Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Crismon, M.L.; Kashner, T.M.; Toprac, M.G.; Carmody, T.J.; Key, T.; Biggs, M.M.; Shores-Wilson, K.; Witte, B.; et al. Clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.; Pfennig, A.; Linden, M.; Smolka, M.N.; Neu, P.; Adli, M. Efficacy of an algorithm-guided treatment compared with treatment as usual: A randomized, controlled study of inpatients with depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Xiang, Y.T.; Xiao, L.; Hu, C.Q.; Chiu, H.F.; Ungvari, G.S.; Correll, C.U.; Lai, K.Y.; Feng, L.; Geng, Y.; et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: A randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.; McGlinchey, J.B. Why don’t psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 68, 1916–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, D.R.; Ogles, B.M. Why some clinicians use outcome measures and others do not. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2007, 34, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, P. Rating scales in depression: Limitations and pitfalls. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Kishimoto, T.; Kane, J.M. Randomized controlled trials in schizophrenia: Opportunities, limitations, and trial design alternatives. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, A.M. Symptom rating scales and outcome in schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, s7–s14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.M.; Greenberg, J.M.; IsHak, W.W. Incorporating multidimensional patient-reported outcomes of symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the Individual Burden of Illness Index for Depression to measure treatment impact and recovery in MDD. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, M.H.; Clary, C.; Fayyad, R.; Endicott, J. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Harnett-Sheehan, K.; Raj, B.A. The measurement of disability. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1996, 11 (Suppl. 3), 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.H.; Chou, L.S.; Chen, M.C.; Chen, C.C. The relationship between symptom relief and functional improvement during acute fluoxetine treatment for patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 182, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.B.; Cornell, J.; Villanueva, M.; Retzlaff, P.J. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised Edition; Guy, W., Ed.; NIMH Publication: Rockville, MD, USA, 1976; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg, A.A.; DeCecco, L.M. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: A focus on treatment-resistant depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62 (Suppl. 16), 5–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shear, M.K.; Vanderbilt, J.; Rucci, P.; Endicott, J.; Lydiard, B.; Otto, M.W.; Pollack, M.H.; Chandler, L.; Williams, J.; Ali, A.; et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depress. Anxiety 2001, 13, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.B.W.; Kobak, K.A. Development and Reliability of the SIGMA: A structured interview guide for the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanello, A.; Berthoud, L.; Ventura, J.; Merlo, M.C.G. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (version 4.0) factorial structure and its sensitivity in the treatment of outpatients with unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebowitz, M.R.; Gorman, J.M.; Fyer, A.J.; Campeas, R.; Levin, A.P.; Sandberg, D.; Hollander, E.; Papp, L.; Goetz, D. Pharmacotherapy of social phobia: An interim report of a placebo-controlled comparison of phenelzine and atenolol. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1988, 49, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearing, M.K.; Post, R.M.; Leverich, G.S.; Brandt, D.; Nolen, W. Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): The CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res. 1997, 73, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, J.M.; Kamath, S.A.; Ochoa, S.; Novick, D.; Rele, K.; Fargas, A.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Rele, R.; Orta, J.; Kharbeng, A.; et al. The Clinical Global Impression–Schizophrenia scale: A simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003, 107 (Suppl. 416), 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, E.; Robin, J.L. Multicentric double-blind study comparing efficacy and safety of minaprine and imipramine in dysthymic disorders. Neuropsychobiology 1995, 31, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targum, S.D.; Hassman, H.; Pinho, M.; Fava, M. Development of a clinical global impression scale for fatigue. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 46, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malow, B.A.; Connolly, H.V.; Weiss, S.K.; Halbower, A.; Goldman, S.; Hyman, S.L.; Katz, T.; Madduri, N.; Shui, A.; Macklin, E.; et al. The Pediatric Sleep Clinical Global Impressions Scale—A new Tool to measure pediatric insomnia in autism spectrum disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016, 37, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, K.; Frank, E.; Houck, P.R.; Reynolds, C.F. Treatment of complicated grief. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, M.K.