Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain: A Chain Mediation Model of Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain

1.2. Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress

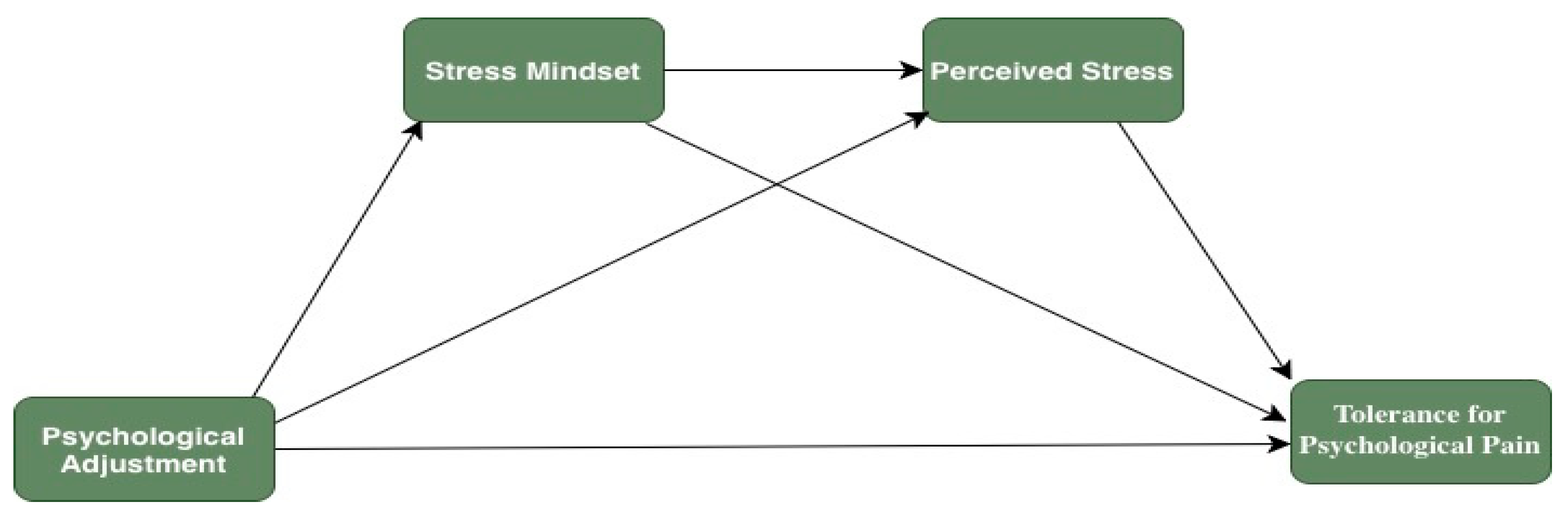

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Power Analysis

2.3. Measures

- Tolerance for Mental Pain Scale (TMPS). This scale is a self-report instrument consisting of 10 items (e.g., “Believe that my pain will go away.”) designed to measure individuals’ tolerance levels for psychological pain (Meerwijk et al., 2019). On this five-point Likert scale, higher scores indicate increased tolerance for psychological pain. The Cronbach alpha value of the scale in Turkish culture is 0.98 (Demirkol et al., 2019). The CFA results for this study are as follows: CMIN/df 4.09, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94 and RMSEA = 0.066. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient of the scale is 0.73.

- Brief Adjustment Scale-6 (BASE). The scale was developed to assess psychological adjustment (Cruz et al., 2020) and consists of six items (e.g., “To what extent did you feel unhappy, insecure, and depressed this week?”). The scale is a seven-point Likert (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) type. As the scores obtained from the scale decrease, psychological adjustment increases (Cruz et al., 2020). Cronbach’s α of the scale in Turkish culture is 0.88 (M. Yıldırım & Solmaz, 2020). The CFA results for this study are as follows: CMIN/df 4.47, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98 and RMSEA = 0.070. Additionally, Cronbach’s α for the scale was found to be 0.90.

