Abstract

Rising temperatures due to climate change are exacerbating the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI). UHI has serious impacts on ecosystems and human health, causes the deterioration of infrastructure and economic loss, decreases air quality, and increases energy consumption. The problem is heightened in densely populated cities. Temperatures are projected to rise more steeply in Korea than global temperatures. This paper focuses on evaluating UHI adaptation strategies of densely populated Korean cities Seoul, Busan, and Daegu through a policy review. The comparative analysis shows that, in terms of heatwave and UHI policies, Daegu is ahead as the only city with a dedicated heatwave plan. As the hottest city in Korea, it is not surprising that it is leading in heatwave policy and research. The study finds that blue–green infrastructures were the most common strategies for heatwave mitigation in these cities, but transformative adaptation is still largely absent. Despite the severity of the UHI phenomenon, particularly in densely populated Asian cities, the response so far has been limited. While there is evidence of genuine efforts towards UHI mitigation and increasing the quality and quantity of green infrastructure, many policies are too general and do not include specific details or measurable targets. Investment in expensive projects has fallen well short of the need and scale of the problem. The findings show that Korea is in the early stages of policy development for adaptation to the effects of heatwaves and UHI, and much more action is needed in the future.

1. Introduction

Heatwaves and the intensifying Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect are among the significant impacts of rising temperatures due to climate change [1], and the problem is compounded by the densification of urban centres. Changes in urban form and the land surface due to urbanization, an increase in artificial heat emission, and a decrease in green areas or water surfaces that cool the city are among the causes of the UHI effect [2]. UHI has serious impacts on ecosystems and human health, causes the deterioration of infrastructure and economic loss, decreases air quality, and increases energy consumption. This is particularly a problem in densely populated cities. The impacts of climate change are expected to intensify at the end of the 21st century. South Korea’s (hereafter Korea) temperature will rise more steeply than the global temperature rise. According to over 100 years of meteorological data from six observation stations in Korea (Seoul, Incheon, Daegu, Busan, Gangneung, and Mokpo), the average annual temperature in Korea rose by approximately 1.8 °C over 106 years from 1912 to 2017, which is significantly faster than the average global warming of 0.85 °C during the same period [3]. More recently, over the 30 years between 1988–2017, the average annual temperature rose by 1.4 °C compared to the early 20th century (1912–1941) [4] p. 6. On 7 January 2020, Jeju Island’s daytime high reached 23.6 °C, showing abnormal temperatures for the first time since 1923 [3]. In addition, on 1 August 2018, 39.6 °C was recorded in Seoul and 41 °C in Hongcheon, Gangwon Province, the highest temperature in 111 years. The number of days of heatwaves nationwide was 31.4, which was the most extended heatwave since 1973 [3], and this highlighted the need for systematic management of heat risks [5]. As a direct result of this increasing heatwave risk, the Disaster and Safety Management Basic Act was amended in September 2018. This revision officially recognised a heatwave as a natural disaster, establishing a foundational legal framework for heatwave risk management [5]. It mandates a government-level task force based on the disaster’s type and severity, ensuring coordinated mitigation efforts. It defines vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, individuals with disabilities, and low-income groups, as these populations have a higher risk due to physical, social, and economic factors [6].

The objective of this paper is to assess whether there are sufficient UHI adaptation strategies in densely populated cities in Korea and identify any policy gaps. Through reviewing UHI adaptation policies in three large Korean cities, this study aims to determine whether these policies are aligned with state-of-the-art responses identified in the literature. Identification of these gaps is the first step towards improving UHI adaptation strategies. The paper first provides an overview of climate adaptation to heatwaves and describes the methods used. It then overviews Korean national adaptation policies that are relevant to increased temperatures and heatwaves. After an introduction of the case study areas, a review of provincial and local adaptation policies is presented for each city. The paper concludes after the discussion of the findings.

2. Adaptation to Heatwaves

Climate change adaptation can be implemented through three major approaches. The coping approach focuses on reducing the short-term negative impacts of disasters and involves restoring current ways of life, incremental adaptation goes beyond coping and aims to prevent negative impacts in the short and medium term, whereas transformational adaptation includes more proactive approaches in the long-term [7]. Transformability, “the ability to transition intentionally to a new system with different structure, functions, feedback and outputs”, is what marks transformative resilience [8] p. 7. Transformative resilience involves a change from the status quo rather than protecting current ways of life and is suitable for systems facing a regime shift due to the escalating impacts of climate change. Transformative adaptation examples include radical measures such as the relocation of whole communities away from vulnerable disaster-prone areas. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Sixth Assessment Report [1] emphasizes the need for transformation to be able to mitigate and adapt effectively.

There is a wide range of strategies used to mitigate the UHI effect and heatwaves. Hintz, et al. [9] classify adaptation strategies into three categories: green/blue infrastructure, grey infrastructure, and behaviour of inhabitants. Green and blue infrastructure are nature-based solutions that aim to increase the percentage of greenspaces, vegetation, and free water to reduce urban temperature by reducing thermal pressure [10]. Green infrastructure is defined as “the nature-based systems that mimic the natural hydrology and regulate surface energy processes through evaporation, shadowing, and adjusting emissivity, and positively affecting air movement and heat exchange” whereas blue infrastructure is “the natural or man-made forms of water implemented in the city that slows runoff by providing temporary storage, emitting longwave radiation to cool surfaces, and effectively absorbing shortwave radiation and releasing it through evaporation” [11] p. 1. These include vegetation and greening at all scales, from green and blue belts to street trees; green building envelopes, including green roofs, pavements, walls, and facades; and use of water, including pavement watering. A review of solutions to urban heatwaves found that green and blue infrastructure are the most commonly used strategies worldwide [9].

Grey infrastructure focuses on building infrastructure that has cooling effects [9] and is defined as “the engineering structures or measures constructed by concrete or metals for regulating urban heat fluxes” [12] p. 12. Examples include the use of high albedo building materials, cool roofs and pavements, the use of reflective glass, and window or outdoor shading. Kumar, et al. [13] identified 51 types of green, blue, and grey infrastructure through a review of 202 papers. They found that green infrastructures, such as botanical gardens, wetlands, green walls, and street trees have the highest cooling efficiency. Other researchers have also found green and blue infrastructure to be the most effective UHI mitigating strategies [14,15].

Changes in people’s behaviour can be an important climate change adaptation strategy. Adaptive behaviours are facilitated by raising awareness of how to behave in heat (e.g., staying hydrated and in shade, wearing appropriate clothing, and avoiding certain activities), developing early warning systems, medical alerts, and emergency response capacity, and developing workplace policies [9].

In addition to these, planning responses can help cool the city mediating the impacts of both the UHI effect and heatwaves on human health. Urban form attributes such as land use mix, road density, percentage of greenspaces, and population density are strongly correlated with UHI [16]. Planning responses include measures to create cooler urban forms and built environments, developing sustainable transport systems, and vulnerability and risk mapping. Building characteristics such as size, height, width, orientation, spacing of the buildings, and ventilation can significantly affect internal temperatures [17].

Not all these responses are transformative. These measures are mapped onto the spectrum of resilience approaches (Table 1) following the examples Torabi, et al. [18] provide. Due to the complexity of the physical processes contributing to urban heat Zhao, et al. [19] argue that a multi-measure-centric whole-system approach that includes multiple strategies is required. Transformative adaptation supports this systemic approach.

Table 1.

Overview of UHI effect and heatwave adaptation measures across three key adaptation approaches (Adapted from [18] p. 299 and [20]).

