Retention on Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder in Justice-Involved Individuals: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in the Criminal Justice System

1.2. Treatment Utilization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Sample

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Moderating and Control Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. MOUD Retention

3.3. Modeling MOUD Retention Outcomes

3.4. Characteristics by Justice Involved Status

Multivariate Analysis CJ Involvement and Days on MOUD

3.5. Predictors of Days on MOUD

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agbese, E., Leslie, D. L., Manhapra, A., & Rosenheck, R. (2020). Early discontinuation of buprenorphine therapy for opioid use disorder among privately insured adults. Psychiatric Services, 71, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F. Z., Andraka-Christou, B., Clark, M. H., Totaram, R., Atkins, D. N., & Del Pozo, B. (2022). Barriers to medications for opioid use disorder in the court system: Provider availability, provider “trustworthiness,” and cost. Health Justice, 10(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, I. A., Stern, M. F., Yamashita, T. E., Mueller, S. R., Baggett, T. P., & Blatchford, P. J. (2016). Clinical risk factors for death after release from prison in Washington state: A nested case-control study. Addiction, 111(3), 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booty, M. D., Harp, K., Batty, E., Knudsen, H. K., Staton, M., & Oser, C. B. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to the use of medication for opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system: Perspectives from clinicians. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 149, 209051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovell-Ammon, B. J., Yan, S., Dunn, D., Evans, E. A., Friedmann, P. D., Walley, A. Y., & LaRochelle, M. R. (2024). Prison buprenorphine implementation and postrelease opioid use disorder outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 7(3), e242732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, M. D., & Jansson, M. (2018). Kernel-based semiparametric estimators: Small bandwidth asymptotics and bootstrap consistency. Econometrica, 86(3), 955–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. (2024). Quality ID #468: Continuity of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder (OUD) (MIPS clinical quality measures (CQMS)). Available online: https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_quality_measure_specifications/CQM-Measures/2025_Measure_468_MIPSCQM.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Ciccarone, D. (2021). The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion Psychiatry, 34(4), 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, D. M., Zanis, D. A., Wesnoski, S. A., Palman, N., Gur, A., Lynch, K. G., & McKay, J. R. (2013). Does mandating offenders to treatment improve completion rates? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(4), 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debbaut, S. (2022). The legitimacy of criminalizing drugs: Applying the ‘harm principle’ of John Stuart Mill to contemporary decision-making. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 68, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, J. A., Hertz, M. F., Dunlap, L. J., Richardson, J. S., Wolicki, S. B., Biggers, B. B., Edlund, M. J., Bohm, M. K., Turcios, D., Jiang, X., & Zhou, H. (2024). The medications for opioid use disorder study: Methods and initial outcomes from an 18-month study of patients in treatment for opioid use disorder. Public Health Reports, 139(4), 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A. K., Harris, A. H., Rosenthal, J., Blue-Howells, J., Clark, S., McGuire, J., Timko, C., Frayne, S. M., Smelson, D., Oliva, E., & Binswanger, I. (2016). Receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder by justice-involved U.S. veterans health administration patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florence, C., Luo, F., & Rice, K. (2021). The economic burden of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2017. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, R. M., Tegge, A. N., Freitas-Lemos, R., Cabral, D., & Bickel, W. K. (2025). Beyond the first try: How many quit attempts are necessary to achieve substance use cessation? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 267, 112525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, C. E., Ostlie, E., Scott, C. K., Dennis, M. L., Carnevale, J., & Watson, D. P. (2021). A scoping review of factors that influence opioid overdose prevention for justice-involved populations. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, Policy, 16(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guastaferro, W. P., Koetzle, D., Lutgen-Nieves, L., & Teasdale, B. (2022). Opioid agonist treatment recipients within criminal justice-involved populations. Substance Use & Misuse, 57(5), 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachtel, H., Vogel, T., & Huber, C. G. (2019). Mandated treatment and its impact on therapeutic process and outcome factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. M., Noor-E-Alam, M., Mohite, P., Islam, M. S., Modestino, A. S., Peckham, A. M., Young, L. D., & Young, G. J. (2021). Patterns of patient discontinuation from buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid use disorder: A study of a commercially insured population in Massachusetts. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 131, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelton, E., Mugleston, M., Bilmas, S., Terry, A., & Waters, R. C. (2025). A buprenorphine retention report to measure opioid use disorder care metrics and guide outreach. Substance Use & Addiction Journal, 47(1), 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T., Nasser, N., & Mitra, A. (2024). Overview of best practices for buprenorphine initiation in the emergency department. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. J., Wessel, C. B., Levine, R., Downer, K., Raymond, M., Osakue, D., Hassan, I., Merlin, J. S., & Liebschutz, J. M. (2022). Factors associated with long-term retention in buprenorphine-based addiction treatment programs: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(2), 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M. L., Alford, D. P., Kotz, M. M., Levounis, P., Mandell, T. W., Meyer, M., Salsitz, E. A., Wetterau, N., & Wyatt, S. A. (2011). Statement of the american society of addiction medicine consensus panel on the use of buprenorphine in office-based treatment of opioid addiction. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(4), 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, N., Picher, C. E., Feder, K. A., & Saloner, B. (2017). Only one in twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Affairs, 36(12), 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, N., Williams, A. R., Saloner, B., & Cerdá, M. (2021). Who stays in medication treatment for opioid use disorder? A national study of outpatient specialty treatment settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 126, 108329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langabeer, J. R., Champagne-Langabeer, T., Yatsco, A. J., O’Neal, M. M., Cardenas-Turanzas, M., Prater, S., Luber, S., Stotts, A., Fadial, T., Khraish, G., & Wang, H. (2021). Feasibility and outcomes from an integrated bridge treatment program for opioid use disorder. Journal of The American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 2(2), e12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langabeer, J. R., Vega, F. R., Cardenas-Turanzas, M., Cohen, A. S., Lalani, K., & Champagne-Langabeer, T. (2024). How financial beliefs and behaviors influence the financial health of individuals struggling with opioid use disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 14(5), 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Lu, X., & Ullah, A. (2003). Multivariate local polynomial regression for estimating average derivatives. Journal of Nonparametric Statistics, 15(4–5), 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Racine, J. (2004). Cross-validated local linear nonparametric regression. Statistica Sinica, 14(2), 485–512. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K. E., Roberts, W., Reid, H. H., Smith, K. M. Z., Oberleitner, L. M. S., & McKee, S. A. (2019). Effectiveness of medication assisted treatment for opioid use in prison and jail settings: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 99, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Medications for opioid use disorder save lives. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment [NAABT]. (n.d.). Dosing guide for optimal management of opioid dependence: Dosing guidance for SUBOXONE® & SUBUTEX® [PDF]. Available online: https://www.naabt.org/documents/Suboxone_dosing_guide.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Pivovarova, E., Taxman, F. S., Boland, A. K., Smelson, D. A., Lemon, S. C., & Friedmann, P. D. (2023). Facilitators and barriers to collaboration between drug courts and community-based medication for opioid use disorder providers. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 147, 208950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisch, D. W., Fye, C. L., Boardman, K. D., & Sather, M. R. (2002). Opioid dependence treatment, including buprenorphine/naloxone. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 36(2), 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell-Cunsolo, T. L., & Bellerose, M. (2021). Utilization of substance use treatment among criminal justice-involved individuals in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 125, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samples, H., Williams, A. R., Olfson, M., & Crystal, S. (2018). Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 95, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahler, G. J., Mennis, J., Stein, L. A. R., Belenko, S., Rohsenow, D. J., Grunwald, H. E., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., & Martin, R. A. (2022). Treatment outcomes associated with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) among criminal justice-referred admissions to residential treatment in the U.S., 2015–2018. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 236, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stata. (2017). Stata statistical software (Release 15). Stata Corp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Staton, M., Pike, E., Tillson, M., & Lofwall, M. R. (2023). Facilitating factors and barriers for use of medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) among justice-involved individuals in rural Appalachia. Journal of Community Psychology, 52(8), 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2021). Medications for opioid use disorder (Treatment Improvement Protocol [TIP] Series 63; No. PEP21-02-01-002). SAMHSA.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2024). Waiver elimination (MAT act). Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/substance-use/treatment/statutes-regulations-guidelines/mat-act (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Tangney, J. P., Folk, J. B., Graham, D. M., Stuewig, J. B., Blalock, D. V., Salatino, A., Blasko, B. L., & Moore, K. E. (2016). Changes in inmates’ substance use and dependence from pre-incarceration to one year post-release. Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timko, C., Schultz, N. R., Cucciare, M. A., Vittorio, L., & Garrison-Diehn, C. (2016). Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. Journal of Addiction Diseases, 35(1), 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA]. (2021). Suboxone (buprenorphine and naloxone) sublingual tablets: Label (prescribing information) [PDF]. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020733s007s008lbl.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Wakeman, S. E., Larochelle, M. R., Ameli, O., Chaisson, C. E., McPheeters, J. T., Crown, W. H., Azocar, F., & Sanghavi, D. M. (2020). Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Network Open, 3(2), e1920622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsco, A. J., Champagne-Langabeer, T., Holder, T. F., Stotts, A. L., & Langabeer, J. R. (2020a). Developing interagency collaboration to address the opioid epidemic: A scoping review of joint criminal justice and healthcare initiatives. International Journal of Drug Policy, 83, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsco, A. J., Garza, R. D., Champagne-Langabeer, T., & Langabeer, J. R. (2020b). Alternatives to arrest for illicit opioid use: A joint criminal justice and healthcare treatment collaboration. Substance Abuse Research and Treatment, 14, 1178221820953390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P., Tossone, K., Ashmead, R., Bickert, T., Bailey, E., Doogan, N. J., Mack, A., Schmidt, S., & Bonny, A. E. (2022). Examining differences in retention on medication for opioid use disorder: An analysis of Ohio medicaid data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 136, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics/Clinical Characteristic | Involved in the CJS N (%) | Not Involved in the CJS N (%) | Total N (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 91 (24.8) | 276 (75.2) | 367 (100) | NA |

