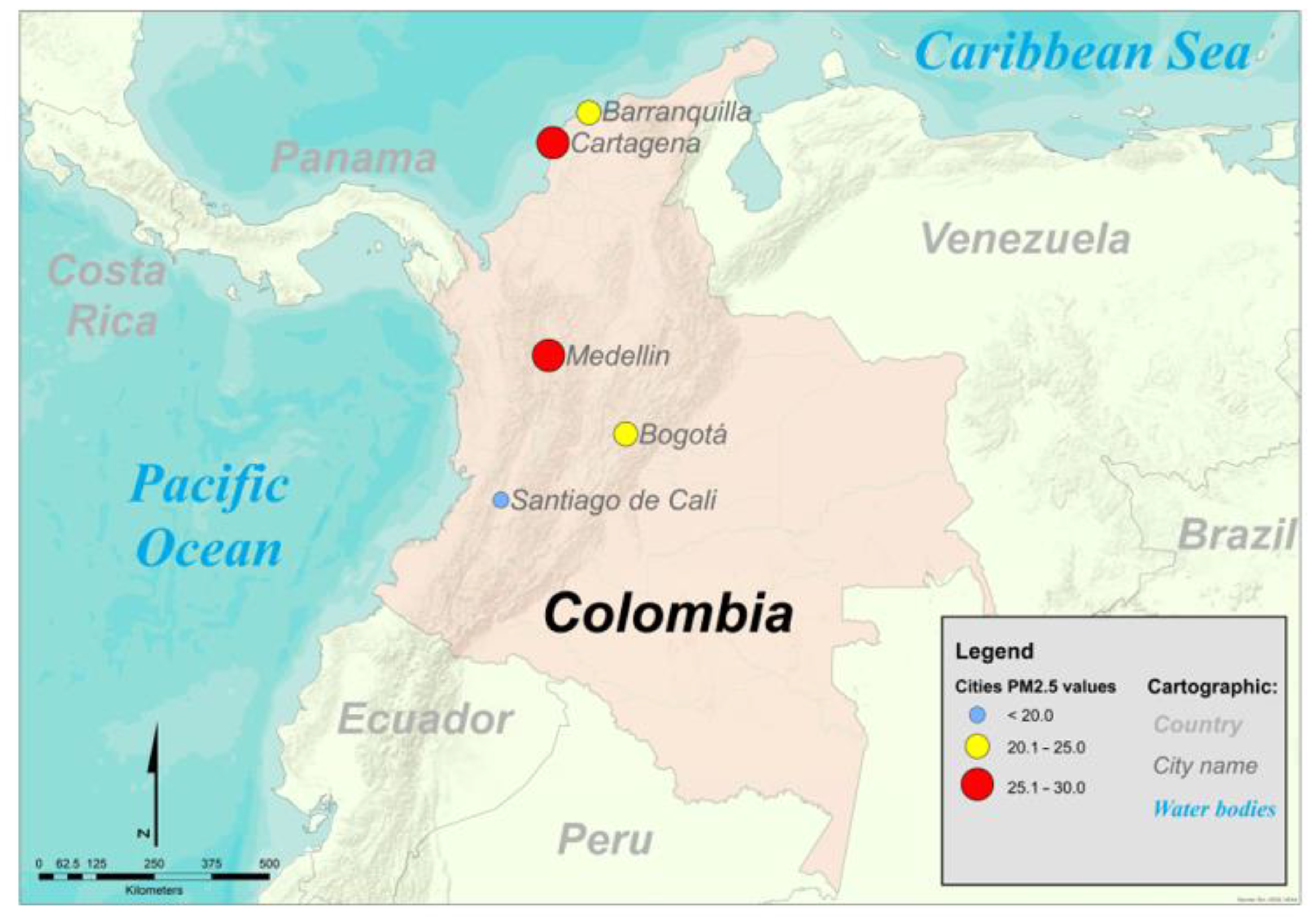

Environmental and Health Benefits Assessment of Reducing PM2.5 Concentrations in Urban Areas in Developing Countries: Case Study Cartagena de Indias

