Work Ability in the Digital Age: The Role of Work Engagement, Job Resources and Traditional and Emerging Job Demands Among Older White-Collar Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

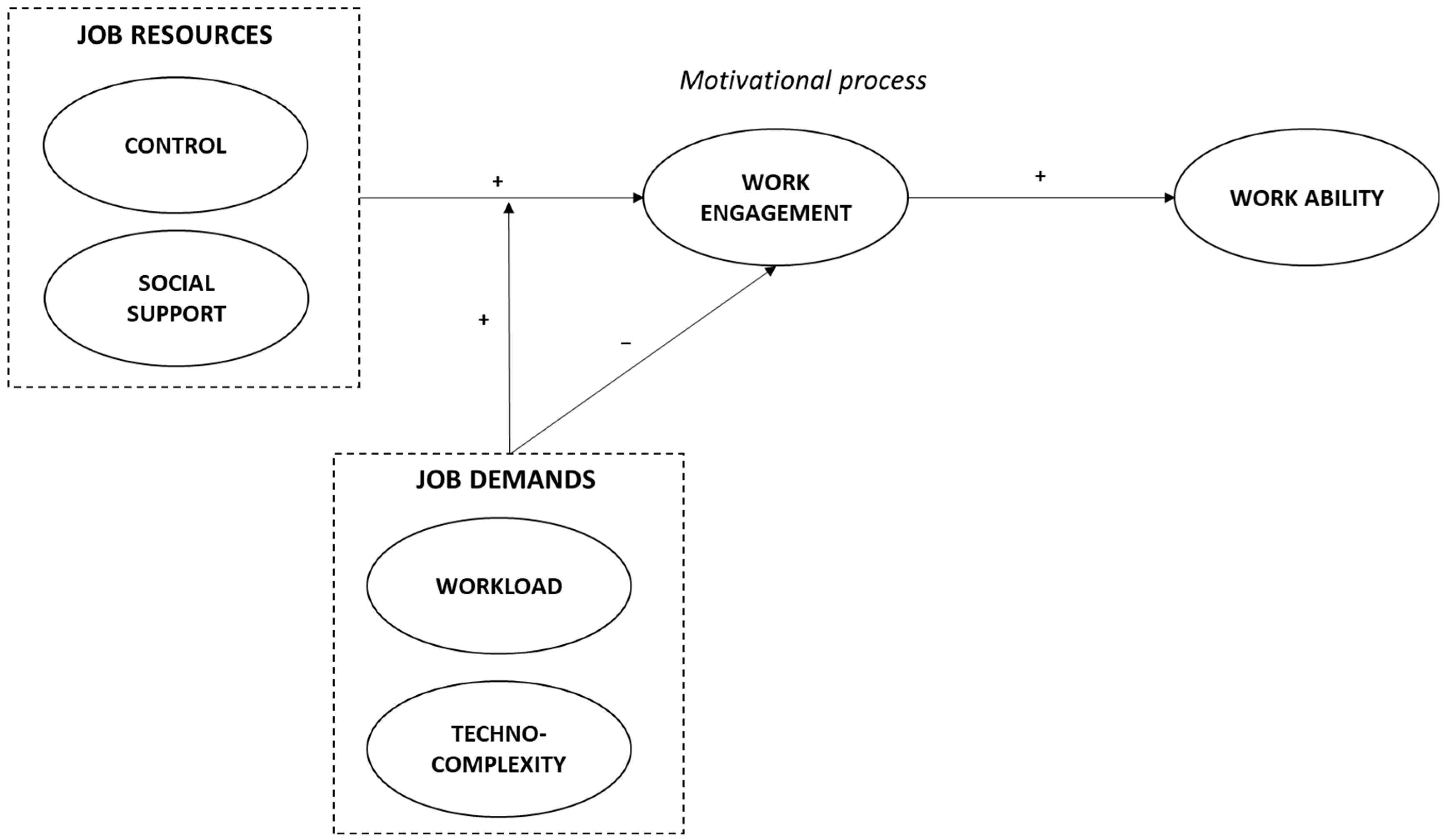

1.1. Work Ability, Work Engagement and Work Characteristics

1.2. Association Between Job Resources, Work Engagement and Work Ability

1.3. Association Between Job Demands, Work Engagement and Work Ability

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Measurement Model

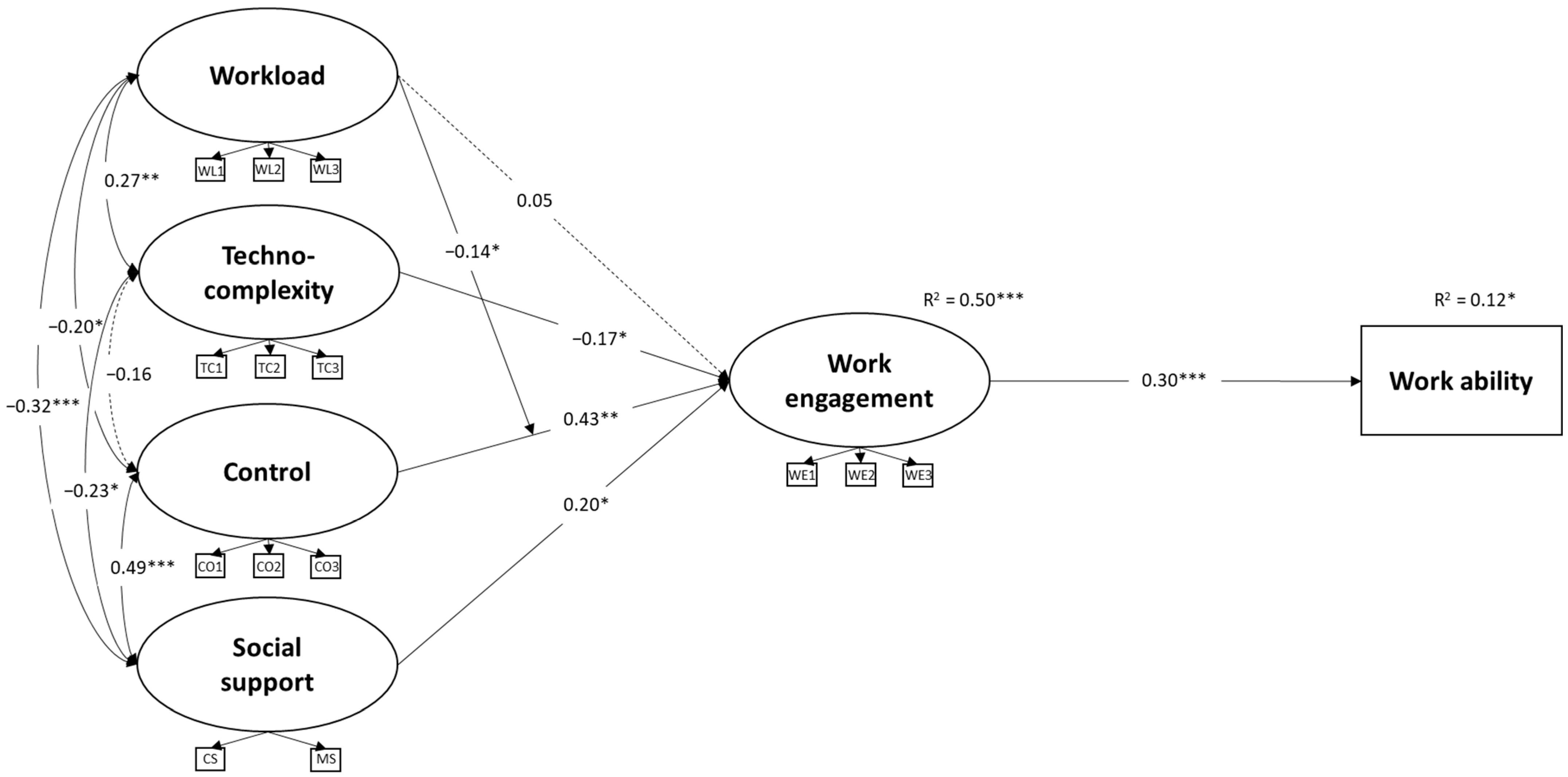

3.2. Mediation Model

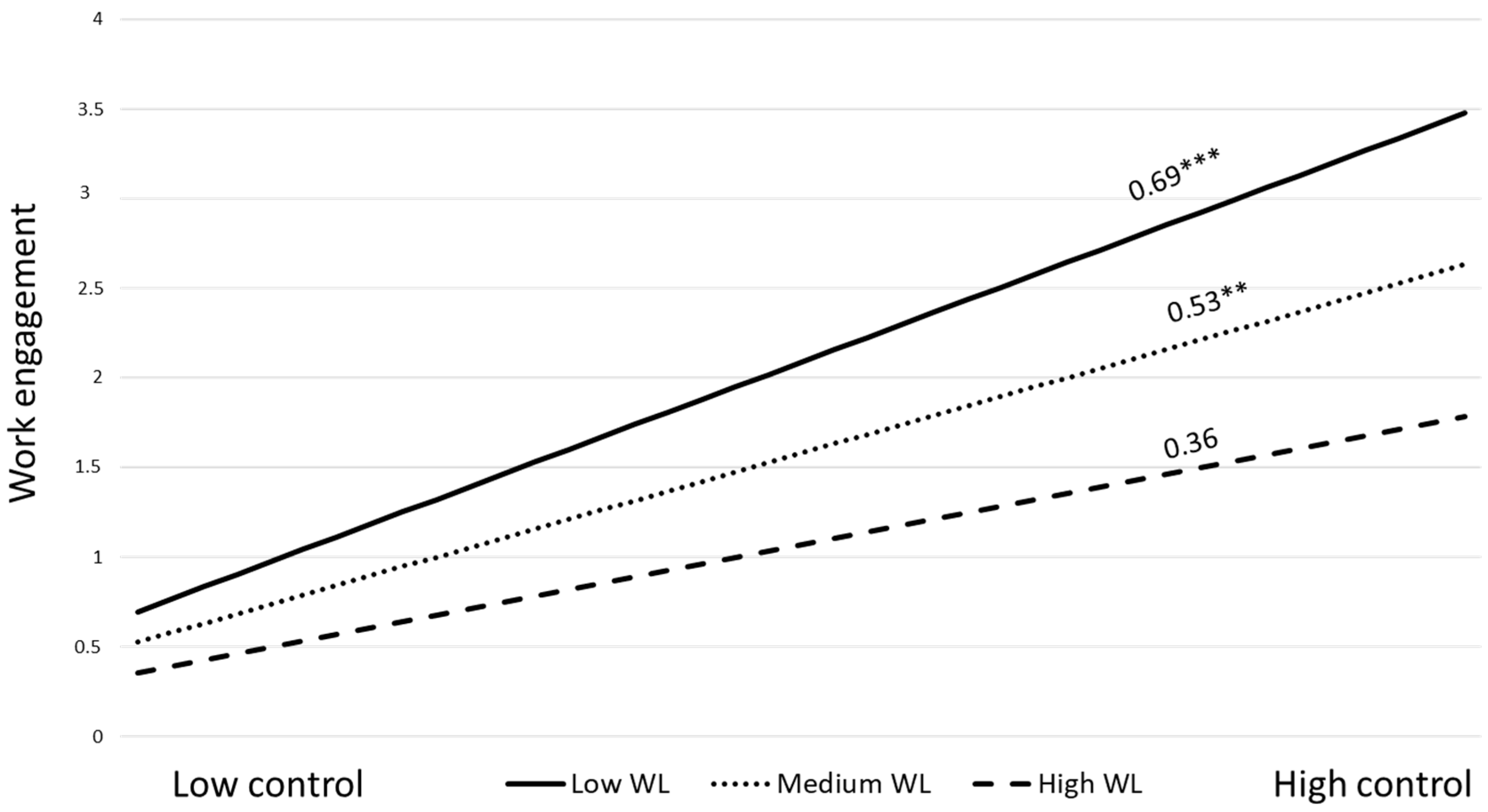

3.3. Moderated–Mediated Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| JD-R | Job Demands–Resources |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| MCAR | Missing Completely At Random |

| MS-IT | Management Standards Indicator Tool |