3. Materials and Methods

This study used the policy review method. First, a comprehensive literature review on adaptation to UHI and heatwaves was conducted to identify a comprehensive list of adaptation strategies in four categories including green and blue infrastructure, grey infrastructure, planning responses, and behaviour of inhabitants. An evaluation framework was developed based on the main UHI adaptation strategies identified in this review. This framework was used to evaluate the policies of the Korean national government and three Korean cities: Seoul Special City, Busan Metropolitan City, and Daegu Metropolitan City. The evaluations included legislative frameworks, climate adaptation policies, UHI policies, and heatwave policies. An interview with a climate change researcher was also conducted to triangulate the findings. Interviews were also requested from various departments, including the Climate Change Response Team within the Climate and Air Quality Division of Busan Metropolitan City. They informed the research team that the UHI adaptation policy is part of the ongoing Detailed Implementation Plan for Climate Change Adaptation Measures (2022–2026). However, due to these ongoing tasks, they could not accommodate interviews.

4. Results

4.1. National Adaptation Policies

Korea undertook the task of establishing an adaptation base starting with the 3rd Comprehensive Plan on Countermeasures to Climate Change (2005–2007). Previously, the policy focused solely on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Established comprehensive measures to cope with climate change were to reflect the national climate change response strategy. On 1 July 2009, Korea’s only research institute specializing in adaptation policies, the Korea Adaptation Centre for Climate Change (KACCC), was established at the Korea Environment Institute (KEI).

Korea does not have a national UHI or heatwave policy, so adaptation strategies related to urban heat islands or heatwaves are spread across various climate change policies (Table 2). The national-level legislation that has provisions related to urban heat islands and increased temperatures include the Framework Act on Low Carbon Green Growth, a law promoting climate change impact assessment and adaptation measures; the Urban Parks and Green Areas Act; and the Act on the Creation and Management of Urban Forests. The central government of Korea establishes detailed implementation plans every five years to mitigate the climate change effect, which are implemented in all metropolitan cities.

Table 2.

Heat adaptation measures found in national policies.

Korea’s top strategy for responding to climate change and the basis for climate change adaptation measures, the Framework Act on Low Carbon Green Growth (Clause 4, Article 48 and Article 38 of Enforcement Decree), was enacted in 2010 [23]. Following the Act, the government introduced the first 5-year National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2011–2015). The vision of the plan was the establishment of a safe society and support for green growth through climate change adaptation and it consists of seven sectoral adaptation plans including health with the aim of protecting people from heatwaves and air pollution. The National Plan is a mandatory document that provides guidance for the central and local governments to map out detailed plans for implementation [23]. The second National Plan kept the public health sectoral plan aiming to establish countermeasures to protect the citizen’s lives and health from heatwaves and air pollution.

The national government and the governor have mandated the establishment and implementation of detailed plans in accordance with climate change adaptation measures. The Third National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2021–2025) of the Republic of Korea was developed through the intergovernmental collaboration of departments in 2020 [24]. Its vision is to implement a climate-safe nation with the people to create a country where people can feel safe from climate change. Its objectives include higher climate resilience in all social sectors in preparation for a 2 °C increase in global temperature, promotion of science-based adaptation by establishing climate monitoring and forecasting infrastructure, and realization of adaptation mainstreaming in which all adaptation actors participate [3].

The key strategies to achieve these objectives are the improvement of climate resilience, protection of vulnerable groups, promotion of civic participation, and response to the new climate regime. In contrast to the first and second plans this plan does not mention heatwaves directly when it discusses preparation of prevention mechanisms against health damage. The three adaptation measures listed for the health sector are broader and include: building monitoring and assessment mechanisms for assessing the impacts of climate change on health, strengthening responses to infectious diseases caused by climate change, and protecting the health of classes of people vulnerable to climate change [24]. Heatwaves are discussed under the protection of vulnerable people and the actions listed include the identification of hot spots for managing climate risks; building adaptive infrastructure such as cooling roads and cool roofs around the identified hot spots; and expansion of designation of shelters for extreme heat and cold waves. In addition, economically vulnerable groups who live in cheap lodgings will be supported by improving their living environment through the supply of window-type air conditioners, heat and cold wave response kits, and insulated windows, as well as the provision of energy vouchers. Heatwave response facilities such as cooling or trailer shelters will be provided for outdoor workers, and their working hours and break times will be adjusted during heatwaves.

Measures related to the behaviour of inhabitants include protecting vulnerable groups from climate change, managing vulnerable areas and facilities, and preventing and managing health damage. Heatwaves, which refer to very severe heat, vary in numerical definition in different countries. In Korea, a day when the maximum daily temperature is 33 °C or higher is defined as a heatwave [25]. Korea has a two-step heatwave warning system. From May 2020, a heatwave warning is issued when the maximum daily apparent temperature is expected to be 33 °C or higher for more than 2 days or significant damage is expected due to a sudden rise in perceived temperature or prolonged heatwave conditions. When the maximum daily temperature is expected to be 35 °C or higher for more than two days or when extensive damage is expected under similar conditions a heatwave alert is issued [26]. Since 2011, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCPA) has been operating an emergency room monitoring system for thermal diseases every summer from May to September and sharing information quickly to encourage the public to exercise caution and undertake prevention activities [27].

National government policies tend to be quite high level and provide guidance to lower levels of government rather than details and measurable objectives. The lack of a national UHI or heatwave policy results in a fragmented approach to adaptation that has limited effect.

4.2. Metropolitan Adaptation Policies

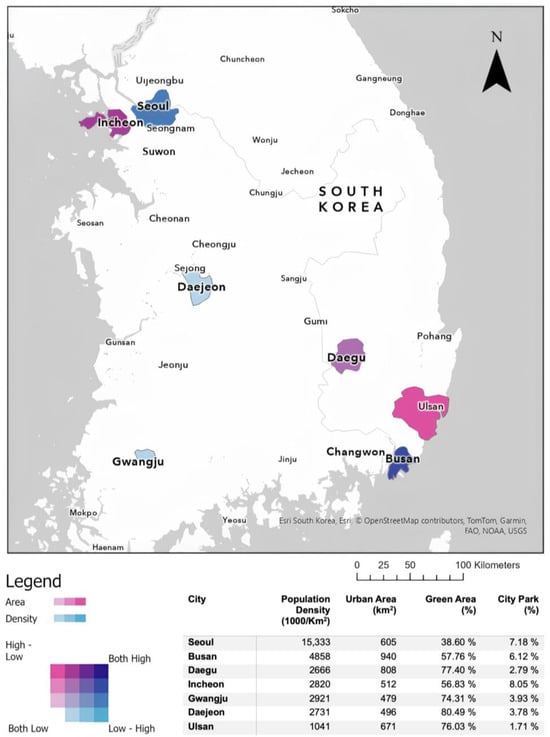

Korea comprises nine provinces and seven metropolitan cities including Seoul, Busan, Incheon, Daegu, Daejeon, Gwangju, and Ulsan (Figure 1). Among these metropolitan cities, the capital city of Seoul, with a population of 10 million and dry-winter humid continental climate (Köppen–Geiger classification: Dwa); the second-largest city of Korea, Busan, with a warm and humid climate (Köppen–Geiger classification: Cfa); and Daegu Metropolitan City, known as the hottest place in Korea with a humid subtropical climate (Köppen–Geiger classification: Cwa), were chosen as case studies due to their size, density, level of vulnerability, and varied climates.

Figure 1.

Location and characteristics of Korea’s metropolitan cities (Data source: [28,29,30]).

