Water Quality, Environmental Contaminants and Disease Burden in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Associations with Disability-Adjusted Life Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Dataset Building

2.3. Exposure Variables

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Contextual Indexes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

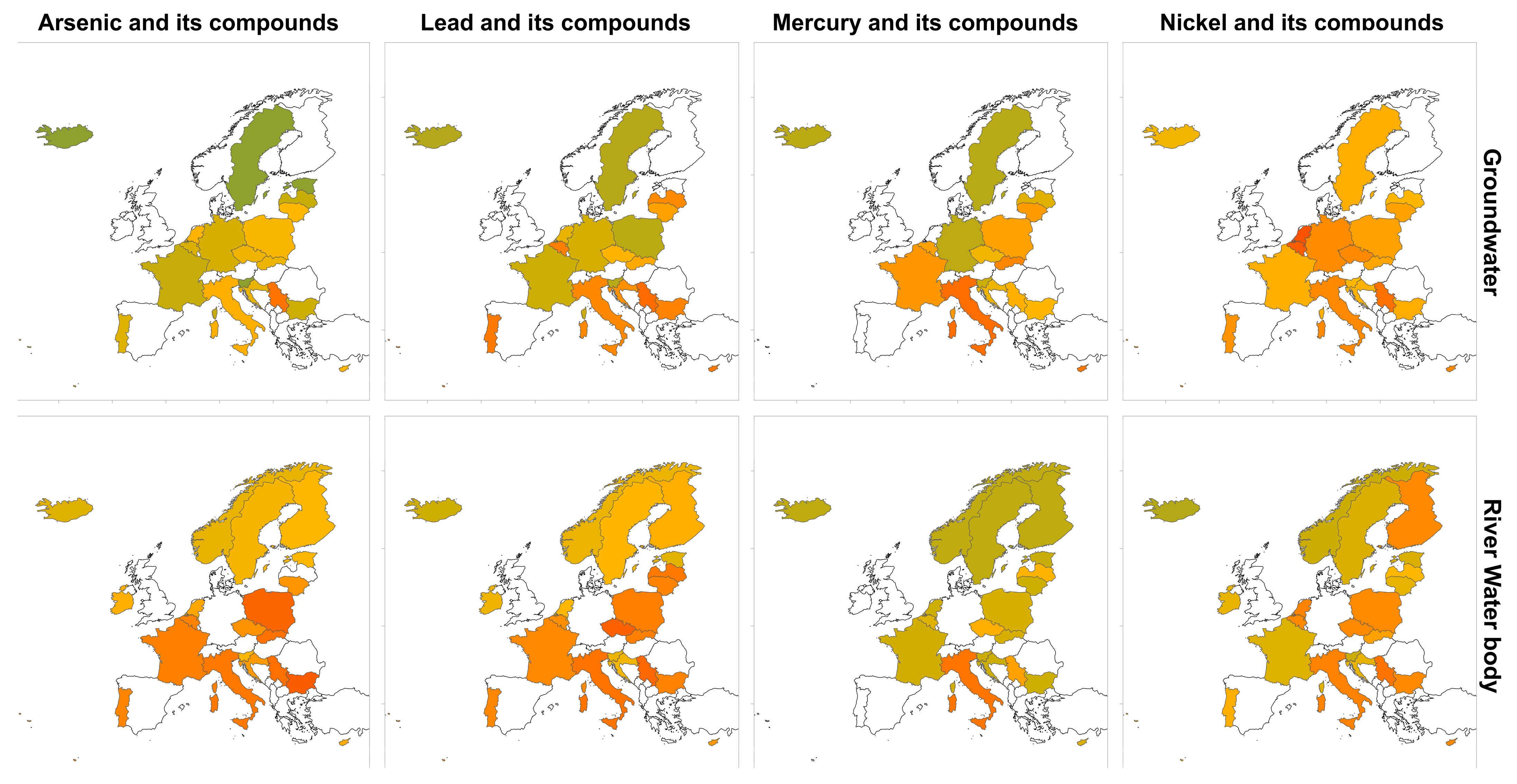

3.1. Data Completeness and Normalized Concentrations

