Assessing the Impacts of Urban Expansion and Climate Variability on Water Resource Sustainability in Chihuahua City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

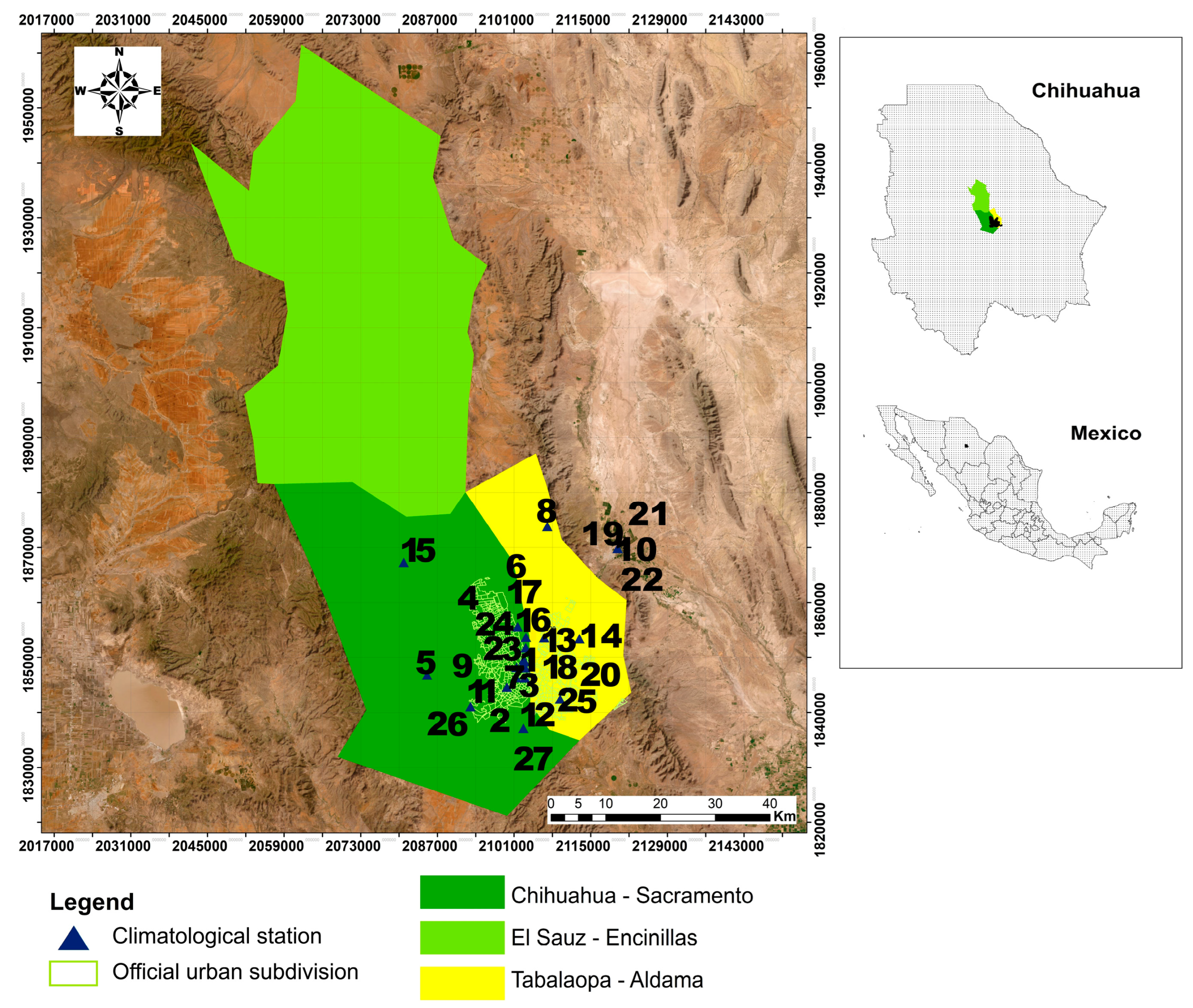

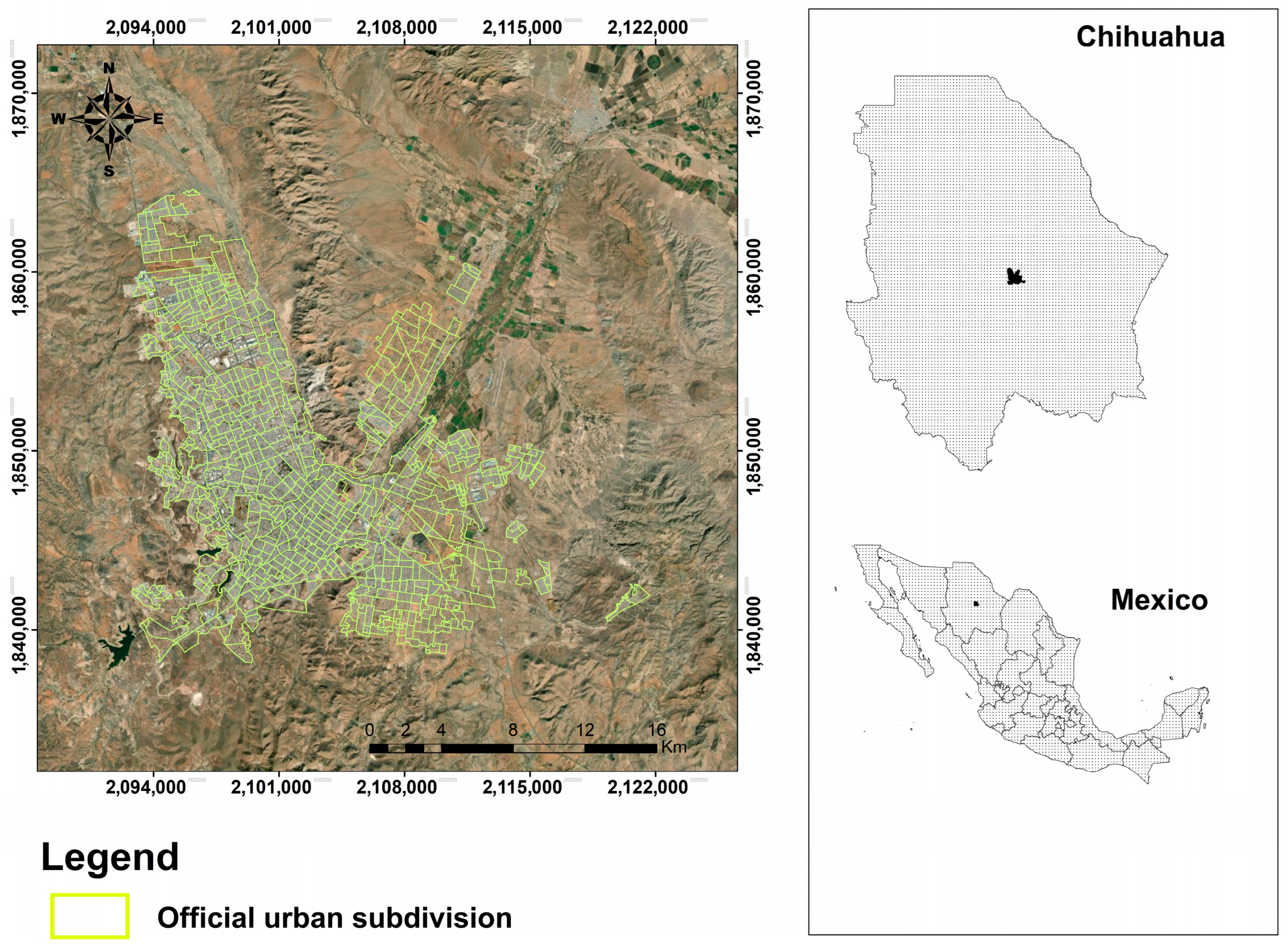

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Information: Land Use, Climate Variables, and Population Water Consumption

2.2.1. Historical Data on Population Land Use

2.2.2. Climate Variability

2.2.3. Water Requirements

2.3. Data Analysis

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Growth and Land Use Evolution

3.2. Climatic Variability in the Urban Environment

3.3. Urban Water Consumption

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Climatic and Urban Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Climatological Stations and Aquifers