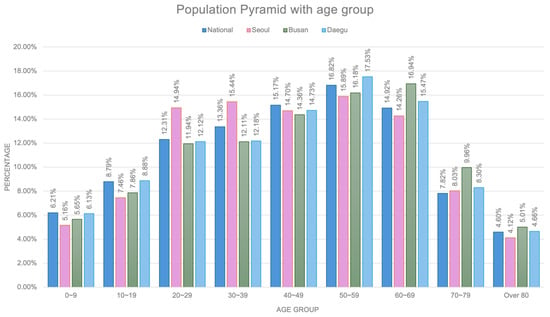

Vulnerability to increased temperatures is related to age and income [31]. As Korea is an aging society where the number of vulnerable older people is increasing (Figure 2), an adaptation policy for increasing temperatures and heatwaves is needed. According to the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency [32], a total of 1564 people had heat-related diseases in the summer of 2022 in Korea, an increase of 13.7% from last year, and the elderly aged 65 or older accounted for 27% of all patients. While the retirement age in Korea is 60 years old, the actual time of retirement depends on the job; thus, the average retirement age is 66. In the warmer case study cities of Busan and Daegu, the population aged 60 or older is significantly higher than the national average [32].

Figure 2.

Age distribution of Seoul, Busan, and Daegu compared to national averages in 2024 (Data source: [33]).

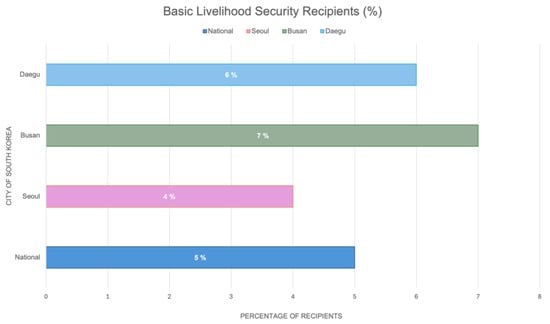

Another factor that is related to vulnerability is socioeconomic status and income. The National Basic Livelihood Security Act of Korea aims to protect fundamental human rights [34] and defines the term “basic livelihood recipient” as someone whose income falls below the standard median income, and who either lacks a supporter or has a supporter unable to provide sufficient support [35]. They are the socioeconomic class who cannot maintain the minimum lifestyle solely with their income, property, and working ability and are vulnerable. Figure 3 illustrates the percentage of basic livelihood recipients at the national level, as well as the case study cities, and shows that the percentage of recipients in Busan and Daegu are higher than the national and Seoul levels. Combined with the higher percentages of older residents, these characteristics make Busan and Daegu particularly vulnerable.

Figure 3.

Percentage of basic livelihood security program benefits recipients in Seoul, Busan, and Daegu City compared to national figures in 2024 (Data source: [33]).

4.2.1. Seoul Special City

Korea’s capital Seoul is administratively a special city. It is highly dense, housing 18 percent of the nation’s population, and is about three times larger than the second-largest city, Busan. Due to rapid urbanisation and a rapidly aging population, Seoul is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change [36]. Over the past 100 years, the average temperature of Seoul has increased by 2.3 °C from 10.7 °C to 13 °C, while the number of heatwave days has risen from 5 days per year to 18 days per year between 2005 and 2021. The Korea Meteorological Administration predicts that heatwaves will increase to 69 days per year by 2071 if greenhouse gas emissions continue at current levels [36].

Following the National Low Carbon Green Growth Framework Act, Seoul has developed detailed implementation plans for climate change adaptation every five years, the current being Detailed Implementation Plan for Climate Change Adaptation (2022–2026). The city also set a new target for climate change adaptation by 2050 in line with the Climate Action Plan (CAP) [37]. Seoul plans to prepare climate change scenarios, evaluate climate risks, and establish short, medium, and long-term goals and implementation schedules related to climate change adaptation [38]. The UHI and heatwave-related legislation exists only in three of the twenty-five districts of Seoul which include the Yangcheon-gu, Mapo-gu, Nowon-gu, and Eunpyeong-gu. Seoul Special City Regulation 2022 does not include a comprehensive regulation for heatwave damage prevention and response. The Seoul Metropolitan City Climate Action Plan 2050 envisions Seoul becoming a low-carbon climate-safe city, and its objective is healthy and safe cities by boosting climate change adaptation capabilities.

Seoul Climate Action Plan includes the following strategies: green remodeling of old buildings, speeding up the supply of sustainable cars, expanding urban forests, building heat evacuation facilities and safety systems, intensifying monitoring, and expanding urban green areas. Currently, Seoul is raising funds through the Regulation on the Establishment and Operation of the Climate Change Fund, financed from various sources such as general account contributions, fund operations revenue, and dividends from entities like the Korea District Heating Corporation. In 2021, Seoul established its own climate budget classification system and piloted a climate budget statement in 2022 across three departments. By 2023, the climate budget system was fully implemented across all city departments [39]. Outside sources may include central government support and corporate and civil society funding, while internal funding can be secured through climate policy budgets. In addition, the city’s policies include green infrastructures such as planting street trees, implementing green roofs, green façades, urban agriculture revitalization, etc. The Seoul Metropolitan Government Regulation on Support for the Green Roof was enacted in 2019. Table 3 provides an overview of Seoul Special City’s relevant laws and regulations related to UHI effect mitigation and heatwave adaptation.

Table 3.

Heat adaptation measures found in Seoul Special City policies.

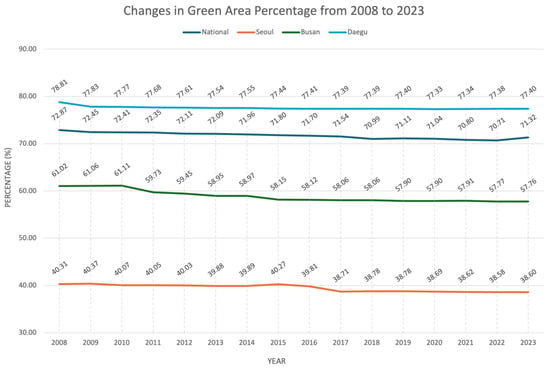

Green areas have been steadily decreasing in all three case study cities and nationally since 2008 (Figure 4). Seoul has the smallest green area among the three cities and the heat island effect is higher than that of comparable cities [40]. There is a slight increase in urban parks. In 2020, the total urban park area was 42,365 m2, growing to 43,468 m2 by 2023. A study on the history of Seoul’s parks and greenspace policies found that in parallel with increasing urbanization in South Korea the parks and greenspace policy has focused on quantitative expansion from 1960 to the mid-1990s [41]. However, after moving to a system of popularly elected mayors in 1995 urban greenspace policies in Seoul have moved from quantitative expansion to qualitative improvement and an increase of greenspaces around residential areas.

Figure 4.

Change of green area percentage in Seoul, Busan, and Daegu compared to national figures from 2008 to 2023 [29].