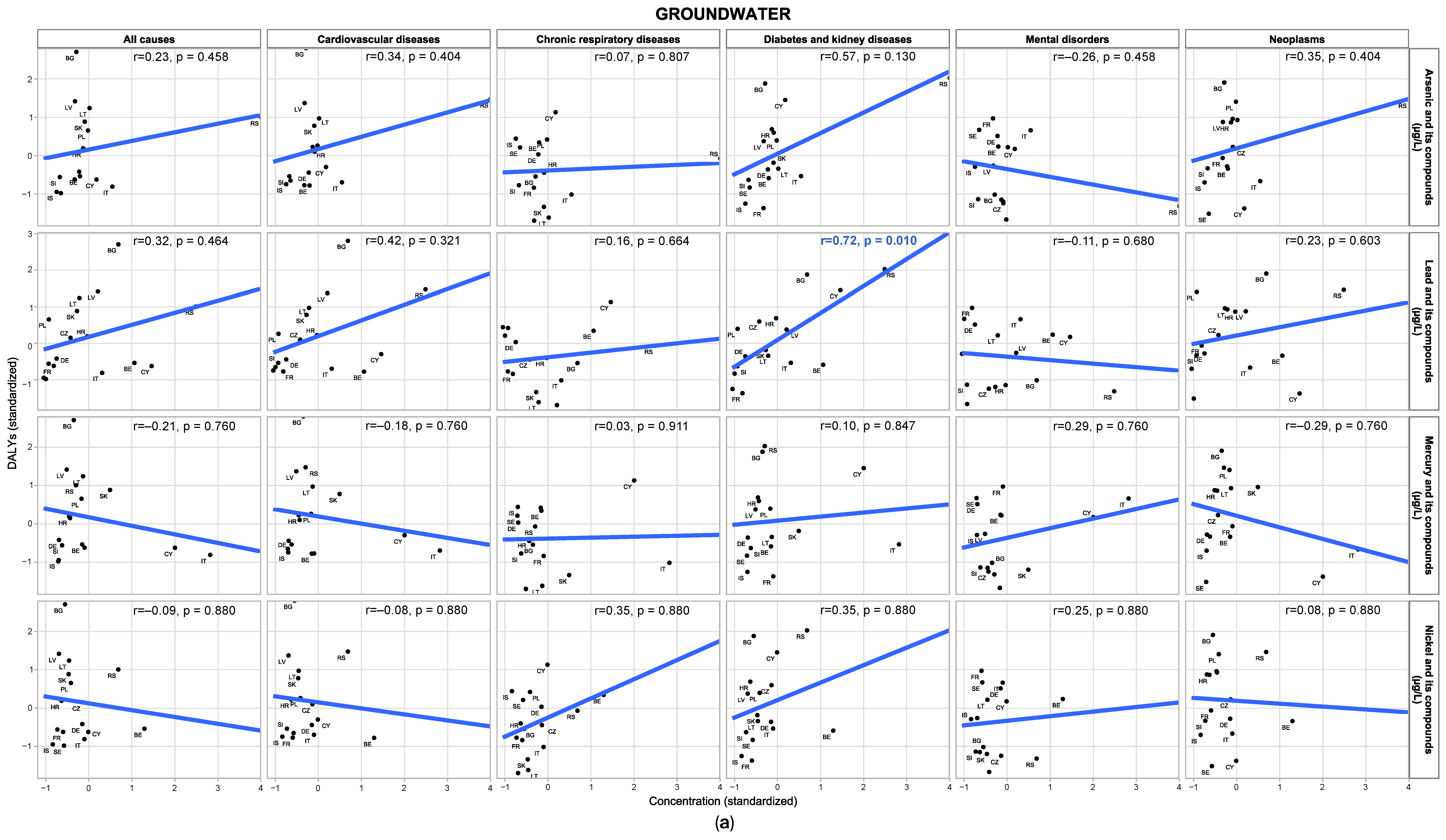

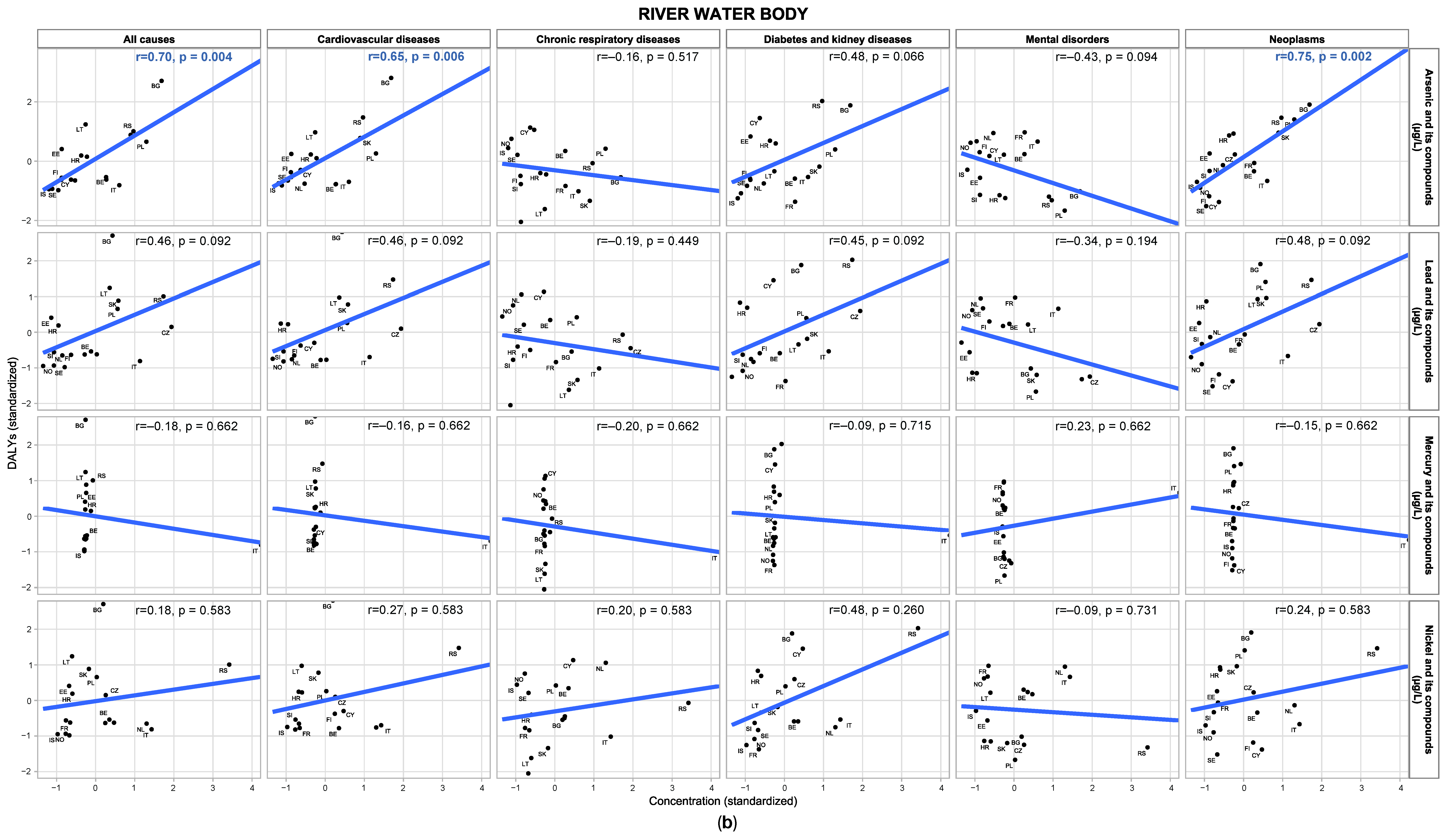

3.2. Crude Correlation Between Water Contaminants and DALY Outcomes

3.3. Associations of Groundwater and River Water Contaminants with Disease Burden

3.4. Associations After Sequential Adjustment for Contextual Indexes

3.4.1. Groundwater

3.4.2. River Water

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with the Existing Literature