- Although the Brief Adjustment Scale–6 was originally developed for university student populations, its core constructs reflect general psychological adjustment processes that are not restricted to student status. In the present study, internal consistency and CFA indicators obtained from the current sample supported the appropriateness of its use with a broader age and occupational range.

- The Perceived Stress Scale. The scale is a 14-item (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and stressed?”) self-report instrument using a five-point Likert format (0 = never, 4 = very often) to assess perceived stress (Cohen et al., 1983). An increase in scores indicates that the individual’s stress perception is high. The scale’s reliability coefficients in Turkish culture are above 0.80 (Eskin et al., 2013). The CFA results for this study are as follows: CMIN/df 4.20, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93 and RMSEA = 0.067. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was calculated to be 0.82.

- Stress Mindset Measure. The scale is a five-point Likert-type self-report instrument (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) developed to assess individuals’ beliefs about the consequences of stress (Crum et al., 2013). The scale consists of eight items (e.g., “Experiencing this stress depletes my health and vitality.”). An increase in scores indicates an increase in the individual’s level of functional evaluation regarding the consequences of stress. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s Omega (SPSS 25) reliability values of the scale in Turkish culture are above 0.80 (Türk & Çelik, 2024). The CFA results for this study are as follows: CMIN/df 4.41, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95 and RMSEA = 0.069. In the present study, Cronbach’s α of the scale was calculated to be 0.82.

