Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders about Environmental Issues at a Nature-Based Tourism Destination: The Case of Yakushima Island, Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

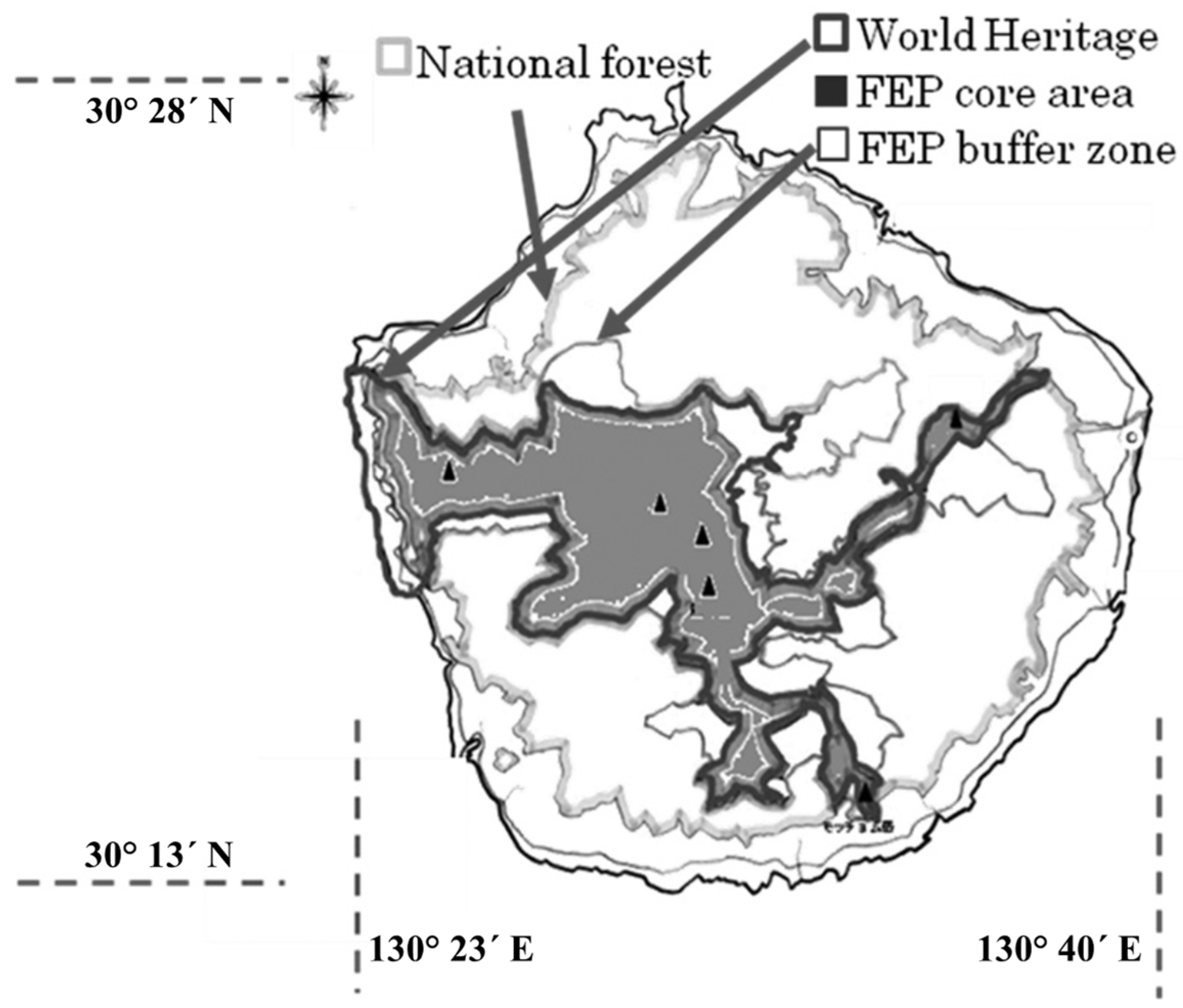

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Review of Environmental Discussions on Yakushima over the Past Two Decades