Abstract

1. Introduction

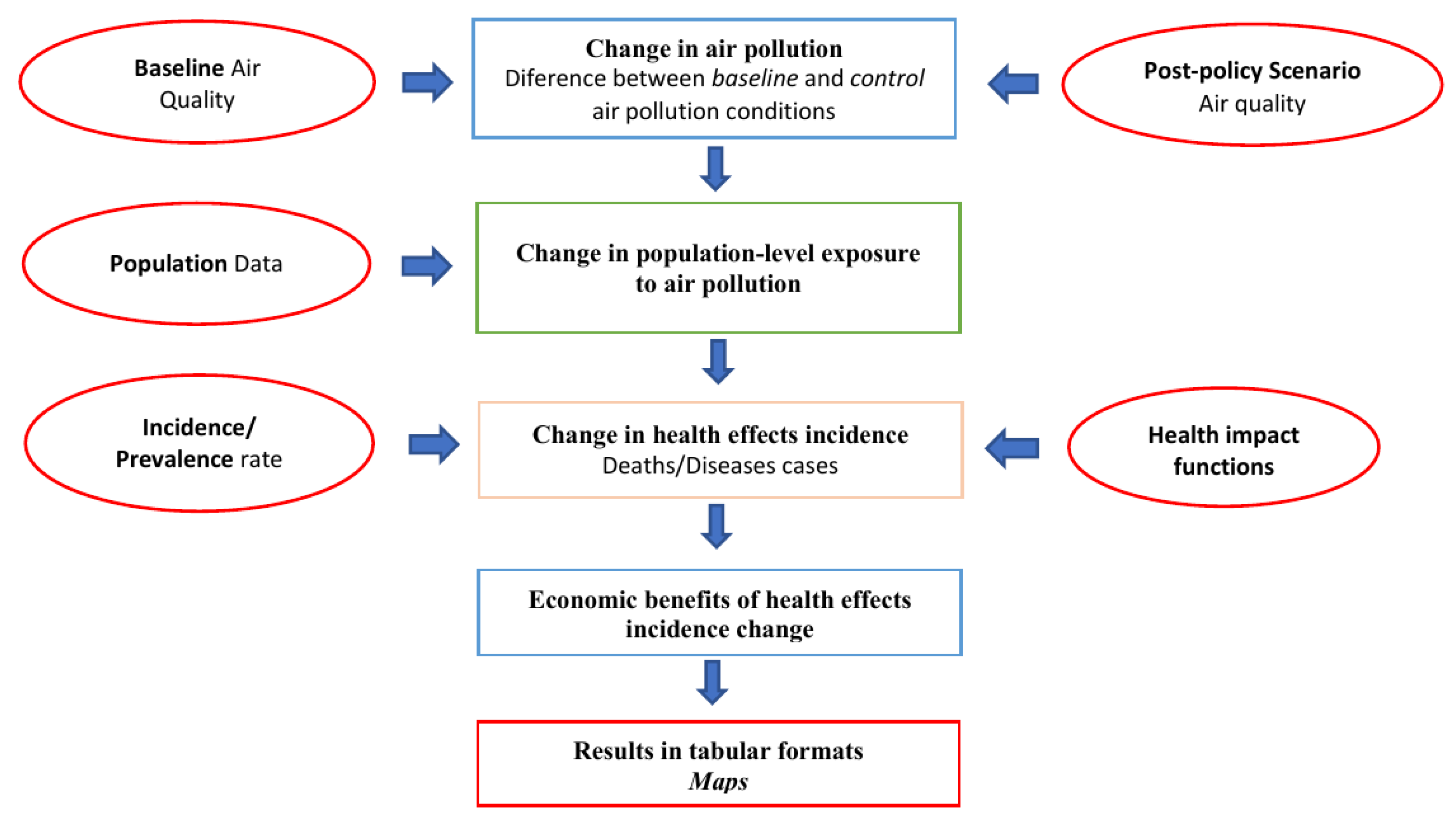

2. Methodology

2.1. Software

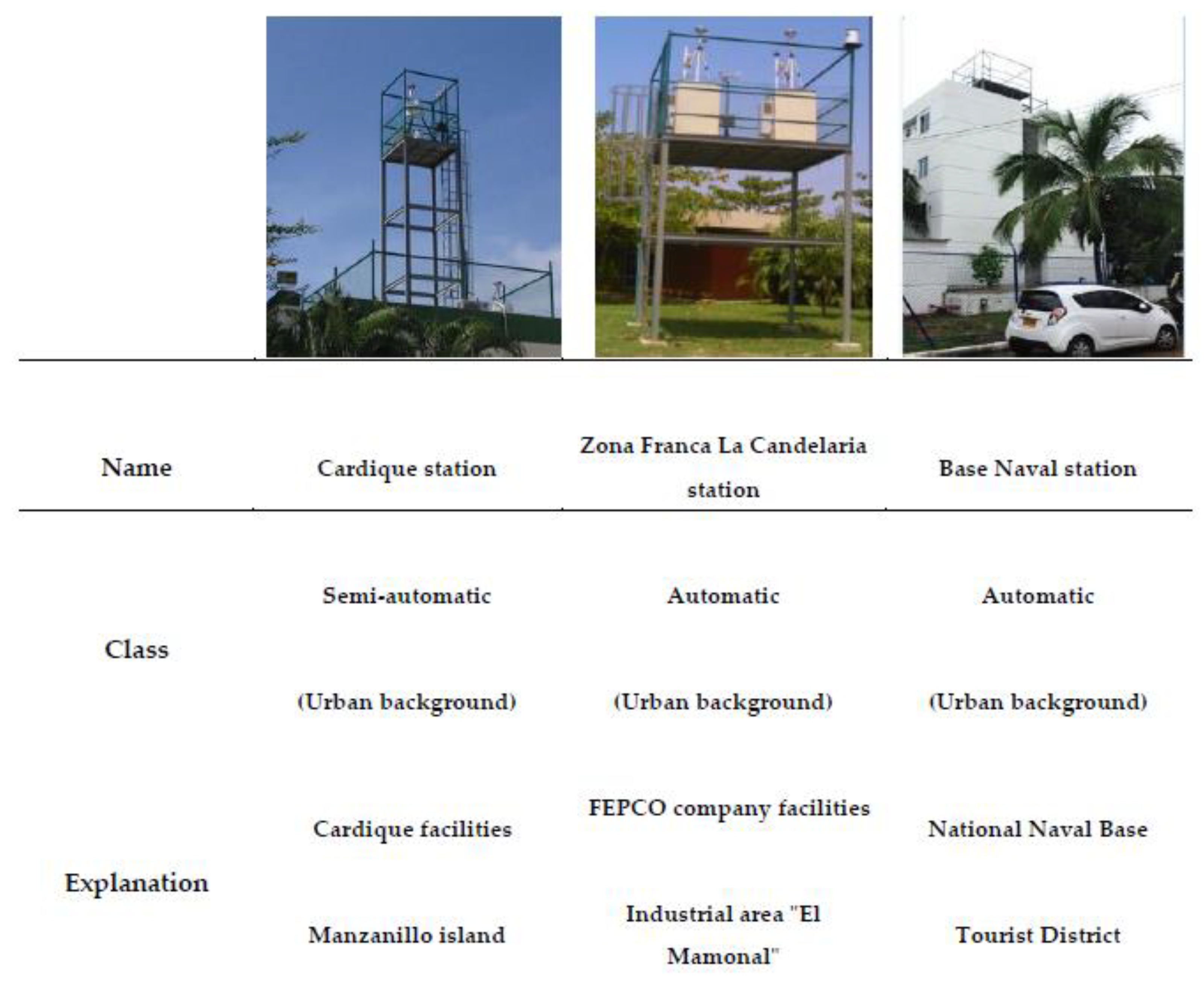

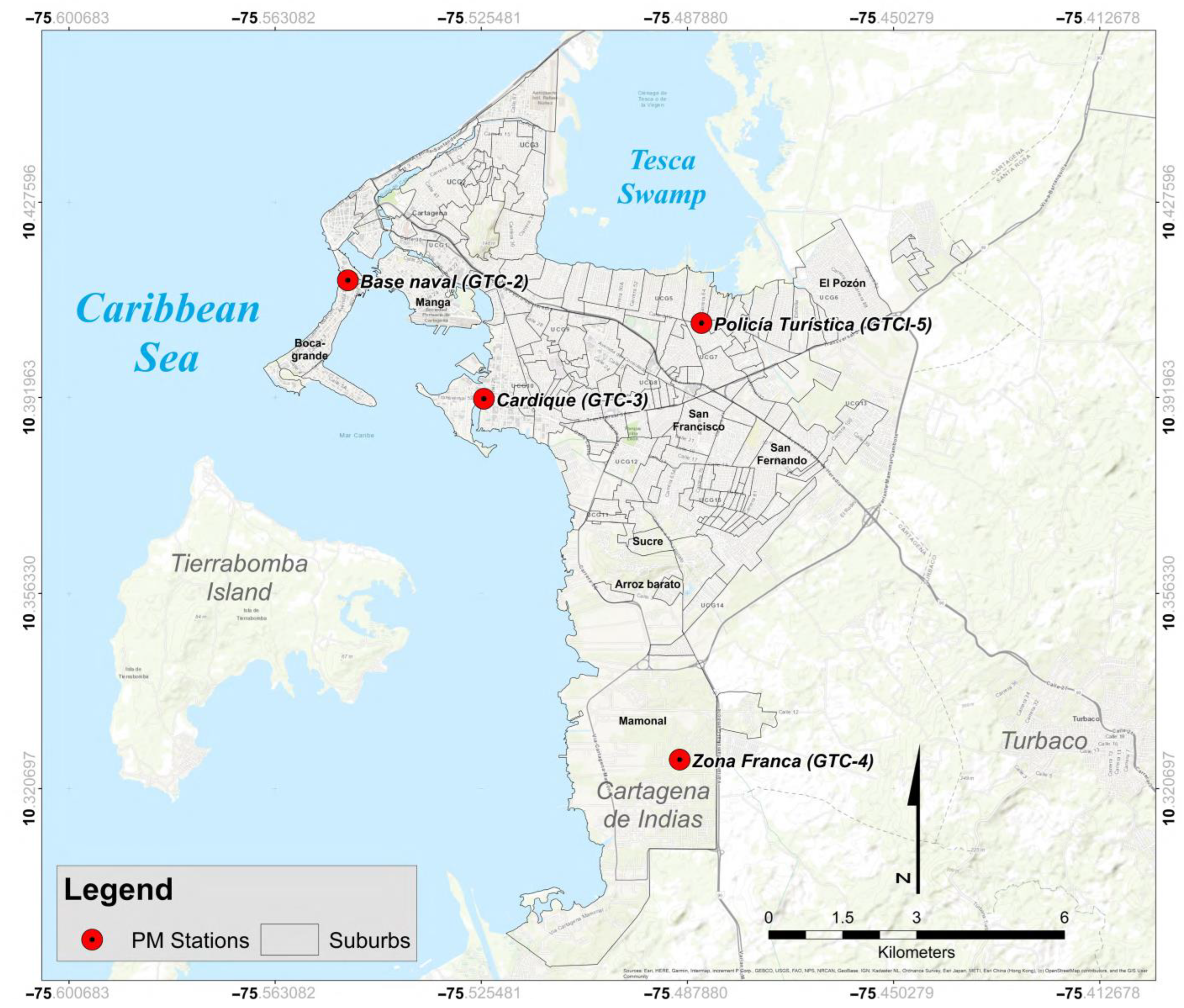

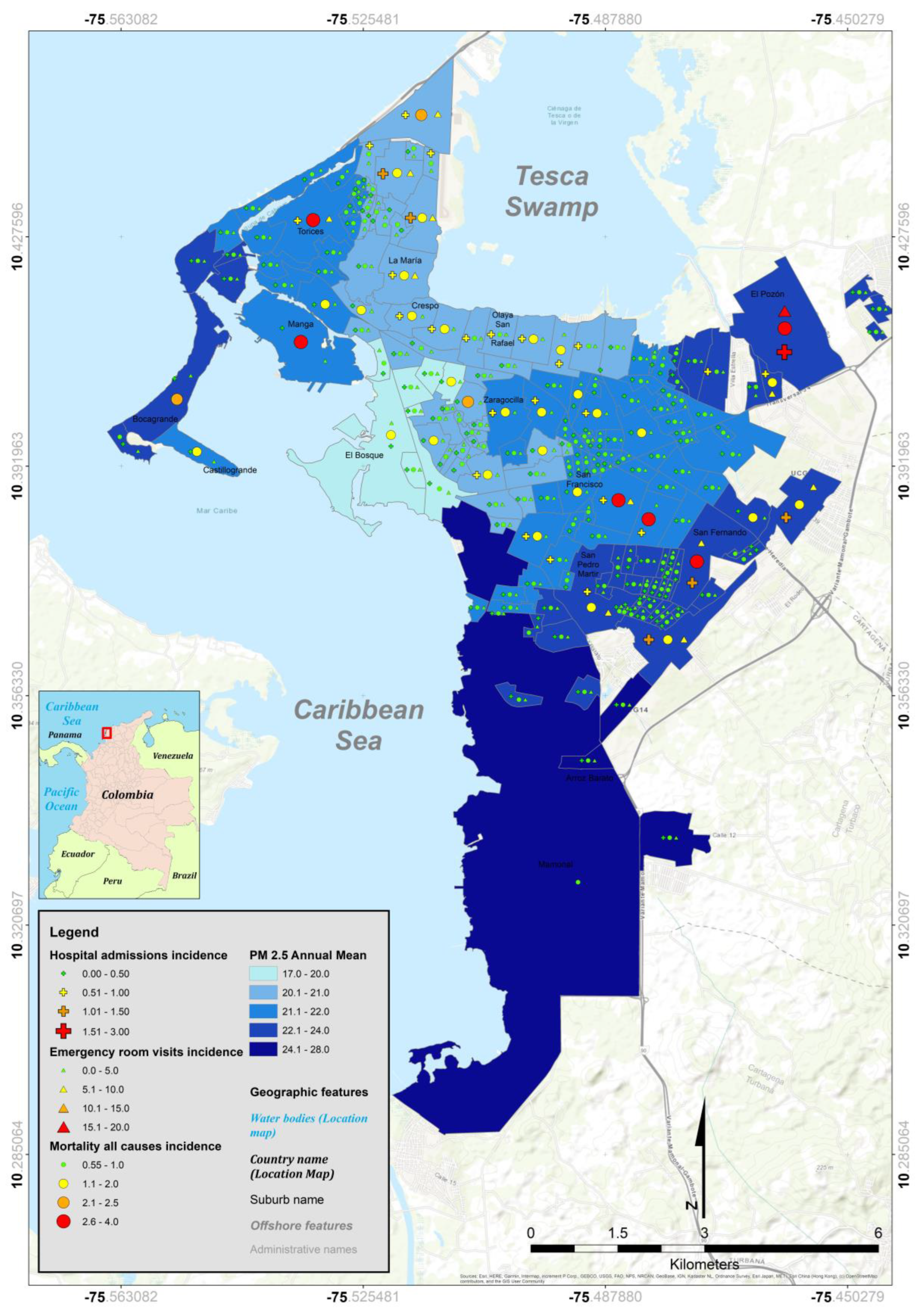

2.2. Exposure to PM2.5

Baseline Incidence Rates and Population Size by Neighborhoods

2.3. Risk Coefficients

2.4. Estimation of the Number of Disease Cases Attributable to Anthropogenic PM2.5 Exposure

2.5. Economic Assessment

- Emergency Room Visits: COP 90,000 /visit · person (2009).

- Children Hospitalizations (under 4 years) for respiratory causes: COP 1,500,000 /hospitalization (2009).