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

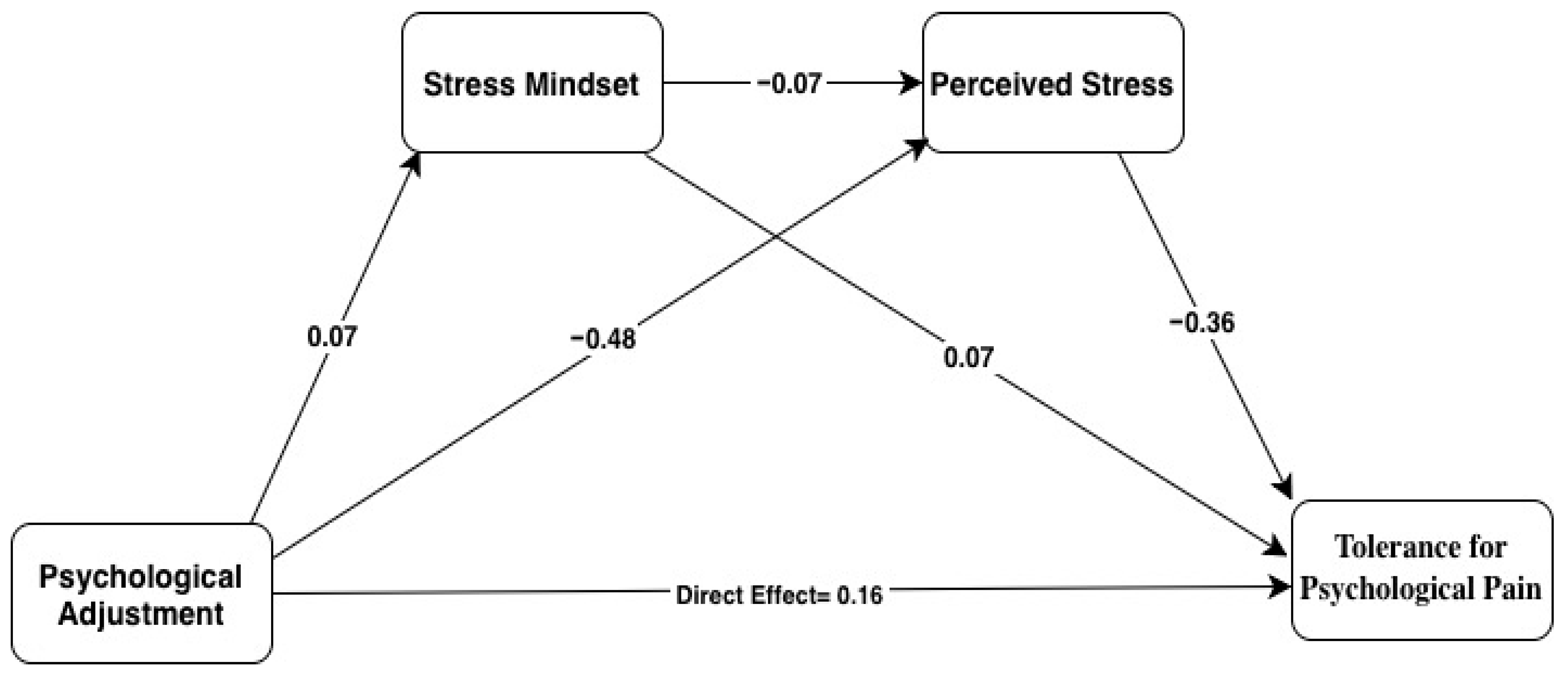

Chain Mediational Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alker, L. A. (2019). Distress tolerance as a mediator of the relation between stress mindset and anxiety [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Twente]. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G., Türk, N., & Kaya, A. (2024). Psychological vulnerability, emotional problems, and quality-of-life: Validation of the brief suicide cognitions scale for Turkish college students. Current Psychology, 43(24), 21009–21018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabrera, Q., Gómez-Romero, M. J., Chamarro, A., & Limonero, J. T. (2024). The relationship between suicidal behavior and perceived stress: The role of cognitive emotional regulation and problematic alcohol use in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Health Psychology, 29(9), 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantjes, J., & Kagee, A. (2018). Common mental disorders and psychological adjustment among individuals seeking HIV testing: A study protocol to explore implications for mental health care systems. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. R., Fergus, T. A., & Orcutt, H. K. (2017). Examining the specific dimensions of distress tolerance that prospectively predict perceived stress. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(3), 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başaran, İ. E. (2005). Eğitim psikolojisi [Educational psychology]. Nobel Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Batmaz, H., Türk, N., & Doğrusever, C. (2021). The mediating role of hope and loneliness in the relationship between meaningful life and psychological resilience in the COVİD-19 Pandemic during. Anemon Muş Alparslan Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 9(5), 1403–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G., Orbach, I., Mikulincer, M., Iohan, M., Gilboa-Schechtman, E., & Grossman-Giron, A. (2019). Reexamining the mental pain–suicidality link in adolescence: The role of tolerance for mental pain. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(4), 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergin, A. J., & Pakenham, K. I. (2016). The stress-buffering role of mindfulness in the relationship between perceived stress and psychological adjustment. Mindfulness, 7, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, D., Simon, C. D., Chan, W. Y., & Tran, N. (2014). A life domains perspective on acculturation and psychological adjustment: A study of refugees from the former Soviet Union. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørndal, L. D., Ebrahimi, O. V., Røysamb, E., Karstoft, K. I., Czajkowski, N. O., & Nes, R. B. (2024). Stressful life events exhibit complex patterns of associations with depressive symptoms in two population-based samples using network analysis. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 349, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. S., & Gregersen, H. B. (1991). Antecedents to cross-cultural adjustment for expatriates in Pacific Rim assignments. Human Relations, 44, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, S. J., & McLean, L. A. (2015). Interrelations of stress, optimism and control in older people’s psychological adjustment. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 34(2), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş., Kılıç Çakmak, E., Akgün, Ö. E., Karadeniz, Ş., & Demirel, F. (2014). Eğitimde bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri [Scientific research methods in education]. Pegem Academy Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Qu, L., & Hong, R. Y. (2022). Pathways linking the big five to psychological distress: Exploring the mediating roles of stress mindset and coping flexibility. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(9), 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Cheng, Y., Zhao, W., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Psychological pain in depressive disorder: A concept analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(13–14), 4128–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. L., & Kuo, P. H. (2020). Effects of perceived stress and resilience on suicidal behaviours in early adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(6), 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conejero, I., Olié, E., Calati, R., Ducasse, D., & Courtet, P. (2018). Psychological pain, depression, and suicide: Recent evidences and future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Martin, A., & Fath, S. (2017). The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(4), 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R. A., Peterson, A. P., Fagan, C., Black, W., & Cooper, L. (2020). Evaluation of the brief adjustment scale–6 (BASE-6): A measure of general psychological adjustment for measurement-based care. Psychological Services, 17(3), 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetiner, E., Sayın-Karakaş, G., Selçuk, O. C., & Şakiroğlu, M. (2018). Perceived stress and university adaptation process: The mediating role of mindfulness. Nesne Journal of Psychology, 6(13), 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınaroğlu, M., Yılmazer, E., Noyan Ahlatcioglu, E., Ülker, S. V., & Hızlı Sayar, G. (2025). Psychological impact of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of PTSD, depression, and anxiety among Turkish adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1664212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, M. E., Tamam, L., Namlı, Z., & Eriş Davul, Ö. (2019). Validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the tolerance for mental pain scale-10. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(4), 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğrusever, C., Türk, N., & Batmaz, H. (2022). The mediating role of meaningful life in the relationship between self-esteem and psychological resilience. İnönü Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 23(2), 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducasse, D., Holden, R. R., Boyer, L., Artero, S., Calati, R., Guillaume, S., & Olie, E. (2017). Psychological pain in suicidality: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(3), 16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, E. B., Lanier, M., Blakey, S. M., Wagner, H. R., & Tsai, J. (2021). Suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of COVID-19-related stress, social isolation, and financial strain. Depression and Anxiety, 38(7), 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, M., Harlak, H., Demirkıran, F., & Dereboy, Ç. (2013). Algılanan stres ölçeğinin Türkçeye uyarlanması: Güvenirlik ve geçerlik analizi. New Symposium Journal, 51(3), 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski, N., Koopman, H., Kraaij, V., & ten Cate, R. (2009). Brief report: Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychological adjustment in adolescents with a chronic disease. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatun, O., & Kurtça, T. T. (2024). Perceived Stress, hope, and life satisfaction among college students: A two-wave, half-longitudinal study from Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K., Michalak, M., Kopciuch, D., Bryl, W., Kus, K., Nowakowska, E., & Paczkowska, A. (2024). The prevalence and correlates of anxiety, stress, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances in Poland after the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian War 2022. Healthcare, 12(18), 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebschmann, N. A., & Sheets, E. S. (2020). The right mindset: Stress mindset moderates the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 33(3), 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, W. G., & Sandler, J. (1967). On the concept of pain, with special reference to depression and psychogenic pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(1), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journault, A. A., & Lupien, S. J. (2024). Stress mindsets matter: An overview of how individuals think about stress, its effect on biopsychosocial processes, and what we can do about it. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 160, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, J. J., & Hamilton, K. (2019). Stress mindset. In M. D. Gelman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Klussman, K., Lindeman, M. I. H., Nichols, A. L., & Langer, J. (2021). Fostering stress resilience among business students: The role of stress mindset and self-connection. Psychological Reports, 124(4), 1462–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferton, J. A., Fischer, S., Ebert, D. D., Stenzel, N. M., & Zimmermann, J. (2020). The effects of stress beliefs on daily affective stress responses. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(4), 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., & Stepanovic, J. (2011). Stress and personality. Psychiatriki, 22(4), 290–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levi-Belz, Y., Gavish-Marom, T., Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C., Sarchiapone, M., & Wasserman, D. (2019). Psychosocial factors correlated with undisclosed suicide attempts to significant others: Findings from the adolescence SEYLE study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(3), 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindert, J., Lee, L. O., Weisskopf, M. G., McKee, M., Sehner, S., & Spiro, A., III. (2020). Threats to belonging—Stressful life events and mental health symptoms in aging men—A longitudinal cohort study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 575979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansell, P. C. (2021). Stress mindset in athletes: Investigating the relationships between beliefs, challenge and threat with psychological wellbeing. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 57, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerwijk, E. L., Mikulincer, M., & Weiss, S. J. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of the tolerance for mental pain scale in United States adults. Psychiatry Research, 273, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, J., Goldberg, X., López-Sola, C., Nadal, R., Armario, A., Andero, R., Giraldo, J., Ortiz, J., Cardoner, N., & Palao, D. (2019). Perceived stress, anxiety and depression among undergraduate students: An online survey study. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 8(1), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onan, N., Barlas, G. Ü. L., Karaca, S., Yildirim, N., Taskiran, O., & Sumeli, F. (2015). The relations between perceived stress, communication skills and psychological symptoms in oncology nurses. Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences, 5(3), 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orbach, I., Mikulincer, M., Sirota, P., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2003). Mental pain: A multidimensional operationalization and definition. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(3), 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, Y., Otsuki, H., Imamoto, A., Kinjo, A., Fujii, M., Kuwabara, Y., Kondo, Y., & Suyama, Y. (2021). Suicide rates during social crises: Changes in the suicide rate in Japan after the Great East Japan earthquake and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 140, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgüven, E. (1992). Hacettepe personality inventory handbook. Odak Offset Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D., Yu, A., Metz, S. E., Tsukayama, E., Crum, A. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2019). Beliefs about stress attenuate the relation among adverse life events, perceived distress, and self-control. Child Development, 89(6), 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, S., Wu, J., Zheng, D., Xu, T., Hou, Y., Wen, J., & Liu, J. (2025). The effect of stress mindset on psychological pain: The chain mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal and self-identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1517522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Interior. (2024). Türkiye’s strength in unity and solidarity was tested by the earthquake; The disaster of the century transformed into the solidarity of the century! Available online: https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/turkiyenin-birlik-ve-dayanisma-gucu-depremle-sinandi-asrin-felaketi-asrin-dayanismasina-donustu8 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Rohner, R. P. (1975). They Love Me, They Love Me Not: A worldwide study of the effects of parental acceptance and recetion. HRAF Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R. P. (1986). The warmth dimension: Foundations of parental acceptance-rejection theory. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R. P., & Britner, P. A. (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Crosscultural Research, 36(1), 16–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, R. P., Saavedra, J. M., & Granum, E. O. (1978). Development and validation of the personality assessment questionnaire: Test manual. Connecticut University Research Foundation, Storrs, Catholic University of America. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED159502 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Ruiz-Fernández, M. D., Ramos-Pichardo, J. D., Ibáñez-Masero, O., Cabrera-Troya, J., Carmona-Rega, M. I., & Ortega-Galán, Á. M. (2020). Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21–22), 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, E., Karakuş, B. Ş., & Demir, E. (2024). Economic uncertainty and mental health: Global evidence, 1991 to 2019. SSM-Population Health, 27, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satıcı, B., Gocet-Tekin, E., Deniz, M., Satici, S. A., & Yilmaz, F. B. (2024). Mindfulness and well-being: A longitudinal serial mediation model of psychological adjustment and COVID-19 Fear. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, C. L. (2009). Psychological adjustment. In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), The encyclopedia of positive psychology. Available online: http://librarun.org/book/23232/817 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sehlikoğlu, Ş., Yıldız, S., Kurt, O., Emir, B. S., & Sehlikoğlu, K. (2024). Investigation of suicide attempt, impulsivity, psychological pain and depression in earthquake survivors affected by the February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaraş-centered earthquake. Journal of Harran University Medical Faculty, 21(3), 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelef, L., Fruchter, E., Hassidim, A., & Zalsman, G. (2015). Emotional regulation of mental pain as moderator of suicidal ideation in military settings. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F. C., Ferrreira, M. T., & Souza-Talarico, J. N. (2023). Mapping stress-mindset definitions, measurements and associated factors: A scope review. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 153, 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. E., Hoeksema-Nolen, S., Fredrickson, B., & Loftus, G. R. (2016). Atkinson and Hilgard’s introduction to psychology (16th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Spătaru, B., Podină, I. R., Tulbure, B. T., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2024). A longitudinal examination of appraisal, coping, stress, and mental health in students: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. Stress Health, 40(5), e3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhasree, G., Jeyavel, S., Eapen, J. C., & Deepthi, D. P. (2023). Stress mindset as a mediator between self-efficacy and coping styles. Cogent Psychology, 10(1), 2255048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Li, B. J., Zhang, H., & Zhang, G. (2023). Social media use for coping with stress and psychological adjustment: A transactional model of stress and coping perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1140312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Stephan, Y., Sesker, A. A., & Terracciano, A. (2023). Purpose in life, stress mindset, and perceived stress: Test of a mediational model. Personality and Individual Differences, 210, 112227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamizi, N. M. B. M., Perveen, A., Hamzah, H., & Folashade, A. T. (2024). Relationship of psychological adjustment, anxiety, stress, depression, suicide ideation, and social support among university students. International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences, 14(6), 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, N. A., Bayazi, M. H., & Shakerinasab, M. (2020). The relationship between islamic coping methods and psychological well-being with adaptation and pain tolerance in patients with breast cancer. Quarterly Journal of Health Psychology, 9(1), 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Turgut, M. N. A., Ertürk, Ö. S., Karslı, F., & Şakiroğlu, M. (2020). A mediation variable in relation to perceived stres and adaptation to university life: Separation anxiety. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 35(2), 338–353. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. (2024). İç göç istatistikleri [Internal migration statistics], 2023. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Ic-Goc-Istatistikleri-2023-53676#:~:text=Di%C4%9Fer%20bir%20ifadeyle%20T%C3%BCrkiye’de,1’ini%20ise%20kad%C4%B1nlar%20olu%C5%9Fturdu (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Türk, N., Arslan, G., Kaya, A., Güç, E., & Turan, M. E. (2024a). Psychological maltreatment, meaning-centered coping, psychological flexibility, and suicide cognitions: A moderated mediation model. Child Abuse & Neglect, 152, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, N., & Çelik, M. (2024). Psychometric properties of the Turkish adaptation of stress mindset measure. Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 16(1), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, N., Özmen, M., & Derin, S. (2025a). Psychological strain and suicide rumination among university satudents: Exploring the mediating and moderating roles of depression, resilient coping, and perceived social support. Healthcare, 13(15), 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, N., Yasdiman, M. B., & Kaya, A. (2024b). Defeat, entrapment and suicidal ideation in a Turkish community sample of young adults: An examination of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional (IMV) model of suicidal behaviour. International Review of Psychiatry, 36(4–5), 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, N., Yildirim, M., Batmaz, H., Aziz, I. A., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2025b). Resilience and meaning-centered coping as mediators in the relationship between life satisfaction and posttraumatic outcomes among earthquake survivors in Turkey. Medicine, 104(10), e41712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiten, W., Yost Hammer, E., & Dunn, D. S. (2011). Psychology and contemporary Life: Human adjustment (10th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S. E., & Ginty, A. T. (2024). A stress-is-enhancing mindset is associated with lower traumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 37(3), 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025). Fragile and conflict-affected situations: Intertwined crises, multiple vulnerabilities [Press release]. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/06/27/fragile-and-conflict-affected-situations-intertwined-crises-multiple-vulnerabilities (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The global risks report 2025: 20th edition (Insight report). Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- World Health Organization. (2025). Health: Who is health emergency appeal 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-s-health-emergency-appeal-2025 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Yeşiloğlu, C., Tamam, L., Demirkol, M. E., Namlı, Z., & Karaytuğ, M. O. (2023). Associations between the suicidal ideation and the tolerance for psychological pain and tolerance for physical pain in patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 19, 2283–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M., & Solmaz, F. (2020). Testing a Turkish adaption of the brief psychological adjustment scale and assessing the relation to mental health. Studies in Psychology, 41(1), 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, O., Batmaz, H., & Türk, N. (2026). Parallel mediation of psychological flexibility and vulnerability between multiple-screen addiction and mental health outcomes in adolescents. BMC Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandifar, A., Badrfam, R., Yazdani, S., Arzaghi, S. M., Rahimi, F., Ghasemi, S., Khamisabadi, S., Khonsari, N. M., & Qorbani, M. (2020). Prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, stress and perceived stress in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 19, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W., Ma, S., Xu, Y., & Wang, R. (2024). The roles of stress mindset and personality in the impact of life stress on emotional well-being in the context of COVID-19 confinement: A diary study. Appl Psychol Health Well Being, 16(3), 1178–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N., Bai, B., & Zhu, J. (2023). Stress mindset, proactive coping behavior, and posttraumatic growth among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(3), 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S., Li, X., Li, Y., Cao, Y., Mi, G., Chen, L., Ye, Z., & Niu, L. (2025). Reframing stress: The impact of stress mindset on adolescent sleep health. Journal of Research on Adolescent, 35(3), e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X., Sang, D., & Wang, L. (2004). Acculturation and subjective well-being of Chinese students in Australia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 241 | 34.0 |