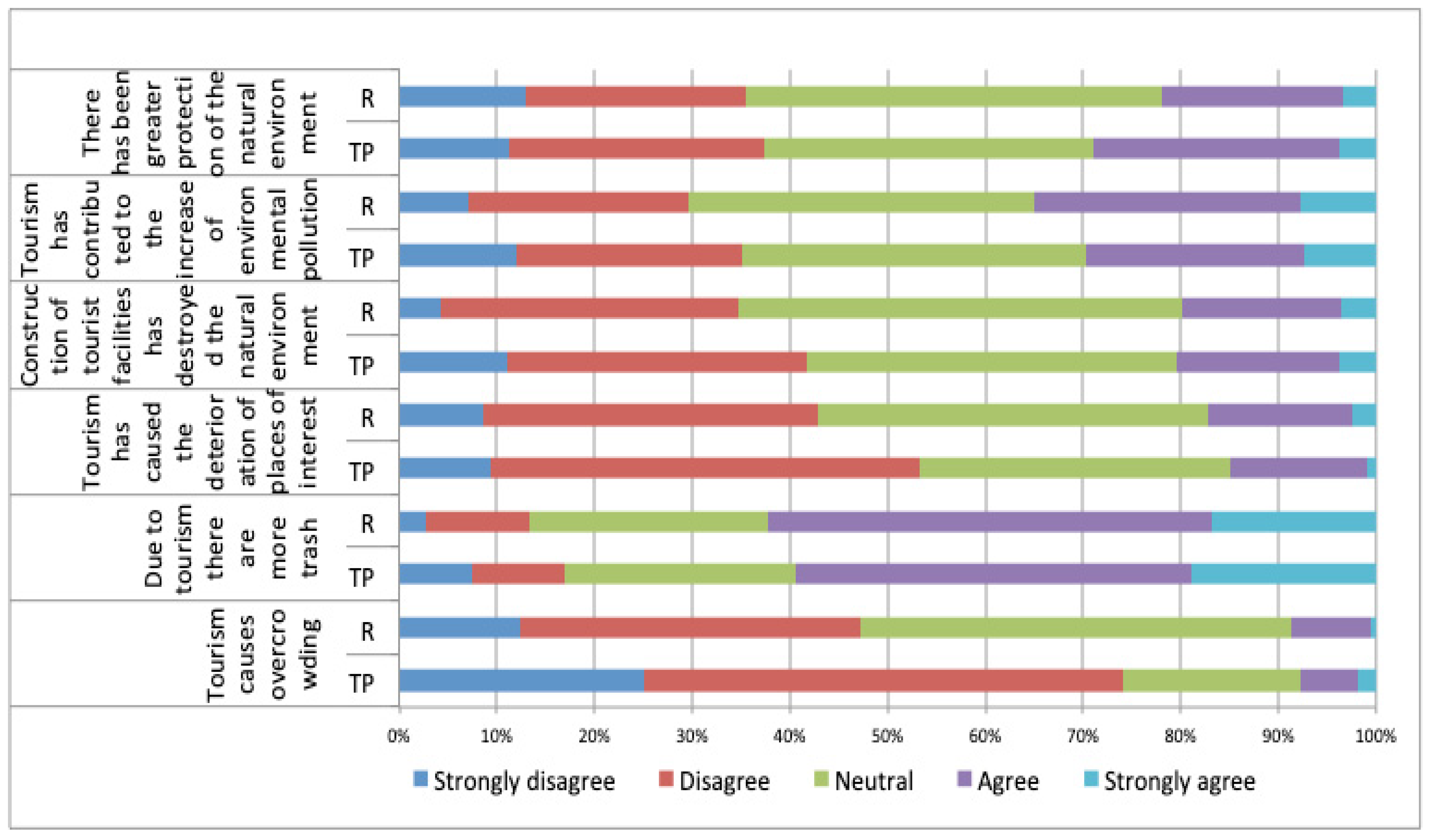

3.2. Impacts of Tourism on the Environment as Perceived by Residents and Tourism Practitioners

3.3. Perceptions of Administration about Environmental Issues Connected to Tourism

3.4. Perceptions of Environmental Issues Connected to Deer Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzi, C.; McNeely, J. Nature-Based Tourism. In Global Risk Governance: Concept and Practice Using the IRGC Framework; Renn, O., Walker, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, B.; Lee, J. Visitor experience in Kafue National Park, Zambia. J. Ecotour. 2017, 16, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, H.; Yun, S.-J. Revisiting the Concept of Common Pool Resources: Beyond Ostrom. Dev. Soc. 2017, 46, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C.B.; Norgaard, R.B.; Policansky, D. Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science 1999, 284, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.S.; Huang, Y.Y. Common-Pool Resources, ecotourism and sustainable development. Taipei Econ. Inq. 2017, 53, 87–128. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Duim, R.; Caalders, J. Biodiversity and tourism: Impacts and interventions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, L. Managing biodiversity for a competitive ecotourism industry in tropical developing countries: New opportunities in biological fields. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janér, A.; Bezerra, N.P.; Ozorio, R.Z. Mamiraua: Community-Based Ecotourism in a Sustainable Development Reserve in the Amazon Basin. In Sustainable Hospitality and Tourism as Motors for Development; Sloan, P., Simons-Kaufmann, C., Legrand, W., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, E. Ecotourism can harm the environment. In What is the Impact of Tourism? Espejo, R., Ed.; Greenhaven Press: Farmington Hills, Michigan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- English, B.J. Is Ecotourism Just Another Story of Paradise Lost? Tama Univ. Dep. Bull. 2017, 9, 1–12. Available online: http://id.nii.ac.jp/1361/00000881/ (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Nackoney, J.; Molinario, G.; Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Furuichi, T. Impacts of civil conflict on primary forest habitat in northern Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1990–2010. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 170, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, D.; Anthony, B.P. Application of modified threat reduction assessments in Lebanon. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Sustainable Wildlife Management and Human−Wildlife Conflict; No 4 CPW Factsheet; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R.M.A.; Beardall, V. The impact of deer on woodlands: The effects of browsing and seed dispersal on vegetation structure and composition. Forestry 2001, 74, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeck, C.W.; Schultz, A.K. Community-level impacts of white-tailed deer on understorey plants in North American forests: A meta-analysis. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plv119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnani, K.M.; Klips, R.A.; Curtis, P.S. Regeneration of woodland vegetation after deer browsing in Sharon Woods Metro Park, Franklin County, Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 2006, 106, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H.; Takatsuki, S. Effects of deer grazing on vegetation and ground-dwelling insects in a Larch Forest in Okutama, Western Tokyo. Int. J. For. Res. 