Interaction Diagrams: Development of a Method for Observing Group Interactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. What Needs to Be Recorded?

1.2. Tools for Recording

1.3. Sociogram

1.4. Summary

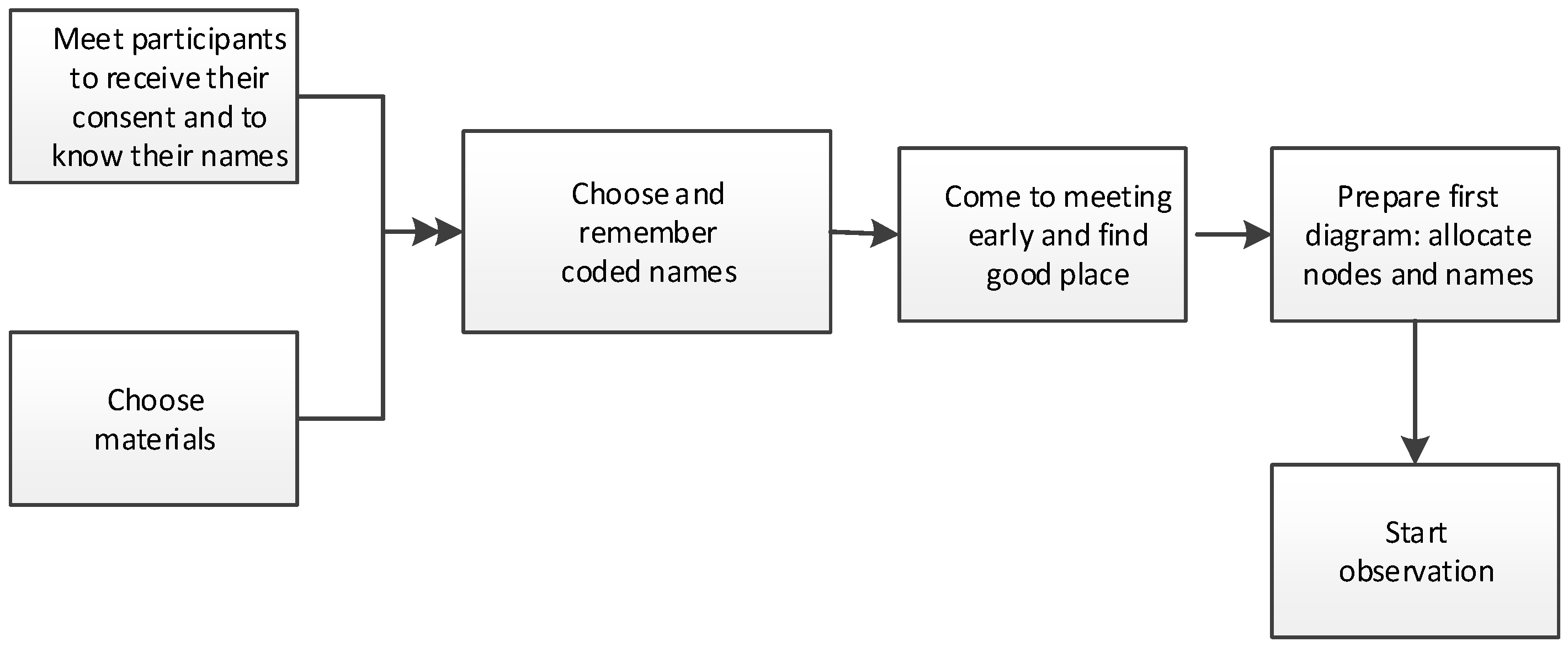

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

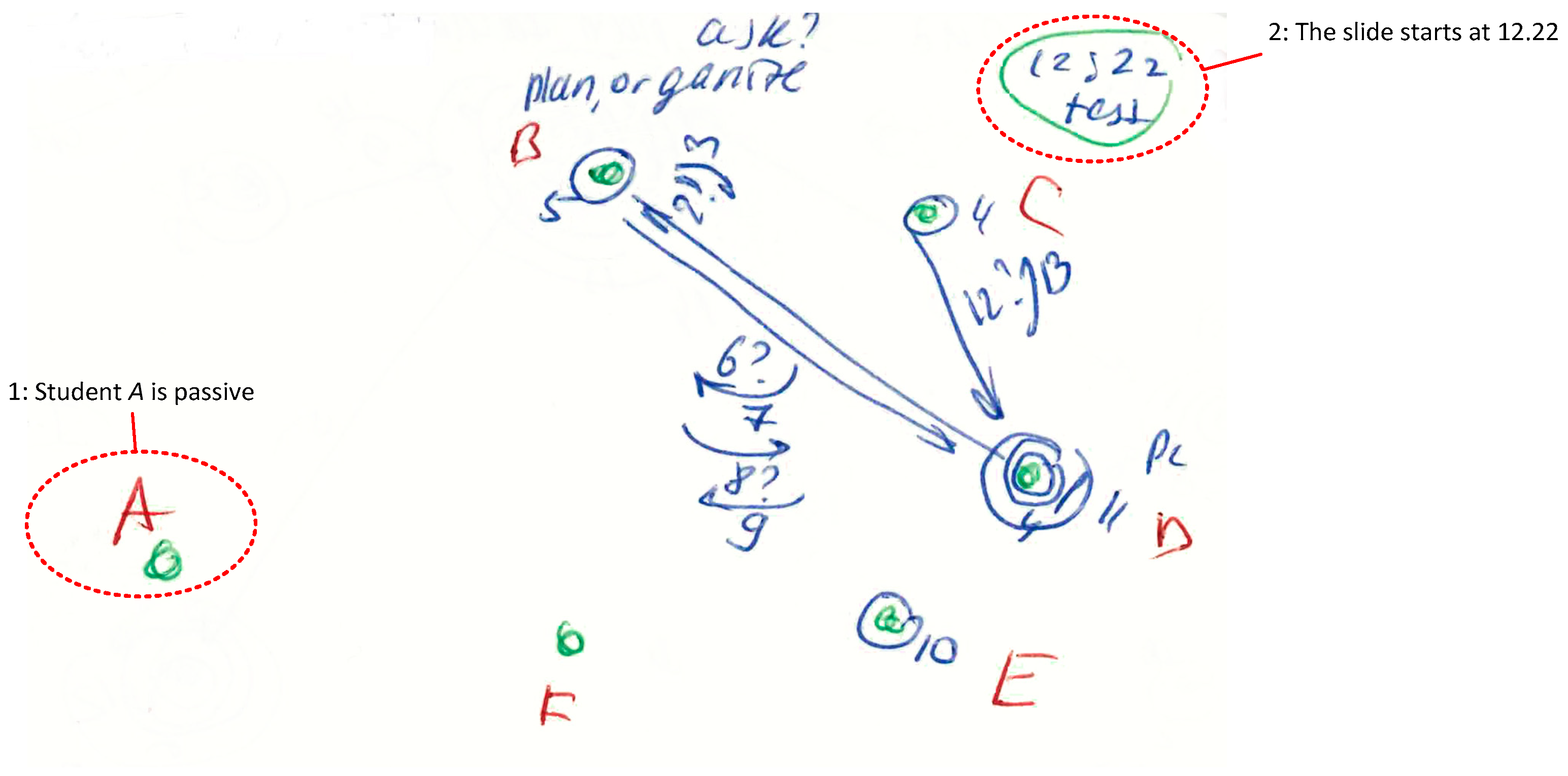

3.1. Basic Principles of the Interaction Diagram

Legend

- In the right corner, the researcher indicates the starting time for every slide and the current topic of discussion

- Numbers represent the sequence of communication interactions (every interaction starts with turn-taking)

- Letters represent the participants of the meeting

- A circle represents a broadcast speech that refers to everybody

- Arrows show the direction of communication

- A question sign represents a question asked by a particular person

- Small arrows near the question mark represent answers and repeating questions (see Figure 1)

- Notes may be written near participant’s letter, about his/her communication style or role