4.3. Public Health Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Human Rights to Water and Sanitation in Practice: Findings and Lessons Learned from the Work on Equitable Access to Water and Sanitation Under the Protocol on Water and Health in the Pan-European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Ensuring Clean Waters for People and Nature; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2000/60/EC of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, L327, 1–73. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj/eng (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 6: Ensure Availability and Sustainable Management of Water and Sanitation for All; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hering, D.; Carvalho, L.; Argillier, C.; Beklioglu, M.; Borja, A.; Cardoso, A.C.; Duel, H.; Ferreira, T.; Globevnik, L.; Hanganu, J.; et al. Managing Aquatic Ecosystems and Water Resources under Multiple Stress—An Introduction to the MARS Project. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 503–504, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzetti, B.; Vigiak, O.; Udias, A.; Aloe, A.; Zanni, M.; Bouraoui, F.; Pistocchi, A.; Dorati, C.; Friedland, R.; De Roo, A.; et al. How EU Policies Could Reduce Nutrient Pollution in European Inland and Coastal Waters. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesković, J.; Onjia, A. Environmental Implications of the Soil-to-Groundwater Migration of Heavy Metals in Mining Area Hotspots. Metals 2024, 14, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, R.; Pecyna-Utylska, P.; Kernert, J.; Grygoyć, K.; Klyta, J. Health Risk Assessment of Selected Metals through Tap Water Consumption in Upper Silesia, Poland. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2020, 18, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlati, M.L.; Georgescu, L.P.; Iticescu, C.; Ionescu, R.V.; Antohi, V.M. New Approach to Modelling the Impact of Heavy Metals on the European Union’s Water Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Ortega, A.; Acuña, V.; Bellin, A.; Burek, P.; Cassiani, G.; Choukr-Allah, R.; Dolédec, S.; Elosegi, A.; Ferrari, F.; Ginebreda, A.; et al. Managing the Effects of Multiple Stressors on Aquatic Ecosystems under Water Scarcity. The GLOBAQUA Project. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 503–504, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, R.; Villanueva, C.M.; Beene, D.; Cradock, A.L.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Lewis, J.; Martinez-Morata, I.; Minovi, D.; Nigra, A.E.; Olson, E.D.; et al. US Drinking Water Quality: Exposure Risk Profiles for Seven Legacy and Emerging Contaminants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Effects of Water Pollution on Human Health and Disease Heterogeneity: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 880246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.M.; Romanok, K.M.; Smalling, K.L.; Focazio, M.J.; Evans, N.; Fitzpatrick, S.C.; Givens, C.E.; Gordon, S.E.; Gray, J.L.; Green, E.M.; et al. Bottled Water Contaminant Exposures and Potential Human Effects. Environ. Int. 2022, 171, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payment, P. Health Effects of Water Consumption and Water Quality. In Handbook Water Wastewater Microbiol; Academic Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levallois, P.; Villanueva, C.M. Drinking Water Quality and Human Health: An Editorial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawkes, L.; Sansom, G. Preliminary Study of Lead-Contaminated Drinking Water in Public Parks—An Assessment of Equity and Exposure Risks in Two Texas Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, P.; Fawell, J. Lead in Drinking Water—An Ongoing Public Health Concern? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 20, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, R.; Cronk, R.; Wright, J.; Yang, H.; Slaymaker, T.; Bartram, J. Fecal Contamination of Drinking-Water in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Chowdhury, I.R.; Mazumder, M.A.J.; Al-Suwaiyan, M.S. Predicting Risk and Loss of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) from Selected Disinfection Byproducts in Multiple Water Supply Sources in Saudi Arabia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolofari, D.L.; Bartrand, T.; Haas, C.N.; Olson, M.S.; Gurian, P.L. Disability-Adjusted Life Year Frameworks for Comparing Health Impacts Associated with Mycobacterium Avium, Trihalomethanes, and Haloacetic Acids in a Building Plumbing System. ACS ES&T Water 2022, 2, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Multiple Imputation with Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equation (MICE) Package. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, R.W.; Reed, L.D. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1990, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency Waterbase—Water Quality ICM. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/fbf3717c-cd7b-4785-933a-d0cf510542e1 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Industrial Waste Water Treatment—Pressures on the Environment (EEA Report No 23/2018); European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Europe’s Groundwater—A Key Resource under Pressure (Briefing No. 03/2022); European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp. Suppl. 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri Soodejani, M. Non-Communicable Diseases in the World over the Past Century: A Secondary Data Analysis. Front. Public. Health 2024, 12, 1436236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pandian, V.; Davidson, P.M.; Song, Y.; Chen, N.; Fong, D.Y.T. Burden and Attributable Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases and Subtypes in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 2385–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Maung-U, K.; Jagadeesh, G. Prevalence and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 113, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators (WDI) [Database]; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), 2024 Update; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Collignon, P.; Beggs, J.J.; Walsh, T.R.; Gandra, S.; Laxminarayan, R. Anthropological and Socioeconomic Factors Contributing to Global Antimicrobial Resistance: A Univariate and Multivariable Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e398–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminit, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Pesticides in Rivers, Lakes and Groundwater in Europe; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Technical Report on Groundwater Quality Trend and Trend Reversal Assessment; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Farzana, F.; Roy, T.K.; Hossain, S.A.; Mazrin, M.; Islam, M.S.; Mahiddin, N.A.; Jayoti, J.R.; Ghosh, R.; Al Bakky, A.; Ismail, Z.; et al. Assessment of Groundwater Quality and Potential Health Risks Related to Heavy Metals in a Peri-Urban Area of a Developing Country. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, J.B.; Örmeci, B.; Aw, T.G. Water Quality and Health: An Ecological Perspective. Water Ecol. 2025, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, S.; Birhanu, B.; Tanui, F.; Sule, M.N.; Charles, K.; Olago, D.; Kebede, S. Water Chemistry Poses Health Risks as Reliance on Groundwater Increases: A Systematic Review of Hydrogeochemistry Research from Ethiopia and Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Forcada, E.; Luque-Espinar, J.A.; López-Bahut, M.T.; Grima-Olmedo, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, J.; Ontiveros-Beltranena, C.; Díaz-Muñoz, J.Á.; Elster, D.; Skopljak, F.; Voutchkova, D.; et al. Analysis of the Geological Control on the Spatial Distribution of Potentially Toxic Concentrations of As and F- in Groundwater on a Pan-European Scale. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 247, 114161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentek, Z.; Prtorić, J.; Pilz, S.; Renson, I.; Eckert, M.; Tudela, A.; Delgado, A.; Aubert, R.; Boutsi, M.; Sanchez, L. Under the Surface—The Hidden Crisis in Europe’s Groundwater. Available online: https://europeanwaters.eu/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Zanchi, M.; Zapperi, S.; Zanotti, C.; Rotiroti, M.; Bonomi, T.; Gomarasca, S.; Bocchi, S.; La Porta, C.A.M. A Pipeline for Monitoring Water Pollution: The Example of Heavy Metals in Lombardy Waters. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, R.; Allocca, V.; Coda, S.; Cusano, D.; Fusco, F.; Nicodemo, F.; Pizzolante, A.; De Vita, P. Groundwater Vulnerability of Principal Aquifers of the Campania Region (Southern Italy). J. Maps 2020, 16, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Destouni, G.; Ghajarnia, N.; Kalantari, Z. Soil Degradation in the European Mediterranean Region: Processes, Status and Consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopang, M.; Yazdi, M.D.; Moyer, A.; Smith, D.M.; Meliker, J.R. Low-to-Moderate Arsenic Exposure: A Global Systematic Review of Cardiovascular Disease Risks. Environ. Health 2025, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Graziano, J.H.; Parvez, F.; Liu, M.; Slavkovich, V.; Kalra, T.; Argos, M.; Islam, T.; Ahmed, A.; Rakibuz-Zaman, M.; et al. Arsenic Exposure from Drinking Water and Mortality from Cardiovascular Disease in Bangladesh: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2011, 342, d2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, J.S.; Perez, V.; Garry, M.R.; Alexander, D.D. Association of Low-Level Arsenic Exposure in Drinking Water with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Risk Assessment. Toxicology 2014, 323, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigra, A.E.; Cazacu-De Luca, A.; Navas-Acien, A. Socioeconomic Vulnerability and Public Water Arsenic Concentrations across the US. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, L.; Jin, H. Trends in Global Burden of Diseases Attributable to Lead Exposure in 204 Countries and Territories from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1036398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, J. Association of Urinary and Blood Lead Concentrations with All-Cause Mortality in US Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Liu, C.; Yang, M. The Association between Urinary Lead Concentration and the Likelihood of Kidney Stones in US Adults: A Population-Based Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Geetha, P.; Kyriazis, P.; Specht, A.; Hu, H.; Danziger, J. Association of Environmental Lead Toxicity and Hematologic Outcomes in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 1337–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gao, X.; Huo, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, Z. Lead Exposure Aggravates Glucose Metabolism Disorders through Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Intestinal Barrier Damage in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwa, R.R.; Deocaris, C.C.; Geraldo, L.D.; Belo, L.P. Ecological and Health Risks from Heavy Metal Sources Surrounding an Abandoned Mercury Mine in the Island Paradise of Palawan, Philippines. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Carocci, A.; Lauria, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Catalano, A. Nickel: Human Health and Environmental Toxicology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town, R.M.; Peters, A.; Cooper, C. Importance of Chemical Speciation and Bioavailability in Hazard Assessment, Risk Assessment and Regulation of Metals in Multi-Stressor Environmental Conditions. Available online: https://www.setac.org/resource/importance-of-chemical-speciation-and-bioavailability-in-hazard-assessment-risk-assessment-and-regulation-of-metals-in-multi-stressor-environmental-conditions.html (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Tota, M.; Karska, J.; Kowalski, S.; Piątek, N.; Pszczołowska, M.; Mazur, K.; Piotrowski, P. Environmental Pollution and Extreme Weather Conditions: Insights into the Effect on Mental Health. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1389051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liang, X.; Xia, L.; Yu, S.; Wu, F.; Li, M. Association between Air Pollutants and Four Major Mental Disorders: Evidence from a Mendelian Randomization Study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G.S.; Zeka, A.; Ashworth, M.; Bouland, C.; Crabbe, H.; Duarte-Davidson, R.; Etzel, R.A.; Giuashvili, N.; Gökdemir, Ö.; Hanke, W.; et al. A New Environmental Public Health Practice to Manage Current and Future Global Health Challenges through Education, Training, and Capacity Building. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1373490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; White, P.C.L. Social Determinants and Lifestyles: Integrating Environmental and Public Health Perspectives. Public Health 2016, 141, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, F.; Buzzoni, C.; Russo, A.G.; Gervasi, F.; Braga, M.; Renzi, C. Comorbidities, Socioeconomic Status, and Colorectal Cancer Diagnostic Route. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e258867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, C.; Pennisi, F.; Lunetti, C.; Blandi, L.; Pellissero, G.; Fondazione Sanità Futura, W.G. Quality of Hospital Care and Clinical Outcomes: A Comparison between the Lombardy Region and the Italian National Data. Ann. Ig. 2024, 36, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, C.; De Ponti, E.; Mastrangelo, M.; Pennisi, F.; Cereda, D.; Corti, F.; Beretta, D.; Pelissero, G. The Contribution of the Private Healthcare Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experience of the Lombardy Region in Northern Italy. Ann. Ig. 2024, 36, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennisi, F.; Minerva, M.; Valle, Z.D.; Odone, A.; Signorelli, C. Genesis and Prospects of the Shortage of Specialist Physicians in Italy and Indicators of the 39 Schools of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine. Acta Biomed. 2023, 94, e2023096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, D.; Pennisi, F.; Pinto, A.; De Ponti, E.; Ricciardi, G.E.; Signorelli, C.; Veronese, N.; Castagna, A.; Maggi, S.; Cadeddu, C.; et al. Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Food Security among Older People: A Systematic Review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Progress on Ambient Water Quality (SDG Target 6.3). Available online: https://sdg6data.org/en/indicator/6.3.2 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- The Global Goals Goal 3: Good Health and Well-Being. Available online: https://globalgoals.org/goals/3-good-health-and-well-being/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Indexes | Variables |

