Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

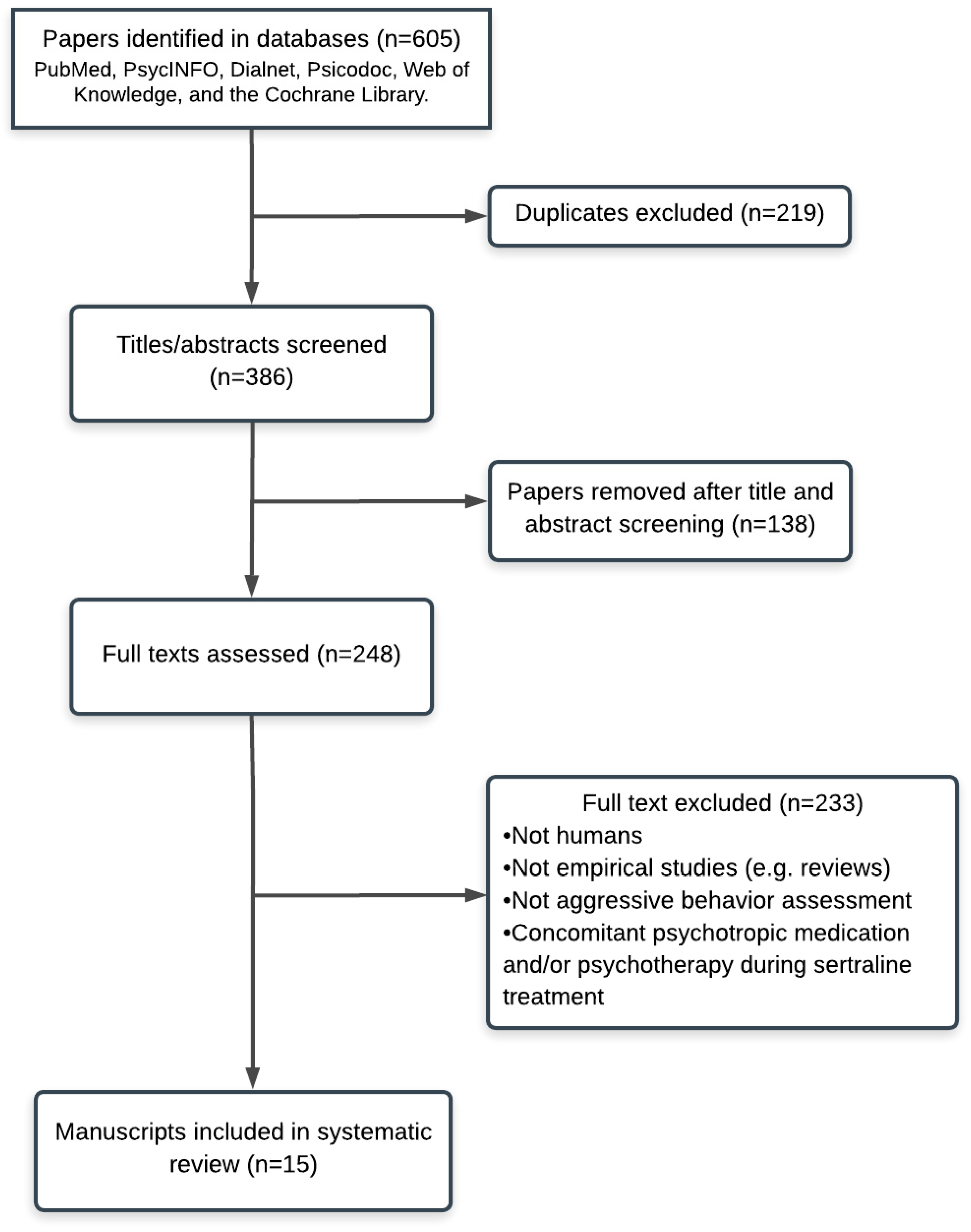

2. Search Strategy

3. Results

4. Case Reports

5. Open-Label, Uncontrolled Clinical Trials

6. Randomized Controlled Trials

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coccaro, E.F.; Fanning, J.R.; Phan, K.L.; Lee, R. Serotonin and impulsive aggression. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, A.R. The role of serotonin in impulsive aggression, suicide, and homicide in adolescents and adults: A literature review. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2015, 27, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Valtorta, F.; Comai, S. Serotonin dysfunction, aggressive behavior, and mental illness: Exploring the link using a dimensional approach. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.R.; Melloni, R.H. The role of serotonin, vasopressin, and serotonin/vasopressin interactions in aggressive behavior. In Neuroscience of Aggression; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 189–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bouvy, P.F.; Liem, M. Antidepressants and lethal violence in the Netherlands 1994–2008. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012, 222, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walsh, M.T.; Dinan, T.G. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and violence: A review of the available evidence. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001, 104, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielefeldt, A.Ø.; Danborg, P.B.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Precursors to suicidality and violence on antidepressants: Systematic review of trials in adult healthy volunteers. J. R. Soc. Med. 2016, 109, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, Y.; Lichtenstein, P.; Zetterqvist, J.; Gumpert, C.H.; Fazel, S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and violent crime: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguglia, E.; Casacchia, M.; Cassano, G.; Faravelli, C.; Ferrari, G.; Giordano, P.; Pancheri, P.; Ravizza, L.; Trabucchi, M.; Bolino, F.; et al. Double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of sertraline versus fluoxetine in major depression. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993, 8, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.; Kent, T.A.; Bryant, S.G. Postmarketing surveillance by patient self-monitoring: Preliminary data for sertraline versus fluoxetine. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1995, 56, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, G.; Born, L.; Steiner, M. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: Its profile and use in psychiatric disorders. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnie-Filali, O.; Abrial, E.; Lambás-Señas, L.; Haddjeri, N. Long-Term Adaptive Changes Induced by Antidepressants: From Conventional to Novel Therapies. In Mood Disorders; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, D.; McTavish, D. Sertraline. A Review of its Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Properties, and Therapeutic Potential in Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Drugs 1992, 44, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Moles, J.K.; Hawley, J.M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for aggressive behavior in patients with dementia after head injury. Pharmacotherapy 2001, 21, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneser, J.M.; Jox, R.J.; Borasio, G.D. Inappropriate sexual behaviour in a case of ALS and FTD: Successful treatment with sertraline. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2007, 8, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feder, R. Treatment of intermittent explosive disorder with sertraline in 3 patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnam, A.; MehrAra, A.; Dadashzadeh, H.; Chalabianlou, G.; Safikhanlou, S. Studying the Effect of Sertraline in Reducing Aggressive Behavior in Patients with Major Depression. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kant, R.; Smith-Seemiller, L.; Zeiler, D. Treatment of aggression and irritability after head injury. Brain Inj. 1998, 12, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoussi, R.J.; Liu, J.; Coccaro, E.F. An open trial of sertraline in personality disordered patients with impulsive aggression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, T.; Schofield, P.W.; Greenberg, D.; Allnutt, S.H.; Indig, D.; Carr, V.; D’Este, C.; Mitchell, P.B.; Knight, L.; Ellis, A. Reducing impulsivity in repeat violent offenders: An open label trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingard, R.J.; Zimnitzky, B.; DeMaso, D.R.; Bauman, M.L.; Bucci, J.P. Sertraline treatment of transition-associated anxiety and agitation in children with autistic disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 1997, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Quitkin, F.M.; Zisook, S.; Pearlstein, T.; Stone, A.; Rosenbaum, J.F. A preliminary study on the efficacy of sertraline and imipramine on anger attacks in atypical depression and dysthymia. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1997, 33, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fann, J.R.; Uomoto, J.M.; Katon, W.J. Sertraline in the treatment of major depression following mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 12, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fann, J.R.; Bombardier, C.H.; Temkin, N.; Esselman, P.; Warms, C.; Barber, J.; Dikmen, S. Sertraline for Major Depression During the Year Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017, 32, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkers, K.A.; Halbreich, U.; Freeman, E.; Brown, C.; Endicott, J.; Frank, E.; Parry, B.; Pearlstein, T.; Severino, S.; Stout, A.; et al. Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment. A randomized controlled trial. Sertraline Premenstrual Dysphoric Collaborative Study Group. JAMA 1997, 278, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonkers, K.A.; Kornstein, S.G.; Gueorguieva, R.; Merry, B.; Van Steenburgh, K.; Altemus, M. Symptom-Onset Dosing of Sertraline for the Treatment of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.R.; Landerman, L.R.; Farfel, G.M.; Clary, C.M. Characterizing the effects of sertraline in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.; Landerman, L.R.; Clary, C.M. Improvement of anger at one week predicts the effects of sertraline and placebo in PTSD. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 38, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.L.; Levin-Silton, R.; Sass, S.M.; Heller, W.; Miller, G.A. Anger style, psychopathology, and regional brain activity. Emotion 2008, 8, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Kim, M.; Akutsu, S.; Oshio, A. Effects of anger regulation and social anxiety on perceived stress. Health Psychol. Open 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mook, J.; Van Der Ploeg, H.M.; Kleijn, W.C. Anxiety, anger and depression: Relationships at the trait level. Anxiety Res. 1990, 3, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Sample | Age | Gender | Education (Years) | SSRI (Sertraline) Dosage Range and Time | Onset Sertraline Effects | Current Drug Misuse | Violent Behavior Assessment and Changes | Side-Effects Related Aggressive Behavior | Side-Effects Not Directly Related to Aggressive Behavior | Funding Source |