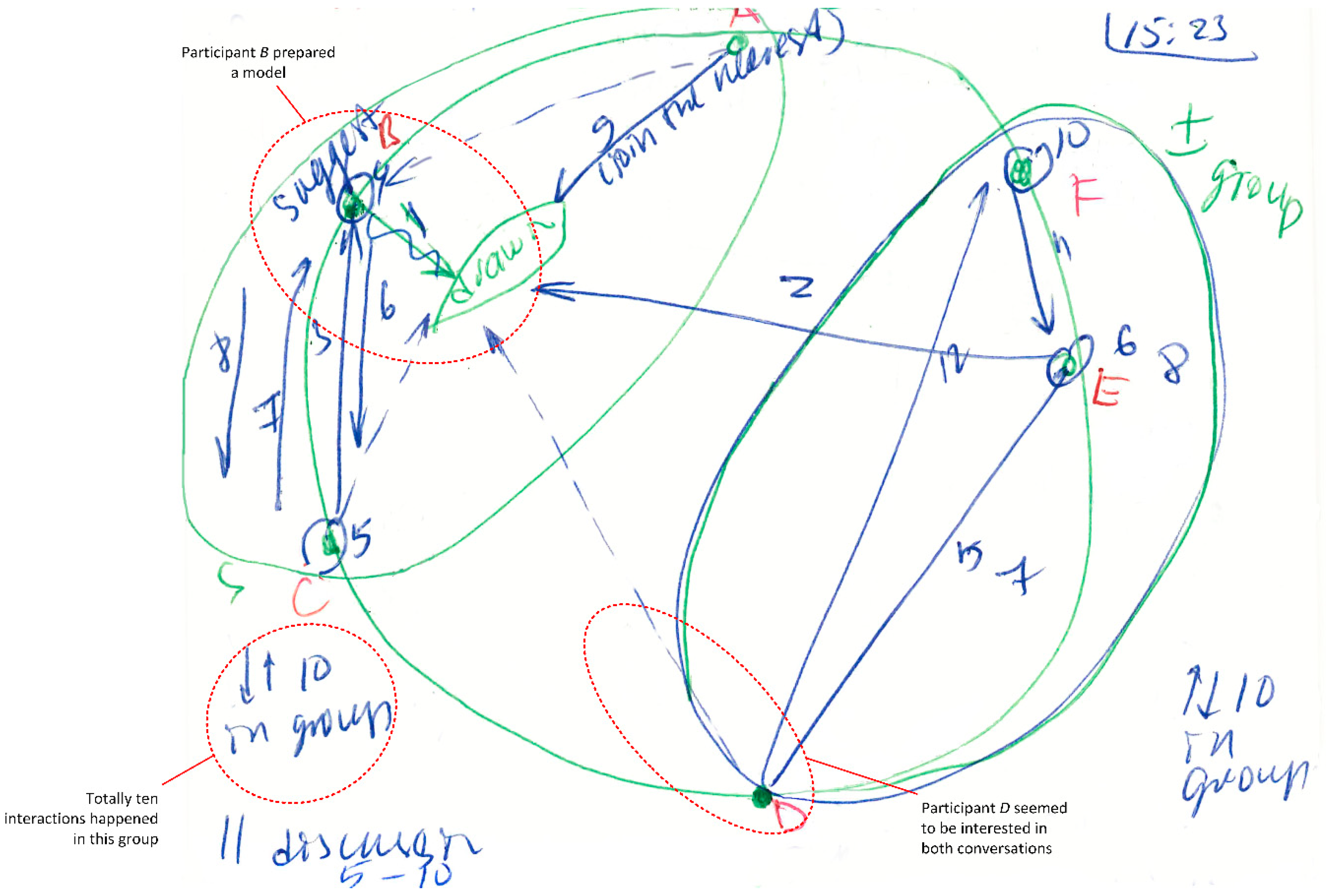

- Parallel discussions are shown as big circles around a particular group of participants (see Figure 3)

- Green colour shows participants, starting time and special marks; blue colour shows communication processes and notes about team roles; and red colour shows a name or abbreviations of participants