- Cost of a person’s life: A VSL of COP 1,008,000 (2009).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Number Estimation of Deaths and Morbidity Cases Avoided Due to the PM2.5 Reduction

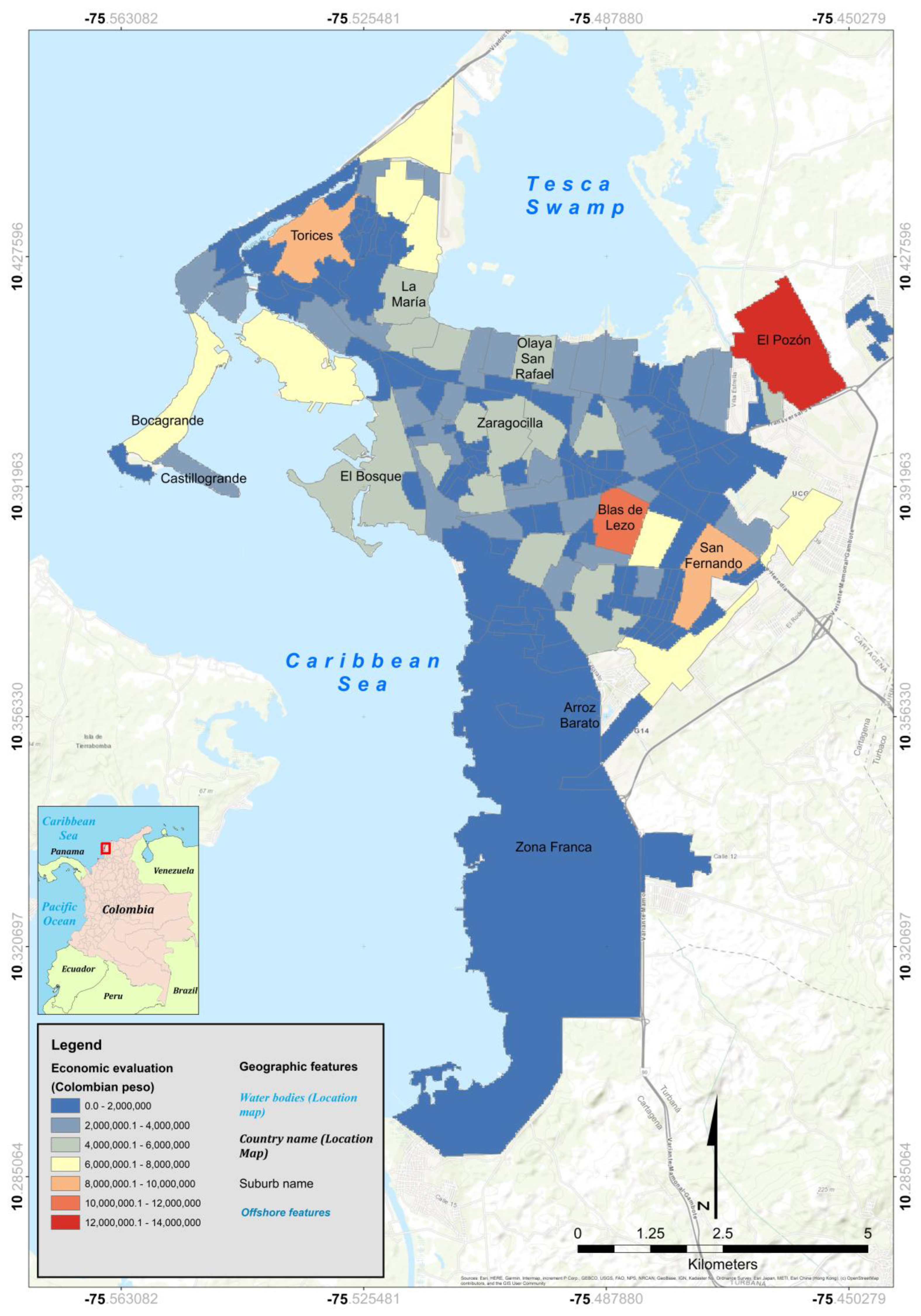

3.2. Economic Benefit Associated with Reducing Anthropogenic PM2.5 Levels

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Myong, J.-P. Health Effects of Particulate Matter. Korean J. Med. 2016, 91, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.-F.; Xu, Y.-H.; Shi, M.-H.; Lian, Y.-X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E69–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, R.B.; Lim, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cromar, K.; Shao, Y.; Reynolds, H.; Silverman, D.T.; Jones, R.R.; Park, Y.; Jerrett, M.; et al. PM2.5 air pollution and cause-specific cardiovascular disease mortality. Leuk. Res. 2020, 49, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud, “Calidad del Aire (Exterior) y Salud,” 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- World Health Organisation. Ambient (Outdoor) Air Pollution, 2018. Available online: https://www.Who.Int/En/News-Room/Fact-Sheets/Detail/Ambient-(Outdoor)-Air-Quality-and-Health (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Gehring, U.; Wijga, A.H.; Koppelman, G.H.; Vonk, J.M.; Smit, H.A.; Brunekreef, B. Air pollution and the development of asthma from birth until young adulthood. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Asthma and Air Pollution: Connecting the Dots. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Environmental Health; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundbäck, B.; Backman, H.; Lötvall, J.; Rönmark, E. Is asthma prevalence still increasing? Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2016, 10, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, V.; Berdugo, J. Incidencia del flujo vehicular en la calidad del aire en sitios críticos por población, movilidad y características geométricas de las vías en la ciudad de Cartagena. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martenies, S.E.; Wilkins, D.; Batterman, S.A. Health impact metrics for air pollution management strategies. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, J.; Fann, N.; Gumy, S.; Kim, I.; Ruggeri, G.; Mudu, P. Quantifying the Public Health Benefits of Reducing Air Pollution: Critically Assessing the Features and Capabilities of WHO’s AirQ+ and U.S. EPA’s Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program—Community Edition (BenMAP—CE). Atmosphere 2020, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program (BenMAP). In User