The Synergy Between the Travel Cost Method and Other Valuation Techniques for Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- How has the integration of TCM with other valuation methods evolved geographically and temporally?

- ii.

- Which method combinations are most frequently applied and in which ecosystem types?

- iii.

- Which method combinations are most frequently applied and in which cultural ecosystem services

- iv.

- How do monetary estimates vary across methods and ecosystems?

- v.

- What are the main advantages and limitations of methodological integration?

2. Theoretical Framework

Environmental Economic Valuation Methods

| Valuation Method | Type Method | Core Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Methods of revealed preferences | Travel Cost | The TCM estimates recreational value of natural sites by analyzing the actual travel expenses incurred by visitors [31]. The Individual TCM, its most common variant, uses survey data on trip costs, visitation frequency, and socioeconomic characteristics to generate realistic use value estimates, supporting decisions on access fees, site management, and investment planning [22]. |

| Hedonic Pricing | The HPM estimates the value of environmental attributes by measuring how they influence the prices of market goods, such as housing [25,32]. It assumes that market prices embed multiple characteristics, including environmental factors like air quality and proximity to natural areas [25,32]. | |

| Avoided Cost | The ACM is used to estimate the costs incurred to avoid or reduce undesired negative effects [24]. The necessary condition is that ecosystem services directly influence economic agents and that the application of strategies to avoid or reduce undesired impacts is feasible [33]. | |

| Replacement Cost | The RCM estimates the monetary value of ecosystem services by calculating the cost of replacing lost ecological functions with artificial alternatives [34]. It does not rely on surveys but instead uses technical and economic data on feasible substitutes, making it suitable for valuing services like water regulation, erosion control, and air purification [35]. | |

| Methods of declared preferences | Contingent Valuation | The CVM estimates individuals’ willingness to pay for environmental goods that lack market prices by presenting hypothetical scenarios through surveys. It captures both use and non-use values, making it especially useful in protected areas and settings where communities depend heavily on natural resources [25,35]. |

| Choice Experiment | The CEM uses structured choice scenarios to estimate the marginal willingness to pay for specific ecosystem attributes, allowing values to be decomposed into environmental, cultural, and recreational components [33]. By inferring preferences from repeated choices, it provides detailed insights into attribute-specific trade-offs and effectively captures non-tangible benefits in complex, multi-service ecosystems [35,36,37]. | |

| Value Market Method | Market Price | The MPM values ecosystem goods and services traded in formal markets by combining quantities with prevailing prices, assuming these reflect consumers’ willingness to pay [38,39]. Widely applied in wetlands and lakes across diverse activities, MPM provides realistic economic values that support environmental management and policy decisions [38,40]. |

| Benefit Transfer technique | Benefit Transfer | The BTM estimates ecosystem service values in areas lacking primary data by transferring results from previously studied sites [41,42], making it a cost-effective and time-efficient tool for policy and environmental management [43]. It can be applied through value transfer, function transfer, or meta-analytic approaches that account for contextual differences to improve accuracy [25,41]. |

