The Conservation of the Endangered Monachus monachus: Could Maritime Workers Contribute to Its Study?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profiles of Maritime Workers

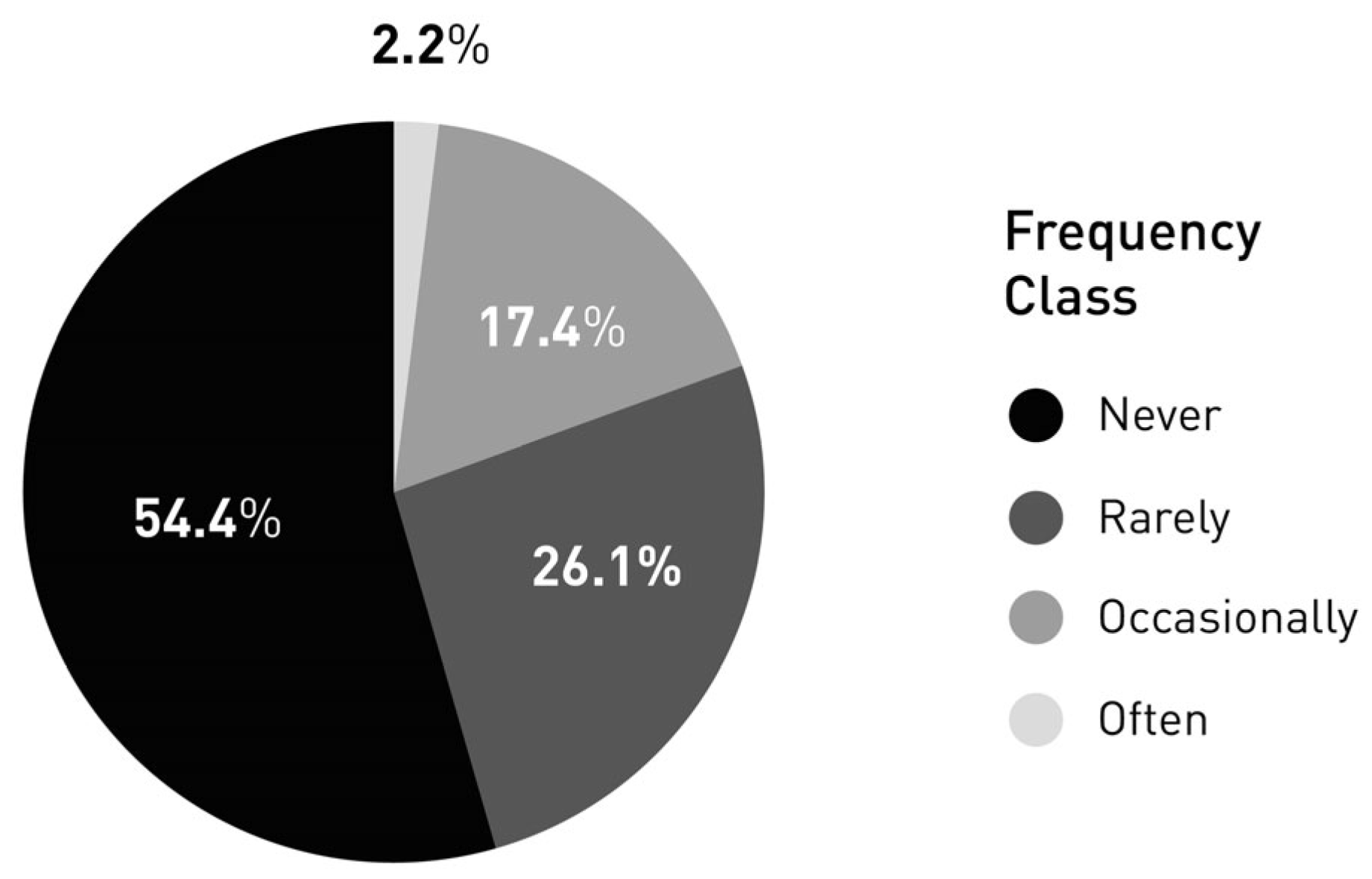

3.2. Workers’ Perceptions of Presence and Observed Frequency of Occurrence of Monk Seals at Fish Farms

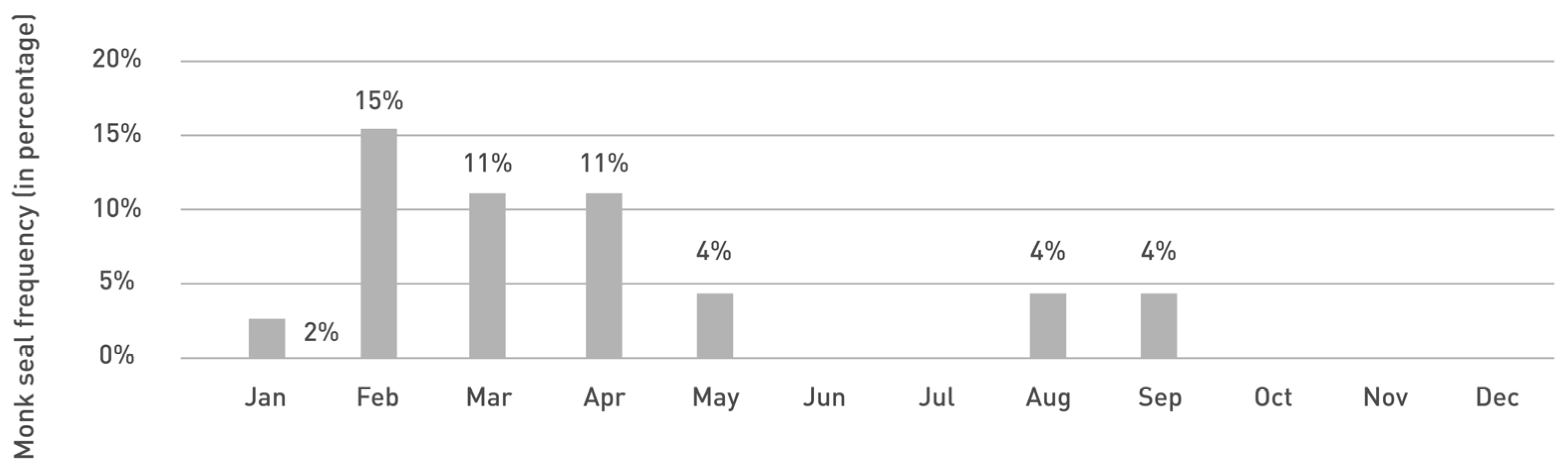

3.3. Workers’ Perceptions of Monk Seal’s Seasonality of Occurrence in Madeira’s Fish Farms

3.4. Perception of Fish Farms’ Effects on Monk Seals and Worker Profiles Shaping These Views

3.5. Assessing Animosity Toward Monk Seals and Aquaculture Industry

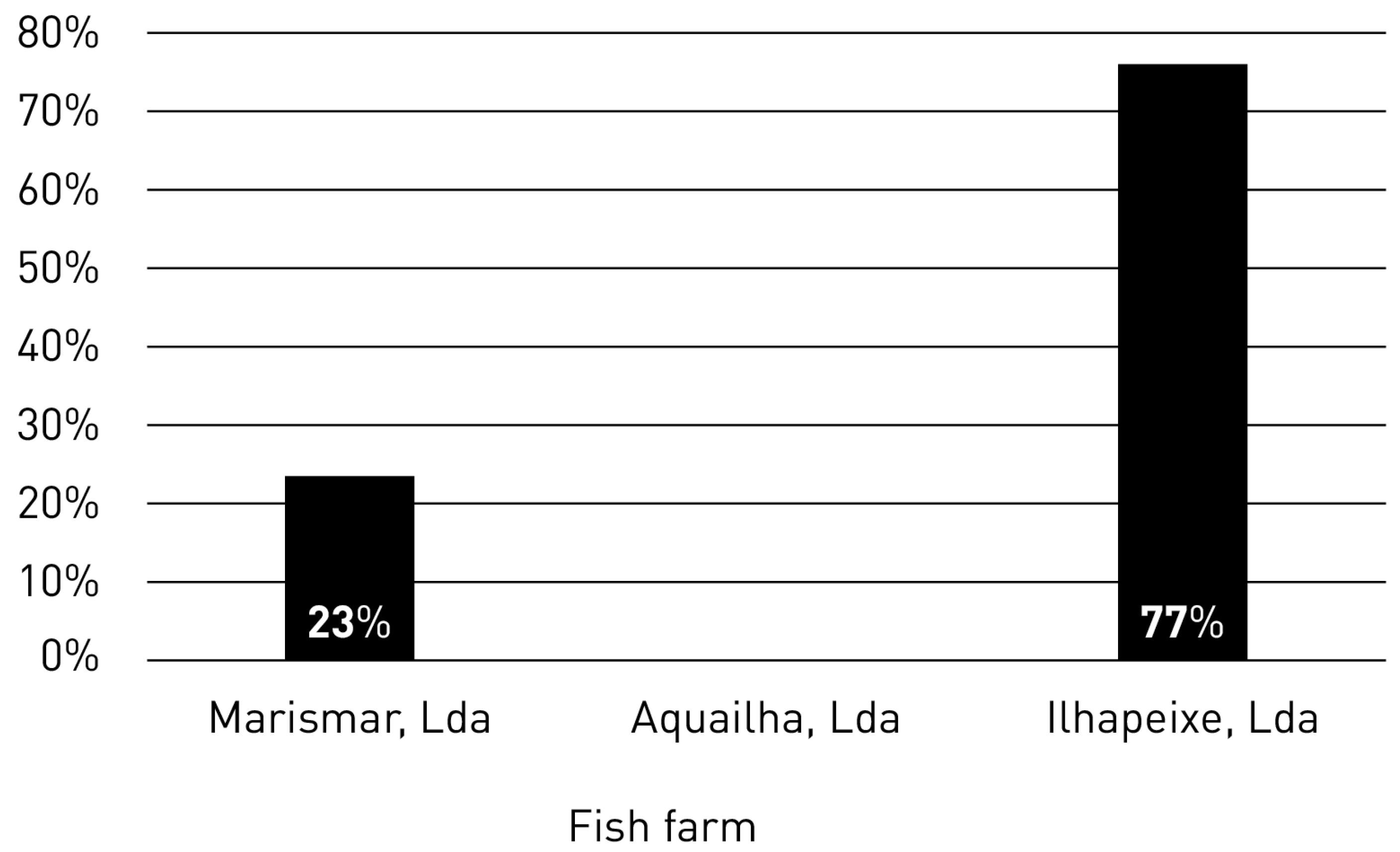

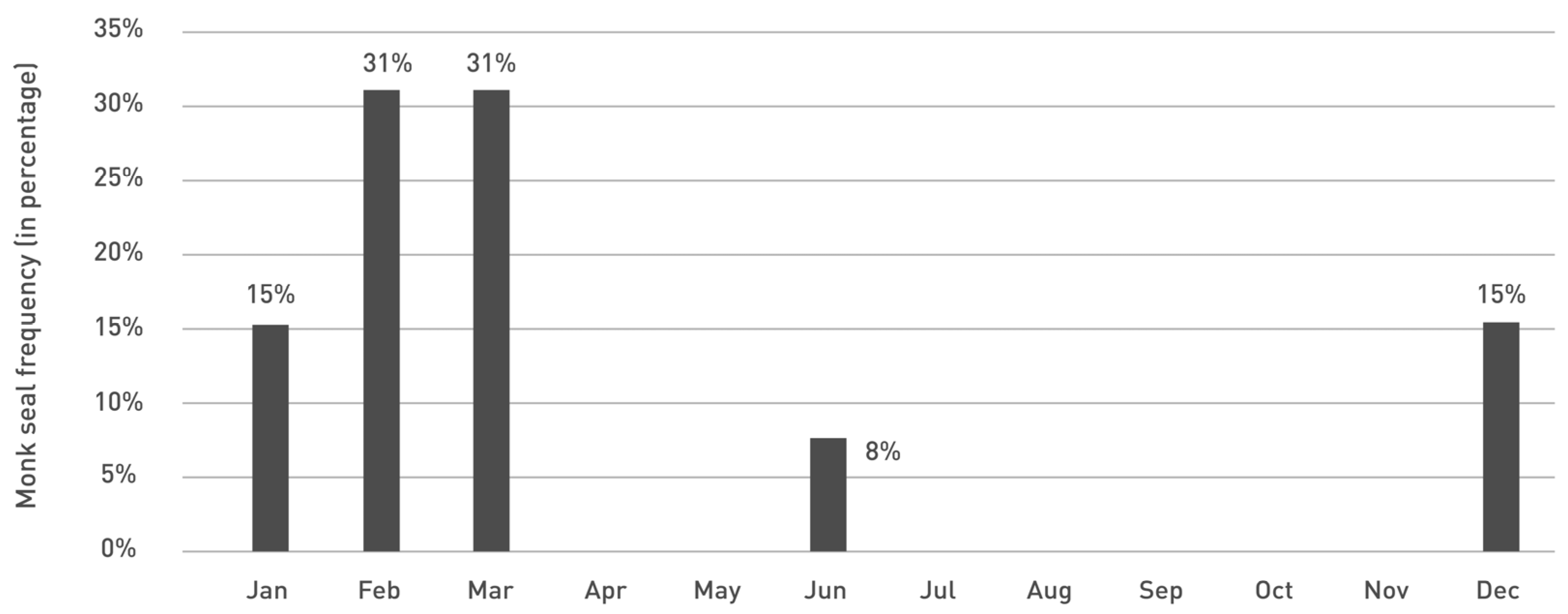

3.6. Presence and Frequency of Occurrence of Monk Seals at Fish Farms Observed On-Site

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pires, R.; Aparicio, F.; Baker, J.D.; Pereira, S.; Caires, N.; Cedenilla, M.A.; Harting, A.L.; Menezes, D.; de Larrinoa, P.F. First demographic parameter estimates for the Mediterranean monk seal population at Madeira, Portugal. Endanger. Species Res. 2023, 51, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanlidis, A.; Dendrinos, P. Monachus monachus, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/13653/0 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Karamanlidis, A.A. Current status, biology, threats and conservation priorities of the Vulnerable Mediterranean monk seal. Endanger. Species Res. 2024, 53, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, R.; Aparicio, F.; Fernandez De Larrinoa, P. Estratégia para a Conservação do Lobo-Marinho no Arquipélago da Madeira. 2020. Available online: https://ifcn.madeira.gov.pt/images/Doc_Artigos/Biodiversidade/Projetos/lobomarinho/Estrategia_para_a_Conservacao_do_Lobo-marinho_na_Madeira.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Hale, R. Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus): Fishery Interactions in the Archipelago of Madeira. Aquat. Mamm. 2011, 37, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S. Aquaculture: A newly emergent food production sector—And perspectives of its impacts on biodiversity and conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 3187–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlüsoy, H.; Savas, Y. Interaction between monk seals Monachus monachus (Hermann, 1779) and marine fish farms in the Turkish Aegean and management of the problem. Aquac. Res. 2003, 34, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parretti, P.; Monteiro, J.G.; Gizzi, F.; Martínez-Escauriaza, R.; Alves, F.; Chebaane, S.; Almeida, S.; Pessanha Pais, M.; Almada, F.; Fernandez, M.; et al. Citizen Science and Expert Judgement: A Cost-Efficient Combination to Monitor and Assess the Invasiveness of Non-Indigenous Fish Escapees. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C.M.; William Cawthorn Cawthorn, M.; Heinrich, S.; Pemberton, D.; Cawthorn, M.; Mann, J.; Würsig, B.; Shaughnessy, P.; Gales, R. Aquaculture and marine mammals: Co-existence or conflict? In Marine mammals: Fisheries, Tourism, and Management Issues; CSIRO: Collingwood, Australia, 2003; pp. 208–225. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260392957 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Nash, C.E.; Iwamoto, R.N.; Mahnken, C.V.W. Aquaculture risk management and marine mammal interactions in the Pacific Northwest. Aquaculture 2000, 183, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, D.; Shaughnessy, P.D. Interaction between seals and marine fish-farms in Tasmania, and management of the problem. Aquat. Conserv. 1993, 3, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerovasileiou, V.; Akel, E.; Akyol, O.; Alongi, G.; Azevedo, F.; Babali, N.; Bakiu, R.; Bariche, M.; Bennoui, A.; Castriota, L.; et al. New Mediterranean Biodiversity Records (July, 2017). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2017, 18, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroluongo, G.; Martín-Montalvo, B.Q.; Ashok, K.; Miliou, A.; Fosberry, J.; Antichi, S.; Moscatelli, S.; Tsimpidis, T.; Carlucci, R.; Azzolin, M. Combining Monitoring Approaches as a Tool to Assess the Occurrence of the Mediterranean Monk Seal in Samos Island, Greece. Hydrobiology 2022, 1, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliou, A.; Akkaya