The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values

Abstract

:1. Introduction

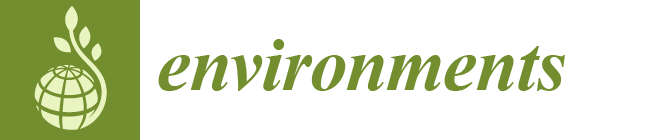

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Green IT Adoption

Theory of Consumption Value

Functional Value

Social Value

Epistemic Value

Emotional Value

Conditional Value

Reasons to Include Religious Values

Religious Value

“Who made all things good which He created (Quran, 32:7). And we are commanded to keep it that way: Do no mischief on the Earth, after it hath been set in order”.(Quran, 7:56)

“Then We appointed you viceroys in the Earth after them, that We might see how you behave”.(Quran 10:14)

“If a Muslim plants a tree or sows seeds, and then a bird, or a person or an animal eats from it, it is regarded as a charitable gift (sadaqah) for him”.(Sahih Bukhari, 513)

“He used to repair his shoes, sow his clothes and used to do all such household works done by an average person”.(Authenticated by Al-Albani)

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

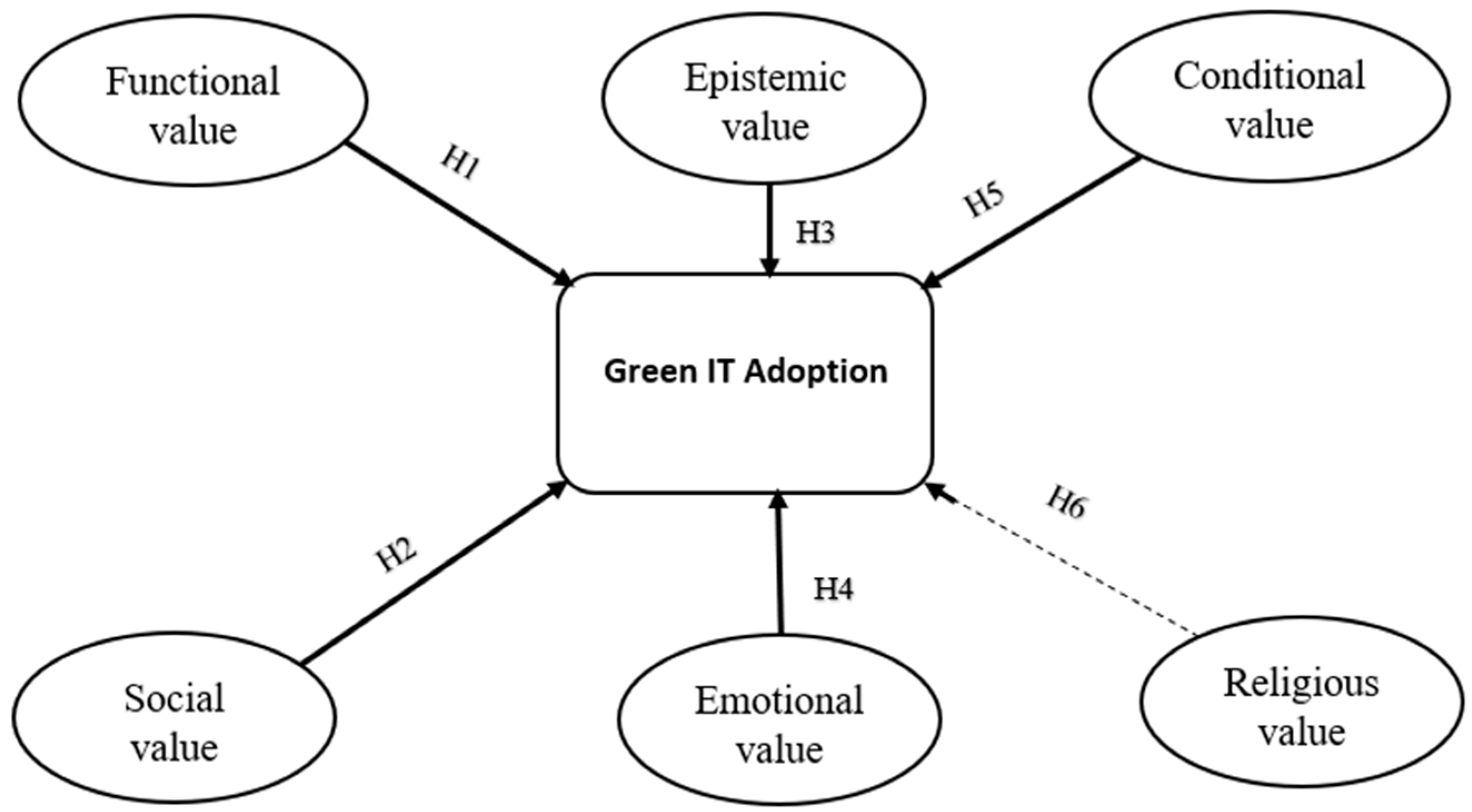

3.1. Measurement Model

3.2. Structured Model

4. Discussion

Limitation and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezdar, S. Green information technology adoption: Influencing factors and extension of theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haytko, D.; Matulich, E. Green advertising and environmentally responsible consumer behaviors: Linkages examined. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2008, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Do Paço, A.; Shiel, C.; Alves, H. A new model for testing green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A.; Rahman, S.U.; Salo, J. Antecedents of green behavioral intentions: A cross-country study of Turkey, Finland and Pakistan. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.M.; Ali, B.; Ahmad, M.S.; Thurasamy, R.; Amin, N. Factors Affecting Purchase Intention and Social Media Publicity of Green Products: The Mediating Role of Concern for Consequences. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patón-romero, J.D.; Baldassarre, M.T.; Rodríguez, M.; Piattini, M. Computer Standards & Interfaces Green IT Governance and Management based on ISO/IEC 15504. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2018, 60, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q.; Ji, S.; Wang, Y. Green IT practice disclosure: An examination of corporate sustainability reporting in IT sector. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 2017, 15, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Binti, A.; Ramayah, T.; Molla, A. Information & Management Senior managers’ perception on green information systems (IS) adoption and environmental performance: Results from a field survey. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Balde, C.P.; Forti, V.; Gray, V.; Kuehr, R.; Stegmann, P. The Global E-Waste Monitor 2017: Quantities, Flows and Resources; United Nations University: Bonn, Geneva; International Telecommunication Union: Bonn, Geneva; International Solid Waste Association: Bonn, Geneva, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi, S.; Razak, A.; Hussin, C.; Mohamed, H. Organizational research in the field of Green IT: A systematic literature review from 2007 to 2016. Telemat. Inf. 2017, 34, 1191–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/IEA, International Energy Agency. Global Energy & CO2 Status Report 2017; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sanita, F.; Udin, Z.M.; Hasnan, N. Green it/s adoption within gscm in indonesian construction industry: An elucidation and practice. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2017, 2, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, N.P. Information systems innovation for environmental sustainability. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedera, D.; Tushi, B.; Tan, F. Multi-disciplinary Green IT Archival Analysis: A Pathway for Future Studies Pathway for Future Studies. CAIS 2017, 41, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainin, S.; Naqshbandi, M.M.; Dezdar, S. Impact of adoption of Green IT practices on organizational performance. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 1929–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushi, B.T.; Sedera, D.; Recker, J. Green IT Segment Analysis: An Academic Literature Review. Am. Conf. Inf. Syst. 2014, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Ivković, A.F. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nam, C.; Dong, H.; Lee, Y.A. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention of green sportswear. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N. Green wine packaging: Targeting environmental consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2010, 22, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.B.; Jin, B. Predictors of purchase intention toward green apparel products. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. An Int. J. 2017, 21, 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, N.L.; Ariffin, S.K.; Nee, G.Y.; Wahid, N.A. A Study of Factors influencing Consumer’s Purchase Intention toward Green Vehicles: Evidence from Malaysia. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chang, C.Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, H.; Akbar, M.; Akhtar, W.; Zahid, H. Determinants of Consumer Intentions to Purchase Energy-Saving Household Products in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthiannopkao, S.; Wong, M.H. Handling e-waste in developed and developing countries: Initiatives, practices, and consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463–464, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Breivik, K.; Syed, J.H.; Malik, R.N.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Jones, K.C. Emerging issue of e-waste in Pakistan: A review of status, research needs and data gaps. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, M.; Syed, J.H.; Breivik, K.; Chaudhry, M.J.I.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Malik, R.N. E-Waste Driven Pollution in Pakistan: The First Evidence of Environmental and Human Exposure to Flame Retardants (FRs) in Karachi City. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13895–13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Haydar, S.; Kim, J.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, A. Resources, Conservation & Recycling E-waste flows, resource recovery and improvement of legal framework in Pakistan. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kessides, I.N. Chaos in power: Pakistan’ s electricity crisis. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M. Pakistan’s electricity generation has increased over time. So why do we still not have uninterrupted supply?—DAWN.COM. Dawn, 13 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FDGP. Pakistan Economic Survey 2017–2018; Faculty of General Dental Practice: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, R.; Luo, X. Integrative framework for assessing firms’ potential to undertake Green IT initiatives via virtualization—A theoretical perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, P.; Tate, M.; Toland, J. Small business in a small country: Attitudes to ‘Green’ IT. Carbon Footpr. Prod. 2013, 15, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Abareshi, A.; Cooper, V. Green IT beliefs and pro-environmental IT practices among IT professionals. Inf. Technol. People 2014, 27, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.; Chung, N. Examining the eco-technological knowledge of Smart Green IT adoption behavior: A self-determination perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 88, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C. Extending the TAM for Green IT: A Normative. Comput. Human Behav. 2018, 83, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Abareshi, A. Organizational green motivations for information technology: Empirical study. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2012, 52, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, T.; Noor, N.A.M. What affects Malaysian consumers’ intention to purchase hybrid car? Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Solaiman, M.; Halim, M.S.A.; Manaf, A.H.A.; Noor, N.A.M.; Noor, I.M.; Rana, S.S. Consumption Values and Green Purchase Behaviour an Empirical Study. Int. Bus. Manag. 2017, 11, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wier, M.; Doherty, K.O.; Laura, M.; Millock, K. The character of demand in mature organic food markets: Great Britain and Denmark compared. Food Policy 2008, 33, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A. A consumption value-gap analysis for sustainable consumption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7714–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, H. Effect of Consumption Values on Women’s Choice Behavior Toward Organic Foods: The Case of Organic Yogurt in Iran. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, H.; Rajabpour, S. Identifying effective factors on consumers’ choice behavior toward green products: The case of Tehran, the capital of Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harizan, S.H.M.; Rahman, W.A.W.A. Spirituality of Green Purchase Behavior: Does Religious Segmentation Matter? J. Res. Mark. 2017, 6, 473–484. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.N.; Kirmani, M.D. Role of religiosity in purchase of green products by Muslim students: Empirical evidences from India. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Mutum, D.S.; Ariswibowo, N. Impact of religious values and habit on an extended green purchase behaviour model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Chandrasekaran, U. Religiosity and Ecologically Conscious Consumption Behaviour. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2015, 5, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Chandrasekaran, U. Effect of religiosity on ecologically conscious consumption behaviour. Asian J. Islamic Mark. 2016, 7, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.H. The role of Islamic values on green purchase intention. J. Islam. Mark. 2014, 5, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiek, M. The effect of religiosity on shopping orientation: An exploratory study in Malaysia. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2006, 9, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, S.; Gangadharan, G.R.; Computing, G. Harnessing Green It: Principles and Practices. IT Prof. 2008, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhlayel, M. An Integrative Approach to Develop E-Waste Management Systems for Developing Countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S. Making IT Green. IT Prof. 2010, 12, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostager, T.J.; Neil, T.C.; Decker, R.L.; Lorentz, R.D. Seeing environmental opportunities: Effects of intrapreneurial ability, efficacy, motivation and desirability. J. Organ. Change Manag. 1998, 11, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithas, S.; Khuntia, J.; Roy, P.K. Green Information Technology, Energy Efficiency, and Profits: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. In Proceedings of the 31st ICIS, Saint Louis, MI, USA, 12–15 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, T. Compliance with institutional imperatives on environmental sustainability: Building theory on the role of Green IS. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi-Esfahani, M.; Shahbazi, H.; Nilashi, M. Moderating Effects of Demographics on Green Information System Adoption. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2019, 16, 1950008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of Enterprise Systems: The Effect of Institutional Pressures and the Mediating Role of Top Management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: Testing the structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Lourenço, T.F.; Silva, G.M. Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, X.; Kuang, D.; Hu, Z. The influence factors on young consumers’ green purchase behavior: Perspective based on theory of consumption value. In Proceedings of the 2018 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.C.; Huang, Y.H. The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M.; Suki, N.M. Consumption values and consumer environmental concern regarding green products. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Á.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.R.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, Y.Y. The Impacts of Economic Crisis on Green Consumption in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the PICMET’09-2009 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering & Technology, Portland, OR, USA, 2–6 August 2009; pp. 2367–2374. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J.E. The Impact of Personal Consumption Values and Beliefs on Organic Food Purchase Behavior. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2006, 11, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M.; Suki, N.M. Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: Structural effects of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 132, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, J.M.; Bloom, P.N. Choosing the right green marketing strategy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, P. Investigating factors influencing consumer decision-making while choosing green products. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, J. Applying the Theory of Consumption Values to Choose Behavior toward Green Products. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Conference on Management, Innovation and Technology ICMIT2010, Singapore, 2–5 June 2010; pp. 348–353. [Google Scholar]