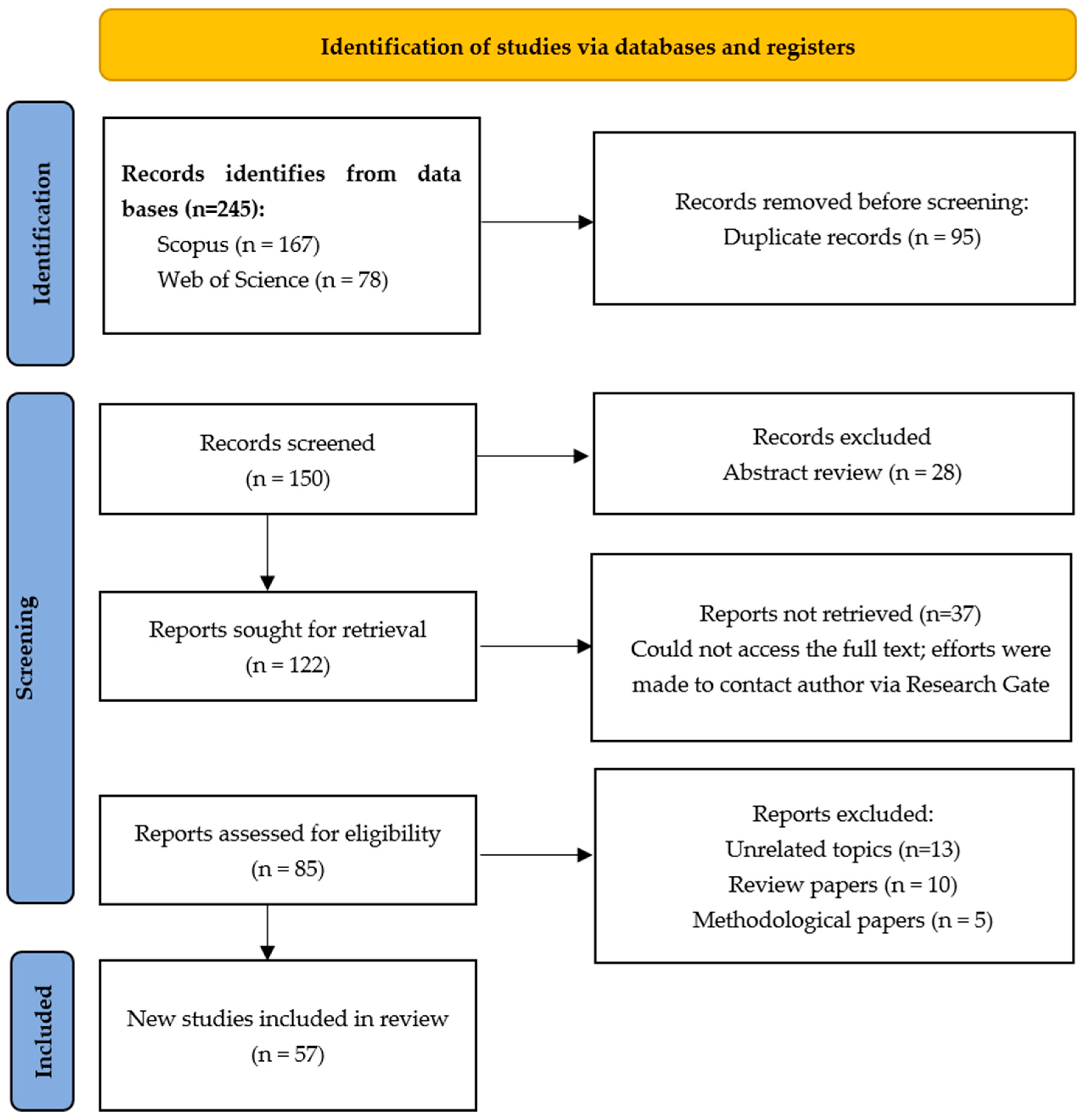

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Systematic Review Protocols

3.2. Literature Search Protocol

3.3. Data Extraction Protocol

3.4. Quality Assessment

3.5. Ecosystems Classification

- -

- Marine-coastal. This category encompasses ecosystems associated with the open sea, coastline, beaches, mangroves, estuaries, coastal lagoons, reefs, and other related environments.

- -

- Natural continental waters. This category encompasses rivers, lakes, and wetlands, among other water bodies.

- -

- Artificial continental waters/infrastructure. This category encompasses reservoirs, dams, urban lakes, and other water-related infrastructure.

- -

- Forest land and recreation. This classification encompassed forests of all types, mountains, and other related ecosystems.

- -

- Agriculture/plantations. The category in question encompasses rice paddies, forest plantations, oil palm plantations, and other related ecosystems.

- -

- Urban-cultural. The category in question encompassed a wide array of urban green spaces, including urban parks, green infrastructure, city parks, green areas in cities, museums, cultural institutions, mosques, sporting events, and other related ecosystems.