| Age, mean (sd) | 33.8 (7.9) | 35.6 (10.2) | 35.2 (9.7) | 0.13 * |

| Gender (Sex assigned at birth) | 0.07 ** | |||

| Men | 57 (62.6) | 141 (51.6) | 198 (54.4) | |

| Woman | 34 (37.4) | 132 (48.4) | 166 (45.6) | |

| Race | 0.03 ** | |||

| White | 79 (87.8) | 198 (77.3) | 267 (80.1) | |

| Non-White | 11 (12.2) | 58 (22.7) | 69 (19.9) | |

| Housing | 0.89 ** | |||

| Own/rent apartment or home | 30 (33.0) | 95 (34.4) | 125 (34.1) | |

| Live with family or friends | 47 (51.6) | 144 (52.2) | 191 (52.0) | |

| Homeless or other | 14 (15.4) | 37 (13.4) | 51 (13.9) | |

| Insurance | 0.62 ** | |||

| No | 59 (64.8) | 169 (61.2) | 228 (62.1) | |

| Yes | 32 (55.2) | 107 (38.8) | 139 (37.9) | |

| Age at first use of substances, mean (sd) | 18.2 (6.4) | 21.1 (8.6) | 20.4 (8.2) | 0.007 * |

| History of use of IV drugs | 0.02 ** | |||

| No | 34 (41.5) | 148 (57.1) | 182 (53.4) | |

| Yes | 48 (58.5) | 111 (42.9) | 159 (46.6) | |

| Primary opioid taken was a prescription/pressed pills | 0.09 ** | |||

| No | 55 (60.4) | 138 (50.0) | 193 (52.6) | |

| Yes | 36 (39.6) | 138 (50.0) | 174 (47.4) | |

| Primary opioid taken was illicit | 0.01 ** | |||

| No | 20 (22.0) | 100 (36.2) | 120 (32.7) | |

| Yes | 71 (78.0) | 176 (63.8) | 247 (67.3) | |

| Type of primary opioid prescribed ^ | ||||

| Oxycodone | 27 (29.7) | 99 (35.9) | 126 (34.3) | 0.31 ** |

| Hydrocodone | 23 (25.3) | 80 (29.0) | 103 (28.1) | 0.59 ** |

| Codeine | 2 (2.2) | 9 (3.3) | 11 (3.0) | 0.99 ** |

| Morphine | 1 (1.1) | 6 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) | 0.99 ** |

| Buprenorphine | 2 (2.2) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.1) | 0.26 ** |

| Tramadol | 1 (1.1) | 6 (2.2) | 7 (1.9) | 0.99 ** |

| Methadone | 0 | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.1) | 0.58 ** |

| Hydromorphone | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0.99 ** |

| Type of primary illicit substances consumed ^ | ||||

| Heroin | 61 (67.0) | 134 (48.5) | 195 (53.1) | 0.002 ** |

| Fentanyl | 34 (37.4) | 77 (27.9) | 111 (30.2) | 0.11 ** |

| Other non-prescribed opioids | 2 (2.2) | 11 (4.0) | 13 (3.5) | 0.53 ** |

| Prior use of MOUD | 0.02 ** | |||

| Yes | 29 (31.9) | 127 (46.0) | 156 (42.5) | |

| No | 62 (68.1) | 149 (54.0) | 211 (57.5) | |

| Days on MOUD, median (IQR) | 97 (20–379) | 48 (7–320) | 61 (7–349) | 0.16 ^ |

| Total number of sessions served at the 90th day in program, median (IQR) | 12 (4–20) | 3 (0.5–8) | 5 (1–11) | ≤0.0001 *** |

