1. Introduction

Drinking water treatment plants (DWTPs) are vital for providing safe, potable water, a fundamental resource for human health and societal well-being [

1]. The quality of treated water is evaluated through key physicochemical parameters, with turbidity being the most critical, alongside total, settleable, filterable, and dissolved solids, as well as color, odor, and temperature [

2]. Monitoring and predicting variations in these parameters are essential for identifying physicochemical imbalances and implementing timely corrective measures to ensure compliance with national regulatory [

3,

4]. DWTPs transform raw water to meet these standards through processes such as coagulation–flocculation, sedimentation, and filtration [

5,

6].

Coagulation–flocculation, the initial and most critical stage, removes suspended particles by adding chemical coagulants and flocculants, such as aluminum sulfate, polyaluminum chloride (PAC), and nonionic polymers [

7,

8]. Following coagulation, flocs settle in sedimentation tanks, producing decanted water [

7]. However, optimizing coagulant dosages is complex due to the dynamic variability of raw water quality, driven by factors such as seasonal changes and extreme weather events. The conventional jar test, used to determine optimal dosages, is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and poorly suited for real-time adaptation, particularly in resource-constrained settings where financial limitations and inadequate infrastructure hinder rapid and continuous monitoring [

9].

To address these challenges, machine learning (ML) models have emerged as a transformative approach for predicting optimal coagulant dosages, enhancing efficiency, reducing chemical waste, and minimizing environmental impacts while ensuring consistent water quality [

10]. Traditional statistical or linear models often struggle with the complexity and variability of water quality data, leading to overfitting and limited generalization [

11,

12]. In contrast, advanced ML models demonstrate superior performance. For instance, deep learning models like the CNN-GRU hybrid excel in predicting dosages under high-turbidity conditions [

13], while integrated time-series models achieve high predictive accuracy (R

2 up to 0.985) for dynamic regulation [

14]. Similarly, the Graph Attention Multivariate Time Series Forecasting (GAMTF) model captures temporal and spatial relationships with an R

2 of 0.94 [

15]. Among these, the Random Forest (RF) model stands out for its robustness, high accuracy (often R

2 > 0.96), and ability to handle noisy, non-linear datasets without overfitting, outperforming models like Decision Trees and Support Vector Machines [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Additionally, RF’s interpretability enables transparent decision-making by identifying key variables influencing dosages, such as conductivity or temperature [

20,

21,

22].

This study proposes the application of a Random Forest model to predict optimal dosages of aluminum sulfate, PAC, and a nonionic polymer flocculant at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP in Arequipa, Peru, a region underrepresented in water treatment research. The novelty of this work lies in (1) the pioneering use of a practical ML model to optimize coagulant dosages and predict settled water turbidity in a resource-constrained Peruvian DWTP; (2) the development of a simplified, univariate RF model designed for operational practicality; and (3) the integration of the model into a real-time digital decision support platform that generates dynamic dosage curves. By enabling accurate, real-time dosage predictions, this approach minimizes chemical waste, reduces environmental impacts, enhances plant efficiency, and mitigates human error in decision-making, offering a scalable solution for sustainable water treatment in resource-limited settings.

Related Works

The demand for superior accuracy and operational efficiency in drinking water treatment has catalyzed the adoption of machine learning (ML) models, ranging from complex artificial neural networks (ANN) to simpler support vector machines (SVM) and the robust, intermediate Random Forest (RF) approach. These models enhance the precision of predicting optimal coagulant dosages, addressing the inefficiencies of conventional jar tests in water clarification processes [

23]. Early work by Zhang et al. [

24] compared SVM and k-nearest neighbor (KNN) methods for coagulant dosage prediction, finding that SVM-based regression provided adequate forecasting for large- and medium-sized DWTPs, while KNN was more effective for smaller plants. However, SVM is now often considered less effective for complex datasets compared to advanced ML models. Gomes et al. [

25] evaluated neural network models for predicting aluminum sulfate (AS) and polyaluminum chloride (PAC) dosages, achieving coefficients of determination (R

2) of 0.95 and 0.91, respectively, demonstrating high predictive capability. Similarly, Baouab Cherif [

26] proposed models based on raw and treated water parameters (turbidity, conductivity, pH), developing two models—one for turbidity below 45.5 NTU and another for higher values—achieving correlation coefficients above 0.8 and mean absolute errors of 5.47 g/m

3 and 5.69 g/m

3 for dosing, offering a practical alternative to jar testing.