4. Results

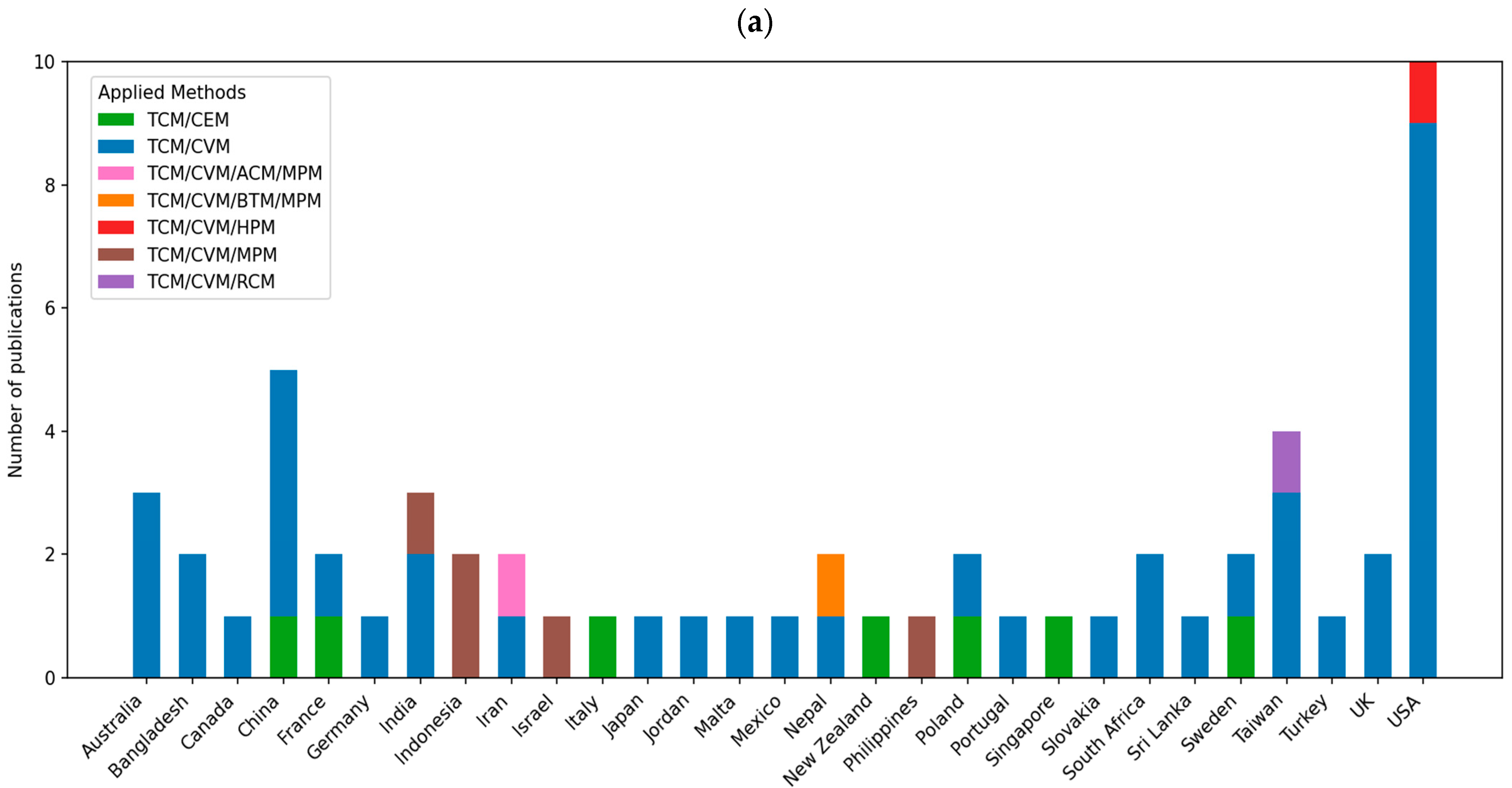

4.1. Geographic Distribution of Studies According to the Combined Methods Applied

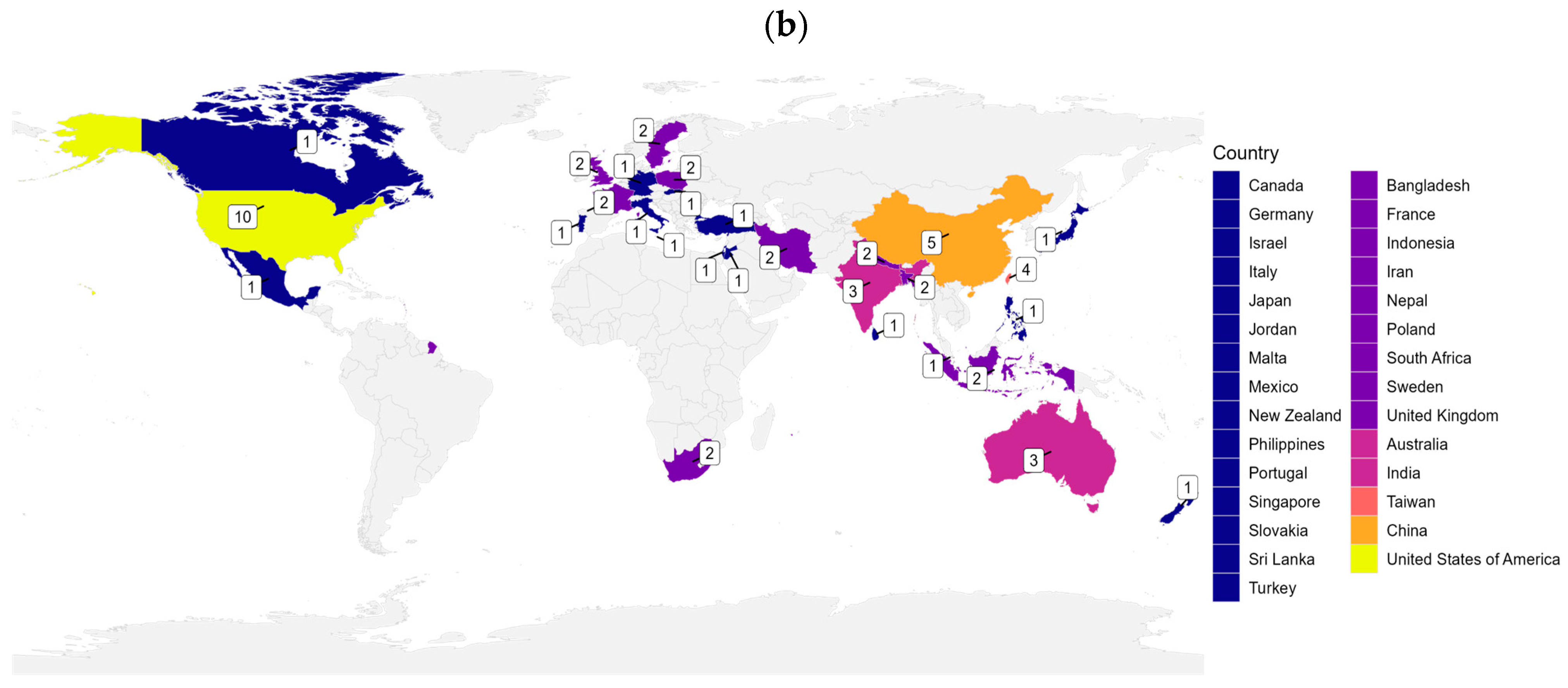

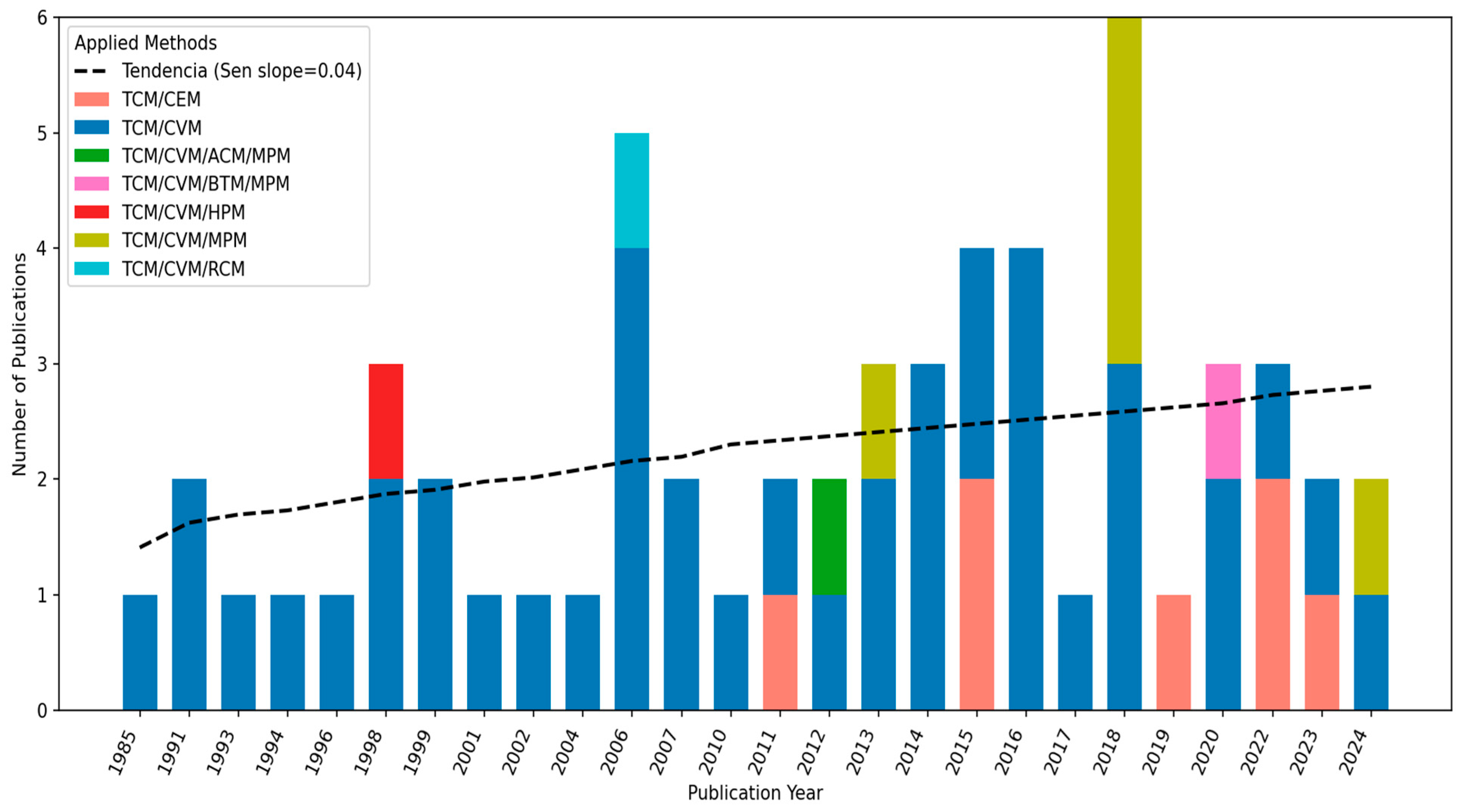

4.2. Evolution of Countries That Applied the Travel Cost Method Alongside Other Valuation Methods over the Years

4.3. The Evolution of Studies That Applied the Travel Cost Method Alongside Other Valuation Methods over the Years

4.4. Cultural Ecosystem Services According to Combined Applied Economic Valuation Methods

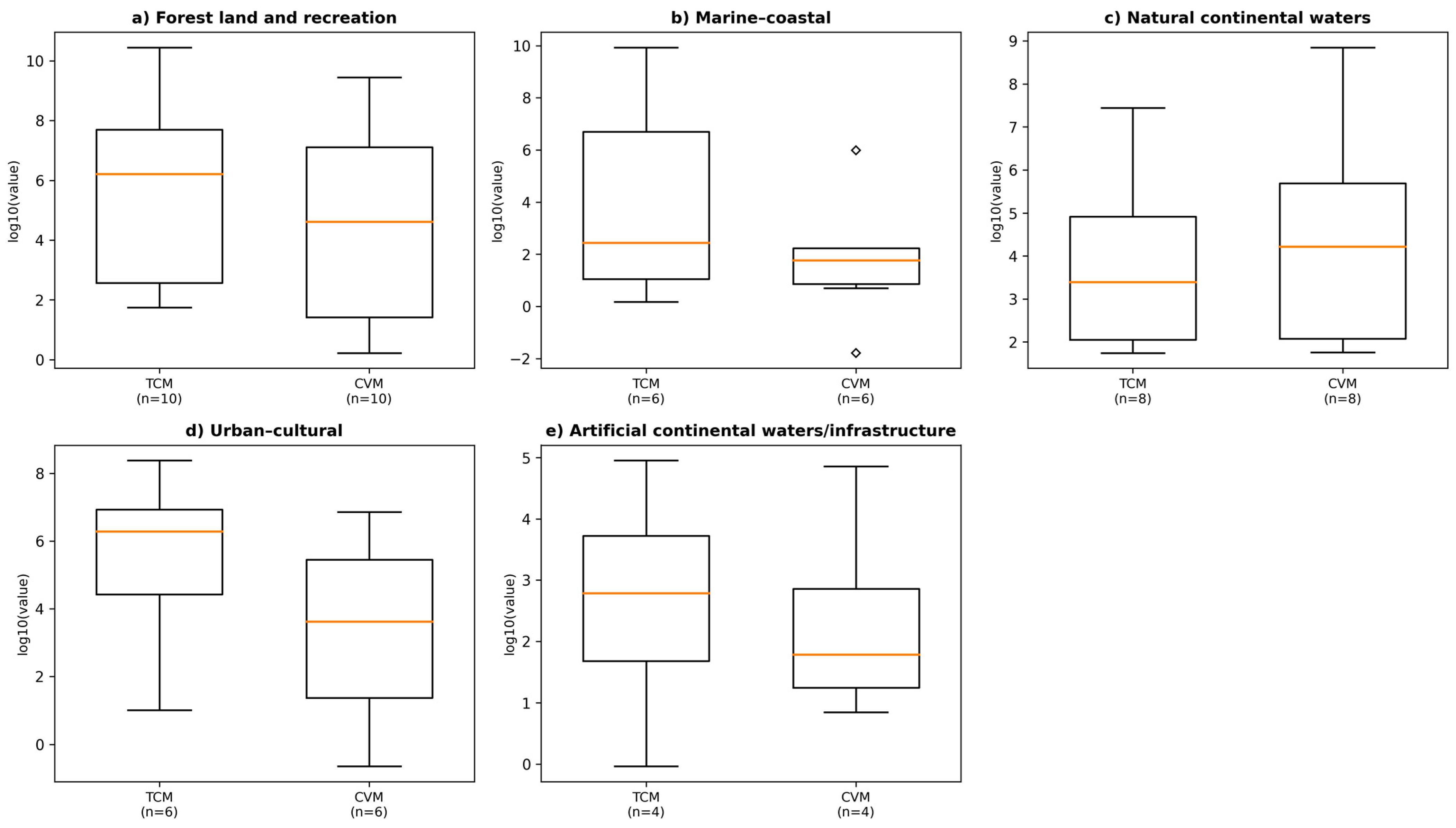

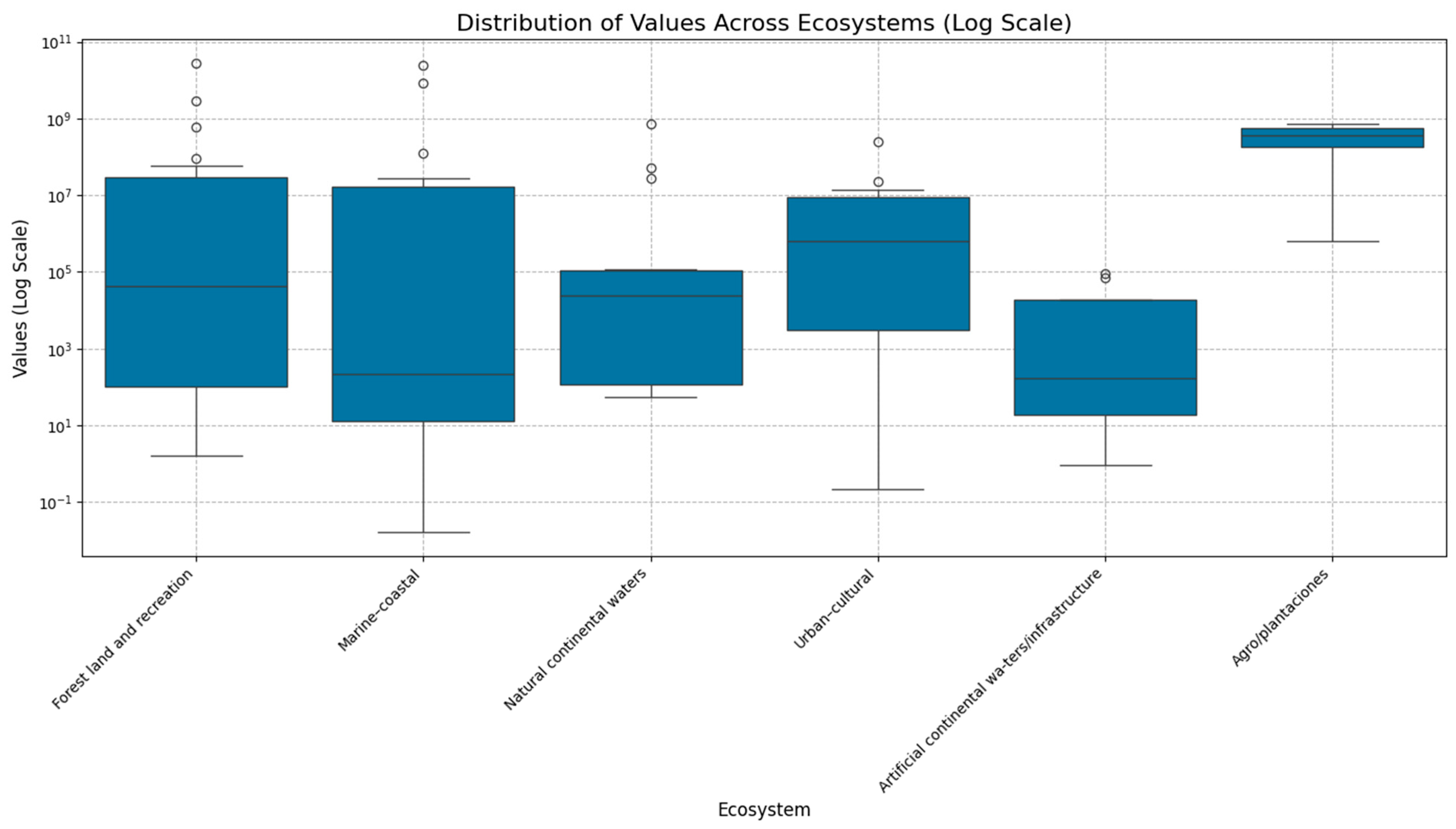

4.5. Statistical Comparisons of Monetary Results According to Ecosystems

Monetary Valuation Results by Ecosystem Type and Valuation Method

5. Discussion

5.1. Geographic Distribution and Trends

5.2. Comparisons of Monetary Results According to Methods and Ecosystems

5.3. Methodological Quality and Limitations