|---|---|

| Demography | Fertility rate, total (births per woman) Population aged 65 and above (% of total population) Population density (people per sq. km of land area) Population growth (annual %) Population, total Urban population (% of total population) |

| Economy | GDP growth (annual %) GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) GDP, PPP (current international $) Gini index Unemployment, total (% of total labour force) (modelled ILO estimate) |

| Governance | Control of corruption Government effectiveness Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism Regulatory quality Rule of law Voice and accountability |

| Health system | Current health expenditure (% of GDP) Current health expenditure per capita, PPP (current international $) Life expectancy at birth, total (years) |

| Water Category | Causes | Arsenic and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Lead and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Mercury and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Nickel and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater | All causes | 0.203 (0.232); 0.676 | 0.268 (0.241); 0.676 | −0.224 (0.276); 0.676 | −0.278 (0.368); 0.676 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.301 (0.225); 0.676 | 0.344 (0.235); 0.676 | −0.186 (0.274); 0.676 | −0.291 (0.368); 0.676 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.118 (0.221); 0.757 | 0.142 (0.209); 0.676 | 0.024 (0.215); 0.911 | 0.600 (0.279); 0.374 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.474 (0.206); 0.374 | 0.715 (0.170); 0.016 | 0.106 (0.277); 0.848 | 0.081 (0.369); 0.875 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.194 (0.236); 0.676 | 0.053 (0.254); 0.875 | 0.251 (0.223); 0.676 | 0.327 (0.371); 0.676 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.312 (0.214); 0.676 | 0.163 (0.237); 0.676 | −0.303 (0.263); 0.676 | −0.112 (0.358); 0.866 | |

| River Water | All causes | 0.783 (0.192); 0.009 | 0.514 (0.202); 0.079 | −0.184 (0.237); 0.554 | 0.152 (0.220); 0.554 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.721 (0.202); 0.017 | 0.506 (0.200); 0.079 | −0.162 (0.233); 0.554 | 0.234 (0.214); 0.509 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | −0.194 (0.251); 0.554 | −0.276 (0.217); 0.436 | −0.161 (0.217); 0.554 | 0.141 (0.213); 0.554 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.604 (0.247); 0.079 | 0.501 (0.208); 0.079 | −0.095 (0.242); 0.700 | 0.458 (0.201); 0.093 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.444 (0.272); 0.290 | −0.333 (0.230); 0.358 | 0.198 (0.200); 0.537 | −0.157 (0.228); 0.554 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.878 (0.186); 0.004 | 0.533 (0.201); 0.079 | −0.152 (0.237); 0.554 | 0.234 (0.218); 0.509 |

