Lagged and Temperature-Dependent Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on COPD Hospitalizations in Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

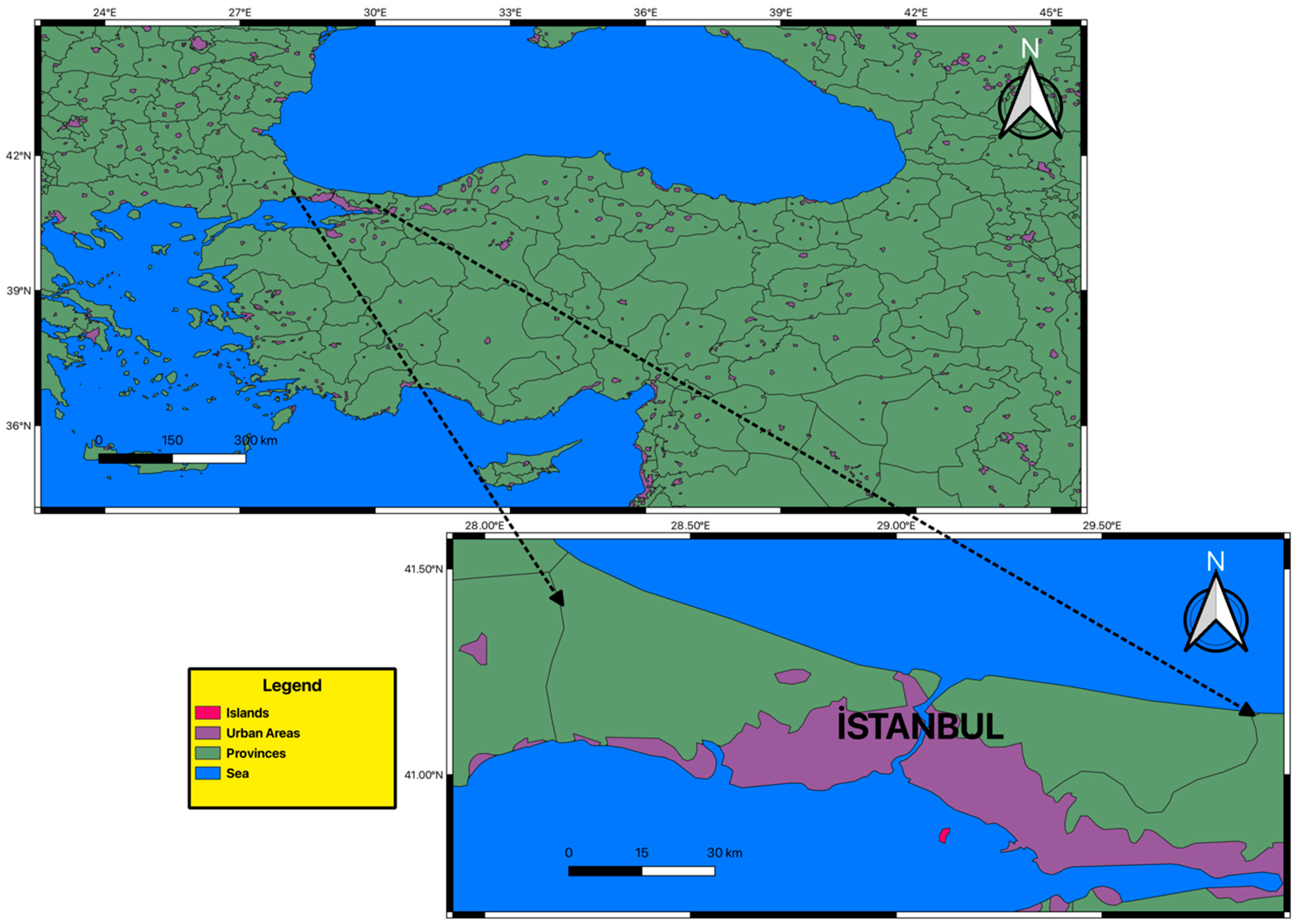

2.1. Study Area and Data

2.2. DLNM Model

3. Results and Discussion

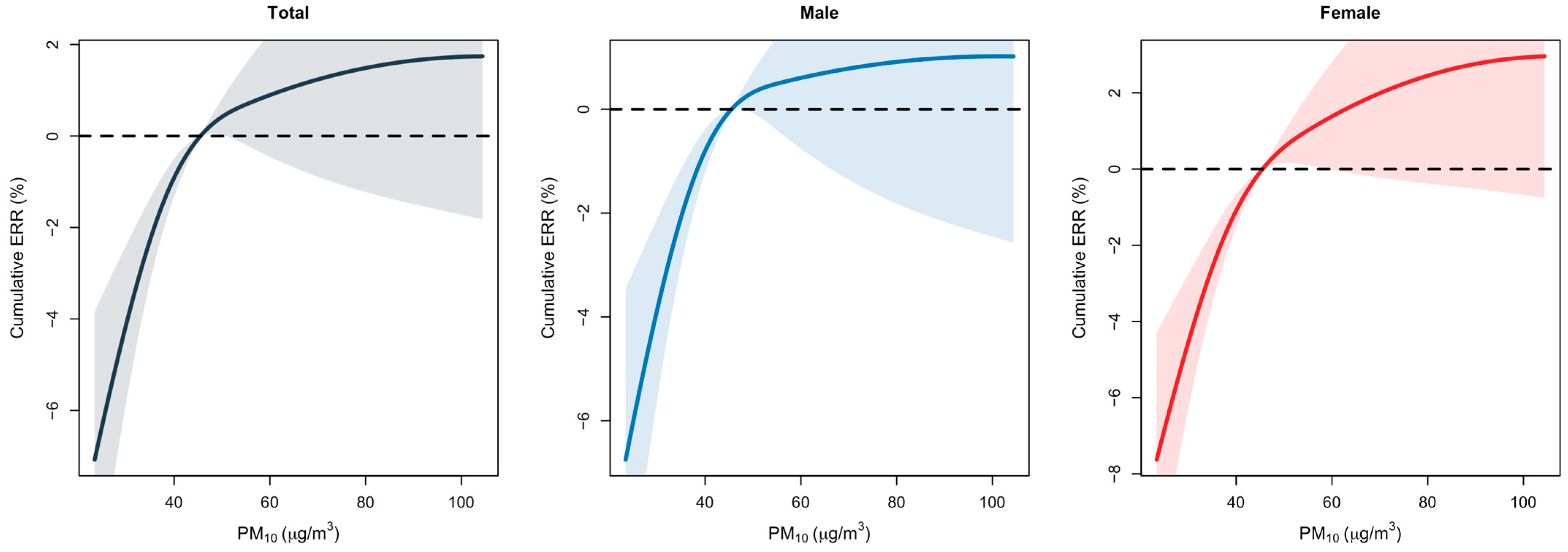

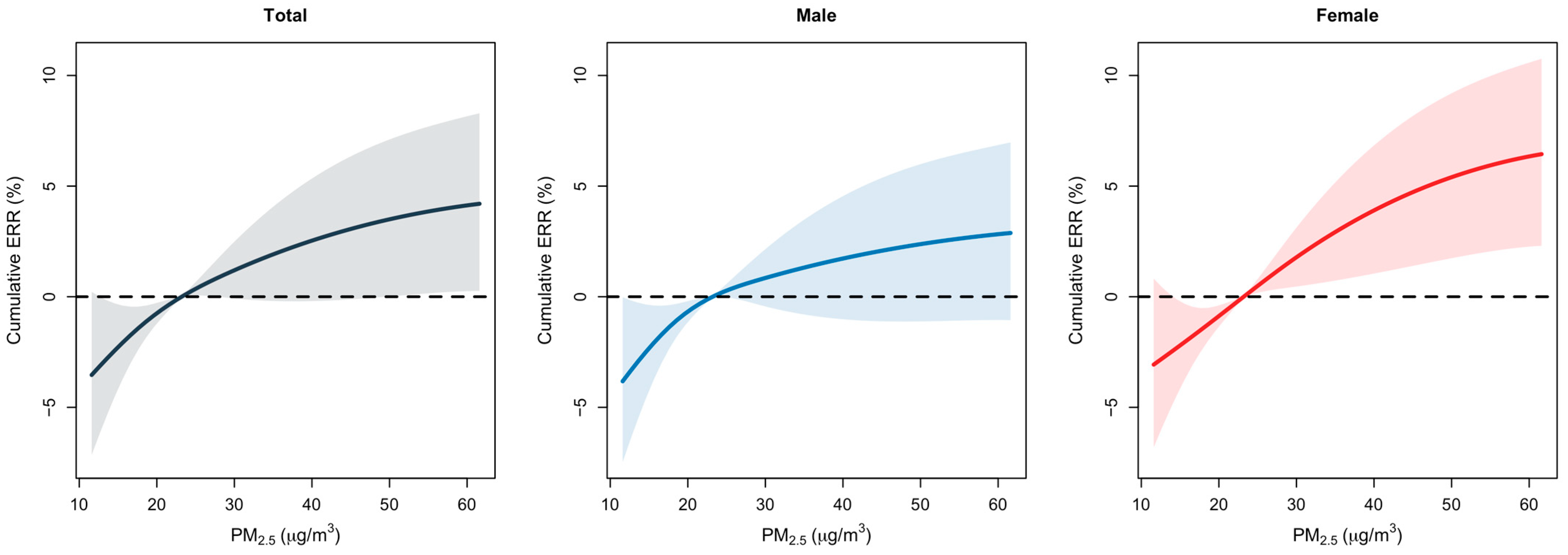

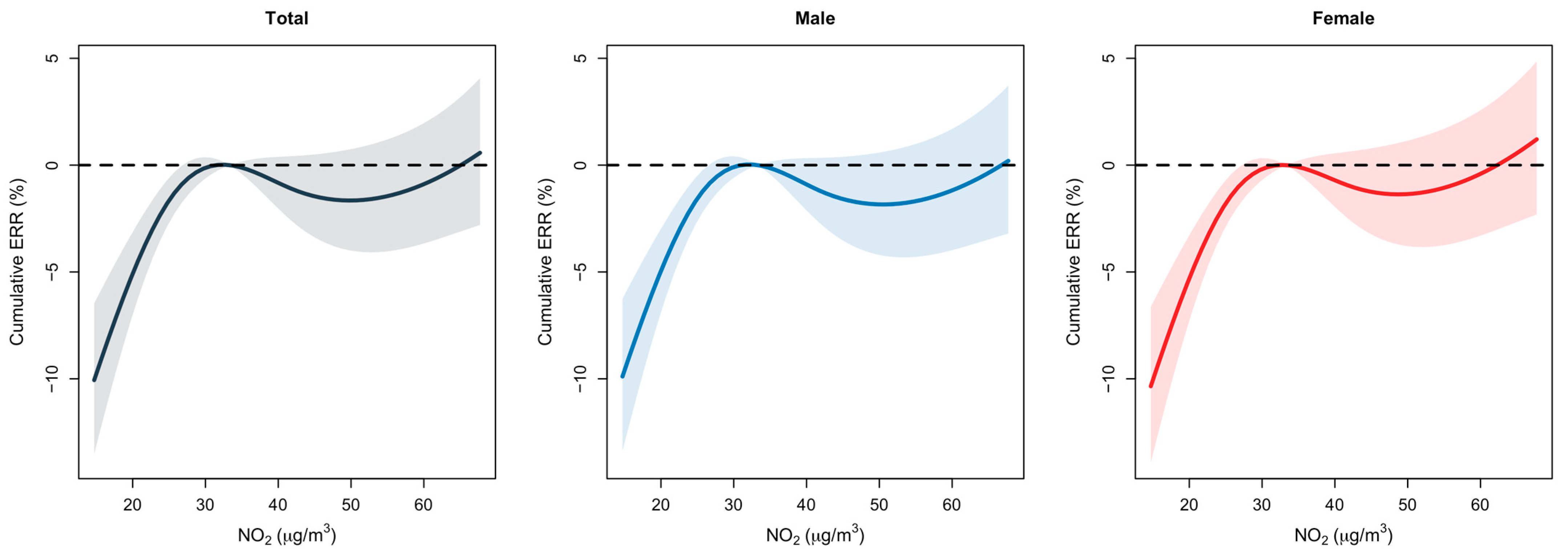

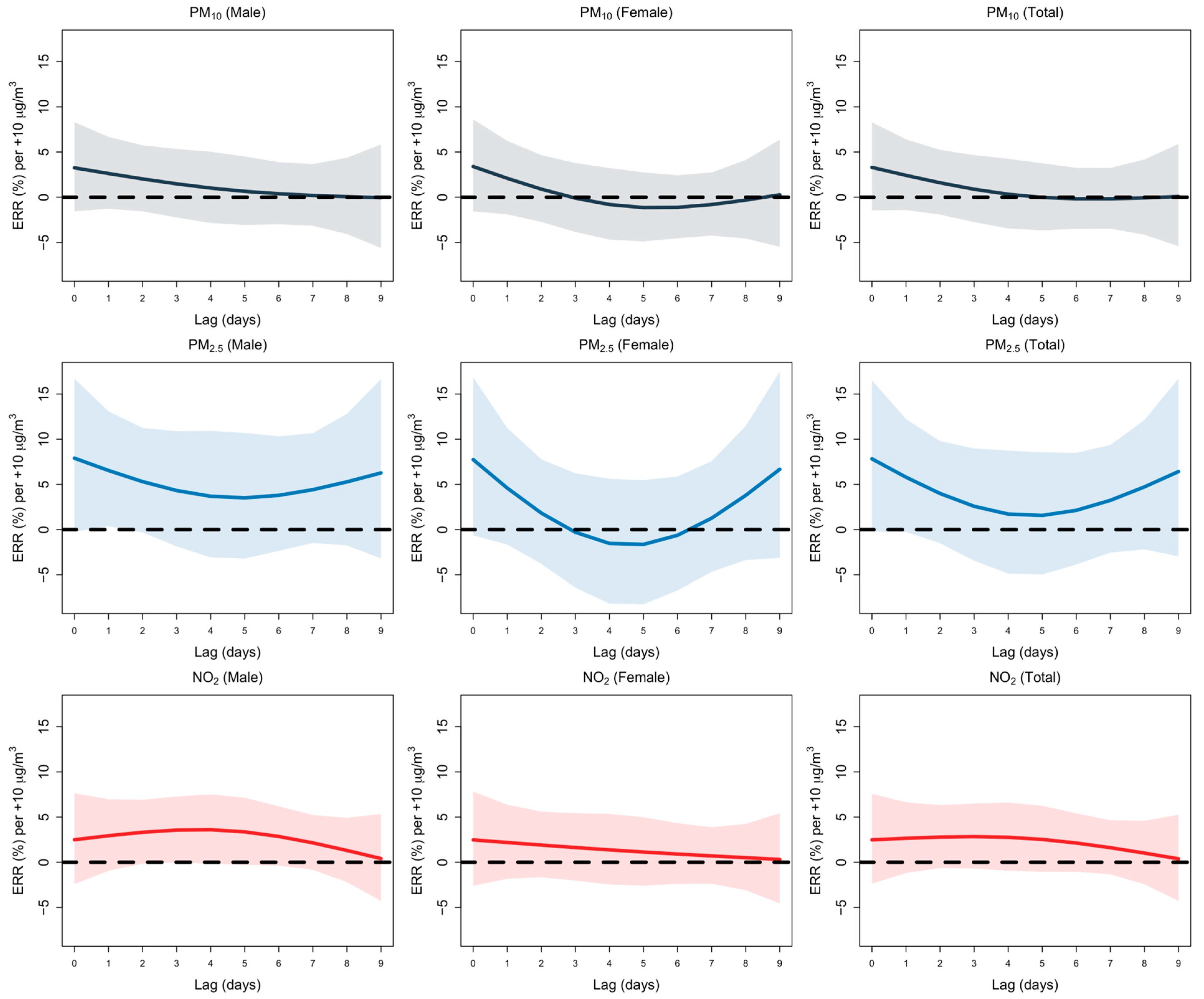

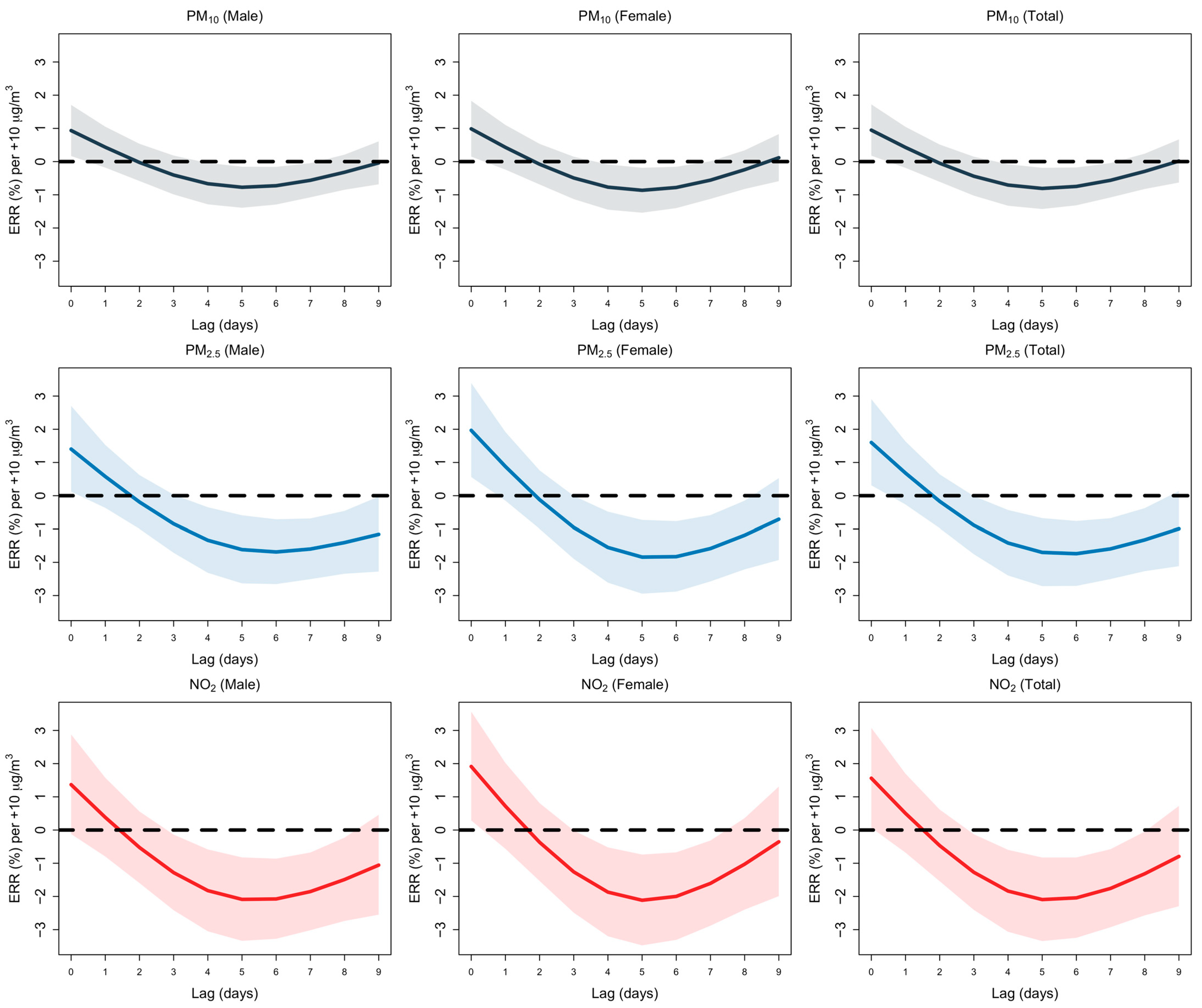

3.1. Lag Analysis

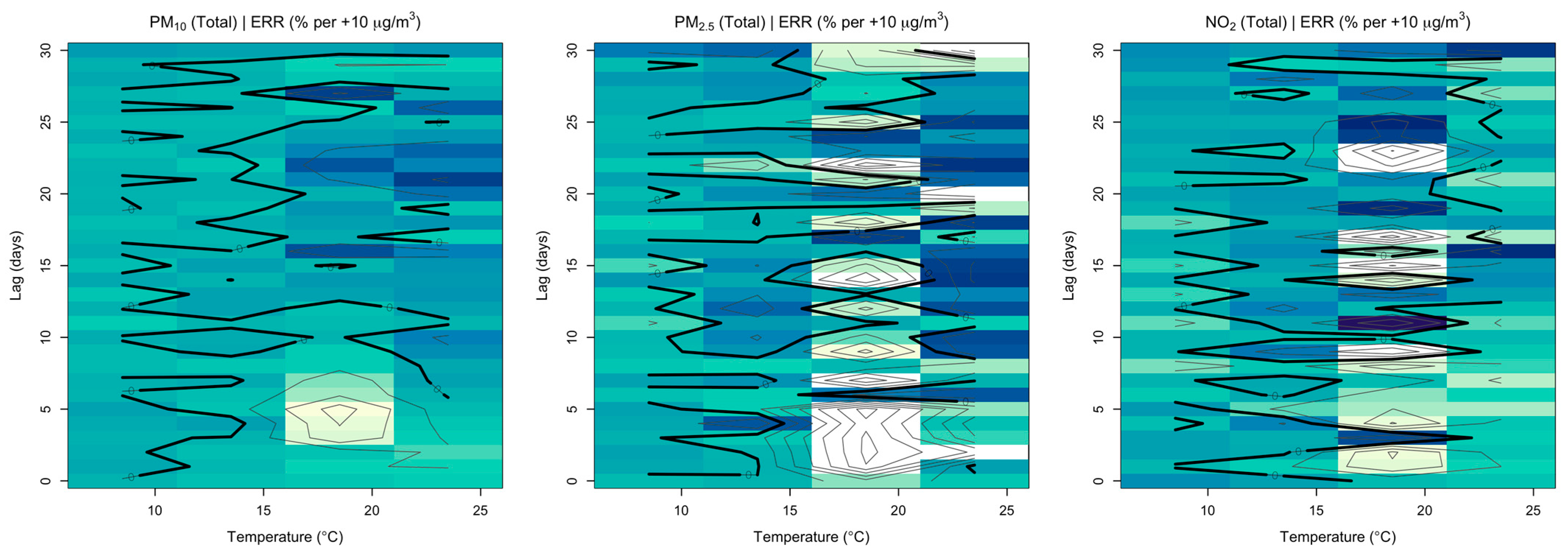

3.2. Seasonal Analysis and Temperature Effects

3.3. Summer Months

3.4. Winter Months

3.5. Temperature Effects

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.N.; Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ambient (Outdoor) Air Quality and Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Miller, M.R.; Newby, D.E. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: Car sick. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Anderson, H.R.; Frostad, J.; Estep, K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Brunekreef, B.; Dandona, L.; Dandona, R.; et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 2017, 389, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, H.; Alemdar, C.S.O.; Akkoyunlu, B.O. Background atmospheric conditions of high PM10 concentrations in Istanbul, Turkey. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, M.; Theodosi, C.; Zarmpas, P.; Im, U.; Bougiatioti, A.; Yenigun, O.; Mihalopoulos, N. Particulate matter (PM10) in Istanbul: Origin, source areas and potential impact on surrounding regions. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6891–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesgin, U.; Vardar, N. A study on exhaust gas emissions from ships in Turkish Straits. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, S.; Tang, R.; Qiu, H.; Huang, Q.; Mason, T.G.; Tian, L. Major air pollutants and risk of COPD exacerbations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 11, 3079–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çapraz, Ö.; Deniz, A.; Doğan, N. Effects of air pollution on respiratory hospital admissions in İstanbul, Turkey, 2013 to 2015. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Wu, S.-M.; Kou, H.-Y.; Chen, K.-Y.; Chuang, H.-C.; Feng, P.-H.; Chung, K.F.; Ito, K.; Chen, T.-T.; Sun, W.-L.; et al. Association of air pollution exposure with exercise-induced oxygen desaturation in COPD. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Ismail, M.; Fong, S.Y. Multiple linear regression (MLR) models for long term PM10 concentration forecasting during different monsoon seasons. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2017, 12, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, H. Air pollution-related deaths in Europe—Time for action. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.G.; Apte, J.S.; Lipsitt, J.; Garcia-Gonzales, D.A.; Beckerman, B.S.; de Nazelle, A.; Jerrett, M. Populations potentially exposed to traffic-related air pollution in seven world cities. Environ. Int. 2015, 78, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekince, B.; Baccioglu, A. Allergic and non-allergic asthma phenotypes and exposure to air pollution. J. Asthma 2022, 59, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Andersen, Z.J.; Beelen, R.; Samoli, E.; Stafoggia, M.; Weinmayr, G.; Hoffmann, B.; Fischer, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Brunekreef, B.; et al. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: Prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, C.; Kang, J.; Ran, P.; Shen, H.; Wen, F.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health [CPH] study): A national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2018, 391, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997, 349, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Jun, K.; Lee, J.Y. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of respiratory related hospitalizations in older patients with COPD, asthma, and bronchiectasis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.D.; Elgaddal, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults age 18 and older: United States, 2023. In NCHS Data Briefs; National Center for Health Statistics (US): Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, J.B.