Appendix A.2. Evapotranspiration Methodology

Appendix A.3. Extreme Temperature Adjustment Model: Arima and ARCH-GARCH

- Trend Analysis of Extreme Temperatures

| Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| b0 | 3.034 × 101 | 3.333 × 10−1 | 91.038 | <2 × 10−16 *** |

| b1 | 3.950 × 10−3 | 7.878 × 10−4 | 5.014 | 6.69 × 10−7 *** |

| code: 0 ***. |

- ARIMA Model Tuning (p,d,q) for Extreme Tmax

| φ1 | φ2 | φ3 | θ1 | θ2 | µ | |

| 2.1339 | −1.6963 | 0.4022 | −1.7152 | 0.9999 | 31.7862 | |

| s.e. | 0.0342 | 0.0592 | 0.0342 | 0.0094 | 0.0108 | 0.1215 |

- Fit the ARIMA Model (P,d,q) for Extreme Tmin

| φ1 | φ2 | θ1 | θ2 | µ | |

| 1.7319 | −0.9999 | −1.7019 | 0.9843 | 4.1113 | |

| s.e. | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0085 | 0.0096 | 0.1139 |

Appendix A.4. Gamma Distribution for Precipitation Analysis

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Population Growth and Urban Area Evolution

Appendix B.2. Land Use Evolution by Period

| 2005 | Total (ha) | Lost (ha) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Human Settlement | Scrub | Pastureland | ||||

| 1992 | Agriculture | 1919 | 2225 | 200 | 0 | 4344 | 2425 |

| Human settlement | 0 | 10,980 | 0 | 0 | 10,980 | 0 | |

| Scrub | 1251 | 13,321 | 6557 | 23 | 21,152 | 14,595 | |

| Pastureland | 97 | 0 | 77 | 253 | 427 | 174 | |

| Total (ha) | 3267 | 26,526 | 6834 | 276 | 36,903 | ||

| Profit (ha) | 1348 | 15,546 | 277 | 23 | |||

| 2018 | Total (ha2) | Lost (ha) | |||||

| Agriculture | Human settlement | Scrub | Pastureland | ||||

| 2005 | Agriculture | 0 | 3268 | 0 | 0 | 3268 | 3268 |

| Human settlement | 0 | 18,763 | 0 | 0 | 18,763 | 0 | |

| Scrub | 0 | 6834 | 0 | 0 | 6834 | 6834 | |

| Pastureland | 0 | 276 | 0 | 0 | 276 | 276 | |

| Total (ha) | 0 | 29,141 | 0 | 0 | 29,141 | ||

| Profit (ha) | 0 | 10,378 | 0 | 0 | |||

Appendix B.3. Statistical Results of Climate Variables

| accum_P (mm) | s_accum_P (mm) | Tm (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tmax_s (°C) | Tmin (°C) | Tmin_w (°C) | ETR (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 394.7 | 293.6 | 17.1 | 31.8 | 35.6 | 4.1 | −4.8 | 389 | |

| Med | 407.7 | 276.7 | 1.2 | 31.9 | 36.0 | 4.2 | −4.6 | 410 |

| Max | 664.6 | 546.5 | 1.5 | 34.2 | 38.5 | 7.5 | 0.5 | 611 |

| Min | 148.3 | 96.6 | 7.2 | 29.1 | 33.0 | 0.3 | −11.3 | 155 |

| σ | 116.1 | 93 | 15.7 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 102 |

| CV | 29.4 | 31.68 | 21.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 38.0 | 45.7 | 26 |

| Max | min | med | σ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | Tmin | Tmax | Tmin | Tmax | Tmin | Tmax | Tmin | Tmax | Tmin | |

| Jan | 29.2 | 0.0 | 20.0 | −16.0 | 25.1 | −4.9 | 25.3 | −5.4 | 1.9 | 2.9 |

| Feb | 33.4 | 2.2 | 23.0 | −15.8 | 27.2 | −4.2 | 27.8 | −4.3 | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| Mar | 37.0 | 4.0 | 26.0 | −14.0 | 31.0 | −1.3 | 30.7 | −1.5 | 2.1 | 3.4 |

