerance towards accounting and other business practices aimed at avoiding and evading taxation (BUSINESS) has the highest contribution to the outcome variable (effect size equal to 0.273), suggesting that intervention on the former results in a medium effect on the latter (

Cohen 1988).

The perception of lack of equity (LackEqty) appears to have a small effect on the perception of tax non-compliance (PERCEPNC, effect size equal to 0.069). The perception that tax evasion represents a minor infraction (MINOR) also has a small effect on the tolerance towards accounting and other business practices aimed at avoiding and evading taxation (BUSINESS), on the extent to which tax compliance is driven by fear of administrative or criminal penalties (FEAR_R), and on the outcome variable (effect sizes equal to 0.041, 0.03, and 0.039 respectively).

The perception that tax evasion is not socially acceptable (NOTACPT) has a small effect on the tolerance towards accounting and other business practices aimed at avoiding and evading taxation (BUSINESS) and the outcome variable (effect sizes of 0.043 and 0.053). Finally, the perception that tax compliance is a civic duty (CIVICDTY) has a small effect on the tolerance towards accounting and other business practices aimed at avoiding and evading taxation (BUSINESS, effect size equal to 0.048). All other effects are below the minimum threshold of 0.02, hence too weak to be practically relevant, in spite of statistically significant relationships with the outcome variable.

6. Further Interpretation and Discussion

The perception of state capacity (STATE_C) does not appear to influence the level of tolerance to non-compliance and the informal economy (TOLR), either directly, or through the mediation of the perception of tax evasion (PERCEPNC). The only notable impact is on the perception of non-compliance (PERCEPNC).

The weaker the state is perceived to be, the stronger the perception of tax evasion. This result is consistent with expectations. However, effect sizes are far too small to warrant any intervention.

The perception of tax evasion and/or non-compliance (PERCEPNC) appears to be inversely related to the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and/or non-compliance (TOLR). This result is not consistent with initial expectations. PERCEPNC only appears to act as a mediating factor for other latent variables, but the indirect effects are either statistically insignificant (in the case of STATE_C), or only marginally significant (in the case of LackEqty).

After controlling for the mediator, there is no statistically significant direct effect in the relationship between the perceived lack of distributive equity (LackEqty), and the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the informal economy (TOLR). This result is not consistent with expectations. However, the indirect effect is marginally significant: the more one perceives that noncompliance is driven by lack of distributive equity, the stronger the perception of tax evasion, which in turns decreases the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the informal economy. Because the direct relationship between LackEqty and TOLR is not statistically significant, PERCEPNC acts as a total mediator in the aforementioned relationship.

The more one disagrees that tax evasion is a minor infraction (MINOR), the lower the tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR). This result is consistent with expectations. Moreover, there are two mediated effects: The more one agrees that tax evasion is a minor infraction, the less likely one is to perceive fear as a driver of compliance (FEAR_R); the explanatory power is small, but the estimated coefficient is significant, which in turn, is directly related to the level of tolerance towards tax evasion. It is not entirely clear if the indirect effect is significant because there are three distinct, yet simultaneous, indirect effects that are lumped together. The more one agrees tax evasion is a minor infraction (MINOR), the more one will endorse cooking the books (BUSINESS), which in turn is directly related to the tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR).

The more one perceives tax evasion as unacceptable (NOTACPT), the lower the level of tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR). This result is consistent with expectations. There is also a mediated effect: The more one perceives tax evasion as unacceptable, the lower the level of endorsement of creative accounting (BUSINESS), which in turn is directly related to the level of tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR). In other words, because both direct and indirect effects are significant, BUSINESS is a partial mediator.

There is a total effect, showing that the more one perceives compliance as a civic duty (CIVICDTY), the lower the level of tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR). When controlling for BUSINESS as a mediator, the indirect effect appears statistically significant: the more one perceives compliance as a civic duty, the lower the level of endorsement of creative accounting (BUSINESS), which in turn is directly related to the level of tolerance towards tax evasion (TOLR). Moreover, because the direct effect between CIVICDTY and TOLR is not statistically significant, BUSINESS appears as a total mediator. This result is partially consistent with expectations.

Finally, as already mentioned several times earlier, the less one endorses creative accounting, the less tolerant one is towards tax evasion and the informal economy. This result is fully consistent with our prior expectations.

7. Policy Implications

This research allows us to consider several policy implications and intervention possibilities. These are mainly based on the direction of the relationships among variables, statistical significance and effect size. As long as the effect size is larger than 0.02, there exists a real possibility for consequential intervention.

A first candidate is the perception of noncompliance. According to our findings, the more acute this perception, the lower the level of tolerance towards tax evasion and the informal economy. Although the effect size is small (0.057 > 0.02), it is worth pursuing a course of action that would sensitize the public to the economic and social consequences of tax evasion. It goes without saying that the process of sensitization has to be carried out tactfully and tastefully, lest running the risk of transforming it into a caricature with adverse effects, given the level of skepticism, suspicion, and even cynicism characteristic of post-communist Romania.

We have established that compliance driven by fear of penalties has an adverse impact on the level of tolerance towards tax evasion. The relationship is statistically significant, yet the effect size is minuscule, not warranting any intervention. If anything, this finding reinforces the conclusion that the participants in the questionnaire appear to reject an extrinsic motivation for compliance.

Tolerance to business accounting practices aimed at avoiding and evading taxation represents a total mediator for the belief that tax compliance is a civic duty in its relationship with the level of tolerance to tax evasion; a partial mediator for the belief that tax evasion is not socially acceptable in its relationship with the level of tolerance to tax evasion; and perhaps a mediator for the belief that tax evasion is a minor offense.