5.4. Limitations of This Review

5.5. Policy Implications and Standardization Needs

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meinard, Y. Rationalizing environmental decision-making through economic valuation? Humanistyka I Przyrodozn. 2021, 25, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapa-Tankosić, J. Techniques of economic valuation of environmental goods. Int. J. Econ. Pract. Policy 2022, 19, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, S.; Kenter, J.O. Economic valuation of wildlife conservation. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, S. The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Pérez, J.A.; Cázares-Moran, M.A.; Avitia-Deras, A.; Loria-Tzab, C.; Tamay-Jiménez, R.A. Valoración económica como estrategia de recuperación de espacios naturales. Estudio de caso “La Aguada En Francisco J. Mujica, México”/Economic valuation as a strategy for the recovery of natural areas. Case study “La Aguada In Francisco J. Mujica, México.”. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2022, 5, 1400–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellet-Viciano, L.; Hernández-Chover, V.; Hernández-Sancho, F. The economic and environmental impact of fire preventive strategies in the Mediterranean region. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. Global Indicator Framework After 2022 Refinement. 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework%20after%202022%20refinement_Eng.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Aznar, J.; Guijarro, F. Nuevos Métodos de Valoración: Modelos Multicriterio, 2nd ed.; Editorial Universidad Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2012; ISBN 978-84-8363-982-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. Economic Valuation and the Narutal World; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 1-59726-040-1.