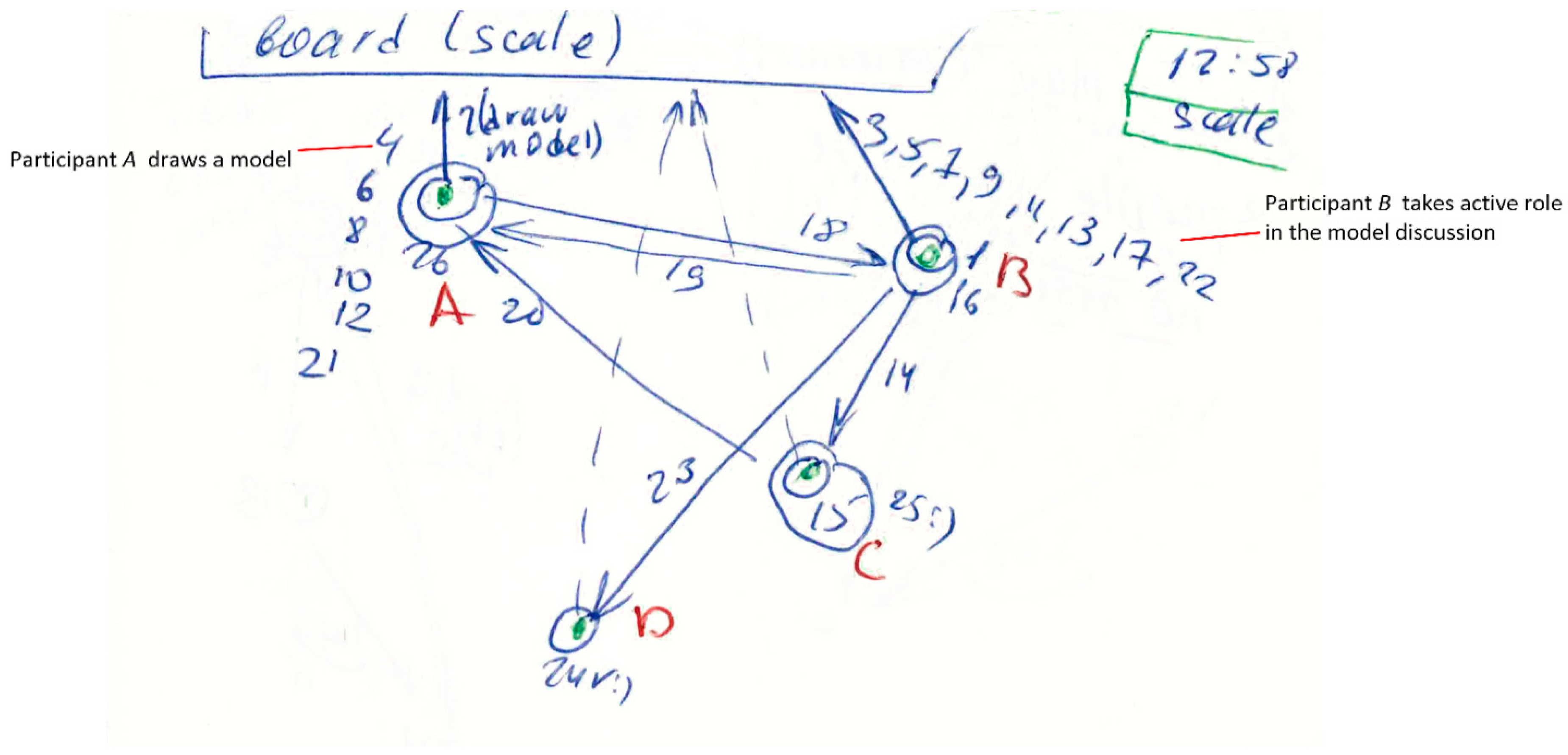

- Long monologue speech is shown as a thick line (arrow or circle)

- Repeating patterns are shown as small lines, as a separate group, with numbers of repeating interactions (see Figure 3)

- Solid line means verbal communication interaction, while dotted line is non-verbal (Figure 2)