Advanced neural network architectures have significantly improved coagulant dosage prediction. Kote and Wadkar [

27] investigated feed-forward neural networks (FFNN), radial basis function neural networks (RBFNN), generalized regression neural networks (GRNN), and cascaded feed-forward neural networks (CFNN) for chlorine and coagulant dosing in an Indian DWTP. By varying input variables, training functions, hidden nodes, epochs, and propagation factors, they found that RBFNN excelled for chlorine dosing (R

2 = 0.999), while CFNN with Bayesian regularization (network design 2-40-1) provided excellent coagulant estimates (R

2 = 0.947). Asmel et al. [

28] proposed a Radial-Based Neural Network (RBNN) for real-time prediction of aluminum sulfate dosages, effectively eliminating repetitive jar tests by anticipating effluent turbidity and pH. Hybrid models have further refined accuracy; Narges et al. [

29] applied an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) with subtractive clustering, using inputs such as water turbidity, pH, temperature, alkalinity, and electrical conductivity, achieving R

2 values of 0.85 and 0.84 and root mean square errors (RMSE) of 1.32 and 1.83 for alum and PAC doses, respectively. Tahraoui et al. [

30] compared ANN, ANFIS, SVM, and response surface methodology (RSM), noting that ANN slightly outperformed others in validation with high correlation coefficients and low statistical errors, though SVM was preferred for its simpler parameterization, and RSM was effective due to its high coefficients relative to parameter count. Wadkar et al. [

31] validated the CFNN model using Levenberg–Marquardt and Bayesian regularization algorithms, with hidden nodes ranging from 15 to 60, achieving R

2 values between 0.914 and 0.947, with optimal performance at 40 hidden nodes (R

2 = 0.945–0.947). Jayaweera and Aziz [

32,

33,

34] explored multilayer perceptron (MLP) and extreme learning machine (ELM) models, including ELM coupled with feed-forward neural networks (ELM-FFNN) and radial basis function neural networks (ELM-RBF), achieving R

2 values above 0.97, with ELM-RBF demonstrating superior generalization (R

2 = 0.9783) compared to GRNN (R

2 = 0.9737).

Ensemble and optimized models, particularly RF, have emerged as robust solutions for addressing water quality variability, making them ideal for resource-constrained environments where computational efficiency and interpretability are critical. Heddam [

35] compared extremely randomized trees (ERT), RF, and multiple linear regression (MLR) using water quality inputs (temperature, pH, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, conductivity), evaluating performance with R, mean absolute error (MAE), RMSE, and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE). The ERT model was the most robust (R

2 = 0.899, NSE = 0.790), slightly outperforming RF (R

2 = 0.851, NSE = 0.708), while MLR showed the lowest accuracy. Wang et al. [

36] demonstrated that RF models stabilized effluent turbidity predictions with residuals ranging from −0.2 to 0.1 NTU, reducing coagulant costs by 10%, while their Elman neural network (ENN) model achieved a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 2.38% for coagulant dose prediction and residuals between −1.0 and 1.0 mg/L, stabilizing target turbidity within 0.2 NTU. Achite et al. [

11] introduced a hybridized RF model with genetic algorithm optimization (GA-RF) for proactive dosing at the Sidi Yacoub wastewater treatment plant in Algeria, using inputs such as raw water production, turbidity, conductivity, and suspended materials. Evaluated with correlation coefficient (CC), sparse index (SI), Willmott’s concordance index (WI), and MAPE, the GA-RF model outperformed standalone RF (CC = 0.975, SI = 0.150, WI = 0.986, MAPE = 7.9). Sawalkar et al. [

37] compared ANN and RF across four input scenarios (Model A: turbidity; Model B: pH, alkalinity, temperature, turbidity; Model C: pH, alkalinity, temperature; Model D: alkalinity and turbidity) in India, finding that ANN models yielded lower RMSE for Models B and D, but both techniques significantly improved treatment efficiency and water quality.

The integration of RF models with real-time decision support systems further enhances their applicability in DWTPs, particularly in resource-constrained settings like developing regions. RF’s balance of high predictive accuracy, interpretability, and lower computational cost compared to deep learning methods like ANN makes it particularly suitable for operational environments with limited infrastructure. For instance, the real-time dosing predictions enabled by RF models, as demonstrated by Wang et al. [

36], facilitate rapid responses to abrupt water quality changes, reducing reliance on expensive chemicals and repetitive testing. Similarly, the GA-RF model’s proactive dosing capabilities [

11] highlight its potential for scalable, automated systems in DWTPs, aligning with the need for sustainable practices in regions with financial and infrastructural constraints.

In conclusion, the reviewed studies collectively affirm the effectiveness of ML models, from advanced ANN and hybrid systems to optimized RF and genetic algorithm approaches, for optimizing coagulant dosages in DWTPs. These models eliminate the need for costly and repetitive jar tests, enhance operational efficiency, reduce chemical waste, and ensure consistent water quality. RF, in particular, stands out as an intermediate model that balances predictive accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency, making it an ideal solution for resource-constrained environments. By enabling real-time, data-driven dosing decisions, these approaches contribute to sustainable water treatment practices and the provision of high-quality drinking water to diverse populations.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental work utilized polyaluminum chloride (PAC), aluminum sulfate, and a nonionic polymer flocculant as coagulants and flocculants for the jar test procedure. Raw water samples were collected in 2 L containers for the coagulation–flocculation process. Physicochemical parameters of the treated water were measured using specialized equipment: turbidity was quantified with an EPA TL2300 tungsten lamp turbidity meter (range: 0–4000 NTU); pH was measured using an HQ411D laboratory single-input pH/mV meter; water temperature was recorded with a digital thermometer; alkalinity was determined by titration with 0.02 N sulfuric acid (H2SO4) using methyl orange as an indicator for total alkalinity; calcium hardness was assessed by complexometric titration with 0.01 M EDTA using eriochrome black T as an indicator; and electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured using an HQ430D laboratory conductivity/TDS meter equipped with a CDC401 4-pole graphite cell. This applied study aims to determine, predict, and optimize coagulant dosages in drinking water treatment using machine learning techniques, specifically the Random Forest (RF) model.