Manual; EPA: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ostro, B.; Lipsett, M.; Mann, J.; Braxton-Owens, H.; White, M. Air Pollution and Exacerbation of Asthma in African-American Children in Los Angeles. Epidemiology 2001, 12, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, K.E.; Keen, S.L. Public health benefits of reducing exposure to ambient fine particulate matter in South Africa. Sci. Total. Environ 2019, 684, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, M.; Li, S.; Bai, Z.; Wang, Z. Combined use of land use regression and BenMAP for estimating public health benefits of reducing PM2.5 in Tianjin, China. Atmospheric Environ. 2017, 152, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, S.; Kemball-Cook, S.; Koo, B. Using BenMAP for Assessing Health Impacts of Ozone Exposure: A Case Study in San Antonio. ISEE Conf. Abstr. 2018, 1, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, J.D.; Lloyd, J.M.; Zhu, Y.; Anderton, J.; Jang, C.J.; Hubbell, B.; Fann, N. The Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program—Community Edition (BenMAP–CE): A tool to estimate the health and economic benefits of reducing air pollution. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 104, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Establecimiento Público Ambiental Cartagena. Red de Monitoreo de Calidad del Aire para la Ciudad de Cartagena; Establecimiento Público Ambiental: Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Allergy Organisations Centers. Institute for Immunological Research, 2020. Available online: https://www.worldallergy.org/wao-centers-of-excellence/latin-america/institute-for-immunological-research-colombia-2016 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- DANE. DANE, 2019. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/proyecciones-de-poblacion (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- de Jesus, A.L.; Rahman, M.; Mazaheri, M.; Thompson, H.; Knibbs, L.D.; Jeong, C.; Evans, G.; Nei, W.; Ding, A.; Qiao, L.; et al. Ultrafine particles and PM2.5 in the air of cities around the world: Are they representative of each other? Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK AIR. Site Environment Types. Department for Environent Food and Rural Affairs, 2020. Available online: https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/networks/site-types (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Ortiz-Durán, E.Y.; Rojas-Roa, N.Y. Estimación de los beneficios económicos en salud asociados a la reducción de PM10 en Bogotá. Rev. De Salud Publica 2013, 15, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- PyTorch. MIDAS, version 3.0; Alcaldía Mayor de Cartagena: Cartagena de Indias, 2016.