Seoul’s most ambitious green infrastructure strategy is the 30 million tree-planting project to cope with the impacts of the city’s deteriorated climate environment, such as heatwaves and fine dust. The project was introduced in 2014 and aimed to plant 30 million trees by 2022, and it successfully exceeded this goal, with a total of 31,284,436 trees planted. An analysis shows that 30 million additional trees will reduce fine dust emitted by 64,000 old diesel cars a year and lower the city’s temperature by equivalent to operating 24 million air conditioners for 5 hours [42]. The Urban Park Protection Campaign of 2013, Seoul’s urban greening campaign, is a civic-led urban greening campaign that supports citizens to plant and grow flowers and trees in their daily living spaces to expand greenspaces. Seoul has protected most of its areas designated under the ‘Urban Park Expiration System’ by compensating landowners and ensuring these areas are developed into functional parks to prevent removal of the designation and loss of the function of urban parks if the park was not built or developed for 20 years after it was designated. A study by Hwang, et al. [43] examining change in vegetated areas in Seoul over a 32-year period (1987–2018) found significant greening in approximately 39 percent of the city. The main driver of this greening is suggested to be an expansion of vegetation due to planting trees along streets and in residential areas and creating urban parks. On the other hand, a 7 percent browning trend was observed in the city due to the conversion of vegetated areas to impervious surfaces. At the city scale, a greening trend at a rate of 0.002 yr−1 was observed. This is important because a trend of lower heat-mortality associations is observed in areas of higher urban vegetation in Seoul while higher heat-mortality associations are observed particularly in women and people aged over 65 in areas of lower levels of urban vegetation [44]. Furthermore, a study examining the effectiveness of extreme heat adaptation strategies in Seoul found that green walls, sidewalk greenways, and reduced-albedo sidewalks were only effective under low-emission scenarios. Only street trees were found to be effective in reducing the extreme heat impacts under high-emission scenarios [45].

After the first pilot operation in Seoul in 2006, the world’s first clean road system was installed on Sejong Road in front of Gwanghwamun Gate and Olympic Road in front of Jamsil Sports Complex in 2008, covering a length of 500 m on each road. The system sprays pure underground water onto the road surface through a spray nozzle. This improves the air quality of the road by allowing water to flow on the road surface to wash away fine dust and tire dust particles, which reduces the UHI effect. In addition, a pilot operation of a cooling fog system which is a cooling device that absorbs latent heat while vaporizing by spraying water at high pressure was promoted to relieve heat island effects. To accelerate the supply of eco-friendly cars, the Seoul Metropolitan Government has replaced them with electric or hydrogen buses when replacing city buses. From 2025, they are required to purchase only electric or hydrogen cars. By 2026, the Seoul Metropolitan Government will supply 400,000 electric vehicles to lead the 10% electric vehicle era. From 2030, this will also be mandatory for taxi replacement.

To improve the ability of the vulnerable groups to adapt to heatwaves the Regulation on Heatwave Prevention and Damage Support states that Seoul shall actively protect low-income people and elderly living alone who do not have cooling facilities. In addition, Seoul supported 3589 senior cooling centres as special protection was needed as the incidence of heat-related diseases could increase for the elderly with weak adaptability to climate change [40]. Measures to protect the homeless on the streets in the event of a heatwave are also promoted. In addition, a heatwave forecast/alarm system and a monitoring system have been established in 2012. The risk of thermal diseases increases due to heat fatigue of construction workers and measures to protect workers were strengthened to improve the ability of construction sites vulnerable to heatwaves to adapt [40]. A cooling centre is operated to avoid heat and heatwave alarms, and visiting health care workers are also used to prepare the vulnerable for the heatwave. In preparation for the heatwave, behavioural tips for citizens and manuals for sites vulnerable to the heatwave were activated. To strengthen citizens’ ability to adapt to the heatwave, the government has established an emergency contact network between the responsible departments to spread the information and respond to the situation when heatwave warnings/alerts are issued. The second Seoul Metropolitan Government Adaptation Plan includes maintaining a break time of 15 min every hour or suspending work under the judgment of the site manager when a heatwave warning is issued, as well as installing, cooling facilities in the lounge and installing shade screens at the construction site. Among the three case study cities, only Seoul does not have a cool roof project. Although the Korean Government supports cool roof projects at the national level, the 69 detailed climate change adaptation projects outlined in the 2nd Comprehensive Plan for Climate Change Response in Seoul (2017–2021) include green roofs and green walls but do not feature cool roof projects.

In November 2023, Seoul announced its commitment to pursue climate change adaptation measures to minimize the impact of heatwaves on citizens [36]. The measures being implemented include: (1) Providing cooling appliances such as fans, health supplements, cool scarves, etc., to 16,000 vulnerable households, and offering emergency cooling assistance to 1000 households, including energy cost support; (2) Expanding road cleaning efforts to mitigate the UHI effect, including increasing water spraying on roads during heatwaves; (3) Adjusting working hours for outdoor workers during heatwaves to ensure their safety, including special leave provisions and cool facilities in rest area; (4) Conducting special inspections for ozone alerts and Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) emissions from industrial facilities, aiming to reduce harmful emissions and protect public health; (5) Organising a fashion show to promote cool and comfortable attire during hot weather, with sustainable materials such as recycled PET fabrics and upcycled clothing to reduce climate impact. In June 2024, Seoul Metropolitan Government [46] announced that the Seoul Social Welfare Council had supported approximately 460,000 vulnerable households from 2015 to 2023 through donations. Due to the increasing frequency of heatwaves, the support provided has been raised by 64% from around 500 million KRW in 2023 to 840 million KRW in 2024.

Seoul Special City’s policies are focused on the expansion of green infrastructure and targeted strategies for vulnerable people. While green and blue infrastructure is actively implemented, challenges remain with gray infrastructure, as cool roof projects have not yet been included in the city’s plans. Overall, while there are some adaptation efforts they are not sufficient.

4.2.2. Busan Metropolitan City

Busan Metropolitan City, located in the southeastern part of Korea, has a total population of 3,331,444 and contains 6% of Korea’s population. It is the second-largest city in Korea and has the second-highest population density after Seoul. Busan is Korea’s largest port city housing the largest international trade port and is greatly influenced by the ocean due to its location, resulting in a characteristic marine climate that does not have a significant temperature difference between summer and winter. According to the average annual temperature over the past 50 years, Busan’s daily maximum and minimum temperatures are continuously rising, and the number of heatwave days is also steadily increasing. The number of older people vulnerable to heat increased by 6.1% compared to 10 years ago. Busan has a high proportion of the elderly population compared to the national average and this is expected to increase [47].

From May 2020, the Busan Metropolitan City implemented a regulation that prescribes matters necessary to prevent heatwave damage and alleviate the UHI phenomenon to ensure the health and safety of citizens by responding to heatwaves. In 2021, the Dongnae-gu District of Busan Metropolitan City enacted the Regulation on the Prevention and Response to Heatwave Damage. Busan established comprehensive measures and implementation plans to cope with heatwaves. The third Busan Metropolitan City Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2022–2026) (hereafter Busan Climate Change Adaptation Plan) Detailed Implementation Plan outlined strategies to address heatwaves and UHI in the health sector on page 562. The major strategy is protecting vulnerable groups who are at high risk due to climate change. The plan aims to minimise the health risks associated with extreme weather by developing a supportive environment for vulnerable people. Key initiatives include managing heatwave impacts through measures like cool roof systems and the UHI integrated management system [47]. This plan aims to expand support for vulnerable groups exposed to heatwaves, with an expected reduction in the occurrence of heat-related diseases through the establishment of the support system.

Busan Climate Change Adaptation Plan: Detailed Implementation Plan (p. 481) indicates that heat-related diseases occur yearly in Korea, with the highest incidence among people aged 65 or older. In the past five years (2016–2020), Busan recorded seven deaths due to heatwaves, the fourth highest in Korea [47]. Expert risk assessment of the national climate change risks in the health sector showed that Busan was the most vulnerable to an increase in thermal diseases due to heatwaves. Busan announced comprehensive measures to prevent and respond to heatwave damage in 2008 in anticipation of an increase in the average temperature in summer and the frequency and intensity of heatwave days due to climate change. The basic policy was to strengthen the heatwave-related systems, promote protection measures for the vulnerable, and promote public action against heatwaves. The main initiatives of Busan City include the operation of cooling centres, heat breaks, helpers for the vulnerable in preparation for heatwaves, heatwave special emergency teams, and support for temporary residential facilities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Heat adaptation measures found in Busan Metropolitan City policies.