| Case Reports | |||||||||||

| Kim et al. [16] | Multiple closed head injuries (n = 1), no comparison group. | 58 | ♂ | – | From 50 to 100 mg/day for unknown period | 10 days | No | Family report. Reduction in aggressive outbursts. | - | - | - |

| Anneser et al. [17] | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with frontotemporal dementia and inappropriate sexual behavior (n = 1), no comparison group. | 53 | ♂ | – | 100 mg/day for unknown period | – | No | Wife’s report. Reduction in aggressive outbursts. | – | – | HWP fellowship from the University of Munich |

| Feder et al. [18] | Treatment of intermittent explosive disorder with sertraline in 3 patients, no comparison group. | 51 30 29 | ♂ ♀ ♂ | 50 mg 50 mg 50–100 mg | 18 months (appeared week 2) 24 months (appeared week 6) 5 months (appeared after 6 weeks | No | Own and wife’s/husband’s report (three cases). | No | No | – | |

| Open Clinical | |||||||||||

| Farnam et al. [19] | Depression (n = 23), no comparison group. Pre-post design. | 33.91 ± 14.80 | ♂ and ♀ (unknown gender distribution) | – | From 50 to 100 mg/day for 8 weeks | 8 weeks | – | State Trait Anger Expression Inventory: Reductions in anger-state and anger control-in and -out. Absence of trait anger. | Yes | – | – |

| Kant et al. [20] | Closed head injury (n = 13), no comparison group. Pre-post design. | 37.6 | 77% ♂ 23% ♀ | – | From 50 to 200 mg/day for 8 weeks | 4 weeks | No | Anger Irritability Assault Questionnaire: Significant reduction in irritability and aggressive outbursts. | - | - | Educational grant from Pfizer, Inc. |

| Kavoussi et al. [21] | Personality disorders (n = 11, only 7 completed), no comparison group. Pre-post design. | From 20 to 53 | 64% ♂ 36% ♀ | – | From 50 to 200 mg/day for 8 weeks | From 2 to 4 weeks | No | Overt Aggression Scale: Reductions in overt aggression and irritability. | Yes | – | – |

| Butler et al. [22] | Violent and impulsive offenders (n = 34, only 20 completed) no comparison group. Pre-post design. | 36.5 ± 11.9 | ♂ | 15.3 ± 1.7 years | 25 mg sertraline (day 1), then 50 mg (day 2), and 100 mg (day 3) for 3 months | 4 weeks | No | Anger Irritability and Assault Questionnaire: Reductions in the following aspects related to violence: impulsivity (35%), irritability (45%), anger (63%), assault (51%), verbal-assault (40%), and indirect-assault (63%) | – | Yes (9%) | – |

| Steingard et al. [23] | Autism spectrum disorders (n = 9) | From 6 to 12 | 67% ♂ 33% ♀ | – | From 25 to 100 mg/day for 1 year | From 2 to 8 weeks | No | Parents’ report | Yes (25%) | – | – |

| Randomized Controlled Trials (Multicenter, Double-Blind and Placebo Group) | |||||||||||