- Miranda, P.A.; Hoyos Sánchez, B.D. Prevalencia de asma infantil en la ciudad de Cartagena. Artículo Original 2014, 23, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- MinSalud. Ministerio de Salud de Colombia (MinSalud), 2020. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/default.aspx (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Caraballo, L.; Cadavid, A.; Mendoza, J. Prevalence of asthma in a tropical city of Colombia. Ann. Allergy 1992, 68, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Herrera, M.; Reyes, M.; Victoria, L.; Villegas, A.; Badiel, M.; Herrera, S. Asma y rinitis alérgica en pre-escolares en Cali. Colomb. Med 2003, 34, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A.; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung Cancer, Cardiopulmonary Mortality, and Long-Term Exposure to Fine Particulate Air Pollution. JAMA Net. 2002, 287, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewski, D.; Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R.T.; Ma, R.; Hughes, E.; Shi, Y.; Turner, M.C.; Pope, C.A., III; Thurston, G.; Calle, E.E.; et al. Extended Follow−Up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality; Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 5–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, G.; Badaloni, C.; Gariazzo, C.; Stafoggia, M.; Sozzi, R.; Davoli, M.; Forastiere, F. Long-Term Exposure to Urban Air Pollution and Mortality in a Cohort of More than a Million Adults in Rome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, D.L.; Peters, P.A.; van Donkelaar, A.; Goldberg, M.S.; Villeneuve, P.J.; Brion, O.; Khan, S.; Atari, D.O.; Jerrett, M.; Pope, C.A., III; et al. Risk of non-accidental and cardiovascular mortality in relation to long-term exposure to low concentrations of fine particulate matter: A Canadian National-level cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrett, M.; Burnett, R.T.; Pope, C.A., III; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.; Krewski, D.; Shi, Y.; Calle, E.; Thun, M. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, G.; YoungPong, S.N.; Koenig, J.Q.; Larson, T.V.; Sheppard, L.; Stout, J.W. An association between fine particles and asthma emergency department visits for children in Seattle. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, R.T.; Smith-Doiron, M.; Stieb, D.; Raizenne, M.E.; Brook, J.R.; Dales, R.E.; Leech, J.A.; Cakmak, S.; Krewski, D. Association between Ozone and Hospitalization for Acute Respiratory Diseases in Children Less than 2 Years of Age. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nas, T. Cost-Benefit Analysis: Theory and Application, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.A.; Hammitt, J.K. Skills of the trade: Baluing health risk reductions in benefit-cost analysis. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 2013, 4, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinestrosa, F.; Díaz, Q.F. Estudio Costo Enfermedad de Asma en Una Institución Prestadora de Servicios de Salud del Departamento de Caldas 2007–2009; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aldegunde, J.A.; Álvarez, V.; Bolaños, E.Q.; Saba, M.; Atencio, C.H. Estimation of the Vehicle Emission Factor in Different Areas of Cartagena de Indias. Rev. Cienc. 2019, 23, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldo, E.; Linares, C.; Aragonés, N.; Lumbreras, J.; Borge, R.; de la Paz, D.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Fernández-Navarro, P.; García-Pérez, J.; Pollán, M.; et al. Air quality modeling and mortality impact of fine particles reduction policies in Spain. Environ. Res. 2014, 128, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Valbuena, G.J.; Salazar-Mejía, I. La pobreza en Cartagena: Un análisis por barrios. In La Economía y el Capital Humano de Cartagena de Indias. Capítulo 1. La pobreza en Cartagena: Un Análisis por Barrios; Banco de la República de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2008; pp. 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Thunis, P.D.; Pisoni, E.; Trombetti, M.; Peduzzi, E.; Belis, J.; Wilson, E. Urban PM2.5 Atlas—Air Quality in European Cities; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. PM2.5 Annual Mean in 2016, 2020. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/pm2-5-annual-mean-in-1 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- European Environment Agency. Premature Deaths Attributable to Air Pollution, 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/media/newsreleases/many-europeans-still-exposed-to-air-pollution-2015/premature-deaths-attributable-to-air-pollution (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Wesson, K.; Fann, N.; Morris, M.; Fox, T.; Hubbell, B. A multi–pollutant, risk–based approach to air quality management: Case study for Detroit. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2010, 1, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broome, R.A.; Fann, N.; Cristina, T.J.N.; Fulcher, C.; Duc, H.; Morgan, G.G. The health benefits of reducing air pollution in Sydney, Australia. Environ. Res. 2015, 143, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniceto, K.R.D.; Macam, J.J.G.; Salmorin, E.I.F.; Sison, Z.K.J.; Mission, M.P.D.; Camacho, I.K.B.; Poso, F.D. Seasonal Mapping and Air Quality Evaluation of Total Suspended Particulate Concentration Using ArcGIS-Based Spatial Analysis in Metro Manila, Philippines. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 13th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Boracay Island, Philippines, 28–30 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.; Liang, L.; Dong, P. Monitoring, Mapping, and Modeling Spatial–Temporal Patterns of PM2.5 for Improved Understanding of Air Pollution Dynamics Using Portable Sensing Technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines. Global Update 2005, 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-SDE-PHE-OEH-06.02 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Update of WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines; 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/who-global-air-quality-guidelines (accessed on 3 December 2021).

| Mortality Category | ICD-10 Codes | Age Ranges | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–34 | 35–39 | 40–44 | 45–49 | 50–54 | 55–59 | 60–64 | 65–69 | 70–74 | 75–79 | 80+ | ||

| Mortality, All Causes | A00-Y98 | 0.1122 | 0.1562 | 0.2147 | 0.2332 | 0.3243 | 0.5351 | 0.8331 | 1.1561 | 2.0678 | 3.1045 | 9.2860 |

| Mortality, Non Accidental | A00-R99 | 0.0459 | 0.1006 | 0.1572 | 0.1996 | 0.2816 | 0.4998 | 0.7978 | 1.1166 | 2.0266 | 2.9990 | 9.1429 |

| Mortality, Ischaemic Heart Disease | I20-I25 | 0.0025 | 0.0060 | 0.0169 | 0.0167 | 0.0303 | 0.0660 | 0.1408 | 0.1578 | 0.3417 | 0.4521 | 1.1673 |

| Mortality, Respiratory | J00-J98 | 0.0038 | 0.0045 | 0.0101 | 0.0201 | 0.0213 | 0.0550 | 0.0704 | 0.0986 | 0.2592 | 0.4671 | 1.8225 |

| Mortality, Cardiopulmonary | I00-I78 J10-J18, | 0.0038 | 0.0030 | 0.0033 | 0.0067 | 0.0142 | 0.0176 | 0.0117 | 0.0276 | 0.0589 | 0.0753 | 0.2108 |

| Mortality, Cardiovascular | I20-I28 I30-I52 I60-I79 | 0.0114 | 0.0195 | 0.0422 | 0.0520 | 0.0784 | 0.1541 | 0.2786 | 0.4103 | 0.8012 | 1.2357 | 3.5773 |

| Mortality, Lung Cancer | C34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0050 | 0.0089 | 0.0198 | 0.0322 | 0.0394 | 0.0471 | 0.1130 | 0.1656 |