| UWES-3 | Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-3 items |

| WAI | Work Ability Index |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| FIML | Full Information Maximum Likelihood |

| YB | Yuan–Bentler |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| LMS | Latent Moderation Structural Equation Model |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| MLR | Robust Maximum Likelihood |

| 1 | Following the observations of an anonymous reviewer, we conducted a post hoc RMSEA-based power analysis to assess whether our sample size was adequate for the planned analyses using the web-based interface power4SEM (Jak et al., 2021). Specifically, with 107 degrees of freedom and a sample of 230 participants, power to reject the null hypothesis was 0.984 for RMSEA = 0.08 (hypothesis of close fit), 0.946 for RMSEA = 0.01 (hypothesis of not-close fit), and 0.963 for RMSEA = 0.00 (hypothesis of exact fit). These results indicate that the planned analyses could be reliably conducted. |

| 2 | Because our data were cross-sectional, we conducted an additional analysis by testing an alternative model in which workload, techno-complexity, control, and social support predicted work ability, which in turn predicted work engagement. However, this alternative model did not show an acceptable fit, as all goodness-of-fit indices indicated inadequate or poor model performance: YBχ2(107) = 225.765, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.873; TLI = 0.822; RMSEA = 0.069 (90% CI: 0.057–0.082; p < 0.01); SRMR = 0.095. These findings suggest that the model positioning work engagement as the mediator and work ability as the outcome provides a better fit for our data. |