| Female | 468 | 66.0 | |

| Age | Range | 18–51 | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.08 (6.41) | ||

| Education Level | High school | 133 | 18.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 507 | 71.5 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 69 | 9.7 | |

| Socioeconomic Status | Poor | 126 | 17.8 |

| Moderate | 547 | 77.2 | |

| Good | 36 | 5.1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 = Tolerance for psychological pain | 1 | |||

| 2 = Psychological adjustment | 0.46 ** | 1 | ||

| 3 = Stress mindset | 0.14 * | 0.10 ** | 1 | |

| 4 = Perceived stress | −0.51 ** | −0.68 * | −0.14 | 1 |

| Mean | 32.22 | 24.91 | 8.66 | 21.00 |

| Std. deviation | 7.04 | 9.49 | 6.60 | 6.80 |

| Skewness | −0.00 | −0.15 | 0.45 | 0.05 |

| Kurtosis | 0.30 | −0.67 | −0.43 | 0.23 |

| Stress Mindset | Perceived Stress | Tolerance for Psychological Pain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Psychological adjustment | 0.07 | 0.001 | −0.48 | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.001 |

| Stress mindset | ------ | ------ | −0.07 | 0.005 | 0.07 | 0.005 |

| Perceived stress | ------ | ------ | ------ | ------ | −0.36 | 0.005 |

| Constant | 6.92 | 0.001 | 33.55 | 0.001 | 35.09 | 0.005 |

| R = 0.10, R2 = 0.010 | R = 0.68, R2 = 0.46 | R = 0.54; R2 = 0.29 | ||||

| F(1, 707) = 7.215 | F(2, 706) = 302.2 | F(3, 705) = 95.84 | ||||

| Estimates of Point β | The lowest | The highest | ||||

| Ind1 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.012 | |||

| Ind2 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.22 | |||

| Ind3 | 0.0018 | 0.0010 | 0.004 | |||

| Model Pathways | Coefficient | Confidence Interval (%95) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| a → b | 0.16 | 0.10 ** | 0.23 ** |

| a → c | 0.07 | 0.017 * | 0.12 * |

| a → d | −0.48 | −0.52 * | −0.44 * |

| c → d | −0.07 | −0.13 * | −0.011 * |

| c → b | 0.07 | 0.006 * | 0.14 * |

| d → b | −0.36 | −0.45 * | −0.26 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Çelik, M.; Batmaz, H.; Türk, N.; Derin, S. Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain: A Chain Mediation Model of Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010151

Çelik M, Batmaz H, Türk N, Derin S. Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain: A Chain Mediation Model of Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010151

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇelik, Metin, Hasan Batmaz, Nuri Türk, and Sümeyye Derin. 2026. "Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain: A Chain Mediation Model of Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010151

APA StyleÇelik, M., Batmaz, H., Türk, N., & Derin, S. (2026). Psychological Adjustment and Tolerance for Psychological Pain: A Chain Mediation Model of Stress Mindset and Perceived Stress. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010151