Self-Evaluation Dimensions of Criminal Activity and Prospects Simulation of Persons Serving Custodial Sentence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

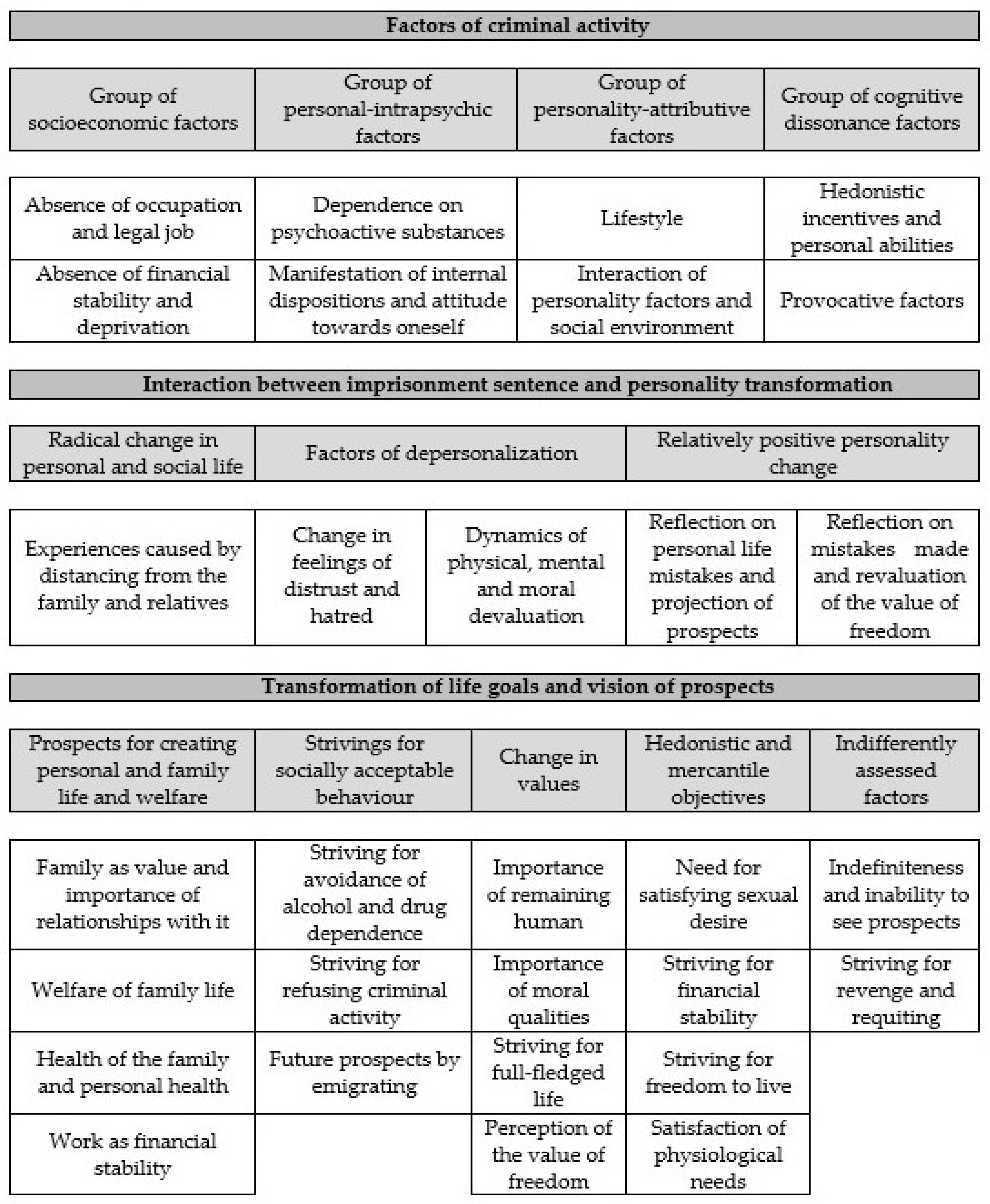

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galambos, N.L.; MacDonald, S.W.S.; Naphtali, C.; Cohen, A.; de Frias, C.M. Cognitive Performance Differentiates Selected Aspects of Psychosocial Maturity in Adolescence. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2005, 28, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, N.L.; Tilton-Weaver, L.C. Adolescents’ Psychosocial Maturity, Problem Behavior, and Subjective Age: In Search of the Adulthood. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2000, 4, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M. 21st Century Criminology: A Reference Handbook; Thousand SAGE Publications Inc.: Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dombeck, M. Robert Kegan’s Awesome Theory of Social Maturity. 2007. Available online: https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/robert-kegan-s-awesome-theory-of-social-maturity/ (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Žemaitytė, I.; Čiurinskienė, D. Nuteistųjų požiūris į dalyvavimą socialinėse programose kaip resocializacijos galimybę. Soc. Darb. 2004, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Vaičiūnienė, R.; Viršilas, V. Laisvės Atėmimo Vietose Taikomų Socialinės Reabilitacijos Priemonių Sistemos Analizė, Probleminiai Taikymo Aspektai: Mokslo Studija; Lietuvos Teisės Institutas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, M.; Campbell, O.; Demby, B.; Ferranti, S.M.; Santos, M. Doing Prison Research: Views from Inside. Qual. Inq. 2005, 11, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić-Ćatić, M. Challenges in Conducting Prison Research. Crim. Justice Issues 2011, 11, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L.; Indermaur, D. The Ethics of Research with Prisoners. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2007, 19, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörg, P. Ethics in research involving prisoners. Int. J. Prison. Health 2008, 4, 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakutytė, R.; Geležinienė, R.; Gumuliauskienė, A.; Juodraitis, A.; Jurevičienė, M.; Šapelytė, O. Socializacijos Centro Veiklos Modeliavimas: Ugdytinių Resocializacijos Procesų Valdymas ir Metodika: Mokslo Studija; BMK Leidykla: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Samašonok, K.; Gudonis, V.; Juodraitis, A. Institucinio Ugdymo ir Adaptyvaus Elgesio Dermės Modeliavimas: Monografija; Šiaulių Universiteto Leidykla: Šiauliai, Lithuania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bubnys, R. A Journey of Self-Reflection in Students’ Perception of Practice and Roles in the Profession. Sustainability 2019, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žydžiūnaitė, V.; Stepanavičienė, R.; Bubnys, R. Artimųjų Išgyvenimai Prižiūrint Alzheimerio Liga Sergantį Asmenį: Socialinio Darbo Kontekstas: Mokslo studija; Šiaulių Kolegijos Leidybos Centras: Šiauliai, Lithuania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alifanovienė, D.; Šapelytė, O.; Gerulaitis, D. The Analysis of Contexts of the Coping with the Stress Experienced by Social Welfare Professionals: Experience of Lithuania and Scandinavian Countries. Soc. Welf. Interdiscip. Approach 2017, 7, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alifanovienė, D.; Šapelytė, O.; Kryukova, T. Reconstruction of social, cultural and educational environment in the context of professional stress factors: Subjective experiences of social pedagogues. Soc. Welf. Interdiscip. Approach 2016, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J. On the pragmatics of Qualitative Assessment: Designing the Process for Content Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 22, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Resour. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, D. Confronting the Disabling Effects of Imprisonment: Toward Prehabilitation. Soc. Justice 2018, 45, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, T.; Topalli, V. Criminal Self-Efficacy: Exploring the Correlates and Consequences of a “Successful Criminal” Identity. Crim. Justice Behav. 2012, 39, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernkhahn, K. Research on Long Term Imprisonment. In Long-Term Imprisonment and Human Rights; Drenkhahn, K., Dudeck, M., Dünkel, F., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin, D.S.; Cullen, F.T.; Jonson, C.L. Imprisonment and Reoffending. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research; Tonry, M., Ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; Volume 38, pp. 115–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, D. How Much Does Imprisonment Protect the Community Through Incapacitation? In Sentencing Advisory Council; Sentencing Advisory Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sakalauskas, G. Kalinimo sąlygos ir kalinių resocializacijos prielaidos. Teisės Probl. 2015, 2, 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry, T.P. Developmental Theories of Crime and Delinquency; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero, A.R.; Farrington, D.P.; Blumstein, A. Cambridge Studies in Criminology. In Key Issues in Criminal Career Research: New Analyses of the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, W.H.J. Emotional Capacities and Sensitivity in Psychopaths. 2003. Available online: http://www.goertzel.org/dynapsyc/2003/psychopaths.htm (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Baumeister, R.F. Ego Depletion and Self-Control Failure: An Energy Model of the Self’s Executive Function. Self Identity 2002, 1, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, E.; Steinberg, L. Maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents May be Less Capable than Adults. Behav. Sci. Law 2000, 18, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecca, L.; Winder, B.; Norman, C.; Banyard, P. A Life Sentence in Installments: A Qualitative Analysis of Repeat Offending Among Short-Sentenced Offenders. Vict. Offenders 2018, 13, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C.; Blagden, N. Accumulating meaning, purpose and opportunities to change ‘drip by drip’: The impact of being a listener in prison. Psychol. Crime Law 2014, 20, 902–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, D.; Canter, D.V. Narrative roles in criminal action: An integrative framework for differentiating offenders. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2012, 17, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, C.J.N. Existing but not Living: Neo-Civil Death and the Carceral State; CUNY Academic Works. 2014. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/283 (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Wacquant, L. From slavery to mass incarceration. New Left Rev. 2002, 13, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the European Prison Rules. 2006. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/human-rights-rule-of-law/european-prison-rules (accessed on 12 March 2019).