Busan developed and implemented urban forest creation, development, and expansion strategies to protect water resources. For example, Busan implemented a forest managing project and stated urban forest creation has a significant effect on mitigating UHI and reducing temperature by 3 °C to 7 °C [47]. Busan established a global ecological network, which helped improve the tree growth environment. Busan is promoting a green tourism city. It is implementing various strategies for the green city, such as reorganizing parks, promoting the designation of national parks, and developing the forested Busan Green Line Park under the elevated railroad tracks [48]. The Busan Metropolitan City created a wind path to alleviate the heat island effect, a management strategy to maintain the cold air generated in the mountain flowing smoothly to nearby cities through the creation of cold air and flow analysis of the mountain. Busan has been implementing cooling centres and cool roof projects for vulnerable households to alleviate the heat island effect in industrial areas since 2016. Since 2004, the renewable energy housing support project has been in operation and solar panels have been installed. Busan has also established a response system for heatwave situation management. A management and support system was established for the heatwave vulnerable groups. The Busan Climate Change Adaptation Plan identifies these groups as follows:

- Persons with disabilities under Article 2 (1) of the Welfare of Persons with Disabilities Act

- Beneficiaries under subparagraph 2 of Article 2 of the National Basic Living Security Act

- An elderly person living alone under subparagraph 1 of Article 2 of the Busan Metropolitan City regulations on the Support of Joint Residential Facilities for the Elderly Living Alone

- A person who is deemed to need preferential support, such as a child-headed household (a household in which a child under the age of 18 is the head, under the National Basic Livelihood Security Act [49]), single-parent families, etc.

- Any other person who the Mayor of Busan Metropolitan City deems vulnerable to heatwaves, such as outdoor workers.

In addition, a heatwave warning system has been established, and epidemiological investigations are being conducted on cardiovascular disease patients greatly affected by heatwaves. The Busan Climate Change Adaptation Plan Detailed Implementation Plan includes a new action for the emergency room operating institutions to report the daily number of patients with thermal diseases. Measures to support the vulnerable will also be implemented. The expected effects are raising citizens’ awareness of climate change and minimizing damage to citizens’ health through information sharing.

Busan Metropolitan City policies include active implementation of green infrastructure such as urban forest and cooling fog systems, as well as support for vulnerable people. While efforts are being made, the city does not have a comprehensive heatwave policy. The lack of such a policy is limiting adaptation progress. In addition, targets in infrastructure are very modest compared to the population size and need.

4.2.3. Daegu Metropolitan City

Daegu Metropolitan City has the fourth-largest population in Korea after Seoul, Busan, and Incheon, housing 5% of Korea’s population. Among Korea’s 75 cities, Daegu has experienced the most heatwaves [50] due to its geographical and climatic characteristics including high climate exposure and low adaptability. Daegu set an example for active administration with the nation’s first non-statutory heatwave response plan. Daegu City announced the Daegu Metropolitan City Heatwave and Urban Heat Island Response Regulation, which aims to improve citizens’ welfare by responding to the heatwaves caused by global warming and reducing the UHI phenomenon caused by urbanization. Additional related legislation includes the Daegu Regulation on Supporting the Creation of Green Buildings.

Daegu Metropolitan City enacted a regulation in 2018 in response to higher level laws that included heatwaves among natural disasters, supporting the vulnerable groups and installing and maintaining heatwave reduction facilities (Table 5) [25]. The main contents of this regulation include support for heatwave relief facilities such as cool roofs to overcome the summer heat. However, these are expensive projects, and investment in them is still limited. There are 5699 public and 205,100 private buildings in Daegu [51]. There is no record of cool roofs in the city pre-2017. The number of cool roofs installed since 2017 through this support makes up only 1.19% of public buildings and 0.05% of private buildings in the city.

Table 5.

Heat adaptation measures found in Daegu Metropolitan City policies.

The basic plan for heatwaves and the UHI effect in Daegu is established and implemented every five years and comprehensive measures to cope with the UHI are established every year. The vision of the Daegu Metropolitan City Heatwave and Urban Heat Island Effect Basic Response Plan (2020) is “turning heatwaves into a resource with the community”. The objectives include increasing citizen satisfaction, reducing summer heat, helping and sharing tasks, and adding cool industries to the local economy. The four main strategies include comprehensive heatwave response with no blind spots, more effective heatwave mitigation, long-term heatwave preparation, and activities that help the local community [52].

Another UHI-related plan is the 2030 Daegu Metropolitan City Parks and Greenspace Master Plan (2017). The composition of the basic plan for Daegu’s heat island adaptation measures consists of vision, goals, strategies, indicators, and tasks. As a heatwave policy, Daegu City has established five strategies, and five tasks are identified for each strategy: (1) Air quality improvement: securing thermal environment observation equipment, implementation of a 2-day vehicle system in case of the heatwave, creating a ventilation path, renewable energy activation, and electric vehicle supply; (2) Creating a cool environment: creating a pocket park, river restoration, roadside greenspace, expansion of the school forest project, and green roof support; (3) Expansion of eco-friendly buildings: cool roof support, reorganization of old buildings, green façade, maintenance of cooling centres, and encouraging thermal sensitive finishing materials for rental housing; (4) Surface management: clean road implementation, concrete board block replacement, shade canopy installation, increase the number of shade trees, and water circulation city with low impact development (LID); (5) Creating a community: heatwave promotion and educational activities, care services for the elderly people, rural area management, establishment of a thermal patient monitoring system, and civil capacity enhancement.

Rivers play an important role in blue and green infrastructure and in lowering the urban temperature by forming an evaporation effect and a wind path. Daegu City implemented a river restoration strategy to improve the thermal environment to restore the lost rivers. This includes investigating rivers that can be restored and finding sustainable river directions. The Daegu official website divides forest and green area promotion policies into three categories: the creation of urban forests, the civic participation urban greening movement, and the creation and management of street trees [53]. It consists of seven measures, including creating a wind path forest that brings the cold wind of forests to the city centre, creating a forest recreation park, and creating an urban forest representing Daegu. The goal of Daegu’s urban greening policy has been promoting the “Create Green Daegu” project that started in 1996. The first project, which lasted for 11 years from 1996 to 2006, planted a total of 10.93 million trees. The second project was completed in five years from 2007 to 2011 and added another 12.08 million trees, raising the green area rate of the city by 2.5%. The third project planted 11.64 million more trees over five years, and the fourth project added 12.6 million trees over five years. The fifth project, which will be carried out for five years from 2022 to 2026 aims to plant 12.75 million trees [54].

In addition, the Urban Wind Corridor Forests project implemented from 2023 to 2025 introduces clean, cool air from forests into the city to mitigate the UHI phenomenon and heatwaves. Greening rooftops project resulted in the establishment of green roofs in 87 public sector buildings (33,641 m2) and 1033 private sector buildings (164,659 m2) to reduce the heat island effect by 2023 [55]. However, like cool roofs, this makes up only a fraction of the total buildings in Daegu (1.53% of public buildings and 0.5% of private buildings). There are street tree policies to create a green street environment by planting street trees on newly opened roads and tree maintenance. This policy includes creating a luxury street forest road that can enhance the city brand by making Dalgubeol Road Daegu’s representative street and street tree management to improve the street environment. As of 31 December, 2023, Daegu had 239,394 street trees [56].

