Establishing Functional Communication Responses and Mands: A Scoping Review of Teaching Procedures and Implications for Future Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

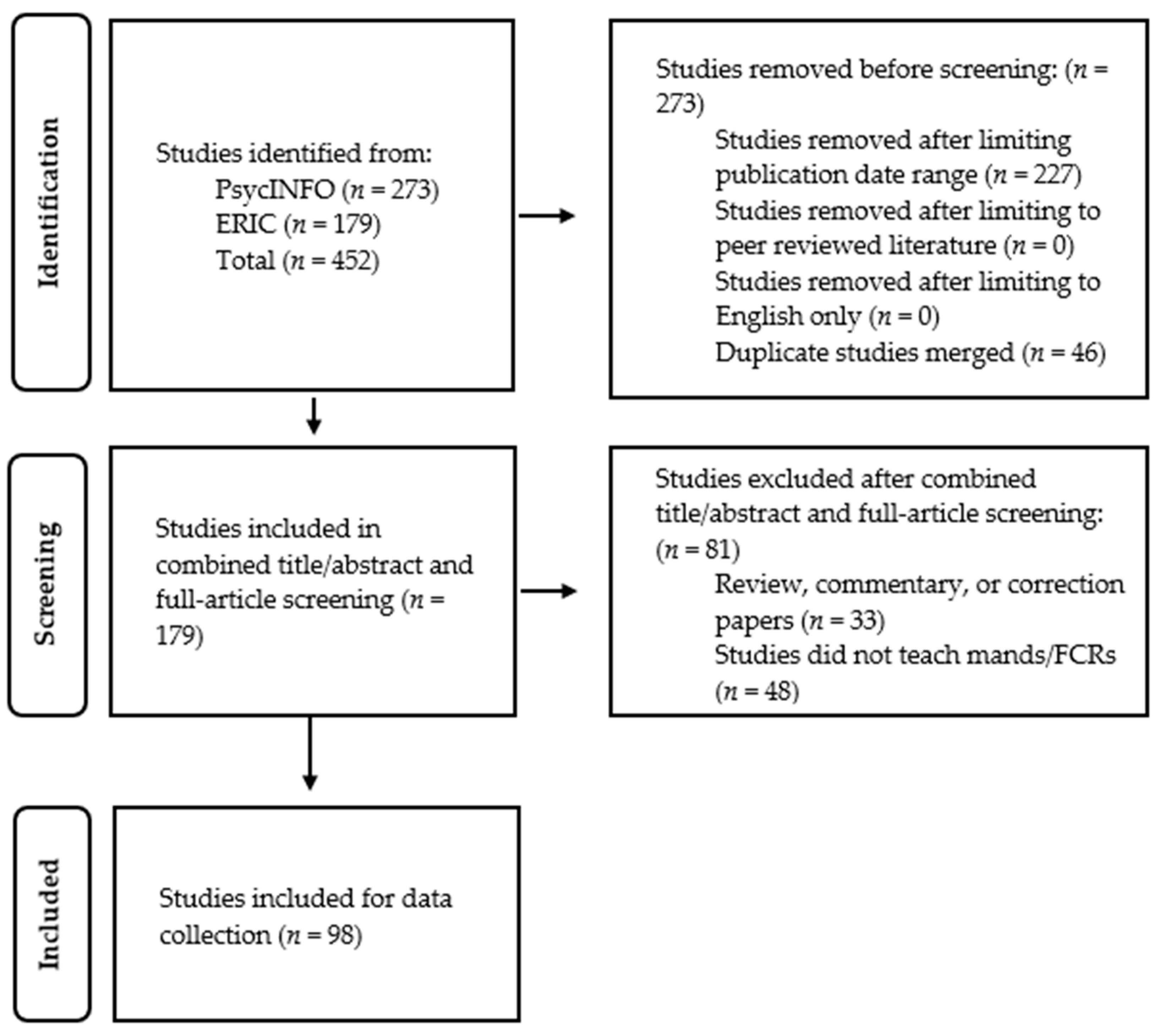

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Coding

2.4. Critical Appraisal of Sources

2.5. Interobserver Agreement

3. Results

3.1. Articles

3.2. Participants Setting

3.3. Behavior Reduction Information

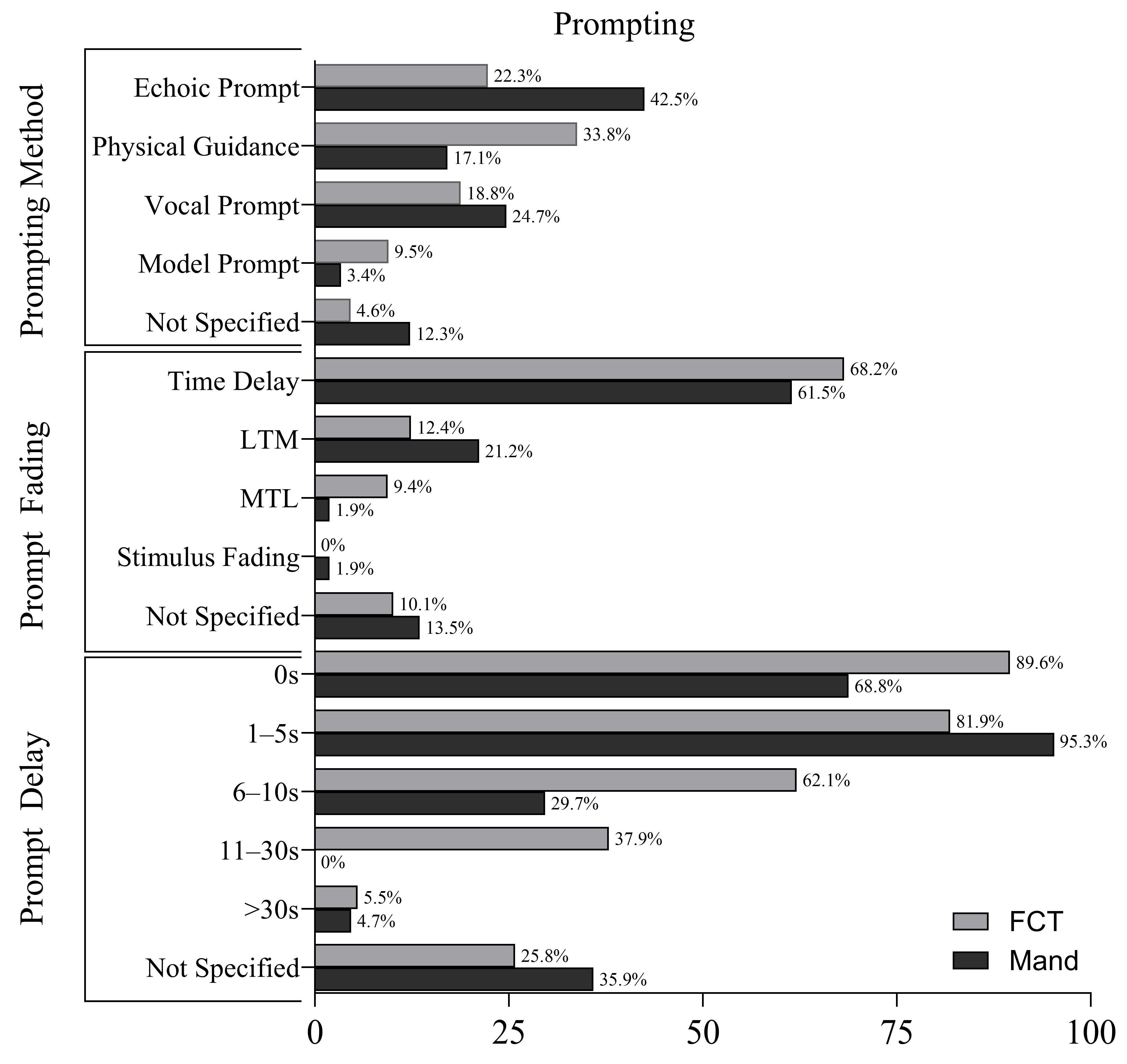

3.4. Prompting Methods

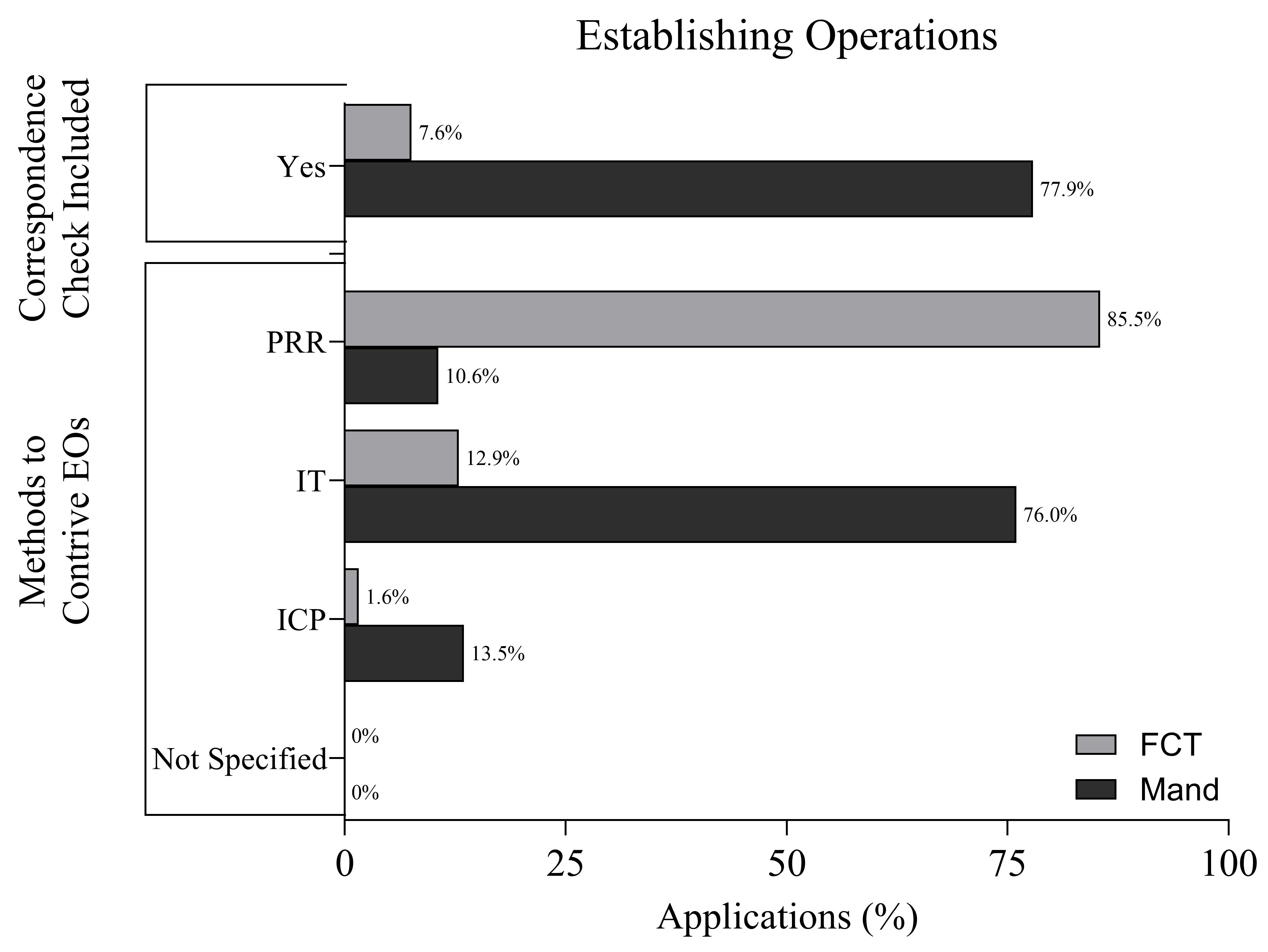

3.5. Establishing Operations

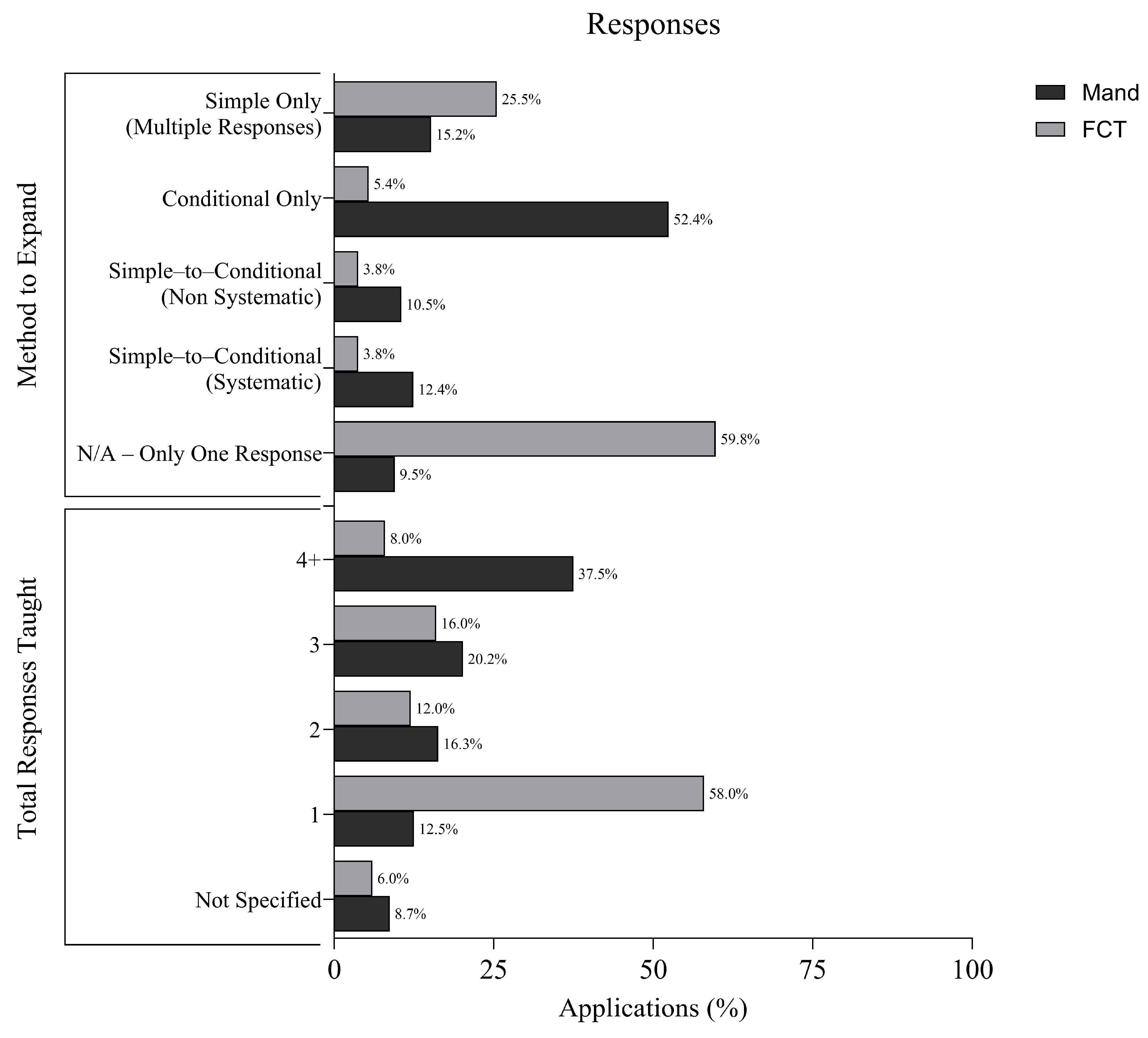

3.6. Number of Responses Taught

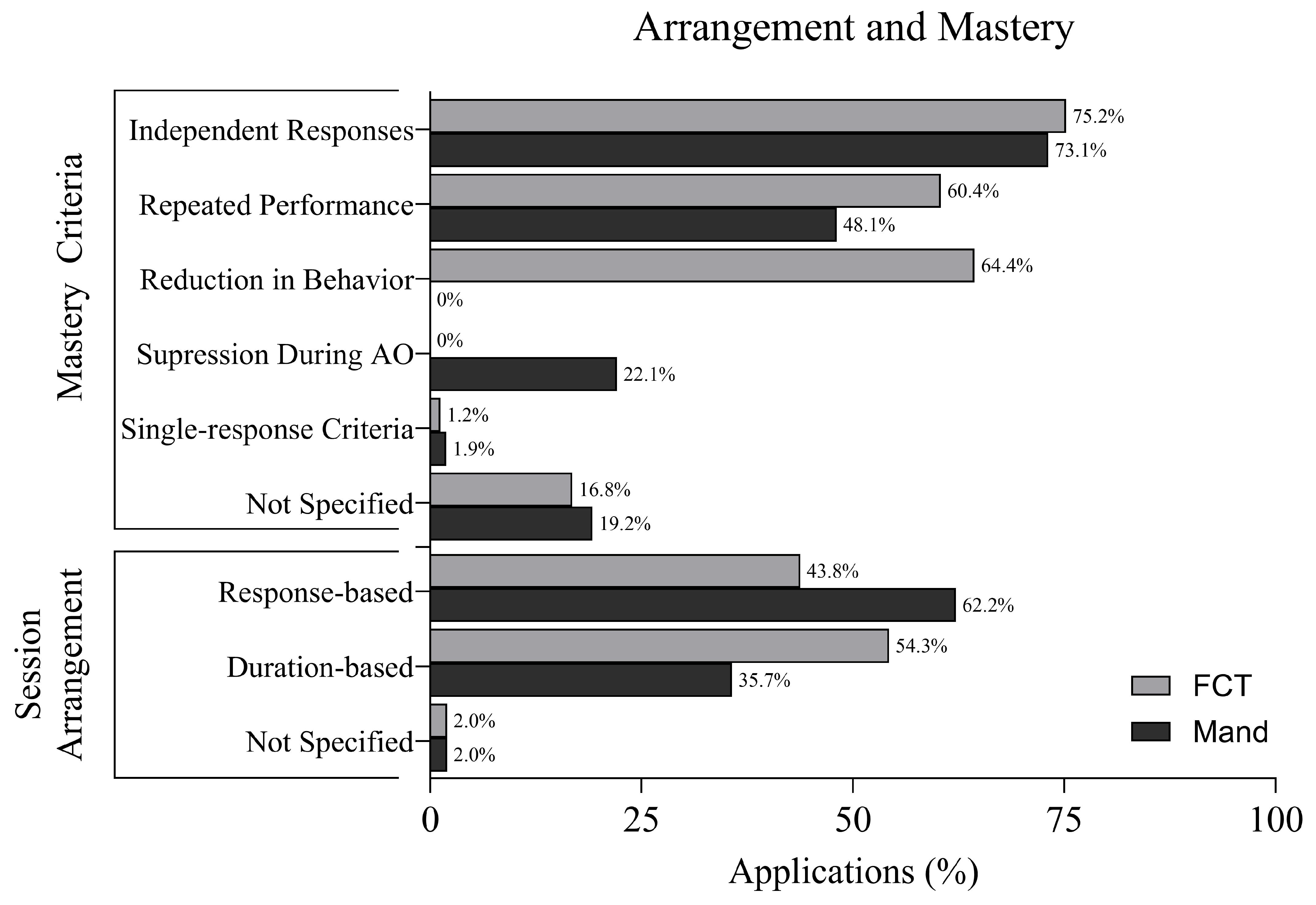

3.7. Session Arrangement and Mastery Criteria

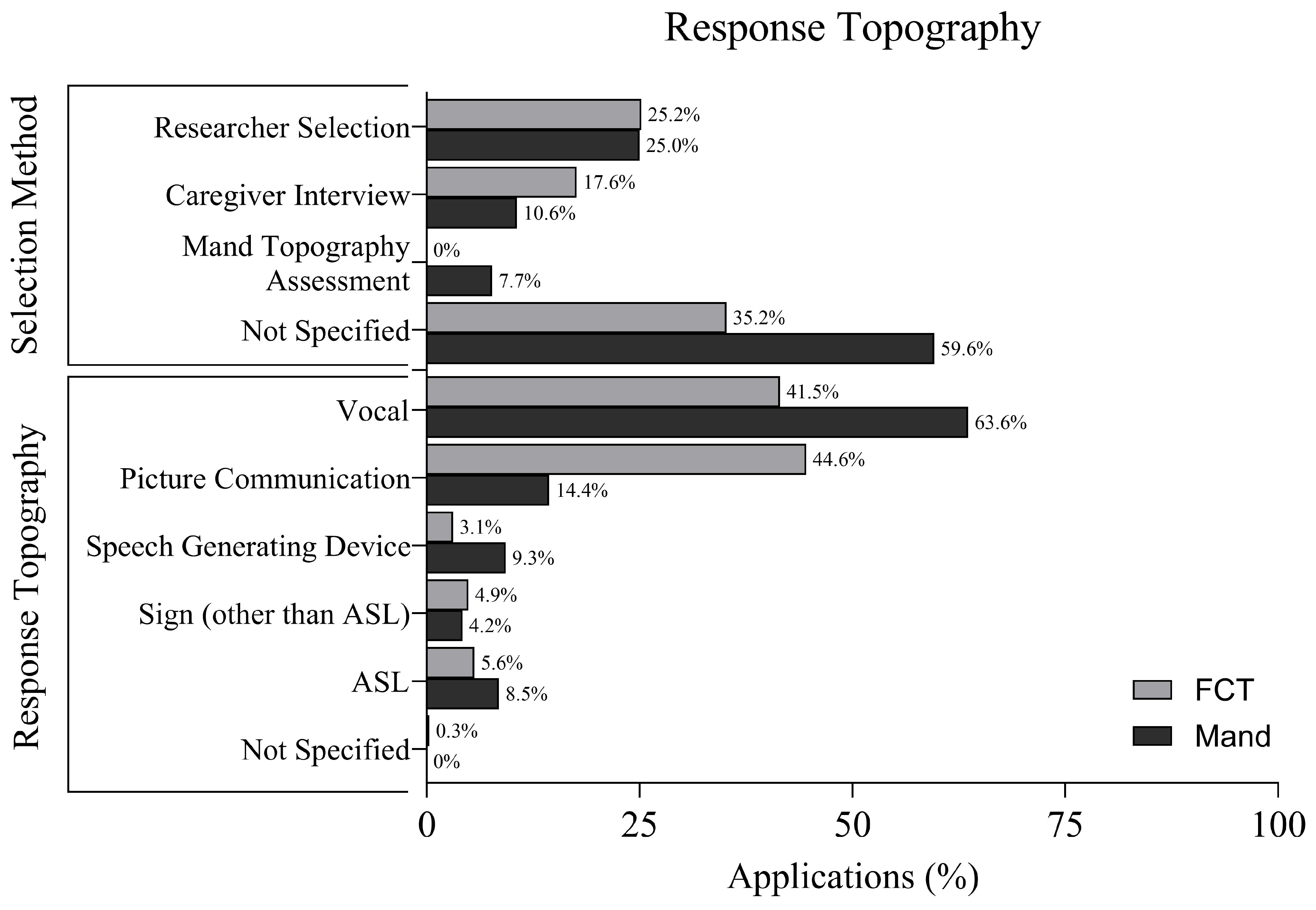