| Category | Subcategory | Proving Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Financial problems and absence of occupation | Limitations of occupation and legal job opportunities | Unemployment, lack of occupation… (I1); … I can’t work legally… (I42) |

| Financial problems and deprivation in the family | Lack of money (I28); Shortage of money, problems… (I33); Financial difficulties (I11); Absence of constant income (R41); Lack of money, bailiffs take away as much as half of the salary and nothing is left for living (I42); … of course financial shortages, deprivation in the family (I56) | |

| Consequences of dependence | Consequences of substance abuse and dependence | Alcohol (I1); (I6); (I4); (I7); (I14); (I15); (I25); (I26); (I28); (I31); (I32); (I36); … alcohol use had a big influence (I45); It was determined only by alcohol and that’s it (I46); Most often criminal activity was determined by alcohol (I56) |

| Drug dependence (I21); Drugs… (I26); Drug withdrawal (I44); My criminal activity was caused by the use of drugs (I50) | ||

| Factors of the personality and social environment | Factors of lifestyle | The way… (I18); and the way of life in the beginning… (I20); Immoral life… (I4); Absence of a specific goal of life (I52); I became disappointed with life… (I50) |

| Consequences determined by external environment | … inappropriate friends (I6); Friends’ actions (I40); A bad company (I22); Inappropriate company, “fool type acquaintances” (I27); … communication circle… (I28); inappropriate company… (I35); Friends (I49); inappropriate friends (I56); Actions of other people (I17); I got acquainted professedly with a friend and here, drugs, thefts drowned me to hell… (I50) | |

| People liars, who are saving themselves and write off their crimes on others (I16); I cannot state that the influence of others, because I was not driven by violence. But otherwise, I think, it’s the environment (I9) | ||

| Consequences determined by inner qualities and self-esteem | My character… pride of myself (I2); I was disappointed… and in myself (I50) | |

| I think the criminal activity was caused by my excessive trust in people, due to which I was engaged, and later I was threatened so that I continue that activity (I53) | ||

| Lack of responsibility… (I45); being under the influence, we behaved completely irresponsibly (I48) | ||

| Consequences of abilities to manage and predict the situation | Desire to easily become rich (I5); … inability to resist easy money (I49) | |

| … no thinking about possible consequences (I8) | ||

| … inability to evaluate and manage the conflict situation (I58) | ||

| Consequences of provocative factors | Permission to provoke oneself (I58); … provocation of the aggrieved person (I3); … I submitted to provocation (I7); Provocation… (I24) |

| Category | Subcategory | Proving Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Group of factors of perceiving radical change in personal life | Constant experiencing of the feeling of loss of close people and lack of close relationships | Distances from the family (I2); It’s hard to be without family members… (I5); … what affects me most is the lack of family (I9); Personally me, it affects even very strongly, affects psychologically, I am constantly thinking about the family (I11) |

| Psychologically this affected very strongly because I can’t communicate with my family, take care of others, be a support for my spouse, I can’t raise our daughter together (I53) | ||

| Group of factors determining personality change | Loss of confidence in oneself and the environment | Very bad, you become nervous, lose trust in people (I3); Of course, bad, I became nervous… (I33); This makes me personally nervous (I46) |

| In most cases, an imprisoned person loses self-confidence and goes towards destruction (I9); This is ruining me, doesn’t give self-confidence… (I22) | ||

| Negatively, and raises hatred and distrust in people inside (I21); The system of imprisonment tortures, punishes a person, makes him evil, distrustful of the society (I57) | ||