| Apr | 39.0 | 8.8 | 30.0 | −1.0 | 33.6 | 4.2 | 33.4 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| May | 39.8 | 13.2 | 31.4 | 2.0 | 37.0 | 8.3 | 36.7 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Jun | 41.0 | 18.6 | 34.0 | 5.3 | 37.7 | 13.0 | 38.0 | 12.6 | 1.5 | 3.8 |

| Jul | 40.5 | 19.0 | 32.0 | 9.0 | 36.6 | 15.7 | 36.4 | 15.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Aug | 39.6 | 17.8 | 28.4 | 5.5 | 35.0 | 14.3 | 34.8 | 14.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Sep | 39.2 | 15.6 | 29.0 | −2.9 | 33.8 | 10.7 | 33.3 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| Oct | 35.0 | 10.0 | 28.3 | −3.0 | 31.6 | 4.6 | 31.5 | 3.9 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| Nov | 33.0 | 2.3 | 25.0 | −7.3 | 28.1 | −2.0 | 28.2 | −2.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Dec | 30.0 | 4.8 | 22.0 | −12.0 | 25.6 | −5.0 | 25.6 | −4.7 | 1.9 | 3.1 |

| Month | (mm) | σ (mm) | CV (%) | med (mm) | Max (mm) | M_occurrence (Year) | min (mm) | m_occurrence (Year) | Ca | Ck |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 7.8 | 12.0 | 150 | 2.4 | 53.9 | 1992 | 0.0 | 8 years | 2.0 | 6.6 |

| Feb | 4.6 | 7.7 | 170 | 0.8 | 39.9 | 1973 | 0.0 | 13 years | 2.4 | 9.3 |

| Mar | 5.2 | 10.0 | 190 | 1.4 | 57.9 | 2004 | 0.0 | 16 years | 3.3 | 15.4 |

| Apr | 8.6 | 12.7 | 150 | 2.9 | 66.0 | 1987 | 0.0 | 13 years | 2.3 | 9.1 |

| May | 15.8 | 19.4 | 122.3 | 10.2 | 95.4 | 1976 | 0.0 | 4 years | 2.1 | 7.7 |

| Jun | 36.7 | 34.6 | 90 | 29.5 | 162.5 | 1966 | 0.0 | 2005 | 1.4 | 4.9 |

| Jul | 95.0 | 56.0 | 60 | 82.9 | 263.3 | 2013 | 18.9 | 1980 | 1.1 | 3.8 |

| Aug | 97.1 | 51.5 | 50 | 89.9 | 196.0 | 1963 | 12.2 | 2020 | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Sep | 76.2 | 55.4 | 70 | 64.7 | 266.5 | 1978 | 6.3 | 2001 | 1.3 | 4.8 |

| Oct | 22.6 | 22.9 | 100 | 14.9 | 100.5 | 1971 | 0.0 | 2020 | 1.3 | 4.3 |

| Nov | 10.1 | 14.7 | 150 | 5.9 | 79.2 | 1985 | 0.0 | 10 years | 2.5 | 10.4 |

| Dec | 10.5 | 12.6 | 120 | 3.4 | 44.9 | 1982 | 0.0 | 6 years | 1.0 | 2.6 |

| Precipitation (mm) for Probability Levels | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | 10% | 30% | 50% | 70% | 90% | |||||

| Quantile | Gamma | Quantile | Gamma | Quantile | Gamma | Quantile | Gamma | Quantile | Gamma | |

| Jan | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 24.4 | 25.0 |

| Feb | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 14.1 | 16.1 |

| Mar | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 7.5 | 14.9 | 19.3 |

| Apr | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 9.1 | 12.1 | 25.0 | 29.1 |

| May | 0.3 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 18.1 | 19.9 | 38.6 | 41.5 |

| Jun | 3.4 | 3.4 | 14.1 | 12.4 | 29.5 | 24.8 | 40.0 | 44.0 | 84.0 | 85.8 |

| Jul | 43.8 | 35.7 | 60.5 | 61.2 | 82.9 | 85.0 | 105.2 | 114.4 | 168.0 | 167.3 |

| Aug | 38.7 | 36.3 | 57.0 | 62.4 | 89.9 | 86.8 | 123.2 | 116.9 | 179.7 | 171.2 |