| Water Category | Causes | Arsenic and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Lead and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Mercury and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Nickel and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater | All causes | 0.211 (0.190); 0.528 | 0.223 (0.224); 0.528 | −0.267 (0.189); 0.514 | −0.195 (0.277); 0.652 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.288 (0.181); 0.507 | 0.288 (0.217); 0.525 | −0.277 (0.185); 0.511 | −0.213 (0.271); 0.652 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.061 (0.183); 0.809 | 0.120 (0.215); 0.698 | 0.210 (0.181); 0.528 | 0.597 (0.231); 0.135 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.454 (0.170); 0.135 | 0.704 (0.174); 0.013 | −0.129 (0.196); 0.652 | −0.023 (0.280); 0.935 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.199 (0.199); 0.528 | 0.100 (0.239); 0.776 | 0.379 (0.190); 0.350 | 0.292 (0.286); 0.528 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.316 (0.185); 0.489 | 0.157 (0.229); 0.652 | −0.219 (0.194); 0.528 | −0.080 (0.283); 0.813 | |

| River Water | All causes | 0.648 (0.194); 0.036 | 0.103 (0.198); 0.730 | −0.184 (0.195); 0.709 | 0.192 (0.195); 0.709 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.592 (0.198); 0.053 | 0.093 (0.195); 0.730 | −0.153 (0.192); 0.714 | 0.263 (0.188); 0.590 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | −0.094 (0.224); 0.739 | −0.038 (0.188); 0.879 | −0.139 (0.185); 0.714 | 0.100 (0.187); 0.730 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.529 (0.211); 0.119 | 0.133 (0.198); 0.714 | −0.141 (0.197); 0.714 | 0.428 (0.178); 0.119 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.432 (0.232); 0.302 | 0.008 (0.208); 0.970 | 0.129 (0.206); 0.714 | −0.214 (0.203); 0.709 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.768 (0.177); 0.006 | 0.144 (0.199); 0.714 | −0.199 (0.196); 0.709 | 0.258 (0.194); 0.590 |

| Model Number | Causes | Arsenic and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Lead and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Mercury and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Nickel and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | All causes | 0.017 (0.140); 0.951 | 0.059 (0.147); 0.924 | −0.221 (0.153); 0.539 | 0.096 (0.221); 0.924 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.126 (0.144); 0.635 | 0.145 (0.150); 0.597 | −0.184 (0.164); 0.563 | 0.073 (0.232); 0.951 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.233 (0.198); 0.563 | 0.255 (0.191); 0.539 | 0.024 (0.208); 0.951 | 0.475 (0.280); 0.530 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.346 (0.170); 0.467 | 0.593 (0.134); 0.012 | 0.108 (0.218); 0.924 | 0.388 (0.291); 0.539 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.032 (0.178); 0.951 | 0.254 (0.179); 0.539 | 0.249 (0.145); 0.530 | 0.012 (0.287); 0.969 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.147 (0.139); 0.563 | −0.038 (0.149); 0.951 | −0.301 (0.139); 0.467 | 0.250 (0.217); 0.563 | |

| Model 3 | All causes | 0.018 (0.109); 0.969 | 0.094 (0.108); 0.686 | −0.137 (0.115); 0.527 | −0.134 (0.176); 0.686 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.127 (0.128); 0.627 | 0.174 (0.127); 0.516 | −0.116 (0.148); 0.686 | −0.114 (0.216); 0.841 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.232 (0.200); 0.527 | 0.246 (0.196); 0.527 | −0.023 (0.212); 0.969 | 0.628 (0.288); 0.376 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.346 (0.175); 0.401 | 0.593 (0.139); 0.019 | 0.115 (0.232); 0.841 | 0.476 (0.316); 0.516 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.032 (0.184); 0.969 | 0.255 (0.185); 0.516 | 0.274 (0.151); 0.402 | 0.020 (0.319); 0.969 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.149 (0.085); 0.402 | 0.003 (0.086); 0.969 | −0.207 (0.076); 0.221 | −0.012 (0.139); 0.969 | |

| Model 4 | All causes | 0.005 (0.115); 0.980 | 0.085 (0.118); 0.777 | −0.219 (0.139); 0.432 | −0.123 (0.184); 0.777 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.105 (0.135); 0.777 | 0.153 (0.138); 0.628 | −0.243 (0.175); 0.460 | −0.083 (0.223); 0.954 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.287 (0.205); 0.460 | 0.333 (0.200); 0.411 | 0.036 (0.266); 0.976 | 0.597 (0.301); 0.411 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.325 (0.185); 0.411 | 0.599 (0.152); 0.041 | 0.007 (0.288); 0.980 | 0.545 (0.316); 0.411 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.120 (0.171); 0.777 | 0.161 (0.185); 0.777 | 0.046 (0.148); 0.962 | 0.127 (0.295); 0.953 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.169 (0.088); 0.411 | 0.021 (0.093); 0.976 | −0.249 (0.094); 0.267 | −0.027 (0.145); 0.976 |