Daegu is vulnerable to water circulation due to its highly impermeable concrete and asphalt surfaces that cannot absorb rainwater. Daegu developed a water circulation strategy based on the Low Impact Development (LID) approach. The aim is to restore the natural water circulation function and convert Daegu into a water circulation city with excellent adaptability to the heat island effect. This strategy includes securing the water permeability of pavement areas in downtown Daegu, replacing the existing parking lots with sustainable pavement, and preparing new pavement guidelines. In addition, various blue infrastructures, such as pavement watering and clean road systems, cooling fogs, and wall fountains are being implemented on significant highways. Daegu Metropolitan City Heatwave and Urban Heat Island Effect Basic Response Plan (2020) identifies heatwave vulnerable groups as:

- Persons with disabilities under Article 2 (1) of the Welfare of Persons with Disabilities Act

- A person who is deemed to need preferential support, such as a child head of household, a single-parent family, an elderly single person, a pregnant woman, etc.

- Beneficiaries under subparagraph 2 of Article 2 of the National Basic Living Security Act

- Any other person deemed necessary by the Mayor of Daegu Metropolitan City

In the comprehensive measures against heatwaves in 2017, Daegu provided education and promotion for the elderly and particularly the elderly living alone. It focused on the caregivers of the elderly who were trained in emergency measures in response to heatwaves in areas where the elderly living alone are concentrated. Five out of six deaths from heat-related diseases in Daegu are people aged 80 or older in farming areas. Rural readjustment was implemented to prepare systematic measures for heatwave response in rural areas. To manage heatwaves in rural areas a monitoring centre is established and a community space where rural residents gather is created. This has the additional benefit of reducing social isolation. A special monitoring team was established to operate a thermal patient monitoring system that can systematically and immediately respond to thermal patients. Heatwave educational activities were conducted to strengthen citizens’ capabilities.

Daegu Metropolitan City has comprehensive and detailed heat policies, setting a strong example for other cities through active policies. Daegu focuses on green and blue infrastructure and targeted support for vulnerable people with grey infrastructure.

4.3. Adaptation Progress

This review found that there is no systematic basis for mainstreaming climate change adaptation in Korea. Current planning regulations that address climate change are general. General climate change measures established yearly do not deviate significantly from the existing scope and their practical ability is limited due to the lack of enforceability through laws. In addition, many projects are short term, about 2–3 years [52]. First, policies should be much more detailed and specific with measurable targets and dates. There are also impediments to implementation. Ten years have passed since introducing the national climate change adaptation policy, but citizens’ awareness of climate change adaptation is still only at around 60%, and implementation is challenging. For example, there is a limit to creating protected ecosystem areas due to the difficulty of designating a protected area if the landowner opposes it. There is limited compulsory execution of projects related to the homeless and those whose health is vulnerable to heatwaves through human rights protection. Current national heatwave responses involve inter-agency cooperation to share awareness of issues and seek joint response strategies, but in practice, projects are fragmented across ministries limiting the creation and establishment of long-term heatwave measures [6]. Local government responses to heatwave-related projects are mainly focused on the health impacts on vulnerable groups, such as the elderly and single-person households, and are found to be insufficient in addressing the broader UHI challenges [6]. Systematic cooperation between departments administering related areas such as cities, the environment, architecture, and health should be further strengthened. It is necessary to promote statistical analysis, investigations, and in-depth research on victims of thermal diseases. It is also essential to improve the heatwave warning systems [52].

5. Discussion

5.1. Urgency Results in Action

Comparing the heatwave and heat island policies of the three cities in Korea shows that Daegu Metropolitan City is ahead of other regions. Since the impact of climate change varies depending on each region’s geography or coping ability, the damage caused by climate change occurs differently in each city. Daegu is known to be particularly hot in Korea and is nicknamed Daefrica (Daegu + Africa) [57]. This is due to its geographic characteristics and topography surrounded by mountains that prevent the wind from crossing the mountain. As a result, Daegu is leading the heatwave policy and research by turning the risk of heatwaves into an opportunity. According to data from the KMA, Daegu faced the first heatwave in Korea during 2021 [26] and the most extended heatwave lasted 11 days in 2020 [58]. The total number of annual heatwave days in Korea in 2020 was 7.7, and the heatwave in Daegu was about three days longer than the average. Daegu has the highest proportion of vulnerable groups at risk of a heatwave among the cities examined followed by Busan and Seoul. However, as heatwaves can pose a risk to populations of all ages, the response to heatwaves and policies need to be expanded to include all age groups. The most active city in responding to the heat impacts of climate change is Daegu, which started planting trees 15 years ago. Daegu has a long list of blue infrastructure policies, such as river restoration, cooling fog, etc., compared to other cities.

Daegu has already considered heatwave and UHI issues in various plans. Unlike other cities, Daegu’s basic plan for responding to heatwaves and UHI phenomenon specifically separates strategies for responding to urban heat islands. This clearly shows which parts of the plan are directly focused on urban heat islands. The preparation of measures for Daegu’s UHI mitigation efforts focused only on the heatwave and UHI, avoiding overlap with other strategies such as performance metrics, goal implementation, and citizen awareness. The improvement of urban fabric to reduce urban heat islands was partially covered in the Parks and Greenspace Master Plan and the Landscape Plan, and the connection of spaces such as wind roads through the green-blue network in the Parks and Greenspace Master Plan. Commonly presented various greening projects related to the green infrastructure in the Environmental Conservation Plan and the Park Greening Plan, and measures to reduce heatwave damage are covered in the Safety Management Plan. A new strategy is needed to prevent issues such as confusion or duplicated investment among these related plans addressing heatwaves. Daegu has a mid-to-long-term plan to respond to heatwaves, and the plan’s goal is to reduce the annual average number of tropical nights (defined as a day with a daily minimum temperature exceeding 25 °C [59] by 30% by 2027. This strategy includes preparing a legal system to promote heatwave countermeasures, building heat reduction, improving road pavement, expanding mitigation facilities, and urban greening. Funds for most of the plans, such as clean roads, green roofs, improvement of old houses for the vulnerable, and expansion of cool roof projects, were provided by central ministries, local funds, and private funds. Daegu established the nation’s first non-statutory heatwave response plan, setting an example through active administration and helping to develop a foundation for heatwave response.

Seoul has the highest population density; however, unlike Busan and Daegu, it has not implemented its own regulations to prevent and respond to the heatwaves. Seoul has implemented many large projects, such as tree planting and urban forest expansion. The Seoul Research Institute has studied park temperature and urban heat islands. Seoul also has a better policy on sustainable cars than other regions and is implementing sustainable car subsidies to supply 400,000 electric vehicles by 2026. In addition, the Seoul Metropolitan Government is receiving applications for the installation of electric vehicle charging stations based on user demand for the smooth supply of sustainable vehicles. Heatwave measures for the vulnerable in the three cities are well-established, but Seoul’s policy has the most extended list. In addition, unlike other cities, Seoul promotes measures to protect the homeless during heatwaves.

Busan has cool roof and urban wind corridor projects. Busan has never established a comprehensive heatwave policy before, and it was integrated into general climate change policy after research on urban heat islands in the 2000s.