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Simon, N.M.; Zisook, S.; Wang, Y.; Mauro, C.; Duan, N.; Lebowitz, B.; Skritskaya, N. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, A.H.; O’Connor, C.M.; Califf, R.M.; Swedberg, K.; Schwartz, P.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Krishnan, K.R.; van Zyl, L.T.; Swenson, J.R.; Finkel, M.S.; et al. Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHEART) Group. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, F.; Lohaus, A.; Gutzmann, H. Reliability and clinical concepts underlying global judgments in dementia: Implications for clinical research. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1992, 28, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weitkunat, R.; Letzel, H.; Kanowski, S.; Grobe-Einsler, R. Clinical and psychometric evaluation of the efficacy of nootropic drugs: Characteristics of several procedures. Zeitschrift für Gerontopsychologie und-Psychiatrie 1993, 6, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Beneke, M.; Rasmus, W. “Clinical Global Impressions” (ECDEU): Some Critical Comments. Pharmacopsychiatry 1992, 25, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, A.C.; Shear, M.K.; Klerman, G.L.; Portera, L.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Goldenberg, I.A. Comparison of symptom determinants of patient and clinician global ratings in patients with panic disorder and depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993, 13, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielmans, G.I.; McFall, J.P. A comparative meta-analysis of Clinical Global Impressions change in antidepressant trials. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaider, T.I.; Heimberg, R.G.; Fresco, D.M.; Schneier, F.R.; Liebowitz, M.R. Evaluation of the Clinical Global Impression Scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, K.; Pearlstein, T.; Asnis, G.M.; Baker, D.; Rothbaum, B.; Sikes, C.R.; Farfel, G.M. Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000, 283, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Gorman, J.M.; Shear, M.K.; Woods, S.W. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000, 283, 2529–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I.; McElroy, S.L.; Raymond, N.C.; Crow, S.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Carter, W.P.; Mitchell, J.E.; Strakowski, S.M.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Coleman, B.S.; et al. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: A multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 1756–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Targum, S.D.; Houser, C.; Northcutt, J.; Little, J.A.; Cutler, A.J.; Walling, D.P. A structured interview guide for global impressions: Increasing reliability and scoring accuracy for CNS trials. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2013, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forkmann, T.; Scherer, A.; Boecker, M.; Pawelzik, M.; Jostes, R.; Gauggel, S. The clinical global impression scale and the influence of patient or staff perspective on outcome. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leucht, S.; Engel, R.R. The relative sensitivity of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in antipsychotic drug trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, K.J.; Rush, A.J.; Arbuckle, M.; Trivedi, M.H.; Pincus, H.A. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: A policy framework for implementation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortney, J.C.; Unützer, J.; Wrenn, G.; Pyne, J.M.; Smith, G.R.; Schoenbaum, M.; Harbin, H.T. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatry Serv. 2017, 68, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Toward Quality Measures for Population Health and the Leading Health Indicators; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Keyser, D.; Pincus, H.A. Challenges and opportunities in measuring the quality of mental health care. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-S.; Nkouibert Assam, P.; Gersing, K.R.; Chan, E.; Burchett, B.M.; Sim, K.; Feng, L.; Krishnan, K.R.; Rush, A.J. The Effectiveness of antidepressant monotherapy in a naturalistic outpatient setting. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012, 14, PCC.12m01364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Brodhead, A.E.; Kolts, R.L. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale, the Hamilton depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials: A replication analysis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 19, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Chouinard, G.; Cohn, C.K.; Cole, J.O.; Itil, T.M.; LaPieree, Y.D.; Masco, H.L.; Mendels, J. Antidepressant efficacy of sertraline: A double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1990, 51 (Suppl. B), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Targum, S.D.; Busner, J.; Young, A.H. Targeted scoring criteria reduce variance in global impressions. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 23, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busner, J.; Targum, S.D. The Clinical Global Impressions Scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007, 4, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