| Model Number | Causes | Arsenic and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Lead and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Mercury and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value | Nickel and Its Compounds β (SE); p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | All causes | 0.352 (0.149); 0.245 | 0.154 (0.132); 0.581 | −0.122 (0.123); 0.581 | 0.041 (0.117); 0.845 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.300 (0.172); 0.581 | 0.167 (0.142); 0.581 | −0.102 (0.133); 0.680 | 0.130 (0.123); 0.581 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.139 (0.277); 0.829 | −0.065 (0.222); 0.845 | −0.196 (0.191); 0.581 | 0.209 (0.185); 0.581 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.197 (0.252); 0.680 | 0.228 (0.190); 0.581 | −0.041 (0.173); 0.849 | 0.373 (0.146); 0.235 | |

| Mental disorders | 0.079 (0.251); 0.845 | −0.001 (0.196); 0.998 | 0.150 (0.128); 0.581 | −0.063 (0.168); 0.845 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.492 (0.159); 0.160 | 0.195 (0.145); 0.581 | −0.092 (0.136); 0.722 | 0.129 (0.128); 0.581 | |

| Model 3 | All causes | 0.192 (0.161); 0.575 | 0.106 (0.116); 0.575 | −0.150 (0.104); 0.575 | −0.021 (0.104); 0.921 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.191 (0.199); 0.575 | 0.132 (0.138); 0.575 | −0.122 (0.128); 0.575 | 0.089 (0.122); 0.671 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.392 (0.308); 0.575 | −0.029 (0.225); 0.937 | −0.183 (0.196); 0.575 | 0.265 (0.186); 0.575 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.269 (0.300); 0.575 | 0.234 (0.198); 0.575 | −0.042 (0.179); 0.921 | 0.392 (0.152); 0.471 | |

| Mental disorders | 0.114 (0.301); 0.871 | 0.001 (0.204); 0.994 | 0.143 (0.131); 0.575 | −0.063 (0.178); 0.871 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.285 (0.162); 0.575 | 0.129 (0.114); 0.575 | −0.129 (0.102); 0.575 | 0.049 (0.102); 0.856 | |

| Model 4 | All causes | 0.208 (0.168); 0.645 | 0.106 (0.120); 0.662 | −0.231 (0.123); 0.645 | −0.019 (0.108); 0.950 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.199 (0.210); 0.662 | 0.132 (0.143); 0.662 | −0.232 (0.150); 0.645 | 0.089 (0.127); 0.662 | |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 0.395 (0.324); 0.645 | −0.030 (0.232); 0.950 | −0.169 (0.243); 0.662 | 0.265 (0.192); 0.645 | |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 0.270 (0.316); 0.662 | 0.233 (0.204); 0.645 | −0.173 (0.213); 0.662 | 0.393 (0.158); 0.572 | |

| Mental disorders | −0.029 (0.254); 0.950 | −0.008 (0.168); 0.964 | −0.056 (0.131); 0.807 | −0.109 (0.145); 0.662 | |

| Neoplasms | 0.330 (0.160); 0.645 | 0.131 (0.114); 0.645 | −0.150 (0.126); 0.645 | (0.103); 0.724 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pinto, A.; Minutolo, G.; Pennisi, F.; Stacchini, L.; De Ponti, E.; Ricciardi, G.E.; Nucci, D.; Signorelli, C.; Baldo, V.; Gianfredi, V. Water Quality, Environmental Contaminants and Disease Burden in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Associations with Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Environments 2026, 13, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010036

Pinto A, Minutolo G, Pennisi F, Stacchini L, De Ponti E, Ricciardi GE, Nucci D, Signorelli C, Baldo V, Gianfredi V. Water Quality, Environmental Contaminants and Disease Burden in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Associations with Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Environments. 2026; 13(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010036

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Antonio, Giuseppa Minutolo, Flavia Pennisi, Lorenzo Stacchini, Emanuele De Ponti, Giovanni Emanuele Ricciardi, Daniele Nucci, Carlo Signorelli, Vincenzo Baldo, and Vincenza Gianfredi. 2026. "Water Quality, Environmental Contaminants and Disease Burden in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Associations with Disability-Adjusted Life Years" Environments 13, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010036

APA StylePinto, A., Minutolo, G., Pennisi, F., Stacchini, L., De Ponti, E., Ricciardi, G. E., Nucci, D., Signorelli, C., Baldo, V., & Gianfredi, V. (2026). Water Quality, Environmental Contaminants and Disease Burden in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Associations with Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Environments, 13(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010036