3.8. Response Topography and Selection Method

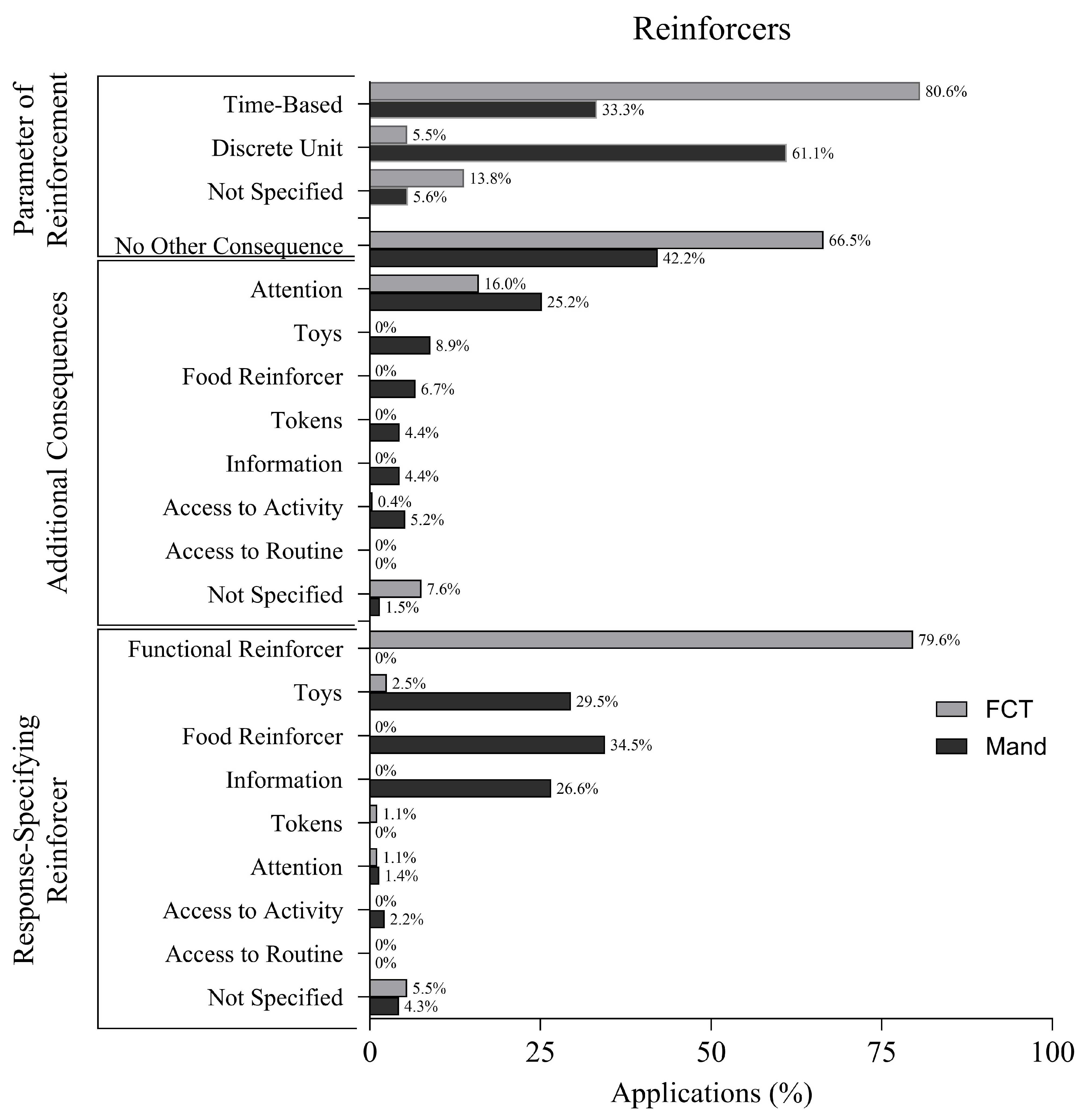

3.9. Parameters of Reinforcement

4. Discussion

4.1. Teaching Procedures

4.1.1. FCT

4.1.2. Mand Training

4.2. Comparison of Procedures

4.2.1. Similarities

4.2.2. Differences

4.3. Considerations for Future Research

4.3.1. Contriving EOs

4.3.2. Correspondence Between the EO and the Response

4.3.3. Number of Responses Taught

4.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MO | Motivating Operation |

| EO | Establishing Operation |

| AO | Abolishing Operation |

| FCR | Functional Communication Response |

| FCT | Functional Communication Training |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| IOA | Interobserver Agreement |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| IEP | Individualize Education Plan |

| PPVT | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test |

| VB-MAPP | Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program |

| EESA | Early Echoic Skills Assessment |

| ABLLS | Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills |

| ABLLS-R | Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills—Revised |

| EOWPVT | Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test |

| EVT | Expressive Vocabulary Test |

| PLS | Preschool Language Scale |

| FBA | Functional Behavior Assessment |

| ASL | American Sign Language |

| CMO-T | Transitive Conditioned Motivating Operation |

| FA | Functional Analysis |

| IISCA | Interview-Informed Synthesized Contingency Analysis |

Appendix A

Coding Instructions

- 1.

- FCT/Mand Training-Article Info form

- 2.

- FCT/Mand Training-Participant Info form

- If the article does not meet the criteria (indicated by an answer containing “(exclude)”), answer “yes” to the final question, submit the response, and stop there.

- For excluded articles, do not complete the Participant Info form.

- Provide general information about the article, such as the author, publication date, and title.

- ∘

- Tip: Copy the article title after typing it into the form. You’ll need to paste it exactly as written into the Participant Info form for consistency.

- Answer questions about the procedures:

- ∘

- If all participants had the same procedure for a given component, select that component (or components).