3.2. Interaction Diagrams

3.2.1. Case 1: Simple Communication Situation

3.2.2. Case 2: Use of Artefacts

3.2.3. Case 3: Parallel Discussions

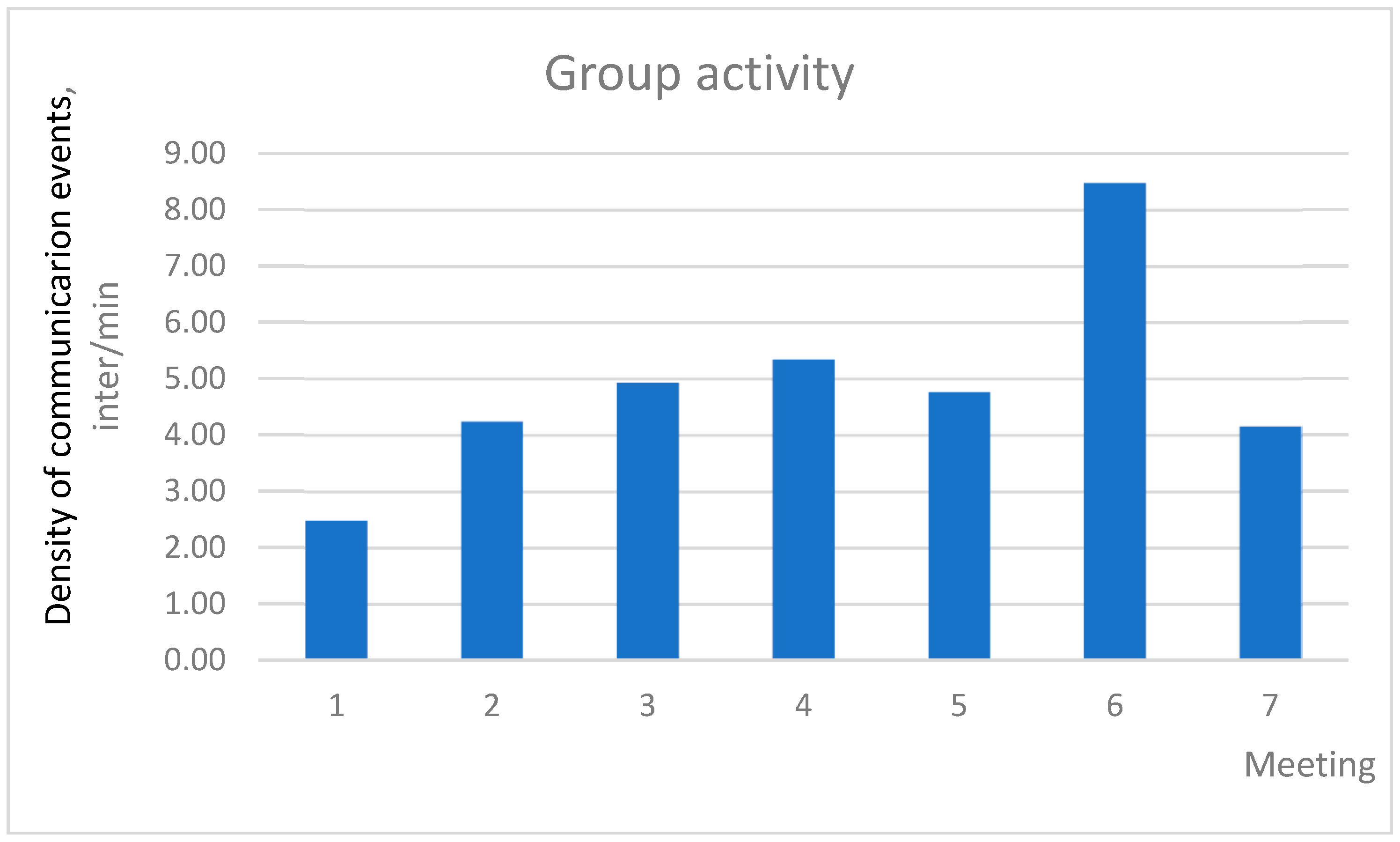

3.3. Quantitative Data Processing

- Total meeting time and time spent on every slide (observed communication part).

- Distribution of the main team roles among participants

- Addresser: initiates two or more interpersonal interactions, excluding artefacts

- Transmitter: comments three or more times (circle interactions on diagram)

- Information Provider: provides two or more answers

- Artefact Provider: shows any new artefact (e.g., models on paper, electronic models, physical objects, and presentations)

- ✓

- SENDER: This is the sum of the points for outcoming information (addresser, transmitter and provider roles)

- ✓

- RECEIVER: Receives two or more addressing interactions including answers

- ✓

- OUTSIDER: Has fewer than two interactions (any)