| Characteristic | Total N (%) | Days in MOUD Median (IQR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 367 (100) | 61 (7–349) | NA |

| Involved in the CJS | 0.16 * | ||

| Yes | 91 (24.8) | 97 (20–379) | |

| No | 276 (75.2) | 48 (7–320) | |

| Age at entry to the program, mean (sd) | 35.2 (9.7) | 61 (7–349) | 0.16 ** |

| Housing | 0.05 * | ||

| Own/rent apartment or home | 125 (34.1) | 107 (19–424) | |

| Live with family or friends | 191 (52.0) | 39 (7–258) | |

| Homeless or other | 51 (13.9) | 119 (7–338) | |

| Age at first drug use, mean (sd) | 20.4 (8.2) | 61 (7–349) | 0.81 ** |

| History of use of IV drugs | 0.02 * | ||

| No | 182 (53.4) | 82 (11–419) | |

| Yes | 159 (46.6) | 35 (7–236) | |

| Primary opioid taken was a prescription | 0.04 * | ||

| No | 193 (52.6) | 39 (7–282) | |

| Yes | 174 (47.4) | 102 (14–418) | |

| Primary opioid taken was illegal | 0.03 * | ||

| No | 120 (32.7) | 120 (11–429) | |

| Yes | 247 (67.3) | 43 (7–274) | |

| Primary drug taken was other substance | 0.09 * | ||

| No | 275 (25.1) | 77 (7–386) | |

| Yes | 92 (74.9) | 32 (7–234) | |

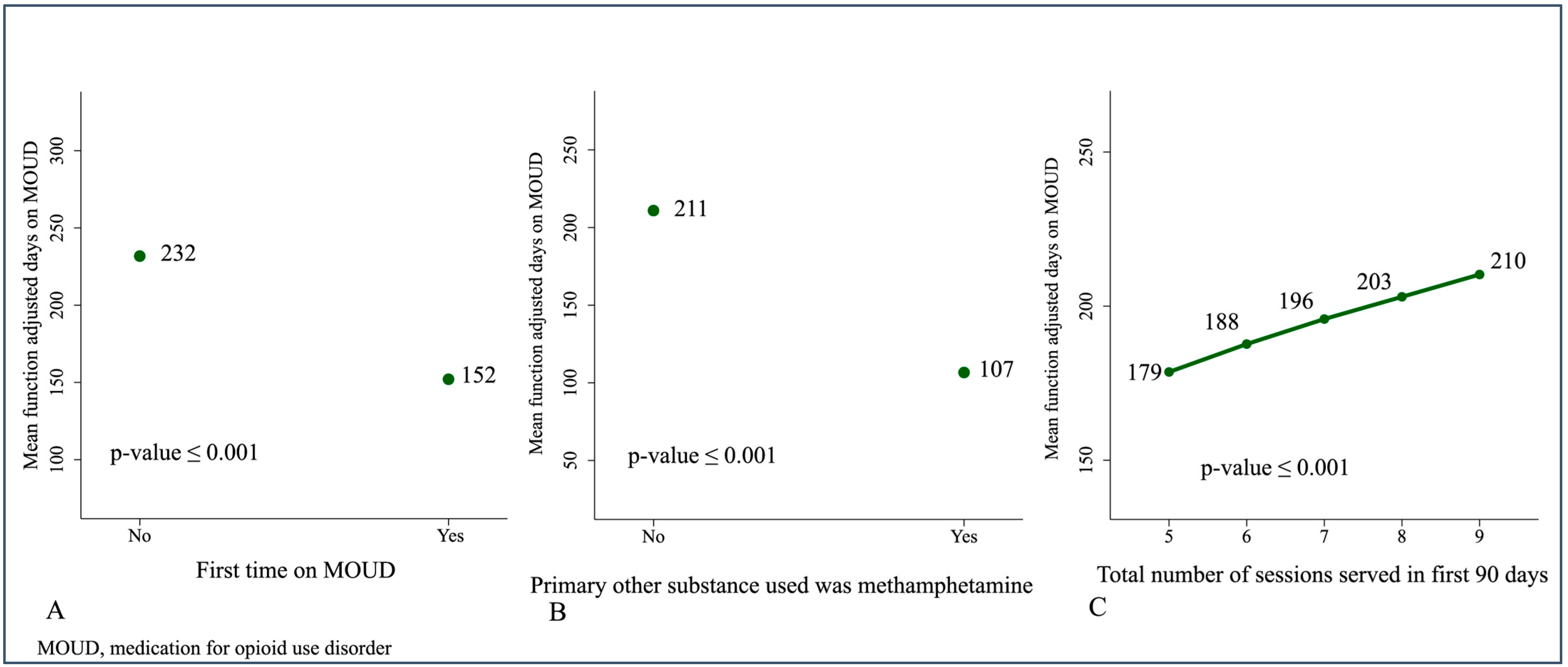

| First time on MOUD | 0.02 * | ||

| No | 211 (57.5) | 106 (14–419) | |

| Yes | 156 (42.5) | 42 (7–226) | |

| Overdosed | 0.17 * | ||

| Yes | 226 (38.4) | 49 (7–290) | |

| No | 141 (61.6) | 84 (8–419) | |

| Type of visit and MOUD prescription | 0.08 * | ||

| Visited and prescribed MOUD by MP | 343 (94.0) | 51 (7–355) | |

| Not visited the MP but prescribed | 22 (6.0) | 158 (76–338) | |

| Total sessions served in the first 90 days in the program, median (IQR) | 5 (1–12) | 97 (19–386) | 0.0001 ** |

| Characteristic | OR | Std. Error | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Women | Reference | |||

| Men | 1.52 | 0.45 | (0.85 to 2.72) | 0.16 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Non-White | 0.83 | 0.33 | (0.37 to 1.83) | 0.64 |

| Age at first drug use | 0.96 | 0.02 | (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Use of IV drugs | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.35 | (0.48 to 1.99) | 0.95 |

| Primary opioid taken was a prescription | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.63 | 0.23 | (0.31 to 1.30) | 0.21 |

| Type of primary illicit substance consumed was heroin | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.36 | 0.49 | (0.67 to 2.74) | 0.39 |

| First time on MOUD | ||||