| Sep | 20.8 | 18.9 | 38.5 | 40.4 | 64.7 | 63.0 | 97.8 | 93.0 | 150.2 | 150.6 |

| Oct | 0.1 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 31.2 | 28.2 | 52.7 | 60.2 |

| Nov | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 25.3 | 32.9 |

| Dec | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 30.0 | 30.1 |

References

- Gleeson, T.; Wada, Y.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Beek, L.P.H. Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature 2012, 488, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; Green, P.; Salisbury, J.; Lammers, R.B. Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth. Science 2000, 289, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaminé, H.I.; Afonso, M.J.; Barbieri, M. Advances in Urban Groundwater and Sustainable Water Resources Management and Planning: Insights for Improved Designs with Nature, Hazards, and Society. Water 2022, 14, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Social Report 2024. Social Development in Times of Converging Crises: A Call for Global Action; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. pp 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024, Online Edition; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Amparo-Salcedo, M.; Pérez-Gimeno, A.; Navarro-Pedreño, J. Water Security Under Climate Change: Challenges and Solutions Across 43 Countries. Water 2025, 17, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, V.; Poelmans, L.; Van Rompaey, A.; Dendoncker, N. The impact of urbanization on agricultural dynamics: A case study in Belgium. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, T.I.E.; Eisner, S.; Wada, Y.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Ward, P.J. Sensitivity of water scarcity events to ENSO-driven climate variability at the global scale. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 4081–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renteria-Villalobos, M.; Hanson, R.T.; Eastoe, C. Evaluation of climate variability on sustainability for transboundary water supply in Chihuahua, Mexico. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 44, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisor, A.C.; Touma, D.; Singh, D.; Jones, J.H. To understand climate change adaptation, we must characterize climate variability: Here’s how. One Earth 2023, 6, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langridge, R.; Van Schmidt, N.D. Groundwater and Drought Resilience in the SGMA Era. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzwald, K.; Lenssen, N. The importance of internal climate variability in climate impact projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2208095119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulises, R.S.H.; Lucia, F.M.A.; Delia, O.B.A.; Odila, D.l.T.V. Impacts of Climate Change on the Water Sector in Mexico. Asian J. Environ. Ecol. 2022, 17, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Aguilera, R.A.; Escolero, O.; Alcocer, J.; Correa Metrio, A.; Vilaclara, G.; Lozano García, S. Long-term responses of maar lakes water level to climate and groundwater variability in central Mexico. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2024, 139, 104861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pizza, D.M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.A.; Gonzalez-Manzano, E. Linking climate change to urban planning through vulnerability assessment: The case of two cities at the Mexico-US border. Urban Clim. 2023, 51, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; Herrera, E.; Navarro, C.J. Chihuahua-Sacramento and Tabalaopa-Aldama aquifers of Chihuahua state, Mexico: Linkage and importance of geostatistical and hydrogeochemical analysis. Water Pract. Technol. 2021, 17, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.H.; Navarro-Gómez, C.J.; Rentería, M.; Rose, J.F.; Sánchez-Navarro, J.R. Evolution of the groundwater system in the Chihuahua-Sacramento aquifer due to climatic and anthropogenic factors. J. Water Clim. Change 2021, 13, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.A.; Meza, F.J.; Varady, R.G.; Tiessen, H.; McEvoy, J.; Garfin, G.M.; Wilder, M.; Farfán, L.M.; Pablos, N.P.; Montaña, E. Water Security and Adaptive Management in the Arid Americas. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.D.; Rogelj, J.; von Schuckmann, K.; Trewin, B.; Allen, M.; Andrew, R.; Betts, R.A.; Borger, A.; Boyer, T.; Broersma, J.A.; et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2023: Annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2625–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Khan, A.; Anand, P.; Sen, J. Understanding the synergy between heat waves and the built environment: A three-decade systematic review informing policies for mitigating urban heat island in cities. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.S.; Hanson, R.T. Conjunctive Water Management; The Groundwater Project: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2025. Available online: https://gw-project.org/books/conjunctive-water-management/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- INEGI. Censos y Conteos de Población y Vivienda 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goodell, P.C. Chihuahua city uranium province, Chihuahua, Mexico. In Proceedings of the Technical Committee Meeting on Uranium Deposits in Volcanic Rocks, El Paso, TX, USA, 2–5 April 1984; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 1985; pp. 97–124. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Clave Geoestadística 08019; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Conagua. Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en el Acuífero Chihuahua-Sacramento (0830), Estado de Chihuahua; Conagua: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 1–31. Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/Edos_Acuiferos_18/chihuahua/DR_0830.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Conagua. Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en el Acuífero Tabalaopa-Aldama (0835), Estado de Chihuahua; Conagua: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/Edos_Acuiferos_18/chihuahua/DR_0835.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Conagua. Actualización de la Disponibilidad Media Anual de Agua en el Acuífero El Sauz-Encinillas (0807), Estado de Chihuahua; Conagua: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; Available online: https://sigagis.conagua.gob.mx/gas1/Edos_Acuiferos_18/chihuahua/DR_0807.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto Nacional de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación a Escala 1:250,000, Serie VII; DGG-INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Conjunto Nacional de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación a Escala 1:250,000, Serie III; DGG-INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI. Conjunto Nacional de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación a Escala 1:250,000, Serie I; DGG-INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pontius, R.G.; Shusas, E.; McEachern, M. Detecting important categorical land changes while accounting for persistence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 101, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paegelow, M.; Mas, J.-F.; Gallardo, M.; Camacho Olmedo, M.T.; García-Álvarez, D. Pontius Jr. Methods Based on a Cross-Tabulation Matrix to Validate Land Use Cover Maps. In Land Use Cover Datasets and Validation Tools: Validation Practices with QGIS; García-Álvarez, D., Camacho Olmedo, M.T., Paegelow, M., Mas, J.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 153–187. [Google Scholar]