3.4. Qualitative Analysis

3.4.1. Analysis of Repeating Patterns of Communication Behaviour

3.4.2. Example of Data Extraction and Written Notes

3.4.3. Identification of Roles

- Participant A—Information provider (providing detailed and excessive information) and Representative (verbalising group’s feelings, providing an answer to the question that referred to all group)

- Participant B—Outsider (passive communication behaviour, almost did not participate in project discussion)

- Participant C—Information provider (providing detailed and excessive information), and Explorer (asking many questions)

- Participant D—Passive collector (non-verbal signs of agreement or just short yes/no answer, low verbal participation in team discussion, attentive listening)

- Participants E—Information provider (providing detailed and excessive information)

- Participant F—Facilitator (defining the task or group problem)

3.5. Combination of Observational Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Practicality of Observation and Preparation

4.2. Advantages of the Method

4.3. Point of Difference

- Allows recording time sequence

- Shows direction of member-to-member interactions

- Allows recording specific situational behaviour of different team members

- Records use of artefacts by participants

- Allows recording non-verbal behaviour, but only for a limited period of time

- Shows long monologue interaction

- Shows repeating patterns of the interactions between same group members

- Several interactions, e.g., non-verbal agreements, nodding or gestures would not have been detected with audio, but were captured with the ID method. With audio recording, there can also be identification problems with multiple people speaking at once, which is less of an issue with the ID method.

- Video could pick up all these and has the additional advantage of being able to be re-played. However, video recording changes the behaviour of participants, and requires more stringent ethics approvals.

4.4. Domain Specific and Generic Elements

4.5. Limitations of the Interaction Diagram Method

4.6. Application

4.7. Implications for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bailey, J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: Transcribing. Fam. Pract. 2008, 25, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, T.; Fisher, J.A. Benefits of ‘observer effects’: Lessons from the field. Qual. Res. 2010, 10, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, R.; Rui, Y.; Gupta, A.; Cadiz, J.J.; Tashev, I.; He, L.-W.; Colburn, A.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Silverberg, S. Distributed meetings: A meeting capture and broadcasting system. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Juan-les-Pins, France, 1–6 December 2002; pp. 503–512. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimes, A.; Omura, K.; Nagamine, T.; Hirata, K. Memory cues for meeting video retrieval. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Continuous Archival and Retrieval of Personal Experiences, New York, NY, USA, 15 October 2004; pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, L.; Haythorn, W.; Meirowitz, B.; Lanzetta, J. A note on a new technique of interaction recording. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1951, 46, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, P. Doing Conversation Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saindon, R.J.; Brand, S. Systems and Methods for Automated Audio Transcription, Translation, and Transfer. U.S. Patent No. US6820055B2, 25 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner, L.R.; Juang, B.-H. Fundamentals of Speech Recognition; PTR Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1993; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Signer, B. Fundamental Concepts for Interactive Paper and Cross-Media Information Spaces, 2nd ed.; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, S.; Hyland, P.; Wiley, M. Filochat: Handwritten notes provide access to recorded conversations. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 April 1994; pp. 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Stifelman, L.J. Augmenting real-world objects: A paper-based audio notebook. In Proceedings of the Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–18 April 1996; pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.K.B.; Wheaton, C.; Harden, D.K.; Buzzard, K.A. Smart Pen. U.S. Patent Application No. 29/483,634, 15 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Edgecomb, T.L.; Van Schaack, A.J. Content Selection in a Pen-Based Computing System. U.S. Patent No. CN104040469A, 23 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R.J. Technological Advances in the Analysis of Work in Dangerous Environments: Tree Felling and Rural Fire Fighting. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Chiang, A.-T.; Ning, X. Automatic Video Annotation System for Archival Sports Video. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Winter Applications of Computer Vision Workshops (WACVW), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 24–31 March 2017; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, P.J.; Hannafin, M. Video annotation tools: Technologies to scaffold, structure, and transform teacher reflection. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanos, S.; Akther, S.F.; Abdul-Basit, M.; McCabe, R.; Priebe, S. Using video-annotation software to identify interactions in group therapies for schizophrenia: Assessing reliability and associations with outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arawjo, I.; Yoon, D.; Guimbretière, F. TypeTalker: A Speech Synthesis-Based Multi-Modal Commenting System. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Portland, OR, USA, 25 February–1 March 2017; pp. 1970–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, S.; Berthouzoz, F.; Mysore, G.J.; Li, W.; Agrawala, M. Content-based tools for editing audio stories. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, St. Andrews, UK, 8–11 October 2013; pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman, V.; Yoon, D.; Mitros, P. Simplified Audio Production in Asynchronous Voice-Based Discussions. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 1045–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, B.; Carrasco, J.A.; Wellman, B. Visualizing personal networks: Working with participant-aided sociograms. Field Methods 2007, 19, 116–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaro, P.; Ryan, L.; D’Angelo, A. The visual sociogram in qualitative and mixed-methods research. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.L. Who Shall Survive? Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company: Washington, DC, USA, 1934; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt, H.J. Some effects of certain communication patterns on group performance. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1951, 46, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.E. Communication networks. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1964, 1, 111–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbie, F.; Reith, G.; McConville, S. Utilising social network research in the qualitative exploration of gamblers’ social relationships. Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, H.H. Sociometry in Group Relations: A Work Guide for Teachers; American Council on Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1948; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, F. Sociometry in physical education. J. Am. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1953, 24, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaro, P.; Casilli, A.A.; Mounier, L. Eliciting personal network data in web surveys through participant-generated sociograms. Field Methods 2014, 26, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T.W. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.L.; Lee, Y.S.; An, J.-Y. Application of social network analysis to health care sectors. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2012, 18, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, D.J. A social network perspective on industrial/organizational psychology. Handb. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 1, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tamassia, R. Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, L. Trending: The promises and the challenges of big social data. Debates Digit. Humanit. 2011, 2, 460–475. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann-Willenbrock, N.; Beck, S.J.; Kauffeld, S. Emergent team roles in organizational meetings: Identifying communication patterns via cluster analysis. Commun. Stud. 2016, 67, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benne, K.D.; Sheats, P. Functional roles of group members. J. Soc. Issues 1948, 4, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Tannenbaum, S.I.; Kukenberger, M.R.; Donsbach, J.S.; Alliger, G.M. Team Role Experience and Orientation A Measure and Tests of Construct Validity. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 6–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Addresser | Transmitter | Information Provider | Artefact Provider | Sender (sum) | Receiver | Outsider |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4A | 2A | - | 7A | 2A | - |