References

- Airila, A., Hakanen, J. J., Punakallio, A., Lusa, S., & Luukkonen, R. (2012). Is work engagement related to work ability beyond working conditions and lifestyle factors? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 85(8), 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airila, A., Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., Luukkonen, R., Punakallio, A., & Lusa, S. (2014). Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagement. Work & Stress, 28(1), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides, & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling (pp. 243–277). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernburg, M., Vitzthum, K., Groneberg, D. A., & Mache, S. (2016). Physicians’ occupational stress, depressive symptoms and work ability in relation to their working environment: A cross-sectional study of differences among medical residents with various specialties working in German hospitals. BMJ Open, 6(6), e011369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blane, D., Netuveli, G., & Montgomery, S. M. (2008). Quality of life, health and physiological status and change at older ages. Social Science & Medicine, 66(7), 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonzini, M., Comotti, A., Fattori, A., Serra, D., Laurino, M., Mastorci, F., Bufano, P., Ciocan, C., Ferrari, L., Bollati, V., & Di Tecco, C. (2023). Promoting health and productivity among ageing workers: A longitudinal study on work ability, biological and cognitive age in modern workplaces (PROAGEING study). BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. A., Alarcon, G. M., Bragg, C. B., & Hartman, M. J. (2015). A meta-analytic examination of the potential correlates and consequences of workload. Work & Stress, 29(2), 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadiz, D. M., Grant, B., Rineer, J. R., & Truxillo, D. M. (2019). A review and synthesis of the work ability literature. Work, Aging and Retirement, 5(1), 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerino, D., Conway, P. M., Van der Heijden, B. I., Estryn-Behar, M., Consonni, D., Gould, D., Hasselhorn, H. M., & NEXT-Study Group. (2006). Low-perceived work ability, ageing and intention to leave nursing: A comparison among 10 European countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comotti, A., Fattori, A., Di Tecco, C., Bufano, P., Laurino, M., Mastorci, F., Russo, S., Barnini, T., Ferrari, L., Ciocan, C., & Bonzini, M. (2025). Cross-context validation of a technostress scale for the aging workforce. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 67(5), e347–e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converso, D., Viotti, S., Sottimano, I., Cascio, V., & Guidetti, G. (2015). Capacità lavorativa, salute psico-fisica, burnout ed età, tra insegnanti d’infanzia ed educatori di asilo nido: Uno studio trasversale [Work ability, psycho-physical health, burnout, and age among nursery school and kindergarten teachers: A cross-sectional study]. Medicina del Lavoro, 106(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debets, M., Scheepers, R., Silkens, M., & Lombarts, K. (2022). Structural equation modelling analysis on relationships of job demands and resources with work engagement, burnout and work ability: An observational study among physicians in Dutch hospitals. BMJ Open, 12(12), e062603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lange, A. H., Taris, T. W., Jansen, P. G. W., Smulders, P., & Houtman, I. L. D. (2006). Age as a factor in the relation between work and mental health: Results of the longitudinal TAS survey. In S. McIntyre, & J. Houdmont (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (Vol. 1, pp. 21–45). ISMAI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D. J., & Wall, T. D. (2002). Work characteristics, learning-related outcomes, and strain: A test of competing direct effects, mediated, and moderated models. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(4), 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, J. (2012, March 5). Promoting active ageing in the workplace [Internet]. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/promoting-active-ageing-workplace (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Ilmarinen, J. (2019). From work ability research to implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmarinen, J., & Ilmarinen, V. (2015). Work ability and aging. In L. M. Finkelstein, D. M. Truxillo, F. Fraccaroli, & R. Kanfer (Eds.), Facing the challenges of a multi-age workforce: A use-inspired approach (pp. 134–156). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ilmarinen, J., Tuomi, K., & Seitsamo, J. (2005). New dimensions of work ability. International Congress Series, 1280, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (2022, September 22). Previsioni della popolazione residente e delle famiglie [Internet]. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2022/09/REPORT-PREVISIONI-DEMOGRAFICHE-2021.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Jak, S., Jorgensen, T. D., Verdam, M. G. E., Oort, F. J., & Elffers, L. (2021). Analytical power calculations for structural equation modeling: A tutorial and Shiny app. Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. K., Latreille, P. L., Sloane, P. J., & Staneva, A. V. (2013). Work-related health risks in Europe: Are older workers more vulnerable? Social Science & Medicine, 88, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Karr-Wisniewski, P., & Lu, Y. (2010). When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U., & Nätti, J. (2018). Work ability score and future work ability as predictors of register-based disability pension and long-term sickness absence: A three-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(3), 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, C., Patterson, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, M. A. (2022). The challenge-hindrance stressor framework: An integrative conceptual review and path forward. Group & Organization Management, 47(2), 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocchi, I., Ghezzi, V., Di Tecco, C., Ronchetti, M., Ciampa, V., Olivo, I., & Barbaranelli, C. (2023). Demand–resource profiles and job satisfaction in the healthcare sector: A person-centered examination using Bayesian informative hypothesis testing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowsky, J., Jager, J., & Hemken, D. (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S., Ruokolainen, M., & Kinnunen, U. (2013). Does aging make employees more resilient to job stress? Age as a moderator in the job stressor–well-being relationship in three Finnish occupational samples. Aging & Mental Health, 17(4), 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G., Robledo, E., Vignoli, M., Topa, G., Guglielmi, D., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2023). Work engagement: A meta-analysis using the job demands-resources model. Psychological Reports, 126(3), 1069–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, A. K., Fisher, G. G., Barnes-Farrell, J. L., & Grosch, J. W. (2015). Individual and work factors related to perceived work ability and labor force outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (Version 8). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nastjuk, I., Trang, S. T.-N., Grummeck-Braamt, J., Adam, M. T. P., & Tarafdar, M. (2024). Integrating and synthesising technostress research: A meta-analysis on technostress creators, outcomes, and IS usage contexts. European Journal of Information Systems, 33(3), 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). The moderating effects of age in the relationships of job autonomy to work outcomes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 1(1), 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, G. (2018). Technostress: Measuring a new threat to well-being in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 22(8), 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, A. P., Taris, T. W., van Zolingen, S. J., & Schreurs, P. J. (2009). How task characteristics and social support relate to managerial learning: Empirical evidence from Dutch home care. The Journal of Psychology, 143(1), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Morgeson, F. P., & Johns, G. (2017). One hundred years of work design research: Looking back and looking forward. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L., & Chan, A. H. S. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between ageing and occupational safety and health. Safety Science, 112, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfírio, J. A., Felício, J. A., & Carrilho, T. (2024). Factors affecting digital transformation in banking. Journal of Business Research, 171, 114393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert-Kaźmierska, A., & Stankiewicz, K. (2016). Work–life balance: Does age matter? Work, 55(3), 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinone, B. M., Persechino, B., Castaldi, T., Valenti, A., Ferrante, P., Ronchetti, M., & Iavicoli, S. (2012). Work-related stress risk assessment in Italy: The validation study of health safety and executive indicator tool. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia, 34(4), 392–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rongen, A., Robroek, S. J., Schaufeli, W., & Burdorf, A. (2014). The contribution of work engagement to self-perceived health, work ability, and sickness absence beyond health behaviors and work-related factors. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(8), 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S. R., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2017). Integrating moderation and mediation: A structural equation modeling approach. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 721–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., & De Witte, H. (2019). An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The UWES-3 validation across five countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P. A., Delclos, G., Felknor, S. A., & Chosewood, L. C. (2019). Toward an expanded focus for occupational safety and health: A commentary. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawski, R. S., Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., & Smyth, J. M. (2008). Reported exposure and emotional reactivity to daily stressors: The roles of adult age and global perceived stress. Psychology and Aging, 23(1), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomietto, M., Paro, E., Sartori, R., Maricchio, R., Clarizia, L., De Lucia, P., Pedrinelli, G., Finos, R., & PN Nursing Group. (2019). Work engagement and perceived work ability: An evidence-based model to enhance nurses’ well-being. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(9), 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, K., Illmarinen, J., Jahkola, A., Katajarinne, L., & Tulkki, A. (2006). Work ability index (2nd ed.). Institute of Occupational Health. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Grelle, D. M. (2009). Alternative model specifications in structural equation modeling: Facts, fictions, and truth. In C. E. Lance, & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 165–191). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Doef, M., & Maes, S. (1999). The job demand-control (-support) model and psychological well-being: A review of 20 years of empirical research. Work & Stress, 13(2), 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, L., Leijten, F. R. M., Heuvel, S. G., Ybema, J. F., de Wind, A., Burdorf, A., & Geuskens, G. A. (2016). Company policies on working hours and night work in relation to older workers’ work ability and work engagement: Results from a Dutch longitudinal study with 2 year follow-up. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26(2), 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2014). Psychological research on retirement. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warr, P. (1993). In what circumstances does job performance vary with ages? European Work and Organizational Psychologist, 3(3), 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Future of jobs report. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2002). The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, B., Brzyska, M., Piłat, A., & Tobiasz–Adamczyk, B. (2022). Factors affecting work ability and influencing early retirement decisions of older employees: An attempt to integrate the existing approaches. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 35(5), 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K., Chan, W., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Robust transformation with applications to structural equation modelling. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 53(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacher, H., Kooij, D. T., & Beier, M. E. (2018). Active aging at work: Contributing factors and implications for organizations. Organizational Dynamics, 47(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | Sk | Ku | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Workload | 1.81 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.73 | |||||