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, D.; Pellow, B.J. Effects of Javan rusa deer (Cervus timorensis) on native plant species in the Jibbon-Bundeena Area, Royal National Park, New South Wales. Linn. Soc. N. S. Wales 2005, 126, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y.; Xu, S.S. Stifled stakeholders and subdued participation: Interpreting local responses toward Shimentai Nature Reserve in South China. Environ. Manag. 2002, 30, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Rabinowitz, A.; Khaing, S.T. Status review of the protected-area system in Myanmar, with recommendations for conservation planning. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, Y.; Fu, B. Local people’s perceptions as decision support for protected area management in Wolong Biosphere Reserve, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaborations and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Bosley, H.E.; Dronberger, M.G. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, Y. The perceptual differences among stakeholders in the tourism supply of Xi’an City, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K. Community groups’ perceptions of and preferences for tourism development: Evidence from Crete. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, S.V. Attitudes and perceptions toward tourism and rural regional development. J. Travel Res. 1994, 32, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.L.; Beeton, R.J.S. Sustainable tourism or maintainable tourism: Managing resources for more than average outcomes. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Huang, S.S. Effect of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Fyall, A. Destination service quality, affective image and revisit intention: The moderating role of past experience. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livina, A.; Reddy, M. Nature Park as a resource for Nature-Based Tourism. Environ. Technol. Resour. 2017, I, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.E. Nature-based tourism in a Japanese national park: A case study of Kamikochi. Bull. Tokyo Univ. For. 2009, 121, 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. A life cycle analysis of nature-based tourism policy in Japan. Contemp. Jpn. 2012, 24, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Havens, T. Parkscapes: Green Spaces in Modern Japan; University of Hawaii Pres: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, G. Yakushima: Balancing long-term environmental sustainability and economic opportunity. Kagoshima Immacul. Heart Coll. Res. Bull. 2012, 42, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki, S.; Hikita, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Nagata, N. The influence of World Natural Heritage Registration on the management system of regional resources. For. Econ. 2006, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, H. Local residents perception on forest recreation from the example of Yakushima. J. For. Econ. 2007, 43, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, H.; Yumoto, T.; Okano, T.; Tetsuka, T.; Fujimaki, A.; Shioya, K. An extension plan of Yakushima Biosphere Reserve as a case study of consensus building of islanders. J. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 38, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okano, T.; Matsuda, H. Bio-cultural diversity of Yakushima Island: Mountains, beaches, and sea. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2013, 2, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y. The community residents’ perceptions toward forest recreation: Yakushima Island as a case study. J. For. Econ. 1997, 43, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki, S.; Shoji, Y.; Tsuge, T.; Tsuchiya, T.; Nagata, N. The possibility of community participation in world heritage management: Exploring residents’ perceptions of Yakushima Island in Kagoshima. Chikyū Kankyō 2008, 13, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Uebayashi, Y. The current situation and challenges of tourism at Yakushima Island: Based on the resident’s perception. Ryūkoku Daigaku Daigakuin Keizai Kenkyū 2011, 11, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, Y. The current situation of forest recreation in the government-owned land: The opinions of Yakusugi Land users. J. For. Econ. 1995, 127, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, S.; Niki, K. The environmental conservation consciousness of visitors to Yakushima, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Chiiki Kankyō Kenkyū 2012, 4, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Adewumi, I.B.; Funck, C. Ecotourism in Yakushima: Perception of the People Involved in Tourism Business. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 71, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, H. Yakushima-Japan: Sustainable Forest Management. In Sustainable Plantation Forestry: Problems, Challenges and Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, A.; Yoshihiro, S.; Takahata, Y.; Manda, M.; Furuichi, T.; Kurihara, Y.; Hayaishi, S.; Hanya, G. Changes of abundance of Japanese macaques in Yakushima over the past 20 years. Primate Res. 2017, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K. A new economic use of forest resources and the persons in charge: From the example of ecotour guides in Yakushima. J. For. Econ. 2001, 47, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, Y. Ecotourism in Yaku-Island, Kagoshima Prefecture. Kagoshima Daigaku Kyoikugakubu Kenkyukiyo 2004, 55, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki, S. Economic analysis of the ecotourism industries in Yakushima Island. Bull. Natl. Mus. Jpn. Hist. 2015, 93, 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kanetaka, F.; Funck, C. The development of the tourism industry in Yakushima and its spatial characteristics. Stud. Environ. Sci. 2011, 6, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kavallinis, I.; Pizam, A. The environmental impact of tourism: Whose responsibility is it anyway? The case study of Mykonos. J. Travel Res. 1994, 33, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokulil, M.T. Environmental Impacts of Tourism on Lakes. In Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control; Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sunlu, U. Environmental impacts of tourism. In Local Resources and Global Trades: Environments and Agriculture in the Mediterranean Region; Camarda, D., Grassini, L., Eds.; CIHEAM: Bari, Italy, 2003; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Mousavi, M.S.S. The Role of Tourism on the Environment and Its Governing Law. Electron. J. Biol. 2017, 13, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W. A structural equation model of residents attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Valentine, K.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvan, Y.; Akan, P. Residents’ attitudes toward general and forest-related impacts of tourism: The case of Belek, Antalya. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bahadur, R. Environmental Impacts of Tourism: A Case Study of Jammu and Kashmir. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 6, 860–875. [Google Scholar]