A comprehensive dataset, derived from jar tests conducted on raw water samples at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra Drinking Water Treatment Plant in Arequipa, Peru, was compiled to train and validate the RF model for real-time coagulant dosage optimization.

2.1. Jar Test

The jar test, a critical and controlled procedure in the drinking water treatment process, is designed to empirically determine the optimal coagulant dosages required for effective water clarification under simulated operational conditions. This meticulous process enables the precise determination of dosages for polyaluminum chloride (PAC), aluminum sulfate, and a nonionic polymer flocculant, providing essential data for training predictive machine learning models, such as Random Forest (RF). The procedure commenced with the preparation of chemical stock solutions: PAC and aluminum sulfate were prepared at a 10% weight/volume (w/v) concentration and subsequently diluted to 1% working solutions, while the nonionic polymer flocculant stock solution was formulated at 0.05% w/v. Raw water samples were dispensed into 2 L jars for accurate dosing, ensuring consistent volumes for the coagulation–flocculation process.

The coagulation–flocculation sequence adhered to a standardized protocol to replicate treatment plant conditions. The process involved rapid mixing for 15 s at 300 rpm to ensure uniform coagulant dispersion, followed by a 10 min rest to facilitate initial particle aggregation. A secondary rapid mixing phase of 30 s at 300 rpm was conducted, succeeded by a 30 min slow mixing phase at 30 rpm to promote floc formation. The sequence concluded with a 30 min undisturbed settling period to enable sedimentation. During these stages, operational observations were recorded, including the time required for floc formation, the presence of surface creams, and any floc adhesion to jar walls or mixing components. Post-settling, samples were extracted from each 2 L jar to measure key physicochemical parameters, including turbidity, pH, temperature, alkalinity, and calcium hardness. These comprehensive measurements provided a robust dataset for training and validating the RF model to predict optimal coagulant dosages, enabling real-time optimization tailored to the operational needs of the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP in Arequipa, Peru.

During the jar test, the time required for floc formation was observed, along with any surface creams or floc adhesion to the jar walls or mixing components (see

Figure 1).

2.2. Random Forest Model

The Random Forest (RF) model, a robust ensemble learning technique, leverages the collective predictive strength of multiple decision trees while incorporating randomization to mitigate overfitting, a common challenge in predictive modeling. This approach constructs a series of decision trees, each trained on a distinct subset of the training data generated through bootstrapping, ensuring diversity in the model’s learning process. The final output, whether for classification or regression, is determined by aggregating the predictions of individual trees, using majority voting for classification tasks or averaging for regression tasks. This methodology enhances the model’s robustness and generalizability, making RF particularly suitable for predicting optimal coagulant dosages in drinking water treatment plants (DWTPs), especially in resource-constrained settings like the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP in Arequipa, Peru.

Mathematically, the RF ensemble is represented as a set of decision trees, , where each tree is trained on a unique bootstrap sample drawn from the original dataset. For a new sample , the RF prediction is defined as follows:

For regression:

where

represents the final prediction or classification for the new sample

using the Random Forest ensemble.

represents the prediction or classification made by the i-th decision tree in the ensemble for the new sample. Majority vote calculates the majority vote among the individual tree predictions for classification tasks, and n is the total number of decision trees in the RF ensemble. After all, you can average or combine the outputs of several trees, each trained on a separate subset of the data, because you can decrease overfitting. Model robustness and generalizability are improved with this ensemble technique, making it a popular choice for various machine learning applications.

2.3. Study Area and Data Collection

The Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra Drinking Water Treatment Plant (DWTP), strategically located in Arequipa, a city in southern Peru, operates within a geographically diverse region spanning coastal plains to the Andes Mountains. Characterized by an arid climate with low annual rainfall, the area faces significant challenges in water supply and treatment, compounded by its volcanic terrain and fertile soils that sustain extensive agricultural activity. The Chili River basin serves as the primary water source, critical for ensuring potability through treatment at the DWTP. The plant’s strategic importance is driven by high demand for drinking water, fueled by population growth, industrial operations, and agricultural activities. Raw water exhibits pronounced seasonal variability, with turbidity levels reaching 500–3600 NTU during January and February, while other months typically show lower turbidity ranging from 5 to 30 NTU. These fluctuations necessitate precise coagulant dosing to achieve potable water standards (turbidity < 2 NTU), making the DWTP an ideal case study for applying machine learning models to optimize water treatment processes in resource-constrained settings.