There is a significant relationship between the level of tolerance to business accounting practices aimed at evading taxation and the outcome variable. The effect size of the relationship is moderate (0.273), therefore, an effective intervention should act on reinforcing the belief that tax compliance is a civic duty and that tax evasion is not socially acceptable. Moreover, one should also concentrate on dispelling the perception that tax evasion is a minor offense. All three variables have small effect sizes, but within the suitable range for intervention.

Can one generalize the results presented here to other former communist, Eastern European countries? Moreover, if so, are the conclusions and recommendations discussed above applicable in those countries? This is a legitimate question, yet it is not easy to answer with a simple yes or no. Several of our findings are corroborated by similar research (

Williams et al. 2015;

Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Gërxhani 2016). Most work has been done on the relationship between the quality of institutions and tax morale. There is sufficient evidence to conclude that the perception of state capacity is linked to the level of civic engagement and tolerance towards the shadow economy (

Torgler 2011;

Hug and Spörri 2011), but this finding can be easily generalized to all social or liberal democracies; it is not specific to Eastern Europe alone. However, unlike the studies cited here, we find the direct relationship between the perception of state capacity and tolerance towards the shadow economy to be weak and insignificant. We explain this by citing the influence of mediating factors specific to the Romanian context.

As indicated in the introduction, our paper takes a distinctive approach. Because we formulate very specific hypotheses and employ a very particular methodology, our results are not directly comparable to those of other studies. We can only speculate that, given the historical and cultural similarities between Romania and the other Eastern European countries, some of our findings are probably indicative of what might be going on in Bulgaria, Poland, Slovakia, Russia and the rest (

Wyslocka and Tatsiana 2016;

Tsindeliani et al. 2019). At the same time, the level of tax evasion and the relative size of the informal economy is not the same in all countries. Moreover, (

Torgler 2003) finds that tax morale in Eastern European countries is higher than that present in the countries of the former Soviet Union. These considerations should have a sobering effect on one’s inclination to make generalizations: perhaps there are other differences, which are more nuanced and subtle, but not yet documented.

8. Concluding Remarks

We set out to determine the true perception of state capacity, the general level of tolerance towards noncompliance and the shadow economy, and the factors that influence these attitudes. This is a topic of great importance for a country like Romania who seeks to modernize the public sector, boost the economy, and pursue a harmonious integration in the European Union.

After evaluating the questionnaire, it is clear that our respondents perceive the state to be relatively weak and tax evasion moderate. These results, however, do not seem to match the media hype. It can be argued that the media tends to exaggerate in a bid to capture an increasing audience with sensational revelations and shocking news. While there are no objective metrics for media histrionics and distortions, one can make the case that the audience simply displays a healthy dose of skepticism. Or, it could simply be that the audience is tuning out, having become apathetic, and perhaps even callous.

It is encouraging, however, to find that our respondents are somewhat intolerant of tax evasion and the informal economy. The level of intolerance appears to be higher than that suggested in the media, yet not as high as one would hope. True, the perception of a weak state makes the respondents more tolerant towards tax evasion, but the effect is neither strong nor significant. It is the perception of tax evasion that pulls in the opposite direction. This is one of the most intriguing findings, for our initial expectation was just the opposite. We had reasoned that constant exposure to reports of tax evasion and dismal state capacity would desensitize the audience and somehow signal that “everyone is doing it,” making it appear commonplace and thus more acceptable. This is essentially an availability bias argument.

Instead, the finding could be interpreted through the lenses of a representativity bias. If the instances showcased in the media are blown out of proportions such that they lie outside the range of everyday experience, it is easier for individuals to dissociate themselves from such morally outrageous situations. This moral disentanglement is nevertheless subtle and nuanced. It is probably not the case that our respondents believe they are righteous and blameless; but perhaps they fathom that they are not as bad as the offenders portrayed in mass media. This attitude enables a credible absolution and probably mitigates any extant cognitive dissonance. In the words of (

Klein and Epley 2016), “Believing one “less evil than thou” seems more reliable and safer than believing one is “holier than thou.”” That is, self-enhancement takes place in the process (

Tappin and McKay 2017).

Another interesting result shows that compliance driven by fear of penalties is in fact increasing the level of tolerance to tax evasion. Although the effect size is too small to matter from a practical perspective, a direct implication of this finding suggests that, in order to reduce the tolerance to tax evasion, one should reduce the threat of penalties instead of increasing them. Our respondents seem to reject extrinsic motivation and instead embrace intrinsic motivation. This conclusion is consistent with the literature on tax evasion, contending that the level of compliance is indeed much higher than warranted by the severity of administrative penalties and the monetary costs associated with noncompliance (

Feld and Frey 2007). Last, but not least, the perception of lack of distributive equity (through the mediation of perception of noncompliance) and civic mindedness pull in the same direction. There is consistency in our results: tax evasion is rejected and not considered a minor issue, which is indeed consistent with the concept of civic duty.

Effect sizes are moderate and small, and this allows policy intervention, especially when it comes to sensitizing the public to the social and economic costs of tax evasion. Another possible direction for policy intervention is to reinforce the notion that tax compliance is a civic duty and that the alternative is not socially acceptable. All our findings suggest an architecture of choice that would reduce, when possible, the emphasis on coercion and punishment and promote civic engagement. However, this is easier said than done.

We are reluctant to make sweeping generalizations and extend the applicability of our specific conclusions to all the countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Nevertheless, it has become obvious that, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, one of the most formidable challenges of post-communist transition in Eastern Europe, especially in Romania, has been by far the promotion of civic engagement, and the building of social trust.