- Grössling, S.; Hall, M.; Scott, D. Tourism and Water; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lohchab, R.K. Socio-economic and environmental impacts of tourism at Bhimtal and its management. Ann. Agri-Bio Res. 2010, 15, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, M.C.; Ramayah, T.; Hui, H.L.H. Rural Communities Perceptions and Attitudes towards Environment Tourism Development. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Díaz-Armas, R.; Gutierrez-Taño, D. Residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts on island destinations: A Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, P.; Sharpley, R. Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community wellbeing: The case of Mauritius. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 5, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pavel-Nedea, A.; Dona, I. Assessment of residents’ attitudes towards tourism and his impact on communities in the Danube Delta. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2017, 17, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M. Ecotourism: Who Owns Paradise? 2nd ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, J. Critical Issues in Eco-Tourism: Understanding a Complex Tourist Phenomenon; Oxford Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, M.; Pour, S.A. Effects of economic, social and environmental factors of tourism on improvement of perceptions of local population about tourism: Kashan touristic city, Iran. Ayer 2014, 4, 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Li, S.M. The impact of tourism development on the environment in china. Acta Sci. Malays. 2018, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumoto, T.; Matsuda, Y. Deer Eat World Heritage: Ecology of Deer and Forest; Bunichi Sōgō Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Year | No. of Articles | Articles Chosen | Issues | Management Policies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 54 | 2 | Too many hikers to Jomonsugi cause trampling damage | |

| Too many tourists disturb sea turtles | ||||

| 2010 | 65 | 4 | Increase in tourists causing a burden for the environment | Support for introduction of Electronic Vehicles |

| Transport of toilet sewage from mountain area | Promote disposable toilets to hikers | |||

| Increase in tourists to Jomonsugi | Introduction of traffic restrictions | |||

| Diversification of tourist activities | Start of village tours on local culture | |||

| Congestion at Jomonsugi | Publish calendar with congestion predictions | |||

| 2011 | 45 | 10 *1 | Congestion at Jomonsugi | Discussion on limitation of visitors to Jomonsugi |

| Proposal dismissed in town council for economic reasons | ||||

| Issue in mayor election | ||||

| Cost of toilet disposal from mountain area | Introduction of bio-toilet | |||

| Congestion at Jomonsugi leads to trampling damage | Suggestion: make guide compulsory | |||

| 2012 | 48 | 3 | Restriction on smoking along Jomonsugi trail | |

| Issues of congestion, deer damage | New monitor plan for Yakushima: first change since WH registration | |||

| Success: more than 100 electric cars | ||||

| 2013 | 79 *2 | 2 | 20 years since designation: still problems of congestion and toilets on Jomonsugi trail | |

| Discussion on island tax to cover costs for toilet disposal etc. | ||||

| 2014 | 55 | 1 | (Reflection: effects of WH registration) | |

| 2015 | 73 *3 | 4 | Discussion on donation system for hikers | |

| Widening of access road to mountain area threatens rare flower species | ||||

| Report on environmental situation in Scientific Committee: no. of hunted deer, toilets | ||||

| Idea to use former mountain rail for tourists | ||||

| 2016 | 56 | 10 *4 | New guide registration and qualification system introduced | |

| Number of hikers decreasing | Suggestion: new hiking style should be developed | |||

| Introduction of mountain donation decided | ||||

| (Series on 50 years discovery of Jomonsugi: history of preservation, new ideas for better hiking environment) | ||||

| Problems at mountain huts: garbage etc. | Suggestion: install managers during high season | |||