| I was forced to give thought to a lot of things, to think over a lot what I was doing wrong. It ruins, because sometimes they imprison without finding out all the truth, therefore, cause the feeling of distrust in justice, but at the same time, having gone through this, the person strengthens, others break, you need to have a lot of will to pass this road (I4) | ||

| Change in physical, mental and moral aspects of the personality | It badly affects mentally and morally and slightly physically (I27); Not to mention the bodily illnesses, his inner world is ruined. Psyche gets warped (I48); Psychologically, physically, spiritually ruins while you are under arrest (I49) | |

| The mental state worsened, you become more aggressive (I41) Ruins you–turns you into a fool (I32); Ruins, tortures psychologically (I40); Imprisonment ruins me, I don’t feel stable (I50) | ||

| Imprisonment destroys a person both psychologically and physically, in such conditions diminishes dignity, tortures a person (I16); Imprisonment affects me mentally and morally (I35); Conditions traumatize (I24) | ||

| Group of factors of relatively positively assessed personality change | Rethinking of personal life | Allow to give thought how and where you live (I1); Allow to understand further life (I6) |

| There is a lot to think about when you temporarily lose your close people, even family, children. I try not to get stressed, I put good ideas for the future (I7) | ||

| Dynamics of reflection on mistakes made and revaluation of the value of freedom | Partially it affects in a good way because there is a lot of time to reflect on the bad things I have done and whether they will allow to correct them (I14); Give time to think about the mistakes made (I52) | |

| Imprisonment allows to understand that freedom is priceless. Also gives you the opportunity to read many interesting books, because there is no time for that in freedom (I13) | ||

| Makes you give thought, value life differently, helps to understand what freedom really is and what its price is (I45) | ||

| When you appear here, you think over what the person loses, that people don’t value freedom, because one reckless action and you give yourself and your family (I8) |

| Category | Subcategory | Proving Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of the meaning of personal and family life | Emphasis on the importance of the family and relationship with them | The most important is family (I2); (I4); (I5); (I6); (I8); (I14); (I15); (I19); (I20); (I24); (I25); (I26); (I29); (I36); (I39); (I44); (I49); For me in life the most important is family (I11); (I12); (I53) (I55); In my life, my family is the most important and it will always be so (I16); My children–my family, relationships with them (I21) |

| Exaltation of the family as an essential personal value | The most important thing in my life is my family, and without the family I would be nothing! Family is your people who you trust, when it is difficult for you, they will always help you, you can lean on them, they support you whatever you are! And of course, there would be no love—there would be no love in the world (I56); … to stick together, a harmonious family, to be together again (I7) | |

| Family, life, children, etc. (I34); Family, relatives, friends… (I35); Family, relatives… (I57); Family, children, relatives (I58); close people (I45); The most important thing for me is the family, my girlfriend and our children (I46); Family members, parents, brothers and all others (I30); The most important thing is family and children (I33); Family, parents (I41); Family, children, wife and all loving me (I9) | ||

| Emphasis on health of the family and personal health | … health (I20); Health of the family (I27); Most importantly, so that there is health (I28); … health of the family (I37); (I35) (I29); | |

| Group of factors of change in values | Importance of remaining human | The most important thing is to remain human (I13); and to remain human (I4); The most important thing is to be human (I23); |

| Value of freedom | The most important is freedom (I38); (I40); (I47); (I18); What I didn’t value before is freedom… (I4) | |

| Full-fledged life | Life itself!!! (I22); To live a complete, normal life (I3) | |

| Emphasis on understanding, peacefulness and love | … inner peace (I44); … love… (I47); mutual understanding (I57) | |

| The importance of moral qualities | One’s dignity, honour, honesty, emotional state, the ability to communicate, responsibility, the ability to think positively (I49) | |

| Life objectives grounded on material benefit and pleasure | The need for a woman | Beloved woman (I31); I want to have a lot of women (I32) |

| Striving for financial stability | Most importantly money (I42); … money (I47); financial stability (I44) | |

| Striving for freedom to live | To live in freedom, not only in Lithuania (I54) | |

| Importance of fulfilling physiological needs | The most important thing is not to be nervous and eat well (I43); To eat, do something, also listen to some radio (I52) |

| Category | Subcategory | Proving Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Group of factors of creating personal and family life and welfare | (Re-)creation of family life and striving for its welfare | … to create life, to create a family (I35); To create a family (I2); To get out of here, create a family… (I4); to create a family (I39); With family and relatives (I26) |

