‘Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality’ and Employee Innovative Behavior: Do Psychological Empowerment and ‘Perceptions of HRM System Strength’ Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality and Innovative Behavior

2.2. Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment

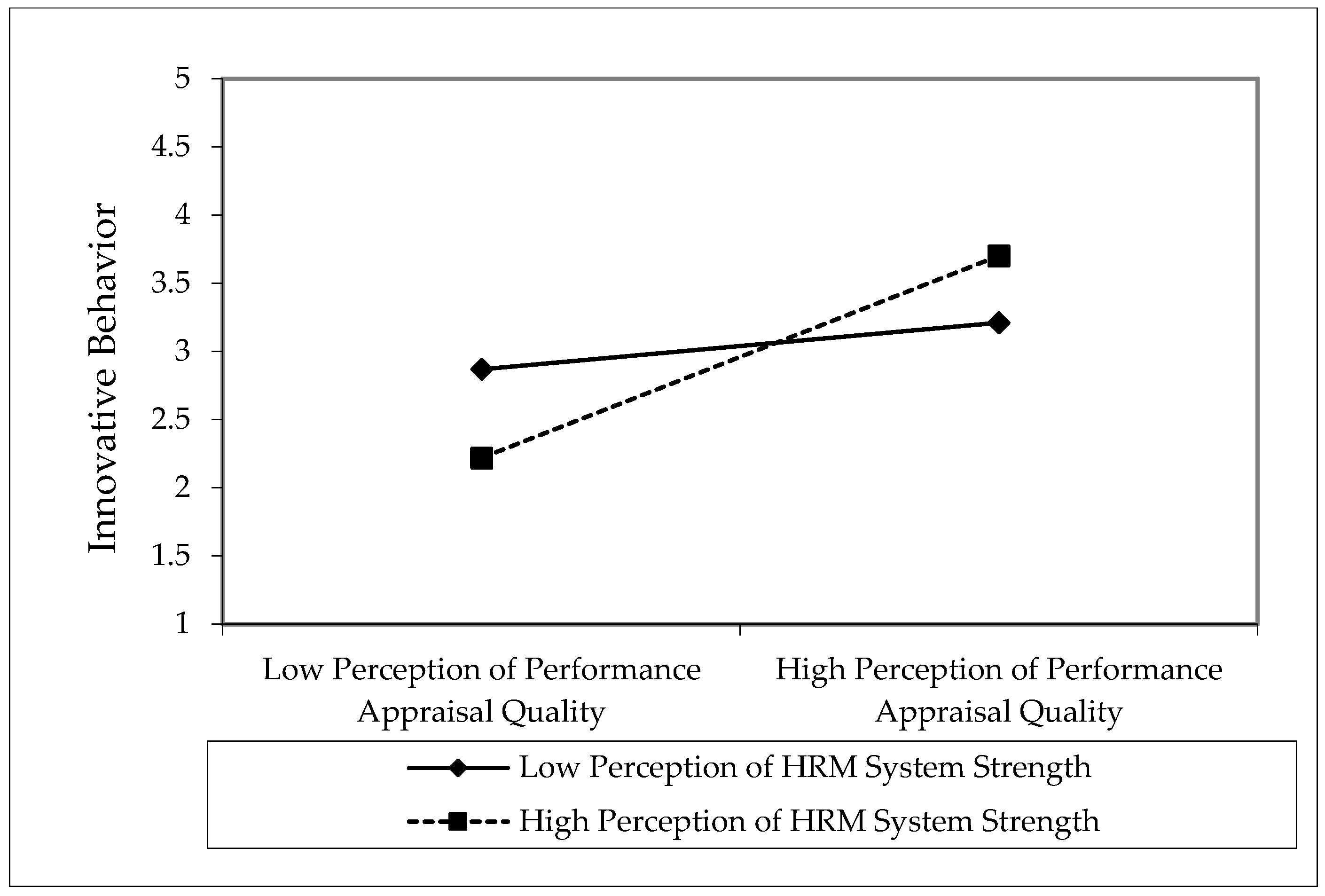

2.3. Moderating role of Perceptions of HRM System Strength

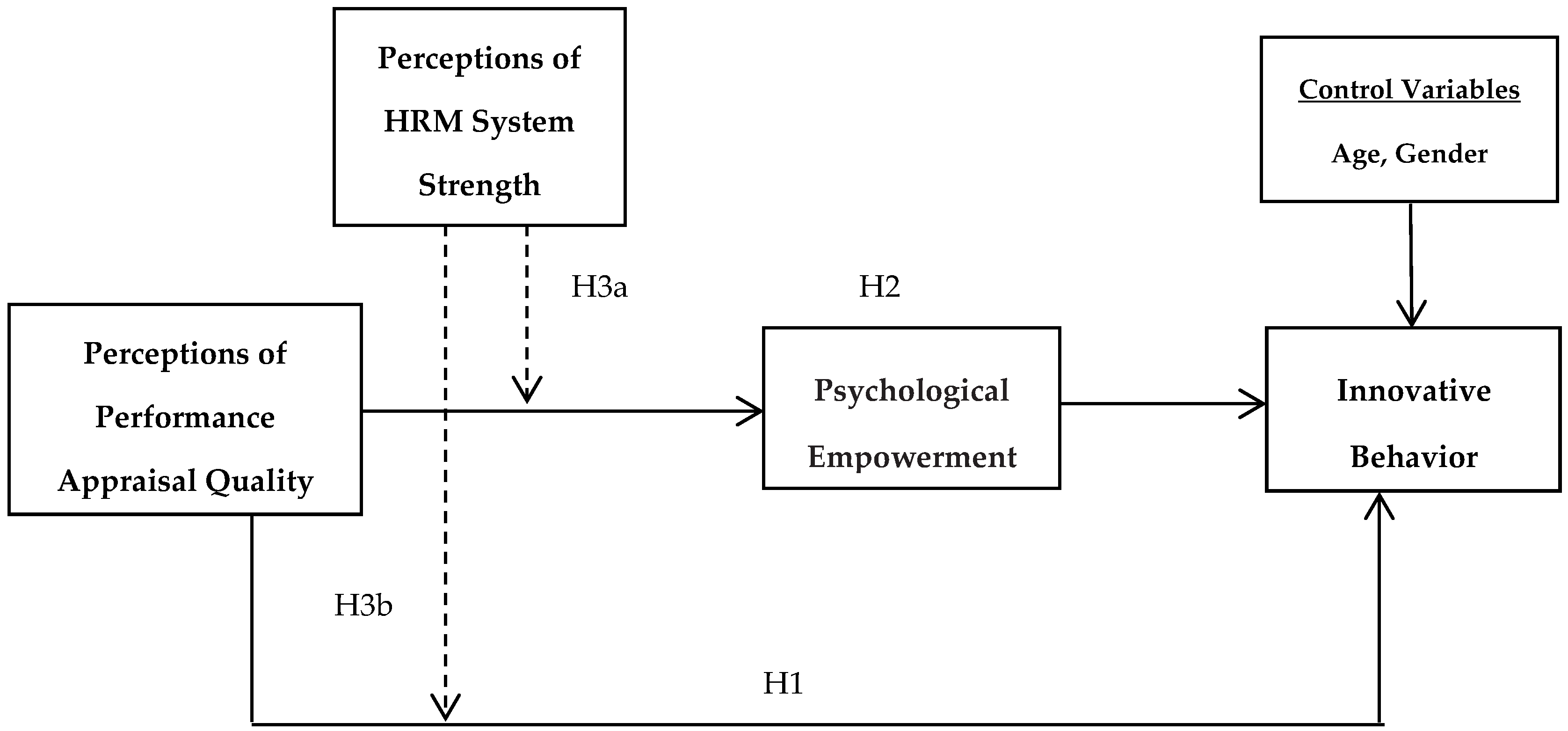

2.4. The Present Study

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Measures

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Results

4.1.1. Common Method Variance

4.1.2. Measurement Model

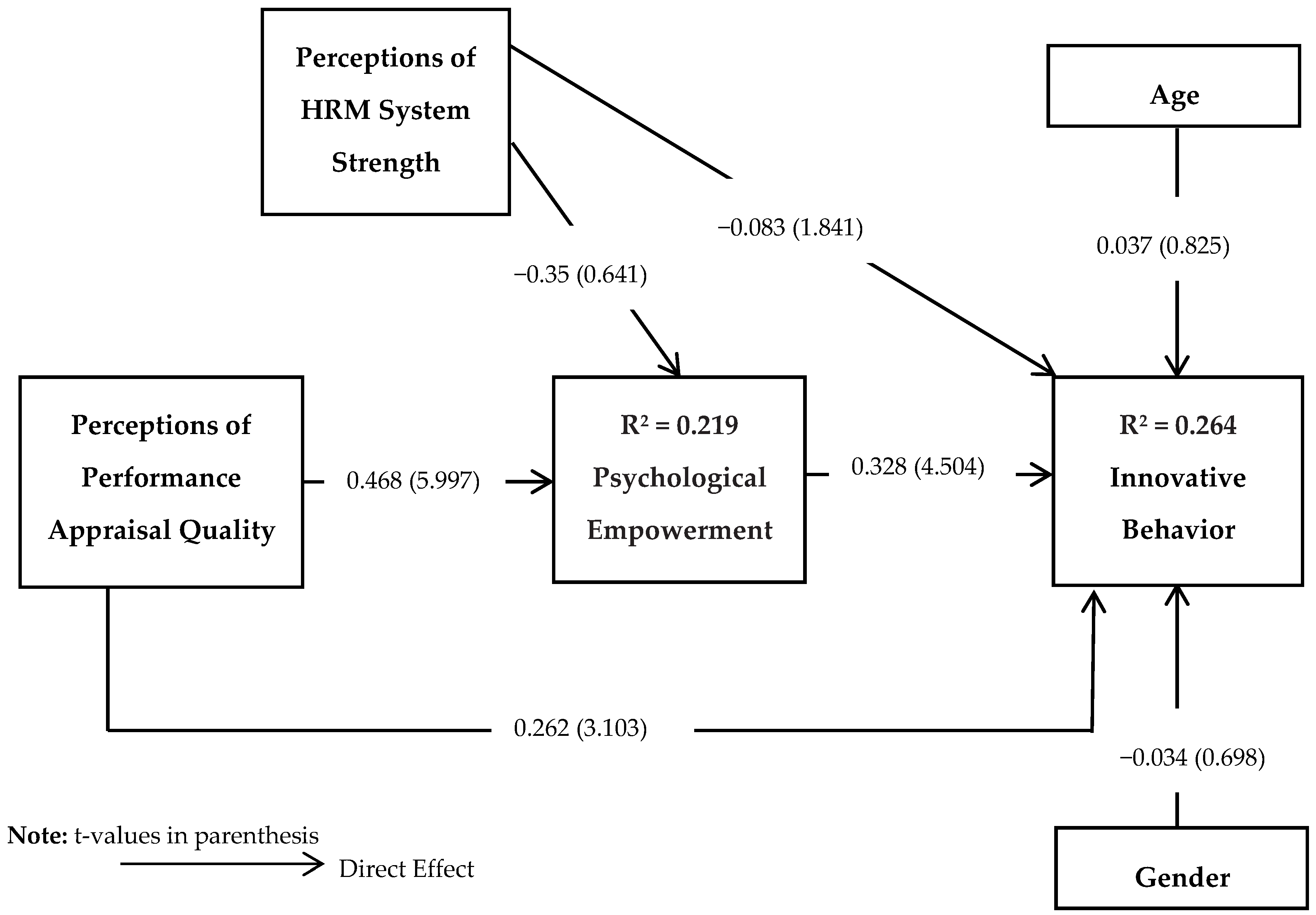

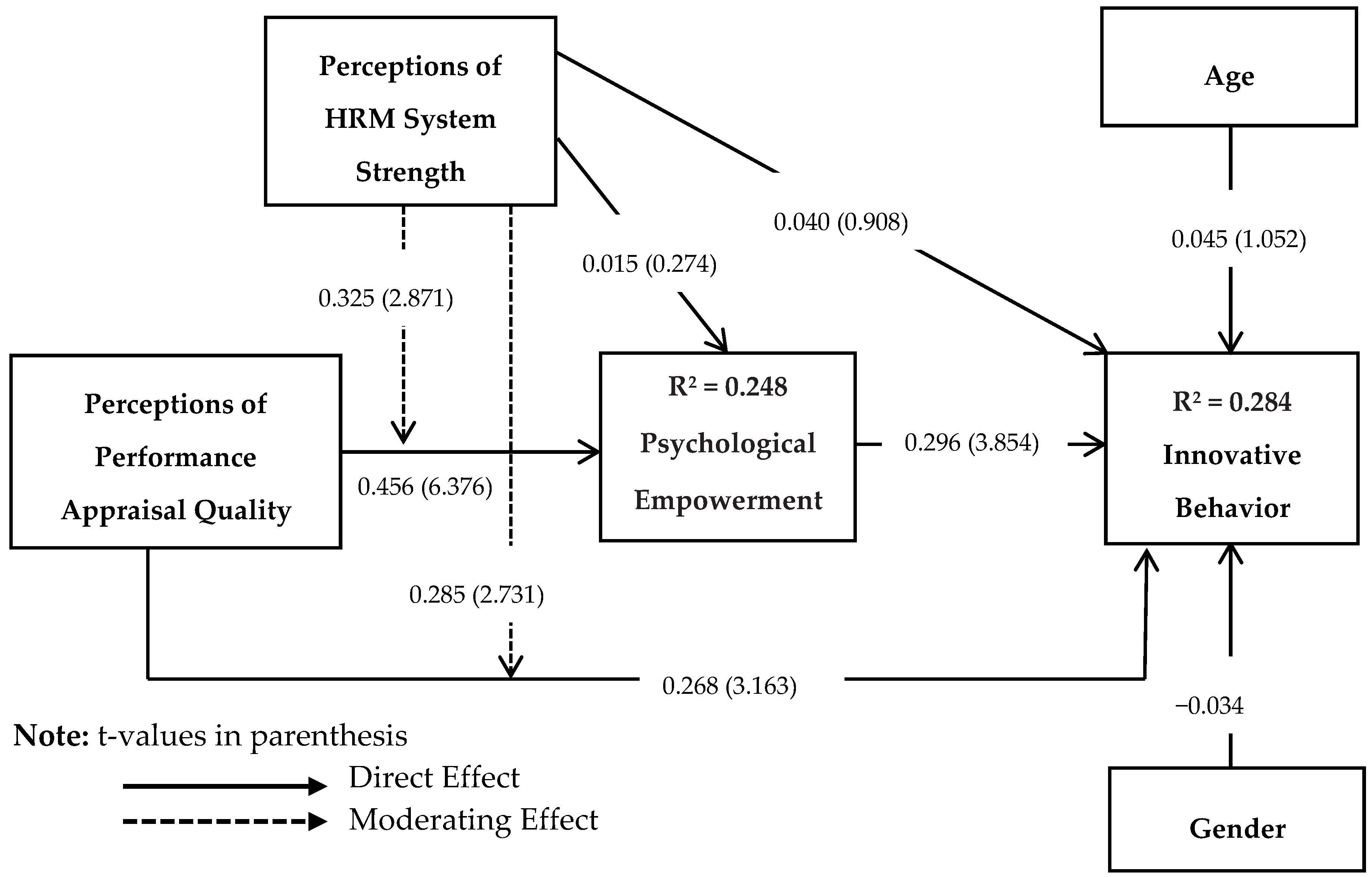

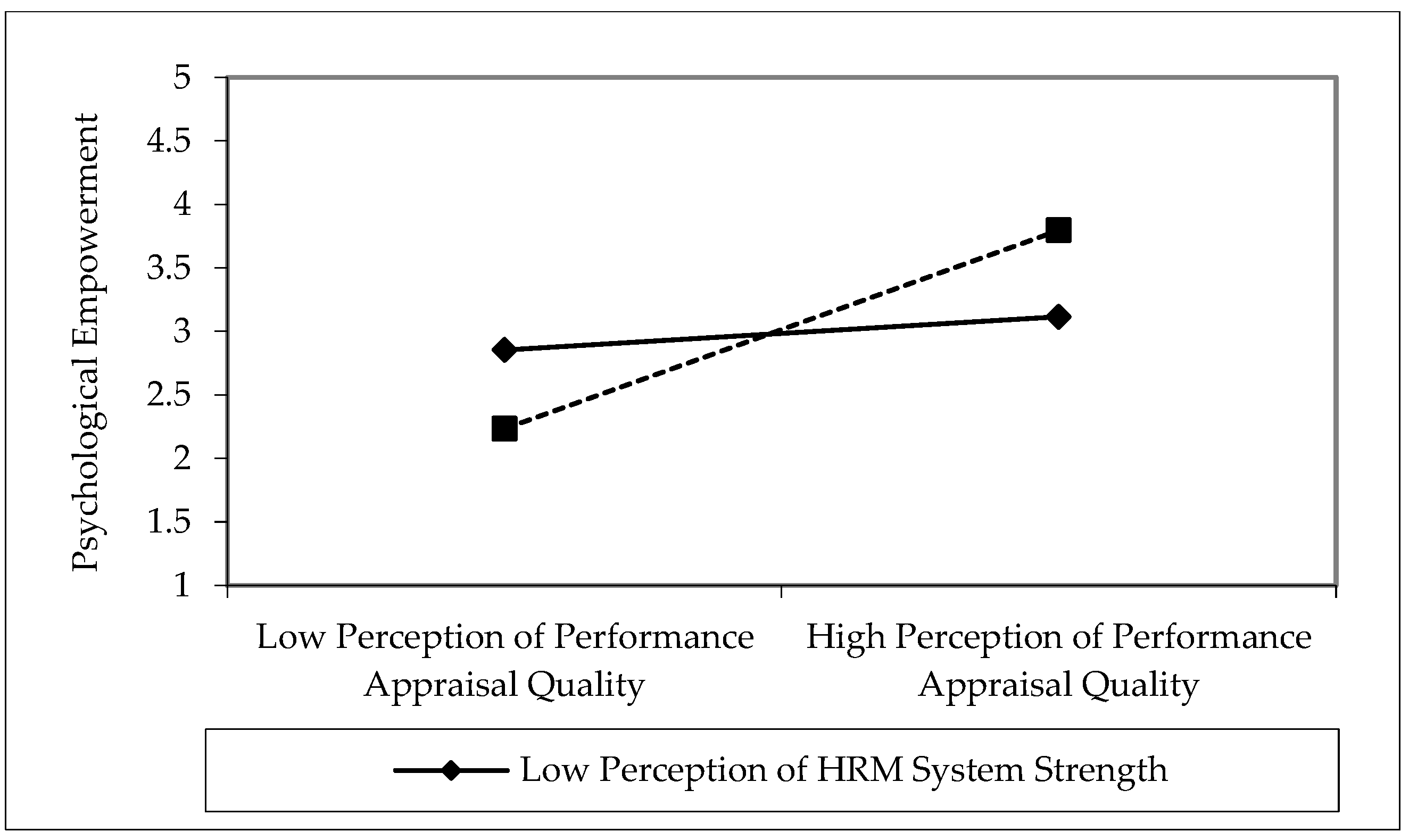

4.1.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

5.4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Omri, W. Innovative behavior and venture performance of SMEs: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 18, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, C.M.; Holman, D.J.; Unsworth, K.L.; Wall, T.D.; Waterson, P.E. Shopfloor innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological Factors Linking Perceived CSR to OCB: The Role of Organizational Pride, Collectivism, and Person–Organization Fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.A.u.; Usman, M.; Hussain, J. Enhancing Employee Innovative Behavior: The Moderating Effects of Organizational Tenure. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11. Available online: http://www.jespk.net/publications/396.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Janssen, O.; Vliert, E.v.d.; West, M. The Bright and Dark Sides of Individual and Group Innovation: A Special Issue Introduction. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Yuan, F.; Zhou, J. When perceived innovation job requirement increases employee innovative behavior: A sensemaking perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.F.; Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I. Understanding employee innovative behavior: Integrating the social network and leader–member exchange perspectives. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badirb, Y.; Khan, M.M. Person–job fit, person–organization fit and innovative work behavior: The mediating role of innovation trust. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2015, 26, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlings, M.; Evers, A.T.; Vermeulen, M. Toward a Model of Explaining Teachers’ Innovative Behavior: A Literature Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 20, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Following the Leader in R&D: The Joint Effect of Subordinate Problem-Solving Style and Leader-Member Relations on Innovative Behavior. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1998, 45, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: It’s Construct Clean-Up Time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.E. Employee Performance Appraisal System Participation: A Technique that Works. Public Pers. Manag. 2003, 32, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenbosch, L.; Engen, M.L.V.; Verhagen, M. On-the-job Innovation: The Impact of Job Design and Human Resource Management through Production Ownership. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2005, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of eVort–reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Behav. Sc. 1964, 9, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Social Psychology of Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1966; ISBN 10 0471023558. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative Behavior in the Workplace: The Role of Performance and Image Outcome Expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Naqvi, S.M.M.R.; Khan, A.K.; Arjoon, S.; Tayyeb, H.H. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. When a Thousand Flowers Bloom: Structural, Collective, and Social Conditions for Innovation in Organizations; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vegt, G.S.V.D.; Janssen, O. Joint Impact of Interdependence and Group Diversity on Innovation. J. Manag. Organ. 2003, 29, 729–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.P.J.D.; Hartog, D.N.D. How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2007, 10, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.F.; Cabrera, A. Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 16, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hsu, C.H.C. A review of employee innovative behavior in services. Int. J. Contem. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2820–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Darko, A. How Does Transformational Leadership Promote Innovation in Construction? The Mediating Role of Innovation Climate and the Multilevel Moderation Role of Project Requirements. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Iqbal, J.; Waheed, A.; Riaz, M.N. Relationship between Transformational Leadership Style and Innovative Work Behavior in Educational Institutions. J. Behav. Sci. 2012, 22, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Rhee, C.; Yoon, J. Organizational structure and innovation performance: Is employee innovative behavior a missing link? Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmann, G.; Mulder, R.H. Reflection as a facilitator of teachers’ innovative work behaviour. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M.J.; Brunetto, Y. Fostering innovative behaviour: The importance of employee commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3163–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining Structural Relationships between Work Engagement, Organizational Procedural Justice, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovative Work Behavior for Sustainable Organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S. Does HRM facilitate employee creativity and organizational innovation? A study of Chinese firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4025–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Seidu, E.Y.M.; Otaye, L.E. Impact of High-Performance Work Systems on Individual- and Branch-Level Performance: Test of a Multilevel Model of Intermediate Linkages. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, K.; Moorkamp, M.; Torka, N.; Groeneveld, S.; Groeneveld, C. How to Support Innovative Behaviour? The Role of LMX and Satisfaction with HR Practices. Technol. Invest. 2010, 1, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bysted, R.; Jespersen, K.R. Exploring Managerial Mechanisms that Influence Innovative Work Behaviour: Comparing private and public employees. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelaere, S.D.; Gyes, G.V.; Hootegem, G.V. Job Design and Innovative Work Behavior: One Size Does Not Fit All Types of Employees. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2012, 8, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bysted, R.; Hansen, J.R. Comparing Public and Private Sector Employees’ Innovative Behaviour: Understanding the role of job and organizational characteristics, job types, and subsectors. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Parker, S.K.; Jong, J.P.J.D. Need for Cognition as an Antecedent of Individual Innovation Behavior. J. Manag. Organ. 2014, 40, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knol, J.; Linge, R.V. Innovative behaviour: The effect of structural and psychological empowerment on nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, D.K.; Guthrie, J.P.; Wright, P.M. Human Resource Management and Labor Productivity: Does Industry Matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednall, T.C.; Sanders, K.; Runhaar, P. Stimulating Informal Learning Activities Through Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality and Human Resource Management System Strength: A Two-Wave Study. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2014, 13, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Ostroff, C. Understanding HRM–Firm Performance Linkages: The Role of the “Strength” of the HRM System. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Mawritz, M.B. Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and the moderating role of mechanistic–organic contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 35, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNisi, A.S.; Pritchard, R.D. Performance Appraisal, Performance Management and Improving Individual Performance: A Motivational Framework. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Murphy, K.R.; Cleveland, J.N.; Beaudin, G.; Marchand, S. Impact of Rater Beliefs Regarding Performance Appraisal and Its Organizational Context on Appraisal Quality. J. Bus. Psychol. 1998, 12, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, R.C.; Kirk, D.J. Distributive and Procedural Justice as Antecedents of Job Dissatisfaction and Intent to Turnover. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Hyatt, D.; Benson, J. Consequences of the performance appraisal experience. Pers. Rev. 2010, 39, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, D.J.; Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. Higher Educ. Policy 2006, 31, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, A.Z.; Shigutu, A.D.; Tensay, A.T. The Effect of Employees’ Perception of Performance Appraisal on Their Work Outcomes. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2014, 2, 136–173. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, C.; Williams, R. Performance Management, Job Satisfaction -and Organizational Commitment. Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darehzereshki, M. Effects of Performance Appraisal Quality on Job Satisfaction in Multinational Companies in Malaysia. Int. J. Enterp. Comput. Bus. Syst. 2013, 2. Available online: http://www.ijecbs.com/January2013/5.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertnerc, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. Organ. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. Research and theory on high-performance work systems: Progressing the high involvement stream. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009, 19, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Tyler, T.R. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-306-42726-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, J.C.; Johnson, P.D.; Mathe, K.; Paul, J. Structural and psychological empowerment climates, performance, and the moderating role of shared felt accountability: A managerial perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. Taking Stock: A Review of More Than Twenty Years of Research on Empowerment at Work. In Handbook of Organizational Behavior; Barling, J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. The Empowerment Process: Integrating Theory and Practice. Acad. Manag. Feview 1988, 13, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive Elements of Empowerment: An “Interpretive” Model of Intrinsic Task Motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Sparrowe, R.T. An Examination of the Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment on the Relations Between the Job, Interpersonal Relationships, and Work Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 83, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Bowen, D.E. Moving HR to a higher level: HR practices and organizational effectiveness. In Multilevel theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations; Kozlowski, S.W.J., Klein, K.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 211–266. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and Consequences of Psychological and Team Empowerment in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Patel, P.C.; Lepak, D.P.; Gould-Williams, J.S. Unlocking the Black Box: Exploring the Link Between High-Performance Work Systems and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, S.; Moldogaziev, T. Using Employee Empowerment to Encourage Innovative Behavior in the Public Sector. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 23, 155–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chow, I.H.-S.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H. Mediating links between HRM bundle and individual innovative behavior. J. Manag. Organ. 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Bos-Nehles, A. HRM and performance: The role of effective implementation. In HRM and Performance: Achievements and Challenges, 1st ed.; Paauwe, J., Guest, D.E., Wright, P.M., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, Sussex, UK, 2012; pp. 79–96. ISBN 978-1405168335. [Google Scholar]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee Attributions of the “Why” of HR Practices: Their Effects on Employee Attitudes and Behaviors, and Customer Satisfaction. Person. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilji, S.E.; Wang, X. ‘Intended’ and ‘implemented’ HRM: The missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J.; Alfes, K. Attribution theories in Human Resource Management research: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 87–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, J.; Winne, S.D.; Sels, L. Toward an assessment of perceived HRM system strength: Scale development and validation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1481–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Bryson, A. Positive employee attitudes: How much human resource management do you need? Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, S.A.; Doh, J.P.; Tymon, W.G. The strength of HR practices in India and their effects on employee career success, performance, and potential. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2010, 49, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veld, M.; Paauwe, J.; Boselie, P. HRM and Strategic Climates in Hospitals: Does the Message Come Across at the Ward Level? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2010, 20, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The Processes of Causal Attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winne, S.D.; Delmotte, J.; Gilbert, C.; Sels, L. Comparing and explaining HR department effectiveness assessments: Evidence from line managers and trade union representatives. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1708–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, K.K. In the Eyes of the Beholder: An Attributional Approach to Ingratiation and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafferkey, K.; Heffernan, M.; Harney, B.; Dundon, T.; Townsend, K. Perceptions of HRM system strength and affective commitment: The role of human relations and internal process climate. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Dorenbosch, L.; Reuver, R.D. The impact of individual and shared employee perceptions of HRM on affective commitment: Considering climate strength. Person. Rev. 2008, 37, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; Winne, S.D.; Sels, L. Strong HRM processes and linemanagers’ effective HRM implementation: A balanced view. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2015, 25, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Conway, N. The impact of HR practices, HR effectiveness and a ‘strong HR system’ on organisational outcomes: A stakeholder perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 686–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.M.M.; Gomes, J.F.S. The strength of human resource practices and transformational leadership: Impact on organisational performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4301–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, Z. The effects of human resource attributions on employee outcomes during organizational change. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorde, K.V.D.; Beijer, S. The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2014, 25, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S.J.; Li, M.; Restubog, S.L.D. Management, Organizational Justice and Emotional Exhaustion among Chinese Migrant Workers: Evidence from two Manufacturing Firms. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 50, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Frenkel, S.J.; Sanders, K. Strategic HRM as process: How HR system and organizational climate strength influence Chinese employee attitudes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1825–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Bowen, D.E. Reflections on the 2014 Decade Award: Is There Strength in the Construct of HR System Strength? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Incorporation and institutionalization of SD into universities: Breaking through barriers to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynaghi, A.; Trencher, G.; Moztarzadeh, F.; Mozafari, M.; Maknoon, R.; Filho, W.L. Future sustainability scenarios for universities: Moving beyond the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3464–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Seatter, C.S. Teaching organisational change management for sustainability: Designing and delivering a course at the University of Leeds to better prepare future sustainability change agents. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.I.; Aslam, H.D.; Yousaf, S.; Noor, A. A critical analysis of performance appraisal system for teachers in public sector universities of Pakistan: A case study of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur (IUB). Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K. Overall Assessment of the Higher Education Sector; Higher Education Commission (HEC): H-9, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2016; pp. 1–80. Available online: http://hec.gov.pk/english/universities/projects/TESP/Documents/FR-Assessment%20HE%20Sector.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing (Advances in International Marketing); Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Krey, N. Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and Recommendations. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 11, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First-Order Constructs | Second-Order Constructs | Indicator’s | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | Convergent Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality | PQ1 PQ2 PQ3 | 0.883 0.869 0.891 | 0.912 | 0.776 | Yes | |