5.2. Bluegreen Infrastructure Is Popular

Consistent with the findings of the literature review, green and blue infrastructure are the most common strategies against heatwaves in Korea, and among these vegetation and greening strategies are the most popular. This is not surprising considering how effective this strategy is. For example, an econometric analysis of UHI mitigation with urban forests in Korean cities found that 1 m2 per person increase in urban forests decreases the summer daytime temperature for metropolitan cities by 1.15 °C [60]. Green building envelopes seem to be scant. Whereas grey infrastructure was the second most mentioned strategy in the literature there was little mention of it in the Korean policies examined except for the cool roof support strategy in Daegu and Busan and cool pavement for urban roads in Daegu. Instead, contrary to the literature review, all three cities had many behavioural strategies for inhabitants, such as protecting vulnerable groups, early warning systems, and medical alerts. In a Busan citizen’s survey, the health sector emerged as the top priority, receiving the highest response rate of 16% among areas to be prioritized when establishing climate change adaptation measures [61]. Additionally, the Busan impact assessment revealed that 27% of respondents, both in the citizen survey and government evaluations, indicated that projects supporting vulnerable populations should be prioritized.

5.3. Fragmented Responsibility Results in Fragmented Action

Despite the serious impacts of UHI in the densely populated Korean cities and the increasing vulnerability of their population, policies and strategies that directly target the impacts of rising temperatures are limited. While there are strategies that can help with heatwaves and UHI in general climate adaptation policies or projects, these are not explicitly linked to climate adaptation. Their main aim may be sustainable transport or some urban greening programs that target, for example, water quality. Response to heatwaves is a co-benefit. As it is not part of the aim, opportunities to maximize the cooling benefits may be missed.

The key informant interview confirmed the overall findings of the policy review. Heat island-related responsibilities and policies are scattered across several ministries, including the Ministry of Environment, Construction and Transportation, Korea Forest Service, etc. Most of Korea’s heatwave policies protect the weak by providing shelter and cooling centres for vulnerable groups. Each ministry and local government in Korea established measures to adapt to climate change. While this is as it should be, better coordination is necessary for effective outcomes.

5.4. Transformative Approaches Are Scant

While there seems to be some action towards adaptation to heatwaves in major cities in Korea the policy review findings indicate that most of those focus on coping or incremental approaches. There is limited evidence of transformation. This is consistent with findings of research that examine other impacts of climate change in other countries as well. For example, a review of adaptation strategies for climate change impacts on water quality [62] found that most strategies identified fall into low resilience coping or incremental approaches with very few transformational high resilience approaches. Research on adaptation to climate-related disasters in two coastal Australian cities found very limited evidence of transformational adaptation with current policy and practice focusing mainly on preserving existing ways of life through coping and incremental strategies and a short-term focus [18,63]. Similarly, a review of coastal policy in Australia also found heavy reliance on coping and incremental strategies such as protection and accommodation rather than transformational adaptation options such as managed retreat [64].

Transformational approaches require the integration of resilience principles such as redundancy, diversity, safe failure, etc. which impose higher initial development and planning costs [18]. Torabi, et al. [65] found that political resilience and leadership are crucial for going beyond a bounce-back mentality of maintaining existing ways of life with the sole focus on reducing the consequence of hazards and achieving a transformative and evolutionary approach to resilience. The political support for this kind of transformation usually comes after big crises events. For example, the Millenium Drought experienced in southern Australia between 1996 and 2010 resulted in major transformational infrastructure investments and institutional restructuring [66].

6. Conclusions

This paper presented the findings of a review of Korea’s adaptation strategies and policies at the national level as well as for three selected metropolitan areas for heatwaves and heat island effect. The main findings are:

- Of the three cities studied, which include Korea’s largest and second- and fourth-largest cities, Daegu has the most comprehensive and detailed heat policies, due in part to its higher levels of physical (hottest large Korean city) and social (highest proportion of vulnerable residents) vulnerability.

- There are limited policies and strategies in place that directly target the impacts of rising temperatures despite UHI being a serious issue in densely populated Asian cities. The commitment to expensive infrastructure such as green roofs and cool roofs so far has been far short of the need.

- Most of the existing strategies focus on coping or incremental approaches to adaptation with few transformational options.

The findings show that Korea is in the early stages of policy development to adapt to the impacts of heatwaves and the UHI effect. The findings of this study are applicable to other countries with similar levels of vulnerability and urbanization patterns, particularly other densely populated Asian cities. These cities are also facing similar challenges of aging populations, fragmented action, and limited transformative approaches. Much more adaptation planning and action is needed to ensure an effective response that is comprehensive and coordinated across different agencies and jurisdictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and A.D.-H.; Formal analysis, S.A.; Investigation, S.A.; Methodology, S.A. and A.D.-H.; Supervision, A.D.-H.; Visualization, S.A.; Writing—original draft, S.A.; Writing—Review and editing, A.D.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers of this article who provided feedback on our research and suggested improvements to the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DMC | Daegu Metropolitan City |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| KACCC | Korea Adaptation Centre for Climate Change |

| KDCPA | Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency |

| KEI | Korea Environment Institute |

| KMA | Korea Meteorological Administration |

| KRW | South Korean Won |

| LID | Low-impact development |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island effect |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, Y. Adaptation measures for climate change and the urban heat island in Japan’s built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2003, 31, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Korea. The 3rd National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2021–2025); Joint Government Publication, Ministry of Environments: Republic of Korea, 2020; Available online: http://www.me.go.kr/home/web/policy_data/read.do?menuId=10262&seq=7619 (accessed on 21 October 2022). (In Korean)

- National Institute of Meteorological Sciences (NIMS). Climate Change in the Korean Peninsula: A 100-Year Overview; Publication number: 11-1360620-000132-01; National Institute of Meteorological Sciences: Seogwipo, Republic of Korea, 2018. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.; Ahn, Y. Political Effects of Countermeasures Against Heat Wave Using System Dynamics Method: Case Study in Daegu Metropolitan City. Korea Spat. Plan. Rev. 2020, 106, 41–64. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Status and Implications of Local Government Heatwave Measures; Report No. WP 22–32; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Sejong City, Republic of Korea, 2022. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Urban Adaptation to Climate Change in Europe 2016, Transforming Cities in a Changing Climate; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.L.; Jacobson, C.; Lyth, A.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Baldwin, C.L.; Ellison, J.C.; Holbrook, N.J.; Howes, M.J.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Singh-Peterson, L.; et al. Interrogating resilience: Toward a typology to improve its operationalization. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, M.J.; Luederitz, C.; Lang, D.J.; von Wehrden, H. Facing the heat: A systematic literature review exploring the transferability of solutions to cope with urban heat waves. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Icaza, L.E.; Neht, A.; Klavins, M.; Morgan, E.A. Coping with the impacts of urban heat islands. A literature based study on understanding urban heat vulnerability and the need for resilience in cities in a global climate change context. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaaitah, T.; Appleby, M.; Rosenblat, H.; Drake, J.; Joksimovic, D. The potential of Blue-Green infrastructure as a climate change adaptation strategy: A systematic literature review. Blue-Green Syst. 2021, 3, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.-D.; He, B.-J.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Fu, W.-C. Do grey infrastructures always elevate urban temperature? No, utilizing grey infrastructures to mitigate urban heat island effects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 46, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.E.; Khalili, S.; Halios, C.H.; Sahani, J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; de Fatima Andrade, M.; Athanassiadou, M.; Bhui, K.; Calvillo, N. Urban heat mitigation by green and blue infrastructure: Drivers, effectiveness, and future needs. Innovation 2024, 5, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, K.; Desouza, K.C.; Fieuw, W.; Watson, R.T.; Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding policy and technology responses in mitigating urban heat islands: A literature review and directions for future research. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturiale, L.; Scuderi, A. The role of green infrastructures in urban planning for climate change adaptation. Climate 2019, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Cui, S.; Tang, J.; Nguyen, M.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. Assessing the adaptive capacity of urban form to climate stress: A case study on an urban heat island. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 044013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulateef, M.F.; Al-Alwan, H.A. The effectiveness of urban green infrastructure in reducing surface urban heat island. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M. Adapting or maladapting: Building resilience to climate-related disasters in coastal cities. Cities 2018, 72, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sen, S.; Susca, T.; Iaria, J.; Kubilay, A.; Gunawardena, K.; Zhou, X.; Takane, Y.; Park, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Beating urban heat: Multimeasure-centric solution sets and a complementary framework for decision-making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 186, 113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, K.; Pringle, P.; Turner, B. Transformative Adaptation: What It Is, Why It Matters & What Is Needed; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Matyas, D.; Pelling, M. Positioning resilience for 2015: The role of resistance, incremental adjustment and transformation in disaster risk management policy. Disasters 2015, 39, s1–s18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation: Transformation toward sustainability in urban governance and planning. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K. Korea’s Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change. Korea Environ. Policy Bull. 2011, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Shin, J.; Song, Y.; Chang, H.; Cho, H.; Park, J.; Hong, J. The development process and significance of the 3rd National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (2021–2025) of the Republic of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daegu Metropolitan City. Ordinance on Heatwaves and Urban Heat Island Response; (No. 5189, enacted 31 December 2018); Daegu Metropolitan Government: Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2018. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Socioeconomic effects of meteorological advisories. Meteorol. Technol. Policy 2022, 15, 7. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Ahn, Y. Results of the 2022 heat-related illness surveillance. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2023, 16, 241–252. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. Population and Population Density by Region. Available online: https://www.index.go.kr/unity/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1007 (accessed on 8 August 2024). (In Korean)