The dataset used to train the predictive Random Forest (RF) model was compiled from jar test records collected intermittently between 2015 and 2022, with each record comprising six individual experiments, totaling 2556 jar tests. The dataset evolved through three format versions, requiring robust preprocessing to address missing values, which were imputed using monthly averages and k-nearest neighbor (KNN) techniques on a per-month basis. Key raw water parameters included turbidity (NTU), pH, temperature (°C), electrical conductivity (µS/cm), total dissolved solids (mg/L), alkalinity (mg/L), and calcium hardness (mg/L). Based on these parameters, optimal dosages of polyaluminum chloride (mg/L), aluminum sulfate (mg/L), and a nonionic polymer flocculant were calculated to reduce turbidity to below 2 NTU. This comprehensive dataset enabled the training and validation of the RF model, facilitating real-time optimization of coagulant dosages for integration into a digital decision support platform tailored to the operational needs of the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP.

3. Results and Discussion

This study developed and evaluated the performance of a Random Forest (RF) model using a univariate approach to predict coagulant dosages, thereby optimizing the drinking water treatment process. The model was trained on a comprehensive dataset comprising 2556 historical jar test records, meticulously divided into a 70% subset for training and a 30% subset for rigorous performance validation (

Table 1).

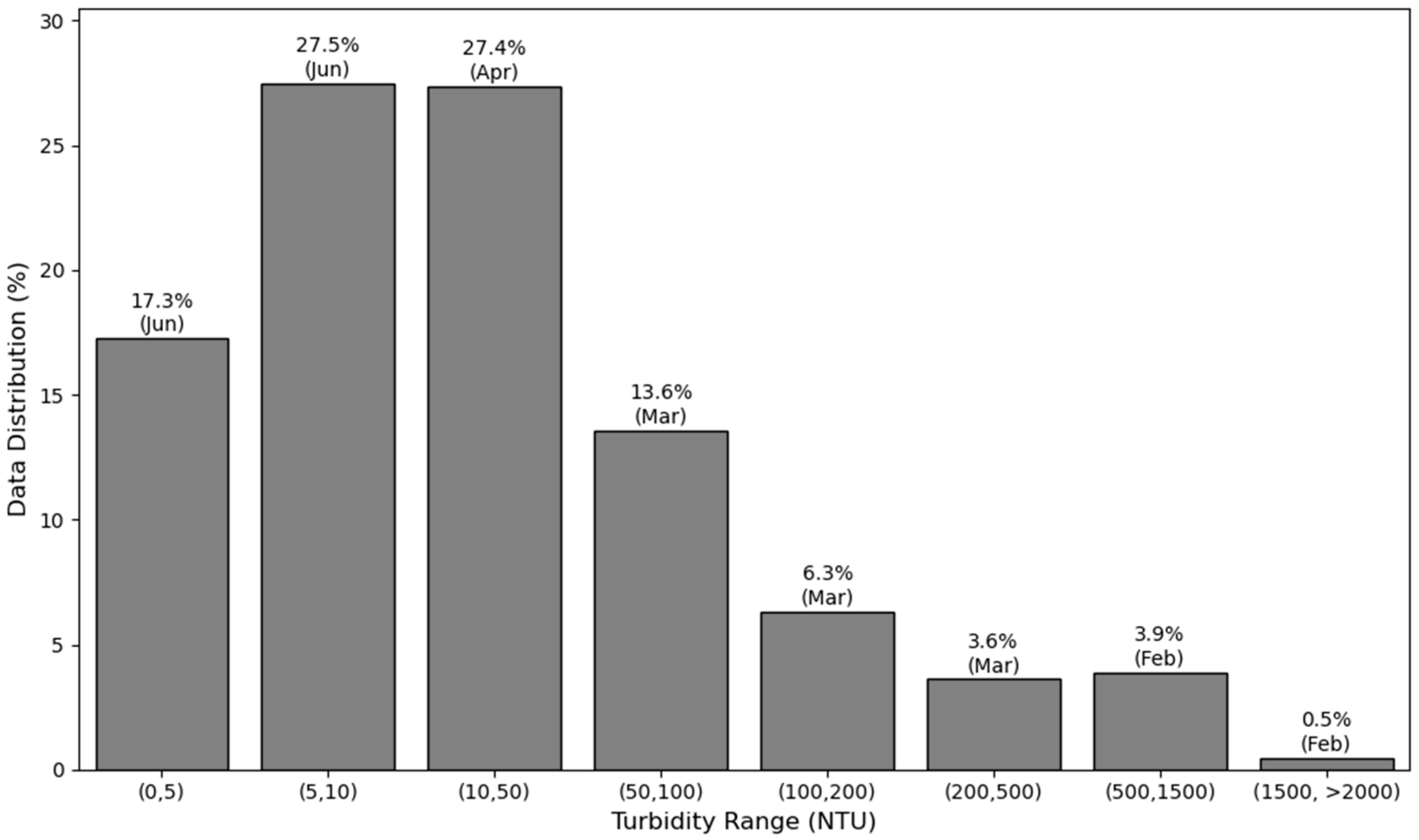

The predictive model was designed to operate reliably for raw water with turbidity levels below 150 NTU, a constraint driven by the limited availability of data in higher turbidity ranges. Data distribution analysis (