- Penz, E.; Stöttinger, B. A comparison of the emotional and motivational aspects in the purchase of luxury products versus counterfeits. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 19, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M.; Suki, N.M. Impact of Consumption Values on Consumer Environmental Concern Regarding Green Products: Comparing Light, Average, and Heavy Users. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 5, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. An Exploratory Assessment of Situational Effects in Buyer Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.; Sharma, B.; Kerr, D.; Smith, T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7684–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.P.; Khandelwal, P.K. Questnr-Can Green Marketing be used as a tool for Sustainable Growth: A Study Performed on Consumers in India- An Emerging Economy. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2010, 6, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Essoo, N.; Dibb, S. Religious Influences on Shopping Behaviour: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, R.E.; Burnett, J.J.; Howell, R.D. On the meaning and measurement of religiosity in consumer research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1986, 14, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, M.B.; Konisky, D.M. The Role of Religion in Environmental Attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 2015, 96, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Ansari, N.Y.; Razzaq, Z.; Awan, H.M. The Impact of Fashion Involvement and Pro-Environmental Attitude on Sustainable Clothing Consumption: The Moderating Role of Islamic Religiosity. SAGE Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrag, D.A.; Hassan, M. The influence of religiosity on Egyptian Muslim youths’ attitude towards fashion. J. Islam. Mark. 2015, 6, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.; Braunsberger, K. I believe therefore I care: The relationship between religiosity, environmental attitudes, and green product purchase in Mexico. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyavooshi, M.; Foroozanfar, A.; Sharifi, Y. Effect of Islamic values on green purchasing behavior. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Shabbir, M.S. The relationship between religiosity and new product adoption. J. Islam. Mark. 2010, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.A. The Relationship between Religiosity and New Product Adoption among Muslim Consumers. Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 2, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, A.K.; Baig, U.K. The Effects of Religiosity on New Product Adoption. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A. Marketing in a multicultural world. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1599–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delener, N. The effects of religious factors on perceived risk in durable goods purchase decisions. J. Consum. Mark. 1990, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, K.S.; Waller, D.S.; Erdogan, B.Z. The influence of religion on attitudes towards the advertising of controversial products. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 537–555. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The Changing Global Religious Landscape: Babies Born to Muslims Will Begin to Outnumber Christian Births by 2035; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huaibin, S.Y.L. Branding Pakistan as a ‘Sufi’ country: The role of religion in developing a nation’s brand. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2014, 7, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-environmental purchase behaviour: The role of consumers’ biospheric values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, T.G.; Boccaccini, M.T. The Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastor. Psychol. 1997, 45, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Phillips, L.W.; Tybout, A.M. Designing Research for Application. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issock, P.B.I.; Mpinganjira, M.; Roberts-Lombard, M. Drivers of consumer attention to mandatory energy-efficiency labels affixed to home appliances: An emerging market perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, A. Our middle class | Opinion | thenews.com.pk | Karachi. THE NEWS, 15 June 2017. Available online: https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/210660-Our-middle-class(accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. Improving your data transformations: Applying Box-Cox transformations as a best practice. Pract. Assessment, Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychlogical. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; ERLBAUM: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hervé, C.; Mullet, E. Age and factors influencing consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama, H.; Rajabpour, S. Factors for consumer choice of dairy products in Iran. Appetite 2017, 111, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew research Center. Event: The Future of World Religions | Pew Research Center. 2015. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/23/live-event-the-future-of-world-religions/ (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- UNEP and Basel Convention. The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous; UNEP and Basel Convention: Basel, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Authors | Country | Context | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | P. C. Lin & Huang | Taiwan | Green Products | The results of this study reveal that consumer choice regarding green products mainly influence by psychological benefit, desire for knowledge, novelty seeking and specific conditions. |