Ba, A.; Pietroluongo, G. Interactions between marine mammals and fisheries: Case studies from the Eastern Aegean and the Levantine Sea. In CIESM Workshop Monographs; CIESM: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. Possible Impacts of Offshore Aquaculture in Madeira Island, Portugal, on the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus). Master’s Thesis, Porto University, Porto, Portugal, 2023. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/156841/2/657462.PDF (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Quick, N.J.; Middlemas, S.J.; Armstrong, J.D. A survey of antipredator controls at marine salmon farms in Scotland. Aquaculture 2004, 230, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioinsight. Ampliação da Piscicultura Flutuante Offshore da Ribeira Brava—Estudo de Impacte Ambiental. Volume II—Relatório Síntese. 2020. Available online: https://participa.pt/contents/consultationdocument/T30-2017_EIA%20Piscicultura_Offshore_VolumeII_RS.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Amaral, A.C. Estudo da atração de focas-monge (Monachus monachus) aos estabelecimentos de piscicultura marinhas da ilha da Madeira, Portugal. Master’s Thesis, University of Évora, Évora, Portugal, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10174/31469 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Pires, R. (Serviço de Ambiente e Alterações Climáticas de Santa Maria, Parque Natural de Santa Maria, Vila do Porto, Portugal). Agreement of Understanding for Collaboration. Unpublished Document. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Viena, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ccen (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Pirotta, V.; Reynolds, W.; Ross, G.; Jonsen, I.; Grech, A.; Slip, D.; Harcourt, R. A citizen science approach to long-term monitoring of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) off Sydney, Australia. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2020, 36, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berimbau, L.; Larrea, A.; Costa, A.C.; Torres, P. Human–Shark Interactions: Citizen Science Potential in Boosting Shark Research on Madeira Island. Diversity 2023, 15, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigl, F.; Kieslinger, B.; Paul, K.; Uhlik, J.; Dörler, D. Toward an international definition of citizen science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8089–8092. Available online: https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1903393116 (accessed on 14 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorvaldsen, T.; Kongsvik, T.; Holmen, I.M.; Størkersen, K.; Salomonsen, C.; Sandsund, M.; Bjelland, H.V. Occupational health, safety and work environments in Norwegian fish farming—Employee perspective. Aquaculture 2020, 524, 735238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azores Adventures Futurismo. Encontre a Sua Viagem Perfeita. Available online: https://www.futurismo.pt/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Elding. Whale-Watching Tour. 2025. Available online: https://elding.is/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Adamantopoulou, S.; Karamanlidis, A.A.; Dendrinos, P.; Gimenez, O. Citizen science indicates significant range recovery and defines new conservation priorities for Earth’s most endangered pinniped in Greece. Anim. Conserv. 2023, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, R.; Tobeña, M.; Silva, M.A. Habitat preferences of baleen whales in a mid-latitude habitat. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2017, 141, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupman, K.; Visser, I.; Martinez, E.; Stockin, K. Using platforms of opportunity to determine the occurrence and group characteristics of orca (Orcinus orca) in the Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 2015, 49, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, M.; Tunca, S.; Martinez, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Le Gallic, B.; Brunsø, K.; Sharma, P.; Eljasik, P.; Gyalog, G.; et al. Societal perceptions of aquaculture: Combining scoping review and media analysis. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workplace | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Sector | Calheta | Machico | Ribeira Brava | Funchal | Santa Cruz |