Figure 2) reveals a pronounced skew toward low turbidity, with over 50% of the data concentrated below 50 NTU. While dosing responses maintain a functional relationship up to the 150 NTU threshold, the sparsity and increased complexity of data beyond this point introduce significant bias, impairing reliable predictions for extreme turbidity events. To mitigate this bias and minimize the impact of variables on predictions, a correlation analysis and a one-way analysis of variance were conducted. Although the dosing behavior tends to follow a linear relationship for turbidity above the 50 NTU threshold, facilitating prediction up to turbidity levels of above 150 NTU.

Figure 3 shows a correlation analysis that allows us to observe the linear relationships between several predictor variables. From the results presented, which appear as a result of this graph, some trends can be identified that help to understand which variables are more relevant for the predictive model and which can be excluded due to low correlation or redundancy. First, it is observed that many of the variables are highly correlated with each other, indicating redundancies. For example, there is a very high positive correlation between SDT (mg/L), CND (us/cm), Alc_CO3 and Ca2_mg/L (R > 0.7), suggesting that the variable captures largely the same information. Large correlations between the independent variables can generate multicollinearity problems in this model, distorting the coefficients and decreasing interpretability. In this case, one of these variables should be removed in order not to lose predictive capacity and to make the model more efficient, as discussed by Maier et al. [

38]. This correlation analysis further highlights how the proper selection of variables for the predictive model makes a big difference. By eliminating redundantly Correlation analysis (

Figure 3) revealed strong linear relationships and redundancies among several predictor variables, critical for refining the input set of the Random Forest (RF) model. A high positive correlation (R > 0.7) was observed between total dissolved solids (TDS in mg/L), electrical conductivity (CND in µS/cm), alkalinity (Alc_CO3), and calcium hardness (Ca2_mg/L), indicating that these variables capture largely overlapping information about the physicochemical properties of raw water. Such high correlations can lead to multicollinearity, which distorts coefficient estimates, inflates variance, and compromises the interpretability of predictive models. To mitigate this, total dissolved solids (TDS) and calcium hardness (Ca

2+) were excluded from the final RF model input set, following the methodology recommended by Maier et al. [

38] for optimizing predictive models by eliminating redundant variables. This strategic variable selection not only enhances model efficiency but also reduces the risk of overfitting, a critical consideration for robust predictions in resource-constrained settings like the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP. The analysis underscores the importance of judicious variable selection to ensure that the RF model focuses on the most informative predictors, thereby improving predictive accuracy and operational applicability. This approach aligns with prior studies employing advanced machine learning techniques, such as artificial neural networks and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems, which emphasize the need for streamlined input sets to optimize model performance in water treatment applications [

10,

30]. Furthermore, by prioritizing variables with independent predictive power, such as turbidity (Tb_NTU) and conductivity (CND_us.cm), the model better captures the dynamic relationships influencing coagulant dosing, ensuring reliable predictions within the operational turbidity range of 0–150 NTU. This refined variable selection process supports the development of a digital decision support platform, enabling plant operators to respond efficiently to variable water quality conditions while minimizing computational demands and chemical usage.

Multiple linear regression analysis provided quantitative insights into the significance of predictor variables influencing the turbidity of decanted water, offering a foundation for optimizing the Random Forest (RF) model’s predictive accuracy. The intercept term was non-significant (

p-value = 0.82), indicating a well-centered model where turbidity variations are effectively explained by the included predictor variables rather than a baseline constant. This ensures that the model captures the dynamic relationships between water quality parameters and treatment outcomes. Analysis of individual predictors revealed critical factors for model fitting and optimization. Turbidity (Tb_NTU), representing raw water turbidity in a prior phase or measurement, exhibited a highly significant positive coefficient (0.01045,

p-value = 1.99 × 10

−54), indicating that a one-unit increase in Tb_NTU predicts an approximate 0.0104-unit increase in decanted water turbidity. This underscores the pivotal role of initial turbidity as a primary determinant in water quality prediction systems, consistent with studies employing machine learning and multivariate statistics [

10]. Temperature (Temp_C) showed a significant positive coefficient (0.0668,

p-value = 7.82 × 10

−8), suggesting that higher temperatures are associated with increased turbidity, likely due to their influence on coagulation and flocculation kinetics, as supported by recent research [