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.1. Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Ed.) Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. In The Millennium Eco-System Assessment Series; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- TEEB (Ed.) The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations of TEEB. In The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.2 Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure. 2023. Available online: https://cices.eu/content/uploads/sites/8/2023/08/CICES_V5.2_Guidance_24072023.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Booi, S.; Mishi, S.; Andersen, O. Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review of Provisioning and Cultural Ecosystem Services in Estuaries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, E.; Lucchitta, B.; Penati, T. Valuing ecosystem services at the urban level: A critical review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P. Evaluation of cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Economic Study of the Monetary Evaluation of Recreation in National Parks; U. S. Department of Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 1949.

- Kerkhof, A.; Drissen, E.; Uiterkamp, A.S.; Moll, H. Valuation of environmental public goods and services at different spatial scales: A review. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2010, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolander, C.; Lundmark, R. A Review of Forest Ecosystem Services and Their Spatial Value Characteristics. Forests 2024, 15, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.A.; Jupe, L.L.; Aguiar, F.C.; Collins, A.M.; Davidson, S.J.; Freeman, W.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Lobato-de Magalhães, T.; McKinley, E.; Nuno, A.; et al. A global systematic review of the cultural ecosystem services provided by wetlands. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 70, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáñez-Cota, L.A.; Borbón-Morales, C.G.; Laborín-Álvarez, J.F.; González-Ocampo, H.A.; Rueda-Puente, E.O. Systematic review of the travel cost method: An approach to the economic valuation of natural protected areas. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst 2023, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, J.; Dyack, B. Testing for convergent validity between travel cost and contingent valuation estimates of recreation values in the Coorong, Australia. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2010, 54, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrecht, J. Use value of cultural experiences: A comparison of contingent valuation and travel cost. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAM. Guía de Valoración Económica del Patrimonio Natural; Ministerio del Ambiente: Lima, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R.T.; Hanemann, W.M. Chapter 17 Contingent Valuation. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Mler, K.-G., Vincent, J.R., Eds.; Valuing Environmental Changes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 821–936. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J. A Comparison of the Effect of Multiple Destination Trips on Recreation Benefits as Estimated by Travel Cost and Contingent Valuation Methods. J. Leis. Res. 2006, 38, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Chien, Y.-L.; Lin, Y.-M. Alternative approach to combining revealed and stated preference data: Evaluating water quality of a river system in Taipei. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 1998, 2, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirnejad, H.; Jahanifar, K. Comparison of Contingent Valuation and Travel Cost Method in Estimating the Recreational Values of a Forest Park in Iran. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2018, 21, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Lozano, J.L.; López-Upton, J.; Jesús Vargas-Hernández, J.; Ávila-Angulo, M.L. Economic valuation of the forest biodiversity in Mexico, a review. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Y Del Ambiente 2017, 23, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azqueta, D.; Alviar, M.; Domínguez, L.; O´ryan, R. Introducción a la Economía Ambiental; SIDALC: Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, A.; Pérez, L.P.Y.; Sanjuán, A.I.; Hurlé, J.B. Análisis hedónico de los precios de la tierra en la provincia de Zaragoza. Rev. Española De Estud. Agrosociales Y Pesq. 2004, 202, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; He, X. Application of Choice Experiment and Individual Travel Cost Methods in Recreational Value Evaluation. Wetlands 2022, 42, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Recent Developments; OECD: Paris, France, 2006; ISBN 978-92-64-01004-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gaterell, M.R.; Morse, G.K.; Lester, J.N. A Valuation of Rutland Water using Environmental Economics. Environ. Technol. 1995, 16, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Bravi, M.; Caprioli, C.; Dell’Anna, F. Combining Revealed and Stated Preferences to design a new urban park in a metropolitan area of North-Western Italy. Ecol. Model. 2023, 483, 110436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldt, T.; Mortazavi, R. Estimating and comparing demand for a music event using stated choice and actual visitor behaviour data. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, K.B.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, G. Economic valuation of wetland products and services: A case study of Sone Beel, India. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2024, 15, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Valuing Ecosystem Services as Productive Inputs. Econ. Policy 2007, 22, 177+179–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, A.; Job, E.; Thomas, A. Willingness to Pay to Conserve Wetland Ecosystems: A Case Study of Vellayani Fresh Water Lake in South India. Agriculture 2015, 5, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, J.; Johnston, R.J.; Roseberger, R.S.; Brouwer, R. Introduction: Benefit Transfer of Environmental and Resource Values. In Benefit Transfer of Environmental and Resource Values; The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 14, pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-94-017-9929-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.A.; Hoehn, J.P. Valuing environmental goods and services using benefit transfer: The state-of-the art and science. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, K.J.; Bergstrom, J.C. Benefit transfer studies: Myths, pragmatism, and idealism. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETC/ULS. Updated CLC Illustrated Nomenclature Guidelines; ETC/ULS: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- RAMSAR. Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands; RAMSAR: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. Habitat Classification Scheme. 2012. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/habitat-classification-scheme (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Dong, S.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F. Rural landscape types and recreational value spatial analysis of valley area of Loess Plateau: A case of Hulu Watershed, Gansu Province, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, B.; Huang, L.; Li, A.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; et al. Novel method of ecological damage assessment for intentional destruction of cultural relics and historic sites. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2398689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Tsai, M.H.; Lin, W.T.; Ho, Y.F.; Tan, C.H. Multifunctionality of paddy fields in Taiwan. Paddy Water Environ. 2006, 4, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L.; Chuang, C.-T.; Jan, R.-Q.; Liu, L.-C.; Jan, M.-S. Recreational Benefits of Ecosystem Services on and around Artificial Reefs: A Case Study in Penghu, Taiwan. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 85, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Wang, C.