- SMN-Conagua. Normales Climatológicas por Estado; Nacional, S.M., Ed.; Comisión Nacional del Agua: Coyoacán, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gudulas, K.; Voudouris, K.; Soulios, G.; Dimopoulos, G. Comparison of different methods to estimate actual evapotranspiration and hydrologic balance. Desalination Water Treat. 2013, 51, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. ArcGIS 10.3. 1; Environmental Systems Research Institute Redlands: Redlands, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Pineda, J.A. A Geophysical, Geochemical and Remote Sensing Investigation of the Water Resources at the City of Chihuahua, Mexico. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.A. Consumen Chihuahuenses 370 Litros de Agua al día, in Diario de Chihuahua; Diario de Chihuahua: Chihuahua, Mexico, 2023; Available online: https://diario.mx/estado/2023/feb/10/consumen-chihuahuenses-370-litros-de-agua-al-dia-928916.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Cryer, J.D.; Chan, K.S. Time Series Analysis with Applications in R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Modarres, R.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J. Modeling the relationship between climate oscillations and drought by a multivariate GARCH model. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romilly, P. Time series modelling of global mean temperature for managerial decision-making. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 76, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renteria-Villalobos, M.; Hanson, R.T. Capturing wetness for sustainability from climate variability and change in the Rio Conchos, Chihuahua, Mexico. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.T.; Dettinger, M.D.; Newhouse, M.W. Relations between climatic variability and hydrologic time series from four alluvial basins across the southwestern United States. Hydrogeol. J. 2006, 14, 1122–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husak, G.J.; Michaelsen, J.; Funk, C. Use of the gamma distribution to represent monthly rainfall in Africa for drought monitoring applications. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangela, G.L.C.d.; Silva, M.V.d.; Araújo Júnior, G.d.N.; Silva, J.R.I.d.; França e Silva, Ê.F.d.; Pandorfi, H.; Morales, K.R.M.; Vasconcelos, C.; Massinga, A.P.; Mabasso, G.A.; et al. Temporal dynamics of rainfall using the gamma distribution for the municipality of Chimoio, Mozambique. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2023, 16, 1072–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanos, A. Univariate GARCH Models. Package ‘rugarch’, Version 1.5-4; CRAN_R Package: New Zealand, 2025; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rugarch/rugarch.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Amburn, S.A.; Lang, A.S.I.D.; Buonaiuto, M.A. Precipitation Forecasting with Gamma Distribution Models for Gridded Precipitation Events in Eastern Oklahoma and Northwestern Arkansas. Weather. Forecast. 2015, 30, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.-D.; Hou, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, P.-C. Sensitivity analysis of standardized precipitation index to climate state selection in China. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2022, 13, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Li, X.; Bardgett, R.D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Revillini, D.; Sonne, C.; Xia, C.; Ruan, H.; Liu, Y.; Cao, F.; et al. Deforestation impacts soil biodiversity and ecosystem services worldwide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2318475121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B. La política exterior de México durante el gobierno de Luis Echeverría (1970–1976): El renovado activismo global. Foro Int. 2022, 62, 677–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Huerta, E.; Rosas-Casals, M.; Hernández-Terrones, L.M. A water balance model to estimate climate change impact on groundwater recharge in Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2020, 65, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, R.A.; Corona, E.A.Z.; Pinedo, A.A.; Jiménez, G.R.; Pinedo, C.A.; Rojas, R.I.C.; Ranfla, A.G. Marginación y cambio de cobertura y uso del suelo de la zona metropolitana de Chihuahua. Investig. Cienc. Univ. Autónoma Aguascalientes 2016, 67, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biney, E.; Mintah, B.A.; Ankomah, E.; Agbenorhevi, A.E.; Yankey, D.B.; Annan, E. Sustainability assessment of groundwater in south-eastern parts of the western region of Ghana for water supply. Clean. Water 2024, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila Rodríguez, A.; Alatorre Cejudo, L.C.; Bravo-Peña, L.C. Análisis de la evolución espacio-temporal del uso de suelo urbano en la metrópolis de Chihuahua. Econ. Soc. Territ. 2021, 21, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Abraham, J.; Trenberth, K.E.; Boyer, T.; Mann, M.E.; Zhu, J.; Wang, F.; Yu, F.; Locarnini, R.; Fasullo, J.; et al. New Record Ocean Temperatures and Related Climate Indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Sorte, F.A.; Johnston, A.; Ault, T.R. Global trends in the frequency and duration of temperature extremes. Clim. Change 2021, 166, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; He, P.; Li, Z.; Shi, M.; Xu, J. Spatiotemporal variability characteristics of extreme climate events in Xinjiang during 1960–2019. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 57316–57330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bueno, J.A.; Díaz, J.; Follos, F.; Vellón, J.M.; Navas, M.A.; Culqui, D.; Luna, M.Y.; Sánchez-Martínez, G.; Linares, C. Evolution of the threshold temperature definition of a heat wave vs. evolution of the minimum mortality temperature: A case study in Spain during the 1983–2018 period. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Risser, M.D.; Wehner, M.F.; O’Brien, T.A. Leveraging Extremal Dependence to Better Characterize the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMPLAN. Fifth Update of the Urban Development Plan for the City of Chihuahua, Vision 2040 (PDU2040); Instituto Municipal de Planeación: Chihuahua, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bücher, A.; Jennessen, T. Statistics for heteroscedastic time series extremes. Bernoulli 2024, 30, 26, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Zhan, M.; Xu, B.; Li, H.; Zhan, L. Variations of Extreme Temperature Event Indices in Six Temperature Zones in China from 1961 to 2020. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerano-Paredes, J.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Fulé, P.Z.; Arreola-Ávila, I.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.D. Reconstrucción de 350 años de precipitación para el suroeste de Chihuahua, México. Madera Y Bosques 2009, 15, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazel, A.; Gober, P.; Lee, S.; Grossman-Clarke, S.; Zehnder, J.; Hedquist, B.; Comparri, E. Determinants of changes in the regional urban heat island in metropolitan Phoenix (Arizona, USA) between 1990 and 2004. Clim. Res. 2007, 33, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman-Clarke, S.; Zehnder, J.A.; Loridan, T.; Grimmond, C.S.B. Contribution of Land Use Changes to Near-Surface Air Temperatures during Recent Summer Extreme Heat Events in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2010, 49, 1649–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Ortíz, A.I. Indicadores Base de Adaptación al Cambio Climático en la Ciudad de Chihuahua. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autonoma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Gu, X.; Lv, N.; Guan, Y.; Kong, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Elevated increases in human-perceived winter temperature in urban areas over China: Acceleration by urbanization. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zubaidi, S.L.; Ortega-Martorell, S.; Al-Bugharbee, H.; Olier, I.; Hashim, K.S.; Gharghan, S.K.; Kot, P.; Al-Khaddar, R. Urban Water Demand Prediction for a City That Suffers from Climate Change and Population Growth: Gauteng Province Case Study. Water 2020, 12, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, S.; Douglas, M.W.; Maddox, R.A. El monzón del suroeste de Norteamérica (TRAVASON/SWAMP). Atmósfera 1994, 7, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pascale, S.; Bordoni, S.; Kapnick, S.B.; Vecchi, G.A.; Jia, L.; Delworth, T.L.; Underwood, S.; Anderson, W. The Impact of Horizontal Resolution on North American Monsoon Gulf of California Moisture Surges in a Suite of Coupled Global Climate Models. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 7911–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Pandey, K.K. Spatiotemporal variability identification and analysis for non-stationary climatic trends for a tropical river basin of India. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Statistical Analysis and Stochastic Modelling of Hydrological Extremes. Water 2019, 11, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.F.; Gu, G. Global Precipitation for the Year 2023 and How It Relates to Longer Term Variations and Trends. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Yin, J.; Gentine, P.; Wang, H.-M.; Slater, L.J.; Sullivan, S.C.; Chen, J.; Zscheischler, J.; Guo, S. Large anomalies in future extreme precipitation sensitivity driven by atmospheric dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, R.H.; Brizuela, N.G.; Matijevic, B.J.; Vizzard, J.V.; Agostino, C.P.; Lutsko, N.J. Projected Changes in Mean and Extreme Precipitation over Northern Mexico. J. Clim. 2024, 37, 2405–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.H.; Navarro-Gómez, C.J.; Rentería, M.; Sánchez-Navarro, J.R. Saving water by returning to a constant water supply in Chihuahua. Water Int. 2023, 48, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyambo, F.; Belle, J.; Nyam, Y.S.; Orimoloye, I.R. Climate-Change-Induced Weather Events and Implications for Urban Water Resource Management in the Free State Province of South Africa. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasifaghihi, N.; Li, S.S.; Haghighat, F. Forecast of urban water consumption under the impact of climate change. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkić, D. Temperature Impact on Drinking Water Consumption. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2020, 2, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrin, Z.; Hamidi, O.; Amini, P.; Maryanaji, Z. Predicting the pulse of urban water demand: A machine learning approach to deciphering meteorological influences. BMC Res. Notes 2024, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, O. The relationship between climate conditions and consumption of bottled water: A potential link between climate change and plastic pollution. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1992 | 2005 | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Type | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % | Area (ha) | % |