- ∘

- If procedures differed among participants for a given component, select “Procedure Varied By Participant.”

- Paste the article title (copied from the Article Info form) into the form to ensure consistency. This helps organize the data.

- Provide information specific to each participant. For example, if the study had five participants, you will submit five separate Participant Info forms.

- Select “Yes” if you indicated the procedures varied by participant at any point when completing the Article Info form.

- If “Yes” is selected, please complete the entire form for each participant.

- Refer to the operational definitions below for guidance on answering questions and interpreting responses.

- If you have any questions while completing the forms, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me for clarification.

Appendix B

Coding Operational Definitions

| FCT/Mand Training-Article Info Forms | ||

| Section 1: Article Information | ||

| Question: | Response | Operational Definition |

| Your Name | Input your name | |

| Primary or Reliability Data | Primary | Primary data collector, as indicated by PI |

| Reliability | Interrater agreement data collector, as indicated by PI | |

| First author’s last name and first initial | Input the author’s last name and initial of first name separated by a comma | |

| Year of Publication | Select the year that the article was published in the journal | If the article has been published online and in print, input the in-print year; If the article is only published as an online version, input the online publication year |

| Article Title | Write the article title in its entirety. Title case is not necessary | |

| Was the article published in or after 2014? | Yes | The article publication year (either in print or online) is 2014–2024; if the article was available online before 2014 but available in print in 2014 or later, select “yes” |

| No (exclude) | The article publication year is 2013 or earlier | |

| Was the article published in a peer-reviewed journal? | Yes | Non-peer reviewed journals were ruled out during search, so any study published in a journal will be from a peer-reviewed journal |

| No (exclude) | The article was not published in a journal. Examples include invited talks, unpublished theses or dissertations | |

| Was the article written in a language other than English? | Yes (exclude) | |

| No | ||

| Did the article describe the teaching procedures (e.g., prompting procedure, reinforcement schedule) of at least one FCR/Mand? | Yes | |

| No (exclude) | ||

| Does the article describe a single-subject study that manipulated at least one independent variable and measured at least one dependent variable (i.e., not a review or discussion paper)? | Yes | The authors manipulated an independent variable for one or more participants and data are reported on dependent variable(s) using a single-subject research design. |

| No (exclude) | The study incorporated a group design (e.g., experimental group and control group) or was a non-experimental study. Examples of non-experimental studies include descriptive studies (i.e., collection of observations without manipulating an IV), review papers, or theoretical papers. | |

| Number of participants | Participants are defined as the number of individuals who received either mand training or FCT. Participants do not include caregivers, teachers, or staff members who were trained to implement FCT or mand training. | |

| Did any of your responses indicate to exclude this article? | Yes | |

| No | ||

| Section 2: General Procedures | ||

| Question: | Response | Operational Definition |

| Was challenging behavior reduction targeted in the study? | Yes | The article described a response topography that was targeted for reduction with the use of a functional communication response. Examples of behaviors include aggression, pica, disruptive behavior. |

| No | ||

| Unsure | ||

| If yes (or unsure, if applicable), what components of functional behavior assessment(s) were used? If challenging behavior was not targeted, skip this question and move to the next question. (Select all that apply) | Indirect (e.g., interview) | Asking questions about the behavior of interest without directly observing the behavior. Examples include the FAST or Open-Ended Interview. |

| Direct Observation (e.g., ABC Data, Structured Observation) | Implementers directly observed the behavior of interest by did not systematically manipulate antecedent and consequent events. Examples include ABC data collection, structured observations, or scatterplots. | |

| Experimental Analysis (e.g., FA, IISCA) | Implementers systematically manipulate antecedent and/or consequent events. Will include at least one test condition and a control condition. | |

| N/A | Select if challenging behavior reduction was not targeted in the study | |

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Method for selecting FCR/Mand topography (Select all that apply) | Mand Topography Assessment (Experimental) | Experimental assessment used to systematically identify preference for or efficiency of FCR/Mand topographies |

| Caregiver Interview | Can include a formal or informal interview with a caregiver or other relevant stakeholder. Only score if article specifically states that the caregiver selected or informed the mand topography | |

| Therapist/Researcher Selection | Score if the article specifically states that the therapist or researcher selected the FCR/Mand topography | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Mastery criteria for FCR/Mand acquisition (Select all that apply) | Reduction in Challenging Behavior (e.g., 80% decrease from baseline, less than 20% of trials) | A reduction in challenging behavior was required to determine mastery of the FCR/Mand. This option can be selected in combination with other options. |

| Increase in Independent FCR/Mand (e.g., above 80% correct independent) | Mastery is determined by the number of correct or independent FCRs/Mands. Does not include other types of responses such as indicating responses or correspondence checks. This option can be selected in combination with other options. | |

| Single-Response Criteria (e.g., correct response in cold probe, correct first-trial responding) | Mastery is determined by a single response, typically defined as the first opportunity to respond following a certain time frame. Examples include cold probes (i.e., first trial in a given day) or correct first-trial responding (i.e., first trial in a trial block) | |

| Repeated performance over a set number of trials/sessions | Select if the mastery criteria requires repeated performance of the response over a specified number of trials or sessions. Example: 100% correct responding over three consecutive sessions | |

| Suppressed responding during AO trials (e.g., less than 33% of sessions; differentiated responding) | Select if the authors used AO trials during teaching and included a requirement for differentiated responding between EO and AO trials. The authors will indicate that mastery criteria required zero or a low amount of responses during AO trials. | |

| Not Specified/Unknown | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Number of FCRs/Mands targeted from throughout the study | 1 | Select the total number of FCRs/Mands that were targeted throughout the study. Not all FCRs/Mands need to be taught simultaneously (e.g., an array of 3 FCRs/Mands taught across phases or introduced sequentially); score the total number of distinct FCRs/Mands targeted for the participant. Count each FCR/Mand as distinct if it differs by:

|

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4+ | ||

| Not Specified | Score if the article did not describe the number of responses targeted from the onset of procedures and did not describe a teaching procedure that allowed for free-operant responding (e.g., discrete trial instruction) | |

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| If distractors were used, how many distractors were used at the onset of the procedures? | 0 | Only score if selection-based responses (e.g., card exchange, card touch, PECS) were targeted and distractors (i.e., non-targeted responses or stimuli). Select the number of additional cards (i.e., all cards not targeted as a FCR/Mand) used as distractors at the onset of teaching. Distractors can be blank cards, cards displaying neutral or non-preferred items, or non-targeted preferred items. Select “0” if distractors were used during procedures but not during the onset of training (e.g., one target response w/o distractors at onset and eventually added blank distractors to the array). |

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3+ | ||

| N/A—Distractors Were Not Used | Select if selection-based responses were not targeted (e.g., vocal, signs) or if distractor cards were not used despite the use of a selection-based topography | |

| Not Specified | Select if the article indicates that distractors were used, but did not indicated the number of distractors used at the onset of teaching | |

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| If distractors were used, what type of distractor cards were used | Blank cards (any color) | Distractor cards did not have any pictures, symbols, words, etc. and were blank. The color of the card (e.g., white distractor card, black distractor card) did not matter |

| Low-preferred or neutral items | Distractor cards included pictures of other items, but the corresponding items were low- or neutral-preferred. Experimenters may have described a systematic test to identify value (e.g., preference assessment) or arbitrarily selected the items | |

| N/A—Distractors Were Not Used | Select if selection-based responses were not targeted (e.g., vocal, signs) or if distractor cards were not used despite the use of a selection-based topography | |

| Not Specified | Select if the article indicates that distractors were used, but did not describe the distractor | |