| 2. Techno-complexity | 2.38 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.21 ** | 0.73 | ||||

| 3. Control | 3.69 | 0.66 | −0.91 | 1.69 | −0.15 * | −0.11 | 0.77 | |||

| 4. Social support | 4.04 | 0.41 | −0.32 | 3.94 | −0.26 *** | −0.17 ** | 0.36 *** | 0.83 | ||

| 5. Work engagement | 4.21 | 1.00 | −0.22 | −0.04 | −0.21 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.47 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.85 | |

| 6. Work ability | 44.74 | 2.90 | −1.29 | 2.93 | −0.13 | −0.24 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.25 *** | - |

| #Parameters | Log-Likelihood | AIC | Log-Likelihood Test | ΔAIC | Interaction Term | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 73 | −3981.784 | 8109.568 | - | - | - |

| Model 1a | 74 | −3978.762 | 8105.524 | 6.044 * | 4.044 | β = −0.14 * |

| Model 1b | 74 | −3980.651 | 8109.302 | 2.266 | 0.266 | β = −0.11 |

| Model 1c | 74 | −3981.466 | 8110.931 | 0.636 | −1.363 | β = −0.05 |

| Model 1d | 74 | −3980.060 | 8108.121 | 3.448 | 1.447 | β = −0.14 |

| Control → Work Engagement → Work Ability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Beta | p | ||

| Workload | Low (−1 SD) | 0.724 | <0.01 |

| Medium | 0.548 | <0.05 | |

| High (+1 SD) | 0.371 | 0.109 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Di Tecco, C.; Marzocchi, I.; Russo, S.; Comotti, A.; Fattori, A.; Laurino, M.; Bufano, P.; Ciocan, C.; Ferrari, L.; Bonzini, M. Work Ability in the Digital Age: The Role of Work Engagement, Job Resources and Traditional and Emerging Job Demands Among Older White-Collar Workers. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020191

Di Tecco C, Marzocchi I, Russo S, Comotti A, Fattori A, Laurino M, Bufano P, Ciocan C, Ferrari L, Bonzini M. Work Ability in the Digital Age: The Role of Work Engagement, Job Resources and Traditional and Emerging Job Demands Among Older White-Collar Workers. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(2):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020191

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Tecco, Cristina, Ivan Marzocchi, Simone Russo, Anna Comotti, Alice Fattori, Marco Laurino, Pasquale Bufano, Catalina Ciocan, Luca Ferrari, and Matteo Bonzini. 2026. "Work Ability in the Digital Age: The Role of Work Engagement, Job Resources and Traditional and Emerging Job Demands Among Older White-Collar Workers" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 2: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020191

APA StyleDi Tecco, C., Marzocchi, I., Russo, S., Comotti, A., Fattori, A., Laurino, M., Bufano, P., Ciocan, C., Ferrari, L., & Bonzini, M. (2026). Work Ability in the Digital Age: The Role of Work Engagement, Job Resources and Traditional and Emerging Job Demands Among Older White-Collar Workers. Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020191