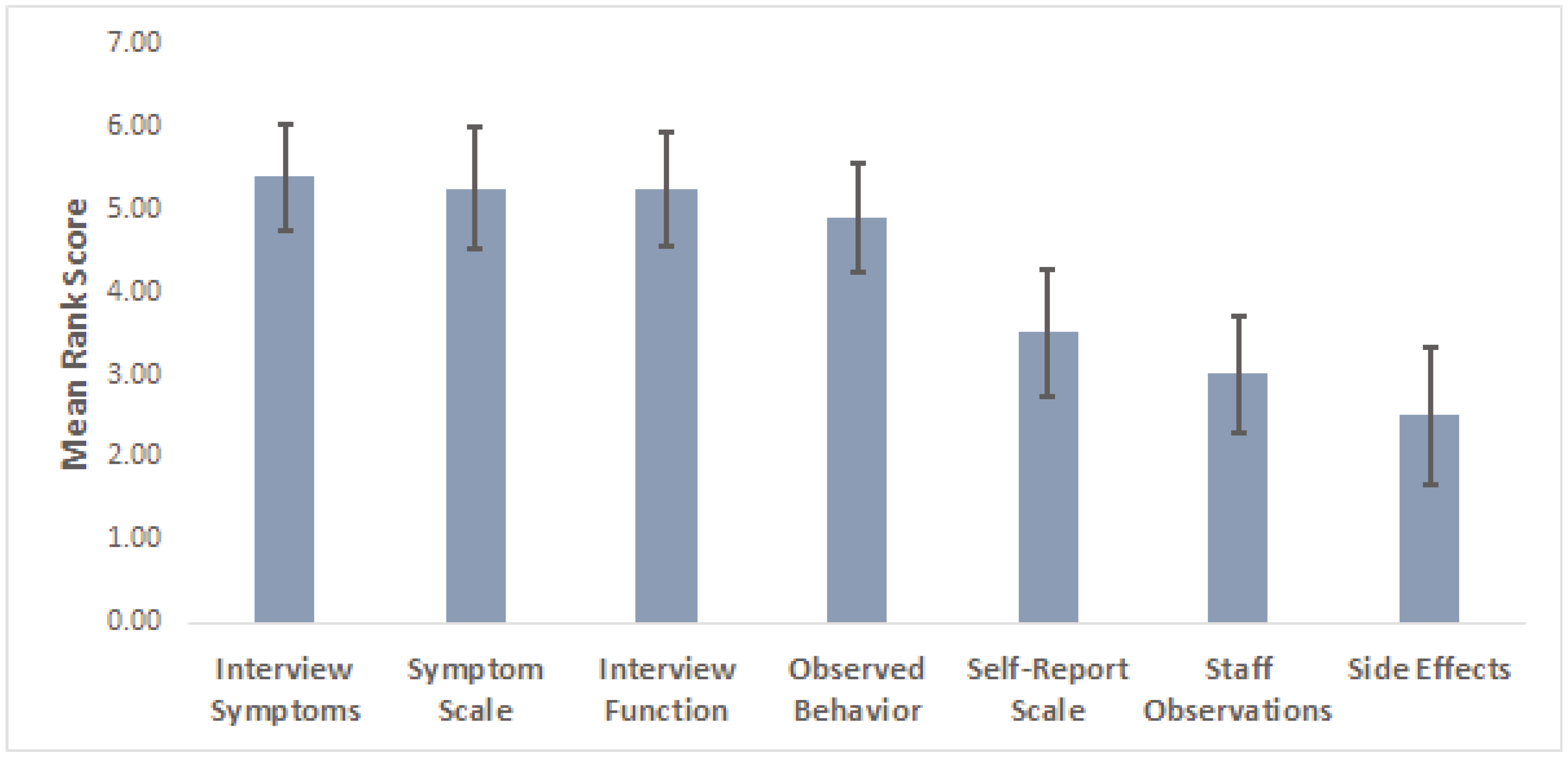

| Factor | Ranking (1–7) |

|---|---|

| Patient’s verbal report of symptom severity during interview | |

| Patient’s verbal report of their functional status | |

| Observable aspects of patient’s behavior | |

| Objective rating scale score (Hamilton, Montgomery-Asberg) | |

| Subjective rating scale scores (Beck, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology) | |

| Degree of side-effects experienced by patient | |

| Comments from study coordinator or other study staff regarding their observations of the patient | |

| Other (Please write in): |

| T-CGI-Severity | T-CGI-Improvement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity Rating | Severity Level Description | Improvement Rating | Improvement Level Description |