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Method to Increase FCR/Mand Repertoire | Teach each FCR/Mand in isolation as a simple discrimination (no conditional discrimination targeted) | Select if authors only taught a series of simple discriminations and never included all FCRs/Mands in a conditional discrimination. If the topography was vocal, select this option if the authors only arranged EOs for one FCR/Mand at a time. |

| Teach each FCR/Mand in isolation and then combine all FCRs/Mands | Select if authors only taught each FCR/Mand in isolation as a simple discrimination and then combined all FCRs/Mands. For example, teaching juice, milk, and water individually and then combining all three into an array. This excludes teaching FCRs/Mands in isolation and then systematically introducing FCRs/Mands into an array. | |

| Teach one FCR/mand in isolation and then systematically add new FCRs/mands (conditional discrimination) | Select if authors initially taught one FCR/Mand in isolation and then systematically added one or more into the array/discrimination. | |

| Target all FCRs/Mands from the onset of training | All FCRs/Mands were targeted at the onset of training as a conditional discrimination. Can include two or more requests. Will also include teaching two or more requests as a conditional discrimination and then teaching additional requests later. | |

| N/A—only one FCR/Mand was taught | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Method to Contrive EOs (Select all that apply) | Incidental Teaching | The EO was captured or contrived within the natural environment, often by placing a reinforcer in view but out of reach or interrupting access to an item the participant is currently engaging with. Mand opportunities are created by brief environmental manipulations or responses to participant behavior (e.g., reaching, pointing) rather than structured task demands. Examples: toy on high shelf, brief removal of preferred item, hiding materials mid-play. |

| Interrupted Chains Procedure | The EO was contrived by interrupting a well-established behavior chain in which one or more components are missing, broken, or inoperable. The interruption creates a conditioned EO (CEO-T) by making a specific item or action necessary to complete the chain and access a terminal reinforcer. Examples: spoon missing from soup routine, puzzle piece removed, toy without batteries. | |

| Programmed Restriction of Reinforcers | The EO was contrived by systematically withholding access to a known reinforcer for a programmed duration (e.g., minutes, hours, days), regardless of context. The mand is evoked without any direct cues for item availability and occurs under deprivation rather than task interruption. Examples: withholding tablet or snack before session, storing preferred items out of sight until FCR occurs | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Prompting Type (Select all that apply) | Echoic Prompt | Therapist engages in an antecedent vocal-verbal response that shares formal similarity (i.e., both spoken) and point-to-point correspondence. Also include echoic prompts that are partial echoic prompts (i.e., antecedent response was only part of the targeted response). |

| Vocal Prompt | Therapist provides an antecedent vocal-verbal response that shares formal similarity but does not include point-to-point correspondence. Examples include reminding the participant of the contingencies (“if you want something, you can touch the card”) or providing vocal statements following an indicating response (“what do you want?”) | |

| Model Prompt | Therapist demonstrates how to complete the target response or uses their body to gesture towards the completion of a response. This is a “show” prompt, where the therapist does not use vocal behavior or physical guidance to have the participant complete the instruction | |

| Physical Guidance | Therapist prompts the participant using any level of physical guidance (e.g., hand-over-hand, graduated guidance). Physical prompting should be scored if the therapist touches the participant in any way to prompt them towards completing the instruction. | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Prompt Fading Procedure (Select all that apply) | Most-to-Least Prompting | Therapists started with the most intrusive prompt (e.g., physical guidance, full vocal model) and then systematically decreases the level of prompting. Note: most-to-least prompting only changes the type of prompt used, not the time until a prompt. If a time delay is included, select Time Delay |

| Least-to-Most Prompting | Therapists started with a lesser intrusive prompt and then systematically increased the level of prompting following errors or no-responses. Sometimes referred to as “three-step prompting” or “three-step guided compliance” | |

| Time Delay (e.g., fixed-time, progressive-time) | Teaching starts with the simultaneous presentation of the start of a trial (e.g., removal of item, blocked response) and the prompt. A delay is then inserted to increase the time between the start of the trial and prompt. Time delay can either be progressive (i.e., prompt delay continues to increase) or constant (i.e., once the delay is inserted, the delay remains the same) | |

| Stimulus Fading | Some feature of the prompt (e.g., salience) is systematically reduced to transfer stimulus control from the prompting stimulus to naturally occurring discriminative stimuli | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Prompt Delay or Duration of EO (Select all that apply) | 0 s | A prompt delay is the amount of time between the discriminative stimulus and the prompt. For example, a preferred item is removed and the therapist waits 10 s for the participant to emit a response. Select all prompt delay durations that were used in the study. Select only the prompt delay to the teaching of the FCR or mand and not to other responses. |

| 1–5 s | ||

| 6–10 s | ||

| 11–30 s | ||

| Greater than 30 s | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Response Specifying Reinforcer Provided (i.e., what did the participant mand for?) | Functional Reinforcer (i.e., same reinforcer that maintains challenging behavior) | Select if challenging behavior reduction was targeted and the reinforcer for the FCR was the same reinforcer that maintained challenging behavior, as indicated by the FBA |

| Non-Functional Reinforcer (Challenging behavior still targeted but FCR was for a reinforcer that maintains target behavior) | Select if challenging behavior reduction was targeted, but the reinforcer for the FCR was different from the reinforcer maintained challenging behavior, as indicated by the FBA. If both a functional and nonfunctional reinforcer was provided for FCRs, select both options. | |

| Toys | Select the appropriate reinforcer type only if challenging behavior was not targeted for reduction. Select only the reinforcer that was specified in the mand (i.e., mand-specifying reinforcer) and not and additional reinforcers provided following the mand. | |

| Food-Based | ||

| Attention | ||

| Tokens | ||

| Information | ||

| Access to Routine | ||

| Access to Activity | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| What Additional Consequences Were Provided Along with the EO-Related Reinforcer | See above for options and operational definitions | |

| Parameter of Reinforcement (Select all that apply) | Time-based | Select if authors described a time-based parameter of reinforcement, such as 30-s access to an item or remainder of trial. Selection of time-based indicates that the researcher takes away, or is able to take away, the reinforcers after a set duration of time. If the authors describe reinforcement as “brief access to (e.g., 3–5 s)”, select a time-based parameter. |

| Discrete Unit | Select if the reinforcer was a discrete unit of reinforcement instead of being based on an amount of time. Examples: one skittle, information, a statement on praise). If the authors describe reinforcement as “brief access to (e.g., 3–5 s)”, select a time-based parameter. | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Was a method to check correspondence (e.g., correspondence check, indicating response, measure of consumption) between the EO and the mand included? | Yes | Select if the authors included a method to check correspondence between the EO and the mand. Methods can include an indicating response (therapists waited until participant showed interest in the reinforcer), correspondence check (therapist had participant select the item from an array following the mand to ensure the mand and selected item matched), or measure of consumption (authors measured if the participant consumed the reinforcer) |

| No | No method to check correspondence was used. | |

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| Session Arrangement | Duration-Based Sessions (e.g., 10-min session) | Data were collected during sessions that were based on a session duration. The session lengths could vary, but were not defined by the number trials or requests during the session |