| Be with one’s family every second, because only when you are imprisoned you can understand that every moment is important and so precious (I53); To start standing up on one’s feet upon return to the family […] and do everything for the sake of the family and live a beautiful life (I9) | ||

| To live family life (I6); Plans upon going to freedom […] to create a successful family further (I7); to take care of the family (I8); And to spend as much time as possible with the family (I5); Calm life with the family (I25) | ||

| To live peacefully with my beloved woman (I31) | ||

| … to live morally and never separate from children (I33); To take care and enjoy children… (I58); To have a nice family and many kids (I18) | ||

| Group of occupational-professional activity objectives | Striving for work as financial stability of the family | … to find a job […] to provide a family (I4); To stand up firmly on one’s feet, find a good job so that the family is not short of anything (I11); To work as much as possible and earn… (I5) |

| Professional activity as striving for the opportunity of career and adaptation | … I would like to find a job (I7); to restore and continue working activities (I58); to continue working… (I38) Upon release from prison I plan to start working… (I33) I plan to continue working and make a career (I35); After leaving to go to work […] to adapt first of all (I8) | |

| Group of factors of simulating socially acceptable behaviour | Striving for avoidance of alcohol and drug dependence | not to abuse alcohol… (I7); Not to abuse alcohol and stop making such crimes (I46); to attend alcoholics anonymous meetings and to try to live morally (I4); I plan to stop wasting time and to look at life only soberly (I19); Rehabilitation–to stop using drugs… (I44) |

| Striving for a full-fledged life by refusing criminal activity | Full-fledged life as I lived (I24); To live a decent life (I41) | |

| To start everything anew, forget the past, change life comprehensively (I45); To serve the sentence I was given and stop getting entangled in crimes (I30); … no longer make such crimes (I46) | ||

| Group of factors of simulating migration plans | Striving for future prospects by emigrating | I plan to live my further life with my family, but not in Lithuania of course (I16); To work, build a better life, create a family, leave Lithuania (I49) |

| To emigrate (R54); … foreign countries–work, to create a family. Everything after release, of course (R44) | ||

| To depart from Lithuania, at the same time I’ll change my environment and the circle of friends (I50) | ||

| My plans are really realistic. Upon release, I plan to go abroad to my mother. She has been waiting for me long and I plan to find a job there and be a good person. Create my own family, buy my own dwelling and be happy, not to return to places of imprisonment (I56) | ||

| Group of factors of difficult-to-identify life prospects | Dominance of indefinite life prospects | All plans fell apart (I15); I don’t know myself (I23); First you need to become free, and further, we will see (I43); I don’t plan, everything will depend on circumstances (I3) |

| Since I am already 64, there is no need, aim or sense of planning anything in further life. And as to the next 10 years that I’ll have to spend in the imprisonment institution, there can’t be any thought about any planning. I’ll have to follow a completely alien, forced but probably necessary regime. There is no use of speaking that somebody will re-educate me, put me on the “right way” or change my character somehow otherwise. Although I am of retirement age, I may be able to do some work. Maybe I will attend some courses. But it’s just from curiosity, not necessity (I48) | ||

| The less you plan your life, the less stress you experience (I51) | ||

| Striving for revenge and requiting | To requite everyone for what they have deserved. Despite anything!!! (I52) | |

| I will serve a 20-year sentence. When I’m released, I’ll beat somebody to death with a hammer and come back to die in prison (I47) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juodraitis, A.; Bubnys, R.; Šapelytė, O. Self-Evaluation Dimensions of Criminal Activity and Prospects Simulation of Persons Serving Custodial Sentence. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070075

Juodraitis A, Bubnys R, Šapelytė O. Self-Evaluation Dimensions of Criminal Activity and Prospects Simulation of Persons Serving Custodial Sentence. Behavioral Sciences. 2019; 9(7):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070075

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuodraitis, Adolfas, Remigijus Bubnys, and Odeta Šapelytė. 2019. "Self-Evaluation Dimensions of Criminal Activity and Prospects Simulation of Persons Serving Custodial Sentence" Behavioral Sciences 9, no. 7: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070075

APA StyleJuodraitis, A., Bubnys, R., & Šapelytė, O. (2019). Self-Evaluation Dimensions of Criminal Activity and Prospects Simulation of Persons Serving Custodial Sentence. Behavioral Sciences, 9(7), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070075