15,

39]. Conductivity (CND_us.cm) was also significant (

p-value = 4.01 × 10

−4), highlighting the role of dissolved ion levels in clarification processes, aligning with literature on the impact of physicochemical properties on water treatment outcomes [

40]. The coagulants polyaluminum chloride (PAC) and aluminum sulfate (Sulfate_Al2) demonstrated significant negative coefficients (estimates of −0.0326,

p-values of 8.39 × 10

−24 and 1.50 × 10

−24, respectively), confirming that higher dosages reduce turbidity proportionally, a critical finding for optimizing coagulation–flocculation processes in DWTPs [

41]. Similarly, the nonionic polymer exhibited a highly significant negative relationship with turbidity (

p-value = 1.45 × 10

−7), supporting its role as a flocculating agent that enhances fine particle sedimentation, as widely documented [

42]. These results collectively emphasize the importance of selecting operational and chemical dosing parameters to ensure consistent turbidity reduction in decanted water, particularly in resource-constrained settings like the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP. The RF model was developed using the R programming language with the randomForest library, enabling robust prediction of decanted water turbidity. To enhance model accuracy, total dissolved solids (TDS) and calcium hardness (Ca

2+) were excluded due to their high collinearity with other variables, which could compromise predictive performance by introducing multicollinearity. This decision, aligned with Maier et al. [

38], minimized redundancy and improved model efficiency, ensuring that the RF model focuses on the most informative predictors. By integrating these significant variables into a streamlined input set, the model supports real-time optimization of coagulant dosages, facilitating the development of a digital decision support platform tailored to the operational needs of the DWTP, as further evidenced by its ability to handle variable water quality conditions efficiently [

30].