| - | 2B | - | - | 2B | - | 3B |

| 3C | 2C | - | - | 5C | C | 2C |

| - | 4D | - | - | 4D | - | - |

| - | 4E | - | - | 4E | 3E | 1E |

| 4F | 2F | F | F | 8F | - | 1F |

| Slide | Time, Min | Quantity of Interactions, Per Person | Density of Communication Events, Interactions Per Min | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | Total | A | B | C | D | E | F | ||

| 1 | 17 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 18 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 23 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.86 |

| 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 17 | 1.40 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.80 |

| 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 23 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 19 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.33 |

| Total | 46 | 27 | 9 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 114 | ||||||

| Density for every participant * (arithmetic mean) | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.61 | ||||||||

| Density for every participant * (average per meeting)—total quantity of interactions divided on total time | 0.59 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.48 | ||||||||

| Standard deviation between slides (for all group) | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.34 | ||||||||

| Standard deviation between participants (from arithmetic mean) | SD = 0.18 | |||||||||||||

| Standard deviation between participants (from average) | SD = 0.13 | |||||||||||||

| Coefficient of variation CV (slides) | 0.59 | 1.10 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.55 | ||||||||

| Coefficient of variation CV (participants) from the arithmetic mean | 0.37 | |||||||||||||

| Coefficient of variation CV (participants) from average | 0.31 | |||||||||||||

| Total group activity—2.48 inter/min | ||||||||||||||

| Meeting | Total Time, Min | Group Communication Activity, Interactions Per Minute [Mean] | Standard Deviation SD and Coefficient of Variation CV between Meetings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | 2.48 | |

| 2 | 55 | 4.24 | |

| 3 | 42 | 4.93 | SD = 1.82 |

| 4 | 50 | 5.34 | CV = 0.37 |

| 5 | 49 | 4.76 | |

| 6 | 58 | 8.48 | |

| 7 | 52 | 4.15 |

| N. | Team Roles | Typical Communication Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initiator (initiate process) | Active participation, propose new ideas and tasks, new directions of work. |