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abera, S.F.; Agrawal, A.; Ahmed, M.B.; Aichour, A.N.; Aichour, I.; Aichour, M.T.E.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desqueyroux, H.; Pujet, J.C.; Prosper, M.; Le Moullec, Y.; Momas, I. Effects of Air Pollution on Adults with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch. Environ. Health Int. J. 2002, 57, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Zou, W.; Zhao, D.; Li, X.; Pu, J.; Huang, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Association between exposure to ambient particulate matter and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Results from a cross-sectional study in China. Thorax 2017, 72, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, D.; de Hoogh, K.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Fortier, I.; Cai, Y.; De Matteis, S.; Hansell, A.L. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: Results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1802140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Peng, C.; Yu, S.; Pei, Y.; Liu, N.; Wu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Cheng, J. Association between PM2.5 Exposure and All-Cause, Non-Accidental, Accidental, Different Respiratory Diseases, Sex and Age Mortality in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasdagli, M.-I.; Katsouyanni, K.; de Hoogh, K.; Lagiou, P.; Samoli, E. Investigating the association between long-term exposure to air pollution and greenness with mortality from neurological, cardio-metabolic and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in Greece. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Tian, Q.; Xu, R.; Zhong, C.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Short-term exposure to ambient air pollution and pneumonia hospital admission among patients with COPD: A time-stratified case-crossover study. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.; Baltaci, H.; Sahin, U.A.; Onat, B. The relationship between air pollutants and respiratory diseases for the western Turkey. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentese, S.; Ogurtani, S.Ö. Spatial and temporal look at ten-years air quality of Istanbul city. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, V. Unveiling the impact of temperature inversions on air quality: A comprehensive analysis of polluted and severe polluted days in Istanbul. Acta Geophys. 2024, 73, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Transportation Statistics; Turkish Statistical Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2022.