| Response-Based Sessions (e.g., 10 trials) | Sessions were defined by the number of opportunities to emit a response (i.e., trials) and not based on a duration of session. | |

| Not Specified | ||

| Procedure Varied by Participant | Select if one or more of the participants had differing procedures. | |

| FCT/Mand Training-Participant Info Forms | ||

| Section 2: Participant Information | ||

| Question: | Response | Operational Definition |

| Participant Name | ||

| Age of Participant (in years) If both years and months were reported, round the months to the nearest year (e.g., 11 years and 3 months to 11 years, 5 years and 10 months to 6 years) | ||

| Participant Diagnoses (select all that apply) | Autism Spectrum Disorder (aka Autistic, Autism, ASD, Autistic Disorder) | |

| Developmental Disability (e.g., Down Syndrome, Global Developmental Delay) | ||

| Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD [other names include ADD]) | ||

| Dementia or other Degenerative Disorder | ||

| No Diagnoses | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Assessment(s) of Language/Communication | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) | |

| Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP) | ||

| Early Echoic Skills Assessment (EESA) | ||

| VB-MAPP Intraverbal Assessment Subtest | ||

| Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (ABLLS or ABLLS-R) | ||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale | ||

| Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT) | ||

| Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT) | ||

| Preschool Language Scale (PLS) | ||

| Information on Number of Mands | ||

| Information on Sentence Length (e.g., 1-to-2 word sentences) | ||

| Information from IEP | ||

| None Reported | ||

| What were the reported scores? Please provide the score exactly as it was reported in the article. You can use a direct quote to report scores. If multiple assessments or scores were reported, separate them by using a semicolon (If no information was provided on language, type in N/A) | ||

| FCR/Mand Topography | Vocal | |

| Picture Communication (e.g., picture exchange, card touch) | ||

| Speech Output Device (e.g., tablet with Dynavox, Bigmac Button) | ||

| Sign (i.e., not ASL; e.g., modified signs) | ||

| ASL | ||

| Pointing/Gestures | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Therapy Setting | Clinic (outpatient) | |

| School | ||

| Home | ||

| Hospital (inpatient) | ||

| Institution (Group home, Nursing home) | ||

| Vocational Program | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Section 3: Participant Challenging Behavior Information | ||

| Question: | Response | Operational Definition |

| Topography(ies) of Behavior Targeted with Intervention | Aggression | |

| Self-injury | ||

| Disruptions/Property Destruction | ||

| Negative Vocalizations | ||

| Stereotypic Behavior (Vocal or Motor) | ||

| Tantrums | ||

| Inappropriate Mealtime Behavior | ||

| Elopement | ||

| Noncompliance | ||

| Pica | ||

| Enuresis or Encopresis | ||

| Rumination and/or Operant Vomiting | ||

| Dangerous Behavior (e.g., setting fires, climbing) | ||

| Function(s) of Behavior Targeted with Intervention | Attention | |

| Tangible | ||

| Escape | ||

| Automatic | ||

| Synthesized | ||

| Social Control (also called mand compliance, adult compliance with mands, request compliance, compliance with requests, adult-directed play, escape to child-directed play) | ||

| Access to Ritualistic Behavior (e.g., arranging and ordering) | ||

| Not Specified | ||

| Functional Behavior Assessment Type | Indirect (e.g., interview) | Asking questions about the behavior of interest without directly observing the behavior. Examples include the FAST or Open-Ended Interview. |

| Direct Observation (e.g., ABC Data, Structured Observation) | Implementers directly observed the behavior of interest by did not systematically manipulate antecedent and consequent events. Examples include ABC data collection, structured observations, or scatterplots. | |

| Experimental Analysis (e.g., FA, IISCA) | Implementers systematically manipulate antecedent and/or consequent events. Will include at least one test condition and a control condition. | |

| Not Specified | ||

| None | ||

| Section 4: Participant FCT/Mand Training Variations | ||

| Question: | Response | Operational Definition |

| Did you select “Procedure Varied by Participant” for any of the responses in the FCT/Mand Training-Article Info survey? | Yes | |

| No | ||

References

- Akers, J. S., Retzlaff, B. J., Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Kaminski, A. J., & DeSouza, A. A. (2019). An evaluation of conditional manding using a four-component multiple schedule. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 35(1), 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. R., Zangrillo, A. N., & Greer, B. D. (2021). Development of a systematic approach to identify reinforcer dimension sensitivity. Behavioral Development, 26(2), 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18(2), 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRosa, N. M., Fisher, W. W., & Steege, M. W. (2015). An evaluation of time in establishing operation on the effectiveness of functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L. M. (2019). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Fifth edition (PPVT-5) [Measurement instrument]. NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Esch, B. E. (2014). Early Echoic Skills Assessment (EESA) [Measurement instrument]. AVB Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Mitteer, D. R., Fuhrman, A. M., Romani, P. W., & Zangrillo, A. N. (2018). Further evaluation of differential exposure to establishing operations during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(2), 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, S. E., Axe, J. B., Davis, C. R., Meleshkevich, O., & Li, M.-H. (2024a). A tutorial on indicating responses and their importance in mand training. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(4), 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, S. E., Davis, C. R., Meleshkevich, O., & Axe, J. B. (2024b). A clinical tutorial on methods to capture and contrive establishing operations to teach mands. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(4), 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, B. D., Fisher, W. W., Saini, V., Owen, T. M., & Jones, J. K. (2016). Functional communication training during reinforcement schedule thinning: An analysis of 25 applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(1), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grow, L., & LeBlanc, L. (2013). Teaching receptive language skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 6(1), 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, G., Jin, C., Vanselow, N., & Hanratty, L. (2014). Producing meaningful improvements in problem behavior of children with autism via synthesized analysis and treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnavatana, S. S., Wolfe, K., & Aguilar, A. N. (2018). Assessing mand topography preference when developing a functional communication training intervention. Behavior Modification, 42(3), 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, P. F., Leoni, M., & Hagopian, L. P. (2020). Behavioral approaches to assessment and early intervention for severe problem behavior in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 67(3), 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landa, R. K., Hanley, G. P., Gover, H. C., Rajaraman, A., & Ruppel, K. W. (2022). Understanding the effects of prompting immediately after problem behavior occurs during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(1), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, D. C., Hawkins, L., Hillman, C., Shireman, M., & Nissen, M. A. (2015). Adults with autism spectrum disorder as behavior technicians for young children with autism: Outcomes of a behavioral skills training program. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(2), 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, C. P., Tran, J. P., Charles, B. M., Jeglum, S. R., Luehring, M. C., & Kurtz, P. F. (2024). Comparison of mand acquisition and preference in children with autism who exhibit problem behavior. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 37(3), 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N. A., & Brownell, R. (2011). Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—Fourth edition (EOWPVT-4) [Measurement instrument]. Pro-Ed (or Academy Therapy Publications). [Google Scholar]