-H. Estimating the Total Economic Value of Cultivated Flower Land in Taiwan. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4764–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, P.; Tewari, V.P. A comparison between TCM and CVM in assessing the recreational use value of urban forestry. Int. For. Rev. 2006, 8, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, G. Estimation of Commmunity Values of Lakes: A Study of Lake Mokoan in Victoria, Australia. Econ. Anal. Policy 1999, 29, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, G.; Kennedy, J. Estimating the Economic Value of Mount Buffalo National Park with the Travel Cost and Contingent Valuation Models. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, C.; Heyes, A. Willingness to Pay Versus Willingness to Travel: Assessing the Recreational Benefits from Dartmoor National Park. J Agric. Econ. 1999, 50, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voke, M.; Fairley, I.; Willis, M.; Masters, I. Economic evaluation of the recreational value of the coastal environment in a marine renewables deployment area. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 78, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.Z.; Hossain, T.; Siddiqui, O.I.; Islam, M.S. Economic valuation of the tourist spots in Bangladesh. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2018, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.K.; Farjana, F. Economic potentials of the aesthetic world heritage sites in the south-west region of Bangladesh. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2020, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.; Ahmadian, M.; KhaliliAraghi, M.; Rahbar, F. Estimating Total Economic Value of Coral Reefs of Kish Island (Persian Gulf). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, B.M.; Farolfi, S.; Hassan, R.M. Estimating water demand for domestic use in rural South Africa in the absence of price information. Water Policy 2007, 9, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikgang, J.; Hosking, S. A comparison of the values of water inflows into selected South African estuaries: The Heuningnes, Kleinmond, Klein, Palmiet, Cefane, Kwelera and Haga-Haga. Water Resour. Econ. 2016, 16, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Wang, L.; Koirala, A.; Shrestha, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Aye, W.N. Valuation of Ecosystem Services from an Important Wetland of Nepal: A Study from Begnas Watershed System. Wetlands 2020, 40, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, P.; Atreya, K.; Pant, K.P.; Kumar, L. Tourism and wetland conservation: Application of travel cost and willingness to pay an entry fee at Ghodaghodi Lake Complex, Nepal. Nat. Resour. Forum 2016, 40, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Comparan, J.C.; Fischer, D.W. Economic Valuation of the Benefits of Recreational Fisheries in Manzanillo, Colima, Mexico. Tour. Econ. 2001, 7, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carandang, A.P.; Camacho, L.D.; Gevaña, D.T.; Dizon, J.T.; Camacho, S.C.; de Luna, C.C.; Pulhin, F.B.; Combalicer, E.A.; Paras, F.D.; Peras, R.J.J.; et al. Economic valuation for sustainable mangrove ecosystems management in Bohol and Palawan, Philippines. For. Sci. Technol. 2013, 9, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://data.imf.org/en (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Seller, C.; Stoll, J.R.; Chavas, J.-P. Validation of empirical measures of welfare change: A comparison of nonmarket techniques. Land Econ. 1985, 61, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.D.; Walsh, R.G.; McKean, J.R. Comparable estimates of the recreational value of rivers. Water Resour. Res. 1991, 27, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.; McTernan, J. Economic Value of Instream Flow for Non-Commercial Whitewater Boating Using Recreation Demand and Contingent Valuation Methods. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, F.B.; Williams, A.T.; Williams, A.T.; Coman, C.; Micallef, A.; Unal, O. A comparison of tourist evaluation of beaches in malta, romania and turkey. World Leis. J. 2002, 44, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Adamowicz, W.; Bennett, J.; Brouwer, R.; Cameron, T.A.; Hanemann, W.M.; Hanley, N.; Ryan, M.; Scarpa, R.; et al. Contemporary Guidance for Stated Preference Studies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 4, 319–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, F.; Tsinaslanidis, P. Analysis of Academic Literature on Environmental Valuation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yang, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Rao, E. Evaluating value of natural landscapes in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ni, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xia, B. Public perception and preferences of small urban green infrastructures: A case study in Guangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.C.; Groothuis, P.A.; Southwick, R.; Foster-Turley, P. Measuring the economic benefits of Saginaw Bay coastal marsh with revealed and stated preference methods. J. Great Lakes Res. 2009, 35, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, R.M.W. Economic values for recreational planning at Horton Plains National Park, Sri Lanka. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.; Creel, M.; Park, T. Comparing benefit estimates from travel cost and contingent valuation using confidence intervals for Hicksian welfare measures. Appl. Econ. 1991, 23, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, E.L.; Carline, R.; Guldin, R.W.; Cordell, H.K. Economic amenity values of wildlife: Six case studies in Pennsylvania. Environ. Manag. 1993, 17, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, P.; Loomis, J. Comparing the Economic Value of Mountain Biking Estimated Using Revealed and Stated Preference. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1998, 41, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzner, M.; Švajda, J. Preferences of tourists with regard to changes of the landscape of the Tatra National Park in Slovakia. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabe, M.; Oka, T. Benefit from improvement of organic contamination of Tokyo Bay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1996, 32, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, M.; Fehmi, M. Estimation of Recreational Use Value of Forest Resources by Using Individual Travel Cost and Contingent Valuation Methods (Kayabasi Forest Recreation Site Sample). J. Appl. Sci. 2006, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, V.; Aswath, S.; Senthikumar, S.; Malairasan, U.; Paramasivam, R. Not Too Small to Benefit Society: Economic Valuation of Urban Lake Ecosystems Services. Indian J. Agric. Econ. 2023, 78, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.; Kawa, N. Comparing Economic Values of Trout Anglers and Nontrout Anglers in Colorado’s Stocked Public Reservoirs. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2012, 32, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Dhakal, B.; Yao, R.; Barnard, T.; Maunder, C. Non-timber Values from Planted Forests: Recreation in Whakarewarewa Forest. New Zealand J. For. 2011, 55, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Walyoto, S.; Peranginangin, J. Economic Analysis of Environmental and Cultural Impacts of the Development of Palm Oil Plantation. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2018, 8, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.J.; Bilyard, G.R.; Link, S.O.; Ulibarri, C.A.; Westerdahl, H.E.; Ricci, P.F.; Seely, H.E. Valuation of Ecological Resources and Functions. Environ. Manag. 1998, 22, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ecosystems | Frequency | Valuation Method | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Std | q25 | q75 | iqr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest land and recreation | 12 | Contingent Valuation | 2.45 × 108 | 1.53 × 104 | 1.67 × 100 | 2.82 × 109 | 8.12 × 108 | 3.58 × 101 | 7.57 × 106 | 7.57 × 106 |