- Statistics Korea. Green Space Rate (City/City/County/District). Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1YL202105E&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 14 February 2025). (In Korean)

- Statistics Korea. Urban Park Area per 1,000 People (City/Province). Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?%3F%3Fconn_path%3DD9%26tblId%3DDT_1YL21281%26vw_cd%3DMT_GTITLE01%26orgId%3D101%26%3D%26 (accessed on 14 February 2025). (In Korean)

- Kim, Y.; Joh, S. A vulnerability study of the low-income elderly in the context of high temperature and mortality in Seoul, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 371, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Report Status of Thermal Disease Emergency Room Monitoring System in 2022. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a20308040107 (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Korean)

- Statistics Korea. Population Census. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1IN1503&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 8 August 2024). (In Korean)

- Jung, I. Explaining the Development and Adoption of Social Policy in Korea: The Case of the National Basic Livelihood Security Act. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2009, 29, 52–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Criteria for Selecting Recipients. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/menu.es?mid=a10708010300 (accessed on 8 August 2024). (In Korean)

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Climate Crisis Response Heatwave Measures… Lowering Urban Temperatures and Supporting Vulnerable Groups. Available online: https://news.seoul.go.kr/env/archives/518869 (accessed on 8 January 2025). (In Korean)

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2050 Seoul Climate Action Plan; Climate and Environment Serial No. 411-0021; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Seoul. Special City Climate Response Plan 2050; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, J. Seoul’s Climate Budget System: Current Status and Improvement Directions; Policy Report No. 371; The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Comprehensive Measures for Summer Heatwave 2022. Available online: https://opengov.seoul.go.kr/sanction/26010997?from=mayor (accessed on 2 November 2024). (In Korean)

- Choi, J.; Kim, G. History of Seoul’s Parks and Green Space Policies: Focusing on Policy Changes in Urban Development. Land 2022, 11, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Tree Planting Project. Available online: https://news.seoul.go.kr/env/square/tree_planting_project (accessed on 14 October 2022). (In Korean)

- Hwang, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Qu, S. Expanding vegetated areas by human activities and strengthening vegetation growth concurrently explain the greening of Seoul. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 227, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.-Y.; Lane, K.J.; Lee, J.-T.; Bell, M.L. Urban vegetation and heat-related mortality in Seoul, Korea. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Lee, D.K.; Hyun, J.H. The effects of extreme heat adaptation strategies under different climate change mitigation scenarios in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Preparing for Heatwaves… Providing Cooling Supplies for Vulnerable Households. Available online: https://news.seoul.go.kr/env/archives/558574?listPage=1&s= (accessed on 14 February 2025). (In Korean)

- Busan Metropolitan City. 3rd Busan Metropolitan City Detailed Implementation Plan for Climate Change Adaptation 2022–2026; Government Publications Registration No. 52-6260000-000407-23; Busan Metropolitan Government: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. (In Korean)

- Busan Metropolitan City. Green City Busan Metropolitan City. Available online: https://www.busan.go.kr/depart/ahgreencity (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Korean)

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Support for Child-Headed Households. Available online: https://www.gov.kr/portal/service/serviceInfo/135200000006 (accessed on 9 January 2025). (In Korean)

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, B. The occurrence characteristic and future prospect of extreme heat and tropical night in Daegu and Jeju. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2015, 24, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport. Building Statistics: Building Status by Ownership Classification. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=116&tblId=DT_MLTM_560&conn_path=I2 (accessed on 17 February 2025). (In Korean)

- Daegu Metropolitan City. Daegu Metropolitan City Heatwave and Urban Heat Island Effect Basic Response Plan (2020); Daegu Metropolitan Government: Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2020. (In Korean)

- Daegu Metropolitan City. Forest and Green Space. Available online: https://www.daegu.go.kr/index.do (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Korean)

- Daegu Metropolitan City Forestry and Greenery Division. Greening Daegu. Available online: https://www.daegu.go.kr/env/index.do?menu_id=00001241 (accessed on 8 January 2025). (In Korean)

- Daegu Metropolitan City Forestry and Greenery Division. Creating an Urban Forest. Available online: https://www.daegu.go.kr/env/index.do?menu_id=00001246 (accessed on 8 January 2025). (In Korean)

- Daegu Metropolitan City Forestry and Greenery Division. Construction and Management of Street Trees. Available online: https://www.daegu.go.kr/env/index.do?menu_id=00001248 (accessed on 8 January 2025). (In Korean)

- Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Moon, H. A Study on Daegu City Citizen’s Consciousness about Urban Green Space for Heat Wave Mitigation. J. Recreat. Landsc. 2018, 12, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Heatwave Date Data. Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr/climate/heatWave/selectHeatWaveChart.do (accessed on 10 October 2022). (In Korean)

- Park, W.; Suh, M. Characteristics and Trends of Tropical Night Occurrence in South Korea for Recent 50 Years (1958–2007). Atmosphere 2011, 21, 361–371. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, E.-G.; Yang, J.-S.; Kim, H.-G.; Shin, H.-J. An econometric analysis of mitigating urban heat island effect with urban forest. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2011, 100, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Busan Metropolitan City. Ordinance on the Prevention of Heatwave and Mitigation of Urban Heat Island Effect; (No. 6128, Enacted 27 May 2020); Busan Metropolitan Government: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2020. (In Korean)

- Bartlett, J.A.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A. Adaptation strategies for climate change impacts on water quality: A systematic review of the literature. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 651–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M. Not waving, drowning: Can local government policies on climate change adaptation and disaster resilience make a difference? Urban Policy Res. 2017, 35, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Torabi, E.; Howes, M. Planning for a different kind of sea change: Lessons from Australia for sea level rise and coastal flooding. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M. A framework for using the concept of urban resilience in responding to climate-related disasters. Urban Res. Pract. 2022, 15, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.A.; Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A. Responding to change: Lessons from water management for metropolitan governance. Aust. Plan. 2020, 56, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).