- Çolak, Y.; Afzal, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Vestbo, J.; Lange, P. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Prognosis of Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Salcedo, P.; Divo, M.; Casanova, C.; Pinto-Plata, V.; de-Torres, J.P.; Cote, C.; Cabrera, C.; Zagaceta, J.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Zulueta, J.J.; et al. Disease progression in young patients with COPD: Rethinking the Fletcher and Peto model. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, E.K.; Chapman, H.A.; Drazen, J.M.; Weiss, S.T.; Rosner, B.; Campbell, E.J.; O’donnell, W.J.; Reilly, J.J.; Ginns, L.; Mentzer, S.; et al. Genetic Epidemiology of Severe, Early-onset Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. EU Air Quality Standards. 2024. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/air/air-quality/eu-air-quality-standards_en (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- IMM. Air Quality Assessment and Management Regulation. 2024. Available online: https://havakalitesi.ibb.gov.tr/Icerik/mevzuat (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Birinci, E.; Deniz, A.; Özdemir, E.T. The relationship between PM10 and meteorological variables in the mega city Istanbul. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, E.; Özdemir, E.T.; Deniz, A. An investigation of the effects of sand and dust storms in the North East Sahara Desert on Turkish airports and PM10 values: 7 and 8 April, 2013 events. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapraz, Ö.; Deniz, A. Particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) concentrations during a Saharan dust episode in Istanbul. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summak, G.; Özdemir, H.; Oruç, İ.; Kuzu, S.; Saral, A.; Demir, G. Statistical evaluation and predicting the possible sources of particulate matter in a Mediterranean metropolitan city. Glob. NEST J. 2018, 20, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini, A.; Armstrong, B.; Scheipl, F. R Package, version 1.1. dlnm: Distributed Lag Non-Linear Models. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- López, A.B.H.; Torres-Duque, C.A.; Arbeláez, M.P.; Roa, N.Y.R.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Sangrador, J.L.T.; Herrera, V.; Rodríguez-Villamizar, L.A. Short-term effect of air pollution exposure on COPD exacerbations: A time series study in Bogota, Colombia. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 2775–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, H.; Kollanus, V.; Tiittanen, P.; Mikkonen, S.; Lipponen, A.H.; Zhang, S.; Breitner, S.; Schneider, A.; Lanki, T. Low temperature, cold spells, and cardiorespiratory hospital admissions in Helsinki, Finland. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2023, 16, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapraz, Ö. The impact of air temperature on mortality in İstanbul. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2025, 69, 3351–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.M.; Chen, Y.T.; Ou, S.M.; Hsiao, Y.H.; Li, S.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Yang, A.C.; Chen, T.-J.; Perng, D.W. The effect of cold temperature on increased exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A nationwide study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, M.C.; Belli, A.J.; Waugh, D.; Matsui, E.C.; Peng, R.D.; Williams, D.A.L.; Paulin, L.; Saha, A.; Aloe, C.M.; Diette, G.B.; et al. Respiratory effects of indoor heat and the interaction with air pollution in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; He, J. Long-term effects of ambient air pollution on lung cancer and COPD mortalities in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becklake, M.R.; Kauffmann, F. Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 1999, 54, 1119–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCracken, J.P.; Smith, K.R.; Díaz, A.; Mittleman, M.A.; Schwartz, J. Chimney Stove Intervention to Reduce Long-term Wood Smoke Exposure Lowers Blood Pressure among Guatemalan Women. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Wang, C.; Cao, D.; Wong, C.-M.; Kan, H. Short-term effect of ambient air pollution on COPD mortality in four Chinese cities. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, H.; Goudarzi, G.; Jalali, S.; Barzegar, G.; Farhadi, M.; Parseh, I.; Geravandi, S.; Salmanzadeh, S.; Yousefi, F.; Mohammadi, M.J. Study of relationship between nitrogen dioxide and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Bushehr, Iran. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Qin, C.; Qiu, H.; Tarroni, G.; Duan, J.; Bai, W.; Rueckert, D. Deep learning for cardiac image segmentation: A review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, R.; Dos Santos, S.G.; Borge, R.; de la Paz, D.; Sarigiannis, D.; Gotti, A.; Boldo, E. Health impact assessment by the implementation of Madrid City air-quality plan in 2020. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, G.; Krishnan, R.M.; Beelen, R.; Peters, A.; Ostro, B.; Brunekreef, B.; Kaufman, J.D. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio-respiratory mortality: A review. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motesaddi Zarandi, S.; Hadei, M.; Hashemi, S.S.; Shahhosseini, E.; Hopke, P.K.; Namvar, Z.; Shahsavani, A. Effects of ambient air pollutants on hospital admissions and deaths for cardiovascular diseases: A time series analysis in Tehran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 17997–18009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, E.; Denizoğlu, M.; Özdemir, H.; Özdemir, E.T.; Deniz, A. Ambient air quality assessment at the airports based on a meteorological perspective. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clougherty, J.E. A Growing Role for Gender Analysis in Air Pollution Epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Han, C.; Fang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chi, X.; Li, X. Associations between air pollutants and hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Jinan: Potential benefits from air quality improvements. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 46435–46445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Maglakelidze, M.; von Schneidemesser, E.; Witt, C.; Hoffmann, P.; Butler, T. Asthma and COPD exacerbation in relation to outdoor air pollution in the metropolitan area of Berlin, Germany. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinoudis, G.; Minelli, C.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Ballester, J.; Gasparrini, A.; Blangiardo, M. Ambient heat exposure and COPD hospitalisations in England: A nationwide case-crossover study during 2007–2018. Thorax 2022, 77, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, A.; Aichner, M.; Sonnweber, T.; Tancevski, I.; Fischer, T.; Sahanic, S.; Joannidis, M.; Weiss, G.; Pizzini, A.; Loeffler-Ragg, J. COPD exacerbations are related to poor air quality in Innsbruck: A retrospective pilot study. Heart Lung 2021, 50, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Ramón, M.; Schwartz, J. Temperature, temperature extremes, and mortality: A study of acclimatisation and effect modification in 50 US cities. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 64, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklöv, J.; Forsberg, B. The effect of temperature on mortality in Stockholm 1998—2003: A study of lag structures and heatwave effects. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, L.; Xin, L.; Pi, F.; Dong, W.; Wen, Y.; Au, W.W.; Zhang, Q. High diurnal temperature range and mortality: Effect modification by individual characteristics and mortality causes in a case-only analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Ramírez, I.; Rocha Amador, D.O.; López Gutiérrez, J.M.; Ramírez Mosqueda, E.; Cea Barcia, G.E.; Ramos Patlán, F.D.; Costilla Salazar, R. Chemical Characterization and Assessment of Public Health Risk due to Inhalation of PM2.5 in the City of Salamanca, Guanajuato. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 113, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Dong, J. Association between air pollution and hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A time series analysis in Dingxi, China, 2018–2020. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Fang, S.; Nan, Y.; Hu, J.; Jin, H. The effect of air pollutants on COPD-hospitalized patients in Lanzhou, China (2015–2019). Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1399662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Jiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, B.; Feng, F.; Yu, Z.; Ma, B. Impact of temperature changes between neighboring days on COPD in a city in Northeast China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 4849–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, L.; Ye, X.; Yang, D.; Yang, S.; Zhou, J.; Luo, B. Interactive effects of high temperature and ozone on COPD deaths in Shanghai. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 278, 119092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, P.; Schwarz, M.; Mikušová, M. Assessment of Health Risks Associated with PM10 and PM2. 5 Air Pollution in the City of Zvolen and Comparison with Selected Cities in the Slovak Republic. Environments 2025, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, B.; Jankowski, M.; Wieczorek, J.; Gruszczyńska, M.; Sekuła, P.; Jaczewski, A.; Wyszogrodzki, A.; Pinkas, J.; Figurski, M. The impact of ambient air pollution and meteorological factors on emergency hospital admissions of COPD patients in Poland (2012–2019). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Year | Location | Method | Sample | Health Effects | Outcome (Odds Ratio (OR)/Hazard Ratio (HR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | China (2012–2015) | Cross-sectional study | 5993 | prevalence | PM concentration levels: 2.416 (95% CI,1.417 to 4.118) for >35–75 μg/m3 and 2.530 (95% CI, 1.280 to 5.001) for >75 μg/m3 compared with the level of ≤35 μg/m3 for PM2.5 2.442 (95% CI, 1.449 to 4.117) for >50–150 μg/m3 compared with the level of ≤50 μg/m3 for PM10 |