| 1. Normal | Symptoms are rarely present and occur only in contextually appropriate circumstances. The patient reports functioning at or very close to their full capacity. | 1. Very much improved | Both the patient and the clinician agree that he/she has improved greatly from baseline, both in terms of symptoms and role functioning. The T-CGI-S score should be no more than mild (3), but in rare cases may be moderate (4) if the baseline severity was very high (7). If the T-CGI-S score is Normal (1), then the T-CGI-I score should be 1. |

| 2. Borderline ill | Symptoms are few in number and only intermittently present, and usually no more than mild severity. There is little or no interference in role functioning. | 2. Much improved | The patient has experienced clear and clinically meaningful reductions in symptoms, along with some improvement in role functioning, but distress or impairment from the illness persists. The T-CGI-S score should be no more than moderate (4), but in rare cases may be markedly ill (5) if the baseline severity was very high (7). |

| 3. Mildly ill | Symptoms are clearly present and cause distress, but there is only minimal or no reduction in functioning. | 3. Minimally improved | There is a detectable improvement in symptoms but little or no improvement in role functioning. The clinical significance of the changes is no more than minimal. |

| 4. Moderately ill | Symptoms are present every day or nearly every day but may diminish at times. Substantial distress is present but bearable. Functioning in important roles is somewhat reduced, or maintained only through high levels of perceived effort. Suicidal thoughts may be present, but there is usually a desire to live. | 4. No change | Symptoms and role functioning have not changed in any meaningful way since the baseline. |

| 5. Markedly ill | Symptoms are highly distressing and the patient struggles greatly to function in important life roles. Active suicidal ideation may be present. | 5. Minimally worse | There is a detectable worsening in symptoms but little or no change in role functioning. The clinical significance of the changes is no more than minimal. |

| 6. Severely ill | Symptoms are nearly constant and highly distressing, and the patient is unable to function in important life roles. Active suicidal ideation may be present. | 6. Much worse | Symptoms and role functioning are clearly worse from baseline. A change in treatment should be strongly considered. |

| 7. Among the most extremely ill patients | Symptoms are continuously present at a very severe level. The person is unable to maintain basic functioning. Active suicidal thoughts are usually present. Hospitalization is usually required. | 7. Very much worse | Symptoms and role functioning are dramatically worse than baseline. A change in treatment is definitely needed. |

| Complicated Grief CGI-S Moderately Ill (Score = 4) | T-CGI-S Moderately Ill (Score = 4) |

| Symptoms of complicated grief are present and intrusive on most days at a level that is painful but bearable. There is some interference with activities and relationships, but functioning is not substantially impaired. There may be some avoidance of reminders of the loss. A sense of purpose or meaning is usually present, but there may be confusion about this. Suicidal thoughts may be present, but there is usually a desire to live.Distraction is possible temporarily, but symptoms are persistent and clinically significant. | Symptoms are present every day or nearly every day but may diminish at times. Substantial distress is present but bearable. Functioning in important roles is somewhat reduced, or maintained only through high levels of perceived effort. Suicidal thoughts may be present, but there is usually a desire to live. |

| Complicated Grief CGI-I Much Improved (Score = 2) | T-CGI-I Much Improved (Score = 2) |

| There is evidence that distress and impairment from CG are definitely improved compared with baseline, and this improvement is definitely clinically significant. The patient notices some difference in the role grief plays in her/his life. The CG-CGI-S score is usually no more than moderate (4). However, a patient can be much improved and grief symptoms may still be marked (5) if the baseline severity was very high (7). | The patient has experienced clear and clinically meaningful reductions in symptoms, along with some improvement in role functioning, but distress or impairment from the illness persists. The T-CGI-S score should be no more than moderate (4), but in rare cases may be markedly ill (5) if the baseline severity was very high (7). |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dunlop, B.W.; Gray, J.; Rapaport, M.H. Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030040

Dunlop BW, Gray J, Rapaport MH. Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings. Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 7(3):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleDunlop, Boadie W., Jaclyn Gray, and Mark H. Rapaport. 2017. "Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings" Behavioral Sciences 7, no. 3: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030040

APA StyleDunlop, B. W., Gray, J., & Rapaport, M. H. (2017). Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings. Behavioral Sciences, 7(3), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030040