| 2 | Passive collector (collect information) | Passive data collecting, non-verbal signs of agreement or just short yes/no answer, low verbal participation in team discussion, attentive listening, and keeping ideas inside (non-vocalisation). |

| 3 | Explorer (ask questions) | High verbal participation, active data collecting: ask general questions, ask for different facts, ideas or opinions, and explore facts. Ask to clarify or specify ideas, define the term, and give an example. |

| 4 | Information provider (provide information) | Provide detailed and excessive information: take an active part in the conversation, but mostly talk rather than listen. |

| 5 | Facilitator (summarise, control discussion) | Define the task or group problem, suggest a method or process for accomplishing the task, provide a structure for the meeting, control the discussion processes. Bring together related ideas, restate suggestions after the group has discussed them, offer a decision or conclusion for the group to accept or reject. Get the group back to the track. |

| 6 | Arbitrator (solve disagreement) | Encourage the group to find agreement whenever miscommunication arises or group cannot come to a common position. |

| 7 | Representative (express, answer) | Verbalise group’s feelings, hidden problems, questions or ideas that others were afraid to express, provide an answer to questions that were referred to the whole group. |

| 8 | Gatekeeper (fill gaps, sensitive to others) | Help to keep communication channels open: fill gaps in conversation, ask a person for his/her opinion, be sensitive to the non-verbal signals indicating that people want to participate. |

| 9 | Connector (connect people) | Connect the team with people outside the group. |

| 10 | Outsider (stay outside) | Do not participate in project discussion. |

| Participant | Qualitative Team Role | Main Team Interactions (See Table 1) |

|---|---|---|

| A | Information provider | Sender |

| B | Outsider | Outsider/Transmitter |

| C | Information provider | Sender |

| D | Passive collector | Transmitter |

| E | Information provider | Not defined (equal distribution) |

| F | Facilitator | Sender (very active) |

| Meeting No. | Qualitative Analysis of the Total Group Activity (Notes from Observation) | Quantitative Analysis of the Total Group Activity, (Interactions per Minute) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The team members defined their tasked and goals. The middle communication activity | 2.48 (middle) |

| 2 | The dynamics of communication was at the low level initially and then increased towards the end of the meeting. | 4.24 (high) |

| 3 | The communication activity was rather high. There were nine people in the room. They all talk at the same time, and there were many discussions happened in parallel. | 4.93 (high) |

| 4 | The communication activity was very high. There were nine members of the team again. However, discussions in parallel were not observed. The appearance of boundary objects (computer model) intensified the communication strongly in the middle of the meeting. | 5.34 (above high) |

| 5 | The communication activity was high even if there were only four participants at the meeting. First, one of the students prepared the physical model, which was very intensively discussed. Then, another student explained his ideas on paper charts. Later, the third student showed video-presentation. That attracted big attention and caused an intensive wave of discussion again. | 4.76 (high) |

| 6 | The communication activity was extremely high. Discussion started intensively from the very beginning and continues until the end of the meeting. Participants talked at the same time, and there were many discussions happened simultaneously. The students and supervisors discussed the submission of the project proposal during the next week. Team members also used artefacts for explanations. In general, it was hard to record the communication in the team because of the high speed of turn-taking, and many discussions happened in parallel. | 8.48 (very high) |

| 7 | The discussion was not very intensive at the beginning and the end but revived in the middle when the supervisor came into the room. There were some parallel discussions only over the last 5 min of the meeting. The project proposal had already been submitted. | 4.15 (high) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nestsiarovich, K.; Pons, D. Interaction Diagrams: Development of a Method for Observing Group Interactions. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9010005

Nestsiarovich K, Pons D. Interaction Diagrams: Development of a Method for Observing Group Interactions. Behavioral Sciences. 2019; 9(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleNestsiarovich, Kristina, and Dirk Pons. 2019. "Interaction Diagrams: Development of a Method for Observing Group Interactions" Behavioral Sciences 9, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9010005

APA StyleNestsiarovich, K., & Pons, D. (2019). Interaction Diagrams: Development of a Method for Observing Group Interactions. Behavioral Sciences, 9(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9010005