| [24] | UK (2006–2010) | Cross-sectional analyses | 303,887 | prevalence | PM2.5 (1.52, 95% CI 1.42–1.62, per 5 μg/m3) PM10 (1.08, 95% CI 1.00–1.16, per 5 μg/m3) NO2 (1.12, 95% CI 1.10–1.14, per 10 μg/m3) |

| [25] | China (2013–2015) | Time-series study | 41,815 | mortality | The excess risk (ER) is 8.24% (95% CI: 3.53–13.17) for a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 |

| [26] | Greece (2010–2011) | two-exposure Poisson regression models | - | mortality | 1.14, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01, 1.28) for PM2.5; 1.03 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.07) for NO2; 1.05 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.10 for BC), respectively, and from cerebrovascular disease (RR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.18 for PM2.5); 1.02 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.04 for NO2); 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.04 for BC), respectively). |

| [27] | China (2016–2019) | crossover design | 6473 | prevalence | The study found that exposure to PM2.5 (lag 2; IQR, 22.1 μg/m3), SO2 (lag 03; IQR, 4.2 μg/m3), NO2 (lag 03; IQR, 21.4 μg/m3), and O3 (lag 04; IQR, 57.9 μg/m3) was linked to an increased odds ratio of pneumonia HA. Specifically, the odds ratios for PM2.5, SO2, NO2, and O3 were 1.043 (95% CI: 1.004–1.083), 1.081 (95% CI: 1.026–1.140), 1.045 (95% CI: 1.005–1.088), and 1.080 (95% CI: 1.018–1.147), respectively. |

| Mean ± SD | Min | P (25) | P (50) | P (75) | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 786,290) | 588 ± 379 | 14 | 88 | 479 | 871 | 1372 |

| Male (n = 483,859) | 368 ± 237 | 11 | 56 | 300 | 544 | 850 |

| Female (n = 302,431) | 221 ± 143 | 3 | 32 | 181 | 331 | 551 |

| Air Pollution Concentrations (µg/m3) | ||||||

| PM10 | 52.4 ± 26.6 | 12.6 | 35 | 49.5 | 65.03 | 297.1 |

| PM2.5 | 27.9 ± 16.8 | 6.1 | 16.8 | 25.6 | 34.4 | 116.8 |

| NO2 | 36.2 ± 16.52 | 8.8 | 22.7 | 35.3 | 48.9 | 93.14 |

| Meteorological Variables | ||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 14.9 ± 6.7 | −3.5 | 9.4 | 15.6 | 20.9 | 27.7 |

| Relative Humidity (%) | 78.2 ± 11.4 | 47.2 | 71.2 | 79.5 | 86.4 | 100 |

| Lag | PM10 (Lower 95% CI) | PM10 (Estimate) | PM10 (Upper 95% CI) | PM2.5 (Lower 95% CI) | PM2.5 (Estimate) | PM2.5 (Upper 95% CI) | NO2 (Lower 95% CI) | NO2 (Estimate) | NO2 (Upper 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | L0 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 0.9 | 0.99 | 1.1 |

| L1 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.8 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.26 | |

| L2 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.9 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 1.2 | |

| L3 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 1.05 | |

| L4 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.97 | |

| L5 | 0.9 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.9 | 0.97 | |

| L6 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 1.02 | |

| L7 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 1.11 | |

| L8 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 1.13 | |

| L9 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 1 | |

| Male | L0 | 0.45 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 1.1 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 1.05 | 1.19 |

| L1 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.1 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 1.31 | |

| L2 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 1.21 | |

| L3 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.97 | 1.04 | |

| L4 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.11 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.97 | |

| L5 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.2 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.8 | 0.88 | 0.07 | |

| L6 | 0.85 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 1.02 | |

| L7 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 1.11 | |

| L8 | 0.66 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.13 | |

| L9 | 0.6 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 1.04 | |

| Female | L0 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 1.17 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 1.06 |

| L1 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.26 | 0.97 | 1.12 | 1.3 | |

| L2 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.24 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 1.29 | |

| L3 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.11 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.13 | |

| L4 | 0.9 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.07 | |

| L5 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 1.07 | |

| L6 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 1.12 | |

| L7 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.21 | |

| L8 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.21 | |

| L9 | 0.69 | 1 | 1.43 | 0.87 | 1 | 1.15 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 1.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Birinci, E.; Çeker, A.O.; Çapraz, Ö.; Özdemir, H.; Deniz, A. Lagged and Temperature-Dependent Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on COPD Hospitalizations in Istanbul. Environments 2026, 13, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010056

Birinci E, Çeker AO, Çapraz Ö, Özdemir H, Deniz A. Lagged and Temperature-Dependent Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on COPD Hospitalizations in Istanbul. Environments. 2026; 13(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleBirinci, Enes, Ali Osman Çeker, Özkan Çapraz, Hüseyin Özdemir, and Ali Deniz. 2026. "Lagged and Temperature-Dependent Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on COPD Hospitalizations in Istanbul" Environments 13, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010056

APA StyleBirinci, E., Çeker, A. O., Çapraz, Ö., Özdemir, H., & Deniz, A. (2026). Lagged and Temperature-Dependent Effects of Ambient Air Pollution on COPD Hospitalizations in Istanbul. Environments, 13(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010056