| Fish farm workers | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Wildlife rangers | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Whale-watching staff | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Scuba diving club staff | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Professional Sector | Years in the Company (1) | Educational Level | Age (1) (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish farm workers | 5.6 | Basic school | 35.6 (22–53) |

| Wildlife rangers | 20.8 | High school | 47 (43–50) |

| Whale-watching staff | 7.1 | Bachelor’s degree | 34.4 (22–57) |

| Scuba diving club staff | 18.9 | Bachelor’s degree | 46 (26–63) |

| Main Arguments | Positive Perception | Negative Perception |

|---|---|---|

| Predictable feeding and increased prey availability | 16 | |

| Consumption of unhealthy residues (sick fish, plastic, and antibiotic-treated fish) | 5 | |

| Habituation to humans and population behavioral changes | 15 | |

| Increased vulnerability to harm or accidents | 6 | |

| Changes in habitat and its quality | 7 |

| Influencing Factor | Positive Perception | Negative Perception | Statistical Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace | High influence | Low influence | χ2 = 18.4; p < 0.001 |

| Educational level | Low influence | High influence | χ2 = 11.9; p = 0.018 |

| Years at company | Low influence | Moderate influence | F = 8.27; p = 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amaral, A.C.; Andrade, C.A.P. The Conservation of the Endangered Monachus monachus: Could Maritime Workers Contribute to Its Study? Environments 2025, 12, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060207

Amaral AC, Andrade CAP. The Conservation of the Endangered Monachus monachus: Could Maritime Workers Contribute to Its Study? Environments. 2025; 12(6):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060207

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmaral, Ana Cecília, and Carlos Alberto Pestana Andrade. 2025. "The Conservation of the Endangered Monachus monachus: Could Maritime Workers Contribute to Its Study?" Environments 12, no. 6: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060207

APA StyleAmaral, A. C., & Andrade, C. A. P. (2025). The Conservation of the Endangered Monachus monachus: Could Maritime Workers Contribute to Its Study? Environments, 12(6), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12060207