| 2015 | Wen & Noor | Malaysia | Hybrid car | Functional value influenced the intentions towards hybrid car purchasing. While symbolic, novelty and emotional values do not influence the intention. |

| 2015 | Suki & Suki | Malaysia | Green products | Empirical investigation conclude that functional value price, emotional value and conditional value have no significant effects. Social values impact most preceding by epistemic and functional value quality. |

| 2017 | Hassan Rahnama | Iran | Organic products | The study suggested that epistemic value and health value have the highest impact on consumer choice behavior. |

| 2017 | Solaiman et al. | Bangladesh | Environment-friendly and energy efficient Electronics | By taking the corporate image as an additional value the researchers found that corporate image, functional, social, conditional values influence green consumption behavior of environment-friendly and energy efficient electronic products. |

| 2018 | Wang et al. | China | Green Products | This study compares male and female towards green consumption behavior and found female have higher conditional and epistemic value. |

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 320 | 59.7 |

| Female | 216 | 40.3 | |

| Age | 16-24 | 64 | 11.9 |

| 25-34 | 78 | 14.6 | |

| 35-44 | 191 | 35.6 | |

| 45-54 | 114 | 21.3 | |

| 55-64 | 68 | 12.7 | |

| >65 | 21 | 3.9 | |

| Martial | Single | 127 | 23.7 |

| Married | 409 | 76.3 | |

| Education | Intermediate or below | 162 | 30.2 |

| Undergraduate | 215 | 40.1 | |

| Graduate | 106 | 19.8 | |

| Professional | 53 | 9.9 | |

| Occupation | Government Sector | 126 | 23.5 |

| Private Sector | 205 | 38.2 | |

| Self-Employed | 82 | 15.3 | |

| Student | 41 | 7.6 | |

| Retired | 82 | 15.3 | |

| Income | 50,000–75,000 Rs | 162 | 30.2 |

| 75,001–100,000 | 215 | 40.1 | |

| 100,001–125,000 | 106 | 19.8 | |

| 125,001–over | 53 | 9.9 | |

| Green IT product Preferences | Desktop Computer | 44 | 8.2 |

| Printer | 133 | 24.8 | |

| Scanner | 14 | 2.6 | |

| Laptop | 217 | 40.5 | |

| Multimedia Projector | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Communication Systems (Telephone-Intercom) | 51 | 9.5 | |

| Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) | 75 | 14.0 |

| Construct | Item | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Green IT products are good products for the price.” | FV1 | 0.859 | 0.886 | 0.661 |

| “Green IT products are economical for the attributes they offer.” | FV2 | 0.868 | ||

| “Green IT products have an expectable standard quality.” | FV3 | 0.747 | ||

| “Green IT products are made from non-hazardous substances.” | FV4 | 0.771 | ||

| “Buying the green IT product would help me to feel acceptable” | SV1 | 0.752 | 0.845 | 0.578 |

| “Buying the green IT product would improve the way that I am perceived” | SV2 | 0.750 | ||

| “Buying the green IT product would make a good impression on other people” | SV3 | 0.791 | ||

| “Buying the green IT product would give its owner social approval” | SV4 | 0.746 | ||

| “I prefer to check the eco-labels and certifications on green IT products before purchase.” | EPV1 | 0.774 | 0.817 | 0.601 |

| “I would prefer to gain substantial information on green IT products before purchase.” | EPV2 | 0.861 | ||