| Health Endpoint |

Epidemiologic Parameter (β) 95th Percentile | Pollutant | Author | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality (All Cause) | 0.0058268908 (σ = 0.00215707) RR = 1.06 (1.02–1.11) per 10 μg/m3 | PM2.5 (annual avg) | [29] | 30–99 |

| 0.0029558802 (σ = 0.00099081) RR = 1.03 (1.01–1.05) per 10 μg/m3 | [30] | 30–99 | ||

| Mortality (Non-Accidental) | 0.0039220713 (σ = 0.00049061) RR = 1.04 (1.03–1.05) per 10 μg/m3 | [31] | >30 | |

| 0.013976194 (σ = 0.000668443) RR = 1.15 (1.13–1.16) per 10 μg/m3 | [32] | >25 | ||

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 0.01655144 (σ = 0.0019384) RR = 1.18 (1.14–1.23) per 10 μg/m3 | [29] | 30–99 | |

| 0.01397619 (σ = 0.00198877) RR = 1.15 (1.11–1.20) per 10 μg/m3 | [30] | 30–99 | ||

| Respiratory | 0.00305292 (σ = 0.0039072) RR = 1.031 (0.955–1.113)~10 μg/m3 | [33] | 30–99 | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0.00861776 (σ = 0.003032173) RR = 1.09 (1.03–1.16) per 10 μg/m3 | [29] | 30–99 | |

| Cardiovascular | 0.0058268908 (σ = 0.00096276) RR = 1.06 (1.04–1.08) per 10 μg/m3 | [31] | >30 | |

| Lung Cancer | 0.01310282 (σ = 0.00428044) RR = 1.14 (1.04–1.23) per 10 μg/m3 | [29] | 30–99 | |

| Asthma Exacerbation (Cough) | 0.000985293 (σ = 0.00074712) RR = 1.03 (0.98–1.07) per 30 μg/m3 | PM2.5 (24 h-avg) | [13] | 5–18 |

| Emergency Room Visits: Asthma | 0.0147117 (σ = 0.0034923) RR = 1.15 (1.08–1.23) per 9.5 μg/m3 | [34] | <18 | |

| Hospitalization: Respiratory | 0.00814968 (σ = 0.0024771) Increase = 15.8% (t statistic 3.29) per 18 μg/m3 | [35] | <4 |

| Endpoint Groups |

* Number (% CI) | Age Range | Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | All Cause | 104 (29–177) | >29 (>25) | Annual Mean Metric |

| 53 (18–87) | ||||

| * Non-Accidental | 65 (49–81) | |||

| 227 (206–247) * | ||||

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 36 (28–44) | |||

| 31 (22–39) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 35 (24–46) | |||

| Lung Cancer | 6 (2–8) | |||

| Respiratory | 7 (1–14) | |||

| Cardiopulmonary | 4 (1–6) | |||

| Hospital Admissions: Respiratory | 48 (20–76) | <4 | Daily Metric completed with Rsoftware | |

| Emergency Room Visits: Asthma | 296 (160–427) | <18 | ||

| Endpoint Groups | ** Economic Valuation (% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | All Cause | 140.823 (39.766–247.589) |

| * Non-Accidental | 71.935 (25.292–122.335) 1 | |

| 308.473 (274.429–368.103) 2 | ||

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 49.237 (38.745–63.621) | |

| Cardiovascular | 47.735 (33.133–65.901) | |

| Lung Cancer | 7.497 (3.371–11.947) | |

| Respiratory | 9.900 (282–19.046) | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 5.201 (1.669–8.930) | |

| Hospital Admissions: Respiratory | 97.8 (39.8–154.3) | |

| Emergency Room Visits: Asthma | 38.8 (19.7–59.6) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldegunde, J.A.Á.; Bolaños, E.Q.; Fernández-Sánchez, A.; Saba, M.; Caraballo, L. Environmental and Health Benefits Assessment of Reducing PM2.5 Concentrations in Urban Areas in Developing Countries: Case Study Cartagena de Indias. Environments 2023, 10, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10030042

Aldegunde JAÁ, Bolaños EQ, Fernández-Sánchez A, Saba M, Caraballo L. Environmental and Health Benefits Assessment of Reducing PM2.5 Concentrations in Urban Areas in Developing Countries: Case Study Cartagena de Indias. Environments. 2023; 10(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldegunde, José Antonio Álvarez, Edgar Quiñones Bolaños, Adrián Fernández-Sánchez, Manuel Saba, and Luis Caraballo. 2023. "Environmental and Health Benefits Assessment of Reducing PM2.5 Concentrations in Urban Areas in Developing Countries: Case Study Cartagena de Indias" Environments 10, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10030042

APA StyleAldegunde, J. A. Á., Bolaños, E. Q., Fernández-Sánchez, A., Saba, M., & Caraballo, L. (2023). Environmental and Health Benefits Assessment of Reducing PM2.5 Concentrations in Urban Areas in Developing Countries: Case Study Cartagena de Indias. Environments, 10(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10030042