| 2017 | 55 | 7 | Concentration of hikers, toilet sewage disposal, quality of mountain huts | Discussion on management methods for five years |

| Start of mountain donation system | ||||

| Water quality | ||||

| Widening of access road to mountain area threatens rare flower species | Investigation conducted | |||

| Electric vehicle car rental started | ||||

| Increase in international visitors | Necessary: information, safety measures | |||

| Number of hikers and accidents | ||||

| 2018 | 47 | 5 | NPO that supported conservation of sea turtles gives up activities | Discussion on rules for sea turtle observation tours |

| NPO finds successor for activities | ||||

| (Residents meeting) | Suggestion on use of cedars, deer |

| Environmental Impacts of Tourism | R | TP | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| There has been greater protection of the natural environment due to tourism | 2.581 | 1.1976 | 2.739 | 1.1577 | −1.116 | 0.265 |

| Tourism has contributed to the increase of environmental pollution | 2.825 | 1.2933 | 2.820 | 1.1924 | 0.035 | 0.972 |

| The construction of hotels and other tourist facilities has destroyed the natural environment of Yakushima | 2.582 | 1.1706 | 2.640 | 1.0770 | −0.426 | 0.671 |

| Tourism has caused the deterioration of places of historical and cultural interest | 2.362 | 1.2219 | 2.441 | .9880 | −0.610 | 0.542 |

| Due to tourism there are more trash in the community | 3.557 | 1.2648 | 3.409 | 1.2943 | 0.963 | 0.336 |

| Tourism causes overcrowding in the community | 2.185 | 1.1397 | 1.955 | 1.0344 | 1.780 | 0.076 |

| Environmental Issues Connected to Tourism | Causes of the Issues | Interviewed Organization Stating the Issues | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure on mountain trails to Jomonsugi resulting in damage of the trails | Congestion along Jomonsugi trail | Yakushima Environmental Culture Village Center | Damage to the forest and equipment |

| Yakushima World Heritage Conservation Center | Damages to the trails | ||

| Yakushima Tourism Association | Constant repair of trails is required | ||

| Yakushima Forest Conservation Center | Damages to the trails | ||

| Vegetation trampling | People walk on the vegetation | Yakushima World Heritage Conservation Center | Threat of some rare species becoming endangered |

| Damages to soil structure | Use of walking sticks/hiking poles | Yakushima World Heritage Conservation Center | |

| Human waste (sewage) management | Toilets in the mountains | Yakushima Environmental Culture Village Center | Need for more toilets to be able to cope with the increase in tourists |

| Yakushima World Heritage Conservation Center | |||

| Treatment of sewage to prevent contamination of rivers | Yakushima Tourism Association | Carried down the mountains for proper disposal | |

| Strenuous and expensive | |||

| Wastes flow into nearby rivers during the tourism season | Town councillor | ||

| Increase of garbage in the mountains | Increase in number of tourists | Yakushima World Heritage Conservation Center | |

| Problem of maintaining the natural environment and increase in tourist | Increase in tourists | Yakushima Environmental Culture Village Center | Efforts are being made to balance both tourism and environmental management |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adewumi, I.B.; Usui, R.; Funck, C. Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders about Environmental Issues at a Nature-Based Tourism Destination: The Case of Yakushima Island, Japan. Environments 2019, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6080093

Adewumi IB, Usui R, Funck C. Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders about Environmental Issues at a Nature-Based Tourism Destination: The Case of Yakushima Island, Japan. Environments. 2019; 6(8):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6080093

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdewumi, Ifeoluwa Bolanle, Rie Usui, and Carolin Funck. 2019. "Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders about Environmental Issues at a Nature-Based Tourism Destination: The Case of Yakushima Island, Japan" Environments 6, no. 8: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6080093

APA StyleAdewumi, I. B., Usui, R., & Funck, C. (2019). Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders about Environmental Issues at a Nature-Based Tourism Destination: The Case of Yakushima Island, Japan. Environments, 6(8), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6080093