| Agriculture | 4344 | 12% | 3268 | 9% | 0 | 0% |

| Human settlements | 10,980 | 30% | 26,526 | 72% | 36,913 | 100% |

| Pastureland | 427 | 1% | 276 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| Scrub | 21,152 | 57% | 6834 | 19% | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 36,903 | 100% | 36,913 | 100% | 36,913 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rentería-Villalobos, M.; Díaz-García, J.A.; Mendieta-Mendoza, A.; Barraza Jiménez, D. Assessing the Impacts of Urban Expansion and Climate Variability on Water Resource Sustainability in Chihuahua City. Environments 2026, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010014

Rentería-Villalobos M, Díaz-García JA, Mendieta-Mendoza A, Barraza Jiménez D. Assessing the Impacts of Urban Expansion and Climate Variability on Water Resource Sustainability in Chihuahua City. Environments. 2026; 13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleRentería-Villalobos, Marusia, José A. Díaz-García, Aurora Mendieta-Mendoza, and Diana Barraza Jiménez. 2026. "Assessing the Impacts of Urban Expansion and Climate Variability on Water Resource Sustainability in Chihuahua City" Environments 13, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010014

APA StyleRentería-Villalobos, M., Díaz-García, J. A., Mendieta-Mendoza, A., & Barraza Jiménez, D. (2026). Assessing the Impacts of Urban Expansion and Climate Variability on Water Resource Sustainability in Chihuahua City. Environments, 13(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010014