| Meaning | ME1 ME2 ME3 | 0.940 0.937 0.938 | 0.957 | 0.880 | Yes | |

| Competence | CO1 CO2 CO3 | 0.927 0.929 0.937 | 0.951 | 0.867 | Yes | |

| Self-Determination | SD1 SD2 SD3 | 0.936 0.938 0.934 | 0.955 | 0.876 | Yes | |

| Impact | IM1 IM2 IM3 | 0.950 0.956 0.948 | 0.855 | 0.664 | Yes | |

| Psychological Empowerment | Meaning Competence Self-Determination Impact | 0.894 0.898 0.881 0.877 | 0.937 | 0.788 | Yes | |

| Distinctiveness | DI1 DI2 DI3 DI4 DI5 DI6 | 0.853 0.845 0.841 0.880 0.823 0.852 | 0.939 | 0.721 | Yes | |

| Consistency | CT1 CT2 CT3 CT4 CT5 CT6 | 0.840 0.872 0.907 0.914 0.815 0.836 | 0.947 | 0.748 | Yes | |

| Consensus | CS1 CS2 CS3 CS4 | 0.922 0.921 0.922 0.920 | 0.957 | 0.848 | Yes | |

| Perceptions of HRM system strength | Distinctiveness Consistency Consensus | 0.915 0.916 0.908 | 0.938 | 0.834 | Yes | |

| Innovative Behavior | IB1 IB2 IB3 IB4 IB5 | 0.838 0.856 0.889 0.822 0.805 | 0.924 | 0.710 | Yes | |

| Constructs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality | 4.100 | 0.646 | 0.881 | ||||||||

| 2. Meaning a | 4.108 | 0.799 | 0.433 | 0.938 | |||||||

| 3. Competence a | 4.092 | 0.780 | 0.424 | 0.788 | 0.931 | ||||||

| 4. Self-Determination a | 4.025 | 0.821 | 0.376 | 0.695 | 0.717 | 0.936 | |||||

| 5. Impact a | 3.989 | 0.928 | 0.398 | 0.690 | 0.686 | 0.720 | 0.951 | ||||

| 6. Distinctiveness b | 4.373 | 0.596 | 0.065 | 0.047 | 0.010 | 0.036 | −0.066 | 0.849 | |||

| 7. Consistency b | 4.182 | 0.639 | 0.023 | 0.002 | −0.032 | 0.009 | −0.099 | 0.731 | 0.865 | ||

| 8. Consensus b | 4.263 | 0.672 | 0.044 | 0.026 | −0.027 | 0.001 | −0.062 | 0.767 | 0.758 | 0.921 | |

| 9. Innovative Behavior | 4.386 | 0.587 | 0.399 | 0.414 | 0.395 | 0.396 | 0.451 | −0.083 | −0.057 | −0.051 | 0.843 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waheed, A.; Abbas, Q.; Malik, O.F. ‘Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality’ and Employee Innovative Behavior: Do Psychological Empowerment and ‘Perceptions of HRM System Strength’ Matter? Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8120114

Waheed A, Abbas Q, Malik OF. ‘Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality’ and Employee Innovative Behavior: Do Psychological Empowerment and ‘Perceptions of HRM System Strength’ Matter? Behavioral Sciences. 2018; 8(12):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8120114

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaheed, Aamer, Qaisar Abbas, and Omer Farooq Malik. 2018. "‘Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality’ and Employee Innovative Behavior: Do Psychological Empowerment and ‘Perceptions of HRM System Strength’ Matter?" Behavioral Sciences 8, no. 12: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8120114

APA StyleWaheed, A., Abbas, Q., & Malik, O. F. (2018). ‘Perceptions of Performance Appraisal Quality’ and Employee Innovative Behavior: Do Psychological Empowerment and ‘Perceptions of HRM System Strength’ Matter? Behavioral Sciences, 8(12), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8120114