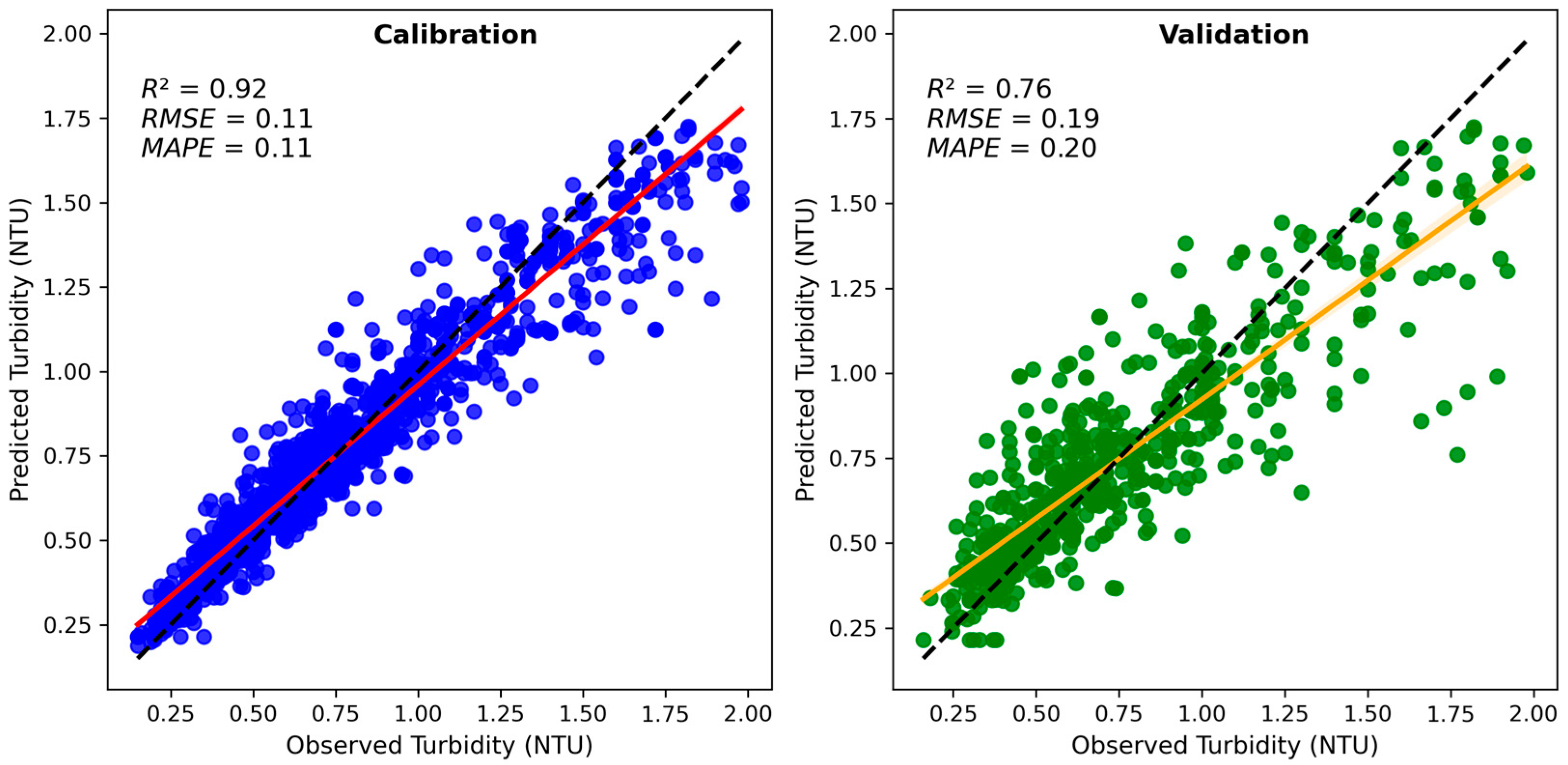

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal evolution of both observed and predicted turbidity values in the training and validation sets, providing a clear assessment of the Random Forest (RF) model’s predictive performance. In the training phase, the model closely tracks the fluctuations of observed turbidity values, demonstrating its ability to accurately capture the general trends and peaks in turbidity data, with a high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.92) that explains 92% of the data variability. The low root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.11 NTU and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 0.11 further confirm the model’s precision in the training set, indicating minimal prediction errors and robust fitting to the observed data. However, in the validation set, the model exhibits greater difficulty in predicting extreme turbidity peaks, likely due to the underrepresentation of such high-turbidity events in the training dataset, which limits the model’s ability to generalize to rare conditions. This finding underscores the critical need for a larger and more diverse dataset to enhance the model’s robustness, particularly for extreme events, as emphasized in prior turbidity prediction studies [

41]. The strategic removal of highly correlated variables, such as total dissolved solids (TDS) and calcium hardness (Ca

2+), was instrumental in mitigating multicollinearity, thereby improving the model’s overall performance and ensuring reliable predictions within the operational turbidity range of 0–150 NTU, as supported by literature on predictive modeling in water treatment processes [

15,

39]. This variable selection aligns with established methodologies for optimizing machine learning models in resource-constrained settings, such as the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP, where computational efficiency and predictive accuracy are paramount [

38]. The graphical representation in

Figure 4 provides a comprehensive view of the RF model’s strengths and limitations, highlighting its high accuracy in the training phase and identifying areas for improvement in validation, particularly for extreme turbidity events. These insights are critical for refining the model and developing a digital decision support platform that enables real-time optimization of coagulant dosages, enhancing operational efficiency in DWTPs under variable water quality conditions [

30].

The temporal evolution plot in

Figure 5, with the red line representing model predictions, demonstrates a strong alignment with observed turbidity values in the training set, confirming that the Random Forest (RF) model is not overfitted and effectively captures the underlying patterns in the data. However, in the validation set, the second plot reveals a decrease in predictive accuracy, with the coefficient of determination (R

2) dropping to 0.76, reflecting the increased complexity of unseen data. This performance decline is a common characteristic of machine learning models, where generalization to new data is challenged by variability not fully represented in the training set. Despite this reduction, the model maintains operational effectiveness, as evidenced by a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.19 NTU and a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 0.20, which remain sufficiently low for practical turbidity predictions within the target range of 0–2 NTU. These metrics indicate that, while the model’s accuracy is lower in the validation phase compared to the training set (R

2 = 0.92, RMSE = 0.11, MAPE = 0.11), it remains robust for real-world applications at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP. The observed performance gap underscores the need for a more diverse training dataset to improve generalization, particularly for extreme turbidity events, as highlighted in prior water treatment studies [

38,

41]. The validated RF model serves as the core engine of a digital decision support platform, outlined in

Figure 6, which streamlines the evaluation of various coagulant dosing scenarios by leveraging periodic jar test data. This platform enables plant operators to rapidly assess optimal dosages of polyaluminum chloride, aluminum sulfate, and nonionic polymer under varying raw water conditions, enhancing operational efficiency in resource-constrained settings. By integrating predictive analytics with real-time data, the platform facilitates proactive responses to water quality fluctuations, reducing reliance on time-intensive conventional jar tests and supporting sustainable water treatment practices [

30,

39]. This operational tool aligns with the study’s objective of optimizing coagulant dosing in DWTPs, offering a scalable solution for regions with limited resources and variable water quality.

In this study, a series of dosing curves were developed to predict the optimal application of coagulants—polyaluminum chloride (PAC) and aluminum sulfate—as a function of raw water turbidity, with each curve incorporating varying concentrations of a nonionic polymer flocculant. These curves, derived from the Random Forest (RF) model trained on jar test data, were calculated by applying a ±50% margin to the polymer doses based on the turbidity of incoming water, allowing for flexible adaptation to fluctuating water quality conditions. The resulting dosing curves (

Figure 7) provide precise data on the required dosages of both coagulants and the nonionic polymer flocculant to achieve the target turbidity of less than 2 NTU, as required for potable water standards. These curves serve as critical decision-making tools for plant operators at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP, enabling rapid and efficient responses to abrupt changes in raw water turbidity, such as those observed during seasonal peaks (2–150 NTU in January and February). By integrating predictive analytics with operational data, the dosing curves facilitate proactive management of water treatment processes, minimizing chemical overuse and operational downtime in resource-constrained settings. This approach aligns with recent advancements in predictive modeling for water treatment, which emphasize the use of data-driven tools to enhance process efficiency and [