| Travel Cost | 2.88 × 109 | 1.24 × 107 | 5.61 × 101 | 2.80 × 1010 | 8.85 × 109 | 6.20 × 102 | 5.10 × 107 | 5.10 × 107 | ||

| Marine-coastal | 9 | Contingent Valuation | 2.69 × 109 | 1.72 × 102 | 1.64 × 10−2 | 2.42 × 1010 | 8.06 × 109 | 2.13 × 101 | 4.99 × 106 | 4.99 × 106 |

| Travel Cost | 1.46 × 109 | 2.75 × 102 | 1.51 × 100 | 8.63 × 109 | 3.51 × 109 | 5.85 × 101 | 9.26 × 107 | 9.26 × 107 | ||

| Natural continental waters | 8 | Contingent Valuation | 9.48 × 107 | 3.55 × 104 | 5.78 × 101 | 7.05 × 108 | 2.47 × 108 | 1.21 × 102 | 1.33 × 107 | 1.33 × 107 |

| Travel Cost | 3.46 × 106 | 2.17 × 104 | 5.55 × 101 | 2.74 × 107 | 9.69 × 106 | 1.15 × 102 | 8.44 × 104 | 8.42 × 104 | ||

| Urban-cultural | 8 | Contingent Valuation | 5.64 × 106 | 3.54 × 105 | 2.24 × 10−1 | 2.33 × 107 | 8.74 × 106 | 6.52 × 102 | 8.86 × 106 | 8.86 × 106 |

| Travel Cost | 4.30 × 107 | 3.30 × 106 | 1.03 × 101 | 2.42 × 108 | 9.74 × 107 | 1.57 × 105 | 8.70 × 106 | 8.54 × 106 | ||

| 4 | Choice Experiment | 1.62 × 106 | 2.86 × 101 | 3.83 × 100 | 4.87 × 106 | 2.81 × 106 | 1.62 × 101 | 2.44 × 106 | 2.44 × 106 | |

| Travel Cost | 5.54 × 101 | 5.54 × 101 | 9.14 × 100 | 1.02 × 102 | 6.54 × 101 | 3.22 × 101 | 7.85 × 101 | 4.62 × 101 | ||

| Artificial continental waters/infrastructure | 4 | Contingent Valuation | 1.80 × 104 | 8.96 × 101 | 7.03 × 100 | 7.17 × 104 | 3.58 × 104 | 1.94 × 101 | 1.81 × 104 | 1.80 × 104 |

| Travel Cost | 2.30 × 104 | 1.12 × 103 | 9.19 × 10−1 | 8.99 × 104 | 4.46 × 104 | 1.34 × 102 | 2.40 × 104 | 2.39 × 104 |

| Ecosystem Type | Management Objective | Recommended Combination | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest land and recreation | Estimate recreation benefits and WTP for management (access, conservation, services) | TCM + CVM (add HPM when the objective includes capitalization in land/property values) | TCM anchors observed use values, CVM adds WTP for policy/quality scenarios; HPM is appropriate when ecosystem amenities are reflected in market prices [78,80,88]. |

| Urban-cultural | Prioritize interventions based on attribute-level trade-offs (price, crowding, access, quality) | TCM + CEM | TCM provides behavior-based values; CEM identifies marginal WTP by attribute for operational decisions [36,37]. |

| Marine-coastal | Support coastal management combining recreation with broader welfare and, when relevant, marketed services | TCM + CVM + MPM (expand with ACM/RCM for high-stakes TEV settings) | MPM captures marketed outputs, TCM recreation demand, and CVM WTP for conservation/quality change; ACM/RCM can complement when avoided damage/replacement proxies are needed in complex TEV applications [60,66]. |

| Agriculture/plantations | Value multifunctional production landscapes where some services are credibly proxied by engineered replacements | TCM + CVM + RCM | RCM approximates services via replacement/engineering costs, while TCM/CVM capture recreation-related use and stated WTP for multifunctionality [50]. |

| Natural continental waters | Value multiple services when primary valuation is incomplete and data gaps exist | TCM + CVM + BTM + MPM | BTM fills information gaps via transfer, supported by local TCM/CVM anchors and MPM for traded outputs [63]. |

| Artificial continental waters/infrastructure | Appraise recreation and management benefits in reservoirs, dams, and urban lakes | TCM + CVM | In artificial water infrastructures, TCM captures use values from observed visits while CVM elicits WTP for management/quality improvements; examples in the evidence base include urban lake ES valuation and reservoir-based recreation contexts [84,85]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánchez Bardales, E.; García Rosero, L.M.; Arellanos Carrion, E.S.; Bravo Campos, E.; Cruz Caro, O. The Synergy Between the Travel Cost Method and Other Valuation Techniques for Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. Environments 2026, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010018

Sánchez Bardales E, García Rosero LM, Arellanos Carrion ES, Bravo Campos E, Cruz Caro O. The Synergy Between the Travel Cost Method and Other Valuation Techniques for Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. Environments. 2026; 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez Bardales, Einstein, Ligia Magali García Rosero, Erick Stevinsonn Arellanos Carrion, Einstein Bravo Campos, and Omer Cruz Caro. 2026. "The Synergy Between the Travel Cost Method and Other Valuation Techniques for Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review" Environments 13, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010018

APA StyleSánchez Bardales, E., García Rosero, L. M., Arellanos Carrion, E. S., Bravo Campos, E., & Cruz Caro, O. (2026). The Synergy Between the Travel Cost Method and Other Valuation Techniques for Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. Environments, 13(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010018