- McGill, P. (1999). Establishing operations: Implications for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(3), 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions of stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 37(1), 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J. (1993). Establishing operations. The Behavior Analyst, 16(2), 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partington, J. W. (2010). The Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills—Revised (The ABLLS-R): An assessment, curriculum guide, and skills-tracking system for children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Behavior Analysts, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Partington, J. W., & Sundberg, M. L. (1998). The Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills (The ABLLS): An assessment, curriculum guide, and skills-tracking system for children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Behavior Analysts, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Hagopian, L. P., Bowman, L. G., & Toole, L. (1996). Using a choice assessment to predict reinforcer effectiveness. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringdahl, J. E., Falcomata, T. S., Christensen, T. J., Bass-Ringdahl, S. M., Lentz, A., Dutt, A., & Schuh-Claus, J. (2009). Evaluation of a pre-treatment assessment to select mand topographies for functional communication training. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(2), 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, T. P., Kelley, K., & Higbee, T. S. (2016). Effects of simultaneous script training on use of varied mand frames by preschoolers with autism. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 32(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillingsburg, M. A., Frampton, S. E., Schenk, Y. A., Bartlett, B. L., Thompson, T. M., & Hansen, B. (2020). Evaluation of a treatment package to increase mean length of utterances for children with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(3), 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillingsburg, M. A., Powell, N. M., & Bowen, C. N. (2013). Teaching children with autism spectrum disorders to mand for the removal of stimuli that prevent access to preferred items. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 29(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior (pp. xi, 478). Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, M. L. (2014). The verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: A language and social skills assessment program for children with autism or other developmental disabilities (2nd ed.). AVB Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, M. L., & Michael, J. (2001). The benefits of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 698–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, M. L., & Partington, J. W. (1998). Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. AVB Press. Available online: https://avbpress.com/shop/teaching-language-to-children-with-autism-or-other-developmental-disabilities/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Tiger, J. H., Hanley, G. P., & Bruzek, J. (2008). Functional communication training: A review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1(1), 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsami, L., Lerman, D., & Toper-Korkmaz, O. (2019). Effectiveness and acceptability of parent training via telehealth among families around the world. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(4), 1113–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. T. (2019). Expressive Vocabulary Test—Third edition (EVT-3) [Measurement instrument]. NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, I. L., Steiner, V. G., & Pond, R. E. (2011). Preschool Language Scale—Fifth edition (PLS-5) [Measurement instrument]. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

| PsycInfo Search Strategy | ERIC Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| (“functional communication training” OR “functional communication response” OR “functional equivalence training” OR “mand” OR “mand training” OR “mand model” OR “teaching mands” OR “picture exchange communication system” OR pecs OR fct OR (funct* N/5 communic*) OR (pictur* N/5 communic*)) AND (“applied behavior analysis” OR “verbal behavior” OR “behavior analysis” OR “behavior analyst” OR “behavior modification” OR “behaviorism” OR “behaviorist” OR ((behav*) N/5 (therap* OR instruct* OR educ* OR profess* OR manpower)) OR (DE “Behavior Therapy” OR DE “Behavioral Health Services” OR DE “Therapists”)) AND (JN “Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis” OR JN “Behavior Analysis in Practice” OR JN “The Analysis of Verbal Behavior” OR JN “Behavior Modification” OR JN “Behavioral Interventions” OR JN “Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice”) | (“functional communication training” OR “functional communication response” OR “functional equivalence training” OR mand OR “mand training” OR “mand model” OR “teaching mands” OR “picture exchange communication system” OR pecs OR fct OR (“functional communication”) OR (“picture communication”)) AND (“applied behavior analysis” OR “verbal behavior” OR “behavior analysis” OR “behavior analyst” OR “behavior modification” OR “behaviorism” OR “behaviorist” OR (behavior* AND (therapy OR instruction OR education OR professional OR workforce))) AND (SO “Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis” OR SO “Behavior Analysis in Practice” OR SO “The Analysis of Verbal Behavior” OR SO “Behavior Modification” OR SO “Behavioral Interventions” OR SO “Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice”) |

| FCT | Mand | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Birth-3 years | 28 (11.2%) | 10 (9.6%) |

| 4–6 years | 100 (40.0%) | 51 (49.0%) |

| 7–12 years | 99 (39.6%) | 22 (21.1%) |

| 12–18 years | 17 (6.8%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| 19–64 years | 6 (2.4%) | 10 (9.6%) |

| 65 years + | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Autism | 190 (76.0%) | 82 (78.8%) |

| Developmental disability | 56 (22.4%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| ADHD | 30 (12.0%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| No diagnosis | 8 (3.2%) | 4 (3.8%) |

| Other | 78 (31.2%) | 12 (11.5%) |

| Not reported/unknown | 12 (4.8%) | 4 (3.8%) |

| Setting | ||

| Clinic (outpatient) | 189 (75.9%) | 45 (39.8%) |

| Clinic (inpatient) | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| School | 9 (3.6%) | 39 (34.5%) |

| Home | 44 (17.7%) | 21 (18.6%) |

| Vocational program | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not reported/unknown | 5 (2.0%) | 6 (5.3%) |

| Language Assessment | ||

| Descriptive Information | 152 (60.8%) | 47 (45.2%) |

| Information from IEP | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| PPVT a | 2 (0.8%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| VB-MAPP b | 4 (1.6%) | 25 (24.0%) |

| EESA c | 2 (0.8%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| VB-MAPP (Intraverbal Subtest) | 0 (0%) | 7 (6.7%) |

| ABLLS d or ABLLS-R e | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.9%) |

| EOWPVT f | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| EVT g | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| PLS h | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not Reported | 82 (32.8%) | 17 (16.3%) |

| Frequency | |

|---|---|

| FBA Components | |

| Indirect Assessment | 133 (53.2%) |

| Direct Assessment | 47 (18.8%) |

| Experimental Analysis | 243 (97.2%) |

| Topographies Targeted in Intervention | |

| Aggression | 192 (76.8%) |

| Self-Injurious Behavior | 92 (36.8%) |

| Disruptions/Property Destruction | 137 (54.8%) |

| Negative Vocalizations | 57 (22.8%) |

| Tantrums | 29 (11.6%) |

| Inappropriate Mealtime Behavior | 3 (1.2%) |

| Elopement | 9 (3.6%) |

| Surrogate of Behavior (e.g., Translational Research) | 13 (5.2%) |

| Stereotypic Behavior | 0 (0%) |

| Function Targeted in Intervention | |

| Tangible | 97 (38.8%) |

| Attention | 25 (10.0%) |

| Escape | 86 (34.4%) |

| Automatic | 2 (0.8%) |

| Synthesized | 87 (19.2%) |

| Social Control | 22 (8.8%) |

| Access to Rituals | 8 (3.2%) |

| Not Specified | 22 (8.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dawson, K.W.; Zangrillo, A.N.; Bryan, S.J.; Barall, R.J.; Wehr, C.G. Establishing Functional Communication Responses and Mands: A Scoping Review of Teaching Procedures and Implications for Future Investigation. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020182

Dawson KW, Zangrillo AN, Bryan SJ, Barall RJ, Wehr CG. Establishing Functional Communication Responses and Mands: A Scoping Review of Teaching Procedures and Implications for Future Investigation. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(2):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020182

Chicago/Turabian StyleDawson, Kyle W., Amanda N. Zangrillo, Samantha J. Bryan, Rebecca J. Barall, and Colin G. Wehr. 2026. "Establishing Functional Communication Responses and Mands: A Scoping Review of Teaching Procedures and Implications for Future Investigation" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 2: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020182

APA StyleDawson, K. W., Zangrillo, A. N., Bryan, S. J., Barall, R. J., & Wehr, C. G. (2026). Establishing Functional Communication Responses and Mands: A Scoping Review of Teaching Procedures and Implications for Future Investigation. Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16020182