30,

41]. The incorporation of variable polymer concentrations into the dosing curves further enhances their utility, allowing operators to tailor treatments to specific turbidity levels while optimizing resource use, a critical consideration for DWTPs in regions with limited infrastructure and high variability in water quality [

39]. The digital decision support platform, built upon these dosing curves, empowers operators to simulate and evaluate multiple dosing scenarios in real time, replacing time-intensive conventional jar tests and supporting scalable, cost-effective water treatment solutions. Tests were conducted from March to August 2023 to evaluate the model’s performance under varying raw water turbidity conditions ranging from 1 to 150 NTU. The results showed that the model accurately predicted coagulant dosages close to field values when the decanted water turbidity ranged between 0.5 and 0.6 NTU.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the efficacy of a streamlined Random Forest (RF) model, integrated into a digital decision support platform, as a transformative approach for optimizing coagulant dosages in response to significant turbidity fluctuations at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra Drinking Water Treatment Plant (DWTP) in Arequipa, Peru, despite often facing limitations in technical capacity and financial support in the water sector. The absence of real-time automation, insufficient skilled personnel, and inadequate maintenance hinder effective process control, reducing the efficiency and sustainability of water management systems.

By leveraging data-driven predictive analytics, this methodology significantly enhances operational resilience and sustainability, a critical advancement for resource-constrained settings where rapid and accurate responses to variable water quality are essential. The RF model’s efficiency in handling complex, high-dimensional water quality data underscores its suitability for real-time dosing optimization, reducing reliance on labor-intensive and costly conventional jar tests.

Statistical analyses revealed key operational efficiencies that informed model development. Correlation analysis identified strong interdependencies among physicochemical parameters, with high positive correlations (R = 0.85 for total dissolved solids [TDS], R = 0.69 for electrical conductivity [EC], R = 0.78 for alkalinity [Alc_CO3], and R = 0.78 for calcium hardness [Ca2+]). These findings indicate substantial redundancy among these variables, enabling the strategic reduction in preliminary raw water analyses to streamline the treatment process. By eliminating redundant predictors, the RF model minimizes computational complexity while maintaining predictive accuracy, thereby accelerating the DWTP’s response capabilities. Furthermore, Student’s t-tests confirmed the high significance of temperature (Temp_C, t-value = 7.82 × 10−8) and conductivity (EC_µS/cm, t-value = 4.01 × 10−4) as predictors. Temperature influences floc stability and settling dynamics, while conductivity affects particle surface charges, both critical for effective coagulation–flocculation processes. These results highlight the necessity of continuous monitoring of these parameters to ensure precise dosing control, particularly in environments with pronounced seasonal water quality variability.

The RF model, developed using a univariate approach focused on settled water turbidity, deliberately simplifies the model structure compared to complex multivariate frameworks, enhancing its practical applicability and reducing computational demands. The model achieved exceptional predictive accuracy within the DWTP’s typical operational range (0–2 NTU), as evidenced by a coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.92) during training, with minimal errors (root mean square error [RMSE] = 0.11 NTU, mean absolute percentage error [MAPE] = 0.11). These metrics confirm the model’s ability to maintain compliance with potable water standards (turbidity < 2 NTU) under normal conditions. In the validation phase, the R

2 decreased to 0.76 (RMSE = 0.19, MAPE = 0.20), a common outcome in machine learning models when encountering unseen data complexity. Nevertheless, the low error margins demonstrate the model’s robustness and reliability for practical applications, providing precise coagulant dosing with minimal uncertainty, even in resource-constrained settings [

38,

41].

In conclusion, this study validates the RF model, integrated into a computational platform that generates real-time dosage curves, as an efficient and effective tool for optimizing coagulant dosing at the Miguel de la Cuba Ibarra DWTP. This innovative approach empowers technical teams to implement data-driven dosing strategies, significantly reducing errors and operational costs associated with traditional jar testing while enhancing process efficiency. The platform’s ability to simulate multiple dosing scenarios in real time supports rapid adaptation to fluctuating water quality, a critical advantage in regions with limited resources and high seasonal variability [

30,

39]. The primary limitation of the model lies in its reduced performance for extreme high-turbidity events (e.g., 500–3600 NTU during January and February), attributed to data imbalance in the training set. Future research should prioritize expanding the dataset to include a broader range of high-turbidity conditions to enhance the model’s generalization capabilities during seasonal peaks. Additionally, integrating advanced feature engineering techniques or hybrid machine learning approaches could further improve predictive performance, ensuring scalability and adaptability for other DWTPs facing similar challenges [

10]. This work establishes a scalable framework for data-driven water treatment optimization, offering a model for sustainable water management in resource-constrained regions worldwide.