| Fava et al. [24] | Patients with atypical major depression or dysthymia (n = 53) Three groups: Sertraline (n = 56) Imipramine (n = 52) Placebo (n = 60) Pre-post design. | – | – | – | Up to 200 mg/day for 12 weeks | 12 weeks | – | Anger Attacks Questionnaire: 53% of participants reported a reduction in anger attacks in the sertraline group, 57% in the imipramine group, and 37% in the placebo group | Yes (7.7%) | – | Partly funded by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals |

| Fann et al. [25] | Major depression after mild closed traumatic brain injury (n = 15). Participants received a week of placebo treatment, without specifying the exact moment, plus 8 weeks of sertraline treatment. Pre-post design. | 41.9 ± 8.5 | 46.7% ♂ 53.3% ♀ | 15.1 ± 3.4 years | First week: 25 mg/day Second week: 25–50 mg/day Third week: 25–100 mg/day From 4th to 8th week: 25–200 mg/day | 8 weeks | 53% of the sample presented lifetime alcohol or drug abuse | Brief Anger and Aggression Questionnaire: Decreases in averages scores in all samples after sertraline treatment. | – | – | Educational grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals |

| Fann et al. [26] | Major depression after mild closed traumatic brain injury (n = 53). Two groups: sertraline (n = 24) and placebo (n = 29). Pre-post design. | 37.5 ± 12.5 | 74% ♂ 26% ♀ | 23% did not complete high school and 77% had completed it. | Medication was started at 25–50 mg every morning. This dose increased 50 mg daily to a maximum dose of 200 mg for 8–10 weeks. | 12 weeks | 69% presented a history of alcohol and/or drug dependence | Brief Anger and Aggression Questionnaire: Both groups (sertraline and placebo) presented decreases in anger levels, but there were no differences between groups. In fact, there were differences between treatment responders and non-responders. | Yes (7%) | Yes (33%) | The National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Institutes of Health grant R01HD39415. Pfizer supplied sertraline and placebo |

| Yonkers et al. [27] | Women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (n = 121). Two groups: sertraline and placebo group. Pre-post design. | 36.8 ± 4.8 | ♀ | – | Three cycles during luteal phase: First: 50 mg/day Second: 50–100 mg/day (not enough response) Third: 50–150 mg/day | 1 week | – | Daily Record of Severity of Problems: Significant improvements and reductions in anger and irritability for sertraline in comparison with the control group. | – | – | Pfizer Ine, New York, NY. |

| Yonkers et al. [28] | Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (n = 125) Two groups: sertraline and placebo group. Pre-post design. | 33.7 | ♀ | 58% college studies and 32% some college | From 50 to 100 mg/day when premenstrual symptoms appeared | 1 week | – | Premenstrual Tension Scale: Significant improvements and reductions in anger and irritability for sertraline in comparison with the control group. | – | – | Grants R01 MH072955, 1R01 MH072645 (Dr Kornstein), R01 MH072962, from the National Institute of Mental Health. UL1 TR000457 (Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Pfizer supplied sertraline and placebo |

| Davidson et al. [29] | TEPT patients (n = 191) Two groups: sertraline and placebo group. Pre-post design. | From 18 to 65 | ♂ and ♀ (unknown gender distribution) | – | From 25 to 200 mg/day for 12 weeks | 1 week | No | Davidson Trauma Scale (frequency and severity of anger): Greater response and mood improvements after sertraline treatment | – | – | Grant from Pfizer Inc. and NIMH grant 1R01 MH 56656 01A |

| Davidson et al. [30] | TEPT (n = 173) Two groups: sertraline and placebo group. Pre-post design. | From 18 to 65 | ♂ and ♀ (unknown) | – | From 25 to 200 mg/day for 12 weeks | – | No | Davidson Trauma Scale (frequency and severity anger): Greater response and mood improvements after sertraline treatment | – | – | Partly funded by Pfizer Inc. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Martínez, Á.; Murciano-Martí, S.; Moya-Albiol, L. Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050057

Romero-Martínez Á, Murciano-Martí S, Moya-Albiol L. Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2019; 9(5):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050057

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Martínez, Ángel, Sonia Murciano-Martí, and Luis Moya-Albiol. 2019. "Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 9, no. 5: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050057

APA StyleRomero-Martínez, Á., Murciano-Martí, S., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2019). Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 9(5), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9050057