| “I want to have a deeper insight of the inputs, processes, and impacts of products before purchase” | EPV3 | 0.679 | ||

| “Buying the green IT product instead of conventional products would feel like making a good personal contribution to something better.” | EMV1 | 0.864 | 0.893 | 0.736 |

| “Buying the green IT product instead of conventional products would feel like the morally right thing.” | EMV2 | 0.872 | ||

| “Buying the green IT product instead of conventional products would make me feel like a better person” | EMV3 | 0.837 | ||

| “I would buy the green IT product instead of conventional products under worsening environmental conditions” | CV1 | 0.711 | 0.865 | 0.616 |

| “I would buy the green IT product instead of conventional products when there is a subsidy for green IT products” | CV2 | 0.805 | ||

| “I would buy the green IT product instead of conventional products when there are discount rates for green IT products or promotional activity” | CV3 | 0.822 | ||

| “I would buy the green IT product instead of conventional products when green IT products are available” | CV4 | 0.796 | ||

| “My religious faith is extremely important to me” | RV1 | 0.787 | 0.864 | 0.516 |

| “I look to my faith as a source of inspiration” | RV2 | 0.664 | ||

| “I look to my faith as providing meaning and purpose in my life” | RV3 | 0.669 | ||

| “My faith is an important part of who I am as a person” | RV4 | 0.670 | ||

| “My relationship with God is extremely important to me” | RV5 | 0.803 | ||

| “My faith impacts many of my decisions” | RV6 | 0.703 | ||

| “I will consider buying green IT products.” | IN1 | 0.818 | 0.917 | 0.734 |

| “I plan to switch to other brands/versions of green IT products that are more energy efficient.” | IN2 | 0.863 | ||

| “I intend to buy green IT products.” | IN3 | 0.901 | ||

| “I will buy green IT products in my next purchase.” | IN4 | 0.842 |

| CV | EMV | EPV | FV | IN | RV | SV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | 0.785 | ||||||

| EMV | 0.045 | 0.858 | |||||

| EPV | 0.318 | 0.348 | 0.775 | ||||

| FV | 0.428 | 0.196 | 0.759 | 0.813 | |||

| IN | 0.366 | 0.308 | 0.509 | 0.554 | 0.857 | ||

| RV | 0.405 | 0.098 | 0.454 | 0.579 | 0.676 | 0.719 | |

| SV | 0.324 | 0.213 | 0.348 | 0.421 | 0.466 | 0.514 | 0.760 |

| Intention to Adopt Green IT | |

|---|---|

| Functional value | 2.986 |

| Social value | 1.462 |

| Epistemic value | 2.614 |

| Emotional value | 1.187 |

| Conditional value | 1.302 |

| Religious value | 1.794 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | t Value | p-Value | Supported | R2 | Q2 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | FV→IN | 0.098 | 0.056 | 1.763 | 0.039 | Yes | 0.553 | 0.375 | 0.007 |

| H2 | SV→IN | 0.079 | 0.036 | 2.204 | 0.014 | Yes | 0.010 | ||

| H3 | EPV→IN | 0.101 | 0.049 | 2.080 | 0.019 | Yes | 0.009 | ||

| H4 | EMV→IN | 0.186 | 0.035 | 5.327 | 0.000 | Yes | 0.065 | ||

| H5 | CV→IN | 0.060 | 0.034 | 1.752 | 0.040 | Yes | 0.006 | ||

| H6 | RV→IN | 0.490 | 0.038 | 12.86 | 0.000 | Yes | 0.299 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, S.; Danish, M.; Khuwaja, F.M.; Sajjad, M.S.; Zahid, H. The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values. Environments 2019, 6, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6050053

Ali S, Danish M, Khuwaja FM, Sajjad MS, Zahid H. The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values. Environments. 2019; 6(5):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6050053

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Saqib, Muhammad Danish, Faiz Muhammad Khuwaja, Muhammad Shoaib Sajjad, and Hasan Zahid. 2019. "The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values" Environments 6, no. 5: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6050053

APA StyleAli, S., Danish, M., Khuwaja, F. M., Sajjad, M. S., & Zahid, H. (2019). The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values. Environments, 6(5), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6050053