| Yes | 0.68 | 0.21 | (0.36 to 1.26) | 0.22 |

| No | Reference | |||

| Total sessions served in the first 90 days in the program | ||||

| 1.1 | 0.02 | (1.07 to 1.14) | ≤0.001 |

| Observed Estimate | 95% CI | Bootstrap Std. Error | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted mean of the days on MOUD | 201.38 | (172.22 to 233.52) | 15.25 | ≤0.001 |

| Covariates effects | ||||

| Involved in the CJS vs. not involved | −53.83 | (−121.16 to 16.08) | 36.27 | 0.14 |

| Housing | ||||

| Living with family or friends vs. Own/rent apartment or house | −51.48 | (−97.48 to −2.50) | 24.52 | 0.04 |

| Homeless or other vs. Own/rent apartment or house | −71.58 | (−156.60 to 10.65) | 43.08 | 0.1 |

| History of use of IV drugs | −79.63 | (−135.21 to −17.74) | 30.28 | 0.009 |

| Primary opioid taken was prescription | −45.51 | (−125.27 to 30.99) | 38.82 | 0.24 |

| First time on MOUD | −79.72 | (−138.40 to −27.21) | 28.74 | 0.006 |

| Total sessions served in the first 90 days in the program | 10.81 | (5.55 to 15.67) | 2.64 | 0.001 |

| Primary opioid prescribed was hydrocodone vs. not | 63.44 | (−13.22 to 144.88) | 40.43 | 0.12 |

| Primary other substance consumed was methamphetamine vs. not | −104.21 | (−165.03 to −45.73) | 30.43 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yatsco, A.; Vega, F.R.; Cohen, A.S.; Cardenas-Turanzas, M.; Langabeer, J.R.; Champagne-Langabeer, T. Retention on Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder in Justice-Involved Individuals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010122

Yatsco A, Vega FR, Cohen AS, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Langabeer JR, Champagne-Langabeer T. Retention on Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder in Justice-Involved Individuals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleYatsco, Andrea, Francine R. Vega, Audrey Sarah Cohen, Marylou Cardenas-Turanzas, James R. Langabeer, and Tiffany Champagne-Langabeer. 2026. "Retention on Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder in Justice-Involved Individuals: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010122

APA StyleYatsco, A., Vega, F. R., Cohen, A. S., Cardenas-Turanzas, M., Langabeer, J. R., & Champagne-Langabeer, T. (2026). Retention on Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder in Justice-Involved Individuals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010122